SPEROS VRYONIS, Jr.

RELIGIOUS CHANGES AND PATTERNS IN THE BALKANS, 14TH-16TH CENTURIES

When the Byzantine and Turkish worlds came into contact in the 14th century, and until the former was subdued and the latter crystallized in the 16th century, there were two basic formal religio-political systems in the Balkans: The Orthodox Basileia and the Muslim Sultanate. Each political form was intimately affiliated with an intellectually refined theological dogma propagated and maintained by a sacerdotal class which enjoyed the political and economic support of the rulers and the bureaucracy. Thus one might assume that a discussion of religious changes and patterns in the Balkans during these two centuries would, essentially, entail an examination of the Orthodox religious structure and dogma in relation to those of triumphant Sunni Islam.

Inasmuch as one is dealing with a period in which religious thought and concern for salvation were still the foremost preoccupations of most people, it would be a serious failure were one to consider the present subject only in terms of the formal culture of the ruling classes. The latter usually formed less than 10% of the total population and most frequently the divergences between folk and formal cultures were extensive. Consequently the evolution and change which took place in the Balkans during the late medieval period occurred not only on the formal level of culture and society but also on the folk level. Though the developments on the formal level invariably exercise an important influence on the folk level, especially when the state is sufficiently centralized, long lived, and possessed of a vital urban network, the partial isolation and autarky of life on the folk level produce an evolution, particularly in religious life, which can preserve extremely archaic features even when these features are in direct conflict with the dominant strains of formal religion. Thus in examining the relations of Islam and Christianity in the Balkans during this crucial period of change we shall

![]()

152

be talking not so much about the relations of Orthodox Christianity and Sunni Islam on the formal level of culture, but rather about relations of Islam and Christianity (most broadly conceived) on the folk level.

In order to conceptualize the possible permutations and combinations of emerging religious changes and patterns one must, momentarily, dispense with the conceptualization of the Balkans as divided between the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Sheyh’ul Islam of Istanbul. For neither the one nor the other was ever completely successful in imposing an absolute religious harmony and obedience upon his respective flock. In each following were to be found heretical, heterodox, and even pagan elements. Sometimes the heretical element constituted a state within a state, whereas heterodox and pagan elements were so firmly entrenched in the folk and formal culture that they were either accepted or else overlooked. There was a tension (among the various elements), therefore, within each of these two major religions, as well as a tension between the two religions themselves. The scheme of such religious variety becomes more complex if we include the categories of Catholics, Armenians, and Jews, who constituted the religious minorities in the area under consideration.

This paper will present a tripartite discussion of the subject : First it will list and describe the various types of religiosity in the Balkans at the beginning of this transitional period. Then it will examine the basic religious transition from Christianity to Islam from the 14th to the 16th centuries, its course, causes, and extent. Finally it will discuss examples and patterns of this change from Christianity to Islam and in so doing will try to illustrate the variety of combinations and of the resultant forms of Islam. The paper will be primarily concerned with the Orthodox core area of the Balkans, and will not discuss Croatia, Dalmatia, Slovenia, or Rumania.

I. VARIOUS TYPES OF RELIGIOSITY IN THE BALKANS AT THE BEGINNING OF THIS PERIOD

Christianity

There is no evidence that large blocks of overt pagans existed in the Balkans at the time of the Turkish invasions in the 14th-15th centuries. Orthodox and Latin Christianity had spread throughout the area in two major waves: in the 4th-6th centuries and then again in the period

![]()

153

beginning with the 9th century. Thus the Turks found an area which was, at least formally, almost completely Christian, and of which the major portion was Orthodox. This Orthodoxy was characterized by a uniform dogma and set of canons which had emerged from the seven ecumenical councils and which had received further amplification at the hands of commentators. The formal religious apparatus was closely intertwined with political life and its history is a reflection of the political history of the area. As Byzantium declined and the Balkan states emerged, the administrative jurisdiction of the patriarchate receded and the Bulgars and Serbs acquired their own patriarchates. The crystallization of the Serbian, Bulgarian states and the retrenchment of the Byzantine Empire in this period produced three political entities which came to constitute the precursors of their modern counterparts. Their patriarchates were thus national-political churches. In spite of the national-political splintering of the body of the Orthodox in the Balkans, formal dogma and cult were identical.

Nevertheless the struggle between heresy and Orthodoxy had been a lively one in many parts of the Balkans, particularly since the 8th century when the emperors had settled colonies of Anatolian Paulicians in the southeast Balkans. The appearance of the affiliated sect of the Bogomils in the 10th century was to exercise governments of the Balkans for a long period of time. Byzantine, Bulgar, and Serbian rulers fought the sectaries tooth and nail and, it would seem, succeeded in reducing them extensively. In the case of Bosnia the appearance of a heretical sect from the mid-12th century and its subsequent history have occasioned a lively dispute in scholarly circles. This has ranged from the question as to whether the Bosnian Church was heretic, Orthodox, or Catholic, to the religious identity of the famous grave stones of the region. Though I do not enter into these thorny questions in any detail as they are the domain of a very few specialists, it would seem that the Bogomils had their most persistant effect in the regions of Bosnia, though the vague evidence as to their relative numbers in the 15th century does not conclusively prove that they were a majority of the population. There were other smaller and more obscure heresies such as those mentioned by the 1 lth-century author Psellus, but they need not detain us here. [1]

1. On the relation of Bogomilism and Islamization, the two opposed points of view are represented by M. Okić, "Les Kristians (Bogomiles Parfaits) de Bosnie d'après les documents turcs inédits", Südost-Forschungen XIX (1960), 108-133, and B. Djurdjev, "Bosna", EI2. Okić has stated that the majority of Christians in Bosnia prior to the Turkish conquest were Bogomils and implies that mass convesion of the Bogomils took place between the conquest of 1463 and the census of 1468-1469. Djurdjev is convincing, however, in his demonstration of the opposite view, that 26 years after the conquest (in 1489) the Bosnian Christians still formed a large majority of the population. M. Wenzel, "Bosnian and Herzegovinian Tombstones and who made them and why", Südost-Forschungen XXI (1961), 102-143, has shown good cause to doubt the Bogomil nature of the Bosnian tombstones.

![]()

154

Within this Orthodox enclave there were small groups of Latin Christians, especially in the Ionian and Aegean isles, in Galata and Constantinople, coastal Albania, and in the various commercial emporia of the Balkans. They were, of course, predominant in Dalmatia, Croatia, Slovenia, and the Magyar presence gave them strength in Bosnia. Jewish merchants and craftsmen (including the Keraites) had been present for centuries, but their numbers would become substantial only after the Ottoman conquests and the flight of the Jews from Spain.

