II. MACEDONIA BETWEEN THE TWO WARS

1. Bulgarian-Yugoslav relations 21

2. Bulgarian-Greek relations 29

3. Salonika 34

4. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization 36

5. The communists and Macedonia 45

1. BULGARIAN-YUGOSLAV RELATIONS

Relations between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia between the two wars, which were largely, though by no means entirely determined by the Macedonian question, may be considered in three phases. From 1919 until 1923, while the Agrarian, Stambulisky, was in power in Bulgaria, a real effort was made to reconcile the two countries and to forget the Macedonian issue, or even to solve it through South Slav Federation. The second phase, from the murder of Stambulisky in 1923 until the Military League coup in Bulgaria in 1934, was a period of strained relations and sometimes of dangerous tension, mainly as a result of the Bulgarian authorities’ toleration of I.M.R.O. From the suppression of I.M.R.O. in 1934 until early in 1941, relations were correct and at times even friendly, though the ghost of the Macedonian dispute still barred the way to full solidarity between the two Balkan Slav States.

Through most of the period between the two wars Italy, who wanted to weaken or disrupt Yugoslavia and so gain control of the Adriatic, tried with varying degrees of intensity to prevent any reconciliation between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. She encouraged Bulgarian revisionism and subsidized I.M.R.O. From the early thirties onwards Nazi Germany was interested in preventing Balkan solidarity except under German control, but does not seem to have exploited the Macedonian dispute until she handed over most of Yugoslav Macedonia to Bulgaria in April 1941.

France consistently backed Yugoslavia, whom she regarded as her protégé; and both France and Britain tried at intervals to reconcile Yugoslavia with Bulgaria, to restrain Bulgarian, or Macedonian, excesses, and later to promote a Balkan bloc, including Bulgaria, against German aggression. Soviet Russia had very little direct influence on Yugoslav-Bulgarian relations, but through the Comintern kept a close grip on the Communist

21

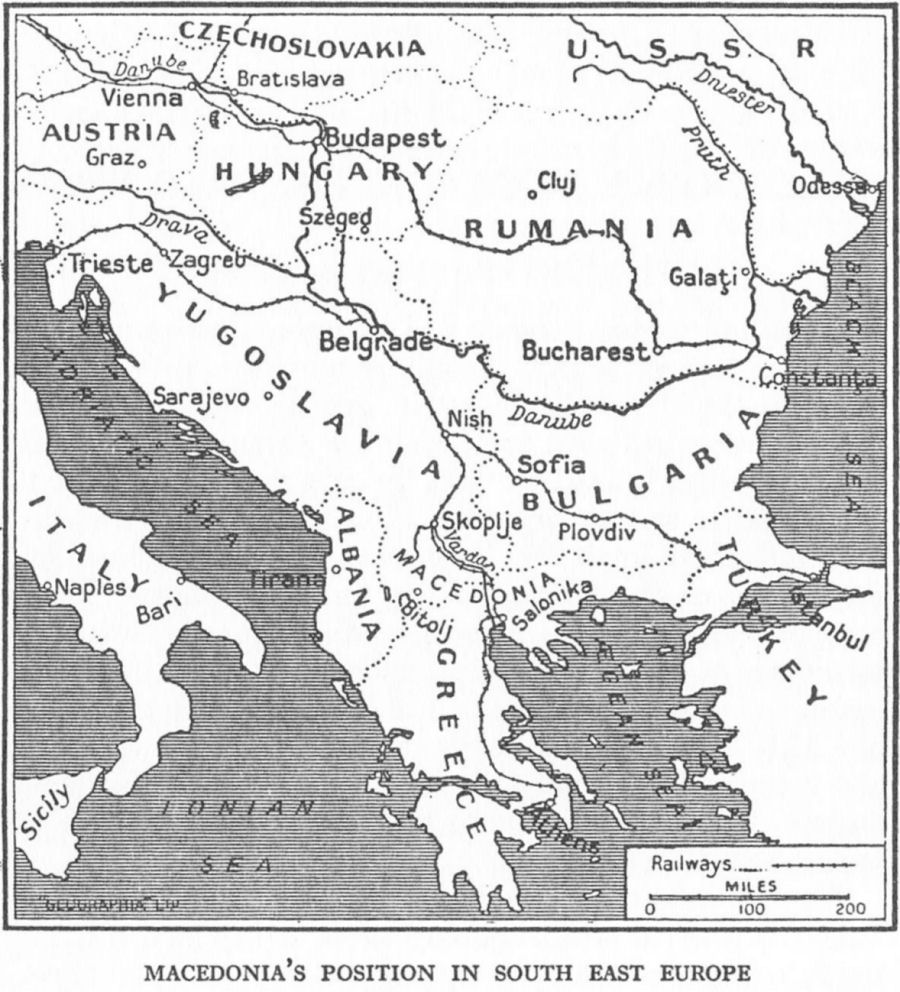

![]()

Macedonia’s position in south east Europe

Parties of both countries. At the same time, through the Comintern, Russia took an especial interest in the cause of Macedonian autonomy, because of its revolutionary potentialities, and in 1924 made an abortive attempt to capture I.M.R.O. The Bulgarian royal house, for dynastic reasons, was at first hostile, and later reserved, towards any close co-operation with Yugoslavia.

In spite or because of all these conflicting influences, Bulgaria in 1941 made exactly the same choice as in 1915: she sided with Germany to obtain Yugoslav Macedonia.

The new Yugoslavia’s treatment of Yugoslav Macedonia, at least until 1929, was well calculated to play into the hands of Bulgarian revisionism and of I.M.R.O. The Yugoslav authorities eliminated the name ‘Macedonia’. Yugoslav Macedonia became

22

![]()

‘South Serbia’ or, after King Alexander’s administrative reforms, the ‘Vardarska Banovina’. All Slav Macedonians were declared to be Serbs, some of them perhaps regrettably and temporarily Bulgarized. The Church came under the Serbian Patriarchate, and Serbian was the official language in administration and the schools. The Government sent settlers, mainly Serbs, to colonize land taken from Turkish landlords or under-developed areas; and the Serbian settlers caused great resentment among the Macedonian population. Most important of all, in the early years the Belgrade Government tended to send its least competent and honest officials from Serbia to Macedonia, where service was unpopular and pay was bad. Little money was invested in Macedonia except for a few showy buildings in Skoplje, the provincial capital.

Yugoslavia was bound by peace treaty obligations to respect the rights of her minorities; but since she denied that the Macedonians constituted a minority, repeated appeals to the League of Nations by genuine or alleged Macedonian representatives (often resident in Sofia) were fruitless.

I.M.R.O.’s organization of komitadji attacks over the frontier from Bulgaria, and of terrorist acts in Yugoslav Macedonia, inevitably provoked the Yugoslav authorities to repressive measures and reprisals against the local Macedonian population. These heightened the resentment of the people of Yugoslav Macedonia; but in the end they grew tired of I.M.R.O. and accepted arms from the Yugoslav authorities to protect their villages against komitadji attacks.

After King Alexander instituted his dictatorship in January 1929, he genuinely tried to introduce reforms in ‘South Serbia’ and to send a better type of official there, or even to employ local officials and teachers. The Macedonians began to settle down and to accept Yugoslav rule passively, if without enthusiasm. But pro-Bulgarian feelings lived on and made it easy for the Bulgarians to secure willing initial acceptance of the Bulgarian occupation in 1941, and difficult for Tito to win the Macedonians back for Yugoslavia.

Between the two wars the population of Yugoslav Macedonia was not allowed to form any Macedonian political organization. In the first post-war elections in 1920, when all over Yugoslavia the Communists had big successes, the Macedonians elected

23

![]()

seventeen Communist deputies. But this was a protest against their new Government rather than an expression of genuine Communist sympathy. Later, when the Yugoslav Communist Party had been banned, they usually voted, of necessity, for one or other of the Serbian political parties or, after 1929, for the official government list. There is no evidence that Communism was strong or well organized inside Yugoslav Macedonia between the wars; the local Communist organization was obviously very weak in 1941.

In Bulgaria, Stambulisky seized power after defeat in the First World War with the reputation of being an advocate of South Slav union, of ‘an integral, democratic, and pacific Yugoslavia from Mount Triglav to the Black Sea’. He is said to have sympathized with the Macedonian Federalists and the idea of an autonomous Macedonia; he is even reputed to have said that he would surrender Bulgarian Macedonia to an autonomous Macedonia. [1]

Stambulisky was naturally hated by the I.M.R.O. leaders. In 1919 he even arrested the two chiefs, Todor Alexandrov and General Protogerov; but both escaped. The next year Alexandrov was busy reorganizing I.M.R.O. and instigating komitadji raids in Yugoslav Macedonia, and to a lesser extent in Greek Macedonia. Stambulisky, preoccupied with his own agrarian revolution at home, could do little to stop him.

