3. From khanate to imperium: the First Bulgarian empire

The coming of Asparukh - Khan Tervel and Justinian II - The Treaty with Byzantium - An age of anarchy - Telerig the double-crosser - Khan Kardam and Empress Irene - Krum the conqueror - Omurtag the builder - Early Christianity: Knyaz Boris-Michael - Symeon the strong - Decline under tsar Peter - The Russians in Bulgaria - Tsar Samuel and the twilight of empire

4. The rise and fall of the Second Bulgarian empire

Under Byzantine rule - Delyan’s rebellion - Disorders in the Balkans - Arrival of the Crusaders - Bulgaria regains independence - Tsar Kaloyan the brave - Boril the inept - Achievements of tsar Ivan Assen II - Finance and trade - Decline of the central power - King Ivailo the swineherd - The rise of Serbia - George Terter and his successors - The Shishman dynasty - Ivan Alexander, patron of the arts - Decline and decay - The end of the Bulgarian empire

CHAPTER III. From Khanate to Imperium : The First Bulgarian Empire

The well organized and massive immigrations of Khan Asparukh and his Bulgar followers from north to south of the Danube between the years 679 and 681 serve as a watershed in Bulgarian history. These dates have an importance comparable to that of the Norman invasion of 1066 in the history of the British Isles. A large and prosperous part of the Byzantine homeland, after being ravaged by the Slavs, was now systematically overrun and colonized by an alien race from the steppes, the proto-Bulgars. These proceeded to set up a military and political organization which was to challenge the supremacy, if not the very existence, of Constantinople itself.

The appearance of the proto-Bulgars under Asparukh at the mouth of the Danube was in itself no sudden or unexpected phenomenon. Asparukh himself was a scion of the illustrious house of Dulo, to which also belonged Attila the Hun. It is recorded by Shirakatsi that Asparukh and his followers were established on the Danube estuary at Pyuki (Pevka) from about AD 650. A quarter of a century later, the proto-Bulgars began to establish a bridgehead south of the estuary.

When the Byzantine government’s efficient intelligence service brought early word of this development to Constantinople. Emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus (668-85) reacted vigorously. He hastened to conclude peace with the Arab caliph’s invading Saracen forces, and rushed his armies to the Danube. In 680, a large squadron of Greek ships under the emperor’s personal command sailed up the Black Sea coast, then disembarked north of the Danube delta. Byzantine cavalry squadrons were brought in from Anatolia, and reached the Danube via Thrace, only to get bogged down in the swampy marshes of the delta. The Bulgars evaded pitched battle with the Greeks; Emperor Constant tine IV, stricken by illness, abandoned his forces and beat an ignominious retreat. The Byzantine army attempted to recross the Danube, but was routed by the Bulgars, who advanced as far as Varna.

42

![]()

A peace treaty was then signed, recognizing Khan Asparukh’s annexation of the former Roman province of Moesia, and providing for the Byzantines to pay the Bulgars an annual tribute. The federation of the Seven Slav Tribes soon acknowledged the suzerainty of the Bulgars, and also paid tribute to Asparukh. The related Slav tribe of the Severi likewise rendered homage to Asparukh, though they were exempted from paying tribute.

(Plates 6-8)

Khan Asparukh is credited with the foundation of Pliska, the original capital of the First Bulgarian Empire, situated on an undulating plain not far from the modern town of Shumen.

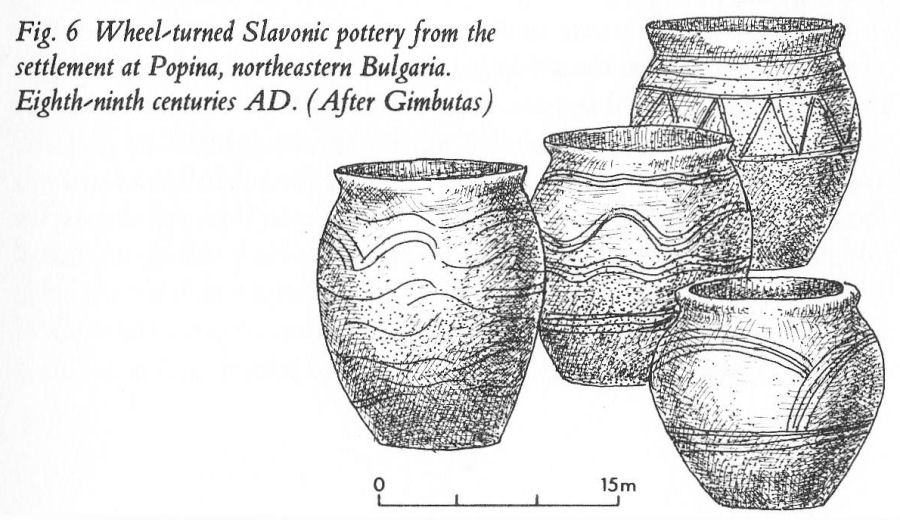

The exact numerical strength of the first Bulgar invasion horde is unknown, and may have been as little as fifty thousand. The role of these tough, well-disciplined steppe folk in galvanizing the scattered Slav agricultural communities into political and military activity was to prove crucial - comparable, in fact to the impact of Rurik and his Varangians on Kiev Rus’ some two centuries later. It is true that the settled Slavs were ahead of the nomadic Bulgars in agriculture, weaving, and some of the arts of peace. On the other hand, it may be argued that the proto-Bulgars were in many respects in advance of the Slavs in stock-breeding, pottery, sculpture, and even monumental architecture. Moreover, in literacy the Bulgars led the Slavs prior to the introduction of Christianity, and produced the remarkable corpus of proto-Bulgarian inscriptions - these were inscribed in Greek, though they contain over a score of proto-Bulgar terms, names, and titles.

(Fig. 6)

Fig. 6 Wheel-turned Slavonic pottery from the settlement at Popina, northeastern Bulgaria. Eighth-ninth centuries AD. (After Gimbutas)

Historically speaking, the vital point is that the proto-Bulgars introduced into the chaotic Slav world of the Balkans the notion of

43

![]()

an imperial destiny, backed by a rigid military and social hierarchy. This hierarchy was controlled by a warlike central bureaucracy, answerable to a single chief, the Sublime Khan. The autocratic power of the khan was, however, kept in check by ancestral custom, as well as by the jealous rivalry of the clan chiefs or bolyars, who were often powerful enough to band together and dethrone or slay any khan who proved incompetent or otherwise unacceptable to this élite body. In those days of the survival of the fittest, the aggressive instincts of the proto-Bulgars and their well tried military aptitude provided a catalyst without which the creation of a viable Slav state in the Balkans would have been long delayed, if not permanently frustrated.

The precise character of the social and economic relations between the Balkan Slavs and the proto-Bulgars is hard to establish with precision. Byzantine chroniclers continue during the eighth and ninth centuries to distinguish between the domains of the Bulgars, and those of the Slavs (Sclaviniae), though later all this territory came to be known as Bulgaria. Large tracts of land were seized forthwith by the proto-Bulgar aristocracy under Asparukh. Even so, the majority of the Slav peasantry was still free, and serfdom only took root gradually, particularly after the establishment of Christianity under Tsar Boris I.

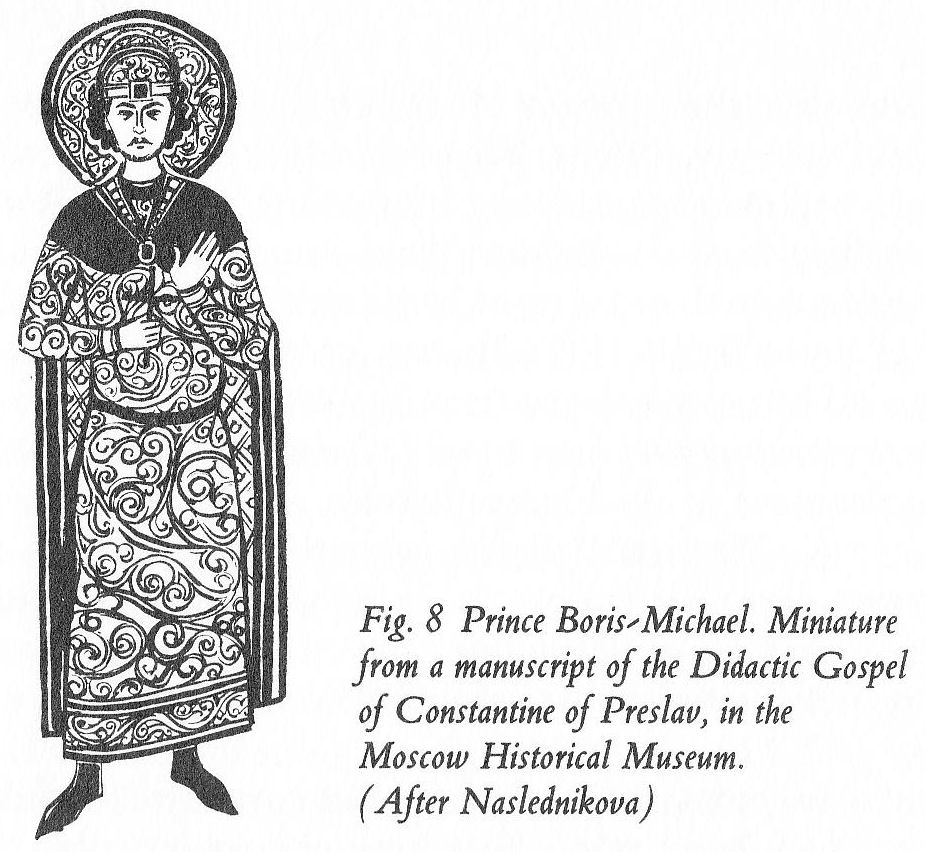

(Fig. 8)

Recent excavations at Devnya (Marcianopolis), in the hinterland of Varna, indicate that in the villages there was a mingling of Slavs and proto-Bulgar settlers at an early stage. Slav and Bulgar inhumations with grave-goods including pottery vessels of both Slav and Bulgar types are found side by side in village sites from the eighth century onwards. Whereas the Slavs normally burnt the corpses of their dead, the Bulgars had a preference for inhumation.

Interesting parallels may be drawn between the domestic architecture of the pagan Slavs in the Balkans, and that of the proto-Bulgars. The huts of the Slavs at this period were rather crude circular or square wattle and daub structures, often sunk into the ground to give the appearance of semi-dugouts. The Bulgars on the other hand favoured the portable leather tent or ‘yurt’. These tents were far more decorative and elaborate than is commonly imagined; a stone model of such a ‘yurt’ on show at the Varna Archaeological Museum is decorated with a graffito representation of a hunting scene, indicating that the walls of yurts were painted or adorned with embroidered panels.

44

![]()

(Khan Tervel and Justinian II)

On Asparukh’s death in 701, supreme power passed to Khan Tervel, son or grandson of Asparukh. Tervel continued the Bulgars’ expansionist policy in the Balkans, and added parts of eastern Thrace to the new Slavo-Bulgar state. Tervel was also in a position to intervene in the internal affairs of Byzantium, through his friendship with an exiled emperor, Justinian II, who sought refuge at the Bulgar headquarters in 705. This Justinian had had his nose cut off in a Constantinople palace revolution in 695, hence his nickname of ‘Rhinotmetus’, and then spent some years in exile at Cherson on the Black Sea, before marrying the daughter of the khaqan of the Khazars. Quarrelling with the khaqan, Justinian fled to Pliska, and persuaded Tervel to support him in a military campaign to regain the throne in Constantinople. Though unable to breach the capital’s mighty walls, Justinian adroitly crept into the city with a small band of daring followers. Emperor Tiberius II fled panic-stricken without a struggle, and Justinian regained his palace and the imperial throne.

