100

PART I. BULGARIA, 1903.

CHAPTER VII.

The trail and the packhorse again,

Salue!

SURE enough we were too late. No more teams could enter Tom Tiddler's Ground to carry on the Great Game. The gates were shut and the janitor could not be squared. So the chèta would none of us.

The opinions uttered in the next ten minutes shall remain unwritten. After that, when the cooling-off process was working, a few ideas as to our own destination dropped one by one into the sulphurous silence, to be taken up and chewed meditatively.

Down in the café corners o' nights there was a whisper among the Mysterious Men of a new rendezvous away over the hills to the south-east. In a valley (low be it spoken) called Tchepina, some of the men of the Samakov district were rallying, and it was rumoured (Sh!) that there was a hole in the boundary fence.

It seemed good enough. Anyhow, whether it came off or not, we were both town-sick - clean fed up with cafés and cobbles - and the trail-hunger was strong upon us. We "desired the hills."

![]()

100

Koyo was called to solemn indaba and the route wrung from him between suppressed bursts of protest. Horses? The hill trail? Without a guide? Not to be done. It was a "mauvais Balkan," infested with people of uncertain manners. To be lost, robbed and starved to death were the least evils that could befall a stranger there. He was quelled and ordered to produce ponies at once. The only things in the town were balanced on two legs each and their ribs rattled audibly. They were left to die in peace, and the innkeeper's own old road-barrow was drawn reverently from its shrine for our use. In this we could get to the railway at Bania, train to Bellovo, get ponies there and ride over the "mauvais Balkan" to Tchepina.

That night we bid farewell to the Gunners. One of them looking in at bedtime found us in a very neglected costume. Skip, never at a loss, caught up a counterpane and flinging it toga-fashion round his manly form, advanced imperially to wag the embarrassed officer by the hand.

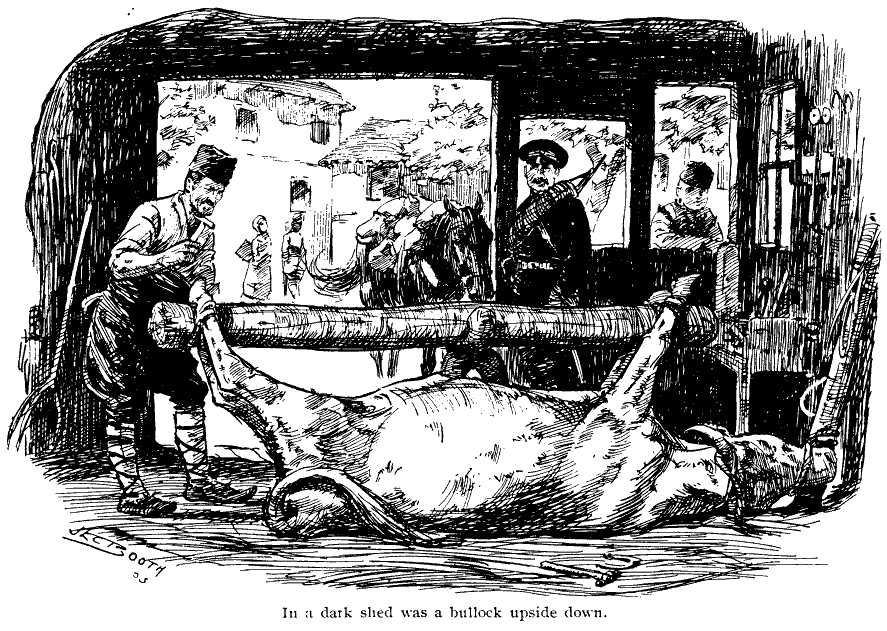

Next morning we took the road, diving gladly into the dust of it, that smelt so different to the dust of the town. Tramping up a hill, a four-horsed fiacre passed, with a Russian Red-Cross nurse going to Burghas to help the relief committee. Taking an "easy" at a half-way village we roamed in the breathless heat towards the clinking of a blacksmith's hammer. In a dark shed was a bullock upside down on the ground, his hoofs lashed to a stout pole held over him by a wooden tripod. The blacksmith was shoeing him with flat discs

![]()

101

In a dark shed was a bullock upside down.