Thus Byzantium, Serbia, and Bulgaria would appear as states which were predominantly Orthodox at the time that the first Ottoman invaders crossed from Anatolia to the Balkans. Though this assumption is absolutely true in terms of the formal institutional life of the Orthodox, it is invalid for the folk culture of the inhabitants of these three medieval states. The religious life of the Orthodox masses resided on a foundation which was heavily influenced by their pagan roots. It is a pity that many Byzantinists have so little interested themselves in the life of the peasantry, preferring to focus almost exclusively on the imperial and patriarchal courts. Consequently in discussing the religious history of Byzantium they have seen deviations almost exclusively in terms of heresy and so have emphasized heresy as the primary opponent of religious Orthodoxy. In actuality, paganism exercised a far more subversive effect on religious Orthodoxy, and one could even argue that, in the case of Balkan Orthodoxy, Christianity won a Pyrrhic victory at best. The price of this victory was the acceptance or toleration of entire categories of pagan beliefs, superstitions and practices. Consequently the popular religion of the Balkan peoples, even in modern times, displays many pronounced archaic features which predate the appearance of both Islam and Christianity in the Balkans. This is perhaps not so surprising if we consider the late appearance of Christianity among the Slavs (9th century) and that the Greeks of the southern half of the Péloponnèse received Christian baptism only in the reign of Basil I (867-886). Christianity triumphed, but only after a long struggle and one in which it had to compromise repeatedly. Literati and religious leaders were conscious of the tenacious survival of paganism throughout the course of Byzantine history and have left a considerable testimonial to this fact. A 10th

![]()

155

century scholiast (possibly Arethas) on the Antigone of Sophocles comments on line 264 of the drama, which deals with μύδρος (the red hot iron which one held when swearing an oath in antiquity) as follows: "Mudros: red-hot iron. The Rhomaioi still practice this today, erring in the Hellenic fashion in most everything else." [2] A later author, John Canabutzes (15th c.) in his commentary on Dionysius of Halicarnassus, relates that, "The Christians continue to reek and stink of Hellenic (pagan) obscenity." [3] This 'pagan obscenity', to which Canabutzes and Arethas referred, continued to people the world of nature with spirits of all kinds. The lamia, or weather spirits, it was believed, presided over storms and clouds and when they fought, the clashing of the steel caused hail to fall from the heavens. In a Slavo-Christianized version the prophet Elijah chased them across the heavens in his fiery chariot. [4] The forests, mountains, and waters were the domains of female spirits or nymphs, known to the Greeks as dryads, oreads, and nereids. It was this pagan belief, so widespread in the 15th century, which occasioned Canabutzes to remark that, "The Christians continue to reek and stink of Hellenic obscenity." The house snake as the protective spirit of the hearth is common to all the Balkan peoples and is obviously of very early origin, having nothing to do with Christianity. Zeus Ktesios, as protector of the hearth, usually took the form of a serpent, perhaps an indication that this element was absorbed by the ancient Greeks from their predecessors in the Balkans. [5] The cult of the tree, widespread in most areas of the inhabited world, survives today in the Serbian zapis or holy tree. Annually, at the time of the ripening of the crops, the priest led a procession (litija) to the tree, a lamb was sacrificed by the side of the tree, and then the blood was spilled upon it. [6]

The conceptions and practices which, among the Balkan Christians, were associated with the life cycle of the human being were no less rooted

2. The scholium is edited by P. Papageorgios, Scholia vetera (Leipzig, 1888), p. 148. B. Lavagnini, "Sopravvivenze in Tracia di riti pagani e uno scolio bizantino all'Antigone", La Parola del Passato VII (1952), 145-148. I wish to thank my colleague, Prof. Milton Anastos, for first having called my attention to this interesting passage. Other authors and sources on the survival of such pagan elements include the proceedings of the Council in Trullo, Constantine Porphyrogennitus, Eustathius of Thessaloniki, Balsamon, and Joseph Bryennius.

3. M. Lehnerdt, Iannis Canabutzae magistri ad phncipem Aeni et Samothraces in Dionysium Halicarnasensem commentarins (Leipzig, 1890), p. 42.

4. E. Schneeweis, Serbokroatische Volkskunde. Erste Teil: Volksglaube und Volksbrauch (Berlin, 1961), pp. 12-13. M. S. Filipović, "Volksglauben auf dem Balkan, einige Betrachtungen", Südost-Forschungen XIX (1960), 246.

5. M. Nilsson, Greek Popular Religion (New York, 1940), pp. 67-71, 71-72.

6. Schneeweis, op. cit., p. 15.

![]()

156

in pre-Christian traditions. In the eastern and southern Balkans the belief that the three moirai presided over the fate of the newborn child is a clear case of pagan survival. [7] The institution of marriage, both among Christian Greeks and Slavs, long remained a civil affair, and even after the church and state succeeded in making of it an ecclesiastical matter, many of the elements formerly attendant upon the institution were accepted, the most obvious case being the use of marriage crowns. [8] The Balkan Christians continued to observe the older customs accompanying death and burial: the employment of professional female mourners; the placing of money in the grave (Charon's obol); the preparation of boiled wheat with raisins, sugar, almonds, and pomegranate (kollyva-panspermia); the funeral meal; the official observance of mourning for a one year period. These are only some of the many pre-Christian observances. [9] The Christian concept of hell and the after-life was affected by the Greek Charon-Hades and more spectacularly by the Slavic fear of the returning dead, the vukodlak. [10]

Throughout the countless political and religious changes in the long history of the Balkans, the peasant's way of life changed remarkably little. His abiding concerns were the fertility of the soil and propitious climatic conditions. His religious and superstitious practices were all geared to promote this fertility. In this respect one of the most interesting pagan survivals among certain of the Bulgar and Greek peasants of Thrace are the so-called Anastenarides and the Kalogeros-Kukeri mimes. The former is an eight day celebration which the thiasos of the Anastenarides commences on the feast day of St. Helen and Constantine (in May) and is accompanied by animal sacrifice, dance-induced ecstasy, fire walking (pyrobasia) and oreibasia (nocturnal wandering in the mountains). [11] The Kalogeros or Kukeri mimes take place on Cheese Monday and are very obviously intended to assure the fertility of the fields. The

7. Filipović, loc. cit., 246. Nilsson, op. cit., pp. 14-15, gives an example from 19th-century Athens.

8. Schneeweis, op. cit., pp. 57-83.

9. The important study of D. Loucatos, "Λαογραικαὶ περὶ τελευτῆς ἐνδείξεις παρὰ Ἰωάννῃ τῷ Χρυσοστόμῳ", Ἐπετηρἰς τοῦ λαογροϕικοῠ ἀρχείου, (1940), 30-117, demonstrates that the church fathers fought a losing battle against pagan funereal practices. Schneeweis, op. cit., pp. 106-107.

10. Schneeweis, op. cit., pp. 8-11, 33. Nilsson, op. cit., pp. 115-116, 119-120.

11. G. Megas, Ἑλλημικαὶἑορταὶ καὶ ἔθιμα τῆς λαϊκῆς λατρείας (Athens, 1963), pp. 197-203. On animal sacrifice among Greek and Slavic Christians see, L. Zotović, "L'egorgement rituel du tarueau", Старинар VII-VIII (1956-1957), pp. 151-157, and Megas, "Θυσία ταύρων καὶ κριῶν ἐν τῇ βορειοανατολικῇ Θράκῃ", Καογραϕία III (1911), 45.

![]()

157

protagonist of the drama, the Kalogeros, is very probably descended from the tauric Dionysios, and like him is born, killed, and reborn. The drama is accompanied by ceremonial plowing, sowing, phallic phenomena, panspermia, [12] the liknis, [13] sympathetic magic to induce rain, and magical obscenities drawn from the category of the sexual organs. Though the description of these cult practices comes from modern observations, Byzantine chroniclers testify to the existence of the Anastenarides in the 12th century and the pre-Christian Dionysian character of many elements has been accepted by Nilsson, Dawkins, and other scholars. [14]

Of no less concern than fertility, to the peasant, was health. The practice of dedicating silver or gold likenesses of parts of the body, which have been cured, to the saint's icon in the church is assuredly one of the most common sights in Orthodox churches. These tamata are not new with Christianity, however. The practice goes back to the cult of Aesclepius, and indeed the American excavations at ancient Corinth have discovered a whole series of body parts dedicated in the temple of Aesclepius. The Christian peasant continued to practice incubation in churches just as his pagan ancestors had incubated in pagan shrines. [15]

The Orthodox calendar contained not only feast days of a Christian nature but a great many which were only superficially Christian. The change of seasons was so intimately associated with agrarian, pastoral, and maritime life that the old magical practices which insured society persisted. On December 4, the feast day of St. Barbara, the Orthodox Christians offered kollyva, kollyvozomon, or melitopitta to the saint in order to assure a good crop in the next year, and to safeguard the flocks of the farmers. This is frequently referred to as varvara or varica and is

12. On Panspermia, Nilsson, op. cit., pp. 30-31, 38.

13. The liknis, associated with the cult of Dionysios, was a sieve which contained various fruits and a phallus: Dawkins, "The Modern Carnival in Thrace and the Cult of Dionysios", Journal of Hellenic Studies XXIV (1906), 191-206. Nilsson, The Dionysiac Mysteries of the Hellenistic and Roman Age (Lund, 1957), pp. 21-37.

