199

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XIII.

To go and find out and be damned

(Dear boys!)

THE long odds were landed!

How we slogged through that corn and down into the valley, with the perspiration streaming off our faces, to see our driver tooling away through the dust, presenting a large and discreet carriagehood to the unsuspecting escort. Presently a kindly hill shut out the road, and at the first hamlet we picked up a guide for a place we were not going to, and turned him back after half-an-hour's tramp, waiting till he was out of sight to strike our own line by the map and the sun. If the pursuers asked that guide any questions, so much the better for us.

The driver some miles up the road would come to the military post at Strätchin, where he would stop to feed his horses, and the escort would close with him and hear his story. A couple of hours was the most we could count on before the hue and cry started.

The great point now was to avoid human beings of any kind. Walking knee-high through a river - to Sandy's great disgust - we skirted some huts,

![]()

199

crossed a road after careful scouting, and started up a dry watercourse, happily leading in the right direction. This soon grew into a narrow valley with high rocks on either side. In this capital hiding-place we lunched off the hard-boiled eggs, after which I buried the shells - peasants don't eat hard-boiled eggs in the open - at which Alexander tried to cover his giggles, and my base trail-mate laughed openly.

It was a day of dodging roads and skirting villages, of scrambling up perpendicular mountain-sides, and peering for Turkish patrols on the red road below. In the afternoon we struck a mountain trail, and followed it along the range, winding out round each shoulder and down into the woody valleys. Now and again we sighted the little town of Karatova, and a thin note of distant bugles came up from its white tents. Plunging through the bush, a thorn caught my trousers and ripped away a foot of flannel above the knee, which made walking a great deal cooler. At nightfall we dropped down a ragged hillside to a snug little village, and sprawled on the balcony of the schoolhouse with a jar of water whilst the village folk came and had a look at us. The schoolmaster, a Servian, arrived by-and-by with the key, and gave food and shelter in exchange for our confidences and a medjidieh. [Silver coin worth about three shillings.]

His extra room was full of feather beds, piled on the floor, which we were careful not to approach within hopping distance. The pedagogue said he

![]()

200

had plenty of pupils, and looked as if they worried him. He spotted our Palanka bread, so we told him the story. A goat was milked for supper, and I swathed myself in a blanket whilst Mrs. Squeers sat on the feather-beds and mended my trousers. Visitors rolled in and out, and an inquisitive Turk or two; the village seemed to be a mixed community. Naturally they took us for insurgents, and it was quite on the cards that some sporting Moslem might cut off to Karatova, half-an-hour away, and rouse out a cheery gang of wild Anatolian Redifs, whose habit in such matters is to set fire to the house and stand by to shoot anyone who comes out.

I bunked down on the balcony, watching the fire-flies and listening for the "fire-brigade." There was a tree on the hillside where the track came out that got more and more like a man every time I caught it with a dozing eye. . . .

We woke at dawn to find that the rather unpleasant house-warming had not come off, and an hour afterwards were scrambling up a shocking shaley path - the guide, after the custom of the country, walking behind and being shown the way. He was sixty years old and looked a hundred, with the spring of a boy in his short legs. Not a hill did we see on which he had not fought a bloody battle, and slain his tens and twenties. Even twelve months ago the old rascal had been out "over there" - to the southward - sniping the sons of the Prophet from behind a stone, as befits a wise veteran. He had some grounds for his

![]()

201

obstreperous conduct, as he seemed to have been beaten regularly since he was twelve years old.

On a grey level path we swung along through tlle cool beech-forest of Karatova, away above the town, till about ten the huts of Lesnovo village showed scattered across two sides of the valley below. We kicked a way through a couple of dozen deafening curs to the old monastery, and sat down by a stone fountain in the courtyard. The quaint old white structure, brown-timbered, rose on three sides, and over the wall on the fourth stretched the sunny valley. Out came the old abbot, and three or four fat and greasy young monks with hair down their backs, who led up the creaking outside-staircase to a low room. In twenty seconds boots were off and we were full stretch on the comfortable divans. The greasy ones produced food and a jug of good wine, after which we unsociably went to sleep for an hour.