![]()

102

with a little hole in the middle to let the dust in. Some of them hung on the wooden wall among the weapons of the Bulgarian blacksmith's craft, the sight of which would have whitened the hair of his late colleague of the "spreading chestnut-tree."

"Up the hills and down again" till the little lonely station building threw its cool shadow over our sweating ponies. The train whistled in the cutting and civilization came back in a rush.

From the corridor windows the little strip of white, sun-baked road we had just come down was a well-remembered way in a past life. The well-dressed people in the stuffy carriages - going through from the capitals to Constantinople - stared hard, so that our eyes were opened, and we beheld ourselves as dusty tramps, collarless and unpopular. The attendant was hoping for luck in the afternoon when the train got into Turkey. Two days before he had seen the dining-car rise in the air before him over a few pounds of dynamite, just past the frontier at Mustapha Pasha. He wished the Company were in better favour with "ces messieurs" - sweeping his hand towards the hills.

In an hour we were at Bellovo, a handful of red roofs in a mass of timber. Piled planks surrounded it, huge logs cumbered its station yard, and a hillside forest backed it. The sawmill boasted London-made machinery and produced, among other things, a smart little person from "Philippopole" - the name suited him exactly - who kindly translated our needs to the man who owned the local "horses." By the light of recent experience the

![]()

103

animals themselves provoked a deep distrust in the mind from their apparent soundness and very moderate prominence of rib, but after an hour's bargaining (for who will not cheat the stranger?) they were finally booked. We spent most of the afternoon sitting in the middle of the Maritza river under a nice little waterfall, which unwonted sight froze the marrow in the bones of Philip Popole, speechless on the bank.

Next day was Sunday and a brilliant morning. The steeds, promised at six, had to be personally sought at seven-thirty. They were thatched with large wool mats, over which towered a structure of bent ironwork. One of these, in turn, was covered with a small pink pillow and the other with a skin - presumably that of a defunct cow. These, said the owner with pride, were European saddles, procured at great cost and trouble for our special benefit. A pair of very short stirrups, hung far back, helped to concentrate the mind on trivial details for the first mile or so, after which the impression of sitting on the roof of a dog-kennel carried by a calf which one steered with a piece of string began to wear off.

By that time, jogging down the valley road, we had made a little Swiss-looking village, where pigs and babies fought for a place in the stream running down the middle of the street. From here a track shot suddenly upward into the hills at an angle of forty-five, between red-berried bramble-bushes overrun by wild vine. A hundred yards up we had to pull out for a string of wood-cutters' ponies picking their way down with fifteen-foot planks lashed to

![]()

104

their saddles, balancing-fore-end in the air, back end just clear of the ground behind.

Another mile, stumbling up the bottom of a dry watercourse, and the oaks gave way to beeches. The cutting narrowed till the crumbly banks were at arm's length on each side, the leaves closed in overhead, and for ten minutes we tramped in welcome shade, leading the ponies. Coming out on to the ledge-like track again, the hillside across the deep valley showed a great mass of burnt-sienna oaks with a splash of blue-green pine or red-gold birch.

"Hello" says Skip suddenly, "here's a hard-lookin' lot." Half-a-dozen wayfarers sprawling in the scrub stared curiously. Black-browed and unshaven, some of them toyed with young carving-knives and their bulging red sashes suggested a whole armoury of lethal weapons. As we passed one of them flung us the greeting of the road "Dobré." A few hundred yards up, scooped out of the bank, was a small water-hole lined with dead leaves. Unthinking, I let the white pony bury his muzzle in it and suck up the water.

"Better be careful," says Skip, "that's probably a men's drinking-place."

