The Communists

Confused former national romantics – nationalistically oriented

in their views and convictions on the question of national unification,

children from the prewar [Nationalist] Yugoslav Youth who were perishing

as guerrillas on Balkan battlefronts, wild individuals of social-revolutionary

orientation who saw no difference between anarchist terror and the mass

movement, the rebels of Odessa, anarcho-individualistic literati, old Serbian

routineer politicians whose ambitions were disproportionately greater than

their subjective capabilities... new dissidents of Yugoslav [Nationalist]

Youth who were leaving terroristic royalist organizations, a fair number

of university trabants from various political groups, and very few proletarians

– manual workers, those were the elements that made up the first phalanx

of our leftist movement.

Miroslav Krlezha, 1935

It might seem odd that the members of Yugoslavia's early Communist

movement should be grouped alongside the opponents of centralism and unitarism,

the Communists being among the most eager supporters of those policies.

Nevertheless, no group seethed in greater agitation against the post-1918

Yugoslav system than the Communists, and its large following was mainly

among the nationally disaffected.

The history of indigenous communism in Yugoslavia during the first years

of the first Yugoslav state is one of great strides and sharp reversals.

[1]

The Unification Congress of the Komunisticka partija Jugoslavije (KPJ,

Communist Party of Yugoslavia), or of the Socijalisticka radnicka partija

Jugoslavije (komunista) (SRPJ[k], Socialist Workers' Party of Yugoslavia

[Communist]), as the party was called until June 1920, marked the end of

the first phase in the consolidation of the Comintern's South Slavic section.

Despite its considerable successes, the KPJ was not destined to become

a compact entity during its two years of legality. As a result of being

forced underground in 1 92 I, the party was decimated. In the next decade

and a half, though it increasingly bent to the requirements of Moscow,

it was at the same time weakened internally by factionalism. Thus, though

it was saddled with the ballast of Russism (less a discredit in Yugoslavia

than in the other East European countries), it did not, until Tito's advent

in 1937, have anything like the discipline of the Moscow central party.

The KPJ itself was an uneasy combination of independent leftists, many

of them, at least in the former Austro-Hungarian territories, from the

ranks of the Nationalist Youth, and of Social Democratic groups, whose

various traditions and stands on the national question were discussed in

Part II. At the Unification Congress (Belgrade, April 20 – 23, 1919) the

party was clearly under the great influence of Srpska socijaldemokratska

partija (SSDP, Serbian Social Democratic Party), which joined the new Communist

movement en masse and gave it a direction that was wedded to certain orthodox

– but not quite Bolshevik – traditions of old Serbian Social Democracy.

The centrist faction, at equal distance from the Communist left and the

reformist traditions of Social Democracy, was defeated at the Second Congress

(Vukovar, June 20 – 24, 1920), at which point the party largely assumed

its familiar ideological contours. Most of its energies were devoted to

militant trade-union action, the peasant and national questions being largely

ignored. Nevertheless, at the elections for the Constituent Assembly in

1920, the KPJ gained 198,736 votes, or fifty-nine seats, ranking fourth,

after the ruling Democratic and Radical parties and the oppositional HPSS,

in ballots cast.

