II. Intelligence in the Roman Empire

Lack of Interest in Intelligence in Early Rome and Reasons for Roman Expansion — Intelligence Service of the Carthaginians, Rivals of the Romans — Hannibal's Mastery of Intelligence — Scipio the Younger Learns from Hannibal — T. Sempronius Gracchus and the Macedonian Relay Service — Cato the Elder Values the Importance of Rapid Information — Slowness of Republican Information System — Messengers and Their Status.

Roman Traders and Financial Agents in Newly Conquered Lands — Mithridates of Pontus, His Intelligence in Asia, Rome, and Spain — Cicero’s Information on Intelligence in Asia — The Pirates and Insecurity of Sea Travel — Caesar’s Understanding of Military, Political, Geographical, and Economic Intelligence— Caesar’s Information on Gallic Intelligence Service — Caesar Establishes Information Service by Relays of Horsemen — His Tragic Death.

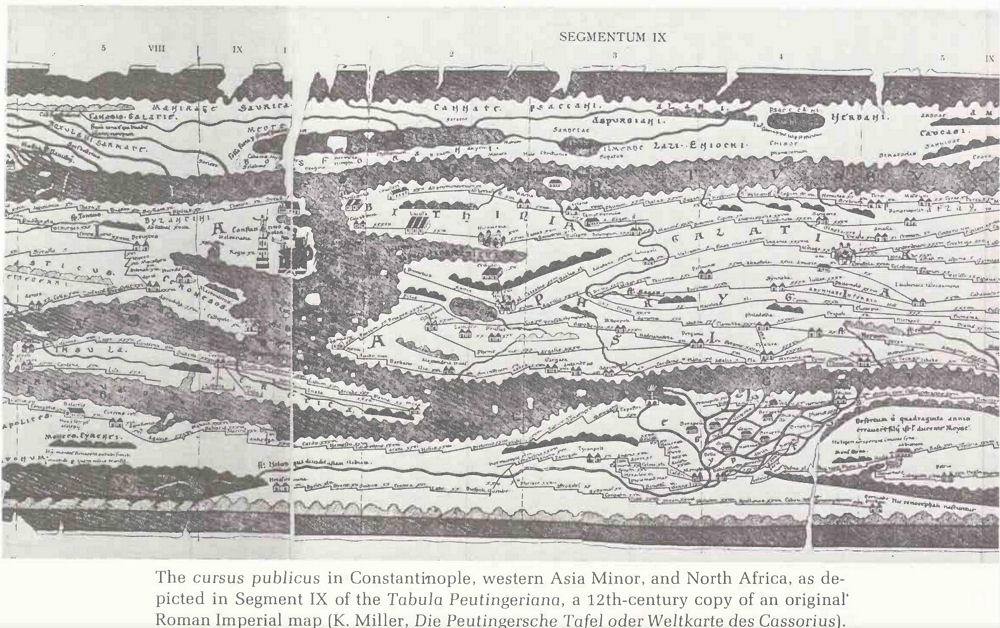

Rise of Octavian-Augustus and Personal Experience in Importance of Intelligence — Founding of the State Post (cursus publicus) — Oriental Influences on Its Organization-Organization of the State Post — The mansiones and Changing-Stations — Transformation of the frumentarii from Grain Dealers to Intelligence Agents — The speculatores and the frumentarii as Intelligence Agents of the Emperors — The frumentarii as Policemen and Agents in Persecution of Christians —

48

![]()

![]()

49

The frumentarii, a Roman “Gestapo”? — Their Suppression by Diocletian — Roman Intelligence from Abroad — Roman and Greek Geographical and Ethnographical Intelligence — Pliny the Elder and Tacitus — The Information Service on the limes.

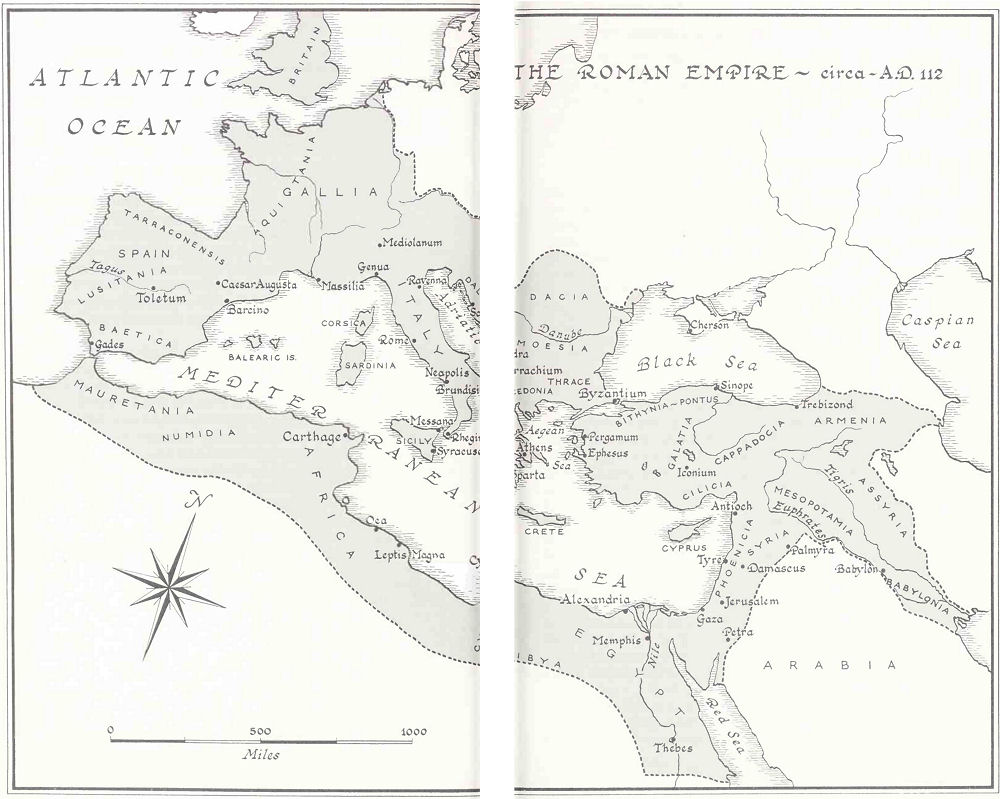

1. Republican Period

When we bear in mind the rapid evolution of intelligence services in the empires of the Near East, and when we consider how greatly the rulers of Egypt. Babylonia, Assyria, and Persia valued good intelligence lor the defense of their countries, for their political expansion, and for the security of their dynasties, it is rather surprising to see that the Romans, whose domination finally extended over the greater part of the ancient Near Eastern empires, manifested in the early period of their history very little interest in intelligence. This fact is the more startling to those who believe that the Roman expansion over Italy, Western Europe, the Adriatic, Greece, the Mediterranean lands, and the Near East was directed from the beginning by ruthless imperialism and a thirst for power and domination. We have seen that a good intelligence service was, in the East, one of the most striking characteristics of absolute power and a basis for successful political expansion.

But this long-held opinion concerning the expansion of Roman power over the ancient world seems to need radical correction. Tim Roman Empire began as a small city-state similar in extent and organization to the Greek city republics. The first conquests which made Rome the dominant power in Latium and southern Etruria were made by powerful Etruscan lords who had established themselves in the city and ruled it as absolute kings. After the expulsion of the alien dynasty and the establishment of a republic, ruled by two consuls elected every year by the Senate, Rome shrank again to a comparatively small state, surrounded by hostile and independent neighbors. In spite of their alliance with the Latins, the Romans made little progress in their campaigns against the Etruscan states that threatened their independence. The Etruscans were weakened by the Greeks advancing from Sicily who wrested from them the mastery of the seas, and by the Celts — the Gauls — who, after establishing themselves in the lands bordering the Adriatic, crossed the Apennines and invaded Etruria proper. Only then were the Romans able to defeat the southern Etrurian states and add their lands to the Roman territory.

![]()

50

All these campaigns were waged by the Romans not so much with a view to conquering new lands as to defending their own independence and very existence. One of the reasons for this slow progress might have been the almost complete lack of any organized intelligence service. We find much evidence of this in the Roman historian Livy’s description of these events. On one occasion, when the Etruscans made a razzia against Rome, according to Livy (Bk. I, 14), only the “. . . sudden stampede [of the farmers from] the fields into the city brought the first tidings of war.” On another occasion (Livy, Bk. I, 37), the city learned of a victorious battle only when the waters of the Tiber brought the shields of fallen enemies inside the walls. The army of the Etruscans, trying to re-establish their expelled king in Rome, seems also to have taken the Romans completely by surprise, although the Senate of the city was, according to Livy (Bk. II, 9-10), aware of the danger from this quarter threatening the existence of the new Republic. Nevertheless, apparently no precautions were taken, and the citizens hastily withdrew from their fields to the city when the enemy appeared. And the enemy would have captured the Capitol but for the bravery of Horatius Codes who, singlehanded, stopped the onrush of the Etruscans from the Janiculum. He gave his friends time to demolish the bridge over the Tiber, then swam across the river in full armor, a feat forever remembered in Rome.