Waking, we found a mute audience of monks and villagers staring from the other side of the room. Here were three refugees, who, with many others, had been driven away the year before by ill-treatment and fear of death. They had lately been compelled to return by the Bulgarians of the Principality, so they said, who had given them five francs each at the frontier. Two had been provided with horses by the Kaimakam of Palanka (all credit to him) to enable them to get to their homes. In this case these had not been destroyed, but all their effects lad been carried off by the troops. This evidence shows that the pea-

![]()

202

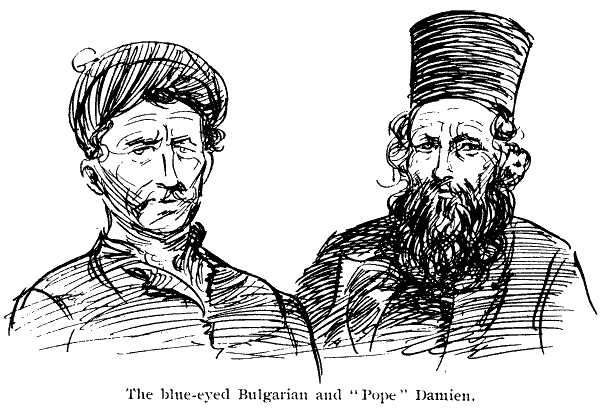

sants speak the truth, because they knew that we were friendly to them, and could easily have suppressed the details about the horses or lied about the houses if they had wished. Another man there, with a pair of good blue eyes, had been tied by the hands to a tree and beaten senseless with staves and rifle-butts.

"I met a soldier," he said," on my way up here, one of those who beat me and put me in prison. He stopped and looked me up and down. He said, 'You are soon recovered, heh? It is time we were round to see you again.' Oh, they are clever, the Turks, but they will not catch me so easily next time. Many of my neighbours were beaten over a year ago and cannot move about yet. Yes, and the women too, they were beaten. One of them died and three gave birth to their children too soon. Well, it is a part of our lives, and how are we to avoid it? One cannot always be going away."

Even the Abbot, Father Damien, could not "avoid it," and was thrashed and hurled into prison for sheltering pilgrims whom the Turks swore were insurgents. He had not long been released, and his arms showed the marks of the blows, and his face the trace of a long cut. It can only be a hereditary hardiness to this treatment that keeps them alive, for it has also been "a part of the lives" of their ancestors for generations. It is no easy thing to be a Christian in Macedonia, and surely the Faith can have no light hold on them when they will suffer thus for it. It makes one

![]()

203

wonder how many of our comfortable church-folk at home would come through the same test. And I have seen these people referred to in certain London newspapers as " so-called Christians "-by fat editors in their armchairs.

The blue-eyed Bulgarian and "Pope" Damien.

Moro rashly promised to take a photograph of the covey of young monks, which had the effect of sending them into hysterics. They rushed off to get their Sunday clothes, but the villain at the last moment discovered that he was short of films and put his finger over the lens. However, they thought they were taken and were abundantly happy, so I don't suppose it mattered.

Outside the village some villainous-looking Asiatic soldiers - some of them niggers - were collecting firewood. They were the bodyguard of the tax-

![]()

204

collector, who went in fear of his life, and small wonder; for if half the stories about him were true he was a big rogue, even for a Turk. Tax-gathering in Turkey opens the road to a grand and almost limitless system of robbery, every move of which this worthy seemed to have at his finger-ends. His escort were too intent on cutting sticks to notice us, and we strode away up a decent path, for once, which led over a big hill to the town of Sletovo. A delightful town to look at from behind a big bush at the top of the hill, picturescquely surrounded by tents, with even barracks to add a charm. The first sight of us from one of those tents by any intelligent soldier and our next move would be to the rear. By great luck a trail led off to the right, which seemed to skirt the tents entirely, and away we went down it, concealed by a shoulder of the hill.

