8. The Russia of Kiev

1. The Eastern Slavs, the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars

2. Scandinavians discover the river route from the Baltic to the Near East

4. Discovery of the route from the Baltic to Constantinople; Norsemen and Slavic confederates

5. Askold and Dir of Kiev accept Christianity

6. Oleg, founder of the Russian State; Commercial treaties with Byzantium

7. Baptism of Olga, her relations with Byzantium and Germany

9. Vladimir and Byzantine Christianity

10. Roman or Bulgarian origin of the Russian hierarchy?

1. Commercial intercourse between East and West the basis of Kiev’s greatness

5. The Bulgarian and Moravian literary legacy

III. Kiev, the principalities, the West and Byzantium

1. Literary relationship between Bohemia and Kiev

2. The Cult of Western saints in Kiev

3. Religious contact between Kiev, Germany and Bohemia after the schism

4. The Kievan State and Western Europe

5. Kiev’s relations with the Byzantine Emperor

6. Kiev, an intermediary between Byzantium and the West? Lost possibilities

7. Western influences in Galicia, Volynia and Novgorod

8. The Principality of Suzdal, and expansion towards the east

(I.)

(1)

Before the problems connected with the formation and development of the mighty political organization of the Eastern Slavs centering in the city of Kiev are surveyed, the political, cultural and racial situation in the eastern territories occupied by the Slavs must be examined. Successive waves of invaders had

![]()

190

followed one another across the steppes of southern Russia — Scythians, Sarmatians, Goths, Huns, Turkic Bulgars, Avars, and Khazars. Each of these invasions left its mark on the lands over which it rolled, a mark which could not be ignored by the Slavic tribes which had made it clear from the beginning of their penetration eastwards that they intended to stay there for good. Then the sudden appearance of the Huns came as a warning, a red light for the whole of Eastern Europe, indicating that from the human reservoir in the Asiatic steppes, teeming with fierce, nomadic tribes, a new deluge might at any time sweep over the grassy plains of southern Russia and submerge all Central Europe. Two of the floods of invaders which followed were particularly dangerous, not because of their dynamic fierceness, but because they had stopped on the fringes of the Slavic lands and because the peoples which these great waves from Asia brought with them settled securely on the boundaries of the Slav territories at a time when the Slavic masses had not yet found a strong form of leadership. The two peoples concerned were the Bulgars and the Khazars. As has been related the Turkic Bulgars had settled on the middle Volga and the Kama river and different branches of that nation extended their sway over the Russian steppes as far as the Danube. Their empire suffered a serious setback when the Avars appeared; but the Avar invasion removed the danger which threatened Central Europe from the Bulgars. Like all other invaders from Asia, the Bulgars pressed instinctively towards the frontiers of the Roman Empire. Indeed, a section of the Bulgars not only reached the Danube but, with the eventual help of the Slavs, founded a solid state in Macedonia and Thrace, that had once been flourishing imperial provinces.

The Bulgars who had established themselves on the Volga consolidated their state and soon a prosperous era opened for them. It was to be expected that their expansion from the Volga would be directed westwards into the lands which the Slavs were gradually occupying.

The Khazars, of the Turkic linguistic family, after establishing themselves in the Caucasus region in the second half of the seventh

![]()

191

century, were destined to play an even more important role among the Eastern Slavs than the Bulgars had done. They replaced the Avars as overlords of the Slavs on the Dnieper, and Kiev became the western outpost of their empire, the center of which was transferred, some time after the year 720, to ltd on the Volga delta.

The danger which threatened the Slavs from these two Turkic empires was the more pressing in that neither the Volga Bulgars nor the Khazars were totally lacking in culture. Each had a close relationship with the empire of Bagdad, where the Abbasid dynasty of khalifs had brought the power of the Arabs to new heights. Art and culture flourished at the court of Bagdad and the influence of this Arab renaissance was felt as far as Constantinople, especially in the first half of the ninth century. The Caspian Sea and the Volga river gave the Arabs easy access to the interior of modern Russia and even to the Baltic coast. These waterways were also a channel for Islamic propaganda among the Turkic tribes there. This propaganda was, indeed, so successful that the Volga Bulgars embraced the religion of Mohammed, probably during the ninth and early tenth centuries. Islam also penetrated into Khazaria and it is said that in the ninth century the khagan of the Khazars lent an ear to Christian, Jewish and Mohammedan missionaries alike.

Here was a serious danger for the whole of Europe. Had the Islamic civilization from Khazaria and Bulgaria reached the pagan Slavic tribes, which were drawing nearer and nearer to the Volga and the lower Don, the frontiers of Europe would have been fixed somewhere on the Carpathian Mountains. At this time, Russia was on the verge of becoming a part of the Moslem world of Asia.

The danger was averted thanks to a new factor which entered the Eastern Slavic scene: the appearance of the Scandinavians and the Byzantines. The Scandinavians came first, making their appearance among the Eastern Slavic tribes just in time to weld them into a firm political bloc, which proved able to withstand and obstruct the westward rush of the Asiatic hordes and even to

![]()

192

contribute in the long run, thanks to the intervention of Byzantium, to the expansion of European civilization eastward, far beyond the Volga and the Ural Mountains.

The appearance of the Scandinavians on the Baltic shore and in the interior of modern Russia is only one of the exploits of the daring sons of the fabulous Scanza in the ninth and tenth centuries. They regarded the whole continent of Europe as a field to be exploited and colonized. The deeds of the Danes and Norsemen in Frisia, in the valleys of the Seine and Loire, in Normandy and England, in Ireland and the isles of the North Atlantic, and those of the Swedes and Norwegians among the Finns in the Baltic region and among their Slavic neighbors — all these represented the last wave of the Germanic migratory movement. The settlement of the Scandinavians among the Eastern Slavs was destined to become one of the most important and decisive events among the achievements of the Germanic migratory period.

The story of their advent among the Slavs is long and fascinating and many details of it are still hotly debated by specialists. Their explorations along the east coast of the Baltic brought them into contact with the Baltic and Finnish populations settled there. Through these peoples they heard of the existence of two flourishing empires on the Volga and of the brisk trade which the Khazars were carrying on with the Arabs of Bagdad. It was not difficult to discover the easy artery provided by the Volga for these commercial transactions. In the second half of the eighth century, if not earlier, the Scandinavians were on the middle Volga. Direct relations between Swedes and Khazars began about 800. The discovery of the Volga route was most probably made, not from the Gulf of Riga and the provinces of Dvinsk, Vitebsk, Kovno and Pskov, where little evidence of Scandinavian occupation has been found, but from the Gulf of Finland which offered an easy access to the Volga via Lake Ladoga and Beloozero and where it was a comparatively simple matter for them to haul their boats

![]()

193

over the portage. There was another route from Ladoga via Lake Ilmen, which the Slavs had already reached in the ninth century. [1] The country between Ilmen, the Volkhov river and Ladoga is apparently the wooded and marshy island on which some Arab writers located the original habitat of the “Rus.” On these routes, two important Scandinavian colonies were founded — Beloozero and Novgorod, their establishment being attributed to Rurik (Roersk) and his brothers.

How can the sudden interest of the Norsemen in commercial intercourse with the Eastern world be explained? Here we must return to those facts which H. Pirenne attempted to set down more or less convincingly. [2] Trade with the Levant had become indispensable to Western Europe ever since Roman civilization had reached it. The products of the Near East used to find their way to the West by way of the Mediterranean; but the Arab conquest of the Near East, North Africa, Sicily, Spain and a part of southern Italy drastically changed the situation. The Arabs then had control over this easy maritime route between the Near East and the West. Moreover the consumption of eastern spices and other luxury merchandise in the Arab empire grew in direct ratio to the increasing refinement of its civilization. This left little of these wares over for export to the West. Furthermore in the ninth century Arab pirates made sea communications between the East, Byzantium and the West almost impossible. There was an urgent need to find new routes to the Orient and it was this which encouraged the Norsemen in their exploration of the eastern end of the Baltic Sea. The memory of commercial intercourse between the Baltic, the Crimea and the Near East was

1. Besides archaeological evidence — gathered by T. J. Ame, La Suède et L’Orient (Stockholm, 1914) — important philological material allows us to trace the presence of the Norsemen on the Baltic and on the Volga and the Dnieper with precision. See for details, M. Vasmer “Wikingerspuren in Russland” (Sitzungsberichte d. Preus. Ak. Phil. Hist. Kl., Berlin, 1931). Vasmer’s findings also show that the Volga route was discovered first.