By June 1922 things had reached such a pitch that the Yugoslav Government informed the Bulgarian Minister in Belgrade that they could not permit attacks by Bulgarian komitadjis in Yugoslav territory, that they would take no responsibility for the grave consequences that might ensue, and that they had drawn the attention of the Allied Governments and the League of Nations to the situation. On 14 June the Roumanian Foreign Minister, returning from a meeting in Belgrade with the Foreign Ministers of Yugoslavia and Greece, presented a collective note to the Bulgarian Minister in Bucharest accusing the Bulgarian Government of tolerating or even encouraging komitadji activities. Stambulisky’s Government replied by sending a letter to the Secretary-General of the League of Nations, drawing the attention of the League Council to these circumstances ‘as being likely to affect relations between Bulgaria and her neighbours’,

1. J. Swire, Bulgarian Conspiracy (London, Hale, 1939), p. 142.

24

![]()

and proposing an International Commission of Inquiry. The Bulgarian Note added that Bulgaria had done all she could to provide for frontier security, but as she had only 10,716 troops, her forces were inadequate; and stated that Stambulisky had never encouraged the komitadji bands and had in fact tried to strengthen frontier control on Bulgaria’s south-west frontier.

The matter was smoothed over by the League of Nations, since the Yugoslav, Greek, and Roumanian representatives took a moderate attitude. Perhaps they thought that Stambulisky’s Government was more well-meaning than any alternative Bulgarian regime was likely to be, and that he should therefore not be pressed too hard. No Commission of Inquiry was sent to Macedonia.

In spite of this diplomatic affray, Stambulisky pursued his aim of reconciliation with Yugoslavia. After negotiations conducted by his Minister in Belgrade, the Agrarian, Kosta Todorov, he concluded the Nish Convention which came into force in May 1923. This provided that Yugoslavia and Bulgaria should institute joint measures of frontier control to prevent raids. For 100 metres on each side of the frontier all trees and undergrowth were to be cleared, and suspected sympathizers of the komitadjis were to be banned from the frontier zones, but farmers owning land on both sides of the frontiers were to have special passes.

The Nish Convention naturally produced a violent I.M.R.O. reaction. Stambulisky attempted to fulfil its spirit by carrying out arrests in the Petrich and Kustendil districts, the chief I.M.R.O. strongholds. The I.M.R.O. leaders conspired with a military group, the Officers’ League (then led by Colonel Volkov) and with the former Socialist, Professor Alexander Tsankov (later Hitler’s puppet). In June 1923 these allies carried out a coup: Stambulisky was brutally murdered and many of the other Agrarian leaders fled to Belgrade. Tsankov became Prime Minister with Volkov as his Minister of War. The first inter-war phase of Yugoslav-Bulgarian relations, the phase of attempted reconciliation, was over. And for the next decade I.M.R.O. had an invaluable ally, or perhaps master, in Volkov, who managed to retain control of the Bulgarian War Office through all vicissitudes.

Tsankov, however, started his period of office by declaring that he would respect the Nish Convention. In October 1923 a mixed Bulgarian-Yugoslav Commission, appointed under the

25

![]()

terms of the Convention, met in Sofia, and in November signed an agreement on extradition, medical aid, and compensation for requisitioning carried out by the Bulgarian occupation authorities in Serbian Macedonia during the past war. The Bulgarian Parliament ratified the agreement in January 1924; but nevertheless komitadji attacks and terrorist action in Yugoslav Macedonia continued. In 1926, after the Tsankov Government had begun to talk of closer relations with Yugoslavia, Tsankov was defeated in Parliament. His successor, Liapchev, was himself a Macedonian, and, with Volkov as his War Minister, gave I.M.R.O. full protection.

In June 1927 the League of Nations rejected one of the periodic appeals by Macedonian organizations against alleged Yugoslav misrule. Early in 1928 it was reported that the British Legation in Sofia had presented the Bulgarian Government with a list of members of I.M.R.O. suspected of intending to cross the Yugoslav frontier to commit acts of violence. In July 1928 two things happened: the I.M.R.O. leader, Protogerov, was assassinated on the order of the rival leader, Ivan Mihailov; and an I.M.R.O. would-be assassin attempted unsuccessfully to shoot the Chief of the Belgrade Police, Mr Zhika Lazich. Britain and France seized the chance to make a joint demarche to Liapchev’s Bulgarian Government against an I.M.R.O. weakened by internal division. The demarche provoked a prolonged cabinet crisis in Sofia; the Foreign Minister, Atanas Burov, threatened to resign unless the pro-I.M.R.O. War Minister, General Volkov, were removed; but Tsar Boris supported Volkov, and Liapchev eventually formed a new Government with Volkov again as War Minister. So nothing was achieved.

The Italian Minister in Sofia had refused to join with his western colleagues in making this démarche, saying that his country did not wish to interfere in Bulgarian affairs on Yugoslavia’s behalf.

In 1929 Yugoslavia made a definite attempt to conciliate Bulgaria. In January King Alexander instituted his dictatorship, and presumably decided that he must strengthen his somewhat shaky position by easing relations with Bulgaria. In February the Yugoslavs partially reopened the frontier, which about a year earlier they had attempted to seal hermetically with a barbed wire barrier and a system of blockhouses. Also in February,

26

![]()

a Bulgarian-Yugoslav Mixed Commission met at Pirot and reached partial agreement on properties lying on both sides of the frontier, and on other lesser questions, but disagreed on the width of a proposed neutralized frontier zone from which all suspected Macedonian revolutionaries were to be banned. The Bulgarians insisted that 500 metres was sufficient, but the Yugoslavs wanted a much deeper zone.

In spite of this difference, a form of agreement was concluded at Pirot. But in April the Croat extremist, Ante Pavelić (later an accomplice in King Alexander’s murder, and later still head of the puppet Croat State created in 1941) paid a public visit to Sofia, as the guest of the National Committee of Macedonian Refugees. He was enthusiastically acclaimed—obviously as an enemy of Yugoslavia—and was even received by the Government. This visit caused great excitement in Yugoslavia, and the Yugoslav Government protested in Sofia and postponed ratification of the Pirot Agreement. However, further meetings were held in Pirot in September, and a new agreement was concluded and came into force in November 1929, after which a Mixed Commission met in Sofia.

I.M.R.O. celebrated the Pirot Agreement by attacking the Orient Express between Tsaribrod and the Bulgarian frontier on 23 November. This provoked another Yugoslav protest. And, although I.M.R.O. was now devoting rather more energy to its internal blood-feuds than to terrorism in Yugoslavia, relations between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria remained strained until 1933.

King Alexander then made a fresh conciliatory gesture. When King Boris passed through Belgrade in September 1933, King Alexander greeted him at the station. It was the first time the two Kings had met since the First World War. Then at the beginning of October King Alexander visited Boris at his Black Sea home at Euxinograd. In December King Boris, with Queen Ioanna and the Bulgarian Prime Minister, Nikola Mushanov (who had taken office three months after Liapchev’s defeat in 1931, but had carried on the policy of tolerance of I.M.R.O.), were welcomed in Belgrade. Yet when the Balkan Pact was initialled in Belgrade by Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, and Roumania in February 1934, Bulgaria stood apart. To have joined the Pact would have meant abandoning her Macedonian claim.

27

![]()

There were probably two motives behind Bulgaria’s somewhat ambiguous foreign policy at this period. First, Italy was now preoccupied with her Abyssinian dream of conquest, and so less concerned with making trouble for Yugoslavia. On the other hand Nazi Germany was now beginning to plan her penetration of the Balkans, and so had an interest in keeping the Balkan countries divided and preventing their consolidation in a bloc which might eventually be hostile to Germany. Thus although in the six years preceding the Second World War Bulgaria developed a friendly attitude towards Yugoslavia, she always kept aloof from the Balkan bloc. The growing prospect of a fresh European upheaval helped to deter her from renouncing her claim to Yugoslav Macedonia and also to an Aegean outlet.

In 1933 I.M.R.O. was naturally alarmed at Bulgarian- Yugoslav rapprochement; and in the Spring of 1934 there were rumours in Sofia that it would carry out a coup against the Mushanov Government. For this, and no doubt also other reasons, the Military League, a group of reserve officers headed by Colonel Damian Velchev and Kimon Georgiev, together with Zveno, a group of progressive but authoritarian-minded intellectuals, carried out their coup on 19 May 1934.

The coup was executed smoothly and efficiently and a new Government under Georgiev was formed with the reluctant consent of King Boris, who was powerless to resist. The new Government wanted friendship with Yugoslavia; and almost their first act was to order the disbandment of revolutionary organizations, including both I.M.R.O. and the followers of the late General Protogerov. They sent troops to clear up the Petrich Department (Bulgarian Macedonia), which had been I.M.R.O.’s base and stronghold. The operation was carried out with surprising ease. The I.M.R.O. leader, Ivan Mihailov, fled to Turkey, and other prominent Macedonians were interned or arrested. Inside Bulgaria I.M.R.O. virtually ceased to exist as an organization, so that it could no longer poison Yugoslav-Bulgarian relations.