14. The best and most detailed description of all these is Kakoure, Διονισοακά (Athens, 1963), but her conclusions and analyses should be controlled by the reviews of Megas in Λαογραϕία XXI (1963-1964), pp. 616-624, and Kyriakides, Ἑλληνικά XIX (1966), pp. 131-143. A. J. B. Wace, "Mumming Plays in the Southern Balkans", Bulletin of the School at Athens XIX (1912-1913), pp. 248-265, found differing versions of these plays among Greeks, Bulgars, Vlachs, Albanians, and Gypsies. Dawkins, "A Visit to Skyros", Bulletin of the School at Athens XI (1904-1905), pp. 72-80. For a detailed description of Dionysiac religious elements in antiquity: Nilsson, Geschichte der griechischen Religion, 3rd. ed. (Munich, 1967), I, pp. 564-601.

15. M. Hamilton, Incubation or the Cure of Disease in Pagan Temples and Christian Churches (London, 1906).

![]()

158

common to Serbs, Greeks, and Bulgars, though not to Croats. It is the ancient panspermia offered, usually, to the gods of fertility, to the souls of the dead, and to Dionysios on the third day of the Anthesteria. [16]

The most pronouncedly pagan of these Christian holidays is the cycle of Christmas and the Duodecameron which terminates with the celebration of Christ's baptism on January 6. December 25, as the supposed birth date of Christ, was not celebrated until the 4th century. Prior to that time it was a great pagan holiday, the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti. The choice of December 25, as the birthday of Christ, had as a consequence the superimposition of yet another Roman celebration, that of Calends. Thus this major celebration, which in the Orthodox calendar lasted for twelve days, was more pagan than Christian. It was a period when the mischievous Kalikantzari roamed the streets, jumping upon the shoulders of passers-by and seeking to enter houses through the chimneys. Kollyva, or panspermia, were offered to the dead and to the water spirits, fertility mimes and ceremonial renewal of the waters were performed in order to assure a prosperous New Year. The Duodecameron ended with the blessing of the waters by the priest who hurled the cross into rivers, sea, or wells, after which the cathartic powers of the waters were utilized to cleanse contaminations from the peasants' tools, icons, and other objects. [17]

Since Gibbon's time one of the most firmly rooted misconceptions among historians, about Christianity, was that it replaced the golden measure of reason and logic which alone swayed the ancient Greeks, with rampant superstition and a pathological infatuation with chres-mology or oracle mongering. However most of this superstition which we find among Orthodox Christians is the legacy of the pagan past. M. Nilsson, in his study of ancient Greek religion, was emphatic on this point.

The general opinion is that the Greeks of the classical age were happily free from superstition. I am sorry that I am obliged to refute this opinion. There was a great deal of superstition in Greece, even when Greek culture was at its height and even in the center of that culture, Athens. [18]

16. Megas, op. cit., pp. 32-34. Schneeweis, op. cit., pp. 110-111. Nilsson, Greek Popular Religion, pp. 30-31, the panspermia or pankarpeia is among the most long-lived religious practices in the Balkan area, and its existence can be documented from classical antiquity, through the medieval period, to the present.

17. Megas, op. cit., pp. 45-79. Schneeweis, op. cit., pp. 112-113. This is reminiscent of the Plynteria during which the ancient Athenians washed the statue of Athena.

18. Nilsson, op. cit., p. 111. The destruction of Athenian power in the Peloponnesian War was due, in part, to the superstition of the general Nicias during the Syracusan expedition.

![]()

159

Oracle mongers were, in the medieval as well as in the ancient period, one of the most important phenomena of religious life on the lower level. [19]

Of cult practices the most widespread and deeply rooted were hagiolatry and iconolatry. Both had strong connections with the pagan past. Hagiolatry bears many of the characteristics of the ancient hero cult and of polytheism. It is unimportant whether a particular saint can be derived from a particular hero or god, and I suspect that most attempts to trace such a derivation would be fruitless. Rather the similarity lies in the similarity of typology and function, and in the fact that both cults satisfied the same needs. The saint was above all a local religious figure whose cult usually centered about his relics. He was the immediate power to whom the needy could appeal, and very often he acquired certain specialized powers. Closely associated with the cult of the saints was that of the religious image. The icon, at least in terms of its function, replaced the pagan statue, and the miracles and magic which it was believed to perform were no less wonderous than those attributed to the statue. One church father had objected to the icon on the grounds that "if one allows pictures, then paganism does the rest". [20]

The discussion has focused primarily on the pagan survivals in rural society, for Christianity attained its earliest expansion in urban society. But in closing this discussion of paganism in Christianity I should like to mention briefly the longest-lived pagan feature of Orthodox urban life, the religio-commercial panegyris. According to Nilsson the panegyris came into being when the ancient Greeks began to experience urbanization and industrialization. From that time until the modern era, the panegyris (common to Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgars under that name) remained essentially a religio-commercial phenomenon. [21]

Balkan folk Christianity in the late medieval period represents a syncretism of magic, animism, monotheistic dogma, polytheistic prac-

19. Though the contents of this prophetic genre were influenced by Biblical material and by the changing facts of successive historical events, the form was the same. See S. Kougeas, " Ἕρευναι περὶ τῆς ἑλληνικῆς λαογραϕίας κατὰ τοὺς μέσους χρόνους. Αἱ έν τοῖς σχολίοις του Ἀρεθα λαογραϕικαὶ εἰδήσεις", Λαογραϕία IV (1913), p. 262, on the continuity of late ancient and Byzantine chresmology wherein he documents the continuity between the pagan and Christian inhabitants of Paphlagonia.

20. E. Kitzinger, "The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm", Dumbarton Oaks Papers VIII (1954), pp. 83-150.

21. Nilsson, op. cit., pp. 84-100. P. Koukoules, Βυζαντιντινῶν Βίος καὶ πολιτισμός, (Athens), III, pp. 270-283. For the panegyris during the Ottoman period, R. Brunschvig, "Coup d'oeil sur l'histoire des foires à travers l'Islam", Recueils de la société Jean Bodin, V (1953), 65-72. C. Jireček, Staat und Gesellschaft im mittelalterlichen Serbien. Denkschriften der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, vol. LVI, iii (1913), pp. 55-56.

![]()

160

tices, monism and dualism. [22] Christianity succeeded in destroying or effacing the major gods and in replacing them with a triune surface. But underneath this surface the old spirits and forces retained their grip on the masses. The folk religions of the various Balkan Orthodox peoples display many common elements (as well as divergences). Taking as a model the technical language of Balkan linguistics one might refer to these similarities as religious Balkanisms. They arise from the fact that the religious life of these peoples passed through a number of identical historical stages and was subjected to periods of common political rule, i.e., Indo-European paganism, the Roman-Byzantine-Ottoman Empires, Christianization and eventually Islamization. Thus there was a variety of manner in which similar religious practices spread over the Balkans.