As the territory of the Roman state in its early evolution could easily be crossed in a one-day march, it would not have been difficult to establish a kind of information service, but the Romans do not seem to have thought of it. According to Livy, the Romans were also surprised in 390 b.c., when the Gauls, enraged by the fact that Roman envoys, contrary to international custom, had taken up arms to fight on the side of their enemies, marched against the city. Although this report of Livy (Bk. V, 37) seems exaggerated, the disastrous defeat which the Romans suffered would have resulted in a complete destruction of the city, had the defenders of the Roman Capitol not withstood the long siege. This again leads us to the conclusion that the Romans underestimated the necessity of securing good information as to the nature, the intentions, and the movements of their neighbors and rivals. The famous incident during the siege of the Capitol by the Gauls (Livy, Bk. V, 47), when the cackling of geese awakened the sleeping defenders who, thanks to this lucky incident, were able to drive away the Gauls scaling the walls, can be quoted as another example of the Roman lack of experience in basic principles of intelligence in the early stages of their history.

![]()

51

Rome recovered after the withdrawal of the Gauls and continued the warfare against southern Etruria which, at that time, was her most dangerous foe. She succeeded not only in subjugating the southern Etrurian tribes, but also in re-establishing her prestige among the Latins; by 343 b.c. the first stage in the Roman conquest of Italy was closed. The discord among the Samnites and Apulians, the two mighty Etruscan tribes in southern Italy, was of assistance to Rome, then acting as protector of Latium and Campania, not only in pacifying these and other hostile tribes, but in extending her supremacy over a great part of southern Italy, and in putting her in direct touch with the Greeks who had advanced thither from Sicily.

These rapid advances in southern Italy alarmed the northern Etruscans, who then attacked Roman territory. This incident opened a new period in the Roman conquest of Italy and led to the defeat of the Etruscans and their new allies, the Gauls, established in the Po Valley. Further Roman progress in the south was again inaugurated, not by Roman lust for power, but by the appeal for help from the Greek cities on the southern coast of Italy, harassed by the Sabellian tribes on their borders. When Tarentum. the most powerful of the Greek cities, later changed its policy towards Rome and appealed for help to Pyrrhus, King of Epirus and one of the most brilliant Greek generals produced by the age of Alexander the Great and his successors, the Romans for the first time crossed swords with the Greeks. Only the stubborn determination of the Senate saved the Romans, twice defeated by the adventurous king. The conflict ended with the submission of Tarentum and the retreat of Pyrrhus to Greece. This conflict brought the Romans into contact with the Phoenicians or Carthaginians, who were masters of a great part of Sicily. The first contact was friendly-an alliance against the common danger coming from Pyrrhus.

Conflict with Carthage became inevitable, however, when Rome tried to protect her own interests and those of her allies in Italy. Carthaginian power was established in Sicily, in Sardinia, and in Corsica. It was evident that the Phoenicians were aiming at complete supremacy of the seas and the monopolization of all commerce in the Mediterranean Sea, the realization of which would have been disastrous for both Rome and Italy. The struggle which ensued between the two most powerful cities of that time became a fight for life or death. It resulted first in the annexation of Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia by the Romans, but it could also have ended the role of Rome as a great power in Italy. The struggle for the Po Valley, where the Gauls were established and which was conquered after the first so-called Punic War, was renewed by the unruly Gauls themselves,

![]()

52

who in 225 b.c. had once more crossed the Apennines and come within three days’ journey of Rome. Spain became a great menace to Rome when the Carthaginians, trying to compensate for the loss of the great Italian islands, established themselves there and began to use Spain as the base for the invasion of Italy and the destruction of Rome itself.

The defense of Italy, and of its commerce in the Adriatic Sea, brought the Roman legions into the neighborhood of Macedonia and Greece following the destruction by the Roman navy of the vessels of the Illyrian pirates (228 b.c.); the pirates had endangered the seas with their raids, and the Roman envoys were welcomed as friends by the Greek city-states.

The destruction of Carthage, weakened by the ruinous wars with Rome, was perhaps unnecessary, but this cruel vengeance on a defeated enemy is explained by the anxiety to risk no longer the danger from Africa, which generations of Romans had had to face. Finally, the conquest of Macedonia was undertaken in order to protect Italy and Rome from that quarter. The Romans had not forgotten that Philip V of Macedon concluded an alliance with Hannibal, that most dreaded Carthaginian leader, and the Senate had good reason to mistrust the ambitious King Philip and his successor, Perseus. Similar reasons caused the wars with the Seleucids, which finally brought the Romans into Asia Minor and Syria.

All this resulted in an immense expansion of Roman power, an achievement never imagined by the first rulers of the small city-state on the Tiber. It was not the realization of plans elaborated upon in advance by generations of Roman leaders envisaging the greatest political expansion of the Republic; rather, it was brought about by a series of incidents unforeseen, mostly unprovoked and unexpected. All these successes were the fruit of a stubborn and indomitable will on the part of the Romans who, even in their darkest moments when Rome’s walls echoed the cries of the approaching enemy, never lost courage, by the individual genius of great leaders, descendants of the old Roman families, and by the compactness of the Italian confederacy forged by Roman statesmen. In the hour of its greatest danger, the inhabitants of the peninsula perceived clearly that their safety would be secured only under Rome’s leadership.

We are entitled to think that the climb to this supremacy would have been easier and less costly for the Romans had they paid more attention to the importance of a good information service. But it seems that the simple, straightforward, unspoiled Roman peasant stock, the basis of the proud Roman race, looked with supreme disdain upon anything which appeared artificial and disingenuous.

![]()

53

During the whole existence of the Roman Republic, we find no single trace of any organized system for obtaining information on developments among neighboring peoples, or of the plans of the enemy. We look in vain for evidence that the Romans used even the most primitive means of transmitting intelligence as, for example, by fire or smoke signals. They seem to have relied, in the early Republican period, on information given them by their allies of the movements of dangerous neighbors. We find numerous pieces of evidence of this kind in Livy’s historical work. From the manner in which he describes this kind of information, we have the impression that the Romans themselves had not even thought of establishing a systematic intelligence service and that they possessed no special agents among the befriended and allied tribes. They left it entirely to their allies to keep them informed of events which might endanger their common interests. Livy’s description tells us that this voluntary information service worked quite well as long as it was in the interest of the befriended tribes to keep Rome informed. It naturally collapsed when the tribe became hostile to Rome and succeeded in persuading its neighbors to its own plans. Other sources of political information were the Roman and Latin colonists who settled in important places in the conquered territories. But no systematic service was organized there either, and it was left to the colonists themselves to find means by which the capital could be kept informed of dangerous developments in their area. It was the reputation of Roman toughness and energy and the trust in Roman fidelity to her allies — the fides Romana — which kept this primitive information service going.

Moreover, we do not see any marked progress in military intelligence. The Roman legions of course used the basic strategic ruses and arts common to all peoples, and often profited from information elicited from traitors and deserters, but the Senate and its consuls in the field experienced difficulty keeping in touch, as there was no organized courier service between the fighting forces and the homeland.

It is easy to understand that such a situation was full of danger and often put a great strain on Roman diplomacy and the military forces. This neglect of an intelligence service by the Romans was outweighed by diplomatic and military superiority only as long as they were dealing with the disunited tribes in Italy. But once they faced an enemy who himself knew the advantages of good intelligence and used it shrewdly, they were obviously placed in a very unpleasant situation, and this they realized during their prolonged struggle with the Phoenicians of Carthage.

![]()

54

The so-called Punic Wars were a hard school in which the Romans learned the importance of intelligence, and they paid for it heavily.

Owing to their frequent commercial intercourse with Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor, the Carthaginian Phoenicians — the city of Carthage was founded by the Phoenicians of Tyre in Syria — were well acquainted with all that took place in the Near Eastern countries. They knew of the elaborate information services which had been developed in those lands, and they were shrewd enough to apply for their own benefit the methods used by Near Eastern monarchies. The Carthaginians were daring seafarers and applied the principles of good information service to their foreign trade. They explored the Spanish coast and the west African coast, and founded settlements in modern Senegal and Guinea, in Madeira and the Canary Islands.