The suppression of I.M.R.O. led to an immediate improvement in the relationship of the two countries. In September 1934 King Alexander and Queen Marie paid a ceremonial visit to Sofia. Though elaborate precautions had to be taken to protect the king from assassination, the visit passed off smoothly. But

28

![]()

when a few days later, on 9 October, he drove through the streets of Marseilles, he was assassinated by Chernozemski, a member of I.M.R.O. who was in league with the Croat Ustashi and who had been preparing for the deed in Hungary. Italy protected Chernozemski’s Croat confederates from punishment.

Since I.M.R.O. had been put down in Bulgaria five months earlier, the killing of King Alexander did not produce a crisis in Bulgarian-Yugoslav relations. When 6,000 Yugoslav Sokols (the patriotic gymnastic organization) visited Sofia in July 1935, they were welcomed with great enthusiasm. In spite of Bulgaria’s aloofness from the Balkan Pact, in January 1937 she signed a Treaty of Perpetual Friendship with Yugoslavia—a development which caused considerable uneasiness to Yugoslavia’s cosignatories of the Pact. Also in 1937 Italy signed a Treaty with Yugoslavia; and Germany, with her growing interest in economic exploitation of the Balkans, seems to have used her influence at this period to prevent Bulgarian-Yugoslav quarrelling over Macedonia. The Macedonian question dropped out of international politics for the next four years.

It seems likely that right up until March 1941 Germany hoped to drive Bulgaria and Yugoslavia in harness together in spite of the traditional Macedonian barrier between them. To achieve this, Germany was willing to offer Yugoslavia an Aegean outlet in Salonika rather than offer Yugoslav Macedonia to Bulgaria. But the Yugoslav coup d’état of 27 March 1941 upset Germany’s plans, which had to be switched over rapidly to the invasion of Yugoslavia. In this Bulgaria was invited to participate, receiving in return the right to occupy Yugoslav Macedonia, except for a small area in the west which fell to Italian-occupied Albania, and the less welcome duty of occupying part of Serbia. Germany, however, did not allow Bulgaria formally to annex Macedonia, holding the card of Macedonian autonomy up her sleeve for future contingencies.

2. BULGARIAN-GREEK RELATIONS

Greek feelings towards Bulgaria at the end of the First World War were very bitter. The Bulgarian occupation authorities in Greek eastern Macedonia had behaved towards the Greek population with brutality singularly inappropriate in supposed liberators.

29

![]()

An Inter-Allied Commission in 1919 reported that ninety-four villages had been entirely demolished, that 30,000 people had died of hunger, blows, and disease during the occupation, that 42,000 had been deported to Bulgaria, and that 16,000 had fled to Greece.

The Allied Powers realized that early reconciliation was out of the question. Accordingly, in addition to the Treaty of Neuilly, a Greek-Bulgarian Convention was concluded on 27 November 1919 providing for a voluntary exchange of population,

e. the Greeks of southern Bulgaria for the Bulgarian (or Slav Macedonian) minority of Greek Macedonia.

The Greeks had earlier proposed drafting a tripartite treaty for reciprocal emigration of racial minorities between Greece, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia. But on 8 November the Yugoslav delegate at Paris had declined, saying that his Government preferred bilateral negotiation. [1]

Under the Greek-Bulgarian Convention, emigrants were to lose their old nationality and acquire the nationality of the country to which they had emigrated. They were to be allowed to keep their movable property and a League of Nations Mixed Commission was to liquidate immovable property.

Both countries, for different reasons, welcomed the Convention, but it was opposed by I.M.R.O., whose leaders presumably felt, rightly, that the exchange would seriously weaken Bulgaria’s ethnographical claim to Greek Macedonia. I.M.R.O. forbade the Bulgarians (or Slav Macedonians) of Greece to take advantage of the Convention. [2] The Greeks of Bulgaria, threatened by Stambulisky’s land reform, were more willing to move, but things progressed slowly. The Commission was set up in 1920 and only finished its work in 1932. By June 1923 only 197 Greek families and 166 Bulgarian families had filed declarations of emigration. [3] Then the Greek Government, claiming military necessity arising from the Greek-Turkish war, deported several thousand Bulgarian families from Thrace, and put Greek refugees from Turkey in their place. This started up a migration of populations

1. S. R. Ladas, The Exchange of Minorities: Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey (New York, Harvard University and Radcliffe College Bureau of International Research, 1932), p. 36.

2. C. A. Macartney, National States and National Minorities (London, Oxford University Press for the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1934), p. 439; Ladas, op. cit. p. 104.

3. Macartney, op. cit. p. 440.

30

![]()

in very strained conditions in the years 1923-4. Finally, about 52,000 Bulgarians (or Slav Macedonians [1]) of eastern Macedonia left Greece, and about 25,000 Greeks left Bulgaria. [2] The result was that Greek eastern Macedonia was virtually cleared of Slav Macedonians, while most of those living west of the Vardar chose to stay in Greece. There thus continued to be a ‘Slavophone’ minority in the region bordering on Yugoslavia, around Kastoria, Fiorina, Edessa, and other towns of the area.

In the Greek census of 1928, 81,984 persons registered as Slav-speaking. One Greek estimate of the present number is ‘about 100,000’. [3] (For an estimate suggesting a higher number, see above, p. 12.) On the whole the ‘Slavophones’, mostly small peasants living in remote villages, not in the towns, settled down fairly peacefully in Greece, at least until the Axis invasion of the Balkans in 1941, which revived old pro-Bulgarian or pro- Macedonian sympathies.

On 29 September 1924 Greece and Bulgaria signed a Protocol known as the Kalfov-Politis Agreement, placing the ‘Bulgarian’ minority in Greece under League of Nations protection. But the Yugoslav Government, which did not admit the existence of a Bulgarian or Macedonian minority in Yugoslavia and regarded the Greek precedent as dangerous, made strong representations and on 15 November denounced the Greek-Serbian Treaty of 1913, as a mark of displeasure. [4] On 15 January 1925 the Greek Government announced that they did not intend to put the Protocol into operation. [5] Thereafter the Greek Government treated the ‘Slavophones’ as Greeks without any special minority rights. Up till 1941, there was little indication that this policy caused resentment among the ‘Slavophones’ who, without the upheaval of the Axis invasion, might presumably in time have been peacefully assimilated.

The League of Nations Mixed Commission for the population exchange, in spite of great difficulties and delays, completed its task of liquidating immovable property. Ten per cent of the indemnities were paid in cash and the rest in State bonds. Both

1. Macartney, op. cit. p. 530.

2. A. A. Pallis, ‘Macedonia and the Macedonians’, p. 8.

3. Pallis, op. cit. p. 8.

4. ibid., p. 11, quoting P. Pipinelis, History of Greek Foreign Policy 1923-41.

5. A. J. Toynbee, Survey of International Affairs 1926 (London, Oxford University Press for the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1927), p. 165.

31

![]()

Greek and Bulgarian Governments complained of the burden laid upon them by the exchange. [1] What caused most indignation among Macedonians in Bulgaria was the Mixed Commission’s decision in 1927 to liquidate the ecclesiastical and scholastic property of the Bulgarian communities in those villages of Greek Macedonia from which the majority of Bulgarians (Slav Macedonians) had emigrated, either voluntarily or compulsorily. However, the Bulgarian Foreign Minister of the time, Mr Burov, who was not sympathetic to the Macedonian cause, said that to maintain them would only be ‘sentimental nonsense’, and the Prime Minister, Mr Liapchev, despite his own Macedonian sympathies, supported Burov’s stand. All the Macedonians of Bulgaria could do was to hold protest meetings.

In addition to the Greek-Bulgarian exchange, which was theoretically voluntary, there was the Greek-Turkish compulsory exchange of populations from 1923 onwards. This had an even more profound effect on the character of Greek Macedonia. Under the Lausanne Agreement between Greece and Turkey,

Greeks from Asia Minor were settled in Greek Macedonia. At the same time 348,000 Turks left Greek Macedonia. The newly-arrived Greeks were in general energetic and hardworking; they raised the productivity of eastern Macedonia and made it the main grain-producing area of Greece. Ethnographically, they made the population of Greek Macedonia, according to the 1928 Greek census, 88.1 per cent Greek. [2] Originally many of them showed sympathies with Communism, but these did not lead them in the direction of Macedonian autonomy. The Comintern had in 1922 come out strongly against the settlement of Greek refugees in Macedonia and Thrace, on the grounds that it would destroy the ethnological character of these areas; but the Comintern appears to have had very little influence in the matter.

In general the settlement of the Asia Minor refugees enormously strengthened Greece’s hold on Greek Macedonia, and made the old idea of a greater united Macedonia stretching down to the Aegean seem, in the inter-war period, no more than an outworn fantasy.