Islam

From that time in the 11th century when the Seljuk rulers acquired their legal position within the political world of the declining Abbasid caliphs until the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in Europe, the Turkish sultans adhered formally to Sunni Islam. Consequently the formal religious structure with its muftis, cadis, medresses, and mosques was the instrument of Sunni Islam. However the elements of religious heterodoxy and heresy were perhaps more widespread in Turkish Islam than in Balkan Christianity at the time of the Turkish invasions of the Balkan peninsula. This was in part due to historical and political factors and above all to the emergence of the parareligious institution of the dervishes. Unlike Christianity, where monasticism had long ago been incorporated within and closely regulated by the Christian church, the dervish brotherhoods sprouted over the whole Islamic world, like so many mushrooms after a heavy rain, without any centralized control or regulation of their growth and development from the Islamic religious institution. Their widespread popularity and close knit organization over wide areas made of them indispensible adjuncts to both Islam and the sultans in Asia Minor and the Balkans. Because they ultimately appealed to the rural and urban masses, they had to satisfy those same basic passions and needs which we saw in the case of pagan survivals in Balkan Christianity. Consequently much of dervish religiosity is in essence popular religion. This dervish religious life, as it had developed in Turkish Anatolia up to the 15th century, consisted largely of mystical doctrines, popular superstitions and beliefs which errant dervishes had brought from Persia, Iraq,

22. Filipović, loc. cit., passim.

![]()

161

India, and Syria. In spite of the pronounced unorthodoxy of such orders, certain of them received great economic, social, and political support of the sultans who found in them essential colonizing and socially cohesive elements. The close association of the Bektashis with the Janissary corps, and of the Mevlevis with court ceremony of the sultans are but two manifestations of the formal recognition of heterodoxy by the Ottoman state.

More disturbing to the sultans was the shiism of many Anatolian tribes, for with the rise of the shii dynasty of the Safavis just to the east of Anatolia, religious heresy became equivalent to political subversion and revolution. Though much of the dervish religiosity which the sultans tolerated was as far removed from Sunni Islam as shiism, nevertheless it had not the same political implications, and so the sultans of the 16th century attempted to repress shiism with severe measures.

It was also the strength and persistance of nomadic life among the Turks which made of Islamization a superficial religious phenomenon among the tribesmen for a long time. The survival of shaman elements among the tribesmen, depending as it did upon the age old concern for fertility of flocks, and war-like virtues to assure pastures and survival against other foes, was assured so long as the nomadic polity continued. The tribal religious baba, usually in dervish form, was in fact the old tribal shaman who communicated with the supernatural forces and constrained them. Among the more spectacular pagan survivals from this shaman past was human sacrifice associated with the warrior cult and to which both John Cantacuzene and Chalcocondyles clearly refer. Mummification of the dead seems to have been widespread as also the belief that the soul of the dead took the form of an insect or bird. We read of Tatar-Mongol tribesmen in Anatolia who were Bhuddists, and of Chagatays who had elaborate cults and idols dedicated to the productivity of their flocks. [23]

The conversion of tribesmen to Islam and their eventual sedentariza-tion no doubt brought many of these elements into the popular version of Turkish Islam. Similar was the effect of the conversions of Anatolian Greeks, Armenians, Georgians, and Syrians. The majority of the Anatolian Christians were converted to Islam between the 11th and 15th

23. John Cantacuzene, "Contra Mahometem Apologia", in Patrologia Graeca, CLIV, p. 545. Chalcocondyles, ed. Bonn, 348. On the shamanist background of human sacrifice, J.-P. Roux, La mort chez les peuples altalques anciens et médiévaux d'après les documents écrits (Paris, 1963). See also A. Inan, Tarihte ve bugün şamanizm materyaller ve araştirmalar (Ankara, 1954), pp. 176-200. F. Köprülü, Influence de chamanisme turco-mongol (Istanbul, 1929).

![]()

162

centuries and their mass entry resulted in the further variegation of Islamic popular religion as the converts brought with them many of their own pagan and Christian practices. The genesis of Turkish Islam is thus as complex as the ethnogenesis of the Turks themselves.

Turkish Islam, when it appeared in the Balkans, represented a bewildering array of variations, perhaps more so than Balkan Christianity. The Turks converted to Islam later than the Balkanites embraced Christianity, so they were much closer to their pagan religious life. Even after conversion they retained nomadism to a significant degree and for extensive periods, hence they were only superficially Islamized. They had travelled through many lands, i.e., central Asia, Iran, Iraq, Azerbaidjan, Syria and Anatolia. Finally they represented an ethnic group which was in a constant and often violent state of ethnogenesis, absorbing other central Asiatic and Near Eastern tribal groups, as well as sedentary Persians, Arabs, Georgians, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews.

II. THE BASIC RELIGIOUS TRANSITION FROM CHRISTIANITY TO ISLAM

On the eve of the Ottoman invasions the number of Muslims to be found in the Balkans was practically non-existent. They were to be found primarily in Constantinople, where they had their own quarter and mosque, and possibly in a few other commercial towns. There was also a number of Turks, primarily Gagauz and Tourkopouloi, who had adopted Christianity and were centered in the Dobrudja and in the diocese of the Vardar Turks. However two centuries later, in the census of the taxable hearths which the Ottomans prepared between 1520-1530, there were 194,958 taxable Muslim hearths, 832,707 taxable Christian hearths, and 4,134 taxable Jewish hearths. [24] Though this census is not absolutely accurate it nevertheless gives us a faithful picture of Balkan demography in the early 16th century. 18.8% of the population was Muslim, 80.7% Christian, and 0.5% Jewish. The Turkish historian Omer Barkan has done us the great service of bringing together the demographic figures for the twenty-eight Ottoman Balkan provinces and for twelve of the more important towns. Of the 194,958 Muslim hearths, 165,980 or 85% were to be found in only ten of the twenty-eight

24. For the figures which follow, O. Barkan, "Essai sur les données statistiques des registres de recensement dans l'empire ottoman aux XVe siècles", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient I (1958), pp. 7-36. "Tarihi demografi arastïrmalarl ve osmanll tarihi", Türkiyat MecmuaslX (1952-1953), pp. 1-26.

![]()

163

Balkan districts, and the remaining 15% were scattered throughout the other eighteen districts. They were most numerous in the districts of Pasha (66,684 hearths), Silistria (17,295), Bosnia (16,935), Tchirmen (12,686), Trikala (12,347), Vize (12,193), Nikopolis (9,122), Herzegovina (7,077), Kustendil (6,640), and Gallipoli (5,001). They formed a majority of the population in only four of these districts : Silistria (72 %), Tchirmen (89%), Vize (56%), and Gallipoli (56%). They constituted between 20-46% of the population in six districts, and in twenty districts they were less than 20% of the population. From these statistics it emerges that the Muslim element was most numerous in Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Silistria. It was very sparse in Serbia, central Bulgaria, Albania, Montenegro, Epirus, Acarnania, Eubeoa-Attica, Morea and the islands.