Herodotus’s History (Bk. IV, 196) provides an interesting report on the Carthaginian use of the signal service in their commercial dealings with the natives of the west African coast. When the Carthaginian merchants disembarked, they put up smoke signals to announce their arrival to the natives with whom they wished to exchange their merchandise. The natives replied to the signals and deposited at a certain distance from the sailors the amount of gold they were willing to offer for the merchandise brought by the Carthaginians, and then withdrew. The merchants inspected the gold and, if they judged it to be sufficient, unloaded their merchandise from the vessels. If the quantity of gold was judged to be insufficient, further signals were made until both sides were satisfied, and the transaction concluded.

The Carthaginians jealously guarded their trading monopoly; after establishing themselves in Sardinia and Corsica, their squadrons watched for the vessels of other nations, and seized every ship which ventured into the Mediterranean between Sardinia and the Straits of Gibraltar. They appear to have discovered tin mines in northwestern Spain and guarded their secret so well that the Greeks never learned their location, and thought that the tin came by sea from tiny islands somewhere off the northwestern coast of Spain. Strabo, the geographer of the first century b.c., describes in his Geography (Bk. III, 5.11) the method used by the Carthaginians to keep their secret: “In former times it was the Phoenicians alone who carried on this commerce . . . ,” for they kept the voyage hidden from everyone else.

![]()

55

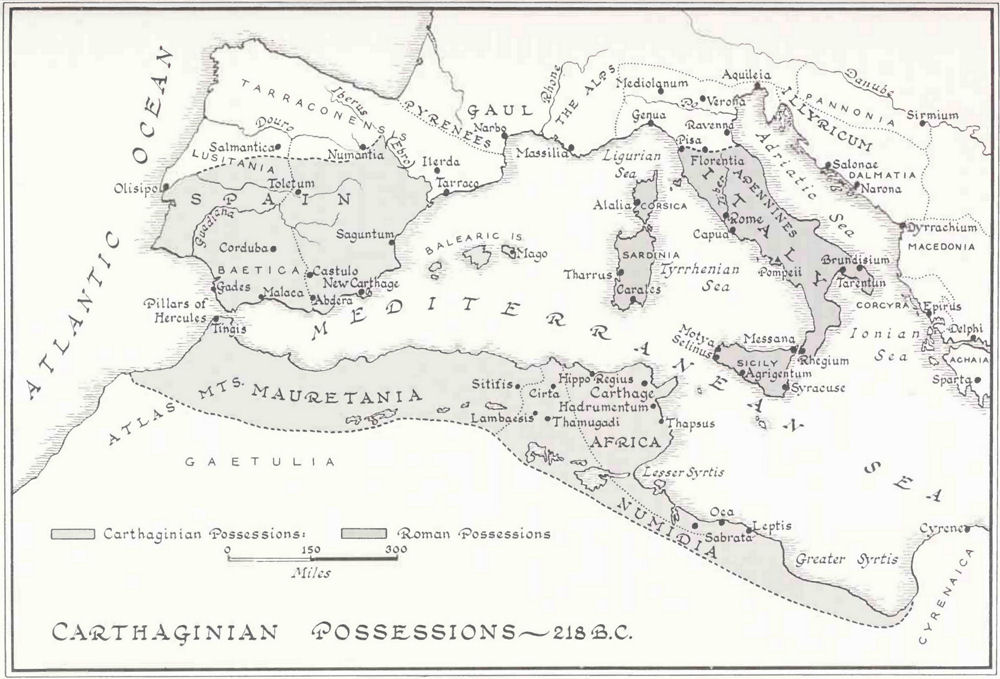

Carthaginian Possessions ~218 b.c.

![]()

56

And when once the Romans were closely following a certain ship-captain in order that they too might learn of the markets in question, the ship-captain out of cunning purposely drove his ship from its course into shoal water; after he had lured the followers to the same ruin, he himself escaped by holding on to a piece of wreckage. He received from the state the value of the cargo he had lost. This incident, which impressed the Greeks very much, does indicate that the Carthaginian senate was aware of the value of secrecy in foreign trade relations and jealously watched over the monopoly of important commercial information.

The Carthaginians availed themselves of their knowledge of the Eastern information system for the first time in their warfare in Sicily. There is some evidence that they established a reliable intelligence service from the theater of war in Sicily to the coast of Africa. The author of an essay on strategy — Polyaenus. who lived in the second century of our era — gives us the following data in Book VI, 16.2, of his work:

When the Carthaginians were devastating Sicily, they made, in order that all they needed would be sent to them quickly from Libya, two waterclocks of the same size, on which they marked circles with appropriate inscriptions. These were the inscriptions: “We need war ships, cargo boats, machines for besieging, foodstuffs, cattle, arms, infantry, cavalry.” When they had put these inscriptions on the clocks, they kept one of them in Sicily and the other they sent to Carthage with the following instruction: “They [the Carthaginians] must watch and when they see a fire signal in Sicily, they should let the water flow from the water-clock in Carthage. When they see another fire signal, then they should stop the flowing of water and see which circle it had reached. When they had read the inscription they should send in the quickest way the things they had been asked for by these signals.” And so it came about that the Carthaginians were always provided in the most rapid way with what they needed in their warfare.

The system described by Polyaenus resembles in almost every detail that minutely depicted by Aeneas, the first Greek writer on strategy. It is possible that Polyaenus simply copied verbatim from Aeneas. It is also possible, however, that the system described by Aeneas was not invented by him but was known to the Creeks and Carthaginians before his time. Nevertheless, even if it were true that Polyaenus had simply copied the water telegraphic system from Aeneas, it remains evident from his report that the Carthaginians had established, during their invasion of Sicily, a satisfactory system of information service which functioned well across the sea.

![]()

57

Further interesting information on Carthaginian military intelligence during the first Punic War is given by Polybius in his Histories (Bk. I. 19.6), where he describes how the Carthaginians used fire signals and messengers.

Generally speaking, the Carthaginians must have been regarded by the ancients as past masters in the methods used by intelligence agents and spies. For example, the invention of the clever stratagem of sending secret information by writing on a wooden tablet before it was covered with wax, in order to give the impression that the traveller possessed only a wax tablet for his own use, is ascribed to the Carthaginians by the ancient historian Justin (Bk. XXI. 6.6) who ascribes it to Hamilcar Barcas. In fact, this way of sending secret intelligence might have been known before their time but its invention may have been credited to the Phoenicians from the Syrian coast from whom Carthaginians and Greeks might have learned it. We shall see, however, that Hannibal was familiar with the use of secret signs and symbols, agreed upon beforehand, by which his secret messengers could be recognized as bearing a message from him. Plutarch, moreover, in his Life of Fabius Maximus (ch. 19) describes Hannibal’s custom of sending forged letters containing false information to mislead his political and military opponents.

This is not all. It seems that the Carthaginians possessed an elaborate system of relays and speedy messengers, at least on the coast, by which the capital was kept informed of any complications that might endanger its security. We find evidence for it again in Livy, who reports (Bk. XXIX, 3.8) that when Laelius had effected the night landing of a Roman army near Hippo in Africa in 205 b.c., the senate of Carthage was informed of this occurrence the very next day. As the distance between Hippo and Carthage is about 250 km., the news could not have reached the capital in so short a time without an elaborate organization of messengers and numerous relays established in advance. We do not know whether this service was a permanent institution, as in Persia, or whether it functioned only during time of war. In any case, the Carthaginians were well aware of the importance of reliable intelligence being rapidly communicated to responsible political authorities.

All forms of fast and shrewd intelligence known to the Carthaginians were developed in the cleverest way by the greatest Punic hero, Hannibal, during the second Punic War. The information service which the Carthaginians had established during their campaign in Sicily must have been extended to Spain when the Carthaginians, under Hamilcar and his son-in-law Hasdrubal had begun its conquest.

![]()

58

At least, we learn from the Greek historian Appian that Hannibal, who succeeded Hasdrubal as commander in Spain after the latter’s death, constantly sent messages to the Carthaginian senate endeavoring to acquaint its members with his plan of launching a conflict with Rome. As we gather from the reports of Livy, Appian, and Cornelius Nepos that the Carthaginians were always well informed as to the events in Spain, so we must suppose that they had established a well-organized information service between Spain and Libya, perhaps a combined service of messengers sent both by land and by sea.

From Livy we learn a few interesting details about this service which was probably perfected by Hannibal. When describing the encounter of the Romans with the Carthaginians led by Hasdrubal, Hannibal’s brother, Livy discloses how the Roman fleet was sighted by the enemy (Bk. XXII, 19):

The Spaniards have numerous towers built on heights, which they use both as watch-towers and also for protection against pirates. From one of these the hostile ships were first descried, and on a signal being made to Hasdrubal, the alarm broke out on land and in camp before it reached the sea and the ships; for no one had yet heard the beat of the oars or other nautical sounds, nor had the promontories yet disclosed the fleet to view, when suddenly horsemen, sent off by Hasdrubal, one after another galloped up to the sailors, who were strolling about the beach or resting in their tents and thinking of nothing so little as of the enemy or of fighting on that day, and bade them board their ships in haste and arm themselves, for the Roman tleet was even then close to the harbor.