At the bottom the trail turned straight into the town.

There was another path somewhere leading away to the right, but how could we get to it? Just as we had decided on a dash through a corn-patch we came on the connecting-link, a dry watercourse, and were soon on the "circular tour." But now, while keenly watching the tents on the left, an ancient, ruined tower appeared on the right front. Outside this, with his rifle leaning against the wall, squatted a sentry dirging away at the top of his voice some melancholy Turkish song. He was not more than two hundred yards off, and had a good view of the top half of us, but there was nothing to do but go ahead. I believe

![]()

For five minutes our fate hung in the balance. [To face page 204.]

![]()

205

I watched that songster with one eye and the town on the opposite side with the other. For five minutes our fate hung in the balance. Our hats were unmistakable - no one but a European wears anything with a brim on it in Turkey. Once his dull eye was caught by our headgear we were booked. But the amiable creature sang on, his mind far away in his home in Anatolia, till we dropped out of sight to the next stream and took a big drink.

To the faithful interpreter all this was the reverse of entertaining, and his features, when he came up with us, said plainly that any fun we might see in it was hidden from him. We cheered his drooping spirit with "a few well-chosen words," but after wading through a river uncomfortably near the town (the trail fetched a circle right round it) the henchman was reported missing. He was unearthed, some way back, in some long grass, where he said at first he was taking his shoes and socks off, but afterwards confessed some Turks working in a field had shouted at him, on which he had dropped in his tracks and "remained steady." For a mile or so the trail ran through tobacco patches where the Turkish peasants and their women were hoeing and ploughing, but though they showed some curiosity they were not enlightened.

Late that afternoon a few drops of rain came down - a delightful sensation to the parched and dusty foot-sloggers - but presently this increased to sheets of water driven before a cold wind,

![]()

206

and for half-an-hour we clung, soaked, to the slimy face of a bank with little mud waterfalls dribbling into our boots.

In the thick of it came an old Bulgarian, balancing himself carefully on the slippery track, and leading a pony. As he came opposite to us the pony saw a tuft of grass and ducked his head to it, giving the leading-rope a sharp tug. The old man clutched at the air, his feet worked rapidly under him for six frantic strokes, and he fell flat on his back. Unfeeling laughter cheered him from the bank.

When the storm blew over, the path, awkward at any time, was like a switch-back skating rink, down which we slid and staggered with horrible swoops and marvellous recoveries to a boiling yellow torrent below, about as fordable as the Mersey in flood. We christened it the Orange River, with an adjective to express disgust, and scrambled off to find a resting-place for the night and get our sodden clothes dried. A jumble of straw-thatched, mud-walled huts on a hillside was as welcome a sight as a Hôtel d'Angleterre with table d'hôte and hot baths. A mile further on was an even more attractive-looking place, but a minaret stood high above its roofs, and we knew we could not venture there.

The Tchorbaji, [Lit. "Soup-maker."] or headman, of the Bulgarian village received us with the handshake of friendship, and would give us all he had. Sitting on a wooden platform under the low thatch we pulled off our

![]()

