Queen of the Highlanders*

Edith Durham in "the land of the living past"

Charles King

TLS, 4 Avgust 2000, pp. 13-14

Edith Durham, it should be said, was a difficult woman. The first entry

for her in Foreign Office files, from 1908, reads "Durham, Miss M.

E., Inadvisability of Corresponding With", Rebecca West, R. W, Seton-Watson,

Henry Wickham Steed, and most other important writers on East European

affairs between the two world wars thought her a woman to be avoided. An

advocate of the national aspirations of the Albanians, she was vilified

by her critics in Britain, who generally looked more favourably on the

cause of Yugoslav unity than she did. Her polemics on Balkan politics and

the retrograde culture of what she called the "Serb vermin" alienated

her contemporaries. Many thought her at best wildly eccentric and at worst

completely mad. Travelling and living among the clansmen of upland Albania,

they said, had taken its toll on her judgment and sense of decorum. "The

fact is that while always denouncing Balkan mentality", wrote Professor

Seton-Watson in 1929, "she is herself exactly what she means by the

word."

Durham

was, however, the twentieth century's indispensable interpreter of Albania,

and arguably the most important writer on that culture since J. C. Hobhouse

journeyed through the Albanian lands with Byron. She was adored among the

Albanians themselves, who knew her as "Kralica e Malësorevet" -

the Queen of the Highlanders. "She gave us her heart and she won the

ear of our mountaineers", the exiled Albanian king, Zog, wrote to The

Times on her death in 1944 (even though she was not on good terms with

him, either). The only other Briton to have been so lionized was, improbably,

Norman Wisdom, whom the Communist dictator Enver Hoxha found uproariously

entertaining. Durham's most famous work. High Albania (1909), is valued

by collectors. It is still the pre-eminent guide to the folk customs, social

structure, customary law, religious beliefs and traditional tales of the

Albanians, especially in the highlands north of the Shkumbin river, where

tribal social organization and the distinctive Gheg dialect once set off

the region's inhabitants from the lowlanders to the south. (In 1998, Peter

Hopkirk's fine first edition sold at Sotheby's for £620.)

Durham

was, however, the twentieth century's indispensable interpreter of Albania,

and arguably the most important writer on that culture since J. C. Hobhouse

journeyed through the Albanian lands with Byron. She was adored among the

Albanians themselves, who knew her as "Kralica e Malësorevet" -

the Queen of the Highlanders. "She gave us her heart and she won the

ear of our mountaineers", the exiled Albanian king, Zog, wrote to The

Times on her death in 1944 (even though she was not on good terms with

him, either). The only other Briton to have been so lionized was, improbably,

Norman Wisdom, whom the Communist dictator Enver Hoxha found uproariously

entertaining. Durham's most famous work. High Albania (1909), is valued

by collectors. It is still the pre-eminent guide to the folk customs, social

structure, customary law, religious beliefs and traditional tales of the

Albanians, especially in the highlands north of the Shkumbin river, where

tribal social organization and the distinctive Gheg dialect once set off

the region's inhabitants from the lowlanders to the south. (In 1998, Peter

Hopkirk's fine first edition sold at Sotheby's for £620.)

Today, Durham is a figure sadly overshadowed by more widely known travellers

and correspondents. Only one of her works is still in print and, even then,

not easily available. Her papers and photographs are divided between the

Museum of Mankind and the Royal Anthropological Institute. Her rich collections

of Balkan jewellery and textiles are kept at the Pitt Rivers Museum in

Oxford and the Bankfield Museum in Halifax, West Yorkshire, where a permanent

exhibition on her life and work was installed in 1996. Two essays in the

outstanding collection Black Lambs and Grey Falcons: Balkan women travellers,

now out in a revised edition edited by John B. Allcock and Antonia Young,

provide introductions to Durham's complex personality and career. But unlike

Freya Stark and other women adventurers in the Near East, she has not yet

found her biographer.

The vehemence of Durham's well-placed detractors is remarkable. Even

today, the cutting tone of their denunciations still shocks. In part, it

was a reaction to Durham's own confrontational personality. Yet there is

more to the Durham question than her personal relationship with other British

intellectuals. The way she was perceived by her contemporaries - and

especially her stormy exchanges with Seton-Watson - reveals something

about how turmoil in the Balkans can infect the personal lives of those

who interpret it and, more broadly, about Western intellectuals and their

position as willing proxies for competing interests abroad.