2. In his book Mohammed and Charlemagne (London, 1940). See above page 44. Cf. especially the criticism of Pirenne’s theories made by R. S. Lopez ("Mohammed and Charlemagne: a Revision,” Speculum XVIII [1943], pp. 14-38).

![]()

194

still fresh in the minds of the peoples on the Baltic coast and by following up these clues the Norsemen found a new way by which the Near Eastern countries could be reached.

The native population found a strange name for the newcomers and many theories have been advanced to explain how it came about that they were called Rus — Russians. The most plausible theory is that the origin of Russia’s name comes from the Scandinavians themselves and the Finns. Certainly the name shows an affinity with the Old Swedish word rodi or rodhsi — in modern Swedish, ro, ros and rod — meaning “rowing” or “sculling.” There is a part of Sweden — probably the first part with which the Finns became acquainted — which is called “Roslagen,” or in older documents “Rodslagen” and it is natural to suppose that the first Swedes to come into contact with the Finns came from this part of Sweden. The Swedes are still called “Ruotsi” by the Finns and “Rootsi” by the Estonians; and it was this name which was apparently given by the Finns to the first Swedish settlers amongst them. The Slavs have transformed the name, according to their phonetic pattern, probably as early as the eighth century, into Rus, Rusi. The Byzantine form, Rhôs, is possibly an adaptation from the Septuagint version of the Holy Scriptures, where, in the prophecy of Ezekiel, a people called Rhos is erroneously mentioned. [1]

The Norsemen soon became well known on the Volga, among the Bulgars and in Khazaria, and they ventured across the Caspian Sea and reached Bagdad. Rich finds of Arab coins in

1. The Norsemen were also called Varyagi by the Slavs and Varangoi by the Byzantines. The word is a Slavic derivation from the Nordic, vaering, varing, denoting a member of a kind of brotherhood formed by a number of the Norsemen for a military expedition or commercial enterprise. The men forming the brotherhood — družina in Slavic — were bound to each other by a special oath. Cf. also what H. Paszkiewicz (The Origin of Russia [London, 1954] pp. 1-25, 107-132) says on the origin and meaning of the word "Rus.”

![]()

195

Sweden and on the Baltic coast still testify to the lively commercial intercourse which was carried on between Scandinavia, the Baltic countries and Bagdad.

But of even greater significance for the future was the Norsemen’s discovery of a route from Novgorod via the Dnieper and the Black Sea, to Constantinople. The region of the upper and middle Dnieper was already a Slavic country when the Norsemen reached it; but commercial traffic on the river was controlled by the Khazars, masters of the Dnieper Slavs and of Kiev, its important trading center. A strong detachment of Norsemen, led by Askold and Dir, reached Kiev (c. 856-860), and as the Khazars were unable to provide the Slavs with adequate protection against bands of nomads marauding in southern Russia — the presence in the ninth century of the Magyars amongst others is proven — the Poljane or Slavs of Kiev and the middle Dnieper welcomed the newcomers and willingly accepted them as overlords in place of the Khazars. Constantine Porphyrogennetus gives some important details, in his book on the administration of the Empire, concerning the kind of relationship which existed between the Slavs and the Norsemen. On two occasions he refers to the Rhôs and their Slavic ’’confederates." This clearly indicates that the occupation by the Norsemen of various Slavic settlements was not carried out by force, but that in many cases the Slavs accepted the Scandinavians and concluded protective treaties with them.

In this way, the Norsemen took over control of the trade between the Baltic and the Black Sea as successors of the Scythians, the Sarmatians and the Khazars. There were still Greek cities in the Crimea, now under Byzantium, and numerous settlements of Jewish merchants, which had survived for many centuries. Their citizens still made their living by trading with Byzantium, Asia Minor, the Near East and the interior of modern Russia; but the Norsemen were not content to deal only with the Greeks of

![]()

196

the Crimea. Peaceful trading had revealed to them the wealth of Constantinople, and with their Slavic subjects and confederates they formed a bold plan to seize these treasures by a surprise attack.

In the early summer of 860, when the Emperor Michael III and his uncle Bardas were leading an expedition against the Arabs in Asia Minor, a large fleet manned by hitherto unknown barbarian invaders appeared before Constantinople, having laid waste the shores of the Black Sea. The city “protected by God” went through some exciting moments while it watched the newcomers burning the suburbs and preparing their final assault from the sea. But Byzantium was saved even before the Emperor and his fleet, summoned in the nick of time by the commander of the city and the Patriarch Photius, had returned. The danger had been so great, however, that future generations were wont to speak of the miraculous intervention of Our Lady brought about by the prayers of the holy Patriarch.

This first Russian attack upon Constantinople had great consequences for the subsequent history of the Eastern Slavs. In order to protect themselves against another surprise of this kind, the Byzantines hastened to strengthen their friendship with the Khazars. The embassy which was dispatched to Khazaria via the Crimea for this purpose was headed by Constantine and Methodius, the future apostles of the Slavs. From the Vita Constantini valuable details may be learned concerning the nations inhabiting the Crimea and the religious propaganda carried on among the Khazars by Jews, Christians and Mohammedans. [1]

1. It is known that the khagan of the Khazars and many of his subjects had yielded to the Jewish propaganda coming mainly from the numerous Jewish colonies in the Crimea. They accepted the Jewish creed — the first case of a large part of one nation becoming Jewish at such a late period. The Khazars were otherwise a very tolerant nation. They are probably to some extent the ancestors of the eastern Jews. Driven by the Cumans and the Mongols from their homeland, many of the Jewish Khazars were settled in Poland by the Polish kings. There they mixed with western Jews. On the conversion of the Khazars, see F. Dvornik, Les Légendes de Constantin et Méthode vues de Byzance (Prague, 1933), pp. 148 ff. A complete bibliography on the Khazars to the year 1933 will be found in this book. A more recent critical bibliography has been compiled by A. Zajączkowski in “Ze studiów nad zagadnieniem Chazarskim” (Studies on the Khazar problem), published in the Memoirs of the Oriental Commission of the Polish Academy (No. 30, Cracow, 1947), with a résumé in French. The author thinks that the letters of Khazar history allegedly from the tenth century are apocryphal, probably dating from the twelfth century, but that they are based upon a national Jewish tradition. Their compiler used quite precise geographical and historical information given by Islamic writers. They are documents which are not to be neglected. On the fate of the Khazars after the eleventh century see H. von Kutschera, Die Chazaren (Vienna, 1909), pp. 162 ff.

![]()

197

The sealing of the friendship between Byzantium and the Khazars had its effect upon the Russian Slavs of Kiev. They soon yielded to the cultural influence coming from Byzantium and asked to be baptized and the Patriarch Photius had the satisfaction of sending missionaries to them and of establishing, some time about the year 864, a bishopric at Kiev. This first phase of Christianity did not last very long. About 878-882, Kiev was conquered by the Russian Prince Oleg (Helgi), who came from Novgorod. The Russians and the Slavs under his sovereignty were, naturally, pagan and they were bitterly jealous of the prosperity of the colony at Kiev. Because of this, Christianity in Kiev was quickly exterminated.

This was a great pity, for the whole future of Russia would undoubtedly have developed very differently had Christianity survived in Kiev. It was at that time that other Slavic nations, the Moravians and the Bulgars, were being won for the Christian faith by Byzantium but Russia had to wait another hundred years before becoming a Christian country.

Oleg is the real founder of the Russian state. It was he who united North and South in one political unit and from Kiev brought almost all the eastern tribes under his sovereignty. He

![]()

198

conquered the Drevljane about 883, the Severjane in 884 and the Radimiči in 885. He put a definite end to Khazar supremacy over the Slavic tribes and protected his subjects effectively against enemy incursions. He also inaugurated a period of friendly relations with the Byzantines which may have occurred after a more or less successful show of force during the second Russian attack on Constantinople in 907. [1] His new state received a kind of international recognition in 911 with the conclusion of a commercial treaty with Byzantium.

Oleg also applied his statesmanship successfully to the task of fusing the Scandinavian upper class with the Slavic elements and his name therefore deserves to rank with those of two other great Norse conquerors who altered the course of European history — William the Conqueror and Robert Guiscard.