This rapid transmission of military intelligence saved them from disaster. Be it said that the Romans, in this particular case, owed their own information as to the possibility of a surprise attack to Greek sailors in the service of the city of Marseilles (Massilia), their ally. This intelligence service organized in Spain by the Carthaginians must have greatly impressed the Romans, since Pliny the Elder mentions it in his Natural History (Bk. 35, xlviii. 169) and ascribes the organization to Hannibal.

Hannibal made full use of this information service. His messengers were faster than the envoys from the Roman Senate who met him under the walls of Saguntum. which had put itself under Roman protection. When the Punic general refused to abandon the siege of the city, the Romans sailed to Carthage with the Saguntine envoys who had come with them from Rome. But, although the Romans held supremacy of the sea at that time, Hannibal’s messengers reached Libya before them and still had time before the arrival of the

![]()

59

Roman envoys “so that they might prepare the minds of Hannibal’s adherents to prevent the opposing party from affording any satisfaction to the Roman people,” as Livy himself reports (Bk. XXI, 9). The Roman envoys appear to have been very poorly informed of the political situation in Carthage, and lost time when they naively asked the Carthaginians to deliver Hannibal to them as a violator of the treaty concerning Spain concluded between Rome and Carthage.

The further development of the conflict proved once more how much the Romans lost by neglecting their intelligence service. Immediately after the capture of Saguntum, Hannibal, by peaceful means or by force, subdued most of the Spanish tribes and made preparations to invade Italy from Spain, through Caul and the Alps. Agents were dispatched to the different tribes of Caul, and most of them were won over before the Romans had any knowledge of what was happening. According to Appian (Bk. VI, 3.13), Hannibal “sent his agents also to the Alps and caused an examination to be made of the passes of the Alps, which he traversed later”; leaving his brother Hasdrubal in command in Spain, he started his Italian expedition. This prior exploration of the passes through the Alps, also reported by Livy (Bk. XXI, 23) is an interesting detail. We know that the geographical knowledge of the ancients was very poor. Although the Phoenicians were certainly familiar with the coastal areas of Spain and Gaul, their information about the Alpine passes which led from the Rhone Valley in Caul to the Po Valley in northern Italy was deficient. Hannibal neglected nothing, and, before embarking on this difficult expedition, he endeavored to learn as much as possible about the country his army would cross.

The Punic general kept his preparations for battle so secret that Rome did not even consider the possibility that Italy might become the theater of war between their troops and the Carthaginians. How poor their information service was can be seen from the account given by Livy (Bk. XXI, chs. 19, 20). The Roman Senate instructed its legates, who were returning from Carthage to Spain, to get into touch with the different Spanish and Gallic tribes and to win them over to the Roman cause. But Hannibal’s agents had been quicker, and the Roman legates, “Being then bidden straightway to depart out of the borders of the Volciani, they received from that day forth no kinder response from any Spanish council. Accordingly, having traversed that country to no purpose, they passed over into Gaul.”

But Hannibal’s agents had already done their work in Gaul. Let us read Livy’s description of the reception given to the Roman envoys:

![]()

60

When the envoys, boasting of the renown and valor of the Roman people and the extent of their dominion, requested the Gauls to deny the Phoenician a passage through their lands and cities, if he should attempt to carry the war into Italy, it is said that they burst into such peals of laughter that the magistrates and elders could scarcely reduce the younger men to order, so stupid and impudent a thing it seemed to propose that the Gauls should not suffer the invaders to pass into Italy, but bring down the war on their own heads and offer their own fields to be pillaged in place of other men’s.

The envoys’ mission to Gaul ended in a complete failure, “nor did they hear a single word of a truly friendly or peaceable tenor until they reached Massilia [Marseilles].” And here the old story was repeated. The Greek colonists of Marseilles, being Roman allies and aware that a victory by the Carthaginians could spell complete ruin for their trade and reduce their city to poverty, tried on their own, and in their own interests, to obtain all possible intelligence as to Hannibal’s plans. It was from their allies that the Roman envoys learned the truth, as is reported by Livy: “Here [in Marseilles] they learned of all that had happened from their allies, who had made inquiries with faithful diligence. They reported that Hannibal had been beforehand with the Romans in gaining the good will of the Gauls, but that even he would find them hardly tractable . . . unless from time to time he should make use of gold, of which the race is very covetous, to secure the favor of their principal men.”

In the meantime, let us again quote from Appian [Bk. VI, 3.14): “[The Romans, thinking that] Spain and Africa would be the scene of the war — for they never dreamed of an incursion of Africans into Italy — sent ... 160 ships and two legions into Africa. . . . They also ordered Publius Cornelius Scipio to Spain with sixty ships, 10,000 foot, and 700 horse. . . .” Thus nothing was known in Rome of Hannibal’s daring plans. The Roman envoys apparently made no attempt to send to Rome as rapidly as possible the information they had gathered in Gaul and in Marseilles. So it came about that when the envoys reached Rome, the two armies were already on their way to Spain and Africa. “They found,” says Livy, “the citizens all on tip-toe with expectation of the war, for the rumor persisted that the Phoenicians had already crossed the Ebro” in Spain. In reality, while these rumors were circulating in Rome, Hannibal had crossed the Pyrenees and was on his way through Gaul to the Alps.

Again it was the Massilian Greeks who proved to be better informed and who transmitted their intelligence to their allies. When Publius Cornelius Scipio reached the harbor of Marseilles with his fleet,

![]()

61

he was informed by the Massilian merchants that Hannibal had already crossed the Pyrenees and was about to ford the river Rhone. Publius sent a contingent of his cavalry together with Gallic auxiliaries in the service of the Massilians with the Massilian guides to investigate the situation. According to Livy (Bk. XXI, 29). Hannibal very quickly received intelligence that a Roman army was in Marseilles, and his horsemen, sent to reconnoiter the whereabouts of the Romans, clashed with a Roman detachment. Although the Roman consul would have welcomed a battle with the Phoenicians before the latter crossed the Alps, so as to stop their advance, or at least to weaken the enemy and make him less formidable should he reach Italian soil, Hannibal avoided battle and marched towards the Alps. And here again we find evidence of the insufficiency of Roman intelligence. According to Livy (Bk. XXI, 32), the consul learned of the departure of the Phoenicians towards the Alps only “some three days after Hannibal had left the bank of the Rhone.” Unaware of what happened, “he marched in fighting order to the enemy’s camp, intending to offer battle without delay. But finding the works deserted, and perceiving that he could not readily overtake the enemy, who had got so long a start ahead of him, he returned to the sea, where he had left his ships.” Publius Scipio had good reason to be afraid that Hannibal might take the Romans completely unawares on the other side of the Alps. He knew that no one in Rome expected anything of this sort and that no precautions had been taken. The attitude of the Gauls, mostly friendly to Hannibal, must have given him the impression that the Phoenicians might have come to an understanding also with the Gauls in the Po Valley. He therefore sent his brother with the army to Spain, and himself returned to Pisa, his port of embarkation, in order to alert the Roman troops stationed on the other side of the Apennines.

These details, chosen on purpose, show us more clearly than anything else the inferiority of the Roman intelligence service. The Persians, or the ancient Egyptians, would hardly have been taken so off guard by the sudden invasion of an enemy as were the Romans when Hannibal invaded Italy proper. It is almost incredible that the Romans had not introduced at least the basic methods of transmitting intelligence after their experiences during the first Punic War. According to Livy (Bk. XXI, 33), even the Gauls possessed a kind of signal service and put it into use in order to warn their countrymen and to announce Hannibal’s approach. Hannibal, of course, used this kind of signalling, familiar to the Carthaginians, during his campaign.

![]()

62

Livy (Bk. XXI, 27.7) and Polybius (Bk. III, 43.6), describing the fording of the Rhone by Hannibal, confess that this kind of signalling worked perfectly. To our surprise we find nothing of this kind on the Roman side.

