PART I. BULGARIA, 1903.

CHAPTER I.

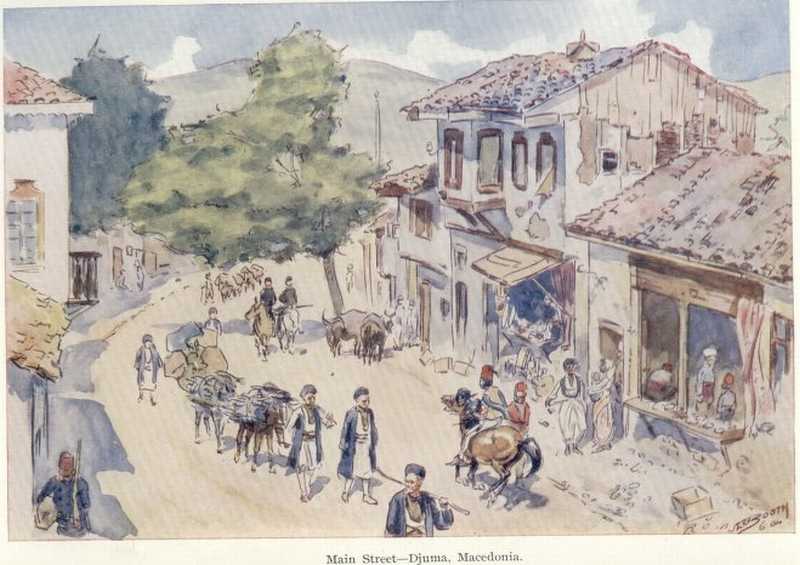

We yearned beyond the sky-line where the strange roads go down.

"PUTTIES, shooting-boots, spurs (h'm one strap broken), pistol, ammunition, sketch-books," and so forth, down a pencilled "list of kit," as the objects mentioned (barring the broken strap) were fitted scientifically into a sturdy brown kitbag - a dear old travelled thing, with a patch at one corner put on at Ladysmith. The studio was thick with tobacco smoke, and the autumn sun, filtering through the top-light, lit and glinted on small piles of the indispensables of a man preparing for rough times in the open. Out of the corner by the fire a newspaper rustled jerkily, and a voice observed: "Say, there's hell to pay in Raslog. Here's a Reuter wire says insurgents attacked Turks near the village of How-d'ye-callit, and Turks afterwards entered village an' massacred all hands. People burnt at the stake

![]()

2

an' a real hot time all round. An' here's Laffin'an'-Jokin' says negotiations broken off an' war considered inevitable. Whoopee! boy, if we can't get our throats cut this time you can call us slow!"

All summer the Sultan's troops had been amusing themselves on the above lines, and now it seemed that Bulgaria was going to strike a blow for her fellow-Christians over the border. This cheery prophet in the corner - yachting ten days before at North-East Harbour, U.S.A. - had fired himself across the Atlantic, spurred by some such news as this, and "coming up with a song from the sea" found me in the final stages of "go-fever," the only cure for which is - to go. So together we rushed to newspaper offices, whose comfortable inhabitants predicted a lingering and untidy death and rashly entrusted us with the supply of a little news from the Balkans - the good old Balkans, where there's always something doing. So the kit was packed, the old studio locked up, and we rolled away under the Victoria signals, "pulling out on the trail again." And now, suddenly, the enclosing walls of the London life fell away from us, and dwindled, with all that was written on them, to littleness and unimportance. One's mind looked from a balloon and saw shops, 'buses, Tuppenny Tube, offices and editors as tiny things in an ant city. Nothing behind mattered. Everything important lay in that vague country ahead, pictured already in imagination. Two hours later, great-coated and hands in pockets, we were on the wet deck of the Flushing steamer, leaning against

![]()

