9. A Rogue Hound 162

11. Still Shirking 208

15. Back Home 306

BACK TO THE HUNT

THERE is an expression in American slang, which is eloquently descriptive of personal satisfaction. As the Centurion stepped out of his araba and entered the Pera Palace Hotel on the following morning, he "felt good," as this expression has it. Barring a truculent censor and the Act of God, there was nothing between him and the realisation of the object of all his efforts. The Marmora Express lands its passengers at Galata full early in the morning. The Centurion was able, therefore, to disappear into the privacy of his room without going under the cynosure of all and sundry of the guests at the hotel. As everybody who has stayed in this institution knows, the hall porter is the personification of discretion. The Centurion had only to suggest to this functionary that he

![]()

154

was still to be considered as being at the front with the Turkish army, and he knew that his presence would not be disclosed.

How a message was sent to the Centurion's colleague in the capital, and how this colleague loyally placed himself at his disposal throughout the day, is not part of this narrative. It will suffice to say that all arrangements for the despatch of the messages were satisfactorily accomplished, a supply of petrol puchased and placed upon a special launch that was hired to take the Centurion back to Rodosto that evening.

It was considered expedient that the Centurion should not appear openly in the capital, as it was just possible, in the circumstances, that the General Staff might not appreciate the fact that there was direct information from the armies in the field already arrived in Pera. Constantinople itself was in a fever of excitement. Although the General Staff had issued daily bulletins to the effect that Mahmud Muktear Pasha was having big and continued

![]()

155

successes on the Viza front; that the Fourth and Second Corps were holding their own manfully at Lule Burgas, yet there was other and more truthful information circulating, which told of disasters in the field and hinted at the general retirement which had already taken place.

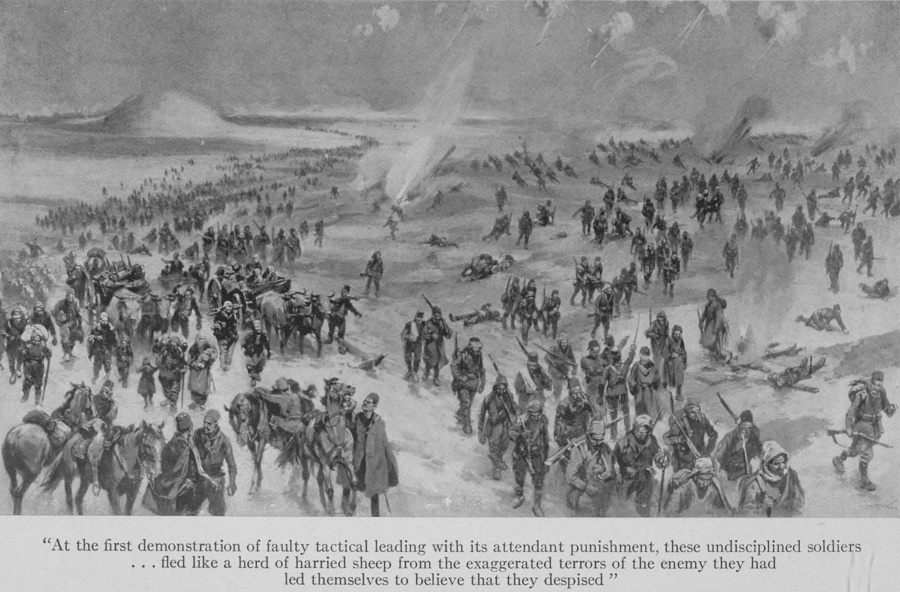

Pera is the home of rumours and even distances Shanghai in the amazing quality of its falsehoods. It was generally believed that morning, in European circles, that the Turkish Army, utterly routed and actively pursued, was stampeding for Tchataldja. Colour was given to this exaggerated statement of the situation at the front, first by the wish of Levantine circles that was father to the thought, and secondly by the clever fabrications which the Bulgarian General Staff permitted to pass as news to a privileged paper in Vienna.

From this latter source, the whole of the press of Europe was inspired with a continual story of Bulgarian heroism. In spite of the

![]()

156

fact that the Bulgarian successes were admirable enough in the naked narrative of truth, the world was informed of magnificent exploits by independent cavalry; of terrific carnage at the point of glistening bayonets; of tactical successes, Napoleonic in their conception and Japanese in their realisation. Before these word pictures, a truthful narrative was a tepid and unworthy lucubration.

The Bulgarian General Staff had doubtless entered the province of the news agency business with a definite object. With admirable secrecy they had veiled the conduct of their campaign in its earlier stages. They did not at this moment wish Europe to know that their much vaunted system of supply and transport had developed unexpected limitations. It was not to their advantage that Europe should realise the poignant truth of the casual remark which it will be remembered the Centurion had made to the Diplomat: "Both sides must take a breather soon." While the British Ambassador, upon information received from

![]()

157

the British legation at Sofia, was telling his colleagues that the Bulgarian independent cavalry had appeared athwart the line of retreat of the Turkish armies and had turned that retreat into a hopeless rout; while the privileged Vienna newspaper was telling Europe of the Turkish Sedan which had made the dry bed of the Tchorlu River run red with Ottoman blood, the Bulgarian armies, faint and exhausted, were resting on their arms, counting their losses and thanking the Christian's God that something had intervened to make the Turks evacuate the positions which they themselves were too exhausted to face again.

The launch which the Centurion hired to take him and his petrol back to Rodosto, was timed to leave the Galata wharf at seven in the evening. It was a stout little harbour tug of about sixty tons, and it was considered capable of doing the voyage to Rodosto in six or seven hours. Although the vessel flew the British flag, it was captained and manned by Greek and Italian Levantines. When the Centurion

![]()

158

went on board, he found that neither the skipper nor crew could speak a word of English or French. In ordinary circumstances this should not have mattered. There had, however, been an angry sunset, and it looked very much as if the tug might chance into dirty weather. These Levantine sailors are particularly weatherwise, and as the tug cast off its moorings, the sailors in a neighbouring boat gave them a peculiar send-off, which was ominous in its friendly sarcasm.

The elements of fortune enter into our daily lives in some inconceivable manner. Without worrying about the psychology of the law of chances, it is certain that there is some rule which intervenes to mend or mar all enterprise designed by human artifice. During the earlier portion of this campaign, there was a vein of misfortune that put a certain drag upon the carefully laid plans in the Centurion's campaign. To begin with, he had started the adventure weighted down with a transient malady that might well have confined

![]()

159

him to his bed. Once free of this malady, he was faced with the shortage of petrol on the arrival of his car. Again, on the culminating day of the battle of Lule Burgas, his henchman had failed to arrive at the tryst with his horses, and now he was to be faced with another set-back in the spin of the wheel of fortune. This is not set down as a peevish endeavour to explain away any element of failure. It is only mentioned to show how one adventurer may have to struggle against the many elements of adverse chance, while another will have the good fortune to find success through channels totally unforeseen.

The launch had not been an hour at sea when she struck one of those furious local gales, for which the Marmora is famous. Of the malady from which the Centurion suffered, stowed away in a narrow fo'c'sle bunk, there is no necessity to speak. The passing personal inconvenience of mal-de-mer is nothing in the scheme of things. What that storm meant, however, was that much of the Centurion's

![]()

160

energy and despatch was wasted, since the rain that fell in sheets would render the road impassable for his car between Rodosto and Tchorlu. The writer will not dwell upon the hideous sufferings in that fo'c'sle, but at one period towards midnight, the situation became so desperate that the skipper, dripping wet, made his way down to the Centurion, and shaking his head with gloomy energy, pointed suggestively to his feet. Being unable to converse with him, except in the most primitive Italian, the Centurion realised, between the paroxysms of his malady, that the captain suggested that any attempt to continue the voyage was courting destruction. On personal grounds, the Centurion was in such a state of collapse that he felt that the sinking of the craft would have been a happy release, but he had his duty to consider, and so he murmured "Courage" and turned over on his side, leaving the captain to work out the salvation of his boat as best he could. Three times between midnight and morning the skipper

![]()

161

came down to try and induce the Centurion to agree to a return passage to Constantinople, maintaining that in the last three hours the boat had not made more than a knot. With daylight, however, the tempest somewhat abated and by ten in the morning the tug was almost rolling her boilers loose in the open Rodosto roadstead.