Khan Tervel was enthroned by Justinian’s side, and granted the title of ‘Caesar’. The Bulgar state won renewal of the tribute payments inaugurated by Emperor Constantine IV. Thus the Bulgars had advanced in a quarter of a century, between 680 and 705, from the Danube estuary right up to the Bosporus and the heart of the imperial city, and found that they could even make and unmake Byzantine emperors. As a further recompense for his services, Tervel was allowed to annex the small but valuable district of Zagoria in northeastern Thrace, including the hinterland of the Gulf of Burgas.

Tervel proved himself an active and far-sighted ruler. When Emperor Justinian II turned against his former Bulgar allies in 708 and landed in Anchialus (Pomorie) with a large Greek force, Tervel launched a surprise attack which utterly routed the Byzantines. Three years later, Justinian himself was deposed and assassinated. In 712, Tervel invaded Thrace and advanced once more to the gates of Constantinople, retiring home laden with booty.

To the reign of Tervel is also ascribed the capture of the great port of Varna by the Bulgars. To prevent surprise attacks by the Greek fleet, the Bulgars built an immense earthwork along the southern portion of Varna Bay, some 3 kilometres long and 6 metres high. This earthwork incorporates many fine sculptured stones from the Roman and the

45

![]()

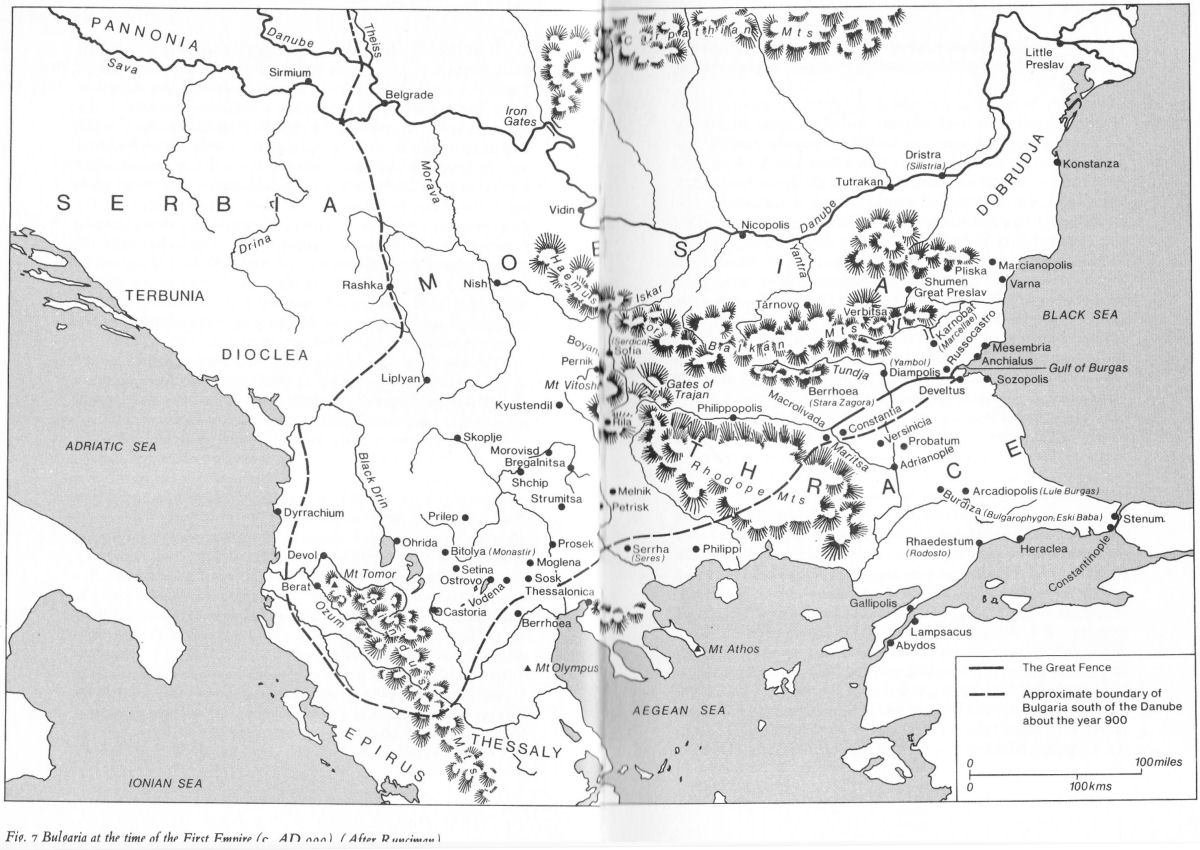

Fig. 7 Bulgaria at the time of the First Empire (c. AD 900). (After Runciman)

46-47

![]()

Byzantine period. It proved valuable in 773, when Emperor Constant tine Copronymus attempted a naval attack on Bulgaria with a large fleet, but was foiled.

Under pressure from the Arab caliphate, the feeble Emperor Theodosius III (715-17) sought to neutralize the Bulgar threat by concluding a political and commercial agreement with Khan Tervel, in 716. The terms of this treaty are summarized for us by the Byzantine historian Theophanes. The main political stipulations were that the state frontier should pass along a line later fortified by the Bulgars and known as the Great Fence of Thrace: the line extends from the Gulf of Burgas in the northeast, then through Bakajik, to a point on the river Maritsa about halfway between Philippopolis and Adrianople, reaching at one point the main Belgrade-Constantinople highway. The second article of the treaty provided for annual offerings to the Bulgar khan by the Byzantine court of costly robes and skins, to the value of thirty pounds of gold. The third clause related to return of prisoners by both sides, also mutual extradition of Bulgar or Greek refugees and political suspects, who might seek asylum with the opposing power.

(Fig. 7)

Of exceptional importance was the commercial agreement embodied in article 4 of the Treaty. There was to be free movement and interchange of officially licensed traders between Bulgaria and Byzantium, provided that such merchants were furnished with passports and seals, without which their goods might be confiscated. This convention enabled the Bulgarians to play an increasingly active part in exporting Thracian grain to the Byzantine cities on the Black Sea coast and elsewhere, and in the import of manufactured goods from Constantinople and the Mediterranean world through these ports into the interior of the Balkans.

Emperor Leo the Isaurian, who succeeded the ephemeral Theodosius, ratified the Bulgarian treaty. When the Arabs launched their second great siege of Constantinople, in 717, Khan Tervel aided the Greek defenders by swooping down on the Saracen encampment and slaying up to twenty thousand Arabs, before retiring home laden with booty.

Tervel died in the following year, but is immortalized in one of the three Madara inscriptions which flank the triumphant equestrian figure carved on a high cliff almost within view of the Bulgar capital of Pliska (see Chapter VII).

(Plates 4, 5)

This Greek inscription, carved in the rock-face,

48

![]()

mentions Tervel’s services to Emperor Justinian II, his acquisition of the Zagoria region, and his raid on the Saracens besieging Constantinople.

The remainder of the eighth century was a period of comparative stagnation in Bulgarian history, punctuated by wars against Byzantium, and bloody internal strife. Sources are scarce and one or two of the Sublime Khans are known only as shadowy entries in the medieval ‘Bulgarian Princes’ List’, found in Russia. We do not even know the name of Tervel’s successor, who reigned from 718 to 725. Then came Khan Sevar, who ruled until 740, and was the last of the great house of Dulo to occupy the throne; with him died out the lineage of Attila the Hun.

A new but short-lived dynasty sprang up with the accession of a bolyar named Kormisosh, of the house of Vokil or Ukil. He is mentioned briefly in the Madara inscriptions. Towards the end of Kormisosh’s reign, in 755, the warlike iconoclast emperor of Byzantium, Constantine V, called Copronymus (literally ‘Dung-named’), embarked on a forward policy in Thrace. He settled many Armenians and Syrians there, and built fortresses for them to inhabit and defend against the Bulgars. The latter protested; receiving no satisfaction, Kormisosh invaded Byzantine territory right up to the Long Wall of Constantinople. There Constantine Copronymus fell upon the Bulgars with his army and routed them utterly.

Kormisosh died in 756, and was succeeded by his son Vinekh, who had to bear the brunt of disastrous wars with Byzantium. The Bulgars lost patience with his record of defeats, and in 761 they rose up against their khan and massacred him with his family and all the other representatives of the house of Ukil.

In Vinekh’s place, the bolyars installed the thirty-year-old Telets, of the house of Ugain. Telets was the leader of the ‘war party’ in Bulgaria, and ordered a general mobilization, much to the disgust of his Slav subjects, of whom two hundred thousand deserted to seek refuge in Byzantium. In June 763, a great battle was fought near Anchialus (Pomorie); the carnage was immense, but in the end Constantine Copronymus was the victor. Triumphal games were held in the Constantinople circus, and thousands of Bulgar captives slaughtered. A few months later, Telets himself was assassinated, together with the bolyars of his party.

49

![]()

After several years of anarchy, the accession of Khan Telerig in 770 stemmed the tide of defeat. Despite a military reverse in 773, Telerig reorganized Bulgaria’s military forces, and also turned the tables on Emperor Constantine Copronymus by the exercise of cunning and guile. On one occasion, the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes tells us, Telerig sent a messenger to Constantine to report that opposition activity was rife, and might force him to take refuge in the Byzantine court. Telerig enquired who were the chief secret agents of Byzantium within Bulgaria, to whom he, Telerig, could have recourse in such an emergency. Constantine naively sent Telerig a list of Byzantine spies within Bulgaria, whom the khan promptly arrested and put to death. Ironically, Telerig did have to flee the country, in 777; he came to the court of Emperor Leo IV, accepted Christian baptism, and was accorded a Greek bride, a cousin of Empress Irene.

(Khan Kardam and Empress Irene)

During the reign of Irene and her son Constantine VI in Byzantium, from AD 780 onwards, the Empire had to contend with the capable Khan Kardam (777-802). At first, the Byzantines succeeded in pushing back the Bulgarian frontier to the north. In 784, Empress Irene made an imperial progress from Anchialus, far inland to Berrhoea, the modern Stara Zagora, which she rebuilt and christened Irenupolis. Serdica also remained firmly in Byzantine hands.

In 792, however, Kardam inflicted a disastrous defeat on the youthful Constantine VI at the border fortress of Marcellae. The Byzantine government had once more to submit to paying tribute to the Bulgarians, who periodically raised their demands with blackmailing threats of further military attacks. Constantine VI’s failure to check the Bulgarians helped to bring on the crisis of 797, in which Empress Irene had the Emperor, her son, blinded, and assumed autocratic power on her own.

Empress Irene fell from power in 802, and was succeeded by a former logothete of the Treasury (or Chancellor of the Exchequer), named Nicephorus. The following year, supreme authority in Bulgaria passed to one of the mightiest of Bulgaria’s early rulers, Khan Krum the Conqueror.

Krum is generally considered to have sprung from the lineage of the Bulgar khans of Pannonia, in Central Europe. His youth was occupied

50

![]()

so in establishing his power in Hungary and Transylvania, where he exploited the valuable salt mines. By about 808, Krum had joined these domains to the old Slavo-Bulgar khanate of Asparukh and his successors, and taken over as supreme master of Pliska. Krum was now sovereign of a realm which stretched from Thrace to the northern Carpathians, and from the lower Sava to the Dniester, and adjoined the Frankish empire of Charlemagne on the Tisza (Theiss). However, a mighty line of Byzantine fortresses, rebuilt by Constantine Copronymus, extended in a semicircle south of the Balkan range, barring the Bulgarian advance into central Thrace and Macedonia; its key points were Serdica, Philippopolis, Adrianople, and Develtus.