3

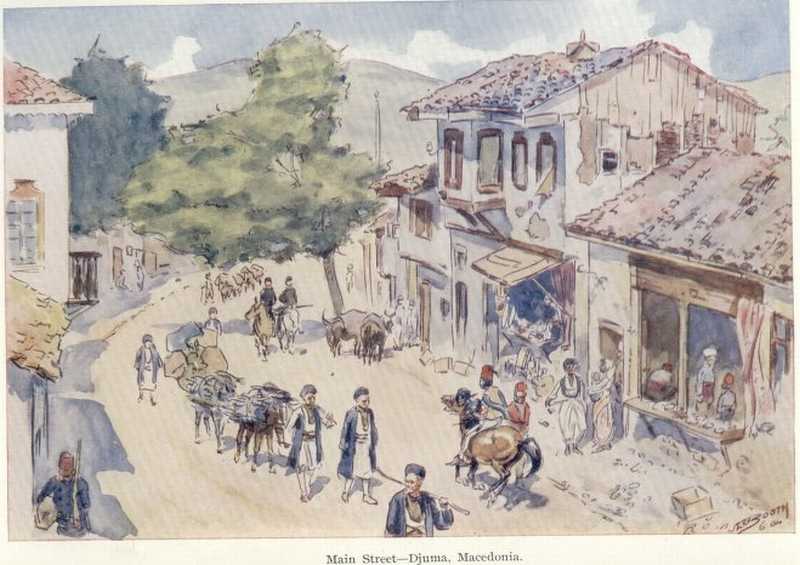

A sing-song at sea.

![]()

4

a solid wind that blew one's moustache into all sorts of shapes, and smelling the good North Sea outside Queenborough harbour.

The caps and noses of the Dutch skipper and officer of the watch peered over the bridge-rail - a sort of wooden wainscoting over five feet high. I wondered whether they picked their officers to fit the bridge, or built this garden paling to the officers' measurements. A small man would have had to bore a hole through it if he took an interest in anything but the sky.

In the saloon was a jovial wight, a Yorkshireman, going back to hunt a pack of hounds for a Hungarian count. He was at once christened "Bill," and responding to the toast of his health sang "We'll all go a-hunting to-day " to "Skip's" banjo, with a lusty chorus of half-a-dozen passengers and the Dutch steward. This worthy producing a fiddle, the concert was soon at its height, and long before the engine-room telegraph rang Slow, "Bill" was standing on the velvet cushions, inarticulate with laughter, reeling off a yarn about "yon lads oop at Middleham Moor."

We piled ashore and were struck dumb in the station corridor by the sight of a lady in fancy dress. Stiff white cap over her pretty fair face, low neck and bare arms, pale blue dress and white apron. She was the lavatory attendant and demanded twopence in a severe voice, instead of singing something about the Zuyder Zee. Romance is dead. In the refreshment room "Bill" was plunging a portmanteau into the backs of the

![]()

5

diners, and cheerily hurling rich Yorkshire oaths at the troubled waiters. No one understood him, and we got him on board the train for Vienna, where he scared away all intruders, and we soon had the compartment to ourselves. But his was a restless spirit, and after he had perambulated the entire length of the train, we found him at midnight in the corridor helping a stout German maiden to knit socks.

Rising ravenous at five the next morning we discovered that the iniquitous refreshment car was not open till ten. Foraging had to be done by rushes in the four-minute stops at the stations, to the great perturbation of the railway folk, who followed our headlong flights waving arms and flags, with shouts of "einstagen, einstagen!" till we were chased into the train.

The German station officials (they use thousands) wear striking clothes of a very military cut - some of them swords. The best people of all have scarlet peaks to their caps. We used to invite the more haughty of them to chip in at our "singsongs," but after eyeing the banjo with some curiosity they retired with a polite bow and a look of pained surprise. To avoid trouble about duty on firearms at the Customs-houses on the way, each of us carried his pistol on him, hidden away under his coat, putting them in the rack between frontiers. "Skip," for greater concealment, wore his Colt under his nether garments on the hip, where it stuck out like a tent-pole under canvas. Fondly imagining it invisible he strode back and forth

![]()

6

among the apprehensive passengers, who eyed the protuberance in some alarm. Crossing the German-Austrian border, I was navigating the corridor as the train swung and rocked over the points, my coat falling gracefully over a bulky Army Webley, when a sudden heave sent me backwards into a stout body. I turned and faced a Customs officer, and for five seconds we looked at each other. The knobby cylinder must have caught him hard; but the dear man's face widened into a knowing grin as he turned and gazed dreamily out of the window. "Bill's" great - coat (it transpired), padded with cigars, had been "thoomped " by a Customs man as it hung from the rack without its contents being suspected, to the ever-recurring joy of the owner.