207

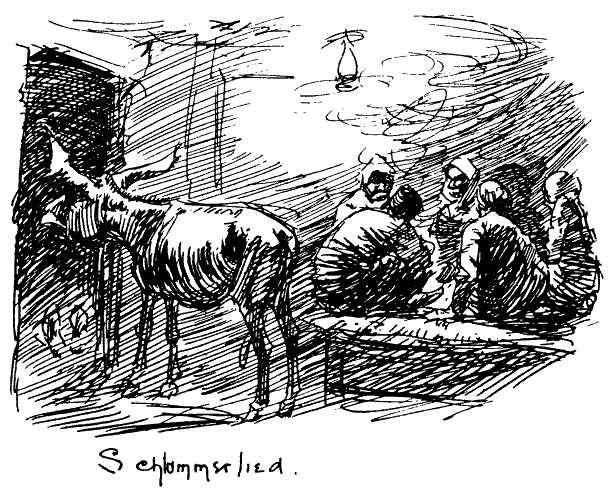

wringing duds to the last stitch, the village - male and female - looking on, absorbed and unabashed. Clad in my "other" shirt, which was fortunately dry, and the lower half of Moro's pyjamas, I scrambled through the henhouse-stable to an opening where, through a wall of smoke, I could make out a fire burning. The Tchorbaji's wooden sandals, built for a lesser foot than mine, were against progress.

With smarting eyes I groped through the smoke towards the "window," a two-foot square hole in the wall on the floor-level, and having tumbled over a three-legged stool, sat on it, feet stretched out towards the wood fire in the middle of the hard earth floor. Using one smoke to keep out another I lit a pipe, and by degrees made out the hostess hanging up our garments to dry. Moro crawled in, and we sat coughing and blinking at the native bread-making. A flat round earthen dish, about two feet across, was made red-hot on the fire, then taken off and the dough slapped into it. Then they buried a lid in the embers, and when hot enough, put it on the top of the dough. This prehistoric oven turns out a fine crust, but the middle of the loaf is very pasty.

Sandy now appeared with an armful of wet things, and hung the hats on a bundle of clothes by the fire, which presently squealed and was discovered to be the latest member of a family fast approaching a score in number.

When the row had died down, we gathered that our "room" had been prepared. This gilded

![]()

208

chamber consisted of the usual mud-floor and walls, with a straw mat and home-made rugs to sleep on. Round a couple of red bolsters were disposed the contents of our pockets in small heaps, and at one end were piled all the family belongings, rolls of mats, old cases, and even a broken box with "Refined Sugar" on it in English. A blessed sight after weeks of lettering that means nothing to you. Here we sprawled and fed under the interested eyes of a donkey and a huddle of torch-lit natives squatting outside; then rolled over and slept like hogs in a barn.

The sun was blazing again when we took the trail

![]()

209

at six o'clock, leaving the old man rather anxious about his safety in case the authorities got to know that he had harboured the fugitives. By this time, as we afterwards heard, cavalry patrols were out scouring the country for us in all directions, and did actually ill-treat one of the unfortunate villagers in whose hut we had slept, though whether it was this one was not plain.

The Orange River had simmered down to a babbling brook when we crossed it and boldly took the main road for Kotchana, a few miles further on. A main road here is no more than a stony path just wide enough for a country cart. Bare, burnt hills rose on both sides, un-decorated by vegetation. In the valley a mealie-patch or two represented agriculture. Behind some brick-heaps a bend of the road suddenly showed Kotchana and its unpleasant military surroundings, so another deviation was called for, straight across country through standing corn. An old wizened man sat under two saplings guarding three little plants in a box. He pointed over his shoulder and we filed along a bank, between the irrigation cuts of wet rice-fields.

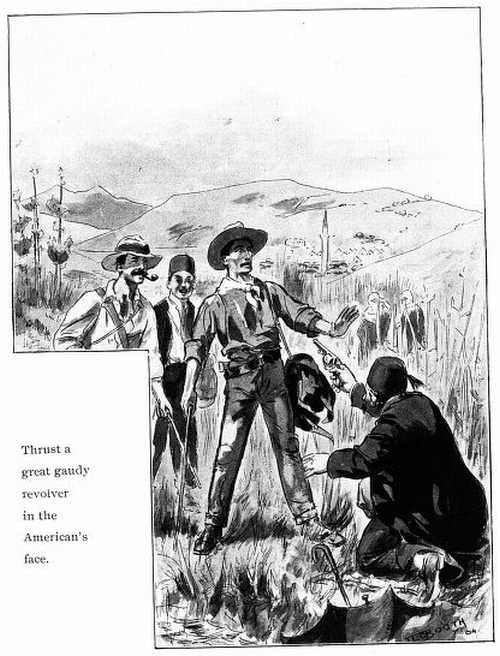

On a dry patch some Turkish women were working, white yashmaks flung back from their faces. At sight of the Giaours the veils were quickly drawn over bent heads, and Moro, watching this, stumbled on the lord of the harem curled up under an umbrella on the bank, snoring. Into the ear of the sleeping husband-man he bawled the name of the village ahead. The umbrella flew into