Perhaps it was for this reason that relations between Greece

1. Macartney, op. cit. p. 443.

2. Pallis, op. cit. p. 9.

32

![]()

and Bulgaria, though very far from friendly, were seldom as tense as were Bulgarian-Yugoslav relations. To operate successfully in Greece, I.M.R.O. would have required a friendly Slav population close to Bulgaria’s borders; but it could have no hope of gaining local support from Greeks. So although in the early years after the First World War I.M.R.O. tried to organize resistance in Greek Macedonia as well as in Yugoslav Macedonia, it soon concentrated on the latter.

In June 1922 Greece joined with Yugoslavia and Roumania in the joint representations made to the Stambulisky Government over komitadji raids.

A much more serious clash came in October 1925, when General Pangalos was dictator in Greece. After a frontier incident in which a Greek soldier was shot, Greek troops crossed the border at Kula and shelled the nearby Bulgarian town of Petrich. The local I.M.R.O. ‘militia’ mobilized, obtained arms from Bulgarian army depots, and resisted the Greeks. On 24 October, three days after the first clash, the League of Nations ordered the Greeks to suspend hostilities; after a little more firing the Greeks withdrew from Bulgarian soil five days later. [1] A League of Nations Commission of Inquiry found that Greece had violated the League Covenant and ordered her to pay £45,000 indemnity to Bulgaria. A scheme for neutral supervision of the Bulgarian- Greek frontier under Swedish officers was agreed.

In 1930, on the initiative of Venezelos, an attempt was made to draw Bulgaria into the orbit of talks which had then been proceeding for some time about the possibility of a Balkan Pact. A Balkan Conference of Albanian, Bulgarian, Greek, Yugoslav, Roumanian, and Turkish representatives met in Athens in October. The Macedonian problem was deliberately excluded from the agenda. However, outside the conference-room Venezelos told Bulgarian journalists, in an interview, that a settlement of the ‘minorities problem’ was one of the essential conditions for a Balkan Federation. [2] This unofficial half-promise was never followed up in practical terms; so that Bulgaria stayed outside the Balkan Pact when it was concluded four years later.

In the nineteen-thirties, attempts at rapprochement between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia almost inevitably caused nervousness in

1. Swire, Bulgarian Conspiracy, p. 202.

2. Survey of International Affairs 1930, p. 150.

33

![]()

Greece. The Greeks feared that the foundation of a South Slav bloc, or of a South Slav Federation, on her northern border would be a threat to her security. It might also pave the way for renewed demands on Greek Macedonia and a revival of the medieval Slav thrust to Salonika.

3. SALONIKA

The subject of Slav access to the Aegean at Salonika was one which Greece found particularly delicate. Following the Greek- Serbian Alliance at the time of the Second Balkan War in 1913, a Greek-Serbian Agreement was signed in the Spring of 1914, assigning a free zone in Salonika port to Serbian commerce. The First World War postponed ratification of this Agreement. After the war, in November 1922, M. Politis visited Belgrade, and Greece ratified the 1914 Agreement on 21 November. A month later, however, Yugoslavia refused to ratify it on the ground that it offered insufficient guarantees.

Fresh negotiations were started and on 10 May 1923 a new agreement was signed in Belgrade to regulate transit through Salonika. By this Greece was to cede to Yugoslavia for a term of fifty years an area to be called the ‘Salonika Free Zone’. This was to be at Yugoslavia’s disposal and under her customs administration, although it was to remain an integral part of Greek territory and under Greek sovereignty. The officials within the Zone were to be Yugoslavs.

Ratifications of this 1923 Agreement were exchanged on 30 May 1924, and the Zone was handed over to the Yugoslavs on 6 March 1925.

In 1923 Greece also made a similar offer to Bulgaria. Private talks between Greek and Bulgarian delegates had taken place at the time of the Lausanne peace conference which started in November 1922. As a result on 23 January 1923 Venezelos offered Bulgaria a Free Zone in the port of Salonika on the same terms as Greece was then offering to Yugoslavia. However, M. Stanciov, the Bulgarian delegate, said that the terms of the proposal were inadequate and that he did not wish to reopen discussion of the question. Negotiations then ceased. [1]

In March 1926, during the session of the League of Nations,

1. Survey of International Affairs 1920-23, pp. 340 ff.

34

![]()

the Greek and Bulgarian delegates again had talks. Fresh Greek offers of a Free Zone at Salonika were made. Bulgaria, however, preferred to insist on her claim to an Aegean outlet in Thrace. [1]

Meanwhile a fresh disagreement had arisen between Greece and Yugoslavia over Salonika. The Yugoslavs considered the Greek freight rates on the railway from Djevdjelija, on the Greek- Yugoslav frontier, to Salonika too high and the existing transit facilities too slow and complex. At the beginning of 1925 the Greek Government therefore reduced the freight rates to about the same level as those in force on the Yugoslav side of the frontier. But when negotiations started in May 1925, the Yugoslavs made much more sweeping claims. They wanted the Greeks not only to enlarge the Salonika Free Zone but also to cede it definitively and without reserve. This would have meant that it would have become virtually Yugoslav territory. The Yugoslavs also asked that they should themselves administer the Djevdjelija-Salonika railway.

Relations between Greece and Yugoslavia had already been strained by Yugoslavia’s denunciation of the 1913 Greek-Serbian Treaty of Alliance a few months earlier. Now Yugoslavia’s claims on Salonika aroused alarm and indignation in the Greeks, who felt that they were a threat to the whole Greek position in Macedonia. They were unwilling to go beyond the grant of commercial facilities at Salonika and a provision for arbitration in case of dispute. On 1 June 1925 both parties decided to break off the negotiations; and the Greek press accused Yugoslavia of ‘imperialistic designs’.

Early in 1926, however, relations became less strained; and in March, during the League Assembly meeting in Geneva, discussions were resumed between the Greek and Yugoslav delegates. On 17 August a Greek-Yugoslav Treaty and a Technical Convention were signed in Athens. The Convention was designed to last for fifty years. In principle, it extended the area of the Free Zone by 10,000 square metres. Agreement was reached on freight rates and customs facilities. Greece was to remain the owner of the Djevdjelija railway but the Yugoslavs could collaborate in the administration of the line.

However, Pangalos was overthrown and Greece failed to ratify the Treaty and the Convention. Greek fears of Yugoslav

1. Survey of International Affairs 1926, p. 213.

35

![]()

‘imperialism’ revived, and in April 1927 Greece put forward objections to certain parts of the Convention. On 25 August 1926 the Greek Parliament decided against ratification. [1]

It was not until Venezelos returned to power in 1928 that a fresh start could be made on improving relations. Then agreement was reached fairly rapidly; six Protocols on the Yugoslav Free Zone in Salonika were signed on 17 March 1929, and a Pact of Friendship, Conciliation, and Judicial Settlement was concluded ten days later. [2] The Yugoslavs, however, continued to make relatively little use of the Free Zone except for exports from the Trepca Mines; and they appeared to remain discontented.

In March 1941, when Hitler was completing his plans for the German invasion of Greece, he tried to bribe Yugoslavia by offering Salonika to the Tsvetković Government. But two days later, on 27 March, came the Yugoslav coup d’état. Tsvetković was overthrown and replaced by General Simović, who failed to denounce the Tripartite Pact but was regarded with such suspicion by the Germans that they decided to invade Yugoslavia. General Simović, in a broadcast from London later that year, claimed credit for refusing to be tempted by the promise of Salonika. [3]

It was thus possible for the Greek and Yugoslav Governments in exile to sign a fresh treaty, in January 1942, in the presence of Mr Eden. This treaty, however, aroused small enthusiasm in either country; and the Yugoslav war-time revolution under Marshal Tito made it a dead letter. The advent of Communists in power in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria in 1944 once again made the Greeks intensely apprehensive of Slav designs on Salonika.

4. THE INTERNAL MACEDONIAN REVOLUTIONARY ORGANIZATION

The only important revolutionary organization in Macedonia between the two wars was, as before, I.M.R.O. But I.M.R.O., once its struggle against the Turks was over and its main effort was directed against the Yugoslavs, quickly degenerated. It

1. Survey of International Affairs 1926, p. 167 ff.

2. Survey of International Affairs 1930, p. 148.

3. C. M. Woodhouse, The Apple of Discord (London, Hutchinson, 1948), p. 21.

36

![]()

ceased to be genuinely revolutionary. In the nineteen-twenties it became more of a financial racket, selling its services to the highest bidder—the Bulgarian Government, the Italians, possibly for a brief period Soviet Russia. It also became an extortion racket, forcing the Macedonian emigrants in Bulgaria and the inhabitants of the Petrich Department (Bulgarian Macedonia) to buy immunity from economic blackmail and terrorization at a heavy price, through ‘voluntary’ patriotic subscriptions on ‘taxes’. It also had its own considerable financial interests in the Petrich Department; the whole economic life of the area was in its hands. In the early nineteen-thirties it trafficked illegally in drugs: the League of Nations Opium Advisory Committee at one time reported that there were ten factories in the Petrich Department and Sofia manufacturing acetic anhydride. [1] When I.M.R.O. was formally suppressed in 1934, its property was estimated at 400 million leva. [2]

The chief basis of its existence was the "large number of Macedonian emigrants in Bulgaria, estimated at well over half a million by Bulgarian propagandists, but probably in reality little over 100,000. Some had fled to Bulgaria from Macedonia to escape from Turkish oppression, some had left at the time of the Balkan Wars, the rest were the emigrants who left Greece under the 1919 Convention. While a few intellectuals made brilliant careers in Bulgaria in politics, business, or journalism, many were peasants who had hated being uprooted from their original homes and who were not easily assimilated in Bulgaria. The upheaval in their lives had often left them thriftless and discontented and turbulent, and they were not particularly popular with the ordinary Bulgarian. So they provided a reservoir of man-power on which I.M.R.O. could draw for its terrorist cadres and its unofficial militia; and, since they had lost their roots, they could easily be browbeaten into obedience to I.M.R.O.