There was a temporary rift in the good relations between the Russians and the Byzantines during the reign of Oleg’s successor Igor’ (Ingvar), who organized an expedition against Constantinople in 941. The Russian Primary Chronicle describes the attack, which ended in disaster for the Russians. The same source refers to another expedition which led in 944 to the conclusion of a further commercial treaty but the report of the chronicler should be read with caution. One thing does appear to be clear, however: that peaceful relations between Igor, and the Byzantines were restored, and that the Russian Prince renewed the commercial treaty concluded by his predecessor. But if the text of this new treaty, as given in the Russian Primary Chronicle is compared with that of the old one, [2] it becomes clear that the rights of the Russian merchants were curtailed because of Igor’s defeat by the Byzantines. There is no provision in Igor’s treaty for the

1. The historical authenticity of this attack, recorded in detail in the Russian Primary Chronicle, is still questioned by many specialists. For details and bibliographical notices see A. Vasiliev, “The Second Russian Attack upon Constantinople," published in Dumbarton Oaks Papers VI (1952), pp. 161-225.

2. A new edition of the text of the Russo-Byzantine treaties was published, with commentaries and bibliographical data by A. A. Zimin in Pamjatniki prava Kievskago gosudarstva (Legal documents of the Kievan State) I (Moscow, 1952), pp. 1-70.

![]()

199

Russian merchants to be excused from customs duties, nor, under this treaty, were the Russian traders allowed to move about freely on Byzantine territory. The Russians had to promise to repatriate slaves escaping from Greece and were prohibited from intervening in affairs concerning Byzantine possessions in the Crimea. They were allowed to fish near the mouth of the Dnieper; but were denied permission to spend the winter there. Both treaties give a very impressive picture of social and economic conditions in Kievan Russia and show that trade with Byzantium was the main source of the steady economic and cultural progress of that state. It seemed that the Scandinavians had at last found the new way to the riches of Byzantium and the Near East, the way which Western Europe had been seeking since the Arabs had obtained control over the maritime routes in the Mediterranean Sea.

It was Igor’s widow, Olga (Helga), who took over the regency after his death in 945, during the minority of their son Svjatoslav. She first of all crushed the revolt of the Drevljane, who were responsible for the death of her husband. Olga enforced the unity of her vast realm and through wise administration strengthened its economic basis. This energetic and intelligent woman quickly realized the importance of Byzantium to Russian progress and she decided to link her country even more closely with the Empire by introducing Christianity into the regions over which she ruled. It was only to be expected that friendly intercourse between Russia and Byzantium would prepare the way for the penetration of Christianity into Russia. We learn from the Primary Chronicle that in 945 there was a church of St. Elias in Kiev, where the Russian Christians confirmed by oath their resolve to abide by the stipulations of the commercial treaty with Byzantium. This Christian community had grown up on the ruins of the first Christian center, which had been destroyed when Kiev was conquered by Oleg. It consisted mainly of Russian

![]()

200

traders who had become acquainted with the Christian religion when they were quartered near the church of St. Mammas in Constantinople. It was in this small Kievan center that Olga first encountered Christianity, and it would thus be quite natural to suppose that she herself was baptized there. According to the old Russian tradition, preserved in the Primary Chronicle, however, she went to Constantinople for this rite. It is known that her voyage to Constantinople in 957 is an historical fact, because her reception there was described in some detail by Constantine Porphyrogennetus in his Book of Ceremonies.

Specialists in early Russian history still debate whether this traditional story should be accepted. Most of them have decided that Kiev was the place of her baptism, arguing that the imperial writer describes only Olga’s reception and not her baptism and that the Russian chronicler places her baptism in the year 955, that is, two years before her visit to Constantinople. In spite of these views, the tradition of the Primary Chronicle should not be lightly dismissed. The chronicler’s dates for this period are generally regarded as unreliable and should not therefore be quoted as an argument. As for Constantine Porphyrogennetus, he described in his Book of Ceremonies only those events which were likely to recur at the court of Constantinople. It could well be expected that another Russian prince might visit the city, and the masters of ceremonies were therefore given a record of all the details to be observed on such an occasion, were it to be repeated. But it could hardly be taken as likely that Russian princes, once Christianity had been accepted in their country, would make a habit of visiting Constantinople in order to be baptized. Therefore, Constantine limited himself to describing only the ceremonies performed during Olga’s reception at the court.

Moreover, Olga’s baptism in Constantinople is also mentioned in the Byzantine chronicle of Cedrenus, which was based on that of Scylitzes, not yet published, and by the continuator of the Latin Chronicle of Regino. Tin’s last source is important. The report in it was written by the German envoy to Kiev, of whom more will be heard presently, and should thus give a true impression of

![]()

201

Kiev in the tenth century. We should, therefore, date Olgas baptism in the year 957 and place it, not in Kiev, but in Constantinople. One thing cannot be contested: that Olga’s conversion was the work of the Byzantine missionaries who administered the church of St. Elias in Kiev. The fact that Olga received the baptismal name of Helen, which was the name of the Byzantine empress who was her godmother, also points to the conclusion that the Byzantines were responsible for her conversion.

But how is Olga’s action in requesting Otto I of Germany to send a bishop to Kiev to be explained? This fact is reported by the continuator of the Chronicle of Regino, most probably Adalbert, the very bishop whom Otto sent at Olga’s request. This has seemed so extraordinary to many Russian historians that they simply refused to admit the authenticity of the annals which reported it. It can, however, be quite easily explained. We can see here that Olga’s bold action in accepting Christianity did not apparently win the unanimous approval of the Russian aristocracy. The Scandinavian boyars were suspicious of Byzantium’s political and religious influence. Many of them still remembered Igor’s expedition against Byzantium, on which they had accompanied him, and they could not reconcile themselves to the sudden change brought about by his widow. Olga tried to allay their apprehensions and to neutralize Byzantine influence by forging a closer link with the mighty German king, whose deeds against the Magyars had won him great respect in the eyes of the fierce Scandinavian warriors at Olga’s court. There is no need to suppose that Byzantium had refused the new convert an independent religious organization and that she had therefore turned to the German ruler to obtain it. In fact, there is no evidence to support such a theory.

Olga’s request appeared to Otto as a godsend, for he dreamed of making Magdeburg into a mighty metropolis for all the Slavic lands in the East and his plan seemed to be well on the way to realization. He sent Bishop Adalbert to Kiev; but a great disappointment awaited him. Probably even before Otto’s envoy had reached Kiev, Olga had been forced to hand over all effective

![]()

202

authority to her son Svjatoslav, who had no use for either Byzantine or Western Christianity. This is fresh proof of the strong anti-Christian reaction in his Kievan retinue.

Svjatoslav (964-972), the first Norse ruler of Kiev to be known only under a Slavic name, [1] was a true Viking at heart, adventurous, reckless, courageous and mainly interested in battle and booty. This is the conventional picture of Svjatoslav drawn by most historians. Recently, however, Russian historians have tried to portray Svjatoslav in brighter colors. B. D. Grekov, [2] for example, sees in him not only a great warrior but also a ruler of international renown, who by his deeds profoundly influenced the history of the Moslem world and of Byzantium.

It must be acknowledged that Svjatoslav gave proof of considerable political vision when concentrating his efforts at the beginning of his reign on Russian expansion towards the East. It is difficult to establish the exact dates of Svjatoslav’s eastern campaigning, as the information given in the Russian Primary Chronicle and by the Arab writer Ibn Haukal is slightly confused. One of the results of Svjatoslav’s expeditions was the subjugation of the Vjatiči, the last Slavic tribe still subject to the Khazar khagans. Thus, the unification of all Eastern Slavs in one empire was completed. Svjatoslav’s lasting achievement was the destruction of the Khazar empire, brought about probably in two campaigns (963 and 968-?), and instead of the Khazars the Russians of Kiev became the masters of the Ossetians in the lower Don Basin and of the Circassians in the Kuban area. Svjatoslav saw, however, clearly that, if he wanted to rid his realm for good of the Khazar danger, it was imperative for him to control the middle and lower Volga and this led him to an expedition against

1. He seems to have had a Scandinavian name also. A. Stender-Peterson, “Die Varägersage als Quelle der altruss. Chronik,” Acta Jutlandica VI (1934), p. 15 thinks that Svjatoslav’s Scandinavian name was Sveinald.

2. In his work, Kievskaja Rus (The Russia of Kiev) (Moscow, 1944, 4th ed.), pp. 263 ff.

![]()

203

the Volga Bulgars. Probably about the year 965 he broke their resistance and sacked their capital Bulgar. This finally sealed the fate of the Khazar empire and Svjatoslav’s troops looted the Khazar capital Itil.