In 809, Krum suddenly appeared at the gates of Serdica. In spite of its impressive fortifications and strong garrison, he somehow gained an entry and massacred the defenders, six thousand strong, and numberless civilians. Several Greek officers, including a distinguished military engineer named Eumathius, deserted to the Bulgarian side. This triumph was outweighed, however, by disaster on Krum’s home front: Nicephorus had marched straight on Pliska, at the other end of Bulgaria, and found it virtually undefended. The Greeks plundered Krum’s palace and retired rejoicing to Constantinople.

This Byzantine triumph was short-lived. In May 811, Emperor Nicephorus set off with his son Stauracius on a great expedition designed to crush the Bulgar menace once for all. On the frontier, at Marcellae, Nicephorus met a delegation of Bulgarian envoys sent by Krum to sue for peace. Dismissing these envoys with contempt, Nicephorus pressed on to Krum’s capital of Pliska, which he devastated for a second time.

(Plates 6-8)

He amused himself by passing Bulgarian babies through threshing machines, and committed other atrocities. In July, Nicephorus rashly pursued the Bulgarian army into a rugged part of the Balkan mountains, and marched into a narrow, steep defile. The Bulgars built wooden palisades at either end of the pass, then fell upon the trapped Byzantines and massacred them wholesale. Emperor Nicephorus perished in the fray. This was a terrible blow to imperial prestige: not since the death of Valens at Adrianople in 378 had an emperor fallen in battle against the barbarians.

The head of Nicephorus was exhibited on a stake for some days in front of the jeering Bulgars. Then Krum had it lined with silver and

51

![]()

used it as a drinking cup from which to make wassail with his bolyars, to the refrain of the Slavonic toast of ‘Zdravitsa’, or ‘Good health!’

Stauracius, son and heir to the Byzantine throne, had been mortally wounded in the fray, and it now passed to Michael I Rhangabe. Meanwhile Krum seized Develtus, at the head of the Gulf of Burgas, and deported its inhabitants, including their Christian bishop, into the interior of Bulgaria.

A year later, in 812, Krum sent to Constantinople an ambassador named Dargomer (the first Slav name to feature in the official annals of Bulgaria) to renew the treaty of 716 between Khan Tervel and Emperor Theodosius III. Krum insisted on the extradition of Bulgarian deserters and refugees from Greek territory. On Michael’s refusal to hand them over, Krum assaulted the great Black Sea port and emporium of Mesembria (Nessebăr), situated on an almost impregnable peninsula north of Burgas. The Byzantine navy failed to relieve the town, which fell to Krum, along with vast quantities of gold and silver, and stocks of the Byzantine secret weapon known as ‘Greek fire’, complete with thirty-six syphons from which to project it.

(Plates 30-32)

In the year following, 813, Emperor Michael I sallied forth to meet Krum in pitched battle, but suffered a crushing defeat at Versinicia. This led to Michael being deposed, and succeeded by the wily Leo the Armenian (813-20). Krum advanced on Constantinople with an immense horde of Slavs and Bulgars, and demanded to be allowed to fix his lance to the Golden Gate, as a token of his supremacy. Leo prepared an ambush for Krum, but the Bulgar khan escaped the assassin’s darts, and vowed revenge on the Greeks. As a result, all the suburbs of the city, including the rich towns and villages on the far side of the Golden Horn, and up the European shore of the Bosporus, with their countless churches and monasteries and sumptuous villas, were sent up in flames. The emperor’s own palace of St Mamas was looted and burnt, and its ornamented capitals and sculptured animal figures packed up and loaded into wagons to adorn the Bulgar capital of Pliska (see Chapter VII). On his way home, Krum captured Adrianople, and deported most of the surviving inhabitants into Bulgarian domains north of the Danube. Among these captives was an Armenian family with a little boy who by an odd twist of fate was later to become the Byzantine emperor Basil I.

52

![]()

Krum now began to plan the coup de grace against the demoralized Byzantines. Avar auxiliaries poured into Bulgaria from Pannonia, and Slavs assembled from the Sclaviniae. Vast siege engines were constructed, also immense catapults, tortoises, battering-rams and ladders. In despair, the Greeks sent envoys to plead for help from the Western Emperor, Louis, in the hope of organizing a ‘second front’ from the direction of Germany. But on Holy Thursday, 13 April 814, what seemed like a miracle occurred: Krum burst a blood vessel, and the ‘new Sennacherib’ died a sudden death.

Such was the terror instilled by Krum and his mighty hordes that this aspect has distracted us from his administrative and legislative achievements. Yet we have reason to believe that Krum was a systematic and clever administrator, as is evidenced, for instance, by the Hambarli inscription (now in the Varna Archaeological Museum), which takes the form of a rectangular stone pillar carved with a detailed battle order of the Bulgarian army, inscribed in Greek, but complete with a number of proto-Bulgar official and military titles. The Byzantine encyclopaedia known under the name of Suidas (tenth century) credits Krum with a comprehensive legislative programme, including measures against perjurers and thieves. Preoccupation with social welfare is evident in Krum’s injunction that the poor and needy were to be supported by the rich, under pain of confiscation of property. Hearing that the Avar realm had fallen partly as a result of drunkenness among the population, Krum is said to have ordered the rooting up of all vines in Bulgaria - though how this can be reconciled with his taste for drinking wine out of a human skull is hard to explain.

When Omurtag succeeded his father Krum, he was young and inexperienced, and a group of bolyars for a time disputed the succession the to the throne of Pliska. By the end of 815, however, Omurtag was firmly builder established in power. He was to prove one of the most enlightened of Bulgaria’s pagan rulers in spite of his cruel persecution of the Christians, dictated largely by political considerations; he was a great builder and patron of the arts.

Omurtag’s first political act was to conclude a thirty years’ peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire, whereby he gave up the territory in southern Thrace briefly occupied by Krum, and reverted in the main to

53

![]()

the line established earlier by Khan Tervel. The Bulgarians then dug a great ditch and rampart from Develtus (near Burgas on the Black Sea), inland to Macrolivada, and manned it with a string of guard posts.

(Plates 6-8)

Omurtag used the respite given by the peace treaty to complete a vast programme of monumental building and public works. He raised for Plates 6-8 himself a great palace at Pliska, to replace that of his father Krum, burnt down by Emperor Nicephorus. At Transmarisca on the Danube, he built a castle to guard the northern approach to Pliska; to the southwest, he founded in 821 the beautifully situated town and future capital of Great Preslav. In the open countryside not far from Shumen, Omurtag erected the cavalry barracks known as the Aul of Omurtag, consisting of a square walled stockade built of brick, complete with stables for horses, and living quarters inside for picked cavalrymen. A scale model of the Aul may now be seen in the Shumen museum. Halfway between Pliska and the Danube, Omurtag had a mausoleum built for himself.

Peace with Byzantium also enabled the Bulgarians to turn their attention to Western Europe, where they were troubled by the advance of Louis the German, king of the East Franks. In 827 and again in 829, Omurtag invaded Pannonia, and imposed his own governors on the local Slav tribes. Peace in this quarter was not concluded until after Omurtag’s death.

Omurtag’s reign was a time of ideological and religious crisis and strife. The pagan priests or shamans of the proto-Bulgars, and the heathen priests of Perun, patron deity of the Slavs, joined in suppressing the numerous adepts of Christianity dwelling within Bulgarian territory (many of them former prisoners of war), and also in combatting the influence of the Greek and Frankish Christians from just over the border. Omurtag himself was aware, it would seem, of the prestige which Christianity afforded the Byzantine Emperor and the successors of Charlemagne, as vice-regents of God upon earth. He adopted the title of ‘ Arkhon, or sovereign, by the grace of Cod’, even though the supreme pagan god, not the God of the Christians, was meant. Yet reasons of state demanded massive persecutions of the Christians. Among those who died a martyr’s death were four bishops, including Archbishop Manuel of Adrianople, and 377 other captives. Their memory was celebrated annually in Constantinople on January 22, and their martyrdom described in the Greek Synaxarium.

(Fig. 25)

54

![]()

The most determined enemies of Christianity, apart from the priests themselves, were the Bulgar bolyars or noblemen. The Slavonic population was more responsive to Christian propaganda, much of it emanating from descendants of the original Byzantine Christians, whose forbears had survived the waves of invasion in the Balkans. A certain amount of intermingling of the Slavonic peasant and chieftain classes with these old local elements was certainly taking place by this period.

Of particular interest is a short choral Office in honour of the Bulgarian martyrs, discovered in the Vatican Library, and published by Enrica Follieri in 1963. The hymnographer, evidently a contemporary of these tragic events, was called Joseph, and is probably to be identified with Joseph of Studios, a noted Byzantine author. The hymn indicates clearly the varied ethnic and social background of the Bulgarian martyrs of this period.

In spite of his occasional cruelties, Omurtag remains one of the most fascinating of all Bulgar rulers. None but a philosopher, albeit a pagan one, could have dictated the words found on a granite column now embodied in the Church of the Forty Martyrs at Great Tărnovo:

Man dies, even though he lives nobly, and another is born; and let the latest born, seeing this, remember him who made it. The name of the prince is Omurtag, the Sublime Khan. God grant that he live a hundred years.

However, Omurtag was not fated to live for a century: he died comparatively young in 831, after reigning for sixteen years.

(Early Christianity: Knyaz Boris-Michael)

Under Omurtag’s successors Malamir (831-36) and Pressian (836-52) the Bulgarians penetrated further into Macedonia, and annexed large areas of what is now southern Yugoslavia. The internal crisis resulting from the spread of Christianity, and the exacerbated reaction of the pagan priests, continued at boiling point, and even led to the execution of Prince Enravotas, a brother of Khan Malamir, who was converted to Christianity by a Greek captive from Adrianople.

(Fig. 8)

A new era in Bulgarian history was inaugurated in 852, with the accession of Khan Boris, who later assumed the name of Michael on his conversion to the Christian faith. The early part of Boris’s reign was

55

![]()

Fig. 8 Prince Boris-Michael. Miniature from a manuscript of the Didactic Gospel of Constantine of Preslav, in the Moscow Historical Museum. (After Naslednikova)

occupied with unsuccessful campaigns against the Frankish empire and its Eastern satellites, notably the Croats. Later Boris attempted, unsuccessfully, to annex areas of Serbia and what is now Albania.

As the years went by, Boris became aware of the spiritual bankruptcy of traditional Bulgarian paganism, which had become more and more associated with social backwardness, illiteracy and also with potential feudal resistance to the royal power. Paganism, by the mid-ninth century, appeared clearly inferior both spiritually and politically to Orthodox and Catholic Christianity alike, as well as to the splendid edifice of Islam under the Arab caliphs, the triumphant Commanders of the Faithful. Not only did Christianity offer cultural and social progress through the introduction of literacy and a disciplined way of life, but it provided a framework for the aggrandisement of the monarchy: in Byzantine Christianity, especially, the sovereign was conceived of as a divinely anointed autocrat and a lay pontiff with supreme authority not only over State and People, but over the Holy Church itself. For a country to remain pagan, on the other hand, was to opt for political weakness and social barbarism.

Leaving aside reasons of state, there is no need to question Boris’s religious conviction, when the moment came to make his decision. Boris

56

![]()

had witnessed and heard of the heroism of the Christian martyrs put to death during preceding reigns - heroism which won international renown, and brought disgrace and shame upon the cruel, heathen Bulgarians in the eyes of the world. Boris had certainly heard much of the sublimity of the Orthodox liturgy, as celebrated in Saint Sophia cathedral in Constantinople and other shrines well known to Bulgarian merchants and travellers. There is a story told in the Russian Primary Chronicle concerning the conversion of the Russians in the tenth century.

Prince Vladimir sends envoys to various peoples in search of the true faith. The Russian envoys report unfavourably on the Volga Bulgars and the Germans, but add:

Then we went to the Greeks [to Constantinople], and they led us to the place where they worship their God; and we knew not whether we were in heaven, or on earth. For on earth there is no such vision nor beauty, and we do not know how to describe it; we know only that there God dwells among men.