In so far as I.M.R.O. retained its revolutionary aims in the inter-war period, it no longer used its earlier methods of political and military organization and education among the ‘unliberated’ Macedonian population. At best, in the early nineteen-twenties it organized armed raids by small bands mainly in Yugoslav Macedonia. But, as it lost more and more support among the

1. Swire, Bulgarian Conspiracy, p. 50.

2. ibid. p. 287. At that date there were 405-435 leva to the £ sterling.

37

![]()

population in the areas in which it wished to operate, it turned more and more to terrorist acts, assassinations, and bomb outrages. Its political strategy, in so far as it had one, was to keep Macedonia in such a state of unrest that news of it constantly appeared in the world press. By this means it presumably hoped that the great Powers would eventually be convinced that unless they re-drew the Balkan frontiers, Macedonia would be the starting-point for a fresh war.

It is true that the obvious legitimate channel for any Macedonian complaint, through the League of Nations, was blocked by Yugoslavia’s refusal to admit the existence of a ‘Bulgarian’ or ‘Macedonian’ minority. But such appeals, even if heard, could never have been of profit to I.M.R.O.: if, through League of Nations intervention, the demands of the Macedonians of Yugoslavia and Greece had been satisfied, I.M.R.O. would have lost its reason for existence.

I.M.R.O.’s degeneration was above all due to the fact that though it was efficiently organized it lacked, in the inter-war period, any clear-cut political aims and had no serious economic or social ideas other than the catch-phrases of Macedonian revolution and liberation. So it had no very solid appeal to the Macedonian population; and it easily slipped into serving merely as a semi-official branch of the Bulgarian secret police. Above all, it suffered from a fatal ambiguity over the question whether it was aiming at Macedonian autonomy or at annexation to Bulgaria. All these factors facilitated its internal divisions and its self-destruction by gang warfare between rival groups. Its last leader, Ivan Mihailov, was in fact a killer and a gangster on a large scale, not a revolutionary.

These internal weaknesses meant that I.M.R.O., from 1918, or perhaps from 19x3, till 1934, derived its strength far less from its own resources than from its outside backers. First, it was useful to Italy, who wished to prevent the consolidation of Yugoslavia; second, it was useful to King Boris of Bulgaria, who had a strong dynastic interest in preventing a South Slav union which would either have swept away both the Yugoslav and Bulgarian royal houses, or, less probably, would have left the Yugoslav King as the sole survivor. Finally, given the bitter internal feuds and divisions of Bulgarian political life, it was easy for I.M.R.O. to find support in one or other political party or pressure group. So

38

![]()

I.M.R.O. was able to wield power quite disproportionate to its own real strength.

I.M.R.O. emerged from the First World War in a more or less disorganized condition, as a result of the partition of Macedonia in 1912-13 and of the later Bulgarian occupation of Macedonia. It had, however, a more or less undisputed leader in Todor Alexandrov. He was then thirty-eight years old, and had been a member of I.M.R.O.’s Central Committee since his youth. Associated with him in its leadership was the much older General Alexander Protogerov. Both had served in the Bulgarian Army in the occupation of Serbian Macedonia, and were regarded by the Yugoslavs as war criminals. Both, according to one account,1 had been present at an important meeting between the German Kaiser and King Ferdinand of Bulgaria at Nish during the First World War. They thus had close ties with the Bulgarian army and monarchy. The third of the leading members of I.M.R.O. at this period was Peter Chaoulev, another veteran revolutionary who had been Police Commandant of Ochrid during the 1915-18 Bulgarian occupation.

For six years after the end of the war, these three men stuck together, fighting their political enemies inside Bulgaria and their rivals in the Macedonian revolutionary movement, and organizing armed raids inside Yugoslav Macedonia.

On the first of these three fronts they won a decisive success in 1923, when together with the Bulgarian Officers’ League and the politician Tsankov, they succeeded in overthrowing the Agrarian regime and killing its leader Stambulisky. Although Stambulisky’s successor, Tsankov, pursued a half-hearted policy of reconciliation with Yugoslavia, in practice he left I.M.R.O. a fairly free hand inside Bulgaria. And I.M.R.O. was able to consolidate its administrative and economic grip on the Petrich Department, which became the territorial basis of its power.

On the second front, against rival Macedonian groups, I.M.R.O. was at first less successful. The most important of these was the Federalist group, which genuinely aimed at creating an autonomous Macedonia within a South Slav Federation. The Federalists thus represented the more truly ‘Macedonian’ tradition of the earlier I.M.R.O., in contrast with the ‘Supremist’ trend of the Alexandrov-Protogerov group. The leading members

1. Stoyan Christowe, Heroes and Assassins (London, Gollancz, 1935), p. 126.

39

![]()

of the Federalists, who formed their own organization in 1921, were Philip Athanasov and Todor Panitza, both old I.M.R.O. men. Neither of them had ties with the Communists, though their Macedonian programme was not far removed from that of the Communists in the nineteen-twenties.

Another prominent Macedonian who soon came to be associated both with the Federalists and the Communists was Dimiter Vlahov. Pie also was a veteran member of I.M.R.O. In 1908 he, together with Panitza, Hadji Dimov, and other more noted Macedonian revolutionaries, had joined in forming a ‘Popular Federal Party’, which advocated the use of the Macedonian Slav dialect in schools, to contest the Turkish elections. During the First World War, however, Vlahov had served as District Governor of Prishtina under the Bulgarian occupation. In the first years after the war he seems to have maintained his ties with I.M.R.O.; but by 1924, as Bulgarian Consul-General in Vienna, he had formed close contacts with Soviet representatives there; and from this time on, if not also earlier, he worked with the Communists. It is not, however, clear at what point he actually joined the Communist Party.

Hadji Dimov, another representative of the Federalist trend within the earlier I.M.R.O., became a Communist soon after the end of the First World War. There was, therefore, a definite tendency towards Communism within the Federalist group; and this led to internal divisions and finally, after 1925, to an open split.

Meanwhile, in the early nineteen-twenties, the Federalists had some success in organizing small armed bands in Yugoslav Macedonia, to operate both against the Yugoslav authorities and where necessary against the bands of Alexandrov’s I.M.R.O. They were thus at this period the hated rivals of the Alexandrov-Protogerov-Chaoulev group. But in 1924 there was a startling development: a momentary reconciliation between I.M.R.O., Federalists, and Communists, and the formation of a short-lived common Macedonian front against all the three Balkan Governments, including the Bulgarian, which had partitioned Macedonia.

It is not quite clear at what point the flirtation between I.M.R.O. and the Federalists, and the Comintern began. The I.M.R.O. newspaper, Freedom or Death, writing long after the

40

![]()

event in 1927, said that the I.M.R.O. leader, Alexandrov, had, in August 1923, sent Dimiter Vlahov to Moscow, where Athanasov, the Federalist, had already arrived. According to this account, Moscow was conciliatory in its attitude towards Alexandrov, but at the same time urged him to unite with the Federalists. [1]

Whatever the truth of this story, it seems clear that the third member of the I.M.R.O. triumvirate, Peter Chaoulev, who spent much of his time abroad on I.M.R.O.’s business, had at about the same time made contacts with Communist representatives; and he may well have acted as intermediary.

However the first contacts may have been made, early in 1924 I.M.R.O. received a definite incentive to seek outside support in a fresh quarter. This was the Italian-Yugoslav Pact of Friendship, which meant at least a temporary decrease in Italian backing for I.M.R.O. Also, there may have been certain differences of opinion within the higher cadres of I.M.R.O. about the degree of I.M.R.O.’s dependence on the Bulgarian War Office.

Whatever their complex motives may have been, Alexandrov and Protogerov went to Vienna in March 1924. There they conferred with their associate, Chaoulev, who proceeded to negotiate with Vlahov, Athanasov, and Panitsa, and probably also with authorized Comintern representatives.