Mary Edith Durham was born in 1863 in Hanover Square, London. Her father,

Arthur Edward Durham, was a distinguished surgeon who sired a large Victorian

family of eight children, all of whom went on to excel in respectable professions.

Edith manifested artistic ambitions and, after being educated privately

in London, attended the Royal Academy of Arts. She became an accomplished

illustrator and watercolourist, exhibiting widely and contributing detailed

drawings to the amphibia and reptiles volume of the Cambridge Natural

History.

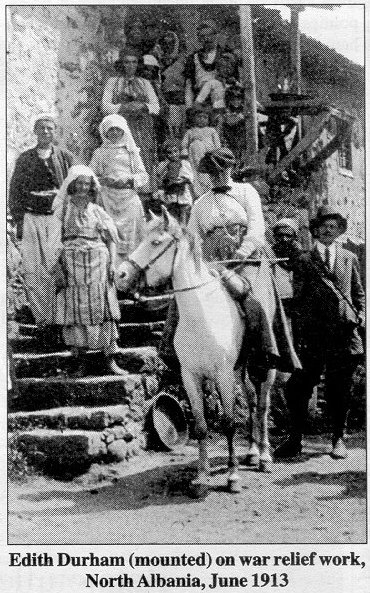

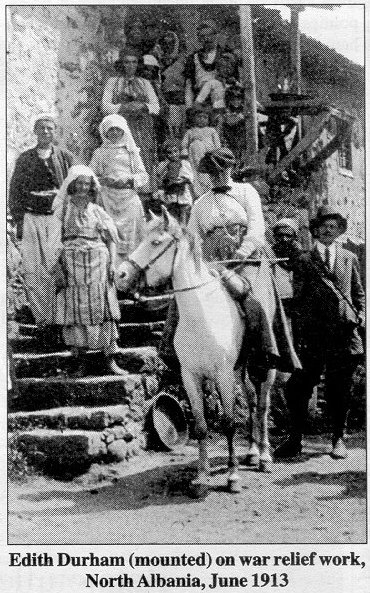

As the eldest child - and still unmarried in her thirties - Edith took

on the task of caring for her ailing mother after her father's death. Filial

responsibility turned out to be the unlikely impetus for her Balkan entanglements.

At thirty-seven, Durham sailed from Trieste down the Dalmatian coast to

Cattaro and trekked overland to Cetinje, the capital of the exotic principality

of Montenegro. The trip was intended as a palliative, recommended by her

doctor after years caring for her mother, but on this journey, she found

her vocation. Over the next twenty years, she travelled frequently in the

south Balkans. working in various relief organizations, capturing scenes

of village life in water-colour, and collecting folklore and folk art.

She also began to write frequently, and during the Balkan wars and the

First World War, became a fervent promoter of the Albanian national cause

in periodicals in Britain, Germany and the United Slates. Over the next

two decades, she wrote seven books on Balkan affairs, beginning with Through

the Lands of the Serb (1904), a beautifully evocative if wide-eyed

account of her first several trips to Montenegro and Serbia, through to

Some Tribal Origins, Laws and Customs of the Balkans (1928), a useful

compendium of now extinct folk beliefs and rituals. She also became a frequent

contributor to the journal Man, and her dispatches and learned articles

on Balkan folklore earned her a place as Fellow of the Royal Anthropological

Institute.

Durham called the Balkans "the land of the living past". For her, the

region was not an alien, Oriental domain but rather a kind of mirror in

which Western visitors might see themselves at a much earlier stage of

development. As she wrote in High Albania, "For folk in such

lands time has almost stood still. The wanderer from the West stands awestruck

amongst them, filled with vague memories of the cradle of his race, saying,

"This did I do some thousands of years ago; thus did I lie in wait for

mine enemy; so thought I and so acted I in the beginning of Time.'"

As for previous generations who journeyed south and east, the Balkans were

for Durham a proto-Europe, a place where the past was prologue and every

village bard a vestigial Homer. Geography, as it were, recapitulated phylogeny.

There is a professional hazard to studying other countries and peoples.

No one who travels to faraway lands, managing to learn the language and

something of the local culture, can be completely immune to the romantic

thrill of being seen by the natives as their intercessor and interpreter

to the outside world. Such was Durham's relationship to the Albanians.

She came to see their plight - a nation whose territorial aspirations went

largely unheeded after the First World War - as unique among the nested

grievances in the Balkans. She had been well received in the Albanian uplands,

and although it was unusual for a woman to travel to the remoter mountain

districts, the notion of a lone female wanderer actually fitted with Albanian

custom: the tradition of "Albanian virgins" - women who donned men's clothes

and held a protected status in tribal society - meant that Durham travelled

unmolested.