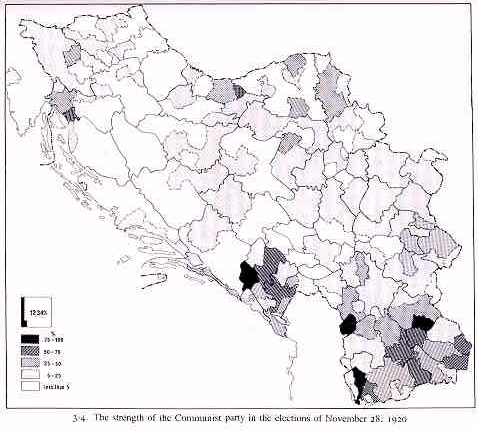

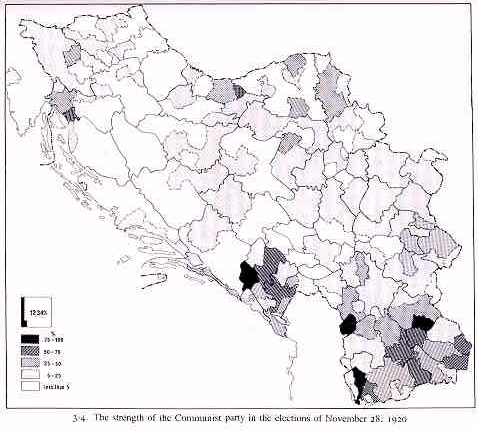

Most of the Communist votes (see map 3-4) came from Montenegro, Macedonia,

Kosovo, and Metohia, the showing in Montenegro being most impressive (37.99

percent of the ballots cast). But in the more industrialized areas, such

as Slovenia and Croatia-Slavonia, the KPJ polled 10.29 and 7.13 percent,

respectively, below its statewide average of 12.34 percent. Its performance

was not exceptional in the major industrial cities (Osijek, 26.73 percent;

Zagreb, 24.64; Ljubljana, 17.04; Maribor, 14.03; Sisak, 13.52; Varazhdin,

10.54; Celje, 0.75), though it did very well in some other urban centers

(Split, 35.7 percent; Subotica, 34.62; Belgrade, 32.25) and overwhelmed

certain industrial zones (the Trbovlje mining region in Slovenia, 66.42

percent). On the whole, however, the KPJ's successes cannot be accounted

far in terms either of the base that the Communists appealed to or class

orientation. In Macedonia and Montenegro, where the KPJ had its most impressive

successes, there were no organized national parties that could wage legal

struggles against centralism and Serbian hegemonism. The KPJ's good fortune

in these areas was an electoral protest against the regime. As an avowedly

revolutionary party, the KPJ was the only outlet for the recusant nationalities

in these areas. In the other areas of intense national disaffection, such

as Croatia-Slavonia, Slovenia, and Bosnia-Hercegovina, the non-Serbs generally

voted for the parties that best represented their national and confessional

interests: the Croats for Radic's HPSS, the Slovenes for the Slovene People's

Party, and the Bosnian-Hercegovinian Muslims for the Yugoslav Muslim Organization.

Here the KPJ's showing was less impressive, Nevertheless, the KPJ still

tended to discount the strategic potential of the national question and

made no attempts to capitalize on this issue. The Communist leaders were

overconfident of their ability to ride the continental red wave, and not

inclined to reexamine their position.

Subsequent events repudiated the stance of the KPJ leadership. The postwar

revolutionary wave in Europe had already reached its peak and was visibly

receding. The defeat of the Red communes in Germany and Hungary and Soviet

reversals in Poland hastened the stabilization of the anti-Communist governments

and the social order that they safeguarded. But in Yugoslavia, where peasant

insurgency was still seething – as in Croatia in 1920– the KPJ failed to

appreciate the importance of national and peasant movements and lost the

opportunity to impose itself on the rebel peasants. The Communist deputies

in the Constituent Assembly, though seemingly confident, hardly appreciated

the resilience of the regime that they continued to attack with an assortment

of rhetorical devices. Nor did the KPJ leadership recognize the extent

of the party's isolation, widened by the Communist inability to differentiate

between the centralist government and the opposition parties. In the long

run, the revolutionary bravado, as yet untested in direct conflict, proved

counterproductive and exposed the party to government reprisals.

. . .

[Back]

1. This section is greatly expanded

in my work "The Communist Party of Yugoslavia during the Period of Legality

(1919 – 1921)," in Ivo Banac, ed., The Effects of World War I: The Class

War after the Great War; The Rise of Communist Parties in East Central

Europe, 1919 – 1921 (Brooklyn, 1983), pp. 188 – 230. This work includes

the most up-to-date bibliography of studies on the early history of Yugoslav

Communism.