It seems obvious from Livy’s report (Bk. XXVII, chs. 39, 43) that Hannibal, during his prolonged stay in Italy, kept in touch by messenger with his brother Hasd rubai who was fighting the Romans in Spain. Again, an incident which proved fatal to the Carthaginians shows the carelessness of the Romans even when they intercepted the enemy’s intelligence in their own country, although they were fighting for their very existence. When Hasdrubal, called by his brother to come to his help in Italy, had crossed the Alps and had abandoned the siege of the city of Placentia, he sent four Gallic horsemen and two Carthaginians with a letter to Hannibal announcing his arrival. The six riders traversed the whole of Italy without difficulty, although they must have been conspicuous as strangers to many. Only the fact that they were not familiar with the roads in southern Italy attracted the attention of Roman soldiers who roamed about the country foraging, and they were brought before the Roman military authorities. Hasdrubal’s letter was discovered, saved Rome from a very unpleasant situation, and became one of the causes of Hannibal’s final defeat in Italy. Thanks to the interception of this letter, the Romans were able to surprise Hasdrubal and destroy his army. Hannibal learned of this great misfortune only when the Romans sent him the head of his unfortunate brother, slain in the battle.

We learn, again from Livy (Bk. XXIII, chs. 33, 34), of another similar incident which shows once more how slow and awkward the Romans were in learning the secrets of intelligence. Hannibal’s initial success in his Italian campaign induced Philip V, King of Macedonia, to listen to the Phoenician’s exhortations and to conclude an alliance against Rome, their common enemy. He sent an embassy to Hannibal. These ambassadors reached Italy safely but on their way to Hannibal’s camp in southern Italy were intercepted by the Romans near Capua and conducted to a Roman praetor. Asked about the object of their journey, they declared impudently and with great emphasis that they were sent by the King of Macedonia to the Roman Senate with warmest greetings and an offer of alliance between Macedonia and Rome against Carthage. The praetor, pleased with such a discovery and eager to be useful to the ambassadors and to the Roman Senate, received them with great honor and lavishly provided them with all they needed for their long journey, instructed them which route to take and disclosed to them in detail the position of the Roman and Carthaginian armies.

![]()

63

The ambassadors, making use of this information, had no difficulty in reaching Hannibal’s camp and of informing Hannibal of Philip’s plans. The Phoenician was, of course, delighted and sent them back to Philip with his own proposals. The legates safely reached the vessel which had brought them to Italy and had lain hidden on the coast undiscovered by the Romans, but they were intercepted on the high seas by a Roman squadron. They would have escaped safely even this time. Their explanation seemed quite plausible to the Roman admiral. They said they were on their way to Rome and that, after having left the praetor, they were afraid of falling into the hands of the Phoenicians if they continued by land, and therefore were trying to return to Rome by sea. Unfortunately, Hannibal had sent with them two of his own men and it was their Punic appearance which aroused the suspicion of the admiral and brought the whole project to an unhappy end.

Hannibal owed the astounding success of his armies in Italy not only to his military genius, but also to this skillful use and shrewd application of every item of political and military intelligence. He invented a series of new strategies by which he again and again outwitted the Roman generals. He was able to communicate with his sympathizers in Italy behind the backs of the Romans; he had the means of learning the enemy’s plans quickly; and the rapidity of his movements was often so astounding that in spite of its final lack of success, his campaign in Italy remains the greatest achievement of military strategy and intelligence in the classical period. It is highly interesting, for example, to read Polybius's account (Bk. VIII, chs. 24-33) of the maneuvers by which Hannibal first kept secret his negotiations with his young sympathizers in the city of Tarentum, then in Roman hands, and by which he directed the occupation of the city without any losses. The whole operation was a triumph of military tactics combined with the shrewdest sense for intelligence. The same can be said of the operations by which he tried to relieve his besieged allies in Capua, and his sudden and absolutely unexpected appearance before the walls of Rome. Polybius’s description fBk. IX. chs. 4-8J of these events is very vivid. The universal panic and consternation which his appearance caused among the population of Rome again bears testimony not so much to the poor state of the Roman intelligence service — although Polybius seems to believe that Rome was taken completely unawares — as to the dread which the name of Hannibal inspired among the Roman populace.

![]()

64

In this case, Rome was not altogether surprised. According to Livy (Bk. XXVI, chs. 8, 9), intelligence of Hannibal’s plan was obtained by the besiegers of Capua from deserters and sent to the Senate. Furthermore, a messenger was dispatched from Fregellae by the proconsul Fulvius, who was following Hannibal, to report that the Phoenicians were marching on Rome. The messenger covered the distance from Fregellae to Rome — 100 km. — in one day and night, a remarkable achievement. But Hannibal eluded the enemy, as he took an unexpected route and surprised everyone by the suddenness of his appearance under the walls of Rome. It was Roman stubbornness in refusing to abandon the siege of Capua and the arrival of Fulvius’s legion at Rome that spoiled Hannibal’s plans.

Livy’s report shows that the Romans had begun to learn the importance of rapid intelligence in the hard school of fighting Hannibal, but they made slow progress. At the beginning of the second Punic War, as we have already seen, for example, they relied on the Greeks from Marseilles. Scipio the Elder clearly saw the superiority of the Massilians in this field, and during his Spanish expedition rapid Massilian cruisers rendered the Romans great service in this respect. This is duly acknowledged by Polybius (Bk. III, 95).

The first evidence we have that the Romans had begun to apply the system of relays in signalling military intelligence is found in Livy’s account (Bk. XXIV, 46) of the capture of Arpi, in Apulia, in 213 b.c. during the second Punic War, by the consul Fabius. It was the first lesson learned by the Romans from Hannibal.

Another example of the progress made by the Romans is the precautions taken by them in 208 b.c. when their consul Marcellus was defeated by Hannibal and slain in battle. Hannibal took possession of the consul’s seal ring. This time the Romans, knowing Hannibal’s habit of using forged letters, acted surprisingly fast. According to Livy (Bk. XXV11, 28), the other consul Crispinus “fearing some trickery might be contrived by the Carthaginian through a fraudulent use of that seal, sent word around to the nearest city-states that his colleague had been slain and the enemy was in possession of his ring; that they should not trust any letters written in the name of Marcellus." It was a timely warning, for hardly had this intelligence reached the city of Salapia before a Roman deserter, impersonating the late consul’s messenger, brought Hannibal’s forged letter sealed with Marcellus’s ring, asking the citizens to be ready for the reception of the consul. This timely warning saved the city and brought about the slaying of Roman deserters who preceded Hannibal’s army to give the impression that Romans were approaching:

![]()

65

they were let into the city and, when the gates were closed, were massacred.

In spite of the progress made by the Romans during the second Punic War in the appreciation and organization of intelligence, they still remained inferior to their teacher for a long time. Hannibal proved superior in this respect until his death. When he had returned to Africa after his unsuccessful campaign in Italy, Carthage achieved a new prosperity under his direction in spite of the ruinous conditions of peace imposed on the city. The Romans, alarmed at this, demanded Hannibal’s extradition, but the Phoenician hero made a theatrical escape which was a great feat of planning and shrewd intelligence. It is worth reading the account of this escape as related in Livy (Bk. XXXIII, chs. 47, 48).

The Roman historian cannot hide his admiration for this exploit, and it was an achievement. In one night, on horseback, Hannibal rode about 226 km. to his castle by the sea, probably using the relay system of the state post; in spite of his fatigue, he crossed from there by boat to the island of Cercina. He was able to think fast, to outwit the wily Phoenician merchants in the port, to outdrink their sailors, and to escape secretly during the night.

Hannibal went to Antioch where he was well received by the Seleucid King Antiochus III. The king was hostile to the Romans and listened to Hannibal’s plans for a new attack against them with the help of Syrian and Carthaginian forces. Following the king’s acquiescence to this plan, Hannibal sent his agent Aristo, a Phoenician from Tyre, with precise instructions, but no written document, to Carthage. This was brilliant, because Aristo, when questioned by the Carthaginian authorities as to whether he had brought any secret letters to Hannibal’s friends, could declare in good conscience that he had delivered no written secret document to anyone in Carthage, a statement which could be confirmed again with emphasis by all concerned. But Hannibal, forgetting nothing, disclosed to Aristo some secret signs by which the members of his political party in Carthage would undoubtedly recognize that he enjoyed plenary powers from their leader.

In Carthage, the real purpose of Aristo’s mission soon became known in political circles. Although, according to Livy (Bk. XXXIV, 61), Aristo’s negotiations with Hannibal’s friends lasted for some time and finally led to an official investigation by the authorities, the Romans knowing nothing of what was brewing. If Aristo’s mission had been successful, they would have been surprised again, as they seem to have had no secret agents either in Syria or Carthage,

![]()

66

although both countries had been recently conquered and were still regarded with great distrust. But the peace-loving party in Carthage won the day and the Carthaginians sent their own embassy to Rome to inform the Senate of the plot that was brewing, at the same time assuring them that Carthage did not wish to have any part of it. The affair was also reported to Rome by Carthage’s neighbor and rival, King Masinissa, a Roman ally whose information service in Africa was better than that of the Romans. Roman wrath pursued Hannihal in his exile and finally, in order to escape extradition to his mortal enemies, the great Phoenician hero took poison.