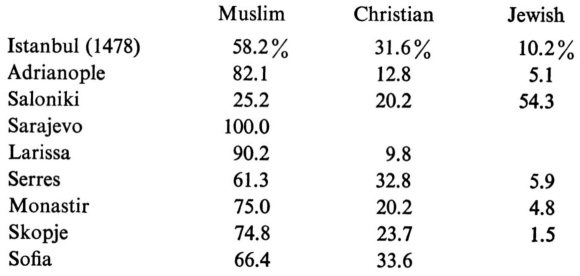

A glance at the figures for twelve of the more important Balkan towns will help sharpen our focus on demographic concentration of Muslims. Barkan's figures are far less satisfactory here, for many towns are not included, and consequently we should approach these figures with greater reservation. In nine towns the Muslims outnumbered the Christians. The ratios for the nine towns are as follows:

[[ Istanbul (1478), Adrianople, Saloniki, Sarajevo, Larissa, Serres, Monastir, Skopje, Sofia. Muslim, Christian, Jewish ]]

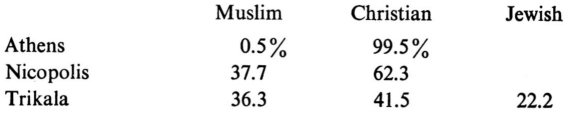

In only three of the twelve were the Christians more numerous than the Muslims:

[[ Athens Nicopolis Trikala. Muslim, Christian, Jewish ]]

Thus Islamization and demographic change are more spectacular in the towns than in the countryside in the early 16th century. By way of

![]()

164

example, the town of Sofia had a Muslim majority of 66.4%, whereas the district of Sofia was only 6% Muslim. Adrianople with a large Muslim majority (82.1%) was located in a district which had 74% Christian and 26% Muslim habitation. Sarajevo had a 100% Muslim population, whereas Bosnian Muslims constituted 46% of the population. Larissa had 90.2% Muslims, but the kaza of Trikala, in which the town was situated, had only 17.5% Muslim population. Skopje was 74.5% and Monastir 75% Muslim, and yet the kaza of Kustendil was only 10.5% Muslim. Though the Muslim population was most heavily concentrated in Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Silistria, it was most marked in the towns which constituted the administrative, commercial, and communication centers. It was from these centers that the forces of Islam radiated into the adjacent countryside and along the main routes.

One must deal with the perplexing question of the origins of this Muslim population in the Balkans at the time of the census of 1520-1530. The Muslim element had, of course, a double origin: Colonization of Muslims from outside the Balkans, and conversion of Christians and Jews within the peninsula. As yet we do not know what proportion of the entire Balkan Muslim population each of these two groups represents, for records of colonization and conversion from these two centuries of Ottoman rule are sporadic and incomplete. [25] However, a study of the hearth figures from the early 16th century provides a concrete starting point which may lead to an approximate solution or at least to an understanding of this question. In the census of 1520-1530 there are 37,435 nomad hearths of a total of 194,958 Muslim hearths, that is to say approximately 19% of the Muslim population in the years 1520-1530 consisted of nomads. This 19% represents an element which originated outside the peninsula and therefore belongs to that category of Muslim population which came as a result of colonization.

What was the origin of the remaining 81 % of the Muslim population? The two principal authorities on the nomads and colonization, Gökbilgin and Barkan, have attributed a great, indeed a major, role to the nomads

25. On colonization one may consult the following : Barkan, "Les deportations comme méthode de peuplement et de colonisation dans l'Empire Ottoman", Revue de la Faculté des sciences économiques de l'Université d'Istanbul XI (1949-1950), pp. 67-131 ; A. Decei, "Etablissement d'Aktav de la Horde d'Or dans l'Empire Ottoman au temps de Yïldïrïm Bayezid", Zeki Velidi Togan'a Armagan (Istanbul, 1950-1955), pp. 77-92; M. Gökbilgin, Rumeli’de Yürükler, Tatarlar ve Evlâd-i Fâtihân (Istanbul, 1957); D. Angelov, "La conquête des peuples balkaniques par les Turcs", Byzantinoslavica, XVII (1956), pp. 263-275.

![]()

165

in the Muslim colonization of the Balkans. According to these scholars the social organization and mobility of the nomads, as well as the desire of the sultans to place them in an environment where they would be less troublesome, made of them a primary source for colonists. It is, nevertheless, difficult to find any systematic confirmation or refutation of this proposition in the sources. If it is true that the nomads were so significant, numerically, in colonization then the figure of 37,435 hearths may indeed be an important clue in ascertaining the proportion of Muslim colonists to converted Balkan Muslims. [26] It has emerged from the study of the Ottoman documents of the 16th-17th centuries that these Yürüks and Tatars preserved their nomadic status throughout the 16th century, undergoing basic sedentarization only in the 17th century. Undoubtedly some nomads were sedentarized earlier, and their appearance in the hearth census among the sedentary Muslims who constituted 81% of the Muslim population would obscure the question of their origin via nomadic colonization. However the survival of the nomadic system, as reflected by the Ottoman documents, would indicate that large scale sedentarization began to affect the nomads only in the 17th century. One might therefore assume that the majority of the Yürüks and Tatars remained in their nomadic status as of the census of 1520-1530, and that the 81% of the sedentary Muslim population contained only a small element of sedentarized nomads.

In addition to the migration of nomadic groups there is some general evidence that sedentary Muslim elements came from Asia Minor to the Balkans, some seeking farm lands, others military and administrative service, while still others came to establish the religions institutions of Islam. Undoubtedly a good portion of this element came as a result of specific colonization policies, whereas another segment crossed to Europe under the impact of the Timurid invasions and other upheavals. There is less specific information on the sedentary Muslim element in the colonization of the Balkans. But if we should accept the proposition that the nomads actually constituted a major source of colonists we arrive at the following interesting proposition: Perhaps 50% of the Balkan Muslim population of 1520-1530 had their origins (whether nomad or sedentary) in colonization from outside the peninsula. Thus, if one assumes that the nomadic 19% represents a very substantial proportion of the original colonizing element, that the majority of the nomads did not undergo major sedentarization prior to the 17th century, and that the ratio of

26. This does not answer such questions as the comparative rate of growth among settled and nomadic peoples.

![]()

166

population reproduction between the sedentary and nomadic Muslims up to the early 16th century was not too different — if these propositions, based on the nomadic figures, are actually valid (and here I emphasize the propositional character of this sequence of reasoning), then it would follow that a large proportion of the sedentary Muslims in the Balkans had their origin in religious conversion. If all this is true, then we are dealing with a significant movement of Islamization, significant primarily in terms of the genesis of the Muslim Balkan population.

There are both general and specific indications that this conversionary process was effective throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule. The very conquests were accompanied by Islamization, in varying degrees, throughout the peninsula, a fact which dismayed the first Orthodox patriarch after the capture of Constantinople by the Turks. [27] Though the Muslim rulers and religious men tolerated Christianity formally, and allowed the patriarchate to be resurrected after its temporary demise in 1453, the condition of the church prior to 1453 was anomalous. The Christian Empire and the Orthodox Church were inextricably intertwined prior to 1453, and as the Christian Empire was the principal foe of the sultans, the Orthodox church and bishops were politically suspect in Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, and in other areas conquered before 1453. Consequently the church suffered economic impoverishment and administrative disruption in many of these areas prior to the reunification of all Orthodox lands under Turkish rule and until the resurrection of the patriarchate as a department of state in the new empire. The Turks removed the metropolitans from such sees as Adrianople, Serres, and Maeroneia, confiscated much of the church property, and gave the majority of these confiscated properties and serfs to the Muslim timar and waqf institutions. [28] The Ottoman administrative and religious institutions seem to have welcomed Islamization, and indeed contemporary observers describe the celebrations and joy which conversions of dhimmis

27. A. Vakalopoulos, Ἱστορία του νέου Ἑλληνισμοῦ, II1 (Thessaloniki, 1964), pp. 149-150. P. Petrov, Асимилаторската политика на турските завоеватели. Сборник от документи за помохамеданчвания и потурчвания (XV-XIX в.) (Sofia, 1964), pp. 19ff.

28. Both the Turkish and Byzantine sources are in agreement on this point. Gökbilgin, XV-XVI asĭrlarda Edirne ve Paşa Livâsĭ. Vakĭflar-mülkler-mukataalar (Istanbul, 1952); F. Miklosich et I. Müller, Acta et diplomata graeca medii aevi sacra et profana (Vienna, 1860-1862), I-II; C. Amantos, "Zu den Bischofslisten als historischer Quellen", Akten des XI. Internationalen Byzantinistenkongresses, München, 1958 (Munich, 1960), pp. 21-23; G. Ostrogorsky, "La prise de Serres par les Turcs", Byzantion, XXXV (1965), pp. 309-310.