![]()

162

A ROGUE HOUND

THE Centurion's worst fears were realised.

The hills behind Rodosto were clouded in dim mists and it was pouring rain. It was evident that it must be days before the car would be able to negotiate the road to Tchorlu. There were, too, further disappointments in store. After the usual difficulties of landing, the Centurion made his way to the house of the British Vice Consul, to learn, as he had feared, that on the previous day his most dangerous rivals had reached Rodosto in the Panhard. What was worse, the Austrian Lloyd that should have run to time, came in the same afternoon that they arrived. They had boarded her and were now safely in Constantinople in time to catch the Constanza communication. This meant that although they had missed Saturday's paper, yet they would

![]()

163

run equal with the Centurion and the Diplomat in the long and uncensored messages that would appear in the Monday's papers. Of such is the fortune of war.

The Centurion learned that, if that particular Austrian Lloyd boat had not run twenty-four hours late, there would not have been another boat to take the adventurers to Constantinople for at least three days. Three days in the life of war news is a very big affair. The disappointment was natural. The Centurion could not but feel at the same time some satisfaction that his close friends and colleagues had not been put in the humiliating position of having to wait days to get their messages away. They were both dear fellows and had undergone the same strenuous difficulties as himself. The Vice Consul said that the two had passed a nerve-shaking day in Rodosto. They of course knew that the Centurion was away with the news, and it was uncertain, owing to the existing state of war and its attendant difficulties at the Dardanelles,

![]()

164

whether the Austrian Lloyd boat would put into Rodosto at all. As the afternoon drew on and there seemed to be little chance that the boat would arrive, both the Dumpling and his companion had fallen into the depths of dejection. Then suddenly the packet appeared round the point and they were transported to the seventh Heaven of delight. Only a journalist can appreciate their feelings at this moment.

The Centurion tried to glean some information from the Vice Consul of what had happened at the front since he himself had left. The latter, however, knew nothing and said that both his visitors of the previous day had discreetly maintained an absolute silence concerning the happenings in which they had participated. There was, however, considerable evidence in the town that much disintegration had taken place in the Ottoman armies of the left wing. Rodosto had filled up in an extraordinary manner with deserters from the army. A large percentage of these were of

![]()

165

the Christian element, which since the revolution the Turks had admitted to military service. The craven attitude of many of these was deplorable. They were without money or food and were begging from door to door, not only for bread, but for civilian clothing, that they might shed their uniforms and thus disappear from the military ken.

Rodosto is full of Geeks and Armenians. This particular type is not over-scrupulous in its methods of making money. Brand new Mausers were purchasable for five piastres, while handfuls of ammunition were thrown gratis into the bargain. The Armenians who engaged in this traffic in arms defended their action in these transactions by claiming that they feared every moment the Turks would let the canaille of the town loose upon them; they, therefore, had no compunction in buying Turkish arms in order to defend their homes and families from the final vengeance of the Crescent. This, of course, in the majority of cases, was all eyewash. The Armenians were

![]()

166

not content with this one traffic; they carried their nefarious transactions into another field. They were battening on the misfortunes of the thousands of Turkish refugees dumped down upon them. They purchased for a song the live stock of these poor wretches. In spite of their nomadic traditions, the refugees were now suffering awful experiences. It had rained without intermission since the preceding night. The town being on the slope of a hillside, the streets in places had become rivulets. The mud and filth collected during the recent extraordinary conditions of life was in most places ankle deep. The rain had come in with a piercing cold wind and it was a heartrending sight to see families curled up in the slush, trying to keep their miserable bodies warm by burning the cart wheels which had brought them to the coast. Babies were cradled in slush. Women and children were drenched to the skin. The live stock that was these poor vagrants' sole worldly wealth, was sold for a trifle to the rapacious Armenians in

![]()

167

order that the simplest necessities of life might be forthcoming. Trust an Armenian or a Greek to miss an opportunity! They knew that they had the refugees in the hollow of their hand and they at once made a corner in bread, and no refugee could purchase this simple commodity except at extortionate rates. Is it to be wondered that the simple and slow-thinking Turk has at times risen in his wrath and exterminated in their hundreds these parasites?

It was to unhappy surroundings that the Centurion had returned. The consular corps which consisted of a group of Levantine Vice Consuls, was still obsessed with the belief that the moment the Turks finally evacuated the town, they would leave orders behind them for a general massacre. The wires which were still working to Constantinople, were kept red hot with pathetic appeals in cipher for foreign warships to be sent to save the Christian from the onslaught which was never even meditated. The Centurion did his best to allay the

![]()

168

fears of this cowering section of the European race. He pointed out that there was no certainty that the Turks were in such desperate straits, that they would leave the town without a garrison. The word "massacre," however, has been so seared into the brain of the Christian Levantine, that the conditions of his squalid life have only to be removed a fraction from the normal and he believes himself and his'compatriots to be in imminent danger of a violent death.

Having been interviewed by each of the Levantine representatives of the foreign powers domiciled in Rodosto, and having heartened up each in turn with the promise that they would not be massacred forthwith, the Centurion wandered down to the han to see how matters went with Hamdi and the car.

At the han he found Adolphe, Adolphe is the Dumpling's dragoman. He is altogether a very estimable personage. He calls himself an Austrian and he carries himself with

![]()

169

the dignity of a man of knowledge and account. Adolphe, knowing the close relationship between the Centurion and the Dumpling, was expansive as to the latter's adventures. After he had made the corner in petrol, the Dumpling took the Muradli road and arrived at that station on the Thracian railway just before sundown. As has already been explained, the road from Rodosto to Muradli is the only real provincial road in European Turkey. The Dumpling's chauffeur, who was a young, excitable youth, having gained confidence at the progress he had made on the sound metalled bottom, thought that he could take the heavy Panhard with equal audacity along the country roads. The result was disastrous and the great forty horsepower car stuck hopelessly in the slough. The disaster was so complete that it was impossible to correct anything that night. The car had to be left where it was and, on foot, the Dumpling and his retainers made their way to Muradli Station. Here they were on

![]()

170

the fringe of the operations. Muradli was a point that many hundreds of broken troops from the First Corps touched. The Dumpling found the station commandant hospitable and discursive. Even with his good will it was impossible to move the car that night. It remained where it was and in the morning, with the aid of bullocks, it was at last dragged out of the mudhole. The Dumpling then cut across country to the Tchorlu road to find himself in the midst of the retiring Turkish army. With great difficulty the heavy car was urged on through phalanxes of retreating soldiers, and reached the han at Tchorlu late in the evening. Here the Dumpling found some of the other adventurers, who, during the retirement, had broken away from the Bosniak Shepherd. Here was found Jew's Harp Senior, who after most terrible experiences at the front with Abdullah's headquarters had, by an almost miraculous succession of fortunate events, arrived back at Tchorlu almost in the last state of exhaustion. If he had not been

![]()

171

able, on this particular night, again to join forces with his partner in the Panhard, it is probable that the brilliant description of his desperate experiences would never have reached his paper in time to have realised the success that they deserved. Early the following morning he and the Dumpling fled in the car to Rodosto and by the skin of their teeth, as has been shown, caught the overdue Austrian Lloyd boat. In such circumstances are journalistic triumphs made.