The second Punic War certainly would not have been so costly for the Romans had they learned more quickly the need for a rapid intelligence service. It must be said that the hero — Scipio Africanus the Younger — who played a decisive part in the Roman victory of the third Punic War which definitively sealed the fate of Carthage, made the greatest progress in the art of military and political intelligence. It seems that he had not only profited from the lessons given by Hannibal and the Carthaginians, but also from those of the Greek historian Polybius. During the Roman campaign against Philip V of Macedonia which followed the second Punic War, this Greek became a great admirer of the Romans and later a personal friend of Scipio. He regarded it as his patriotic duty to reconcile his compatriots to the necessity of accepting Roman supremacy. In his historical work he tried to explain that because of its fine constitution, its great moral qualities and military valor, the Roman people was predestined by Fate to rule the world. He studied the Punic Wars in detail, and it was not hard for him to discover the reasons for the initial success of the Carthaginians. He was well acquainted with the organization of the intelligence service in the states created by Alexander’s successors, and he had the opportunity of studying on the spot the system used by Philip of Macedon during his campaign in this country on the side of the Romans. In this respect also, as in so many other things, he appears to have been Scipio’s teacher.

And Scipio seems to have put into practice what he had learned in this school during his victorious campaign against the Carthaginians in the third Punic War. Polybius may have given him many suggestions in this respect as he accompanied his friend to Africa and together with him witnessed the flames which destroyed the conquered city. How Scipio applied the methods of the old Persian information service to military intelligence we learn from the description of the siege of Numantia (134-133 b.c.), an important city in northern Spain.

![]()

67

Polybius was there with his friend under the walls of this city and seems to have described this memorable siege in a work, now lost, which was intended as a supplement to his Histories. Fortunately the tactician Appian was so much impressed by the new methods employed by Scipio on this occasion that he appears to have copied its most characteristic features.

We learn from his description (Bk. VI, chs. 90-93) that Scipio combined very cleverly the system of information transmitted by relays, posts, messengers, fire signals, and, during the day, signals by red flags — which replaced smoke signals and were a great improvement-and vocal announcements. The service functioned perfectly; thanks to this highly developed method of military intelligence, all the attempts made by the valiant Spaniards to break through the Roman lines were beaten back and Numantia forced into surrender. We can see in this description all the main elements of the Persian method of rapid transmission of important intelligence here applied to a particular military problem. Only Polybius could have suggested such an idea, as he was well acquainted with the Greek literature which describes the Persian invention.

Although the practical application of the method met with full success and made a great impression on their contemporaries, the Romans failed nevertheless at that time to grasp the whole idea and to apply it to their political intelligence. This is the more curious as the Romans became acquainted, in the second century b.c., with the institutions providing rapid communication of intelligence and made use of them for other purposes. One of these instances is reported by Livy. When in 190 b.c. Scipio Africanus the Elder was planning to strike through Thrace at Antiochus III, the Seleucid king with whom the Romans were at war over the Dardanelles in Asia, he found it became imperative, first of all, to discover the intentions of Philip V of Macedonia. The king was, at that time, on friendly terms with Rome and so far had supported the Romans in their war with Antiochus. With his help the Romans had defeated the Syrian troops in 191 b.c. at Thermopylae and had driven Antiochus from Greece hack into Asia Minor. This was also in the interests of Macedonia but it was questionable whether Philip would agree to the passage of Roman troops through his territory. The attack against Antiochus on Asiatic soil could be made only if Philip remained friendly and cooperative. Livy relates (Bk. XXXVII. 7) how this important political and military intelligence was obtained:

![]()

68

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, by far the most energetic of the young men at the time, was chosen for this errand and, using relays of horses, with almost unbelievable speed, from Amphissa — for he was sent from there — on the third day reached Pella. The king was at a banquet and had gone far with his drinking; this very cheerfulness of mind relieved all anxiety that Philip planned to make any new trouble. And at that time the guest was graciously welcomed, and the next day he saw supplies in abundance prepared for the army, bridges built over the rivers, roads constructed where travel was difficult. Taking back this information with the same speed as on his journey thither, he met the consul at Thaumaci. From there the army, rejoicing to find its hopes surer and greater, reached Macedonia where everything was in readiness.

It is evident that, in this case, the young Roman messenger availed himself of the relay service instituted by the King of Macedonia. As he was an envoy to the king in a diplomatic affair, Macedonian authorities put the royal service at his disposal. Pella was the king’s residence, and Amphissa was situated near Thermopylae. The Romans must have been impressed by this service and, according to Livy, they admired its rapidity. But it seems that the Roman envoy did not travel with unusual speed. The distance of about 201 km. could be covered easily in three days with average speed as travelled by the Macedonian messengers when delivering routine intelligence. In spite of all this, we hear of no attempt on the part of the Romans to introduce anything similar under the Republic.

This is the more astonishing as there were statesmen in Rome who had fully grasped the importance of a reliable and speedy intelligence service in the conduct of state affairs. The most prominent among them, besides Scipio the Younger, was the celebrated Cato the Elder. This stern, energetic, and intelligent statesman was in some ways the incarnation of the old Roman Republican spirit, a valiant defender of Roman national traditions and an uncompromising opponent of the encroachment of the Greek culture on Roman and Latin intellectual life. But this Roman “isolationist” in cultural traditions was both an intelligent statesman and a good general, and he understood the importance of a rapid information service; he proved it himself upon one occasion. He was with the Roman army when campaigning against Antiochus in Greece and seems to have contributed by a courageous act of military intelligence to the great victory won at Thermopylae. The Roman Senate was following with anxiety the outcome of this encounter. Cato realized that it would be of great value, for his own political career as well, if he were able to inform the Senate as quickly as possible as to what occurred. Livy reports (Bk. XXXVI, 21) how he accomplished this,

![]()

69

and the report is interesting because it also gives us indications of the manner in which communications between Greece and Italy were made:

. . . the consul sent Marcus Cato to Rome, that from him, a thoroughly trustworthy source, the Senate and the Roman people might learn what had happened. From Creusa -this is the trading port of the Thespians, lying deep in the Corinthian Gulf—he made for Patrae in Achaea; from Patrae he skirted the shores of Aetolia and Arcanania right up to Corcyra and thence crossed to Hydruntum in Italy. On the fifth day from there in hurried progress by land he arrived in Rome. Entering the City before daybreak he went from the gate straight to the praetor Marcus Junius. Junius at daybreak summoned the Senate; Lucius Cornelius Scipio, who had been sent some days before by the consul, learning upon his arrival that Cato had reached ihere first and was in the Senate, came in while he was recounting what had happened.

This report is confirmed in the main by Plutarch in his Life of Cato the Elder (ch. 14), except that he gives another route by sea to Brundisium (Brindisi), instead of Hydruntum, from which Cato went in one day to Tarentum. reaching Rome in four days. From Livy’s account it is clear that Cato succeeded in arriving before the official messenger—it may not have been Cornelius Scipio — and deserved the distinction of being the first to report to the Senate.

Cato, as we shall see presently, also proved his interest in a better organization of the information service upon another occasion. Although we have seen that the principle of a good, rapid information service was appreciated by several prominent Roman statesmen during the Republican period, they were unable to overcome the apathy of the Senate and induce them to organize such a service in a more systematic way.

The envoys and messengers of the Senate were still using the old-fashioned system of requisitioning horses and other necessities for travelling in the cities through which they passed and which were Roman subjects or allies. The existence of this custom is evidenced by Cato’s report on his activity as praetor in Sardinia in 198 b.c., in one of his orations, preserved only in fragments (fragment II). He stresses that he never gave any such permission for the requisitioning of horses for travelling (he calls it evectio) to his friends for private purposes. This indicates that this custom must have been in force in Rome for a long period, and that it was sometimes abused by Republican officials for private purposes as well as for commercial and other journeys of their friends.

![]()

70

This means of transporting information was certainly not as rapid as the system used in the East. Requisitioning of horses and vehicles undoubtedly slowed down the journey of the officials concerned and was a burden on the cities and provinces, the more so as the evectio was often misused for private and lucrative purposes both by officials and their protégés.

Cato’s activity in Sardinia is mentioned also by Livy (Bk. XXXII, 27, of his History), who says that during Cato’s administration “the expenses which the allies were accustomed to incur for the comfort of the praetors were cut down or abolished.” By this Livy completes what Cato himself says. Livy’s report thus presents another piece of evidence confirming the fact that the Romans simply imposed upon their allies the burden of providing expenses for the information service of the Republic.