For the first time Russia extended its domination to the Volga, the Caspian Sea and towards the Caucasus and it seems that Svjatoslav’s influence was also strongly felt in the Crimea. All this was a great success which might have become decisive for Russia and Europe, because in the middle Volga among the Bulgars and in Itil the Russians came into direct contact with Islam. When it is recalled what a profound impression Svjatoslav’s victories had made on the contemporary Moslem world — Ibn Haukal testifies to that — it can be imagined that the Arabs would have made a great effort to win over this new and powerful ruler. For Moslem missionaries had succeeded in converting the Bulgars and in penetrating into Khazaria. As the Varyags and their Slavs were still pagans, there was a danger that the fascinating civilization of the khalifs might outshine that of Byzantium and that instead of Christianity in either the eastern or the western form, Islam would have crossed the Volga, the Dnieper and the Dniester to take firm root on Russian soil. Had this happened, it might then have crossed the Carpathian Mountains to find a warm reception among the nomad Magyars.

The danger was averted by the Byzantines, who persuaded Svjatoslav to march against the Danubian Bulgars. Here the prince showed his adventurous nature; for instead of consolidating his new conquests in the east, as would seem logical to any statesman, he accepted the offer from Byzantium. Perhaps the secret hope that once firmly established in Bulgaria he could realize the dream of his predecessors — to conquer Constantinople — influenced his decision.

There is some evidence to indicate that Svjatoslav had far-reaching plans once he was established in the eastern part of Bulgaria. The Russian Primary Chronicle attributes to Svjatoslav the intention of transferring his residence from Kiev to Perejaslavec (Little Preslav) in Bulgaria:

"Svjatoslav announced to his

![]()

204

mother and boyars, ’I do not care to remain in Kiev, but should prefer to live in Perejaslavec on the Danube, since that is the center of my realm, where all riches are concentrated, — gold, silks, wine and various fruits from Greece, silver and horses from Hungary and Bohemia, and from Rus furs, wax, honey and slaves.’ ”

This is an interesting declaration. If it can be taken at its face value, then we have to conclude that Svjatoslav planned to found a great Slavic empire which would comprise not only Kievan Russia but also a great part of the Balkans. The reaction of the Byzantines shows that they were well aware of the new danger and when the Pecheneg diversion engineered by them failed to deter Svjatoslav from reentering Bulgaria, the Byzantines concentrated all their efforts against the Russian Prince. After defeating him, they annexed Eastern Bulgaria and Svjatoslav’s imperial dreams were shattered for ever. All that he got out of his Bulgarian adventure was a new commercial treaty with Byzantium. On his way home he met his death at the hands of the new invaders of southern Russia, the Pechenegs (Patzinaks). [1]

The fate of the Kievan State was finally decided by Vladimir (Volodimer, Valdimar?) (c. 980-1015), Svjatoslav s son. After fleeing from Novgorod to Sweden, Vladimir defeated his brother Jaropolk of Kiev with the help of a detachment of Norsemen, whom he brought from there. Vladimir then consolidated the State by once more uniting Novgorod with Kiev and affirming his authority over some recalcitrant tribes — the Vjatiči and the Radimiči. He then opened a new gate to the West by adding to his realm the Red cities and Přemysl, territories which formerly had been part of White Croatia, and had then been occupied by the founder of the Polish State, Mieszko I.

Vladimir’s most important act was the introduction of Christianity

1. See above, page 140.

![]()

205

into Russia, and the Russian Primary Chronicle gives a vivid account of his conversion. According to this, he was solicited by the Mohammedan Bulgars, the Jewish Khazars, the Germans representing the Pope, and the Byzantines, each of them pressing him to embrace their respective religion. Then Vladimir decided to send envoys to the different countries to investigate their religious practices and faiths. His representatives showed no enthusiasm for the religions of the Bulgars, the Khazars or the Germans; but when they came to the Greeks, they were full of admiration. “We knew not,” they confessed, “whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it . . . We cannot forget that beauty.” On the strength of their report, Vladimir decided to accept the Greek version of Christianity.

The account is, of course, legendary; but it reflects certain historical facts. It shows first of all that the Mohammedan danger from the Bulgars, which we mentioned above, was a reality. This influence is moreover attested by archaeological finds showing that Arab culture penetrated into Kievan Russia in its early history.

Secondly, it is known that Jewish influence in southern Russia grew stronger after the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism. It was natural for Jewish merchants to be interested in such an important commercial center and a Jewish colony certainly existed in Kiev. Mention also of the Germans in the account above may be an echo of the short episode of Olga’s reign, but the stress laid by the chronicler on Byzantine propaganda and on the deep impression made by the Byzantine liturgy reflects the prolonged peaceful penetration of Greek Christianity into Russia from Askold’s and Igor’’s times.

The Russian chronicler goes on to describe how Vladimir was baptized by the Bishop of Kherson, a city which he had conquered from the Greeks when he realized that they were delaying the fulfillment of their promise to send him a Byzantine princess, “born in the purple,” for a wife.

The facts reported by the Russian chronicler — that Vladimir

![]()

206

was baptized by the Greeks and that the organization of the Russian Church was the work of Byzantium — are questioned by some scholars who believe that the baptism was carried out by Scandinavian missionaries and that the establishment of the Russian hierarchy was due to the initiative of Rome. Others think that credit should be given to the Danubian Bulgars and the Patriarch of Ochrida.

The defenders of the Scandinavian theory think that Scandinavian priests had acquainted Vladimir with the principles of Christianity and that Olaf Tryggvason finally prevailed upon him to embrace the Christian faith. But it is well known that Christianity made very slow progress in Novgorod, where the Scandinavian influence was most marked, and it is to be expected that if the Scandinavians had shown such a missionary zeal their work would have left its deepest impression there. Olaf Tryggvason was in close contact with Vladimir; but his Christian influence should not be overrated. Before he recovered his throne in Norway, this Scandinavian hero was far more interested in plundering the British Isles than in preaching the Christian faith in Russia. We have no evidence that the Scandinavians, who had only recently been converted to Christianity and who certainly did not have a superabundance of priests, had developed any missionary activity at such an early stage.

Moreover, it appears that the Scandinavians were under a strong influence from Byzantine civilization. The names of the merchants mentioned in the Russo-Byzantine treaties are all Scandinavian. Trade with Byzantium was thus in their hands and most of the Russian merchants living in the quarter of St. Mammas in Constantinople were Scandinavians. They were touched by Byzantine religious propaganda. We have thus to admit that the Scandinavians were mainly responsible for the spread of Byzantine civilization and religion in the Kievan state. [1]

1. Cf., for example, what A. Stender-Peterson (Die Varägersage, op. cit., pp. 84 ff., 120 ff., 237 ff.) says about strong Byzantine influences on the origin of some Scandinavian “sages."

![]()

207

The partisans of the Roman theory argue that later Russian historical documents — the Chronicle of Nikon and the Stepennaja Kniga (Book of Degrees) — state that while Vladimir was in Kherson, an “ambassador from Rome came to Vladimir and brought him relics of saints.” They argue that this embassy was sent to Vladimir at his own request and had as its purpose the establishment of the Russian hierarchy in the Kievan State, after the Byzantines had refused to cooperate in this matter. But when it is examined closely, this theory is found untenable.

The Roman embassy to Vladimir at the time when he became a Christian must be regarded as an historical fact. Pope John XV, however, had very little to do with it. This embassy was sent by the Empress Theophano, widow of Otto II, who was at that time in Rome, [1] and who had special reason to be interested in Vladimir’s baptism and in his marriage. It was not difficult for Theophano to get information from Constantinople about the request sent by the Emperor Basil II to Vladimir for help against Bardas Phocas, a pretender to the imperial throne, but in order to explain this request, the Russo-Byzantine treaties of 945 and 971, by whose terms the Russian prince undertook to help the Emperor with auxiliaries whenever asked to do so must be recalled. Vladimir was pleased to oblige and, at the same time, to get rid of the Norsemen whom he had brought from Scandinavia to assist him against Jaropolk and who were growing very tiresome in their idleness. As a compensation, however, he asked for the hand in marriage of a Byzantine princess, “born in the purple,” and promised to receive baptism. The princess who was chosen to become Vladimir’s wife was Anne, daughter of the Emperor Romanos II. She was Theophano’s cousin and it seems that at one time it was Anne whom Otto I wished his son Otto II to marry. All this makes the interest which Otto’s widow took in the fate of her cousin far more comprehensible.