Hamdi was next consulted as to the possibility of the car making the journey to Tchorlu. He shook his head despondently. Hamdi was as anxious to get back to the front as his master. Nature, however, had intervened. As there was no definite information to be found in Rodosto, the Centurion determined to make a reconnoissance to Muradli Station. The metalled road to this point was possible in all weathers. Local reports in the town were definite that Bulgarian troops would be found half a dozen miles outside the

![]()

172

town. Circumstantial evidence was tendered as to the treatment the invaders had extended to the villagers. The Centurion would accept none of this. According to his calculation there was still no reason why the Turks should have fallen back from this point.

The members of the consular body looked upon the reconnoissance as a foolhardy affair, but they were a chicken-hearted body. The road to Muradli was all that was claimed for it. It was ominously deserted and the car just spun along. Within three miles of the Station the car met a great collection of village carts heading for the town. They were in charge of an aged Mulazim in faded uniform, and a round dozen of decrepit mustafiz (last ban reservists). The Centurion learned from the officer that he was clearing the villages of all food stuff that could be of any use to the enemy. He was confident that Ottoman troops were still at Muradli. The Centurion was pleased to find that the Turks could show such workmanlike energy as to clear the country

![]()

173

before the enemy, but this energy foretold a contemplated evacuation.

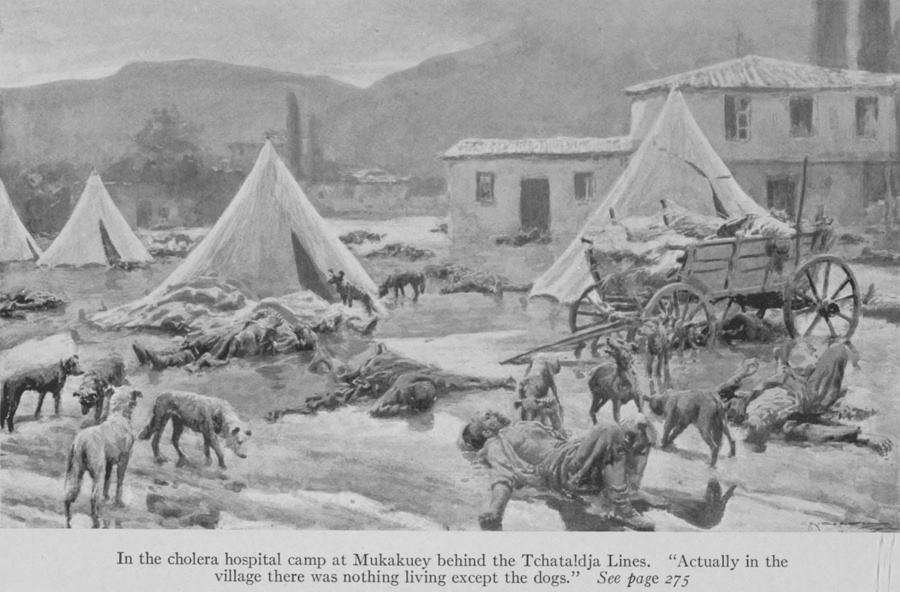

As the car crossed the iron bridge into Muradli village there seemed an absolute lack of life about both the village and the station buildings. There was no rolling stock. The place was deserted. Hamdi took the car right on to the metals, and pulled up in front of the booking office. Save for a tame little brown mongrel, that showed unwonted signs of joy at the arrival of humans, and a flock of astonished geese there was nothing living in the place. The station offices were locked. Except for a few jettisoned pontoons and a half dozen old pattern ammunition wagons the place was cleared of all military stores. Sign of living Turk or Bulgar there was none. The Centurion swept the far horizon of the gently sloping downs with his glasses, and peered long down the parallel of the dead straight, permanent way. Crest line and vanishing point betrayed not the slightest evidence of any living thing.

![]()

174

The Centurion was nonplussed. It was evident that the Turks had retired. It was just as obvious that the Bulgarians had not advanced. The Turks had retired in good order, since they had taken everything with them. The useless material they had jettisoned was neatly parked in the station yard as for inspection. It was impossible that the Bulgarians had pushed on, on the heels of the Turks, without occupying Muradli. Strategically such an omission was unthinkable. The railway was of vital importance to them, for though Adrianople still refused them the main line, yet they had captured two locomotives and rolling stock at Kirk Kilisse. There was only one solution. The Bulgarians at Lule Burgas had, as the Centurion had thought, put their last ounce into the battle and had not been able to advance since. No other reasoning would stand examination.

Although Muradli was not on the direct march route from Lule Burgas to Tchorlu, yet the top of the ridge over which that road

![]()

175

passed was visible from the station. Muradli Station lay two-thirds of the way between Lule Burgas and Tchorlu at the bend of the Ergene River. There was no movement on the ridge. It would have been impossible for an army to pass that way without first occupying Muradli.

"Well," said the Centurion to Hamdi, "if the Bulgarians are not here, they ought to be. Anyway they are likely to come here pretty d—d quick. We had better not stay or we may be nabbed by some inquisitive patrol."

On returning to Rodosto the Centurion found unexpected confirmation of the diagnosis he had made at Muradli. The Vice-Consul reported that he had heard that three more adventurers had arrived at the han from Tchorlu. The Centurion straight away went down and discovered his French colleagues. They had left Tchorlu that morning and ridden down to the coast. They were overjoyed at finding the Centurion, who had already been reported killed.

![]()

176

As soon as they could be induced to talk coherently, the Centurion gathered that they had broken away that morning because the Bosniak Shepherd had ordered the residue of his flock to abandon their stores, and take train immediately for Tcherkeskuey. They said that on the night when the Centurion had last seen them they had had a trying experience. They had bivouacked out on the veldt. On the morrow they had been overtaken by the army in retreat and hustled back to Tchorlu.

Rather than suffer further at the hands of the Turks, the Frenchmen had thrown in their hands and determined to take the first boat to Pera. They said that all the English adventurers had disappeared and that the Germans and Russians alone remained loyal to the Bosniak Shepherd. They dilated on the horrors they had seen; the dangers on the road to Tchorlu; the corpses of refugees dead of cholera and a thousand and one terrors. It was evident that they had contracted the epidemic known as "cold feet." This epidemic was

![]()

177

curiously prevalent at that period in the Turkish Army. It was, however, almost exclusively confined to the ranks of the partially trained troops.

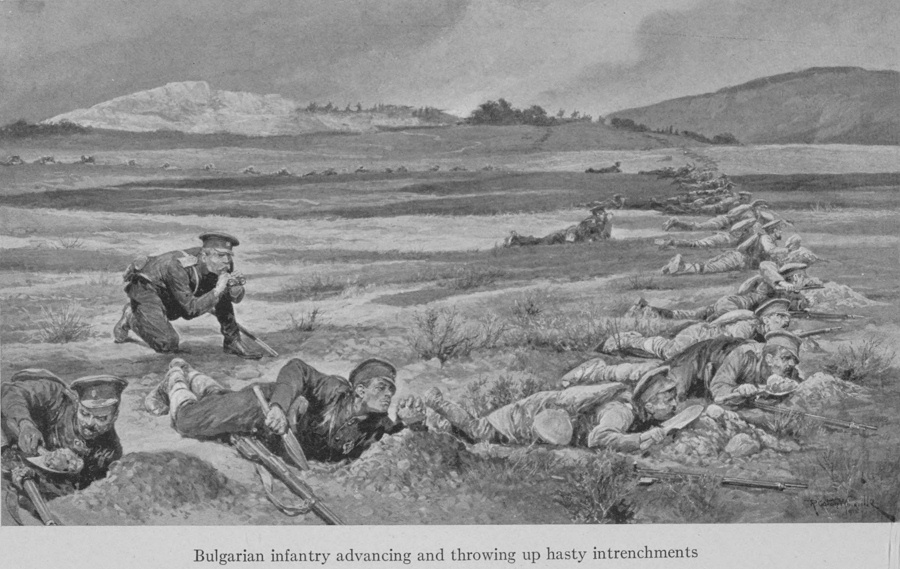

The concrete information that they were able to give the Centurion was encouraging. There was still a very large Turkish force in occupation of Tchorlu and, to the Frenchmen, it looked as if this force intended to stay there as it was busily engaged in throwing up field works on positions covering the town on the north.