How different were these splendours of St Sophia from the crude mouthings of Bulgaria’s pagan shamans!

While Boris was pondering these matters, a violent religious and political conflict had set the Papacy and the Constantinople patriarchate at loggerheads. It was the ambition of Pope Nicholas I (858-67) to reassert the supremacy of Rome over the entire Church Universal. His refusal to recognize the legitimate succession of the Constantinople patriarch Photius culminated in 863 in formal excommunication of the latter, in response to which Photius made the audacious gesture of excommunicating Nicholas.

Just at this time, Prince Rastislav of Moravia sent envoys to Emperor Michael III in Constantinople, in search of a military and political alliance. To head the return mission to Moravia, the emperor’s choice fell on two eminent brothers from Thessalonica, Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius, to whom the Slavonic peoples are indebted for their conversion to Christianity, and for the invention of the earliest Slavonic alphabets, the Cyrillic and the Glagolitic.

Boris of Bulgaria was still toying with the idea of officially embracing Christianity. One account ascribes his final conversion to a Greek

57

![]()

slave called Theodore Cupharas, who taught Boris to pray to the God of the Christians and thus avert a terrible famine which threatened Bulgaria with starvation. Another version of the events gives the credit to a Christian painter named Methodius (not to be confused with the missionary from Thessalonica), who terrified Boris by a realistic mural painting of the Last Judgement.

It fell to Boris to make a choice between Rome and Byzantium, the two founts of Christian dogma and discipline. Early in the 86os, Boris evidently undertook to receive Christianity at the hands of the Frankish Catholic clergy. This decision had clear-cut political implications. The danger of Carolingian influence spreading right into Thrace, within easy reach of Constantinople, seriously alarmed the Byzantines. Emperor Michael III determined on a military demonstration, moving an army to the Bulgarian frontier, and sending a fleet along Bulgaria’s Black Sea littoral. The Greeks demanded the abandonment of the Frankish alliance, and the conversion of the khan of Bulgaria to the Orthodox persuasion.

The Bulgarian military position was precarious, and the country suffering from famine, so Boris capitulated at once. In 864 (or, according to some authorities, in 865), the Bulgarian khan received baptism at the hands of priests sent from Constantinople, taking the name of Michael after that of the Byzantine emperor who stood as his sponsor and godfather. Boris abandoned the pagan Turkic title of khan for the Slavonic ‘knyaz’ or chief prince. Mass conversion of the people, often by force, followed. A pagan insurrection headed by many leading Bulgar bolyars was crushed with severity, no less than fifty-two ringleaders being executed together with their families.

This first honeymoon between the Byzantine and Bulgarian Churches ended in bitterness and rupture. Antagonized by Greek arrogance, Boris-Michael decided to renew his former links with the West. In the summer of 866, he sent envoys both to the court of Louis the German at Ratisbon, and to Pope Nicholas I in Rome. To the Pope he forwarded a set of 106 questions on theological, social, also legal and political matters, together with a plea for an independent patriarch for the Bulgarian Church.

Boris-Michael’s questionnaire to the Pope reflects the usual mixture of bewilderment and occasional resentment, combined with an honest desire to please, which marks the response of simple pagans the world

58

![]()

over, when exposed to the threats and blandishments of well-meaning Christian missionaries. For all their occasional naivety, Boris-Michael’s questions to Pope Nicholas, taken together with the Pontiff’s answers, provide one of the most interesting documents we possess on social conditions in the First Bulgarian Empire. Were the Byzantines correct, asked Boris-Michael, in imposing fasts on Wednesdays as well as on Fridays, and in banning baths on both days? (This love of bathing among the Bulgars is also demonstrated by the elaborate hypocausts which existed at the residence of Khans Krum and Omurtag at Pliska.)

(Plate 8)

Should they wear their belts while taking communion, and remove their turbans in church? Must they abandon their fashion of wearing trousers? How were they to dispose of their surplus wives, in view of the widespread custom of polygamy among the pagan Bulgars; Was sexual intercourse permitted on Sundays or not? Were laymen allowed to conduct public prayers for rain, or only priests, and could ordinary people make the sign of the Cross over the table before a meal? How many true patriarchs were there, and was it true that Constantinople ranked in the hierarchy immediately after Rome?

The Pope’s exhaustive replies to these and many other questions are most interesting. Nicholas chided Boris-Michael for the severity of his punishment of civil offenders, and urged him to abandon the use of torture in criminal proceedings. Forced conversion to Christianity should be replaced by persuasion. The Pope condemned various pagan practices described in Boris-Michael’s questionnaire, such as the use of a horse’s tail as a banner for the army, the seeking of auguries, the casting of spells, and the performance of ceremonial songs and dances before battle, as well as the taking of oaths on a sword. The Bulgarians were also urged to give up their superstitious practice of seeking cures from a miraculous stone, and wearing amulets round their necks as a protection against sickness. As for the status of the patriarchal see of Constantinople, Nicholas dismissed its apostolic pretensions contemptuously, and was scathing in regard to its claim for monopoly of production of the Holy Chrism. On the setting-up of an independent Bulgarian Church, Nicholas was prudently evasive, indicating that everything depended on the Christian prowess of the newly converted Bulgarian nation.

A rapid sequence of events now led up to a definitive swing by the fickle Bulgarians back towards the fold of Byzantine Orthodoxy. Pope

59

![]()

Nicholas firmly refused to ratify Boris-Michael's choice of a Roman Catholic primate for the infant Bulgarian Church, insisting that the appointment of bishops for Bulgaria was an exclusive papal prerogative. By the summer of 867, prior to the death of Pope Nicholas and the accession of Hadrian II, Bulgarian relations with Rome became strained.

Meanwhile, in Constantinople, a palace revolution took place in September 867, in the course of which Emperor Michael III was murdered by his favourite protégé, the future Basil I, himself an Armenian who had spent part of his childhood as a captive in Bulgaria. Basil deposed Patriarch Photius and reinstated his rival Ignatius. Since Ignatius was persona grata with the Papacy, his appointment restored communion between Constantinople and Rome. A council of the Oecumenical Church, attended by representatives of Pope Hadrian II, was held in Constantinople during 869 and 870, and decided that Bulgaria should depend on the Greek patriarchate of Constantinople, and thus Bulgaria duly receive her semi-autonomous archbishop and subordinate clerics from the metropolitan see of Byzantine Christendom.

The next landmark in the history of Bulgarian Christianity occurred in 885, when Methodius died in Moravia, his whole work apparently on the brink of failure. Methodius had towards the end of his life fallen out with the Papacy, partly as a result of his refusal to tolerate any tampering with the Nicene Creed. The death of Methodius meant the end of the Slavonic liturgy in Central Europe. He had named his ablest disciple Gorazd as his successor, but Gorazd was unable to maintain his position in face of relentless opposition from the Latin and German clergy, egged on by the Moravian Prince Svatopluk I. The leaders of the Slavonic Church in Moravia - Gorazd, Clement, Nahum, Angelarius, Laurentius and Sabbas - were imprisoned; some of them were then deported, and on reaching Belgrade, were warmly welcomed by Boris-Michael’s viceroy there, who sent them on to Pliska. Other survivors of the Slavonic Moravian Church reached the Bulgarian capital via Venice, where they had been sold as slaves, and redeemed by Byzantine envoys acting on behalf of Emperor Basil I.

About 886, Clement was sent from Pliska to Macedonia, with instructions to baptize any who were still pagans, to celebrate the liturgy in the Slavonic tongue, translate Greek religious texts, and train a native

60

![]()

clergy. The centre of his activity was the district of Devol (in present' day Albania), between Lake Ohrida and the Adriatic; after consecration as bishop in 893, Clement concentrated on the Ohrida area itself. Thanks to Clement’s exemplary labours over a period of thirty years, Macedonia (above all Ohrida) became a leading centre of Slavonic Christian culture, and a hearth of early Bulgarian civilization.

At first, Clement’s comrade Nahum remained in northeastern Bulgaria, where, both in Pliska and at the royal monastery of St Panteleimon (Patleina) close to Preslav, he helped to found another school of Old Bulgarian literature, until transferred to Macedonia in 893 to assist Clement in his educational and missionary labours. The importance of Clement, Nahum and their associates in laying the foundations of Old Bulgarian literature and Christian culture is examined in more detail in Chapter VI.

In 889 after a reign of thirty-seven years - one of the longest in Bulgaria’s annals - Boris abdicated and retired to a monastery, possibly that of St Panteleimon at Preslav. The throne passed to Vladimir, eldest son of Boris, who immediately abandoned most of his father’s policies in favour of a return to paganism, in which he was encouraged by the reactionary Bulgar bolyars. Court life became extravagant and debauched, and the Byzantine alliance was abandoned for a pact with the German emperor Arnulf.

The reign of this Bulgarian equivalent of Julian the Apostate lasted four years, until 893, when Boris was finally provoked to the point of rallying the faithful against his own son. After having Vladimir blinded and imprisoned, Boris summoned a general assembly of the nation, which proclaimed Boris’s younger son, the monk Symeon, as ruler, annulling Symeon’s monastic vows. From now on, Slavonic replaced Greek as official language of the Bulgarian State, and the capital of the country was moved from Pliska, with its pagan associations, to Preslav, which Boris had already beautified with churches and monasteries, workshops and scriptoria.

(Plates 18-21, Figs. 30-33)

Under the reign of Tsar Symeon, which lasted more than thirty years, the might of the First Bulgarian Empire reached a new peak, equalling the epic age of Khan Krum. Symeon had originally been trained for the post of archbishop of Bulgaria. Raised in Constantinople,

61

![]()

as a royal hostage, he followed courses at the University installed in the Magnaura palace. He became a proficient Greek scholar, with a taste for the works of Aristotle and Demosthenes; later he came to favour the Fathers of the Christian Church.

On emerging from his cell to take over the Bulgarian throne from his blinded brother, Vladimir, Symeon soon adapted himself to the outside world, and the requirements of statecraft and war. Towards the end of his life, indeed, he developed a streak of militaristic megalomania. Like Krum before him, Symeon dreamed of founding a new Slavo-Byzantine empire centred on Constantinople, the head of which would be himself, a Bulgarian, arrayed in the imperial purple of the Greeks.

Meanwhile, Symeon set out to transform Preslav into a second Constantinople. According to a contemporary writer, John the Exarch, visitors to Preslav were overcome by the sight of all the great Plates 18-21, churches and palaces, decorated with marbles and frescoes, and depicting the sights of heaven, the stars, sun and moon as well as flowers and trees and the fishes of the deep.

(Figs. 30-33)

In the midst of all this splendour sat Symeon himself, enthroned ‘in a garment studded with pearls, a chain of medals round his neck and bracelets on his wrists, girt with a purple belt, and having a golden sword by his side’. John the Exarch adds that any rustic Bulgarian tourist who glimpsed these sights would return home, disenchanted with the simplicity of his own humble cottage, but eager to tell his friends about the wonders of Symeon’s new city.

War with Byzantium broke out in 894, the year after Symeon’s accession. The immediate casus belli was a commercial dispute. Since Khan Tervel’s commercial treaty of 716, there had existed a regular Bulgarian trade depot in Constantinople, protected by special imperial privileges. Under Tsars Boris and Symeon, the Bulgarians came to depend increasingly on export outlets for their local products - wines, beasts, corn, timber and many other commodities - and the chief outlet was Constantinople. In exchange, the Bulgarians imported Byzantine and oriental manufactured products, such as dyed silk, jewellery and porcelain, also spices. A crisis arose when the courtier Stylianus Zautses, Logothete of the Drome, encouraged two Greek merchants to establish a monopoly of Greek trade with Bulgaria, the depot for which they transferred from Constantinople to Thessalonica, where heavy taxes were imposed on Bulgarian goods.