In another passage, Livy (Bk. XLII, 1) discloses additional details as to the origins of this custom and the manner in which this obligation became more and more onerous for both provinces and allies. When relating how Consul Postumius became angry in 178 b.c. at the allied city of Praeneste because it did nothing to facilitate his private voyage through its territory, Livy says, “. . . before he set out from Rome [he] sent a message to Praeneste to the effect that the magistrate should come out to meet him, that they should engage at public expense quarters for his entertainment, and that when he should leave there transport-animals should be in readiness. Before his consulship no one had ever put the allies to any trouble or expense in any respect.” Here Livy seems to exaggerate, because he himself mentions elsewhere, as we have seen, that the allies were expected to facilitate official voyages of the Republican magistrates. Then Livy explains how, at the beginning of the Republic, the state provided the magistrates with all things necessary for their official voyage, or — if we may rightly add — messengers sent out for necessary information:

Magistrates were supplied with mules and tents and all other military equipment, precisely in order that they might not give any such command [as did Postumius] to the allies. The senators generally had private relations of hospitality, which they generously and courteously cultivated, and their homes at Rome were open to the guests at whose houses they themselves were wont to lodge. Ambassadors who were sent on short notice to any place would call upon the towns through which their route took them, for one pack-animal each: no other expense did the allies incur in behalf of Roman officials. The anger of the consul, even if it was justifiable, should nevertheless not have found vent while he was in office, and

![]()

71

its silent acceptance by Praenestines, whether too modest or too fearful, established, as by an approved precedent, the right of magistrates to make demands of this sort, which grew more and more burdensome day by day.

Livy is right in relating how oppressive this service had become. He probably had in mind an abuse which had spread long before his time, which consisted in the Senate’s giving to some of its members from time to time a privilege of so-called free embassy — legatio libera — by virtue of which they were entitled to request from the allies every facility lor their voyage, even when undertaken only for private reasons. It is important to bear in mind this custom dating from the Republican period, as it became the basis of the further development of the official information service during the imperial period.

The Roman Senate found many opportunities to discover the unsatisfactory nature of this method of transporting embassies which were often the bearers of important intelligence. Much valuable time was lost in requisitioning, and more than once the embassies were late. Two incidents may be quoted which took place during the last Macedonian war with Philip V’s son, Perseus. Livy (Bk. XLIV, chs. 19, 20) reports that in March 168 b.c. the Senate awaited anxiously the return of a Roman embassy from Macedonia. Much depended on the nature of the intelligence they were bringing. They were not fortunate, however, for the stormy wind had forced them twice to turn back to Durazzo. At last they reached Brindisi on the Italian coast, but their journey from there to Rome lasted eight days. They could have done it easily in five.

The official delegation bringing the news of the final victory over Perseus at Pydna, won in September of the same year, took exactly three weeks to make the journey from Macedonia to Rome (Livy, Bk. XLIV, 45), although the unofficial announcement reached Rome in twelve days and was regarded as a record in rapid intelligence. But, from the subsequent book of Livy’s History, we gather that the intelligence of this victory had been transmitted to Africa sooner than to Rome. A few days after the news had reached Rome, the son of Masinissa, a Roman ally in Africa, came with congratulations from his father. The latter was able to give this instruction to his son by a special messenger who reached him just at the very moment he was embarking for Rome. This is another illustration of the slowness of Roman intelligence and of the superiority of the Africans in this respect.

![]()

72

For the transport of official letters containing information for the Senate and the magistrates in Rome, the magistrates in the provinces were bound to use special messengers called stcrtores, who were attached to their bureaus. We have very little evidence as to their functions, how they discharged their duties, or when they were first employed. But from the way in which Cicero, who in 51 b.c. was proconsul of Cilicia in Asia Minor, speaks of them in the letters written during the tenure of his office, we can conclude, however, that they must have existed for a considerable period and that their main function was to act as carriers of official information to Rome and to the magistrates of other provinces.

In the offices of the central magistrates the function of the provincial statores was occupied by the tabellarii, or letter bearers. These should be distinguished from the tabellarii employed by the publicani or tax collectors, whose letter bearers also exercised the function of modern tax collectors, and from letter bearers who were employed by private people, or who hired themselves out to individuals unable to afford their own letter hearer.

The letter bearers in official or private service were mostly slaves. They performed their duty on foot and, naturally, were expected to deliver the letters as quickly as possible. It seems to have been a hard job, making great demands on the physical endurance of the individual; and there was certainly no competition among the slaves for this doubtful honor. It is characteristic that the tribes which had supported Hannibal during his Italian campaign were, after their submission, as we read in Strabo’s Geography (Bk. V. 4.13), “appointed to serve the state as couriers and letter-carriers.” This was regarded as a punishment, a degradation from the military service in which they were engaged before their revolt, to the humble and difficult service of tabellarii. It seems strange that in the third century b.c., after the second Punic War, the information service was so little valued in Rome that to serve as tabellarius was regarded as degrading. On the other hand, this particular instance can be cited as proof that in the third century b.c. the need for numerous messengers to transport information from Sicily to Rome and back had increased considerably.

It seems, however, that this special class of Roman “civil servant” was slowly rising in the estimation of the Romans. It was realized that, besides physical capacity, certain moral and intellectual qualities were required of a good tabellarius, as the outcome of important political and military measures often depended upon the intelligent fulfillment of his mission.

![]()

73

We notice, therefore, that slaves or freedmen belonging to races regarded as intelligent, such as the Phoenicians, Greeks, Illyrians, and Gauls, were chosen for this function. Perhaps they acquired, at the end of this evolution, a kind of uniform. At least, in one of his letters (letter XV, 17.1) Cicero calls them petaseti, which expression seems to correspond to the Greek word pterophoroi which we find in Plutarch’s biography of Otho (ch. 4.1). This could indicate that the messengers wore feathers in their hats to identify themselves with Hermes, the divine messenger whose disciples and protégés they pretended to be. This would be quite suitable, as the speed reached by seasoned messengers was rather remarkable. From the study of Cicero’s rich correspondence, in which we often find meticulous details about the date a letter was expected or received, the average daily performance of a private tabellarius could be about 60-75 km. (37-47 miles).

We may suppose that the state tahellarii and the provincial statores were expected to give similar performances. But this is all; there is no trace, during the Republican period, of any organized information service.

The roads which the Romans had built were intended primarily for expediting the movement of troops. The messengers were bound to use them, of course, but no special provisions were made to facilitate their travel on the military roads, although their duties were important to the administration and for the security of the provinces as well as the whole state. In the second century b.c. there is only one instance which seems to suggest that a kind of postal and information service on the eastern model was developing. A Latin inscription from 132 b.c., commemorating the building of a road from Regia to Gapua, discloses that the magistrate who supervised the construction had put on the road not only milestones, indicating the distances, but also the tabelaarii. This wording was interpreted by A. M. Ramsay as evidence for the existence of a kind of postal service during the period of the Roman Republic. This, however, seems unproven. The evidence is too scanty, and one may rightly question the assumption that the word tabellarii used here in connection with miliarii, or milestone, and placed, so to speak, on the same footing, means in this context, messenger. It could be taken as a synonym of miliarii and mean an older kind of milestone, in the form of a tablet— tabula — on which written indications were placed. But, as the road was intended for military purposes, it would perhaps be more indicative to see in this special case the practical application of what Strabo had said about the degradation of some southern Italian tribes to tabellarii. The consul who constructed the road opened it also to State messengers travelling from Rome to Sicily.

![]()

74

The use of the tabellarii on the road, like its very construction, would have a military purpose. We cannot conclude from this slender evidence that the Romans had, during the Republican period, organized a postal information service, of the eastern type, in order to provide a more rapid transmission of intelligence.

2. Period of Civil Wars

A new period in the history of the Roman intelligence service opens towards the end of the Republic. In the first century b.c., Roman power had reached an unheard-of expansion on all sides. At that time Rome was already well on the way to world domination. Not only was Roman power firmly implanted in North Africa, Spain, and Gaul, but in the East Roman legions had advanced far on the road traced some centuries before by Alexander the Great. The protracted conflict with the Macedonians, under their kings Philip V and his son Perseus, ended finally in 168 b.c. with the destruction of the Macedonian Empire, the establishment of the Roman province of Macedonia, the extension of Roman influence over the Greek citystates federated in the so-called Athenian League, and finally in the complete submission of Greece. In Asia, the conflict with Antiochus III, former ally of Philip V and Hannibal, ended in the destruction of the Seleucid empire and the creation of two Roman provinces, that of Asia (129-126 b.c.) and that of Bithynia (74 b.c.). The conquest of the East was completed by the subjection of Syria in 64 b.c. and of Egypt in 30 b.c.