On the following morning Hamdi gave a dubious assent to attempt the return journey to Tchorlu. An early start was made. For the first five miles progress was fair. There were evidences on the road, as suggested by the Frenchmen, that some epidemic—or perhaps starvation and exhaustion—had overtaken several of the fugitives. It was curious to find that the rearward movement of fugitives seemed to have stopped. The only troops that were passed on the road were small formed

![]()

178

bodies heading to Tchorlu. After the fifth mile the road passes over a long swampy plateau. Here misfortune overtook the car. Hamdi had feared this plateau. His worst fears were realized. The car sank into a morass; the wheels lost their purchase, and the machine became hopelessly bogged. Hamdi, however, was an energetic fatalist, and he said cheerily, "No good—go fetch cow." There was no village in sight, but he trudged off happily.

There are moments when it is legitimate even for an optimist to give way to despondency. For the next six hours the Centurion sank as deeply into the Slough of Despond as his car had penetrated into the trough of the morass. The wind had veered round to the north again, and blew in bitter draught across the plateau. There was not a living thing in sight. Only the boundless area of the billowy downs. It is hard to imagine a more oppressive solitude. To be absolutely alone with an immobile car in the centre of a great grassy

![]()

179

wilderness in Thrace! The impotence of it all!

From time to time groups of Turkish soldiers sauntered past and gazed upon the incongruous spectacle with lazy indolence. A few of the more curious came and passed the time of day and earned as a remuneration for their welcome curiosity the gift of a cigarette. It was the sense of impotence that crushed the spirit. The Centurion fell to wondering what the Diplomat, his partner in the car, must be thinking and whether he was waiting his return to Tchorlu. Perhaps he also had given him up as lost or dead.

After an absence of two hours, Hamdi loomed up on the horizon with his "cow." He had commandeered a pair of buffaloes and a driver. It would have seemed just if, at this period, the tribulations of the journey had ended. However,"it was not so. The buffaloes were hitched in, and with Hamdi and the driver at their tails, they took the strain. There was a sickening crack, and the yoke

![]()

180

broke into two pieces. With this the cup was full. Even Hamdi ceased to smile.

After a moment's reflection he borrowed a cigarette from the Centurion, and bade him mind the cow-boy and the team while he trudged back the three miles to find another and a stronger yoke. The next two hours the Centurion passed in absolute misery. At last Hamdi returned with a serviceable harness. Opportunely a squad of soldiers arrived simultaneously. With their help, and that of the engines, the buffaloes finally towed the car at a snail's pace through the swamp. The remainder of the journey was tedious going. There was not, however, another serious delay and towards evening the minarets of Tchorlu separated from the winter mists, and the car climbed the last rise into the village. It had taken eight hours to do the twenty-two kilometers.

There was no doubt about the Turks still being in occupation of Tchorlu. The temporary barracks on the Rodosto side of the village

![]()

181

were teeming with soldiers. For the first and only time during the campaign the Centurion was stopped and questioned by an examining post at the entrance to the village. The interrogation was perfunctory. It was remarkable, nevertheless, what inadequate measures for protection had been taken. The Centurion found that Hakki Pasha's division and the headquarters of the Fourth Corps were at Tchorlu. Although an adequate line of outposts had been thrown out to the north of Tchorlu cantonments and railway station, there was nothing protective along the front by which the car had arrived beyond the one examining post. An enterprising Bulgarian squadron leader could have had a lot of fun if he had slipped round by way of the Rodosto road. But there had been little worthy of the name of enterprise on either side in this dully conducted campaign.

It was a pleasure to the Centurion to feel that he was back with Ahmed Abouk's command. He now discovered the Fourth Corps

![]()

182

had not had much to be ashamed of in spite of the brilliant word-painting of those of his colleagues, who had let themselves go on the "retreat from Moscow" racket. It is curious how quickly the accomplished journalist can see red, and how difficult he finds it to draw the line between rout and retirement. Fortunately there were no professional journalists with the Tirah Field Force when it scuttled down the Bara Valley in 1897. If there had been, the historical exactitude of the operation would have been as prostituted as has been the retirement of the Turkish Armies from Lule Burgas. These things are difficult to explain to the lay mind. The proof of the pudding, so runs the time worn adage, lies in the eating. Here was the Centurion at Tchorlu, six days after the general retirement of the Turkish Army was ordered from the line Lule Burgas-Viza. Tchorlu was only thirty-five kilometers—that is one day's march—from the battlefield. At Tchorlu was a Turkish rearguard consisting of the complete infantry division

![]()

183

which had covered the retirement of the left wing of the Turkish armies and between it and the enemy again, was Salih Pasha's independent cavalry division. For five days neither of these divisions had fired a single round. Where then was the rout? Someone or another has lost his sense of proportion. It was the First Corps that was routed, and this was at Yenidje days before the struggle at Lule Burgas.

Tchorlu was simply bristling with troops. It was with difficulty that the car was able to make its way through the streets. The batteries were all lined up in the main thoroughfare. The teams were feeding with their harness on ready to hook in if an emergency should require sudden movement. The Centurion drove direct to the han, hoping that he should find the Diplomat and his own caravan there. The hanji, who recognised him as the truculent adventurer who had destroyed his bedroom furniture and then paid handsomely for it, received him with open arms. Alas! John,

![]()

184

the Caravan, and the last of the foreign adventurers had left the previous day by march route for the south. Somehow the Centurion did not fancy the han, so he went out and tried the empty house in which the Diplomat, the Innocent and the Popinjay had lodged. The caretaker, having reaped a rich harvest from these three, welcomed the Centurion. The latter having shared his last lunch-tongue with Hamdi for the evening repast, was only too glad to turn in.

![]()

185

STILL A ROGUE

IT would be difficult to describe the true state in which the Centurion found the village of Tchorlu in the morning. As the north wind of the previous day had foreshadowed, it had again turned bitterly cold. The town was absolutely packed with Turkish soldiers muffled up to the eyes in their overcoats and bashliks. They looked the picture of misery, but all soldiers look thus when they are campaigning in winter weather. There was, however, no disorder. All the bakers' shops were working at high pressure. There was a guard upon every bakery, and no issue of bread was allowed unless it was through the agency of the particular non-commissioned officer in charge of the supply. The town was picketed throughout and thoroughly patrolled by the gendarmerie. All these duties were of

![]()

186

course carried out in the casual, slovenly manner which is characteristic of Turkish methods.