![]()

167

occasioned. [29] The proselytizing spirit was perhaps most pronounced among the dervish orders, of whom the Bektashis and Mevlevis had already displayed remarkable success among the Orthodox Christians of Anatolia. These brotherhoods remained important conversionary instruments in the Balkans until early modern times. The administrative and military apparatus was an important channel of conversion, as is well known. The Janissaries and gulams of the palace service were the most spectacular aspects of government-sponsored conversion. [30] But conversion was also evident among the Christian spahis of the 15th-16th centuries, who frequently must have brought their serfs into the folds of Islam with them. The Christian naval personnel of Gallipoli eventually converted to Islam, as did many of the court and local scribes, tax farmers, and guildsmen. [31] Intermarriage, primarily between Muslim males and Christian women, had a long and fascinating history. [32] Finally there were instances of conversion under duress and the related phenomenon of Crypto-Christianity. [33]

The reasons for conversion may, I think, be reduced to three basic ones. First there were the very real or material advantages which would ensue upon religious conversion. A change of religious status meant, in effect, a basic movement in society from an inferior to a superior class. As members of the triumphant religion, Muslims enjoyed a lighter tax burden and a favored legal position in all their economic and social relations in the eyes of the courts which judged these relations. In this respect one need only recall that the testimony of a Christian was inadmissable as evidence in a Muslim court. [34] Second there was the success-

29. Schiltberger and Bartholomaeus Georgiewitz give a clear picture of the proselytizing spirit as it affected much of Ottoman society.

30. Vryonis, "Seljuk Gulams and Ottoman Dervishes", Der Islam XLI (1965), pp, 224-252.

31. H. İnalcik, "Stefan Dusan’dan osmanlï imparatorluğuna. XV. asĭrda Rumeli’de hĭristiyan sipahiler ve menşeleri", in Fatih devri üzerinde tetkikler ve vesikalar, I, (Ankara, 1954), pp. 137-184. Djurdjev, "Bosna", EI2 S. Skendi, "Religion in Albania during the Ottoman Rule", Südost-Forschungen XV (1956), p. 314. Inalcik, "Gelibolu", EI2. H. Duda and G. Galabov, Die Protokollbücher des Kadiamtes Sofia (Munich, 1960), passim.

32. N. J. Pantazopoulos, Church and Law in the Balkan Peninsula during the Ottoman Rule (Thessaloniki, 1967).

33. Dawkins, "The Crypto-Christians of Turkey", Byzantion VIII (1933), pp. 247-275. P. Karlin-Hayter, "La politique religieuse des conquérants ottomans dans un texte hagiographique (c. 1437)", Byzantion XXXV (1965), pp. 353-358. On forced conversion and on the execution (by burning) of those who refused to convert, H. Dernschwamm's Tagebuch einer Reise nach Konstantinopel und Kleinasien 1553-1555, ed. Babinger (Munich-Leipzig, 1923), pp. 11, 140-141.

34. M. Grignaschi, "La valeur du témoinage des sujets non-musulmans (dhimmi) dans l'empire ottoman", Recueils de la société Jean Bodin, XVIII (1963), pp. 211-323. On the tax differences: İnalcik, "Osmanlĭlar’da raiyyet rüsûmu", Belleten XXIII (1959), pp. 575-610.

![]()

168

ful appeal of religious preaching and social ministration of Muslim dervishes, medresses, mosques, and imarets. These combined effective preaching with the economic affluence assured them by the fact that the Ottoman state was Muslim. Finally, there was the element of fear, particulary in stressful times, which predisposed various Christian groups and individuals to convert. Conversion to Islam was a finality, for conversion, or reversion, to Christianity and Judaism was punishable by death. [35]

Islamization continued as a significant process of cultural change for three centuries after the census of 1520-1530. Albania is the most spectacular case in this respect, for in the years 1520-1530 the kazas of Scutari and Elbasan contained Muslim populations of only 4½ % and 5½ % of their respective total populations. The timariots in the defter of 1430 were predominantly Christian Albanians. [36] The original impact of Islamization seems to have been felt in central Albania, coming to the north in the 17th century and affecting the south even later. [37] In Bulgaria Islamization is discernible in the northeast, in the border regions of Thrace and Macedonia (before the census under discussion). A new wave of Islamization, with important consequences, cocurred in 1666-1670 and 1686-1690. As a result some 74 villages in the Rhodope and other regions turned Muslim. A third wave took place in the beginning of the 18th century. These conversions seem to have been of the group variety and were occasioned by the pressures of war and accompanied by the presence of expeditionary armies and heavy tax extortions. [38] Among Greeks the Islamization of the Vallahades in southwest Macedonia and of Cretans took place in the 17th-18th centuries. The latter seems to have been primarily the work of dervishes, while the former process proceeded from the tensions following the Russo-Turkish wars. [39]

35. Nicodemus Agiorites, Νέον Μαρτυρολόγιον, 3rd ed. (Athens, 1961).

36. Barkan, "Essai", passim, İnalcık, Hicrî 835 tarihli suret-i defter-i sancak-i Arnavid (Ankara, 1954); "Timariotes chrétiens en Albanie au XVe siècle", Mitteilungen des österreichischen Staatsarchivs IV (1952), pp. 118-138.

37. Skendi, loc. cit., passim. P. Barth, "Das Bistum Sappa-Sarda in Nordalbanien nach einem Bericht aus dem Vatikanischen Archiv (ca. 1750)", Südost-Forschungen XXV (1966), pp. 27-37. G. Stadtmüller, "Die Islamisierung bei den Albanern", Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, N. F., III (1955), pp. 404-429.

38. Petrov, op. cit., p. 166, and passim.

39. P. Hidiroglu, Das religiöse Leben auf Kreta nach Ewlija Čelebi (Bonn, 1967). Hasluck, Christianity and Islam under the Sultans (Oxford, 1929), I, 8; II, pp. 474, 526-528.

![]()

169

Perhaps the most interesting case is that of Islamization in Bosnia. Though Islamization here was a significant affair it did not occur suddenly and in the beginning of Ottoman rule as some have maintained, but was more of a drawn out process. [40] A quarter of a century after the conquest (1463-1489) there were:

Christians: 25,000 hearths 1,300 widows 4,000 bachelors

Muslims: 4,500 hearths 2,300 bachelors

There were approximately five times as many Christian as Muslim hearths in 1489. However by the census of 1520-1530 the Muslim hearths numbered 16,935 and the Christian 19,619. In 1489 the Christians constituted 81.6% and the Muslims 18.4% of the population. But by 1520-1530 the number of Muslim hearths had more than tripled and the number of Christian hearths had dropped impressively. The ratio of Muslim to Christian hearths had changed to a ratio of 46 % to 54 %. Thus these statistics strongly suggest that the conversionary process was at its peak during the thirty years between the two census reports. It would also seem that though the Bogomils were in outlying, isolated districts, Islamization spread from the towns (the centers of Islam) to the immediate vicinities and finally into the rural areas. Consequently, though the factor of sectarian pluralism must still be considered in the question of Bosnian Islamization, the exact relation of Bosnian heretical life and the success of Islam in Bosnia, for me at least, remains obscure.