But her energetic promotion of the Albanians did not earn her many admirers

in Britain. As Rebecca West wrote cattily in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon,

Durham was a member of that class of Balkan travellers who come back "with

a pet Balkan people established in their hearts as suffering and innocent,

eternally the massacree and never the massacrer". Durham sued over

the line.

Some of her stormiest exchanges took place with R. W. Seton-Watson,

professor, editor, government adviser, and himself a kind of spokesman

for Central Europe's national minorities. The Durham–Seton-Watson correspondence,

housed in the Seton-Walson papers at the School of Slavonic and East European

Studies in London, is important not merely for the light it sheds on two

of the most important writers on Balkan affairs of the last century, but

also for the fact that the exchanges reveal something deeper about the

nature of intellectuals and the vicarious grievances they make their own.

During the First World War, Seton-Watson established the journal The

New Europe to champion the emancipation of Europe's subject nationalities,

especially those erupting from the Habsburg empire. The journal called

for "la victoire integrale", a victory that would recognize national rights

and thus secure a permanent peace for the Continent. Collaborators included,

besides Seton-Watson as editor, Tomas Masaryk, the Romanian historian Nicolae

Iorga, and many other important writers on international affairs, including

Durham.

In March 1920, Durham wrote to Seton-Watson complaining about what she

saw as a pro-Serb bias in The New Europe and accusing the editors

of wilfully ignoring the Albanians of Montenegro and Kosovo:

"I have recent information that ever since the armistice

the Serbs have burnt and pillaged Albanian villages, Catholic as well as

Moslem. But New Europe, I know, would deny any such charge and imply

the informant was a liar. If the truth is thus concealed, what wonder that

things go wrong?"

Durham had earlier written a piece on Albanian Bektashi Sufism which, when

printed, was accompanied by a note indicating that the editorial board

did not necessarily agree with the author's points, including her opposition

to the incorporation of Kosovo in the new South Slav kingdom. Seton-Watson

apologized in a return note, mentioning that it was not the board's intent

to insult Durham personally, but merely to dissociate the editors from

the personal views expressed in her article.

Durham quickly wrote back. It was not an issue of personal insult, she

said, but rather a superb illustration of the incredible arrogance of Western

policy-makers in the Balkans. By effectively partitioning the Albanian

lands between an independent Albania and the newly created Kingdom of Serbs,

Croats and Slovenes - eventually to become Yugoslavia - the European powers

were creating the conditions for "a second Armenia". The Albanians,

with no artillery and no planes, would be at the mercy of the Serbian army,

"and the guilt will rest on the Peace Conference". The real tragedy,

she continued, was the inability of those making policy to comprehend the

depth of feeling and intricacies of everyday life in the Balkans. Their

attempts to apply European standards of decency to a land rocked by war

and poverty were doomed. Even when peace agreements were signed, there

was no guarantee that petty officials would not continue to treat minorities

as if they were, by virtue of their blood or religion, still enemies of

the State:

"These men who have never lived months in the Balkans draw

up elaborate clauses about religious rights and minorities which cannot

possibly work .... Even though certain of the intelligentsia in all the

countries have excellent intentions they are quite powerless to restrain

small officials and gendarmes up country."

Durham argued that the solution was quite simply to draw the boundary lines

so as to include as few people as possible under foreign rule. Otherwise,

the threat of violence spreading across newly drawn frontiers was extremely

high, as "half desperate people with little to lose will be ready to rush

into a struggle on the off chance of getting something". Violence could

sometimes turn out to be the most rational response to local oppression

and the ill-conceived plans of foreign peacemakers, not simply a chaotic

bloodletting.