There was one matter, however, that escaped all surveillance. This was the sanitary control. The state of the Tchorlu streets absolutely beggars description. One has read of the filth that was wont to accumulate in the middle ages in English towns. In the midst of modern conveniences, one shudders to think of what those conditions were. Imagine, therefore, the state of the narrow streets of this Turkish village after thousands of soldiers had passed through and an entire division had been billeted in it for a matter of five or six days. It was simply horrible and in the winter's stillness a kind of pungent reek hung over the whole place. If ever epidemic disease was courted it was in these filthy surroundings.

As soon as Hamdi had refreshed him with a jorum of cocoa, the Centurion made his way to the headquarters of Ahmed Abouk Pasha. On occasions like this the man who observes

![]()

187

the formality of sending in his card to a Turkish dignitary only courts delay. The Centurion walked boldly into the corps commander's room. The dear old fellow, who looked more like a bronzed English farmer than a Turk, showed no resentment. He was obviously surprised to find the Englishman at the front and his first remark was:

"Why are you here? All the foreigners and attaches have been sent away long ago."

The Centurion answered that he had been fortunate enough to lose his way, but he was now glad that he had done so, since it gave him the opportunity of rejoining the best corps in the Turkish Army, and that, anyway, it was his business to see fighting and not to hear about it second hand. The old man's eyes twinkled at this naive confession of faith, as he answered: "You are not going to see any more fighting just yet because the Bulgarians will not come on, and I have orders to retire my division to Tcherkeskuey."

The Marshal then gave a résumé of all that

![]()

188

happened to his corps since the eventful day when the Centurion had been with it in front of Lule Burgas. Much of the information he gave has already been inserted in the preceding narrative. He said that Hakki Pasha's division had remained as rearguard until the whole of the rest of his own Corps and the Second Army Corps had been withdrawn. The Bulgarians, it appears, made one rather feeble essay to force in this rearguard, but they were easily checked, and it had fallen back without opposition to Ciflikkuey and Sandakli and then to Tchorlu without firing a shot. Mahmud Muktear's corps, on the extreme right of the Turkish line, according to Ahmed Abouk's information, had been forced to retire, both from Bunar Hissar and Viza in conformation with the retirement on the left.

Here there had been some effort at pursuit by the Bulgarians and when the right Turkish wing, still conforming to the general retirement, fell back to Sarai, it was still feebly harassed. At Sarai all pursuit had finished

![]()

189

and Mahmud Muktear's army had fallen back leisurely upon the new alignment.

"But why did you retire at all, Excellency?"

The Pasha's face hardened.

"We fell back because it was ordered so by fate. You may tell your friends in England that if the Fourth Army Corps was beaten, it was beaten by ourselves. My men had no food for over fifty hours. The best soldiers in the world cannot fight in these circumstances. What is worse, the supply of ammunition failed. I had to collect every unused round from my other divisions in order that the batteries of Hakki Pasha's rearguard should have sufficient at least to make a pretence of keeping the Bulgarians back. But the enemy were in no better condition than ourselves and if I had only had food I would have driven them back upon the Maritza with the bayonet."

"And the future, Excellency?" asked the Centurion. The Pasha turned up the palms

![]()

190

of his hands in the impressive gesticulation of the East. "It is in the hands of God. It was the first intention of Nazim Pasha that we should hold Tchorlu. Then it was changed to Tcherkeskuey. Now I am ordered to fall back to Tcherkeskuey to cover the army that has been withdrawn right back to Tchataldja."

"And what of the Seventeenth Army Corps, Excellency?"

"As far as I know, there is no Seventeenth Army Corps. We have all believed in it. We have all been told that it was coming to our help. Mahmud Muktear Pasha held on to Bunar Hissar expecting it. Torgad Shevket was driven to make a counter attack in order to give time to it to come up. It has proved a fantasy. The Redif units of which it was to be formed were never properly concentrated and they consisted for the most part of untrained troops. As they came up the magnetism of battle absorbed them in every direction, mostly to the rear."

![]()

191

"What of the First Army Corps, Excellency?" The old man as he answered got up from his seat, thereby indicating that the interview was shortly to be closed. "Don't speak to me of the First Army Corps. It is their half trained intellectuals that lost me the battle of Lule Burgas."

As he shook hands with the Centurion, he added,

"What do you propose to do?"

"With your permission, Excellency, I will stay with you as long as I may."

"We shall be enchanted for you to stay with us as long as you like. Perhaps you would like an escort?"

"There is no need, Excellency, for an escort. With the Turkish Army I am chez-moi." The old man smiled as he said on parting, "You pay us a great compliment; it is true no escort is necessary."

The Centurion went back to his commandeered house to find that he had two unexpected visitors. These were Jamal Bey, a

![]()

192

civilian volunteer, and Ismail Hakki Effendi, a cavalry officer with whom the Centurion had been intimate during the Albanian campaigns. Jamal Bey was a friend from Constantinople who, flushed with patriotic enthusiasm, had volunteered for service. Owing to his capabilities he had been attached to the signalling staff of the unfortunate First Army Corps. Before he left Constantinople, the Centurion had arranged with him for a service of information. During the disastrous retreat of the First Corps, Jamal Bey had contracted a bad attack of dysentery. He had crawled into Tchorlu the evening of the day the Centurion had left for Rodosto.

Herein lay further evidence of the vein of bad luck in the Centurion's calendar. Jamal, in drawing the han for him, had fallen into the net of a rival, who had pumped him dry. The poor fellow was now almost at death's door and the Centurion insisted that he should immediately lie up in the commandeered house until he himself could take him in the car to

![]()

193

some place where adequate medical treatment was available.

Ismail Hakki, however, was in the best of health and spirits as far as a Turkish officer could be in spirits at this period of their unfortunate campaign. He had an independent troop of cavalry attached to the divisional headquarters, and since the battle of Lule Burgas, had been employed by the divisional commander as an officer's patrol. He had come in on the previous evening, and hearing that the Centurion was at the han, had come down to invite him to accompany him that afternoon when he went out with a new patrol. Ismail Hakki, like Ahmed Abouk Pasha, the corps commander, was a Circassian. He was one of the few Turkish officers who had done military training in France. He was a thorough soldier, imbued with the keenest intelligence and a constructive cavalry genius. The Centurion jumped at the offer. He had no horse, but Ismail offered him a troop horse.

As Ismail's patrol rode out of Tchorlu early

![]()

194

in the afternoon, the Centurion felt the fascination of again being a mounted swashbuckler. They had given him the best horse to be found in the troop, a great rakish Hungarian with a mouth of iron and heart of steel. Ismail took only six men with him. He had but fourteen horses fit for duty and he was wise enough to use them in relays. His men were tough looking fellows. Riding in their overcoats with their carbines slung across their shoulders they looked like Cossacks. Ismail's information was that there were Bulgarians at Seidler Station and at Ciflikkuey. Salih Pasha's cavalry division should have been on the line of the Ergene River, somewhere in the vicinity of Karahansankuey. The orders were for the patrol, if possible, to work round to the west of Seidler and discover if there was any movement behind the Bulgarian advance guard. Ismail's orders gave him permission to remain out twenty-four hours, after which he was to report back at Tchorlu to the headquarters of the cavalry division and then

![]()

195

rejoin his own divisional headquarters, which would by then have fallen back in the direction of Tcherkeskuey.

As the horses were sufficiently fresh, the patrol moved rapidly to the Ergene River, passing along the high ground that overlooked Muradli Station. A couple of troopers who were detached for the purpose reported Muradli Station to be in the same deserted condition that it had been two days before When the Centurion visited it. Seeing no evidence of their own cavalry division at the point on the Ergene at which he selected to cross, it was necessary for Ismail to proceed with some caution as he approached Seidler. Crossing the railway line at Inanti, the patrol moved cautiously, parallel to the railway line and river, up towards Seidler village.