That night about half-past nine we made Vienna, and the worthy sportsman left us for Pesth to rejoin his pack. They breed a good stamp of horse in these parts, and the pairs that race about in the little victorias, smart and well-groomed, can give points to Paris and Berlin both in looks and pace. They are harnessed with metal rods for shafts, which are fastened to the collars, and have nothing on their backs, which gives them a very light and speedy look.

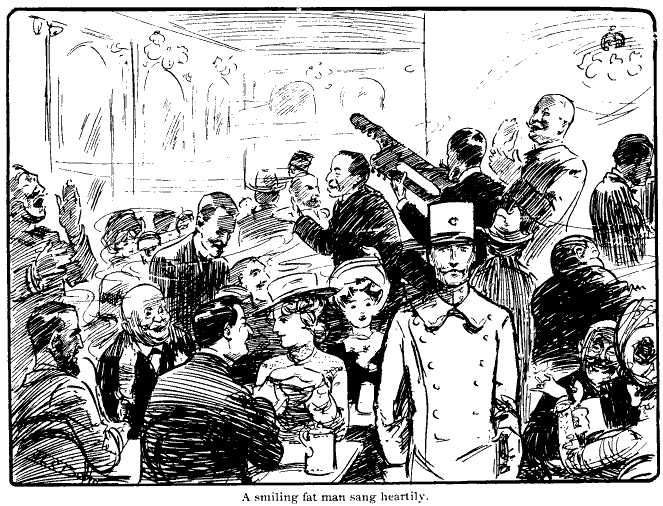

Vienna was enjoying life that night. The wide streets were brilliant with lights and a lighthearted crowd, and every third house seemed to be a café with music going. After dinner we turned in to one of these merry haunts, and smoked pipes and drank Pilsener, while an orchestra of

![]()

7

three or four able men played and sang roystering German songs. Now and then a familiar American tune came on, but some bright native had fitted words to "My gal's a high-born lady" that could be understanded of the people, and, having understood, they shouted the chorus lustily, clapping their hands to the time with an up-and-down motion, as a man beats cymbals. Everyone laughed and was merry, and when one of the singers turned out an impromptu verse about our noble selves and I bowed acknowledgment to the applauding "house," we were welcomed as brothers and holloaed away with the best of them. One of the players was armed with a sort of doubleshafted guitar, which seemed to have the bass notes on one branch and the treble on the other. Attempting to play this ambiguous implement I found very like skating with one foot and walking with the other. "Skip" made something ridiculously like a chord with it, but some men seem born to handle anything from an organ to an occarina. My own instrument is the barrel-organ.

The most troublesome thing in Austria is the money. The gülden and krönen I mastered, but the kreutzers and hellers - well, we talked most about the last ones. The principal currency is copper, about the size of a shirt-button-I forget how many hundred of them make a penny. To avoid giving away too many, the best plan is to ladle out the chicken-food, as Skip called them, three or four at a time, and more in answer to demands.

In the space of a short stay of thirty-six hours

![]()

8

the best thing I discovered in Vienna was the coffee, which is beyond dreams. It is most cunningly concocted, and they serve it in a thick porcelain cup with a great dollop of whipped cream on the top. One is tempted to prolong breakfast till lunchtime, and then drink coffee for lunch. Next to the coffee come the public buildings. These people certainly have some taste in architecture, and if I had spent a fortnight there instead of a day I might be able to write something about it. As it is, all that remains with me is a general impression of size, grandeur, and beauty of workmanship.

Our time was taken up with finding out news, bothering consuls (who, being fixtures, could not escape) and buying railway tickets; for Sofia is such a God-forsaken spot that Cook's in London will not book you there. The Bulgarian Consul, I think, was expecting some people who must have resembled us, and who were liable to wreak him grievous bodily harm. We did our best to look as unconnected with atrocities as possible, and at last won a smile from him. As for news, the papers had little enough of any sort, but the general consensus was for war at once, and plenty of it.