![]()

210

the "cut" as the stout body lurched on to its knees, and thrust a great gaudy revolver into the American's face. Luckily he did not "pull his gun" in return or the subsequent row would have raised the country against us; and whatever our aspirations, fighting our way through Turkey was not one of them. Moro held out his hand, gently chiding the stranger for his brusqueness, whilst the face behind the firearm gurgled "Teskari."

Sandy to the rescue! Prompt for once, he explained that these were Ingiliz milords, whose contempt for teskaris was only equalled by their pleasure at meeting the Turkish gentleman, and the fiery farmer pocketted his eighteenth century weapon and pointed the way.

The minarets of Vinitza village looked over a clump of trees in the distance, where the foot-hills rose to another range. Three hours later the main road again, and - of all wonders - a passable bridge of black-stained wood. The grass banks of the stream below narrowed where the cool water deepened to two feet on a sandy bottom, and in we plunged. The water seemed to soak into the dried-up skin and put out the fire of thirst the sun kindles in them that tramp under him.

In the midst of our splashings Sandy, who was doing sentry on the road, ran down in a great state of excitement with the news that a cavalry patrol was coming up at a gallop. Springing on to the bank we grabbed our clothes and belongings and ducked under a low wall. They pulled up on the bridge, and as we crouched against the stones

![]()

Thrust a great gaudy revolver in the American's face. [To face

page 210.]

![]()

211

we could hear the officer barking at the men. For the two or three minutes they stopped there we moved ne'er a muscle, and hardly breathed. I remember that my elbow was on a sharp piece of stone, and I wondered why I had been such a fool as to put it there. At last they clumped over the planks and galloped off in a cloud of dust, the officer in a white hood looking to right and left.

Another strained five minutes over.

From their direction and the pace they were travelling we judged that they had been started by the nervous old gentleman with the pistol. Anyhow main roads were evidently bad places to travel on, so we took to the fields again to avoid the energetic horsemen on their return journey.

All the morning Alexander's left shoe had been occupying his mind. Whenever an important point of direction was being settled, and the two travellers' heads were bent over the particular sixteenth of an inch on the map, the subject of this shoe and its failings was introduced in a disillusioned voice. Earlier on I had mended it with a stone, but now the owner declared that it was again ailing, and that it was not enough of a shoe to carry a Christian. We did what we could, but he lagged behind and finally was no more seen.

Within half a mile of Vinitza Moro harked back and ran him to ground in the middle of a barley field. His mind was made up. He would not go a step further; the Turks might take him and drive the spirit from his body. All Bulgarians were martyrs and he was firmly resolved to die.

![]()

212

It was all very well for us, he groaned. If we were killed our parents would receive much money, but what would the Turkish Government give his poor mother?

Already a few stray Turks were gathering round and asking questions.

It was high time to clear away from the neiglbourhood of the village, but

for a long time neither threats nor pleadings were of any avail. We promised

him a horse from the next Bulgarian hamlet if he would only get on his

legs and hobble as far, and Moro took his pack. Having got a chill the

night before I was not going very strong. At last we got him going and

pushed through a belt of poplars on to a dusty track, rejoiced to see some

Bulgarians with a string of pack-ponies going our way. Our cripple was

no sooner astride of one of these than the shoes and the martyrdom were

forgotten. He cocked his fez and joked with his race-brothers like

a clown on a donkey. The next Christian village was "tout près"

- just over the hill - so the wayfarers said; and we slung our oddments

on one of the saddles and trudged on in the dust beside the pack-train.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]