As I pulled the pony's nose out and turned up hill again our swarthy friends with the cutlery appeared, coming up at a great pace and shouting. They had evidently seen the defiling of their waterhole and were bristling with rage. It is useless to try and tell excited men whose language you don't know that you are sorry you have made a bad

![]()

105

mistake, so we mounted and rode on, apparently sublimely indifferent to the yelling behind. Presently the wheeze of their heavy breathing sounded between gruff shouts as they laboured up the steep path close behind; but there is nothing like the timely sight of a wee bit weapon to bring peace to the angry man. The heat was enough excuse for gently pulling off a jacket and revealing, without turning round, a little old brown pistol-holster looking down its long nose. The pursuit melted.

Near the crest the hillside fell away red-carpeted under the huge beeches, the low-toned pre-Raphaelite greens of fern and nettle mysterious in the half-light of the forest. At the hilltop on the south side we sat on the grass, and silently looked down across a wide blue-grey country of little rolling hills, plains, and tiny rivers, away to the faint peaks of the Turkish Rhodope range, hazy under the sun.

To all who have known the Glamour of the Trail, greeting! Tlhe fascination of unguessed country, the pleasure of passing, and the strong delight of unfolding it. The mightiness of the holy hills and the old untouched world. The vast space that makes you realise, and the far-away sea-roar in the pines.

Or the grip of the mere moving along, with the sun smiting on the dry tan in the fork of your bridlehand. The smell of hot horse and the spread of his forelock tossing at the flies. The blue shadow of your boot gliding over the white dust under you, and the little Four-legs of the wilderness scurrying under the rocks and scrub for cover.

![]()

106

Of these, and the stretch-out in the moonlight and the thousand spells of the open, is the Glamour of the Trail. It enfolds you and gets into your blood, and lays the germs of go-fever to torment you at awkward times in civilised places.

I know of a man, deputy-assistant-sub-manager at a big London railway terminus, whose nerves went wrong, and he was sent to Switzerland by his doctor. In a fortnight he was back again, bored to death by those great dull mountains and longing for nothing but the friendly smell of the trains and the clatter of his familiar station. To each his own!

Buried in the forest on the crest were two or three woodcutters' huts, where the leather-skinned axemen lived with their families. In the clearing a couple of Mounted Police and three men afoot with rifles and bandoliers were arguing furiously. As we watched, the insurgents broke away and spread for the frontier at top speed, with the mounted men after them. With their active ponies the Police soon rounded up the runners, and, pistol in hand, drove them back down our old trail. Here was the prohibition law in actual force. The woodcutters looked on grinning.

We rode up and queried, "Tchepina?" The old hunter of the camp, with his ancient single-barrel gun slung on his back, guided the wanderers over the thick pine-sheddings and out to the ledge of the hill. With a fire of detailed directions (our Bulgarian stopped short at six food-names and a swear-word) the good-natured savage waved us

![]()

107

farewell, and, bridle over arm, we zigzagged and staggered under the noses of the slithering ponies down five hundred feet of toboggan shute.

At the bottom was a trickle of water, which at full strength had worked a deserted sawmill. Here we lay down and drank deep, and thereafter, worrying brown bread and cirenje, recalled a long-ago morning in the Orange Free State when we two, thirsting for

![]()

108

the blood of Christian de Wet, had solemnly divided a "Marie" biscuit for breakfast.

Then, mounting the pink pillow and the cowskin, on again across a strip of burnt grass, over a hump or two, and then another long down-grade. Here, in rock and bush, the meagre trail lost itself, and so did the riders.

After half-an-hour's plunging in impenetrable bush we discovered an old shepherd and shouted to him, pointing down the hill. He shook his head in acquiescence, and getting into a dry stream-bed the ponies picked their way down into the valley. Thumping over a cranky wooden bridge, a straggling hill-village showed up. At the doors of its uneven, switchback street loafed a few sour-looking ruffians in fez and narrow turbans. These were the Pomaks - Bulgarian-Mohammedans. Their ancestors probably accepted the religion of the Prophet as an alternative to instant death, but the modern Pomak follows Islam more fanatically than the Turks themselves.

In a wooden shelter like a square bandstand - always built over a stream - we rested awhile and watched the folk come to the fountain. It was shaped like a section of a wall, with two spouts and a stone trough in front. One man brought a tray filled with grapes, which he held under the spout. I watched him with a good deal of interest, for I had often eaten those wet grapes and wondered where and in what manner the washing was done.

