VIII. The Albanians

1. The Albanian Character

THERE is no race in European Turkey which enjoys collectively a reputation quite so unenviable as that of the Albanians. They are the bêtes noires of the Embassies, the scapegoats of the Porte. If anywhere the Turks are engaged in punitive operations, it is a mere matter of routine that some or all of the Ambassadors should protest against the employment of Albanian troops. If anywhere excesses have been committed which even the Sultan cannot deny, the inevitable excuse is that the Albanians "got out of hand." One suspects that the first exercise of a diplomatic tyro is to draft these warnings with the dates blank for future use, and the first essay of a probationer in the Grand Vizier's office to turn the hackneyed exculpatory phrases with the requisite note of surprised and horrified humanity. For a century past this ill name was the only herald which brought the Albanians to the knowledge of the West. We heard of them when their massacres threatened to exterminate the Greek race in the Morea. We heard of them when France and England intrigued for the friendship of Ali Pasha, each fascinated by his reputation for superhuman cruelty and cunning. We heard of them again as the race whose exactions and oppressions in "Old Servia" vie with the performances of the Kurds in Armenia. And the Blue-Book (1904) which recorded the atrocities in Macedonia and Adrianople fits the Albanian name once more into the familiar context of execration and complaint.

![]()

![]()

222

Of all their vague political aspirations and obscure strivings nothing seems to have been known save the one damning fact that they had risen to protest against the reforms. It has been their fate to hide their virtues under an alias, and to commit only their crimes and errors in their own name. Whether as Christians or as Moslems their lot has been to win laurels for other races. How much of the great legend of the Greek War of Independence would remain if the share which the Christian Albanians had in it were subtracted? When one thinks of that various struggle, sometimes savage, sometimes heroic, two chapters emerge which have specially seized the imagination of Europe — the wars of Suli against Ali Pasha, and the exploits of the seamen of Hydra against the Turkish navy. Both the Suliotes and Hydriotes were Albanians in blood, language, and customs. They were "Greeks" only in the sense that the Vlachs are "Greeks" — they belonged to the Orthodox Church, and if any of them possessed any culture at all, it was Greek culture. The Suliotes were a predatory tribe, rather better organised and more homogeneous than most Albanian septs, and their manners had not been softened by their nominal Christianity. The Hydriotes were simply pirates. The heroism and tenacity which both displayed as their normal opposition to the Turks deepened under Greek influence into a struggle for political liberty, have cast a lustre and a glory upon the whole war which ought by every law of historical justice to modify the judgment which civilisation has passed upon the Albanians. As the Christian Albanians have worked for the greater glory of the Hellenic idea, so the Mohamedan Albanians have contributed to such sympathy as the Turks can still command in the West. The word "Turk" in our language has a racial rather than a religious connotation. But in the languages of the East it is simply a synonym for Mohamedan. The Greeks, for example, even speak of the Moslems of Crete as "Turks," although they are Hellenes by race and language who can rarely speak more than a very few words of Turkish. And so it is with the Albanians. All over Turkey they are to be found in positions which bring them into

![]()

223

contact with Europeans. They are sometimes governors, often military officers, while the typical trade of the lower class is that of cavass, i.e., armed servant, half courier, half bodyguard, in the pay of some European or wealthy native. The superb men in picturesque garb, decorated with a bewildering variety of weapons, who lounge at the doors of consulates and banks, who carry money or messages, or hire themselves out to escort travellers, are invariably Albanians. But because they are nominal Moslems the hasty traveller classes them as Turks, and goes home to spread abroad the fame of their fidelity, their self-respect, their courage, and their sense of honour — qualities which somehow transform themselves into so many arguments for the continuance of Ottoman rule. I once travelled over one of the Macedonian railway lines with a young Englishman of wealth and position who was making a tour of the Near East as a preparation for a parliamentary career. He had no very settled convictions, but at every turn of the conversation he broke into eulogies of the individual "Turk." At last I asked him on what he based his judgment. "Well," was the answer, "look at my servant." The man turned out to be a characteristic Albanian — tall, handsome, and doubtless as honest and brave as his eyes were frank and fearless, while his whole bearing conveyed that suggestion of mingled courtesy and independence which makes the peculiar charm of his race. It seemed a hard fate that his fine qualities should all the while be winning a partisan for an Asiatic despotism which every good Albanian despises and detests.

For in sharp contrast to the reputation which the Albanians have won for themselves collectively, is the regard in which they are held as individuals not only by Europeans but by other native races in the Balkans. As tribesmen they may be inveterate and reckless brigands, whose annual incursions into the richer regions of the Macedonian borderland are the natural consequence of their contempt for any tool save the rifle. As soldiers they are the terror alike of their Turkish officers, whom they despise, and of the Christian populations, whom they terrorise.