1. On the two other embassies to and from Russia during Vladimir’s reign see F. Dvornik, The Making of Central and Eastern Europe, pp. 179 ff.

![]()

208

The Byzantine princess did not relish the idea of marrying Vladimir and it is not to be wondered at that the Greeks tried to “forget” their commitment. The poor princess had, however, to make the best of it and to find consolation in the knowledge that for her sake her husband had dismissed his five other wives and 800 concubines — an extravagant number even for a Viking, but a figure probably improved upon by the chronicler anxious to demonstrate the transformation which baptism could bring about in a pagan soul. Theophano knew by experience what it meant to be married to a semi-barbarian and her sympathy for her cousin was extreme. Hence she sent her some saintly relics and some words of consolation. If the Pope had anything to do with the embassy, it was only to send his blessing to the bride and her husband and to endorse the message sent by the Empress Theophano. It certainly did not dawn upon him to establish a hierarchy in so distant a region.

It is true that in Russian Christianity in Vladimir’s time there were some Western usages, particularly the tithe, a Frankish invention, and certain canonical customs; but these could have penetrated from the West in a perfectly natural way. Intercourse with Germany was free and open. We learn, for example, that Vladimir’s predecessor, Jaropolk, had sent an embassy to Otto I in 973. The Annals of Lambert refer to the presence of Russian envoys at the Reichstag of Quedlinburg in that year. After Vladimir had opened another gate to the West through his occupation of the Red cities, Western influences could penetrate peacefully into Russia from Bohemia. [1]

As for the theory concerning Ochrida, there is no evidence for the assertion that the Patriarch of Ochrida had provided Kiev with a metropolitan, although Bulgarian cultural influences on Russian Christianity must be admitted. Let us remember that

1. According to the Russian Primary Chronicle and the Chronicle of Nikon, the relations between Bohemia and Vladimir’s realm were lively. Among Vladimir’s wives were two of Czech birth, and embassies sent to him by the Czech Duke “Andrich” (Oldřich) are mentioned. See for details A. V. Florovskij, Čechi i Vostočnye Slavjane (Czechs and Eastern Slavs, Prague, 1935), pp. 14-44.

![]()

209

after the death of the first Archbishop of Ochrida, John, who was a Bulgarian, the see was occupied by Greeks. [1]

The best solution of the puzzle regarding the establishment of the Kievan hierarchy will be found by taking into consideration Vladimir’s policy in the Crimea and following the lead given by the Primary Chronicle. We know that Vladimir took a lively interest in the Crimea, which was an important link between Kiev, Byzantium, the Varyago-Slav colony of Tmutorokan’ [2] on the Taman’ peninsula, the Khazars and the Near East. He surrendered Kherson, which he had occupied, to the Greeks as a token of friendship; but he was determined to keep in close touch with this eastern outpost of Byzantium. As this was also in the interests of the Emperor, it seems that a compromise was reached by establishing the Archbishop of Kherson as a kind of supervisor of the young Russian Church. An allusion to this fact is found in the statement of the Primary Chronicle that the first priests sent to Kiev were from Kherson. Moreover, at the ceremonies marking the translation of the relics of SS. Boris and Gleb, the first Russian saints, [3] it appears that the Archbishop, named John, who presided, did not reside in Kiev but came there for this special purpose. This seems to indicate that he was the autocephalous Archbishop of Kherson.

This compromise was perhaps unusual in Byzantine practice, but in the light of the circumstances, it seems perfectly natural and logical that the Byzantines should prefer to entrust the supervision of the young Russian Church to a prelate who was on good terms with Vladimir, whom he had baptized, and who was

1. Recently V. Nikolaev tried to defend the “Ochrida theory” in his book Slavjanobolgarijat faktor v christijanisacijata na Kievska Rusija (Sofia, 1949, Bulg. Academy). He brought forward no new evidence for his thesis. See the detailed review in French of his book by B. Zástěrová in Byzantinoslavica XI (1950), pp. 240-254.

2. On the theories concerning the origins of this colony see F. Dvornik, The Making of Central arid Eastern Europe, pp. 312 ff.

3. Cf. below, p. 212. The translation took place in 1020 or 1026.

![]()

210

also in direct communication with both Russia and Byzantium. This state of affairs lasted until the reign of Jaroslav the Wise, on whose initiative Kiev was raised to metropolitan status.

It was Vladimir then who laid the foundation of Kievan Christianity. The Primary Chronicle describes with great satisfaction the more spectacular manifestations of his Christian zeal — the beating of the statue of Perun by twelve muscular men and the mass baptism of the people in the Dnieper river. These spectacles were doubtless also organized to reassure the Byzantine princess that his feelings towards her were most laudable. Vladimir also had a new cathedral built in Kiev for the first bishop.

Although the methods chosen by Vladimir to implant Christianity were somewhat forceful, he encountered really stubborn opposition only in Novgorod. It may be that the introduction of the Slavonic liturgy in the new Church — thanks to the presence of Bulgarian priests, who brought Slavonic books with them — helped considerably to spread the new faith across the Russian lands. In spite of that, many pagan practices survived among the people as we can judge from complaints voiced in sermons of that time. Special embassies sent by Vladimir to the main Christian shrines made the fact that Russia had entered the Church known to the whole Christian world.

The introduction of the Slavonic liturgy also helped considerably in bringing about the amalgamation of the Varangian and Slavic elements. The Varangians were, of course, at a disadvantage when this transformation took place, and the political influence of the Varyag aristocracy decreased in proportion as the Prince derived increasingly powerful support from the Church and its clergy. All this explains how it came about that despite the important role they had played at the beginning of Russian history, the Scandinavians were unable to influence the evolution of the Russian language, and why words of Scandinavian origin in Old Russian are few. It is interesting in this respect to observe in the Kievan State an analogous development to that noticed in Bulgaria after the Christianization of the country and the introduction of Slavonic liturgy and letters. There also these factors

![]()

211

helped Boris to reduce the power of the aristocracy of Turkic origin. The Slavonic liturgy contributed also to a closer unification of the many tribes of Eastern Slavs. Thus a great new Slavonic national Church was formed which was destined to become of immense importance for the growth of national sentiment among the Eastern Slavs. From now on, the dynastic links created by the unifying action of the Varangian princes to hold the many tribes together were strengthened by new cultural and religious ties, which would prove in future even more effective than the idea of a single dynasty for the whole of Russia.

The fact that for several decades most of the Russian bishops were Greeks [1] did not interfere with this unification. On the contrary, the alien bishops were not interested in the local feuds between members of the reigning family, but only in the unity of the Church which they were governing. This unity was, of course, also in the interests of the Byzantines. Thus it happened that the Church, although under Greek supervision, rendered a great service to the Russian nation as a whole, maintaining the principle of the unity of all Russian lands.

Among Vladimir’s successors two dukes deserve special mention — Jaroslav the Wise (1036-54) and Vladimir II Monomach (1113-1125). Jaroslav was the only survivor of the fraternal strife between Vladimir’s sons lasting from 1015 to 1036 — a struggle which threatened to ruin the work of Oleg and Vladimir and which was a bad omen for the future. Two of the brothers,

1. D. Obolensky suggests that, according to an agreement concluded by the Russians with the Byzantines — probably under Jaroslav the Wise — the Metropolitan See of Kiev was to be held alternately by Greek and Russian prelates. If a native was elected, he had to be consecrated by the Patriarch of Constantinople. This suggestion is very plausible, although conclusive evidence is hardly available. Another suggestion advanced by D. Obolensky that Vladimir, when he married the Byzantine princess, was distinguished by a high Byzantine court title, perhaps even the title of Basileus, is probably correct. Both suggestions deserve detailed study.

![]()

212

Boris and Gleb, became victims of Svjatopolk and were afterwards venerated as martyred saints by the Russians.

Jaroslav’s reign was one of the most brilliant periods of Kievan Russia. He was a great church builder, and a study of Kiev’s cultural achievements will show how great a part he played in the literary and artistic development of his country. He proved also to be a wise lawgiver, and following the example of his father, who had tried to secure the frontiers against the raids of other nations, Jaroslav tried to protect the northern part of his realm, which was menaced by the Balts and the Finnish Estonians who were trying to extend their territories. The foundation of Juriev (Dorpat or Tartu) in the first half of the eleventh century was intended to put an end to the Estonian colonization of Russian lands, and Jaroslav’s expedition of about 1040 against Lithuania, in which he cooperated with the Poles, was also designed to arrest the Balts.