During the negotiations and fighting with the Macedonians and the easterners, the Romans had the opportunity of obtaining firsthand knowledge of the different systems of information services which had been established in Macedonia and the Eastern empires. With the advance of Roman troops conditions had changed and opportunities for a better information service were improved. The conquered lands were soon swarming with Roman merchants, land speculators, tax collectors, and agents of Roman financial magnates. It was, naturally, in their own interests to be well informed of the political situation in conquered or befriended lands and to report to the provincial magistrates any dangerous move likely to imperil their own and Roman interests.

That Roman traders might be at the same time intelligence agents was fully realized by the neighbors of Rome. Even in the early period, in 492-491 b.c., Roman buyers of corn from the southern

![]()

75

Italian tribes and from Sicily were suspected of being spies, treated with extreme caution, and were even in great danger of their lives, as is reported by the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Bk. VII, 2) and partly confirmed by Livy (Bk. II, 34). The Carthaginians were also very well aware of the fact that Roman merchants could be the most dangerous agents of Roman intelligence. Therefore, when concluding their peace treaties with Rome after the iirst and second Punic Wars, they took great precautions to eliminate such a danger. According to Polybius’s description (Bk. III, 22 ff.) of these first treaties, they contained a clause that sales could be concluded only “in the presence of a herald or town-clerk, and the price of whatever is sold in the presence of such shall be secured to the vendor by the state, if the sale takes place in Libya or Sardinia.” The presence of Roman traders beyond the Fair Promontory in Libya was not allowed. The second treaty was even more explicit: “No Roman shall . . . trade or found a city in Sardinia and Libya or remain in a Sardinian or Libyan port longer than is required for taking in provisions or repairing his ship. If he be driven there by stress of weather, he shall depart within five days. In the Carthaginian province of Sicily and at Carthage he may do and sell anything that is permitted to a citizen. A Carthaginian in Rome may do likewise.” The wording is interesting. It is clear that the Carthaginians, always well aware of the importance of intelligence, were doing their utmost to prevent the Romans from sending their agents into their country under the guise of traders. But, on the other hand, they succeeded in opening up to their own merchants and disguised agents free access to the Roman market.

The conquests in Asia Minor seem, more than any others, to have stirred Roman financiers, merchants, and speculators. The fabulous riches of the eastern empires attracted them, but in Asia Minor the situation was particularly delicate and tense. Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, the greatest enemy of Rome in the East, was disputing their conquests in Asia with considerable success. Again, following the example of ancient Persia from whence his ancestors came, not only did he count on a good fighting force in this struggle but also on good intelligence. He must have had his agents in Rome because he was always well informed as to the political situation in the city, at that time in the throes of civil war between the aristocratic and democratic parties. He learned of the sad fate of one of the best men Republican Rome had produced — Sertorius. A convinced but moderate democrat, Sertorius had proved that he possessed the highest qualities of an excellent general and a skillful diplomat.

![]()

76

But he was politically out-maneuvered in Rome by Sulla, who later became the leader of the aristocratic party. Sertorius was sent to Spain, where he continued fighting against the armies of his political opponents. He continued this struggle even after the democrats were ousted from power in Rome. Invited by the Lusitanians, a mighty Iberian tribe living in modern Portugal, to join them, he became their leader in the struggle with the armies sent by the new masters of Rome, his political opponents.

In spite of this, he remained an ardent Roman patriot and a convinced republican. His intention seems to have been to found an Ibero-Roman state in Spain, to conquer Italy and Rome from there, and restore democratic principles in Rome. Like Cato and Scipio he valued the importance of good intelligence and proved it when, at the beginning of his military career, fighting the Teutons who had invaded Gaul, he himself undertook “to spy out the enemy," as Plutarch says in his biography of Sertorius (ch. 3). “So putting on Celtic dress and acquiring the commonest expressions of that language for such conversation as might be necessary, he mingled with the barbarians; and after seeing or hearing what was necessary, he came back." This deed was so uncommon among the Romans that for it “he received a prize for valor.”

It may have been the pirates of the Cilician coast in Asia Minor who divulged the deeds of Sertorius in the East, as Sertorius was in touch with them, their fleet being at that time more powerful than that of the Republic, which had been greatly neglected during the civil wars. At least, this is suggested by a passage in his biography by Plutarch (ch. 23), where it is stated that “sailors from the west had filled the kingdom of Pontus full of tales about Sertorius, like so many foreign wares.” Mithridates decided to approach him and offer an alliance against the victorious party ruling in Rome, and an animated correspondence developed between the two men. We learn from Cicero’s second oration against Verres (chs. 86, 87) how these communications were transmitted. Verres was the most corrupt man of the period. His plundering of the provinces of Asia Minor which he had administered for several years caused great scandal in Republican Rome, accustomed though it was to such ugly affairs. It appears that Verres extorted from the city of Miletus not only valuable merchandise and costly entertainment, but, also, under the pretext of the right to the evectio in official voyage, one of their best cruisers for his journey to Myndus. Upon his arrival, instead of returning the cruiser, he ordered the sailors to return by land to their city and sold the cruiser to two intelligence agents entrusted by Mithridates with carrying messages to Spain.

![]()

77

The Miletians were famous for the solidity and swiftness of their naval constructions; they needed such vessels for their dangerous mission and were willing to pay the price.

We learn further from Appian’s description of the wars with Mithridates (Bk. XII, chs. 26, 79J that the king made frequent use of fire signals and of advanced posts signalling intelligence by relays on the movement of enemy troops. How well Mithridates controlled the highly efficient intelligence service in his lands was demonstrated by the massacres of Roman merchants and other Roman citizens who entered Asia Minor for business and other purposes. Mithridates, well informed about the endless dissensions in Rome and the progress of the civil war. chose his moment well for the subordination of the whole of Asia Minor to his rule. Well acquainted with the activities of the Roman citizens in the country, and aware of their unpopularity among the native populace, he decided, first of all, to rid himself on one day of all possible fifth columnists who feigned friendship with him, and who at the same time would send intelligence to the enemy to sabotage his war plans.

He made his arrangements thoroughly and with oriental cruelty, as Appian (Bk. XII, 22) describes it:

Mithridates . . . wrote secretly to all his satraps and city governors that on the thirtieth day thereafter they should set upon all Romans and Italians in their towns, and upon their wives and children and their freedmen of Italian birth, kill them and throw their bodies out unburied. ... He threatened to punish any who should bury the dead or conceal the living, and proclaimed rewards to informers and to those who should kill persons in hiding. To slaves who killed or betrayed their masters he offered freedom, to debtors, who did the same thing to their creditors, the remission of half their debt. These secret orders Mithridates sent to all the cities at the same time. When the appointed day came disasters of the most varied kinds occurred throughout Asia. . . .

Appian then goes on to describe the frightful scenes which were witnessed in the main cities of Asia Minor. This happened in 88 b.c. The number of Romans killed on one day is estimated at eighty thousand to one hundred thousand people.

When in 66 b.c., after long years of wars in Asia Minor with varying degrees of success, the people demanded that the liquidation of the worst enemy of the Romans in Asia be entrusted to Pompey, the new star in the political and military firmament of Rome, Cicero pronounced his famous speech in the Senate on the “Appointment of Gnaeus Pompeius.”

![]()

78

Cicero (ch. 3) described this massacre in the following words, which express at the same time the admiration felt by Romans for the efficiency of the eastern intelligence service:

I call upon you to wipe out that stain incurred in the first Mithridatic war, which is now so deeply ingrained and has so long been left upon the honor of the Roman people: in that he who, upon o single day throughout the ivhole of Asia and in many states, by a single message and by one dispatch marked out our citizens for butchery and slaughter, has hitherto not only failed to pay any penalty adequate to his crime but has remained on the throne for two and twenty years from that date.

This speech is interesting also in another respect. In the preceding chapter Cicero testifies that the massacre of so many Roman merchants and agents did not deter others from venturing into the land which at that time was regarded in Rome as fabulously rich. Scarcely had the Romans reconquered some of the Asiatic provinces than new crowds of traders, speculators, and publicans (tax collectors) settled there. It was these men who gathered their own intelligence on the plans of Mithridates who, at that time, was in alliance with the Armenian King Tigranes. Because it was in their own interests, they also found ways to transmit their information to Rome. In numerous letters to their representatives and senators they pressed for decisive action. Here is Cicero’s exclamation:

Every day letters arrive from Asia for my good friends the Roman knights who are concerned for the great sums they have invested in the farming of your revenues; on the strength of my close connection with that order they have represented to me the position of the public interests and the danger of their private fortunes.