![]()

224

But let them once abandon the profession of arms and immediately their simple feudal virtues seem to win them patrons and even admirers. They are valued all over Macedonia as masons or navvies — these men who would scorn to turn a sod in their own country. They are cunning craftsmen, and in silver work display not only dexterity but taste. In positions of trust their honesty is as proverbial as their courage. The most timid Levantine merchant will confide to them his money and his life if only they have given their word to be true. The unsophisticated Turkish peasant — a very different man from the nondescript Moslem Levantine of the towns — is usually both honest and truthful, but one feels that his virtues spring in no small degree from his notorious lack of enterprise and imagination. The key to the Albanian temperament is, on the other hand, a sensitive and somewhat aggressive pride. At its lowest it is a picturesque and amiable vanity, at its best it is a fine self-respect. He has the same quickness of wit, the same tense nerves as the Greek, and the same spirit of enterprise. But his pride saves him alike from cowardice and from meanness. He will rob openly and with violence, but he will not steal. He will torture an enemy, but he will not touch a woman. If he swaggers and boasts and puts a certain truculence into his very dress, he has much too high an opinion of himself to lie meanly in self-defence. He has the traditions of a race which has fought for the Turk as his mercenaries, but has never accepted his domestic rule without protest. An Albanian's sense of honour is not entirely external. He will murder you without remorse if he conceives that you have insulted him — as Turkish officers and Russian consuls have learned to their cost — and if the murderer, a lonely outlaw, should find his way even to a strange and possibly hostile tribe, it will fight to the last man rather than surrender him to the authorities. [1] But he

1. It is pretty generally understood in Turkey that it is death to strike an Albanian. But occasionally a Turkish officer forgets himself. A case occurred at Vodena in the summer of 1904, and the whole garrison went into mutiny until it had found and slaughtered the erring lieutenant.

![]()

225

is equally punctilious about his own pledged word. To keep it he will face any risk himself, and to help him to keep it, his tribe will think no sacrifice extravagant. It is extremely mediaeval, no doubt, this Albanian sense of honour, but if it has the crudity and bloody-mindedness, it has also the chivalry and something of the inward dignity of the knightly spirit.

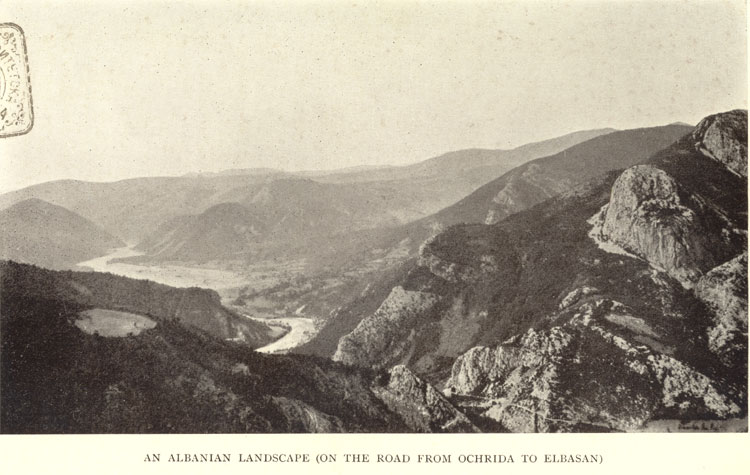

An incident which made a profound impression on me will serve to show better than any testimony in general terms what is the usual attitude towards the Albanians of those who know them best. It was necessary in the course of the relief work undertaken by the British Fund in Macedonia last winter to send large sums of money in gold from Monastir to Ochrida, Resna, and other places where we had centres. The usual method was to send our Albanian cavass, a lad named Hassan, on horseback over the mountains with his rifle on his shoulder and the money in his belt. No one ever seemed to question his trustworthiness. He carried first small sums and then large, and there was never a penny missing. He had arrived one day in Ochrida with a matter of £400, and he stood while I counted it with his air of ingenuousness and quiet self-confidence which suggested an English public schoolboy rather than a Balkan peasant. It was a face that no one could fail to trust, kindly and gentle yet spirited, with its blue eyes and the blonde hair that might have been English or Norse. The money was right, as usual, and something which we had to discuss caused me to ask Hassan if he knew the whereabouts of a certain house in Ochrida — rambling city of dark lanes and deserted byways, half ruins, half streets. He smiled at the question. He knew every inch of the town. There was something humorous in the twinkle of his eye which made me ask how that could be. He came from a distant part, and had lived for a year or two in Monastir. And then, frank, unblushing, and delightfully natural, he gave the answer, "I was with Shahin." I found myself instinctively, stupidly fearing for the money-bags on the table, for Shahin (the falcon) was the most notable of all the brigands in the countryside, a