The only expedition which ended in disaster for him was that against the Byzantines in 1043. This was probably provoked by a disagreement which had broken out between Russian and Greek merchants in Constantinople. It was often said that this conflict induced him to undo some of his own work, i.e., the agreement reached with the Emperor and the Patriarch concerning the reorganization of the Kievan Church. According to this agreement, Kiev was to be the see of a metropolitan, who would be the head of the whole Russian Church. The metropolitan was to be consecrated and sent to Kiev by the Patriarch. He would then ordain bishops for other cities, the nominations being made in accordance with the wishes of the princes. The first Metropolitan of Kiev, Theopemptus, was sent to Russia from Constantinople about the year 1039.

It has hitherto been thought that the metropolitan would always have been Greek and that this stipulation was infringed in 1051 when Jaroslav caused a Russian, the learned Ilarion, to be elected Metropolitan of Kiev. There is, however, no evidence of such a rift between Byzantium and Kiev ensuing from this incident. Jaroslav’s move can best be explained on the basis of the

![]()

213

above-mentioned suggestion concerning a special arrangement which allowed for the See of Kiev to be occupied alternately by a Greek and a Russian prelate. It may be that there is a connection between this agreement and Jaroslav s attack on Constantinople in 1043 and the peace treaty concluded between Kiev and Byzantium which followed. But subsequently Jaroslav settled the whole dispute between Kiev and Byzantium by arranging a marriage between his son Vsevolod and a Byzantine princess.

In order to preclude feuds among his successors, Jaroslav established a new order of government. He gave to each of his five sons a principality as a kind of appanage, reserving for the eldest, Izjaslav, the cities of Kiev and Novgorod. The Prince of Kiev had to guard his pre-eminence over the others, but it appears that the old Scandinavian and Germanic influences made themselves felt again in Kiev in determining the order of succession. Jaroslav seems to have adopted the Germanic system of “tanistry,” which hitherto, however, had been followed only by the Vandals in Africa. [1] According to this system, the father is not succeeded by his son but by his younger brother, and the youngest brother is followed on the throne by the eldest of his nephews.

At first, this system was observed with some regularity. Izjaslav I (1054-1073) was followed on the throne of Kiev by his brothers Svjatoslav (1073-1076) and Vsevolod I (1078-1093). Then the succession fell to Izjaslav s son Svjatopolk II (1093-1113) and after him to Vsevolod’s son Vladimir II Monomach (1113-1125). The changes on the throne were, however, disturbed by incidents of ill omen for the future. Izjaslav failed to establish the superiority which belonged to him as the senior prince holding Kiev. He had to share his authority over the whole of Russia with his brothers Svjatoslav and Vsevolod. Then Vseslav, the Prince of Polock, great grandson of Vladimir the Great, and Rostislav of Novgorod, resenting their exclusion by Jaroslav the Wise from participation in the joint rule over Russia, started to make trouble.

1. This system was followed also in Scotland until the eleventh century, when it gave rise to the struggle between Duncan and Macbeth and was finally ended by the sons of Duncan’s son Malcolm III and St. Margaret.

![]()

214

Rostislav occupied the principality of Tmutorokan, but because this move threatened Byzantine interests in the Crimea, he was poisoned by a Byzantine agent from Kherson. Vseslav, who in 1068 was proclaimed Prince of Kiev by the Kievan population who were in revolt against Izjaslav, [1] was captured treacherously by the three brothers and expelled from Kiev by the Poles whose help Izjaslav had implored. Izjaslav, who was himself driven away from Kiev in 1073 by his brothers, asked the Pope Gregory VII for help, offering Kiev as a papal fief; but no help came [2] and he was able to return to Kiev only after Svjatoslav’s death in 1076.

Vladimir Monomach was called to the throne of Kiev by rebellious citizens who were disgruntled at Svjatopolk’s social and financial policy. He owed his popularity to his display of energy and valor during the campaign against the new invaders of southern Russia, the Cumans, called the Polovci by the Russians. Their invasions started in the sixties of the eleventh century and were devastating, though quarrels among the ruling princes facilitated their initial success. Eventually, in 1103 Svjatopolk and Vsevolod’s son Vladimir joined forces and crushed the invading hordes. The victory was crowned in 1111 by a great Russian raid deep into the steppes, and the hero of this campaign was the young Vladimir. This popularity won him the favor of the Kievans, and the rights of Svjatopolk’s brothers and Svjatoslav’s sons to succeed in Kiev were thus ignored.

Monomach started his reign with some legislative measures in favor of the lower classes and throughout his reign he showed a deep understanding of social problems. In his Poučenie — “Admonition” to his sons — he left a kind of “mirror of a good prince” for his successors. The document shows, at the same time, how

1. Vseslav survived in the Russian epic tradition as a prince-werewolf. See R. Jakobson’s and M. Szeftel’s study, “The Vseslav Epos” in Russian Epic Studies (Memoirs of the American Folklore Society, Vol. 42, edited by R. Jakobson and E. J. Simmons, Philadelphia, 1949), pp. 13-86.

2. For details see below, pp. 275, 276.

![]()

215

profoundly Christian principles had penetrated the Russian soul.

Because of his popularity, Monomach was able to leave the Kievan throne to his eldest son Mstislav I (1125-1132), whose mother was Gyda, daughter of Harold II, the last Saxon king of England. Together with his brother Jaropolk, Prince of Perejaslavl’, Mstislav I made a serious effort to secure the northern and southern borders of the Russian lands, menaced by the Finnish Estonians and the Cumans.

It seemed now as if the dynasty of Monomach would stay firmly established in Kiev. After Mstislav’s death, his brother Jaropolk II succeeded him (1132-1139). Unfortunately a quarrel that broke out among the members of Mstislav’s family for the possession of the principality of Perejaslavl’ weakened Jaropolk II’s position. As a result his brother Vjačeslav, who should have succeeded him, was driven away from Kiev by a descendant of Svjatoslav, Vsevolod II (1139-1146). A prolonged struggle between the dynasties of Monomach and Svjatoslav was the result of this intrusion, but the citizens of Kiev showed their sympathies for the dynasty of Monomach when accepting Mstislav’s son Izjaslav II (1146-1154) and rejecting Vsevolod’s brother Igor’. Izjaslav II’s succession was, however, contested by his uncle George (Jurij), Prince of Rostov-Suzdal’, the new principality in the northeast, and after a protracted struggle George, called Dolgoruki — the Longhanded — emerged victorious (1154-1157). The final result of the dynastic struggles was tragic for Kiev. George’s son Andrew, called Bogoljubskij, took possession of Kiev (1169) in order to secure his right to succession against Mstislav, son of Izjaslav II. The city was pillaged and destroyed by fire, and Andrew (1157-1174) did not think it worth while to remain there. He installed his relatives in Kiev, returned to his northeastern principality and took up residence in Vladimir, a city which had superseded Rostov and Suzdal’. The decline of Kiev was accelerated during the reign of Andrews brother Vsevolod III (1176-1212), who not only continued to reside in Vladimir but took the title of Grand-Prince of Vladimir instead of Kiev.