The village is some three miles south of the railway station. The scouts who went on ahead reported all clear, and the patrol trotted in amongst the ramshackle houses. At first it seemed as if the village was entirely deserted.

![]()

196

It was marked in the intelligence report as being chiefly occupied by Greeks. This proved to be the case, as at its northern end were found the houses of two or three substantial Greek farmers. These men and their families were all at home. There was also in the place a small posse of mustafiz.

It was now almost dark and Ismail, being wise enough not to bivouac in the village, especially in which there were Greek inhabitants, just remained long enough to drag with the aid of the mustafiz as much information as was possible out of the Greeks. The Greeks were at first a little reluctant to talk. Ismail's treatment of them might perhaps be considered a little rough, but with the aid of the butt ends of the mustafiz' Martinis, he learned that a patrol of Servian cavalry visited the village that morning, that it came from Seidler station and had gone back there. One of the mustafiz also said that a Greek, who had come from the direction of Lule Burgas, passed through Ciflikkuey, and had seen there a number

![]()

197

of mounted men. He had not said whether they were Servians or Bulgarians. The patrol moved out of Seidler, and Ismail with the cunning that he had acquired in France, moved out in the opposite direction to that which he intended to follow to find his bivouac. After he felt he was out of earshot of the village, Ismail changed his direction and moved to the back of a hill that commanded both Seidler village and the station. Here the patrol ran into a shepherd driving home a flock of belated sheep. This man was a Turkish Bulgar. He was immediately seized and, perhaps, a little roughly handled to put him in the necessary obedient frame of mind. He was then instructed to lead the patrol to some place in the vicinity where it could make a convenient bivouac. He was led to understand that if his memory failed, he would cease to be a shepherd pretty d—d quick. After an extremely short march, he led the patrol to an ideal spot. There was an empty

![]()

198

kind of sheep pen and stone penthouse, with a spring quite close, the water from which had not yet frozen sufficiently hard to prevent the horses from watering. As soon as the horses were tied up in the corral, Ismail, the Centurion and his Choush (troop sergeant) climbed to the top of the hill to select a spot for the posting of a night sentry. The night outlook from this point of vantage confirmed the information that had been gleaned in the village. There were a number of fires blazing in the vicinity both of Seidler Station and Cliflikkuey, and further away to the north little twinkling points of light suggested that there were other troops bivouacking above Karisdiran, but these latter were so distant that they might have been only the usual village lights.

Having instructed the Choush where to post the night sentry, Ismail and the Centurion returned to make themselves as comfortable as the cold would permit. Already the troopers had pulled a rafter out of the penthouse and

![]()

199

had a fire blazing under the mask of the south side of the corral. There is something very brotherly in the intercourse between officers and men in the Turkish service. It must also be remembered that amongst Mohammedans all men are equal in the eyes of God. This philosophy leads to an intimate intercourse between all ranks which could hardly be understood by those used to the European methods of enforced discipline.

With the exception of the night sentry, the whole party grouped themselves in a semicircle round the fire and proceeded to participate in the evening meal. This consisted simply of rough bread and water. Ismail himself had nothing better, but the Centurion had three tins of cheap sardines in his haversack. These he at once produced. Turkish politeness forbids, that in like circumstances, gifts should be accepted from a guest. It was only by the most vehement insistence that the Centurion could induce these rough brigandlike looking soldiers to partake of this relish

![]()

200

to their simple meal and to dip morsels of their bread in the oil of the sardines. The Bulgarian shepherd also did not escape attention. As he had produced an adequate bivouac, he was admitted to the fraternity of the camp fire, and was also provided with bread and a sardine from the common stock. The only precaution taken with him was that his right wrist was bound securely to the left wrist of one of the troopers.

It was a bitter cold night. Mercifully there was no wind. Although he was clad in a sheepskin, it was far too bitter for the Centurion to think of sleep. In short, it was an all-night sitting, and the monotony was only broken by the periodical relief of the night sentry. Ismail Hakki opened his heart to the Centurion during the weary watches. He traced most of the evil misfortunes that had overtaken the Turks to the part the army had taken in the revolution. He said that the whole country had gone to pieces because the people did not know to whom to extend their

![]()

201

loyalty. He suggested that if Abdul Hamid had been left at the head of the State this fearful debacle would not have overtaken the Empire. For this line of argument he had two reasons. The first was that the old man was so clever in the fields of diplomacy that he would never have permitted the Balkan Alliance. By some means or other, by the gift of Crete here, or economic concessions elsewhere, he would have detached one or another of the allies. The second was more intimate. The old man had exercised an influence and control over the army which had found no substitute under the new regime. It may be that Ismail himself believed that there was more general pilfering of public funds and jobbery under the Hamidan regime than with the advent of the Constitution, but there was that factor of personal control by the Sultan, which in a moment of emergency welded the army together. Some subtle force in his authority produced results that were beyond the powers of the new General Staff. It did not matter

![]()

202

how these results were effected; if Abdul Hamid's Irade went forth there was an impetus that somehow carried them through. If Abdul Hamid had been in power there would have been no failure of food at Lule Burgas or shortage of ammunition. Ismail Hakki felt the situation keenly. Although not a Turk in the true sense of the word, he had a large share of the traditional amour propre of the nation. From the bottom of his heart he cursed the Young Turks and all their works. Nor was he singular in this feeling. The Centurion, as he extended his circle of acquaintances amongst the Turkish officers, found there were many who thought like his Circassian friend.

Ismail was also inclined to be bitter at the handling of the independent cavalry division. He did not wish to be disloyal to his chief, but realising how the division would be led in the field, he made a personal application that resulted in his detachment from the independent cavalry division to those duties in which

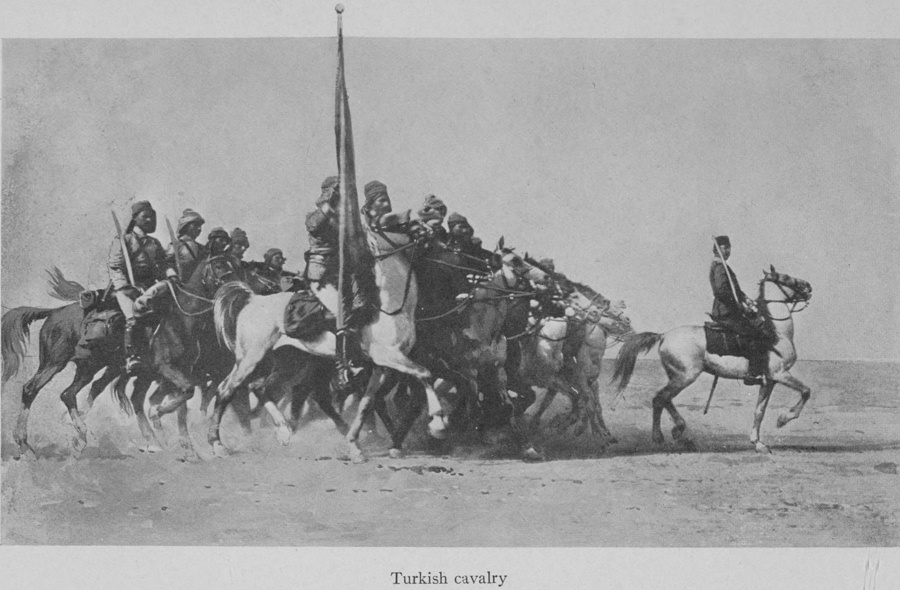

---

Turkish cavalry

![]()

203

the Centurion found him. He traced the indifferent handling of the cavalry to the German instructors. "If you want to know anything about cavalry in Europe," he said, his eyes gleaming in the light of the logs with the fire of the true cavalryman, "you should not go to Germany but to France. Cavalry work is not in our days a matter of weight and masses! It is a question of finesse. No German understands finesse, while every Frenchman is an adept in it. Look what has happened to our cavalry here in this campaign. It has all the time been bundled about from place to place on the pretence that it was looking for an opportunity to charge the enemy. Where do you find an enemy's cavalry? Is it behind your own infantry? What has Salih Pasha done with his fine division? In twenty days of war, he has reduced its effectives by fifty per cent. Does he ever spare his horses? The men rarely dismount during the day and have never off-saddled at night. How has he done protection duties? Has he detached independent

![]()

204

squadrons while he was resting the remainder of his forces? Has he ever practised his men in defending or taking a position dismounted? I know that he has not. It can almost be said that these men do not know how to dismount or to unsling their carbines. He has been content to work his horses to death, up hill and down dale well out of range of any circumstances that could be turned into military utility."