62

![]()

Symeon demanded compensation for losses sustained. Rebuffed,

Symeon invaded Thrace and marched on Constantinople. Emperor Leo VI responded by sending envoys to the Magyars, who at this time were encamped north of the Danube estuary, in the plain of Bessarabia. The Magyars were ferried across the Danube by the Greek fleet, and advanced on Preslav, forcing Symeon to abandon his march on Constantinople and hurry northwards to defend his own capital. Symeon in his turn persuaded the dreaded Turkic Pechenegs to attack the Magyars from the direction of the Dnieper, forcing them to move westwards over the Carpathians into the Pannonian plain, where they founded the medieval kingdom of Hungary.

Peace was concluded in 897 on terms quite favourable to Bulgaria, including provision for an annual tribute of gifts to be rendered to Symeon by the Greeks. This treaty lasted for fifteen years, until Leo Vi’s death in 912. Then Leo’s brother, the short-lived alcoholic emperor Alexander, insulted Symeon’s envoys sent to renew the 897 treaty. War broke out, and lasted with intervals until Symeon’s death in 927. On one occasion, in 924, Symeon reached the walls of Constantinople and engaged in personal parley with Emperor Romanus Lecapenus.

An interesting source for the history of the period is the exchange of letters between Patriarch Nicholas of Constantinople and his erstwhile brother in Christ, the renegade monk Symeon, now prince of the hosts of Bulgaria. These letters, alternately threatening and cajoling, and Symeon’s disrespectful, bantering replies, illustrate the paradoxical character of this Christian ruler whom fate had turned into the bitterest foe of Byzantium - the fount of Bulgaria’s new Christian culture. At times, Symeon acted as a worthy candidate for the imperial crown of Byzantium; at others, he behaved like the veritable descendant of Attila the Hun, reverting to the uncouth ways of his ancestors.

Symeon was the creator of both the Bulgarian Empire, and the Bulgarian patriarchate. In 925, he proclaimed himself Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans and the Bulgars, a title ratified by the Pope, and revived later under the Second Bulgarian Empire. (By the Romans, are meant the Byzantine Greeks and their subject races.) In 926, Symeon proclaimed the independence of the Bulgarian Church within the Orthodox communion, under its own patriarch, the former Archbishop Leontius.

63

![]()

Out of the ordinary in so many respects, Symeon was remarkable even in the manner of his death. In May 927, a Greek astrologer told Emperor Romanus Lecapenus that the thread of Symeon’s life was bound up with the existence of a certain marble column in the Constantinople forum. On May 27, Romanus, as an experiment, had this column’s capital removed. At this same hour, Tsar Symeon died of heart failure. Apocryphal though it may be, this story gives some impression of the awe inspired by this larger than lifesize, controversial ruler.

It was under Symeon that the military and government machinery of the First Bulgarian Empire reached its greatest size and complexity. Although no comprehensive survey of this machinery exists, yet we can piece together from various sources and inscriptions a fair picture of the salient features of this state structure.

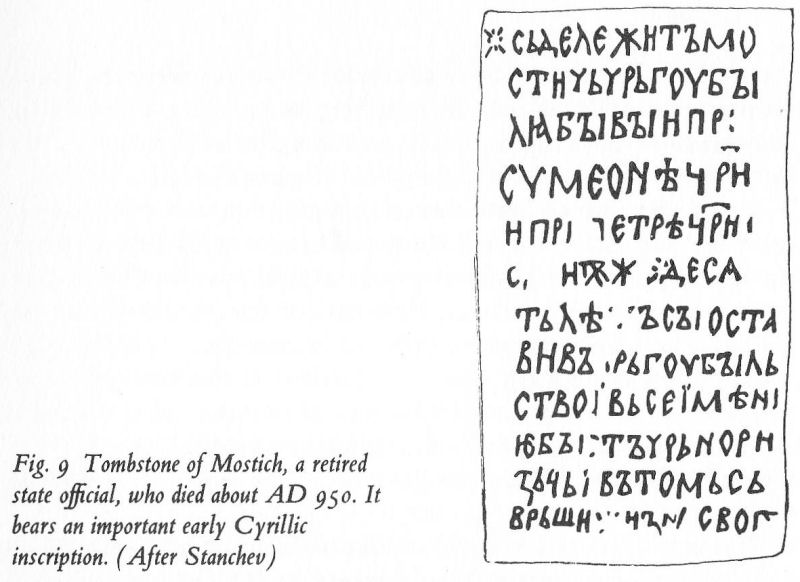

Slavonic and proto-Bulgar titles continued to exist side by side for over a century after Bulgaria’s conversion, while ecclesiastical ranks are largely taken from the Greek. To give a few examples, we find that under Boris-Michael the Sublime Khan becomes Knyaz or Prince, a Slavonic title used in Russia up to modem times; Symeon assumed the title of Tsar or Emperor. The Bulgar aristocracy of the boïlyas or bolyars had their name transformed into the Slavonic form boyar. Tribal chiefs bore the Slavonic title zhupan, a princely dignity even better known in medieval Serbia. Constantine Porphyrogenitus refers to a high military officer termed 'Alo-Bogotur’, embodying the Turkic bagatur (Russian, bogatyr), meaning a hero. From the end of the ninth century dates a handsome lead seal of a certain Bulgar Khan-Bagatur Irtkhituin; the seal, which is illustrated in Vasil Gyuzelev’s biography of Boris I, is adorned with a Christian cross. Around AD 950, we encounter the tombstone of a certain Mostich, with an important Slavonic inscription mentioning that he was chărgoboïlya (officer in charge of state security) under Tsars Symeon and Peter, and had retired at the age of eighty to become a monk.

(Fig. 9)

Sometimes high Bulgarian officials would be known to the Byzantines by Greek equivalents of their Bulgarian titles; thus the Bulgarian tarkhan of Belgrade is referred to in the Life of St Clement of Ohrida as hypostrategus or military governor-general of the province. Greek ranks and titles, for obvious reasons, predominated in the Bulgarian Church.

64

![]()

Fig. 9 Tombstone of Mostich, a retired state official, who died about AD 950. It bears an important early Cyrillic inscription. (After Stanchev)

Apart from such common terms as those of patriarch or bishop (‘episkop’), we find in Bulgaria the title of exarch, also that of syncellus. The latter was, in Byzantium, a high cleric, who often acceded later to the patriarchate; he was appointed by the emperor in agreement with the patriarch, and was instituted with much pomp at a ceremony in the imperial palace. The syncellus, in Byzantium at least, took precedence over all the ordinary officials and acted as a kind of liaison officer between the emperor and the patriarch.

It has to be noted, however, that in spite of the elaborate structure of State power under Symeon, the commercial and financial base remained primitive and weak. Although the later rulers of the First Bulgarian Empire made lead, silver and gold seals for ceremonial and business use, none of them attempted to strike coins in their own name. They remained slavishly dependent on the Byzantine currency and on barter. An independent coinage did not evolve in Bulgaria until after the establishment of the Second Bulgarian Empire at Tărnovo, at the very end of the twelfth century.

Symeon’s imperial title and grandiose conquests had been bought at too high a price. The country was exhausted. Symeon’s successor, Tsar Peter, was physically a weakling, under whom Bulgaria rapidly fell

65

![]()

into decline. The Byzantines wisely bided their time; they even established a form of alliance with Bulgaria by granting young Tsar Peter an imperial bride, the Princess Maria, granddaughter of Romanus Lecapenus, known in the annals of Bulgaria as Empress Irene.

Peter’s reign, which lasted from 927 to 969, was one of the longest but most disastrous in Bulgarian history. The country lay inert, a passive prey to savage invaders from the north. In 934, for instance, the Magyars made a deep incursion into the Balkans, and reached Develtus, near Burgas; so great was the number of their captives that a pretty woman could be bought for a silk dress. The humbler classes were restless; in 930, Peter’s brother Michael escaped from the monastic cell to which he had been relegated, and made off to the western mountains, where he founded a kind of brigand kingdom aided by large bands of Slav malcontents.

This general unrest also found expression in a most wide-spread and politically dangerous heresy, that of Bogomilism. This will be dealt with in more detail in Chapter V, and here it will suffice to observe that the Bogomils taught that matter was the creation of the devil, and that the service of principalities and powers was anathema to God, as was the whole structure and hierarchy of the Orthodox Church. As so often before and since (and we have only to think of the French Huguenots or Cromwell’s Puritan Roundheads), religious dissent gave rise to militant social action; and in the absence of anything like modern political parties, the pent-up resentment of the underprivileged found an outlet in Bogomilism as a new, exciting form of religious protest.

Towards the end of his life, in 965, Peter made a diplomatic blunder which was to plunge Bulgaria into fresh misery. He sent envoys to Constantinople to demand from the new, warlike Emperor Nicephorus Phocas (963-69) a resumption of the subsidy which the Byzantines had formerly paid to the Bulgarian Sublime Khans, and which the Greeks had renewed in the form of a dowry when Tsar Peter of Bulgaria married the Greek princess Maria-Irene in 927. But Maria-Irene had just died, and Nicephorus Phocas professed himself highly insulted at this Bulgarian demand for what was described as ‘the customary tribute’. Nicephorus and his courtier poured abuse on the Bulgarian ambassadors, terming them ‘filthy beggars’, and cursing their master, Tsar Peter, as being no emperor, but a princeling clad in skins.

66

![]()

Possibly this was but a form of diplomatic provocation, designed to prepare the way for unleashing upon the enfeebled Bulgarians the military might of the Russians and Varangians, who constituted a regular threat to Constantinople through their superior naval strength. Peter did his best to fend off the approaching menace, sending his two sons Boris and Romanus as hostages to Constantinople. But Nicephorus continued with his plans; he sent an envoy to the Russian court in Kiev, bearing a subsidy of 1,500 pounds of gold, as an inducement to the heathen Prince Svyatoslav to cross the Danube and invade Bulgaria from the north.

In August 967, Prince Svyatoslav crossed the Danube with the imperial the ambassador Calocyras as guide, and sixteen thousand men. Svyatoslav Russians in overran the north of Bulgaria, capturing twenty-four towns, and then Bulgaria set up a wartime capital at Khan Asparukh’s old fortress of Little Preslav on the Danube. Svyatoslav took such a fancy to this region that he seriously thought of moving his capital permanently from Kiev to Little Preslav, which he found a most attractive spot; it was also an important economic centre, receiving silver, fabrics, wines and fruits from Greece; silver and horses from Bohemia and Hungary; and skins, wax, honey and slaves from Russia itself.

Marching south, Svyatoslav captured Great Preslav in 969, proceeding thence to storm Philippopolis (Plovdiv), the metropolis of Thrace. Emperor Nicephorus realized that the situation had got thoroughly out of hand, and that the Russians would soon be appearing at the gates of Constantinople by land, as they had already several times appeared by ship. Another disquieting factor was the news that Patrician Calocyras, the imperial ambassador, had turned traitor, and was seeking to make a bid for the imperial throne of Constantinople.

Nicephorus was indeed in dire peril, but the blow when it fell on the night of 10 December 969 came from within his own household. Empress Theophano had taken as her lover the Armenian general John Tzimiskes, who was the moving spirit in a palace plot that put an end to Nicephorus’s life as well as to his warlike plans, which were to be worthily continued by Tzimiskes himself. It is interesting to note that Tzimiskes, who was to extinguish the First Empire in Eastern Bulgaria, was born in a small Armenian town called Khozan in Anatolia, which

67

![]()

later adopted the emperor’s name - Tshmishkatzak. He was a great' nephew of an outstanding Armenian general in the Byzantine service, the Grand Domestic John Curcuas.