We sought out some genial spirits at the Anglo-American Club, whose hearts were filled with envy at our prospects, and in their mouths the most comforting assurances of the devil's own doings to come. These led us into the bowels of the earth where music raged through

![]()

9

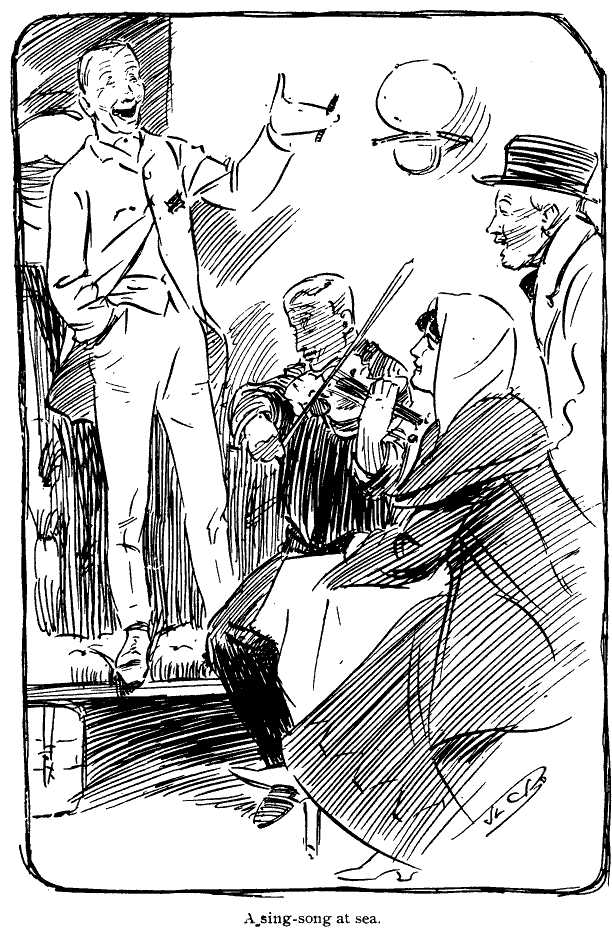

A smiling fat man sand heartily

![]()

10

tobacco smoke from two string bands, and people sat in masses round stein-dotted tables. A smiling fat man sang heartily whilst slim-waisted officers and bulky civilians shouldered their way about. Brilliant uniforms and cloaks crossed and mingled as Austrians, Hungarians, Bosnians, Cavalry and Infantry, with clean-cut faces under their stiff round shakoes, swarmed down into the press. As before, all the singing was done by men, but some gaily-coloured ladies scattered among the tables occasionally joined in. Great was the uproar.

Later, in the strong wave of a chorus, we sought the air again, and visited halls of beauty, where entrancing maidens danced and sang for us. It was a great night for the sketch-book. Later yet, in the wee sma' hours, there was a "union of the English" in the old school songs, and by the time "Auld Lang Syne" was lifting the roof off, with all hands on the stools and the proprietor in tears, our jovial hosts were ready to sell their souls to go down to Bulgaria, and we ours to have them with us.

We walked through the echoing streets to the hotel in the sharp air of an October dawn. Over the dark piles of silent houses the great tower of St. Stefan's Cathedral pointed up - deep violet - into the pale, tender lemon and turquoise of the new day.

The hotel people were all about, and as bright and unconcerned as if it were mid-day. I wonder if anyone ever goes to sleep in Vienna. My

![]()

11

Wolseley bedding-roll seemed to immensely tickle the hall-porter, who rolled it over and punched it with deep chuckles, observing its behaviour under this treatment with the wrapt eye of a connoisseur, and affirming that he had never, never seen anything like it before. I suppose hall-porters are specialists in these things - baggage-fanciers, one might call them - and a new type of luggage excites them in the same way that a new breed of dog would interest a kennel man, or a new star an astrologer. He sighed as he hove the old brown bundle on the carriage, and I feel sure that, had his modest salary allowed it, he would have bought the curio at any price and treasured it as the gem of his collection.

The Staatsbahn Station looked grim and unfriendly at that early hour, so we sat on the steps smoking and observing life till the train was due. A market cart stood outside a little café opposite. The horse had a cold and sneezed till he shook his loose bridle, which had no throatlash, over one ear. A farmer came out of the café and climbed on the cart, shouting to start the horse, which never moved. The man shouted again, pulling a whip from under a rough cloth, and as the horse still stood fast he got a couple of good welts and some more language. At this he merely shook his head, and the man, mumbling to himself, got down and came to the horse's head. The blinker was over the animal's near eye, and he knew the bridle, hanging by one ear, would slip off and get between his legs as soon as he started. The

![]()

12

man grinned, pulled the bridle into its place, and, punching his steed affectionately in the ribs, mounted and drove off. There is the Austrian a horse-lover, who understands his animal. In almost any other Continental country that driver would have seized reins and whip and belaboured the horse till he went on and the inevitable happened.