This is a scathing criticism. The Centurion did not know how far Ismail was justified in placing the responsibility with the German instructors. The question is whether these German instructors had had an opportunity of really instructing the Turks. Is it possible to break down the inveterate conceit of the Tartar mind and make it receptive of instruction? Did the German officers set about their duties with enthusiasm, or were they just wasters from the Prussian service attracted by the shimmer of piastres? These are questions which the Centurion was not competent to answer,

![]()

205

but he could endorse every word of the strictures which Ismail passed upon the independent cavalry division that finally marched through the Tchataldja lines and was sent to recuperate at the Sweet Waters. The veterinary hospital at Daud Pasha was a sight warranted to break most cavalrymen's hearts. The Turkish horse soldier, officer and man, knows nothing and cares less about horse mastership. Thus the night was passed. In the last bitter hour before dawn the horses were fed with the last bite of corn remaining in the nosebags. The patrol then set out to glean some definite information with regard to the camp fires they had located the previous evening. Nor had they far to go, since it was soon light enough to make out the surroundings of Seidler Station. It was seen that at least a regiment of cavalry was standing to its horses. At the same moment the nearest outpost that had covered the bivouac, opened fire on the patrol. It was a foolish thing to do, as it gave Ismail time to get away before any of the

![]()

206

enemy were in a position really to interfere with him.

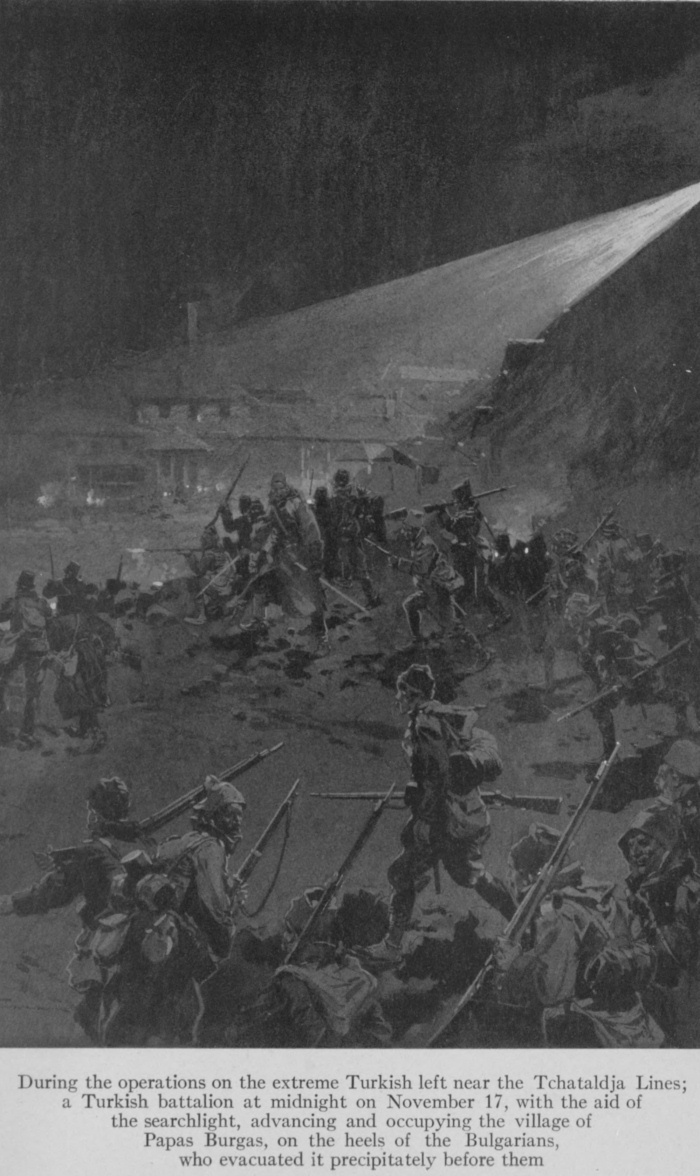

The patrol fell back rapidly due west, then getting into the folds of the downs, climbed up a formidable ridge that overlooked Kajabali. From this point Ismail secured all the information that was necessary. He was in an unapproachable position, as any attempt to turn him or force him out could be seen for a radius of five miles. The panorama gave a sweep of the entire Ciflikkuey-Karisdiran valley. There seemed to be a cavalry regiment moving out of Karisdiran, while on the main Lule Burgas road was bivouacked a force of all arms which, by counting the artillery park, was estimated at the strength of a division.

At last the Bulgarians were making their forward movement. Ismail was quick-witted enough soldier to see that he had accomplished his mission. It was his duty to get back to Tchorlu in the shortest possible time. The patrol returned by much the same route as it had come and was back in Tchorlu village just

![]()

207

after midday. Here a great change had taken place. Hakki Pasha's division with all its impedimenta had disappeared. Its place had been taken by the independent cavalry which at this time was reduced by the wastage of war to about the strength of a single regiment.

![]()

208

STILL SHIRKING

WHEN the Centurion got back to his commandeered house, he found still another surprise in store for him. He found the General in possession. It will be remembered that he and the Diplomat had last seen the General when they were in the car on their way back from the battle of Lule Burgas. The General was delighted to find a pal. He had had a desperate time of it. After they had left him he had caught up Salih Pasha's cavalry division and, being hospitably received, had attached himself to the Pasha and had remained his guest ever since. Once he came back to Tchorlu to get something to eat, since existence with the cavalry had proved almost synonymous with starvation. The General had been back in the village just at the period when the organisation of the latter-

![]()

209

day adventurers had broken up. He was, therefore, able to give the Centurion more definite news than the latter had gleaned from the excited Frenchman. It appeared that all the foreigners had been suddenly ordered to "footsack" from the front. By this time the English section of the Bosniak Shepherd's flock were absolutely desperate, and on receipt of these orders they had vanished to the four winds. He himself, having been made an honorary member of the cavalry division, had no intention of going back to the base, and had slipped off to the front again.

He was able to give the Centurion news of his own caravan and John. It appeared that the General had found John in the han in the last state of despair. He had had one of the Centurion's horses commandeered; he had been captured by the'bibulous Bey and ordered under threat of instant execution on no account to wait longer at Tchorlu and he was without funds or orders. In the circumstances the General came to his rescue and lent him

![]()

210

£15. Thereupon John had collected the caravan and marched south with the retreating army.

As far as the General knew, the majority of the English adventurers had also ridden south. Some had gone to the coast in the direction of Siliviri. It was the General's intention to continue to follow the fortunes of the cavalry division. This the Centurion believes he subsequently did, for he was reported missing for a long time, until it was discovered that he had been taken prisoner by the Bulgarians and spirited away to Kirk Kilisse.