John Tzimiskes immediately turned his attention to the situation in the Balkans, deputing the half-Armenian Bardas Sclerus to take charge of operations. In Bulgaria, Tsar Peter had died in 969, to be succeeded by his son Boris II, who had been sent back from Constantinople.

The Russian prince Svyatoslav failed to take the measure of Tzimiskes’s military genius, and sent insolent messages to Constantinople, affecting to order the Byzantines out of Europe altogether, unless an enormous tribute was paid. In the spring of 971, at the head of a large and well' trained army, Tzimiskes set out on one of the most brilliant campaigns in Byzantine history. In April he took Great Preslav from the Russians after a furious battle. Svyatoslav’s men then fell back to the Danube and fortified themselves in Silistra (Dristra, Dorystolum). After three months of siege the Russians and Varangians were worn out by the assaults of the Byzantine crack troops and harassment by fire-shooting ships of the imperial Byzantine navy on the Danube. Svyatoslav capitulated, and negotiated an armistice to allow himself and his followers to return unmolested to his capital of Kiev, pledging himself never again to attack Byzantium, Bulgaria, or the Byzantine Black Sea port of Cherson. But he was ambushed by the Pechenegs on his homeward journey and slain in battle close to the Dnieper rapids, in 972.

Tzimiskes returned to Constantinople, taking with him the Bulgarian royal family and great quantities of booty, to celebrate a traditional victor’s triumph in the city. Instead of riding in the imperial chariot drawn by four white horses, he set in his own place of honour a greatly venerated icon of the Virgin, which he had brought with him from Bulgaria; the Emperor himself followed devoutly behind. During the ceremony, Tzimiskes stripped the Bulgarian Tsar Boris of the insignia of royalty, but raised him to the rank of magister in the Byzantine hierarchy. Boris’s brother Romanus was castrated, to disqualify him from attempting to restore the Bulgarian monarchy. The Bulgarian Church now also lost its independent status, at least in eastern Bulgaria. The separate Bulgarian patriarchate was suppressed for the time being after an existence of less than half a century; the Bulgarian Church was re' organized under Greek bishops sent from Constantinople.

68

![]()

(Tsar Samuel and the twilight of empire)

Emperor Tzimiskes distinguished himself further by conquests in Anatolia and the Levant, but perished - probably poisoned - in 976 while still in his prime. The death of this formidable warrior provoked a of sudden revival Bulgarian independence, centred on the western regions of Macedonia. It is a remarkable coincidence that this resurgence of Bulgarian independence was headed by a family of four brothers of wholly or partly Armenian descent - as in the case of Emperor Tzimiskes, who had overthrown the Bulgarian realm of Symeon, Peter and Boris II. These four brothers, David, Moses, Aaron and Samuel, are commonly known as the Comitopuli, their father Nicholas being a provincial comes or count, possibly governor of Sofia. Their mother’s name was Hripsime, a common and exclusively Armenian name, taken from that of one of the holiest martyrs of the early Armenian Church.

Samuel and his brothers raised the standard of revolt in the name of the legitimate Bulgarian king, Boris II, who somehow made his way from Byzantium to Bulgaria, but was accidentally shot dead by a Bulgarian sentry. Two of Samuel’s brothers perished, while Aaron was murdered by his brother Samuel, who suspected him of treason. Thus by the end of the century Samuel was unrivalled master of a new Bulgarian empire, based largely on Macedonia.

Samuel’s empire had its centre first at Prespa, later on at Ohrida, where he re-established the Bulgarian patriarchate, after its various peregrinations to Sofia, Vodena, Moglena and Prespa; as an ecclesiastical centre, Ohrida was to survive Samuel’s empire by several centuries, and is now one of the glories of southern Yugoslavia.

It was not until 993, after several victories over the Byzantines in Thessaly and near Sofia, that Samuel finally assumed the title of Tsar. Samuel conquered the Serbian territories as far as Zara on the Adriatic, and also took the Srem region from the Magyars. Other acquisitions included the northern half of Greece with Epirus, much of Albania, including Dyrrachium (the modern Durazzo) and finally Rascia and Dioclea. In 997, Samuel briefly reoccupied Bulgaria’s original heartland, the region of Pliska and Preslav, and the hinterland of Varna, only to lose it again to the Byzantine emperor, Basil II, in 1001. Geographically, Samuel’s strength lay in the Macedonian kernel of his realm, oriented towards the west and the south, though in most respects Samuel’s short-lived empire was a true successor to that of Tsar Symeon.

69

![]()

After loot, the fortunes of war began to turn against Samuel. Following his successful campaigns against the rebellious aristocracy of Asia Minor, and the Muslim Fatimids in Syria, Basil II undertook a number of campaigns, each of which resulted in the detaching of a province from the Bulgarian empire. Despite the stubborn resistance of the population, in which the Bogomil heretics also played their part, the Greeks systematically reconquered all Bulgaria’s northeastern territories, as well as Thessaly and the regions of Sofia (Sredets) and the Danube stronghold of Vidin. Some of the boyars wavered in their allegiance to Samuel, and began to pass over to the Byzantine emperor.

The fighting continued indecisively for several years. Emperor Basil II took advantage of a lull to reinforce his army, and to bribe more of the Bulgarian magnates to desert Samuel’s cause. In the 1014 campaign in the Belassitsa Mountains, the Bulgarian army was attacked in the rear, taken by surprise and utterly defeated. Fourteen thousand warriors were taken prisoner, and Samuel himself barely escaped with his life. Basil II blinded all the prisoners, except for one man in every hundred, who was to have one eye left, so that he could lead his comrades back home to their sovereign. The terrible sight of these men caused Tsar Samuel to die of shock. Basil’s ruthlessness earned him the title of ‘Bulgaroktonos’ or ‘the Bulgar-slayer’, of which he was very proud.

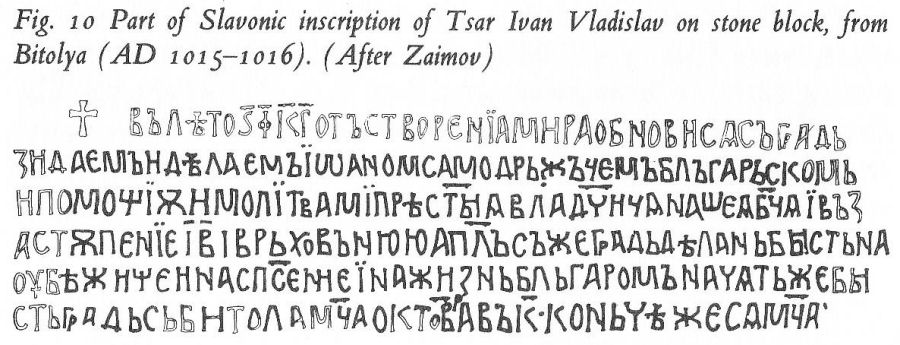

(Fig. 10)

Samuel’s son Gabriel Radomir reigned for only one year, from 1014 to 1015, before being murdered by his cousin Ivan Vladislav, who occupied the throne from 1015 to 1018. Ivan Vladislav who left an important Slavonic inscription at Bitolya to posterity perished in battle at Dyrrachium, thus bringing independent Bulgaria’s death struggle to an end. Basil II made a ceremonial entry into Ohrida, receiving homage from the Tsar’s widow and the other surviving members of the royal house. The whole Balkan peninsula now belonged to the Byzantine Empire, for the first time since the Slavonic migrations almost five centuries before.

Fig. 10 Part of Slavonic inscription of Tsar Ivan Vladislav on stone block, from Bitolya (AD 1015-1016). (After Zaimov)

70

![]()

CHAPTER IV. The Rise and Fall of the Second Bulgarian Empire

The subjection of Bulgaria to direct Byzantine rule lasted rather more than a century and a half, until 1185, though it was punctuated by a series of rebellions.

It must be conceded that the civil policy of Emperor Basil II the Bulgar-Slayer towards the defeated Bulgarians was as moderate as his behaviour towards his defeated foe on the battlefield had been cruel and brutal. In view of the wide-spread devastation throughout the Balkans, Basil exempted the Bulgarians from paying taxes in gold and silver, and accepted instead payment in kind, in the form of beasts, agricultural products and other local commodities.

Byzantium’s newly conquered Bulgarian territory was now divided into administrative districts, which were called ‘themes’. The capital was established at Skoplje, the governor-general of which had the exalted title of ‘strategus’. Among other important provinces was that of Paristrion or Paradunavon on the Danube, with its capital at Silistra. The region on the Adriatic coast, which had belonged to Bulgaria under Tsar Samuel, now formed the theme of Dalmatia. Some years later, around 1067, we find mention of the Byzantine theme or province of Serdica, whose dux was then the future emperor Romanus Diogenes.

The Bulgarian patriarchate of Ohrida was down-graded to an archbishopric. However, the special privileges of this Church foundation were retained under the new dispensation. The Ohrida archbishopric was recognized as autocephalous within the Byzantine hierarchy, and its incumbent was appointed personally by the Byzantine emperor, not by the Oecumenical patriarch of Constantinople.

Vivid, not to say scandalous sidelights on the relations between the Byzantine clerics and their Bulgarian and Macedonian flock are given in the letters of the Greek Archbishop Theophylact of Ohrida, who flourished at the end of the eleventh century and composed a biography of his predecessor, St Clement of Ohrida. In one epistle, Archbishop Theophylact remarks to his correspondent:

71

![]()

By saying that you have thoroughly become a barbarian among the Bulgarians, you, dearest friend, say aloud what I myself dream in my sleep. Because - think of it - how much I have drunk from the cup of vulgarity, being so far away from the lands of wisdom, and how much I have imbibed owing to the prevailing lack of culture! Since we have been living for a long time in the land of the Bulgarians, vulgarity has become our close companion and mate.

The Bulgarians, we gather, had driven Theophylact to drink. In another of these outspoken epistles, he scornfully refers to the Bulgarians as ‘unclean barbarians, smelling of hides, poorer in their way of life than they are rich in evil disposition’. Writing to his subordinate, the Bishop of Vidin, Theophylact exclaims:

And so do not lose heart, as if you were the only one to suffer! Are there Cuman tribes invading your land; What are they, however, in comparison with the local people of Ohrida who come out from the city to attack us! Have you got treacherous citizens; Yours are nothing but children in comparison with our own citizens, Bulgarians that they are!

Genuine sympathy between the Greek master race and the Bulgarian population was assuredly lacking. Latent antipathies flared up after Basil II’s death, largely as a result of the rapacious fiscal policy of Emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian (1034-41). Taxes were steadily increased, and had now to be paid in hard cash. The local Greek governors enriched themselves as quickly as possible and then retired home to enjoy their spoils; peasants were snatched from the fields, and com scripted to fight in remote lands against the foes of the Byzantine Empire.

The financial policy of the central government provoked the Slavs of the Balkans to break out in revolt. When the Slav Archbishop of Ohrida, John, died in 1037, a Greek named Leo was appointed in his place. The rebellion which now broke out soon took on dangerous proportions. A pretender named Peter Delyan, grandson of Tsar Samuel and probably a son of the Bulgarian ruler Gabriel Radomir, was proclaimed tsar in Belgrade in 1040. When Prince Alusianus,

72

![]()

a son of Tsar John Vladislav, who managed to escape from Constantinople, was proclaimed coAuler the insurrection spread throughout the Balkans and northern Greece. Lack of unity among the leaders of this revolt led to its collapse in 1041, after the treacherous Alusianus had enticed Peter Delyan to a banquet and there gouged out his eyes in an ambush.