Contemporaneously with these dynastic struggles the Kievan

![]()

216

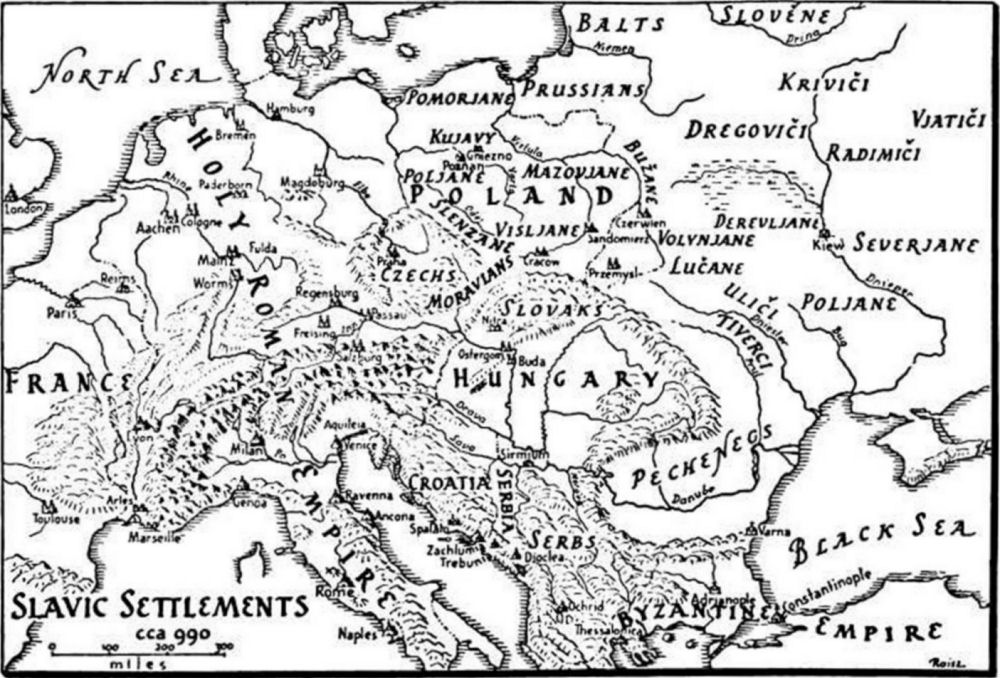

15. Slavic Settlements ca. 990

![]()

217

State was being completely transformed. The center of national wealth and political power was steadily moving from Kiev towards the northeast and the southwest. The principalities of Smolensk, Cemigov, Polock, Perejaslavl’, which were set up on the territories of the primitive tribes — the Radimiči, Drevljane, Severjane and Vjatiči — gradually increased in importance as their population grew, and Rjazan and Murom on the Oka were soon surpassed by the most northeasterly principality of Rostov-Suzdal’, between the rivers Volga, Oka and Moskva.

The territories of the southwest were also becoming more important as factors in the national development. The primitive tribes there were amalgamated under the common name of Volynjane, and the territory they occupied was called the principality of Volhynia. The westernmost Russian outpost was the fortified place of Galie (Halicz), founded by Prime Vladimir about 1140, from which the whole region derived its name — Galicia. The temporary union of Galicia with Volhynia at the beginning of the thirteenth century seemed to open new possibilities for further Russian development, although in the event they were to be frustrated.

At the same time in the north, Novgorod was developing into a great colonial power. It was sending colonists and pioneers as far as the White Sea, the basin of Pečora and the upper Volga.

What was the reason for this transformation? The dynastic struggles of the Rurik dynasty for the possession of Kiev do not explain such a massive exodus of the population towards the northeast and the southwest. Similar struggles were occurring also in the new principalities. The main reason may have been the invasions of the Cumans which were particularly devastating. The Russian Primary Chronicle registered fifty invasions between the years 1061 and 1210, besides many local raids. For this reason, and anxious to find more security, the population moved from the Kievan principality to the new lands in the northeast and the southwest where colonization had begun.

Thus ended one glorious phase in Russian history: that of the Kievan State. The new period which followed was one of

![]()

218

independent principalities held together by a common tradition and a common faith. This stage of evolution was interrupted by another Asiatic invasion, that of the Mongols, and darkness fell over the Russian lands for two long centuries. When new hope dawned in Russian hearts, all eyes turned not towards the south where stood Kiev, the cradle of Russian glory, but to the north, where on the territory of the principality of Suzdal’-Vladimir, Moscow had arisen. And it was from this new center that the idea of the unity of the Russian lands, bom in Kiev and blessed by the Church, began to be realized anew.

A survey of the main features of Kievan civilization and an examination of the inner evolution of Kievan Russia are necessary in order to analyze the reasons responsible for the rise and fall of Kiev. The problems which should be studied in this respect are many; and it is impossible to touch upon them all. Attention must therefore be concentrated upon those which seem particularly relevant.

The main source of the wealth and importance of Kiev in Europe lay in its commerce with the East. It seemed that Europe had, at last, discovered a new access to the treasures of Byzantium and the Middle East, an access which was not subject to Arab intervention. This does not mean that the Arabs did not pay any attention to what was to them an important problem; but probably the continuous struggle which they were waging with Byzantium and the Christian world in Italy and Spain prevented them from seeing the advantages of commercial intercourse with the West and from developing it more fully. In years of peace they did trade with Byzantium and some Western countries. It was, however, left to the Scandinavians to seek new ways by which commercial relations between Western Europe and the Middle East could be restored and freed from the interference of Arab pirates in the Mediterranean and Adriatic. This was achieved by the Scandinavian discovery of the Volga route to

![]()

219

the Caspian Sea and Bagdad and later by the even more important discovery of the put’ iz Varyag v Greki — the route from Scandinavia to the Greeks, following the Dnieper and the coast of the Black Sea. Because of this, Kiev became one of the most important commercial centers in Europe. From there the Scandinavian conquerors also secured the trade route leading to Central Europe, which seems to have been used earlier by the Goths. This explains the interest which Vladimir and his successors took in the so-called Red cities and Přemysl, uniting Kiev with Cracow and the Vistula on one side and with Prague, the Danube and Regensburg on the other. In fact, mention is made as early as the tenth century of Russian merchants on the upper Danube and in Prague.

These commercial relations would have become of immense and lasting importance for Russia if the Kievan princes had been able to obtain complete control of the mouths of the rivers forming the main commercial channels — the Dnieper, Dniester, Don and Volga. Unfortunately, the continual invasions of nomadic tribes coming from the interior of Asia prevented them from doing this, and their failure proved the main handicap to Kievan trade. The Khazars, however, understood the importance of commercial intercourse. After some time, even the Pechenegs were brought to see reason, and they concluded special trading arrangements with the Russians; but the Cumans and, after them, the Mongols extinguished all hopes that normal commercial intercourse would be continued.

This was all the more serious because, in the meantime, the West had on its own initiative opened a new Mediterranean route towards the Middle East by establishing a number of Christian states in Syria and Palestine after the First Crusade (1096-1099). In spite of this, there was still the possibility of trade with Byzantium in the south and with Scandinavia, the Baltic countries, Flanders and England in the north. The conquest of Constantinople by the Latins in 1204, however, put a definite end to a prosperous relationship with what was left of Byzantium. In the north, only Novgorod was left in a position to trade with northern

![]()

220

Europe, Germany and the interior of Russia — a circumstance which saved this city from the sad fate which overcame the rest of Russia.

Russian exports were largely limited to raw materials — furs, wax, honey, flax, hemp, tow, burlap, hops, tallow, fats and hides, not to mention, especially in the tenth century, slaves. There was also a certain amount of transit trade, the Russian merchants re-exporting to Central and Northern Europe goods which they had obtained from Byzantium such as precious stones, spices, rugs, silks and satins and weapons of Damascus steel.

At first, foreign money was used in commercial transactions. This is illustrated by numerous finds of Arab, Byzantine and Scandinavian coins in many different places, which are particularly numerous for the ninth and tenth centuries. Apart from these, especially in the markets of the interior, certain kinds of furs were used as currency. Later, there appeared a form of metal currency — grivna — the value of which, however, was not very stable. In the reign of Vladimir, silver and gold coins were minted bearing the Duke’s emblem. This was the beginning of the Russian monetary system, although furs continued to be favored in barter.

It was natural that commercial relations should exercise an important influence on the economic, social and political evolution of Russia. There is, in fact, a great difference in this respect between Russia and that part of Central Europe which was transformed by the Germanic migrations. In the Carolingian period and afterwards, the national economy of Central Europe was centered in the manors of the aristocratic landowners. Cities began to spring up only in a much later period, the twelfth century, when artisans and merchants had found their place in the national economy. In Kievan Russia, the situation was different. Trade could develop only in cities, and the market place was the center where townsfolk and country people met. It soon

![]()

221

became associated with political life and administration. All public announcements were made in the public market, and judges would open their enquiries into, say, a case of theft only after the plaintiff had proclaimed the details of the incident in the market place.