This railway company is very careful of the safety of its passengers, and to prevent them straying about the system and getting killed they are herded into a waiting room, and kept standing on each other's toes for twenty minutes before the train comes in. This one was full when it arrived, and away went visions of a snooze in the corner seat. I sat wedged stiffly between two fat citizens and looked out on a flat, hedgeless country of mealie-patches and thin trees. At Pesth was a stream of well-horsed turn-outs going to the races, but I did not see a single motor-car. Perhaps the Hungarians still have that sense of the appropriate which we have lost, and use only horses to take them to their race-meetings and meets of hounds.

As a further example of the parental care for its passengers aforementioned, the railway company has caused to be exhibited in each compartment a brief legend in raised metal letters warning the unwary traveller of the danger of leaning out of the window. This kind thought is expressed in four so-called languages, but has not been done in either English or American. Naturally we each felt slighted at this gross omission, and Skip, as a mark of disapproval, hung half his body out of the

![]()

13

window whenever he saw an official in the corridor. From observation of the other occupants of the train we found that such was the fear of death or mutilation inspired by this notice that the terrible windows were kept fast shut, the heroic passengers being then ready to face suffocation with an easy conscience. Under this system of tender solicitation it is also impossible for the most helpless voyager to get lost. The chances of his travelling in the wrong train are reduced to nil, for every hour or so, be it day or night, a watchful and loving person with a brass badge and a punch will consent to look at his ticket - even ask for it and make sure that he is going in the right direction. If the train slowed down a little in the middle of the open country this kind man was round within five minutes in case anyone had scrambled on board.

About half-past nine that night we pulled up at Belgrad, which has a very ordinary-looking station, with no suggestion about it of mediaeval luxuries in the wray of King-and-Queen-slaying. From here onwards there was an insatiable thirst for passports on the part of fierce, bearded importancies, and the growl of "Passapore" in our sleeping ears became a protracted nightmare. Each sleeping-bunk turned up on a hinge in the wall, and like the chest of drawers in the story

"Contrived a double debt to pay -I rigged and climbed to my second-floor dwelling,

A bed by night, a sofa-back by day."'

![]()

14

but for a long while sleep wooed me not. Apart from the passport fiends, a nasal Schlummerlied from my neighbour in the flat below asserted itself too strongly. There is a quality in the Servian snore, whether it be attributable to the timbre or the dynamics I know not, that compels, if not admiration, at least attention. The performance was a masterpiece of execution. Opening with a well-marked largo theme in the bass, a cross-motive of sniffles and snorts was presently introduced. A resonant bridge-passage connected this with a whistling solo for the right nostril. The original theme was now returned to in allegro con brio, and a finely worked up crescendo culminated in a grand fortissimo grunt. I must confess that the " motive introduced" for the last named was a bulky pocket-book, which descended on the snortophone and brought the oratorio to an abrupt conclusion.

Next morning we were charged two francs for going to sleep, and forty centimes for making up our own bunks. To my great glee the Servian Sonata also had to pay - through the nose - for sleeping on the ordinary seat. After breakfast in the cold early morning at Zaribrod, the Bulgarian frontier, a flat sandy-coloured landscape rolled past, open for a couple of miles from the line, then rising to hills, rocky and bare. Between the small scattered bushes and patches of cultivated land grazed straggling sheep, black or white, and flocks of turkeys in charge of little red-sashed girls; here and there

![]()

15

we passed a detachment of troops beating up the dust of a white road. Presently a soldier boarded the train, and we were able to get an idea of the men we had come to see. I sketched him as he stood in the corridor. A flat, blue-peaked cap set back on a bullety, close-cropped head, thick, low eyebrows, and sharp dark eyes, very serious - suspicious of ill. A spare brown face, short moustache and square chin. A young man - not more than twenty-five - but his face was deeply lined. Crows' feet spread from his eye-corners, and he bore what is common to nearly all these men, a heavy line from nostril to mouth corner, and another parallel behind that. A loose reddish-drab tunic, without buttons, fastened up one side, black belt, and loose trousers tucked into wrinkly boots. Short, sturdy, and a stayer. As I finished my sketch the train slowed down, passengers jostled in the corridor and we ran into an unassuming station.

From mouth to mouth ran the word "Sofia."

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]