A tiny maiden with two clay pitchers balanced on the edge of the trough waited for him to give

![]()

Down five hundred feet of toboggan shute. [To face page 108.]

![]()

109

space. On her close-plaited fair hair she wore a little red fez with a couple of small charms in front, a little ragged Zouave jacket over a white chemise, and a faded striped apron wound round her for a petticoat. She filled her pitchers, then dived with her hands in the trough and swallowed three or four grapes swept from the washer's tray.

Two women walked gracefully to the fountain. One had a loose white jacket made with a hood to cover the face, except the eyes; the other wore the yashmak, a soft veil wound about her head. Most of the Pomak women have the Turkish custom of veiling, and seeing those who go uncovered one can only wish the veil were universal.

Beyond the village the trail crossed their strange neglected old cemetery, each grey head-stone shaped like a bed-post with a turban on it. Now we were in the Tchepina valley, on a flat track which touched the coils of a snaky river for the last four miles. Fording a couple of hot streams - their sandy bottom streaked with grey sediment - we pulled up at last by the little rest-house in Lojena village - eight hours from start to finish, and thirty miles as the snipe flies.

Lojena squats in the middle of eight small villages called the Tchepina district, and is chiefly little darksome drinking-houses. Perched at one end is a bit of a barrack where a few lonely infantrymen look after the road to the frontier.

In the soft, short twilight some familiar drab jackets and white legs appeared mysteriously like bats, flitting about between the doorways. After

![]()

110

pummelling the crusty overseer of the stable till he produced food and water for the ponies, Skip and I wandered out down the dim street, with the notion of finding some of these fighting men and pushing a claim to membership of their brotherhood.

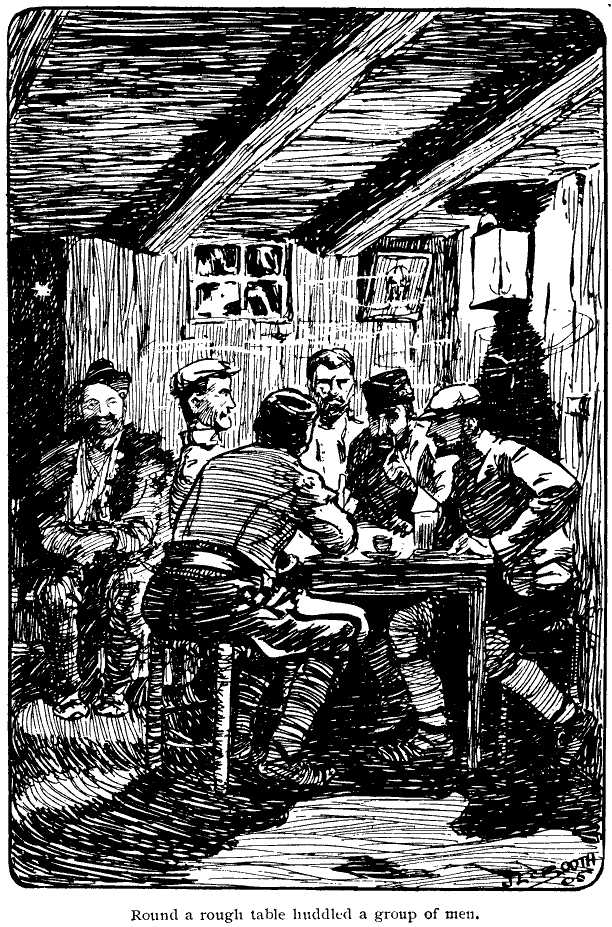

A square of lamplight in a low doorway looked inviting, and we peered in. A few feet below, round a rough table, huddled a group of men, heads together over their coffee cups. A low note of talk came up through the cigarette smoke. They broke off and stared at the intruders, who sat apart with a glass of vino; then the sluices were drawn again and the streams of rhetoric flowed on.