![]()

226

sort of Robin Hood, who robbed with art and murdered with irony. He was in some sort the uncrowned tyrant of these regions. Young gallants who could not win a consent from an unsympathetic parent to a match with the lady of their heart went to Shahin to force it. He once held up to ransom a Protestant missionary whose brother was in the very house in which we were sitting. Every village had its own tale of Shahin's justice or Shahin's cruelty. And Hassan had been a member of his band, learning the topography of Ochrida in midnight raids and ambuscades at dawn.

I told the story to a friend. "Why should you distrust the lad ?" said he. "Brigandage is a profession like another. While he was a brigand he was true to the band; while he is in your service he will be true to you." And indeed Hassan himself had made his avowal much as an English youth might have said, "I served in the Imperial Yeomanry" or "I was with Baden-Powell." But most significant of all was the laconic question with which a Bulgarian Bishop replied to my inquiry. "Would you trust him ?" I asked. "He is an Albanian. Is he not ?" was the answer. For centuries the Slavs and the Albanians have been in deadly, unremitting feud. And here was the comment of one enemy on the character of the other.

Hassan was a peasant and a Mohamedan. But we had even better opportunities of gauging the qualities of other Albanians, who belonged to every Christian sect and to the most various levels of culture. There was no intention or consciousness behind it, but none the less when I count over the natives who assisted us in one capacity or another in our seven relief dépôts, I find that there were fifteen Albanians and only six of other races, and of these six only two were in responsible positions, and one of the two proved to be unsuitable. Of the fifteen Albanians, only one ever earned the lightest reprimand, and though they handled many thousands of pounds among them, I would guarantee the scrupulous honesty of every man of them. I remember going on my arrival to one of the Protestant missionaries to ask him to recommend me

![]()

227

some honest assistants for the purchase and distribution of food, blankets, clothing, &c. He was quite sure that he could do so — Protestantism in his eyes was the one guarantee of honesty. When his list was complete I noticed that every name in it was Albanian, which was odd, since the Protestant mission is supposed to be a mission to Bulgarians. The Catholic priest was equally sure that honesty is incompatible with Eastern Christianity, and he too was ready to produce the one honest native in Monastir, of course, a Catholic. When it turned out that this man also was an Albanian, I felt no small relief. Here at length is a race which neither religion nor education can corrupt. In the end our Albanian staff included Moslems, "Greeks," Protestants, and Catholics. I think one of the bravest men I have ever known was one of the Protestants. He had a superb physique, but he had been born in a town and had never carried arms. At the time when the Turkish authorities in Castoria were molesting the Bulgarian peasants who came into our hospital, beating some of them, detaining others, and carrying off a few against their will to the Turkish ambulance, I sent this man to take his stand at the gate of the town, and inform me at once if any violence was offered to our protégés. He had not long to wait, but instead of losing time while he ran for me, he dealt with the situation himself. He marched boldly, unarmed "Giaour" though he was, into the midst of the Turkish soldiers and gendarmes, rescued the Bulgarian peasants by main force and escorted them triumphantly to our hospital. The possession of a rifle will often make a man of a Bulgarian insurgent, but only an Albanian could have showed such courage as this, unarmed, against a crowd of Turks with weapons. But there are in the Albanian nature even rarer capacities than this. Honesty and courage in different degrees are the possession of all true mountaineers. The Albanian Sisters of the Order of St. Vincent de Paul, who worked at Monastir under the direction of a French superior, and in our Castoria hospital under an English lady, Sister Augustine, gave proof of a rare devotion. Born in a country where no woman dreams of any sphere outside

![]()

228

the home that is almost a harem, they had imbibed all the spirit of

practical charity and disciplined kindliness which distinguishes their

Order. They shrank neither from exposure nor infection nor fatigue, and

no European lady with centuries of civilisation behind her could have been

more gentle or more sympathetic. They all came from the wild regions of

Northern Albania, and I suppose the men of the families they had renounced

are still savages in all essentials. And yet it was always with an effort

that one realised that these women, who spoke a cultivated French and thought

in terms of Western Christianity, were the sisters and daughters of Gheg

clansmen. Their religion was to them a daily comfort and an exalted stimulus,

and one felt in their presence that if the Catholic Church can extend its

work of education, even the most benighted region of Albania may have a

future.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]