The second half of the eleventh century was marked by a steady decline in internal security in Bulgaria and the Balkans. The Hungarians attacked the Byzantine Empire from the north, and in 1064 they seized Belgrade. A swarming horde of Tatar nomads, akin to the Pechenegs and known as the Uzes, left the steppes of South Russia and poured through Moldavia into the Balkans in the autumn of 1064. Bulgarian territory, including Macedonia and Thrace as well as northern Greece, was ravaged by these savage invaders. However, a devastating plague, hailed by the pious as a miracle, rid the Empire of most of the Uzes; the survivors either fled across the Danube, or entered the Byzantine service.

The year 1071 brought fresh disasters to Byzantium. In that year,

Bari in Italy fell into the hands of the Normans under Robert Guiscard, while to the east in farthest Armenia, the imperial army commanded by Emperor Romanus was annihilated by the Turks, and Romanus himself captured. Released the following year, he was blinded by his rivals and died before the year was out. Asia Minor, from which derived so much of the strength of the Byzantine armies, was largely overrun by the Seljuq Turks.

All this encouraged insurgents in the Balkans. In 1072, a fresh revolt broke out in the territories which had once formed the nucleus of Tsar Samuel’s domains. The rebels were supported by the principality of Zeta, on the Adriatic; Constantine Bodin, the son of Prince Michael of Zeta, was crowned Tsar in Prizren. In Bulgaria proper, the standard of revolt was raised by the boyar Georgi Voiteh.

Although this revolt was soon crushed, fresh unrest broke out in Bulgaria in 1074, 1079, and again in 1084.

The troubled internal situation was exploited increasingly by the Bogomils (see next chapter), one of whose strongholds was Plovdiv, the metropolis of Thrace. Here Slavs and Greeks lived side by side with numerous Armenians, who had long since introduced their own national

73

![]()

brand of religious heresy, a form of Paulicianism. Partly to combat these heretics the Byzantine ‘Grand Domestic’ or Commander-in-chief in the West, an Armenian adherent of the Georgian Orthodox faith, Gregory Bakuriani or Pacurianos by name, built the magnificent monastery of Bachkovo, south of Assenovgrad (1083). This monastery was placed in the hands of Georgian monks, though later taken over by Greeks and then by Bulgarians. As for the Bogomils and Paulicians, the outstanding Byzantine emperor Alexius Comnenus (1081-1118) devoted much energy to largely fruitless attempts to convert or suppress them, as we read in the Alexiad, a biography written by the emperor’s daughter, Princess Anna Comnena. Many of these Bogomils endured agonizing tortures, or chose to be burnt alive, rather than abandon their beliefs.

(Plate 28)

At the end of the eleventh century, fresh trouble beset the hapless Bulgarians, in the shape of the disorderly hordes of Westerners who passed through the Balkans in the course of the First Crusade in 1096. Their leader was Peter the Hermit, who regarded the Orthodox Bulgarians as heretics, and did nothing to stem the ensuing violence, pillage and arson. The same pattern was repeated at the time of the Second Crusade, in 1147. However, these injuries were to be amply repaid after Bulgaria regained her independence, as we shall see.

(Bulgaria regains independence)

There was little the Bulgarians could do but bide their time, and dream of freedom, as they recalled the heroic age of Tsars Symeon and Samuel. Their moment came in 1185, when the Sicilian Normans attacked the Byzantine possessions along the Adriatic and in Greece, capturing Durazzo (Dyrrachium), and Thessalonica. The last emperor of the Comnenus dynasty, Andronicus, was torn to pieces in Constantinople on 12 September 1185 by an enraged and panic-stricken mob.

The Comnenoi were succeeded by the Angelus dynasty, first in the person of Isaac II (1185-95), of whom it was said that he sold government jobs like vegetables in a market. No sooner had Isaac assumed the purple than he imposed heavy special taxes, on the occasion of his dynastic marriage with the ten-year-old daughter of the King of Hungary.

The Vlachs of the Balkans sent two of their number, the brothers Peter and Assen, to negotiate with Emperor Isaac. The brothers, who owned land and castles in the neighbourhood of Great Tărnovo, made

74

![]()

certain requests for grants of feudal lands and privileges, which were curtly dismissed - a Byzantine courtier even slapping Assen in the face. The infuriated brothers rode swiftly back to Tărnovo. The news of their humiliation spread like wildfire. An uprising was proclaimed in one of the leading churches of the city on the Yantra; and insurrection was soon rife throughout northeastern Bulgaria. The rebellion spread into Thrace, and imperial troops sent to suppress it were three times defeated.

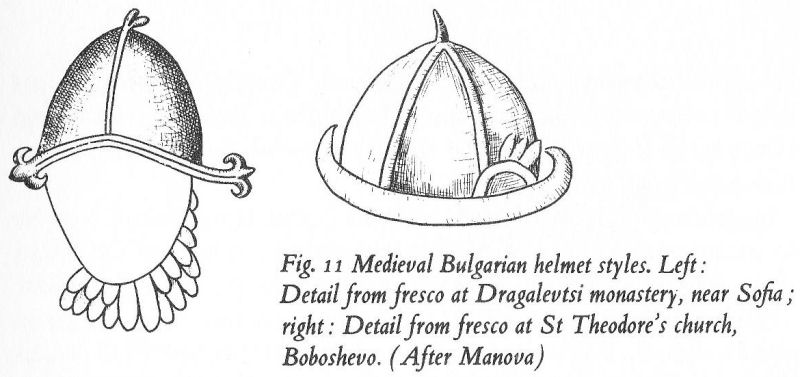

Fig. 11 Medieval Bulgarian helmet styles. Left: Detail from fresco at Dragaletsi monastery, near Sofia; right: Detail from fresco at St Theodore’s church, Boboshevo. (After Manova)

Emperor Isaac himself set out on campaign in 1186, and temporarily drove the insurgent Bulgarians and Vlachs beyond the Danube, into Wallachia. Soon they were back again with Cuman auxiliaries. After a vain attempt to besiege and capture Lovech, Isaac Angelus concluded peace, recognizing the autonomy of the brothers Peter and Assen, and taking with him as hostage a third brother of theirs, the future Bulgarian tsar Kaloyan.

Before long, however, many Bulgarian boyars came to envy Peter and Assen their royal status, and in 1196 the unrest that had been seething erupted. That year Assen was murdered by Ivanko, an ambitious nobleman, and his brother Peter suffered a similar fate a few months later.

The third of the ambitious brothers, Kaloyan, sometimes known as Ioannicius (Ioannitsa), now came into his own. Kaloyan, who reigned from 1197 to 1207, is a key figure in medieval Bulgarian history: his intervention in the struggle between Rome and the Crusaders on the one hand, and the Byzantine empire of Nicaea on the other, proved to be of decisive importance. Kaloyan was anxious to establish the legitimacy of his rule, and from 1199 kept up an interesting correspondence with Pope Innocent III, culminating in the sending of a papal legate,

75

![]()

Bishop John de Casemaris, from Rome to Tărnovo. On 7 November 1204, the Legate consecrated the Bulgarian Archbishop Basil as primate and patriarch of Bulgaria, and the next day placed the royal crown on Kaloyan’s head.

However, Bulgarian relations with the Latins at this period were by no means uniformly cordial. The marauding activities of the Third Crusade passing through Bulgaria in 1189 were particularly resented. The Crusaders suspected the Byzantine emperor of instigating Bulgarian guerilla fighters. In a letter to his son and successor, Henry VI, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa reported that thirty-two Bulgarians had been hanged in a single day, ‘suspended like wolves’, and that their comrades had shadowed the Crusaders as far as Plovdiv, molesting them with nocturnal raids through all the Bulgarian forests. ‘Yet our army in turn dreadfully tortured great numbers of them with various kinds of torments.’

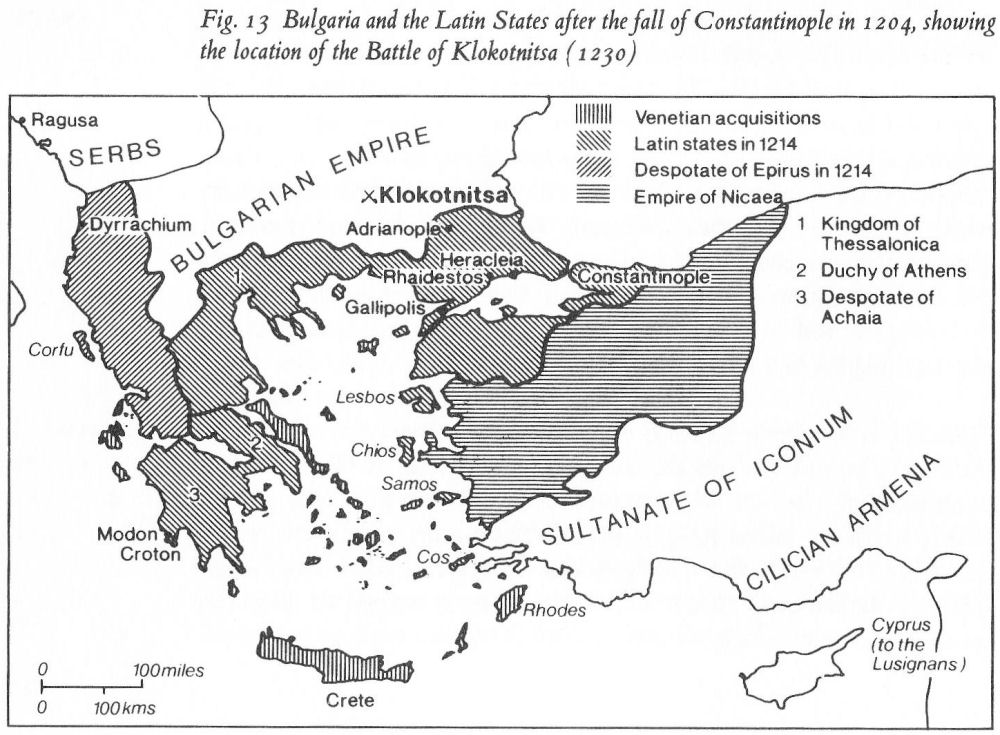

Byzantium finally fell to the Crusaders in 1204, and Baldwin of Flanders set himself up as emperor. Tsar Kaloyan at first adopted a conciliatory policy towards the Latin Empire of Constantinople. How' ever, the Latins were haughty; they informed Kaloyan that the Balkans belonged to the Byzantine sphere of authority, and that they considered Kaloyan and his subjects to be their vassals. The Bulgarian tsar there' upon allied himself with various dissatisfied Greek nobles, and invaded Thrace. In a great battle, fought in 1205 near Adrianople, the Crusaders were decisively defeated. Emperor Baldwin was taken prisoner. Accord' ing to one account, he was imprisoned for life in the Baldwin Tower on the Tsarevets acropolis at Tărnovo. The Latin Empire never fully re' covered from this shattering blow; the Greeks were enabled to maintain the rival empire of Nicaea, which remained the leading stronghold of Greek culture and political power until the downfall of the Latin regime in Constantinople, in 1261.