The result of the Vienna negotiations was that at the end of April or in early May agreement was reached on the creation of a common Macedonian Revolutionary Organization combining all groups, and on a declaration of I.M.R.O.’s ‘new orientation’. This declaration had a strongly Communist flavour. It attacked not only the Yugoslav and Greek Governments as oppressors of the Macedonians, but also the Bulgarian Government, which it accused of secret negotiations with Yugoslavia aiming at I.M.R.O.’s destruction. (For a fuller account of this document, see below, pp. 54-7.)

Alexandrov, according to one version, [2] authorized his associates Protogerov and Chaoulev to sign the agreement on his behalf, while he himself left for a tour of western Europe. A pro-I.M.R.O. account [3] says merely that ‘it is difficult to say whether Alexandrov authorized his signature or not’. In any case, publication of the

1. Swire, Bulgarian Conspiracy, p. 184.

2. ibid. p. 185.

3. Christowe, Heroes and Assassins, p. 178.

41

![]()

declaration was withheld until July, after Alexandrov had returned to Sofia. It then appeared, possibly against Alexandrov’s wishes, in the first issue of Dimiter Vlahov’s new Vienna publication, Fédération Balcanique, which appeared on 15 July 1924.

The declaration, as published, bore the signatures of Alexandrov, Protogerov, and Chaoulev. Its appearance must inevitably have precipitated a crisis in relations between the I.M.R.O. leaders and the Bulgarian War Office, their traditional supporters. Probably Alexandrov and Protogerov received a stern warning, particularly from the War Minister, Volkov. In any case, they repudiated their signatures and declared that Vlahov and Chaoulev, who were still in Vienna, had acted without their authority.

That was the end of the flirtation between I.M.R.O. and the Federalists and Communists. An I.M.R.O. assassin killed Chaoulev in Milan at the end of 1924. Vlahov broke with Athana- sov, who did not stand as far to the left; he stayed on in Vienna and formed a new ‘United I.M.R.O.’, advocating an autonomous Macedonia within a Federation of Balkan Socialist Republics (which was in fact the Comintern policy of this period). He continued to publish Fédération Balcanique to preach this aim and to flay the old I.M.R.O. His semi-Communist ‘United I.M.R.O.’ never seems, however, to have had any very large following in Macedonia itself. Probably in 1936, Vlahov went to live in Moscow. He re-emerged in 1943 as a prominent member of Marshal Tito’s new regime in Yugoslavia.

I.M.R.O., meanwhile, returned to a closer alliance with the Bulgarian War Office than ever before. But it was rent by grave internal division. On 31 August 1924, the eve of I.M.R.O.’s first post-war congress, Alexandrov was murdered in the mountains of Bulgarian Macedonia. Three versions of the murder have been put forward: first, that it was instigated by the Communists and/or Federalists, in revenge for his repudiation of the Vienna Declaration; next (the version put out four years later by Ivan Mihailov), that his colleague Protogerov was responsible; finally, that Mihailov himself was responsible. According to this last version, Mihailov must have been instigated by the Bulgarian War Office, which could no longer trust Alexandrov after his flirtation with the Communists.

Whatever the true explanation, the murder gave I.M.R.O. the chance to assassinate a number of Federalists and Communists,

42

![]()

including Hadji Dimov and Panitza. Panitza was dramatically shot during a performance of Peer Gynt at the Vienna Opera, on 8 May 1925, by the girl who afterwards became Ivan Mihailov’s wife.

Protogerov succeeded Alexandrov as leader of I.M.R.O.; but the young Ivan Mihailov became a member of the I.M.R.O. Central Committee, and rapidly came to have more and more power in the Organization. His influence brought about the final degeneration of I.M.R.O. into a gangster organization.

During the four years that Protogerov and Mihailov nominally worked together, their association can never have been easy. Protogerov, with something of a military career behind him, and a reputation as a kindly if weak-willed man, was a very different type from the young, completely ruthless and completely unscrupulous Mihailov. However, Mihailov allowed Protogerov to survive until he had consolidated his own grip on I.M.R.O. He was helped by the replacement of the Tsankov Government by that of the Macedonian, Liapchev, who was remarkably tolerant of I.M.R.O. Mihailov also established close personal ties with Fascist Italy, whose interest in I.M.R.O. had now revived.

Thus by 1928 Mihailov was ready to grasp sole power. On 7 July Protogerov was shot dead in a Sofia street. The first rumour that went round was that he was the ‘victim of Italian imperialism’, because he had rejected a proposal by Mussolini for an Italian protectorate over Macedonia. But almost immediately three leading members of I.M.R.O. formed a pro-Protogerov group and publicly charged Mihailov with Protogerov’s murder. On 21 July Mihailov himself issued a communique stating that Protogerov’s assassination was an ‘execution’ ordered in conformity with the directive of the last I.M.R.O. Congress to punish all concerned in the murder of Alexandrov in 1924.

On 22 July the I.M.R.O. Congress met, without the pro- Protogerov group, and approved Mihailov’s conduct of I.M.R.O.’s affairs. Mihailov was appointed to a new Central Committee from which the ‘Protogerovists’ were excluded. The ‘Mihailovists’ at once began assassinations of Protogerovists.

It was at this moment that Britain and France made their unsuccessful démarche, urging the Liapchev Government in effect to liquidate I.M.R.O. At one point in the prolonged cabinet crisis which followed, the Government promised to make drastic

43

![]()

changes in the administration of the Petrich Department (Bulgarian Macedonia). But in practice nothing effective was done, and Liapchev and Volkov, with King Boris’s blessing, retained power.

As the Protogerovists began to fight back against the Mihai- lovists, gang warfare broke out between the two groups in the streets of Sofia and elsewhere in Bulgaria. Assassinations in broad daylight became frequent. Although this fratricidal war destroyed what remained of I.M.R.O.’s prestige as a genuine revolutionary movement, the Mihailovist I.M.R.O. remained very powerful inside Bulgaria, protected by the authorities and ultimately by the King. The Protogerovists received no such protection and sought allies among the surviving Federalists, the Bulgarian Agrarian exiles in Belgrade, and ultimately the Yugoslavs.

So things went on until 1933 when King Alexander made his first conciliatory gesture towards King Boris, which made the atmosphere less favourable for I.M.R.O. But King Boris was not yet prepared to abandon I.M.R.O. The blow came in May 1934. Following the Military League Zveno coup, I.M.R.O. was suppressed, leaving remarkably little trace inside Bulgaria. Many of its members fled abroad—Mihailov to Turkey, others to the Croat Ustashi in Italy, others to terrorists’ camps in Hungary such as Janka Puszta. It was from these bases that the murder of King Alexander by one of I.M.R.O.’s most skilful assassins, Chernozemski, was organized in October 1934. After that little was heard of I.M.R.O.; the Macedonian revolutionary movement—terrorist, Federalist, or Communist—was quiescent until war broke out again in the Balkans.

In 1941 the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia theoretically opened up fresh opportunities for I.M.R.O. There seems, however, no definite evidence that former members of I.M.R.O. were employed by the Bulgarian occupation authorities in Yugoslav Macedonia. It was frequently rumoured that Ivan Mihailov was in Zagreb, where his old associate, Ante Pavelić, was now in power in the puppet ‘Independent State of Croatia’. According to a story current in Yugoslav Communist circles, Hitler held him in reserve as possible Gauleiter of an Independent Macedonia, should the Bulgarian occupation authorities fail to hold Yugoslav Macedonia. By this account, Mihailov was actually

44

![]()

sent by plane to Skoplje in the final phase of the war, but was forced by the Yugoslav Macedonian partisans to depart without setting foot on Macedonian soil. This story is, however, not substantiated.

Whether or not Mihailov outlived the war is still a mystery. But it seems clear that only the most scattered relics of I.M.R.O. can have survived the events of the fifteen years since 1934.

The quick collapse and disintegration of I.M.R.O. are perhaps to be explained by four factors. First, it would never come into the open over the question whether it really wanted Bulgarian annexation or Macedonian autonomy, and so created confusion and division among its followers. Secondly, after the First World War it had no constructive ideas of its own apart from the forcible overthrow of the existing political order in Macedonia. Thirdly, it failed to organize widespread popular support in Yugoslav Macedonia, its chief target, and relied increasingly on isolated terrorist action; once the terrorist cadres were broken up, little was left of the Organization. Fourthly, after the First World War I.M.R.O. relied far too heavily on outside support, especially from Fascist Italy; when this support was withdrawn or weakened, I.M.R.O. no longer had sufficient internal resources to make good the loss.

The collapse of I.M.R.O. in the nineteen-thirties left a vacuum which the Communists, who in the early nineteen-twenties had hoped to gain control of the Macedonian revolutionary movement, were surprisingly slow to fill.