There is one aspect of Turkish Islam in the Balkans which is enigmatic and deserves some attention at this point. The Turkish conquerors inherited the old core lands of Byzantine culture, i.e. Asia Minor and the Balkans, and within these two peninsulas Islamization had two entirely different results. Let us return to the hearth lists of the early 16th century for a brief moment. In Asia Minor the Muslim to non-Muslim ratio was as follows: [41]

Muslim 953,997 or 92.4%

Christian 77,869 or 7.5%

Jewish 559 or 0.1%

__________

1,032,425 hearths

In the Balkans:

Muslim 194,958 or 18.8%

Christian 832,707 or 80.7%

Jewish 4,134 or 0.5%

__________

1,031,799 hearths

40. See note 1 above.

41. Barkan, "Essai", passim.

![]()

170

In Asia Minor the Muslims were a crushing majority of the population whereas in the Balkan they were a minority. How does one explain the greater success of Islamization in Asia Minor, and the mass survival of Christianity in the Balkans? At this point the historian can draw up a list of historico-social dissimilarities in the conditions of conquest of the two peninsulas and speculate as to the correlation between these dissimilarities and the differing fortunes of Islamization.

The first difference which one observes is in the length of the period of conquests in each area. The Turkish conquest of Asia Minor was characterized by longevity, the area not being completely conquered until four centuries after the first Turkish raids commenced in the 11th century. In the Balkans the conquest lasted for about one century and would have been shorter save for the Timurid interlude. Also, many of the Balkan states were first incorporated as vassal states before the final absorption into the Ottoman system.

Second, the conquest of the Balkans was effected by one strongly centralized state which soon imposed political unity on the whole area, and restored order and prosperity. In contrast, the conquest of Anatolia was a long, repeated affair, effected by several states and tribes, and transformed much of the area into a domain of war for extensive periods. Consequently destruction was much more widespread in Asia Minor than in the Balkans. The Turkish conquests of Anatolia replaced political unity with a bewildering political pluralism and the peninsula was not reunified until the 15th century. In the Balkans the Ottoman conquest replaced political pluralism with political unification.

On the level of ecclesiastical polity there was considerable difference too. Throughout four centuries of warfare and conquest in Asia Minor, the Orthodox Church of the area was closely connected with the patriarch of Constantinople, who was ultimately associated with and the instrument of the emperor, the principal foe of the Turkish conquerors. Therefore the church was politically suspect. As a result the Turks deprived it of practically all its properties, revenues, and expelled its bishops for long periods of time. In the Balkans the same pattern of economic confiscation and removal of bishops is visible in the first areas the Turks conquered. But the conquest did not last as long. Many of the regions

![]()

171

were under Turkish rule for only a few years prior to 1453, and when the Christian Empire was destroyed in 1453, the patriarch no longer had dangerous political connections. The hierarchy was revived and the church retained whatever was left of its properties, still considerable in comparison to the little property remaining to the church in Asia Minor. Consequently the Christian establishment of the Balkans did not have to suffer disruption for such long periods as in Asia Minor. Its position was regularized relatively quickly.

Demographically the bulk of Turkish settlement took place in Asia Minor rather than in the Balkans. In this regard most important were the Turkish nomads, a principal factor in the disruption of the Anatolian Christian society. It was this element which had effected much of the conquest of Asia Minor, and the sultans were able to control the nomads only during the 13th century. But when the central authority was weak, as in the 11th-12th and late 13th-14th centuries, they become independent agents, raiding and pillaging sedentary society. As a result much of the agricultural areas reverted to nomadic pastoralism. The economic life of the nomads was a further bane to the sedentary population because of their activity in the slave trade. In the Balkans the conquests operated under the control of a stricter centralized authority, and as the conquests ended the sultans exerted greater restraint and control of this particular element than had been the case in Asia Minor.

The greater disruption which the nomads wreaked in Asia Minor is related not only to the breakdown of central authority and to the existence of political pluralism, but also to the factor of their large numbers. Inasmuch as the Turks came to the Balkans via Asia Minor the greater number of the nomads was to be found in Anatolia. Though there are no figures as to the tribal numbers which came in the original conquests, the statistics which Barkan has tabulated for the early 16th century indicate clearly that the nomads of Anatolia were far more numerous than those of the Balkans. In the province of Anadolu alone (this includes central and western Anatolia, but excludes eastern Anatolia which had large tribal agglomerations) there were 77,268 nomad hearths. In the entire Balkans there were only 37,435, or slightly less than half of the numbers in central and western Anatolia. It is of further interest that the nomads of Anadolu, as also the nomads of the Balkans, constituted approximately the same proportion of the total Muslim population of their respective provinces, i.e. 19.7 % and 19 % of the total Muslim populations. But the truly significant figure in this respect was the ratio of nomad population (o the entire population (Christian, Muslim, Jewish) of each

![]()

172

area. In Anadolu the nomads constituted 16.2% of the entire population, whereas in the Balkans they constituted only 3.6% of the entire population. This is, I would suggest, a very significant factor in both the questions of Islamization and disruption.

These differing factors in the conquests of the Balkans and Anatolia undoubtedly contributed to the differing fate of Christianity and the varying fortunes of Islamization in the two peninsulas. [42]

III. EXAMPLES AND PATTERNS OF THIS RELIGIOUS CHANGE CONCLUSIONS

The statistical approach to the question of continuity and change in the religious life of the Balkans, applicable for the first time in the case of the Ottoman period, is of great value to the historian. The statistics indicate clearly the continuity of Christian religious life of the majority of the inhabitants, and a change in religious life of that minority converted to Islam. But the statistics give only a two dimensional version of this continuity and change for they present a picture, in simple black and white, of a formal religious world which contains Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Thus in the question of religious change they convey the impression that converts to Islam simply abandoned Christianity and embraced a pure Islam. This is reinforced by the vision of a Sunni Islamic religious life centered in the medresses and mosques, accompanied by namaz, circumcision, polygamy, and the adoption of Muslim names. The statistics, however, tell us nothing of the everyday details or quality of the religious life among the converts. In short the statistics do not tell whether or not the new religious life of the converts represents a complete break with their pre-Muslim religious life.

Franz Babinger, perhaps the keenest student of Balkan Islam, had contended that two religious phenomena gave Balkan Islam its real content: hagiolatry and the dervish brotherhoods. [43] These two elements, the one Christian and the other Islamic, were essentially popular religion and they appealed to both Muslims and Christians. In addition, the Ottoman conquests of the Balkans brought no overall disruption and change to the rural population's attachment to the seasonal-religio-

42. These conclusions have been developed at great length in my forthcoming book, The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization, 11-15th Centuries (University of California Press).

43. Babinger, "Der Islam in Südosteuropa", in Völker und Kulturen Südosteuropas, Schriften der Südosteuropa Gesellschaft (Munich, 1959), pp. 206-207.

![]()

173

magical calendar or to its concern for health and fertility. The continuity in this type of religious life is clearly visible in the life of important segments of the converts and demonstrates the syncretistic character of popular Islam. What were the vehicles of transmission by which elements from this pre-Muslim religiosity passed into Islam? Most important were the mass conversions which occurred among the Albanians, Bosnians, Bulgar Pomaks, and Greeks. The larger the numbers of the converted group, the more diluted was the Islam of the converts. Largeness of number served to insulate the old religious practices and beliefs from thorough penetration by Islamic practices and beliefs. Conversely, individual conversion meant that the convert would enter the body of Muslims alone, and his previous beliefs and practices would expire with him at the end of his life. One may also assume that of the sedentary Muslims of Anatolia, who came to the Balkans as colonists, some were converts or the descendents of converts who had retained certain Christian elements in their version of Islam. Wherever large scale intermarriage of Muslim males and Christian women took place, and this was of frequent occurrence, there are indications that the women were the vehicle by which much of popular Christianity passed into Islam. The syncretism of the dervish orders in equating comparable Christian and Muslim religious practices and beliefs and in outright adoption of Christian items, made of the brotherhoods the most important Muslim religious institution in the epibiosis of pre-Islamic religious customs. [44] The vitality of Christian folk culture, the importance of Christians in Ottoman agricultural, maritime, and commercial life meant that the old forces and elements which the Christians had propitiated in the past to ensure health and prosperity would now enjoy a considerable continuity.