Relations between Durham and Seton-Watson were strained already at the

time of the Peace Conference, which reaffirmed the existence of an Albanian

state but left much of the Albanian nation outside its borders. Over the

years, the source of their disagreements evolved from matters of policy

to more personal disputes over who was more qualified to comment on Balkan

affairs, Durham viewed Seton-Watson as a pointy-headed parvenu. He had

come to the Balkans from the north, through his interest in Slovenes and

Croats in Austria-Hungary, and therefore had little to say about the very

different races to the south. "You I take it made the acquaintance

first of the pick of the Austrian Slavs who owed their culture to generations

of Austrian civilisation", she wrote to him in December 1924,

"and you did not grasp the danger of subjecting them to the Serb savage,

whom you did not know." Durham became even more anti-Serb as time

passed. She was convinced that the Kingdom of Serbs. Croats and Slovenes

was no more than a mask for Greater Serbia. The new South Slav kingdom

was headed by the former Serbian royal house and guided largely by pre-war

Serbian politicians. "Pashitsch & Co.'', she wrote to Seton-Watson

in March 1925, referring to the Yugoslav prime minister, Nikola Pašic',

"have not created a Jugoslavia but have carried out their original

aim of making Great Serbia .... Far from being liberated the bulk of people

live under a far harsher rule than before." Villages had been razed

and atrocities committed, a record of offences that might well push the

minorities in Yugoslavia into the arms of Bolshevik Russia. Her dislike

of Serbian politics and politicians, though, was born more of disaffection

than visceral disdain. "For many years I supported more or less the

idea [of a Greater Serbian state]. It was when I learnt the Serb from the

inside and saw what a retrograde effect on Europe in general the Great

Serb scheme might have that I gave it up and finally opposed it."

*

* *

The rift between Durham and Seton-Watson grew throughout the 1920s,

a mutual bitterness that derived in part from vastly different understandings

of Balkan politics and, increasingly, personal odium. Durham had even begun

to allege publicly that the professor received financial support from the

Yugoslavs and could not therefore be counted on to provide dispassionate

analysis in Britain, She also complained of further personal slights from

Seton-Watson, he now a respected academic and government adviser and she

a freelance journalist. At a Chatham House lecture, Seton-Watson apparently

failed to recognize her raised hand during the question period, and Durham

quickly penned a note to complain of the snub. Seton-Watson responded that

the minor insult of not answering her question paled beside the more grievous

wrong he would have done by trying to respond to her seriously. "We seem

to differ fundamentally on almost every fact connected with the whole Yugoslav

question", he wrote to her in February 1929. "I do not therefore see

what possible good it can do to discuss these matters on the same platform.

I refrained from answering you at the Institute, not because I had nothing

to say, but because I resent most intensely your whole treatment and interpretation

of the question and did not wish to be led into too short a retort."

In early 1929, Arnold Toynbee, then director of Chatham House, stepped

in as voluntary arbitrator. He suggested to Seton-Watson that he and Durham

collaborate on a collection of Yugoslav documents relating to the assassination

of Franz Ferdinand to be published by the Royal Institute of international

Affairs. Both Seton-Watson and Durham had published books on the murder,

but their views were radically different. Seton-Waton's account came close

to exonerating the Serb Government of any complicity in the murder; Durham's

book laid most of the blame for the First World War squarely on Belgrade.

Toynbee had hoped that a joint project might calm both spirits and produce

a truly definitive documentary treatment of the origins of the war.

In his reply to Toynbee, Seton-Walson was uncharacteristically straightforward

about his "open war" with Durham. "I am not disposed to admit

her title as a serious student of history", he wrote, a view that

he claimed was shared by all other commentators on European affairs. "Her

methods of controversy, her reckless and infamously untrue charges against

all and sundry, make it difficult for any friend of Yugoslavia to find

any common ground on which to meet." Durham set out her own position

in a long letter to Seton-Watson in February 1929. Both its tone and content

must have infuriated him, for not only did she attack his reputation as

a scholar, but she also accused him of being the initiator of the childish

sniping that ran between them. She said that she had long worked on the

South Slav question - "in fact, I believe I began to work for South

Slav rights before you did" - and had been a strong proponent of recognizing

legitimate Serb territorial claims. But when she became more familiar with

the lack of civilization among the Serbs, she realized that they were supremely

unfit to rule over other Balkan peoples. Hence her quest to save Albanians

and Macedonians from Serb overlordship. The new Yugoslavia was built

"upon a foundation of crime and lies", an outcome familiar from the

Serb past. "That the history of the Serbs has been a long series of

murders and that as yet they have proved incompetent to form any stable

government is an indisputable fact".

The basic source of Durham's disagreements with Seton-Watson was her

distaste for what she called "strategic" concerns in deciding

the fates of the small nations of Europe. Outside powers stepped in, proposed

some new division of territory, created new national questions while resolving

others, and all the while displayed little concern for the sentiments of

those whose lives were affected by their grand schemes. As she wrote in

her February 1929 letter,

"You seem to regard these populations as mere pawns to

be shifted on the board according to political needs. To me they are all

suffering human beings with whom I have been under fire - for whose sake

I have risked enteric, smallpox and have wrestled with poisoned wounds.