5. THE COMMUNISTS AND MACEDONIA

The Bolshevik leaders, some years before the Russian Revolution, had taken an interest in the Balkans and Macedonia, partly, perhaps, because the region was a favourite target of Tsarist foreign policy, partly, no doubt, because of its revolutionary possibilities. Trotsky was a war correspondent in the Balkan wars. [1] Lenin at the same period wrote an article on ‘the Social Significance of the Serb-Bulgarian Victories’. Lenin said that these victories meant the undermining of feudalism in Macedonia

1. Leon Trotsky, Ma Vie (Paris, Reider, 1929), pp. 77-9. Characteristically, Trotsky denounced Bulgarian atrocities against wounded Turks and condemned the ‘Conspiracy of Silence’ in the Russian press on this subject.

45

![]()

and the creation of a more or less free class of peasants, and guaranteed the whole social development of the Balkan lands. [1]

Another Russian who in the pre-revolutionary era counted himself an expert on the Macedonian question, and who was later associated with the Bolsheviks, was Professor Nikolai Derzhavin, of Petrograd University. His book, Bulgaro-Serb Relations and the Macedonian Question, which appeared during the First World War, took a strongly pro-Bulgarian line on the Macedonian issue, and called on the Serbs, who were then fighting with the Russians, to modify the results of the Balkan Wars. (The book was in fact reprinted in Leipzig under the auspices of the Royal Bulgarian Consul.) Derzhavin claimed that a new day was dawning in the life of the Slavs; and his peroration was:

May this great historic moment of the triumph of right and justice banish from the lives of our brothers of the South those accidental barriers which have made irreconcilable enemies of two brother peoples, rupturing their good neighbourly relations and breeding hatred. May the heroic Serb people at last find the necessary moral force—and they have it, it dwells within them—to recognize spontaneously what has long and unanimously been recognized by history, science, and the national sentiment of the Macedonian population itself, which sees in the Bulgarians its brothers in language and blood, and which has fought hand in hand with them for religion, life, and liberty. And recognizing this truth, may the Serb people, with as much courage as they are showing in their fight alongside the Russian people against the enemy of Slavism, face the solution of this grandiose Slav problem, which is being decided in this moment, and for which the best sons of the generous Russian people are shedding their precious blood with so much abnegation, in the name of the liberty and happiness of all the Slavs. [2]

The phrasing, if not the substance, of the closing passage is of course strongly reminiscent of some Soviet propaganda during the Second World War. That is perhaps not surprising: Derzhavin represented a type of semi-romantic pan-Slavism which, although it fell from favour after the Russian Revolution, was revived forcefully when Russia was drawn into the war in 1941. At this point also Derzhavin himself reappeared on the scene at the war-time All-Slav Congresses held in Moscow.

1. Lazar Mojsov, The Bulgarian Workers’ Party (Communist) and the Macedonian National Question (Belgrade, Borba, 1948).

2. N. S. Derzhavin, Bulgaro-Serb Relations and the Macedonian Question (Lausanne, Librairie Centrale des Nationality, 1918).

46

![]()

In the first years following the Russian revolution the Bolshevik leaders, whatever may then have been their attitude to Derzhavin’s pan-Slavism, seem, like him, to have tended towards a pro-Bulgarian attitude.

When the Communist Parties of Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Greece were formed shortly after the end of the First World War, the Bulgarian Party had the most solid foundations. It evolved in 1919 from the ‘Narrow’ wing of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party, which already had considerable organizational experience and had such energetic and forceful leaders as Vasil Kolarov and Georgi Dimitrov. Perhaps for that reason, perhaps also because it had Soviet backing, it always took the lead among the Balkan Communist Parties, particularly over the Macedonian question.

The Yugoslav Communist Party was handicapped from the start by the complexities of Yugoslavia’s nationalities problem, which produced organizational weaknesses within the Party and which brought down upon it stiff rebukes from the Comintern and from Stalin himself. The Greek Communist Party was by far the smallest of the three; its chief strongholds were in the north of Greece; but, from its early days, it found the Macedonian problem a millstone round its neck. Whatever its policy of the moment, it was always suspected of plotting to cede Greek Macedonia to the Slavs.

Early in 1920 the Bulgarian and Yugoslav Communist Parties each claimed to have 30,000 members. The Greek Communist Party, which bore the name of the ‘Socialist Workers’ Party’, only claimed 1,300 members. [1] It had sections in several Macedonian centres, including Salonika, Seres, Kavalla, and Drama.

Each of the three Balkan Communist Parties was organized on the territorial basis of the three Balkan States as they emerged from the First World War (or the Balkan Wars). There was at this time no trace of any separate Macedonian Communist organization. In June 1920 a Macedonian, of Skoplje, called Dasan Cekić was one of the signatories of a manifesto issued by the Central Party Council of the Yugoslav Communist Party. The manifesto took a fairly centralist line on the nationalities problem; the Party’s attitude then was that the outside world was exaggerating the national differences within Yugoslavia; in reality the

1. Kommunismus (periodical journal, Vienna), 27 March 1920.

47

![]()

only struggle was between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. [1]

In this early stage, the Communist Parties in general kept to such innocuous slogans as ‘The Balkans for the Balkan Peoples’, without probing deeply into specific problems. The Bulgarians, however, showed an eager interest in promoting Balkan solidarity. In January 1920 the Bulgarian, Yugoslav, and Greek Communist Parties all sent delegates to Sofia, on Bulgarian initiative, to form the ‘Balkan Communist Federation’. This was a group which during the nineteen-twenties under Bulgarian leadership came to have a certain standing in the Communist world: decisions taken at its periodic meetings (usually in Sofia) were sometimes formally endorsed and supported by the Comintern.

The Comintern, in those early years, seems to have had somewhat hazy ideas about the Macedonian question. Zinoviev, as President of the Executive Committee of the Comintern, sent a message of greeting to the Communist Parties of Bulgaria, Roumania, Serbia, and Turkey, early in 1920, which was rather a muddled document. It was sent in preparation for the Second Congress of the Third International, and tried with doubtful success to make the best, or worst, of all worlds. Zinoviev said:

While the Paris Supreme Council has abandoned to the Serbian military clique, the Roumanian big landowner class, and the corrupt Roumanian bureaucracy, millions of foreigners—Bulgarians, Albanians, Germans, Ukrainians, and Russians—for them to devour, it has given the five great Powers the right, if needful, to use the national minorities as a means of exercising pressure on Serbia, Roumania, and Greece, with the aim of obtaining every kind of economic and political advantage. . .

The capitalists of France and England . . . will not be in a position to help the Balkan countries. On the contrary, they will in future exploit these countries still more fully as sources of raw materials and as markets for unnecessary goods. . .

The new national divisions, created after the defeat of Austria-Hungary and the disruption of Bulgaria and Turkey, have intensified the nationalities problem to an extent greater even than before the war. Many more elements of foreign nationality have come under the rule of the victors. And the policy of national oppression, of insatiable militarism, gives rise to a yet more powerful drive towards freedom. And the struggle for freedom takes on a yet wider scope.

Against the rule of the Serbian bureaucratic and landowning oligarchy, there are rising up the Macedonian Bulgarians, the Albanians, the Montenegrins, the Croats, and the Bosnians. . . Against the

1. Kommunismus, 1920.

48

![]()

rule of the Greek trading, speculating, and profiteering bourgeoisie are fighting the Albanians of Epirus and the Turkish and Bulgarian peasants of Thrace.

A new period of embittered nationalist agitation, national hate, and national-bourgeois wars threatens the Balkan and Danube peoples. Only the Proletariat can, through its victory, avert a new catastrophe... Only the victory of the proletarian dictatorship can unite all the masses of the peoples in a Federation of Socialist Balkan (or Balkan and Danube) Soviet Republics, and save them both from landowning- capitalist exploitation by their own and by the foreign bourgeoisie, and also from colonial enslavement and national disputes. The Communist Party is called by existing circumstances to play an even bigger role in the Balkan Peninsula than in capitalist countries where there are no nationalities problems. . .

In the present phase of preparation for the Socialist Revolution, the Balkan Communist Parties must, parallel with their work inside their own countries, pay the greatest attention to a firm association and co-ordination of the activities of the individual Balkan Parties. Victory is impossible without the closest mutual association of all the Balkan Parties. [1]

Zinoviev’s message provided the ideological framework for Communist handling of the Macedonian question in the early nineteen-twenties. It did not, however, as yet make any attempt to define the question. But it is of interest that Zinoviev referred specifically to ‘Macedonian Bulgarians’ in Yugoslavia, and that, perhaps by chance, he omitted any reference to ‘Macedonian Bulgarians’ in Greece. Whether this vagueness was due to ignorance or design is not clear; but it is clear enough that the Comintern quickly took note of the revolutionary possibilities of the various nationalities and minorities problems of the Balkans, and hoped to exploit them to undermine the new ‘bourgeois’ Balkan Governments and to weaken the position of the western Powers in Balkan affairs.

The Comintern’s attention was attracted to the Macedonian question, as such, by the influx of Greek refugees into Greek Macedonia and Thrace during and after the Greek-Turkish War. The Fourth Comintern Congress in 1922 decided to campaign against the refugee movement. The refugees, it said, must be convinced that they were the victims of Greek imperialism, and their settlement in Macedonia and Thrace was to be regarded as a capitalist attempt to destroy the ethnological character of the two regions.