Before passing on to a very brief examination of pre-Muslim survivals in certain areas where group conversions occurred one should note three of the more widespread religious practices which passed into Balkan Islam: baptism, animal sacrifice, and hagiolatry. The practice of baptism was already widespread among the Anatolian Muslims of Asia Minor two centuries before the Turks crossed over into Europe and there is

44. Hasluck, op. cit., passim. J. Birge, The Bektashi Order of Dervishes (London, 1937). A. Gölpinarlĭ, Mevlana’dan sonra Mevlevilik (Istanbul, 1953). Kissling, "Das islamische Derwischentum als Bewahrer volksreligiöser Überlieferung", Religiöse Volkskunde XIV (1964), pp. 157-166. The history of the family of Bedr ed-Din contains elements both of intermarriage with Christians and of intense religious syncretism between Islam and Christianity: Kissling, "Das Menaqybname Scheich Bedr ed Din's des Sohnes des Richters von Samavna", Zeitschrift der deutsche morgenländische Gesellschaft, C (1950), pp. 114-116, passim.

![]()

174

evidence that it remained important beyond the 17th century in the Balkans. A 12th century Byzantine commentator on the church canons relates that it was widespread among the Turks of Anatolia. [45]

...it is the custom that all the infants of the Muslims be baptized by Orthodox priests... For the Agarenes suppose that their children will be possessed of demons and will smell like dogs if they do not receive Christian baptism.

Many Muslim peasants believed, as did their Christian counterparts, that baptism was an effective agent against mental illness and against what they called the 'foul smell', so they employed it for its magical powers. It was still so widespread in the 17th century that a synodal decision of Constantinople threatened all Christian priests, who continued to baptize the children of Turks, with defrocking. [46]

Propitiatory animal sacrifice (thysia, kurban) is one of the remarkably stable factors in the folk religion of Greeks, Armenians, and Balkan Slavs, from antiquity until early modern times. The 16th century Croatian, Bartholomaeus Georgiewitz, who lived as a slave in Turkey, remarks upon the existence of a type of animal sacrifice among the Muslims which had apparently passed over from popular Christianity. [47]

The Manner of their sacrifice, (of the Turks)

In the time of anye disease or peril, they promise in certaine places to sacrifice either a Shepe or Oxe; after that the vowed offering is not burned, like unto a beast killed and layed on the aulter, as the custome was among the Jewes, but after that the beast is slaine, the skinne, head, feete, and fourthe parte of the flesh are gene unto the prest, an other part to poore people, and the thirde unto their neighbours. The killers of the sacrifice doo make readye the other fragmentes for the selves and their compaynions to feede on. Neyther are they bound to performe the vow, if they have not bene delivered from the possessed disease or peril. For all things with them are done condytionallye I will geve if thou willte graunt. The lyke worshyppinge of God is observed among the Gretians, Armenians, and other realmes in Asia imitating yet y Christian religiō.

The specific detail which strongly suggests the passage of this type of sacrifice from the Christians to the Muslims is the description of the apportioning of the parts of the slain animal. This corresponds exactly to the dermatikon, or the priest's share, as it is described in Greek inscriptions from Greece, the isles, and Asia Minor in antiquity. [48]

45. Rhalles and Potles, Σύνταγμα τῶν θείων καὶ ἱερῶν κανόνων, II (Athens, 1852), p. 498.

46. Koukoules, op. cit., IV, pp. 54-55.

47. Bartholomaeus Georgiewitz, The Offspring of the House of Ottomanno (London, 1570), under "The Manner of their Sacrifices".

48. See Vryonis, "Byzantium and Islam, Seventh-Seventeenth Centuries", East European Quarterly II (1968), p. 239, n. 71. "Dermatikon", Pauly Wissowa.

![]()

175

Finally, the effectiveness of the saint's powers was recognized in popular Islam, and frequently Muslims appealed to one or another of the saints. In the realm of syncretism certain Christian and Muslim saints were closely associated, enjoyed common attributes, and often one was interchangeable with another. [49] Baptism, animal sacrifice, and hagiolatry were among the most widespread borrowings of Islam from Christianity in the realm of popular religion. Baptism represents a specifically and uniquely Christian form, the particular type of animal sacrifice a classical pagan form, while hagiolatry constitutes a form which was common to both Islam and Christianity prior to the appearance of the Turks in the Balkans.

Folklorists, by their study of the Muslim Albanians, Bosnians, and Pomaks, have contributed to our knowledge of the continuity of Balkan folk religion within Islamic popular religion. It is significant that Vakarelski prefaced his study of the Pomaks by noting the survival of the old Bulgaro-Christian rural life and agricultural technology among the converts to Islam. The old magical practices associated with the harvest, threshing, sowing, survived and in this respect he observed that the old Kukeri dances and mimes associated with the Dionysiac fertility rites (and which are mentioned above) survived in some Pomak communities. In family life the Pomaks continued to believe that the Bogoro-ditsa aided the mother in the travail of birth, that the fates determined the life of the newborn child on the third night, and consequently they baked a pita for the former and left a meal behind the door for the latter on the third night after the birth of the child.

Many observed Easter by taking colored eggs from the Christians, which, they believed, would assure good health. In connection with health they brought ill children to church on Good Friday, visited the local ayasma, sought the blessing of the priest in church on feast days, and took holy water from the priest for the benefit of the family members and the livestock. They made offerings to church icons, frequently and covertly kept church books and icons in their houses, and continued to perform animal sacrifices in the courtyards of certain churches and monasteries. [50]

The converts in Bosnia, Serbia, and Macedonia similarly brought many old religious customs when they adopted Islam. Like the Pomaks they also observed Easter after a fashion by dying Easter eggs. They

49. Note 44 above.

50. Ch. Vakarelski, "Altertümliche Elemente in Lebensweise und Kultur der bulgarischen Mohammedaner", Zeitschrift für Balkanologie, IV (1966), pp. 149-172.

![]()

176

celebrated the feasts of Sts. George, John, Peter, and on the feast day of St. Barbara prepared boiled wheat or varica, the ancient panspermia. Though they adopted the Muslim marriage ceremony they incorporated certain old practices with it. Many Muslim families knew who the old patron saint of the family had been in the days before Islam and invited family friends to their house on his feast day. [51] Among the Albanian converts the visitation of churches and baptism of their children were only two of the more prominent elements which the converts brought with them. [52]

CONCLUSIONS

This brief survey of the Balkan religious configuration in the 14th century, of the extent of Islamization during the following two centuries, and of the patterns and examples of religious change, lead to the following conclusions.

(1) At the time of the first Turkish invasions of the Balkans, paganism was a very marked characteristic of Balkan folk Christianity and shamanism of nomadic Islam.

(2) Though the Anatolian Christians largely succumbed to Islam, Islamization remained a peripheral phenomenon in the Balkans as a whole. The differing fate of Christianity and Islam in the two peninsulas was due primarily to the differing circumstances of the Turkish conquests in the two areas.

(3) Though the Islam which emerged in the Balkans was 'orthodox' on the formal level, on the popular level it was heavily influenced by the ancient pagan and Christian elements which the converts retained after their conversion. Consequently, though the entrance of the Turks and their long rule mark a real epoch in the history of the Balkan peoples, the changes which they wrought in the religious life of the Balkan masses were restricted. The majority of the Balkanites did not convert, and even those who did so retained a great deal of their pre-Islamic religious beliefs and practices. Thus, in spite of the religious change which accompanied Ottoman rule, continuity was the dominant feature of Balkan religious life in this period.

51. Schneeweis, op. cit., pp. 146ff. and passim.

52. Barth, loc. cit., p. 31.