And with whom I have hungered and been half frozen. I feel it a duty to

show the means by which they have been annexed and trampled on. And to

call for a consideration of their cause."

Relations were largely suspended after the late 1920s, which corresponded

to the end of Durham's most productive period. But there was a final, delicious

irony in all this. In 1948, four years after Durham's death, the editor

of the Dictionary of National Biography wrote to Seton-Watson asking

for his evaluation of Durham's contribution to Balkan affairs. His reply

is not among his papers.

The Durham–Seton-Watson correspondence was part of a much larger set

of controversies among British intellectuals early in the last century,

a series of lecture-hall confrontations and salon scandals that Cecil Melville

called "Byzantium in London". While the more frivolous found entertainment

in the cocktail and the saxophone, the more serious took to the new science

of "international affairs". Two aspects of the British character, he wrote,

produced the new craze for foreign relations: one, a sentimental desire

to help the oppressed without asking whether all underdogs were necessarily

good dogs; and second, "the capacity of some of us to salve our consciences

for neglecting the unpicturesque poor of the East End of London by taking

up an interest in the picturesque poor of the East End of Europe".

Eastern Europe has never been short of causes, nor have intellectuals

in Britain, France, America and elsewhere been stow to take them up. One

wonders, though, how recent debates about intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo

will be seen a few decades hence. In time, the dividing lines of the 1990s

and 2000s may appear in nearly as stark relief as those of the 1920s and

1930s. Both the United States and Europe have their share of philes and

phobes, who have deified or maligned entire peoples for reasons that usually

reveal more about the observers than the observed. But, as in Durham's

time, these debates have raised serious questions about writers and the

objects of their passions. What does it mean to be an "expert" on a country

or people? Need one speak the language and "risk enteric", or is it enough

to know the capital's hotels? And can there be a moral component to scholarship,

much less to foreign policy, in a region where the underdogs one year turn

out to be overlords the next? Edith Durham's quirky character and infuriating

diatribes are part of her legacy. But the perspective she offers on intellectuals

and the crusades they take up, on the dilemma of moral commitment and professional

distance, and on the place of compassion and consistency in foreign policy

should be more appreciated than her personality has allowed.

[Back]

* kindly provided by Stephan Nikolov

Durham

was, however, the twentieth century's indispensable interpreter of Albania,

and arguably the most important writer on that culture since J. C. Hobhouse

journeyed through the Albanian lands with Byron. She was adored among the

Albanians themselves, who knew her as "Kralica e Malësorevet" -

the Queen of the Highlanders. "She gave us her heart and she won the

ear of our mountaineers", the exiled Albanian king, Zog, wrote to The

Times on her death in 1944 (even though she was not on good terms with

him, either). The only other Briton to have been so lionized was, improbably,

Norman Wisdom, whom the Communist dictator Enver Hoxha found uproariously

entertaining. Durham's most famous work. High Albania (1909), is valued

by collectors. It is still the pre-eminent guide to the folk customs, social

structure, customary law, religious beliefs and traditional tales of the

Albanians, especially in the highlands north of the Shkumbin river, where

tribal social organization and the distinctive Gheg dialect once set off

the region's inhabitants from the lowlanders to the south. (In 1998, Peter

Hopkirk's fine first edition sold at Sotheby's for £620.)

Durham

was, however, the twentieth century's indispensable interpreter of Albania,

and arguably the most important writer on that culture since J. C. Hobhouse

journeyed through the Albanian lands with Byron. She was adored among the

Albanians themselves, who knew her as "Kralica e Malësorevet" -

the Queen of the Highlanders. "She gave us her heart and she won the

ear of our mountaineers", the exiled Albanian king, Zog, wrote to The

Times on her death in 1944 (even though she was not on good terms with

him, either). The only other Briton to have been so lionized was, improbably,

Norman Wisdom, whom the Communist dictator Enver Hoxha found uproariously

entertaining. Durham's most famous work. High Albania (1909), is valued

by collectors. It is still the pre-eminent guide to the folk customs, social

structure, customary law, religious beliefs and traditional tales of the

Albanians, especially in the highlands north of the Shkumbin river, where

tribal social organization and the distinctive Gheg dialect once set off

the region's inhabitants from the lowlanders to the south. (In 1998, Peter

Hopkirk's fine first edition sold at Sotheby's for £620.)