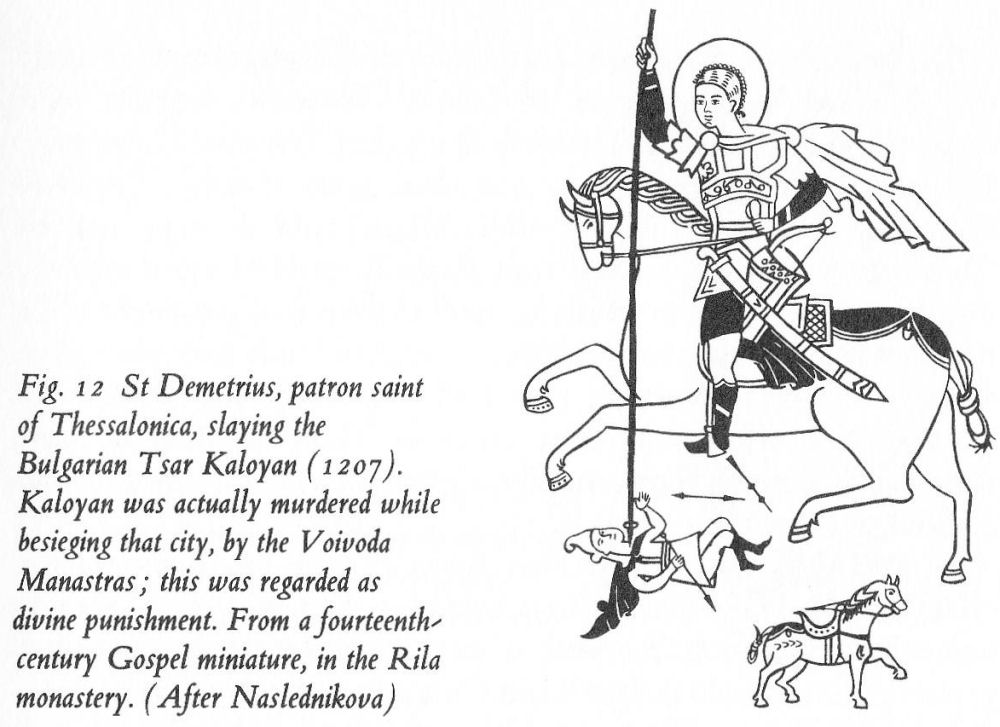

Copying the example of the Byzantine emperor Basil the Bulgar' Slayer, Kaloyan styled himself ‘the slayer of Romans’. In 1207 he marched westwards and rapidly conquered most of Macedonia. In September of that year, he ambushed and slew the Crusaders’ leader Boniface of Montferrat. Two months later, as he was besieging Thessalonica, Kaloyan was murdered in his tent by the Cuman Voivoda Manastras, a move instigated by dissident Bulgar boyars.

(Fig. 12)

76

![]()

Fig. 12. St Demetrius, patron saint of Thessalonica, slaying the Bulgarian Tsar Kaloyan (1207). Kaloyan was actually murdered while besieging that city, by the Voivoda Manastras; this was regarded as divine punishment. From a fourteenth-century Gospel miniature, in the Rila monastery. (After Naslednikova)

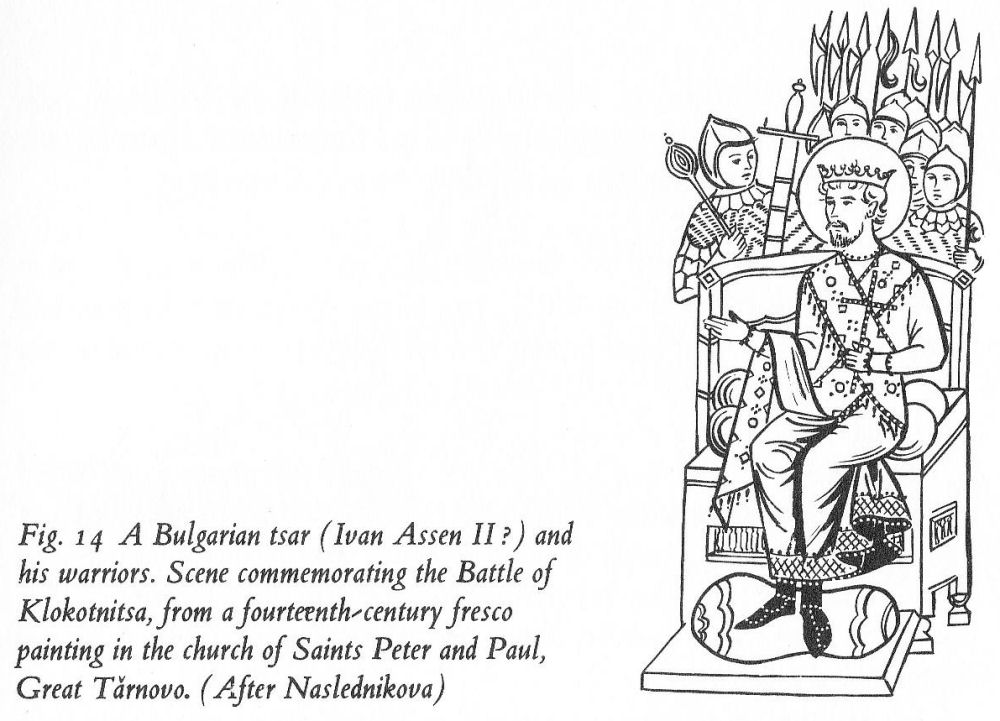

The boyars set on the throne a nephew of Kaloyan, Boril by name (1207-18). An unpopular and feeble ruler, Boril is chiefly remembered for the Church council which he summoned in 1211 to try and root out the Bogomil heresy. The Bogomils identified themselves with the oppressed and impoverished peasants and townsfolk, and enjoyed considerable popular support. Boril’s persecutions, as well as his military ineptitude, led to a revolt in Vidin. In 1218, the son of Tsar Assen I, by name Ivan Assen, returned from exile in Russia at the head of a company of Russian and Cuman mercenaries, and also a Bulgarian contingent. The citizens of Tărnovo opened their gates to him; Tsar Boril was deposed and blinded, and Ivan Assen began his victorious and brilliant reign as tsar which lasted until 1241.

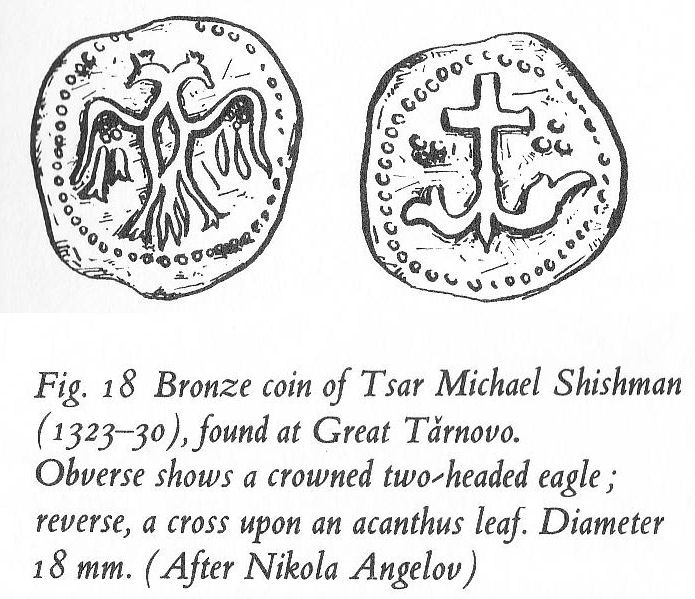

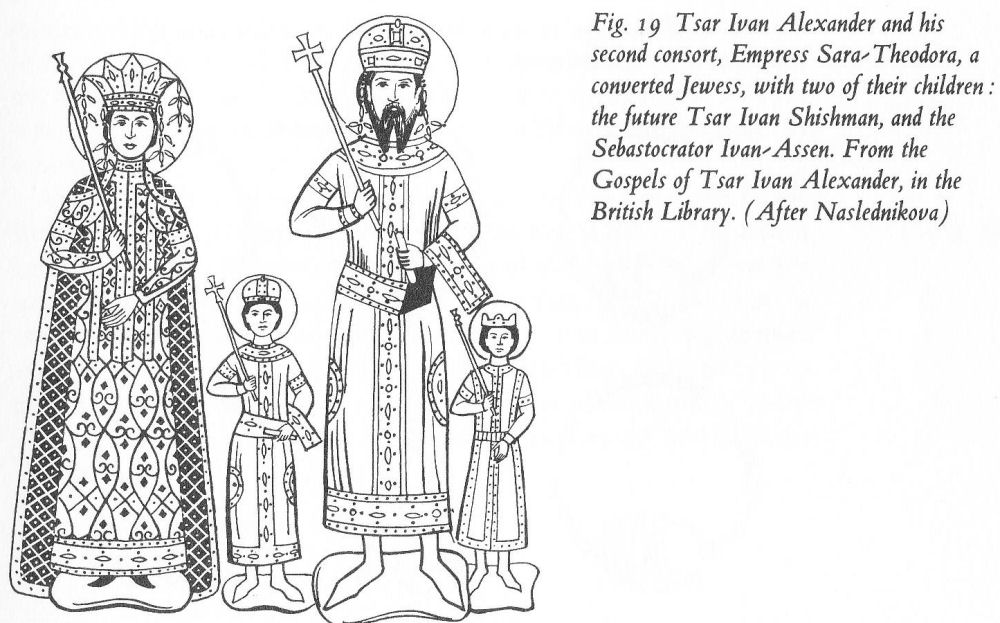

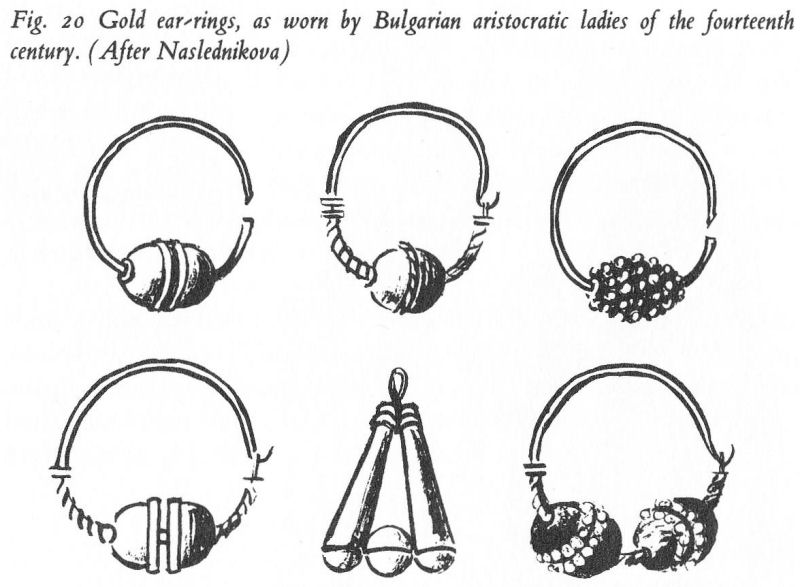

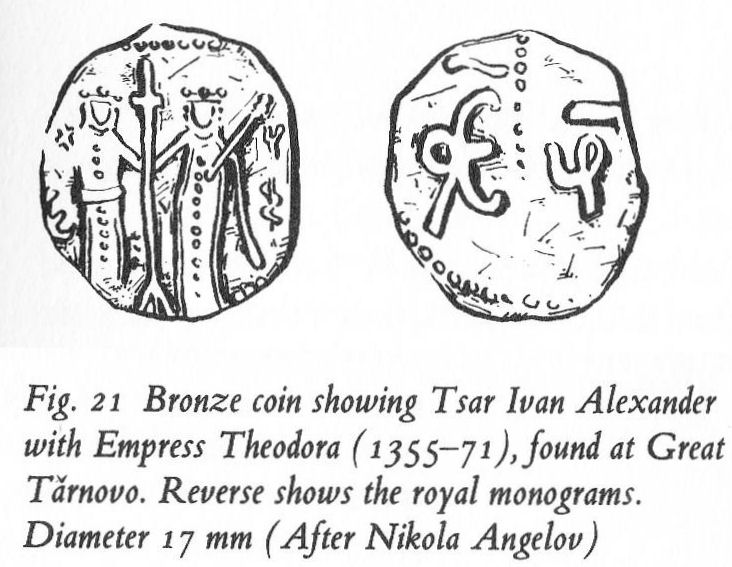

(Achievements of tsar Ivan Assen II)