The most important citizens were, naturally, the merchants, who frequently exerted a considerable influence on the economic and political life of the nation. They formed companies and guilds for their own purposes. Their example was followed by artisans who united in cooperative associations. The importance of the city in national life is illustrated by the existence of the veče, the city assembly, an institution which was a characteristic of Kievan Russia. It developed from the old council of family chiefs common to all Indo-European nations. As, thanks to the merchants, national life became centralized in the cities, these assemblies of family heads grew in importance. In minor cities the assemblies limited their activities to dealing with purely local matters, but the veče in the capital cities became a weighty political institution. It was presided over by the mayor, who called its members together whenever the necessity arose. The veče would meet near the ducal palace, or in the square before the cathedral church, or in the market place. Sometimes it had a voice in deciding the succession to the throne. Sometimes it claimed the right to voice dissatisfaction with the ruling prince, even going so far as to call for his abdication. Usually, it supported the prince and his council in matters of legislation and administration. The dukes of Kiev generally succeeded in keeping the assembly under control; but in Novgorod the veče achieved the zenith of its power.

Thus it came about that the city inhabitants became a significant element in the state, although they were far fewer than the free peasantry, called smerdi. [1] These latter continued to live in the zadruga (great families) and regarded the soil which they

1. On the low social position of the smerdi see the study by Y. Blum “The Smerdi in Kievan Russia," The Amer. Slavic and East Europ. Review XII (1953), pp. 122-130.

![]()

222

tilled as being the common property of all members of the great families. On this basis the verv’, a local community similar to the Anglo-Saxon guild, developed and was superseded later by the peasant commune (obščina, mir). In addition to the free peasantry there were also peasants who worked on the estates of the boyars, and slaves.

The upper classes were formed from the natives — Slavs, muži, leaders of clans and tribes — or from aliens — Scandinavians. From the second half of the eleventh century, however, the distinction between them began to disappear, and both merged into one class of the privileged boyars. The melting pot for this transformation was the družina — the retinues of the princes, composed at first of Scandinavian warriors and servants. From the old members the duke chose his posadniks, or representatives in the provincial administration. From the members of the retinue the duke also chose the tysjatsky, the city governor, who was also the commander of the city militia. At the beginning, he must have been elected by the people and was considered to represent the people before the ruler. This practice was continued in Novgorod. The prince also chose the members of his private council, the duma, from among the older members of his družina. Besides them, the native boyars, bishops and representatives of the merchants were also regarded as the duke’s councillors.

There is a problem which is still debated by specialists in early Russian history: the question of feudalism in the Kievan period. There is no room to discuss this in detail, but it is pertinent to recall what happened in this respect in Byzantium. Feudalism was not a Byzantine institution, and the emperors struggled hard to prevent the disappearance of the free peasantry and the concentration of landed property in the hands of a powerful aristocracy. But they were unable to arrest the course of evolution. The impoverishment of the free peasantry, due to high taxation and foreign invasions, played into the hands of the landed aristocracy,

![]()

223

who promised protection and help in return for the surrender of the free use of the peasants’ land. A similar evolution had occurred in Bulgaria, and the same symptoms can also be observed in Kievan Russia during the period of its decline and before the onslaught of the Mongols. The deti boyarshie (sons of the boyars) and the zakladničestvo, which we find in the later Kievan period, were a Russian version of the Greek and Bulgarian paroikoi — free peasants who sought the help and protection of the rich and mighty. [1]

It is thus evident, even from this short review of the economic, social and political conditions of Kievan Russia, that there was a basic difference in this respect between the Kievan State and the rest of Europe. The main reason for this difference was economic — the flourishing trade that went on between the North and the East. This circumstance enhanced the importance of cities in the national life and helped to replace the old tribal organization by a regional grouping of the population around cities as centers of administration. Nowhere else in Europe do we find the coexistence of city states and monarchic institutions such as developed in Kievan Russia. This was the basis of Kiev’s strength — and also of its weakness. This special social structure delayed the evolution of feudalism, which dominated the scene in contemporary Europe; but the crisis in trade, brought about by the invasions and by the activities of the Crusaders, combined with the lack of monarchic strength, brought about the collapse of Kiev.

The high level of Russian civilization in the Kievan period and its character are indicated by what we have learned about the economic evolution of the country and its relations with the rest of Europe. The vast incomes which the princes gathered from tribute paid by their subjects and from their personal participation

1. On the further evolution of Russian feudalism see G. Vernadsky’s study “Feudalism in Russia," Speculum XIV (1939), pp. 300-323.

![]()

224

in trade enabled them to indulge a remarkable activity in the field of architecture. The artistic inspiration naturally came from Byzantium but also from the West and from the Near East; but Russian artists soon learned the secrets which their masters revealed to them, and they improved upon them.

Another important feature of Kievan civilization is that it was not closed to Western influences. These can be traced in its literary achievements, its juridical evolution and its religious life, and the stepping stone for these influences was eleventh-century Bohemia.

First of all, Byzantium’s legacy to Russia in art was particularly generous, and the first dukes of Kiev spent lavishly to take advantage of it. In 989, Vladimir built a church of the Assumption in Kiev which was destroyed by the Mongols in 1240. The church of the Holy Wisdom (St. Sophia), begun in Kiev by Jaroslav the Wise and built during the years 1037-1100, is a jewel of Byzantine art, erected and embellished by Greek artists; and to obtain a correct impression of Greek art and architecture of the eleventh century, it is necessary to study the church in Kiev. Later the church of the Holy Wisdom in Novgorod (1045-1054) — as well as the Nereditsa church (1198)—followed the pattern of the Holy Wisdom of Kiev, and its bold lines converging on a crown of thirteen cupolas must have appealed strongly to the tastes of the Russians since they made it one of the characteristic features of all their subsequent ecclesiastical architecture. Unfortunately little remains of Byzantine architecture and art of the same period on the soil of the Empire itself.

Kiev had its second school of arts, founded by Byzantine masters, who introduced the new architectural style of which the church of Our Lady’s Assumption in the Monastery of the Caves in Kiev was the first typical example. It was constructed in 1089, but was almost completely destroyed in the second World War. Two other churches, those of the monasteries of St. Cyril (1140) and of St. Michael with the Golden Cupola (1108), followed the pattern of the church of the Assumption, and this style also found its way north of Kiev to Černigov.

![]()

225

Besides architecture, the decorative arts also received inspiration from Byzantium. The mosaics and frescoes of St. Sophia of Kiev were discovered in 1843 and have since attracted much attention from historians of art. They are of singular beauty, some of them exceptionally striking for their vigorous design and expressive reality. Native artists soon began to imitate their Byzantine masters. Amongst them, Olympius, a monk of the Monastery of the Caves, was especially gifted, and the mosaics of St. Michael with the Golden Cupola are attributed to him. He lacks the dexterity and refinement of technique of his Creek masters; but shows remarkable originality in the conception of his figures which, less rigid than those of St. Sophia, are much more lifelike and varied. His work is one of the finest examples of medieval Russian religious art.

From the twelfth century there are also the frescoes of Novgorod and Vladimir, which are in part the production of native artists.

The practice of painting icons also owes its origin to Byzantine inspiration. In this respect, the famous icon, Our Lady of Vladimir, deserves special mention. Painted in the eleventh or very early twelfth century and of Byzantine origin, it has inspired millions of Russians and was from the first admired and imitated because of its touching and unaffected beauty. The painting of icons developed into a special Russian form of religious art, in which native originality found a remarkable expression.

In the sphere of literature, Kievan Russia was most fortunate in that, from the very beginning of its Christian life, it was in possession of all the treasures of the Old Slavonic literature bequeathed to Moravia by SS. Cyril and Methodius. These were salvaged by their disciples, when the Moravian Empire collapsed, and brought by them to Bulgaria. The Bulgarians considerably enriched this heritage before they transmitted it to the Russians. Thus the catastrophe which befell Bulgaria in the

![]()

226

tenth century, when it became a Byzantine province, proved to be of inestimable benefit to Russia, for many Bulgarian refugees fled there carrying with them copies of Old Slavonic literary works.

Another agency, so far overlooked, which was instrumental in introducing Slavonic letters into Kievan Russia was Bohemia. Historians were not clear about the extent of the Přemyslide State and the spread of the Slavonic liturgy in the Czech lands; but it is now known that Slavonic literature flourished in Bohemia throughout the tenth and eleventh centuries. As to the extent of the Přemyslide State, it is also known that, after the loss of Cracow and what remained of White Croatia, the Přemyslides held Moravia and Slovakia until the beginning of the eleventh century, when these two countries were occupied by Boleslas the Great of Poland. Then, in the tenth century, Poland, Kievan Russia and Bohemia met in the Carpathian Mountains. This made access from Bohemia into Kievan Russia very easy and explains, for example, how the manuscript of Vita Methodii found its way into Russia. Indeed, the preservation of this literary treasure is due to that happy circumstance.