Of course the sketch-book came out, and one by one the models drifted over and gurgled at their pencil faces. Down the steps into the half underground den lurched a wild-looking object with ragged skins over his shoulders. He was hailed with shouts of "Ancho!" and shoved on to a bench to sit for his portrait. With the shy smile of a débutante and eyes on the floor the embarrassed "looney" suffered the ordeal, the other men crowding over the book and chuckling with merriment. Their drab-clad leader, turning the pages, found a Turk's head. "Ah! " he snapped, and the laughter dropped dead as he fired a harsh question.

"Sofia, Sofia," said the accused artist, and things grew easy again. Strangers from Turkey are not welcome among the "clans."

We all talked volubly in the sign-language, and my partner's imitation of shooting Turks was entirely convincing. I often think of those con-

![]()

111

Round a rough table huddled a group of men.

![]()

112

versations and all we told each other, and then remember, marvelling, that not six words could have been spoken.

It was plain that they had been trying to get through into Macedonia, but without success. The application of a little vino conjured up brighter hopes for the future, and the possibility of two of the Foreign Legion joining them in another dash for liberty and what-d'-you-call-it. We parted firm friends and went to bed.

At the horrid hour of midnight a light flashed in my face and dark figures filled the room. Someone apologised in French for the intrusion of the police. Out of a dark corner came the drowsy Boston voice: "This is where little Willie goes to gaol." I saw the pair of us transported to Sofia loaded with chains - legs tied under the ponies - to be tried for high treason or lèse majesté, or some such peccadillo. The imposing parade only wanted to see the passports of their casual visitors, and thumped out again with their lanterns.

At breakfast their spokesman, a stout doctor, came to renew his apologies, and was himself decoyed into the conspiracy, so that before the morning was out he was in close confab with the ringleader in the underground drinking den, egged on by the foreign fellas. But the bandsmen had thought better of it in the night, and little old Bulgaria was good enough for them.

"Too late-too late for this year." Besides, the Turks' peasant-shooting season had closed.

"In the spring-yes, if the Englishmen come

![]()

113

back in the spring we will take them with pleasure."

We climbed back into the air again - dead failures.

"Huh! Bet your life! . . . . 'There'll be trouble in the Balkans in the spring,'" quoted Skip ironically. "Where's their grit? Don't amount to a hill o' beans."

The doctor was emphatic on the hopelessness of any further attempt, and there was nothing for it but the home trail.

At half-past four the next morning we sat in the dark eating bread and cheese and swallowing tchai (thin tea and sliced lemon in a glass), waiting for the dawn. Not till six was there light enough to see the trail. The hot streams were steaming in the cold dusk as we cantered down the valley with a sporting peasant on a smart bay pony. Away over the Sunday trail, till up in the hills we halted to watch the sun rise through rolling pink clouds over the mountains of Macedonia.

Neither yearned to ascend the toboggan shute - "nema, nema!" Cunningly we chose a way leading by gentle stages round the obstruction, forgetting the base treachery of mountain trails. The pestilent path tacked uphill and lured us further from our point at each leg of it. Then, having landed its victims in the thick of a young pine forest and four inches of snow, it vanished without a word. Towing the ponies, we made a bee-line through those crowded Christmas-trees to the crest. The bushes grew close together like turnips and shot

![]()

114

avalanches of snow down the necks of our open shirts. Under the wet snow on the ground were invisible logs, and every ten yards one of us was flat on his face with a grunting pony on top of him.

"By - the ten - colours," growled Skip between his clenched teeth, pulling his old hat out of a drift and welting his jibbing animal from behind, "whoever made you - made a mistake."

Sodden from head to heel and sweating in the sun, we struck the cross-track on the summit and jogged along the top of the divide to pick up our down-trail at the woodcutter's camp. Some eagles circled in the air over the carcase of a sheep, and waiting till one settled on a dead tree I stalked him with the Webley - and missed.

* * * *

At half-past five in the evening we steamed into Sofia station in the rain. Empty, sloppy streets; empty, smelly hotel. No news, and everything gone flat as a punctured air-balloon. The town was dead, and all our "gang" gone home.

We packed our kits and followed them.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]