1. Kommunismus, 5 March 1920.

49

![]()

This question was again taken up at the meeting of the Balkan Communist Federation held in 1924. [1] It directed the Greek Communist Party to fight ‘most bitterly’ against the attempt to hellenize the new territories by the expulsion of Turks and Bulgarians. The Greeks were asked to agitate for the annulment of the Greek-Turkish Convention for the exchange of populations, and also for the non-fulfilment of the Greek-Bulgarian Convention. (On this last point the Communist directive coincided with the I.M.R.O. directive). The Greek Communist Party was told that its slogan must be the self-determination of the minorities.

The Greek Communist Party Central Committee raised objections to this directive, and was presumably reproved by the Comintern. At the Fifth Comintern Congress, in 1924, the Greek delegate, Maximos, said that his Party opposed the Greek-Turkish population exchange but added: ‘the fact remains that there are 700,000 Greek refugees in Macedonia’. (See also below, pp. 61-2.)

The question of Macedonian autonomy, as such, first seems to have been raised formally in the Communist world at the Balkan Communist Federation conference in 1922. Vasil Kolarov, the Bulgarian, presided and called for discussion of the question. The Greek Communist Party representative, however, asked that discussion should be deferred until he had consulted the Greek Communist Party Central Committee.

In the following year, 1923, internal upheavals in Bulgaria put Macedonian autonomy temporarily in the background, though they had their Macedonian repercussions. In June came the overthrow of Stambulisky and the Agrarian regime by the Officers’ League, Tsankov, and I.M.R.O.; the Bulgarian Communist Party remained neutral and failed to support the Agrarians. For this failure it was strongly criticized, after the event, by Moscow; the exiled Hungarian Communist, Matyas Rakosi, wrote a scathing article pointing out the Bulgarian Party’s errors. [2]

The Comintern was also seriously worried at the part played by the Macedonians in the June coup. The Enlarged Executive of the Comintern declared in a special manifesto on Bulgaria [3]:

1. International Press Correspondence (Communist periodical issued in English and other languages, hereinafter referred to as I.P.C.), 1 May 1924.

2. I.P.C., 26 July 1923.

2. ibid., 23 July 1923.

50

![]()

Peasants of Macedonia! Revolutionaries of Macedonia! You have allowed the Bulgarian counter-revolution to use you for the coup d’état, although your interests, as shown by your past, are most closely interwoven with the interests of the working people, with the interests of the revolution in the Balkans and throughout the world. The Stambulisky Government delivered Macedonia to the Serbian bourgeoisie in order to gain their support. It persecuted you in bloody fashion. But do not believe for a moment that the counter-revolutionary movement will be able to liberate the Macedonian people . . . Only a Workers’ and Peasants’ Government in Bulgaria . . . will blaze the path for the establishment of a Balkan Federation of Workers’ and Peasants’ Governments, which alone can bring about your deliverance . . . For the sake of your own national freedom, you must join hands with the Bulgarian Workers and Peasants.

This appears to have been the Comintern’s first, still somewhat imprecise, formulation of its views on the Macedonian problem. Its appeal to the Macedonians to join hands with the Bulgarian Communists (without mention of the Yugoslav or Greek Communists), may betray a fundamental pro-Bulgarian bias; more probably, it sprang from the Comintern’s conviction that Bulgaria, alone of the Balkan countries, was then ripe for revolution. Presumably plans were already in existence for the September Communist insurrection in Bulgaria, and the Comintern hoped to enlist Macedonian support for it.

The Comintern appears to have had some grounds for this hope. According to one source, [1] negotiations had already started in the Spring of 1923 between the representatives of Alexandrov, the I.M.R.O. leader, and Vasil Kolarov and other Bulgarian Communists. Aleko, the local I.M.R.O. chief in the Petrich Department, favoured co-operation with the Communists. The negotiations were interrupted by the overthrow of Stambulisky in June, but were resumed in July 1923. And according to the same account, Alexandrov probably sent Dimiter Vlahov to Moscow in August. [2]

But these negotiations—assuming that they took place—must have been abortive. I.M.R.O. bands helped Tsankov and Volkov to suppress the September rising, and were denounced for it in the Communist press. The Bulgarian Communists in exile launched a violent propaganda campaign, which lasted for many months, against the Tsankov regime. But the Comintern’s

1. Swire, Bulgarian Conspiracy, p. 183.

2. ibid. p. 184.

51

![]()

attempt to drive a wedge between Tsankov and I.M.R.O. continued.

In March 1924 the Balkan Communist Federation, at its sixth congress, came into the open with a detailed Macedonian programme. It spoke flatteringly of the old I.M.R.O.; and it called for the setting up of a Republic of Macedonia within a ‘voluntary Union of Independent Balkan Republics’. Some passages of this long document1 are worth quoting fully:

The possession of Macedonia, by reason of the geographical position of the country, assures domination over the whole Balkan peninsula. That is why the country always roused the cupidity of the interested imperialist States, as well as of the neighbouring Balkan States. The varied ethnographical composition of its population has always served as a pretext for the interference of outsiders. All the nationalities which dominate in the neighbouring States are represented in Macedonia, but in such proportions that not one of them attains an absolute majority. Consequently the domination of any one of the Balkan States over Macedonia means national oppression of the majority of the Macedonian population and stirs up national struggles which are exploited by the other interested States for their schemes of conquest. . . The Serbian and Greek hegemony over this country, which was divided between them after the Balkan war, signifies national oppression for the majority of the population. . .

The Macedonian population has for years carried on a heroic and bitter struggle for national freedom. The rivalries stirred up by the bourgeoisie of the neighbouring States and the hatred between the various Macedonian nationalities have often led to mutually destructive wars ... but have never been able to destroy the conviction among the Macedonian slaves [sic] that only an autonomous and united Macedonia could assure right and liberty to all its nationalities.

The Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, the real organizer and leader of the revolutionary struggle of the Macedonian slaves, regardless of nationality, is working to strengthen this conviction. . .

A united and autonomous Macedonia is now the slogan of the Macedonians in all corners of their Fatherland, which is covered with ruins. It is under this slogan that they are organizing and conducting the struggle.

The duped Bulgarian bourgeoisie, which has only received the very least share of the spoils of Macedonia, is trying afresh to take advantage of the Macedonian revolutionary movement, and to take it under its control. But in spite of all the efforts of its agents among the Macedonian revolutionary organizations, it has not succeeded in winning the sympathies of the working masses of the Macedonian regions, and causing them to deviate from an ‘independent struggle’. The Macedonian

1. I.P.C., 10 April 1924.

52

![]()

people have been so severely tried in the past that they no longer have any desire to submit to the influence of their ‘friends’ and ‘patrons’ either near or far. . .

A section of the Macedonian emigrants has been made use of by the Bulgarian counter-revolutionary movement, to repress the revolt of the Bulgarian workers and peasants. The conduct of the duped Macedonians, who, in the guise of Macedonian revolutionaries, became the mercenaries of the Bulgarian bourgeoisie and the executioners of the Bulgarian working people, is a deliberate attack against the very cause of Macedonian liberation itself. The Macedonian workers must emphatically condemn this attack. . .

The bourgeoisie of the Balkan countries knows of no other method for the solution of the Macedonian and Thracian problems than pillage, terror, exile, and violent denationalization. This was the method of the Bulgarian nationalists, while they were masters in Macedonia and Thrace. The Serbian and Greek bourgeoisie follow precisely the same way. The Serbian bourgeoisie maintains in Macedonia a cruel terrorist regime, destroys or forces into exile the conscious part of the Bulgarian, Turkish, and Albanian population and substitutes for it settlers from other parts of Yugoslavia; it oppresses all the non-Serb nationalities, closes their churches and their schools, prohibits their press and suppresses their languages. Every revolt, every protestation of the peoples, reduced to despair, is followed by bloody repression on the part of the Serbian Government. We witness the same spectacle in the other part of Macedonia and Thrace, subject to Greek domination. . .

The Communists do not at all repulse the national Macedonian and Thracian organizations which group the working population around them in the name of their national and cultural interests. On the contrary, they maintain the closest relations with them, exert themselves in their leadership and activity to insure to the working masses a predominant position which is energetically opposed to the big agrarian bourgeois and adventurous elements, which would make use of the organizations to serve their class interests and which are always ready to betray the interests of the great working masses. The tactics of the united front with these organizations and even of the participation of the Communists in the same will render easier this task of the Communist Parties. . .

In setting up the ideal of a workers’ and peasants’ government, the Communist Parties and the Communist Federation of the Balkans declare that the Federative Republic of the Balkans will assure peace, independence, and liberty of development of all the peoples of the Peninsula, that it will be a voluntary union of independent Balkan Republics, including the Republics of Macedonia and Thrace.

A number of conclusions may be drawn from this document. It was obviously drafted by someone who had a good knowledge

53

![]()