As the Centurion learnt at Tchorlu that the cavalry division's orders were to fall back the moment the Bulgarians showed any sign of advancing in force, and as what he had seen with Ismail's patrol convinced him that this advancing force was less than twenty-four hours distant, he considered that he would be cutting it rather fine if he remained longer in Tchorlu. The choice was open to him of taking the car down the Adrianople road in the track of the

![]()

211

main army, or of returning to Rodosto and shipping the car from that port to Constantinople.

The Centurion argued that if he returned by the Adrianople road, he would be much impeded by the impedimenta on the march and he would also run the risk of falling into the hands of the Bosniak Shepherd at Tcherkeskuey or Tchataldja. Knowing as he did the orders that had been received by the commander of the Fourth Corps, it was obvious that even with the best will in the world and the utmost energy, there could be no fighting at Tchataldja for at least ten days. There might be, however, most interesting developments if the Bulgarians followed the example of the Russians in their campaign and made Rodosto their first point of contact with the Marmora. He, therefore, decided upon the Rodosto road and instructed the now very sick Jamal to be ready to make the journey at daybreak on the following morning. Jamal somewhat demurred because it was stated in

![]()

212

his hospital certificate that he was to proceed to Hademkuey for treatment. The Centurion told him frankly that if he went down by cart to Hademkuey he would be dead in forty-eight hours. He pointed out that his only chance was to come down to Rodosto, where he could get medical attendance, and then take the first ship to Constantinople to be nursed in his own home. One or two friends from the cavalry division who came in to see him in the afternoon, also endorsed this view and prevailed upon him to accept the Centurion's advice.

There was some difficulty in getting the sick man away in the morning early. Besides, the Centurion wanted to satisfy himself that Salih Pasha really intended evacuating Tchorlu. The Pasha was some time making up his mind and finally said that he would not begin his rearward movement until the enemy reached the Karahasankuey ridge.

The Centurion, realising the easy way there was round to the southwest of the village, determined not to chance any untoward development.

![]()

213

He watched the cavalry division bring its solitary battery of horse artillery into position on the high ground near Tchorlu station. Satisfying himself that the demolitions which had been effected were of sufficient extent to delay the enemy, and transferring the sick Jamal from the house to the car, he started on what was to prove an adventurous journey back to Rodosto.

There is one beauty of the Thracian soil as viewed from the standpoint of the motorist. The result of rain soon vanishes, except in the bottom of the valleys. After three days the going on the Rodosto road was moderately good again. The car made the journey at an average speed without adventure until half the distance had been covered. Here at the top of a rather steep rise is the village of Hadzi Muradli. The climb up to this village is severe, but once the ridge is passed a long gentle decline faces the traveller for nearly six miles before he meets the last big ridges which lie between him and the sea.

![]()

214

The car was just beginning to make the ascent up to the village, when, at the bottom of the valley, about three miles away to the right, the Centurion observed five horsemen. There was something suspicious about the attitude of these horsemen. They were halted. With the naked eye it looked as if they were grouped in astonished observation of the car. The Centurion pointed them out to Hamdi, who, throwing the quick eye of the accomplished chauffeur in their direction, murmured the word "Bulgar."

The Centurion turned round and saw that Jamal was half somnolent in the back seat. At the very moment that Hamdi made his diagnosis the horsemen started to gallop at a slanting angle up the ridge. Their direction showed that it was their intention to cut the car off before it reached the summit.

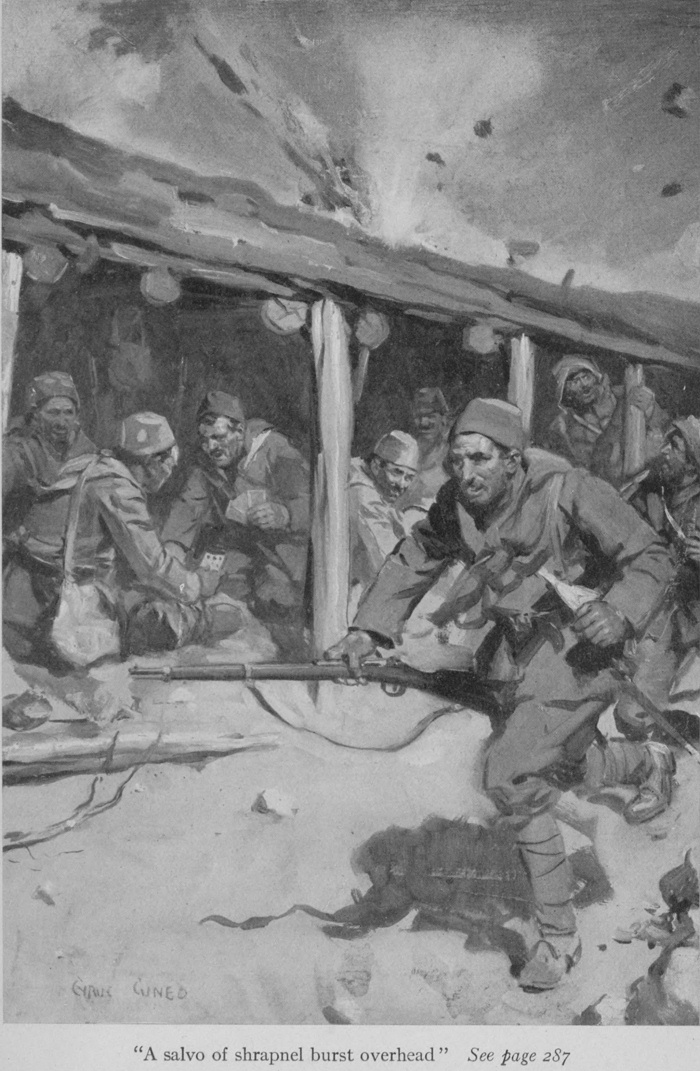

"You are right, Hamdi," said the Centurion, "those are Bulgars. Give her all you can." Hamdi's only reply was the monosyllable "Pump, pump." This referred to the Durkopp

![]()

215

system which required the passenger seated beside the driver to pump petrol up into the feed pipe when any special effort was wanted on a hillside.

Many years had practised the Centurion in estimating distances. The Bulgars had two miles of up-hill to gallop on horses that were probably tired. The car had about half a mile of stiff climb in front of her. She was doing her best, and she was a kind car; but a hillside was her weak point. The Centurion could see that it was going to be a close thing. Hamdi, who was staunch to the backbone, set his teeth and nursed his engine up that hill yet, pump the Centurion never so rapidly, the beat of the engine became slower and slower. To the Centurion it seemed that the car was only crawling. Already the horsemen had covered half the distance. There remained what seemed to be an interminable height of road in front. The time was past for exclamations. Hamdi, from moment to moment, cast a quick glance to his right. As the machine crawled

![]()

216

slowly on it seemed that the horsemen were certain to overtake her. The Centurion looked anxiously back at Jamal. He was lying back peacefully unconscious of the danger that was threatening him. Jamal, dressed in his volunteer uniform was a heavy dead weight to the Centurion at that moment. The presence of a Turkish soldier in uniform in the car would be difficult of explanation when they fell into the hands of the enemy.

There was nothing now that Hamdi could do to get a better pace out of his engine. Already the Centurion could hear the chafing of strained leather and the heavy breathing of the pursuers' horses. "Thank God the horses are blown," was his mental conjecture. There only remained now about thirty yards to climb, and yet it was the steepest of them all. Moreover the car was moving so slowly that it almost seemed to be stationary.

Shouts from the pursuers were now audible. They were yelling to the car to stop. Five yards more and the car began to feel the level

![]()

217

of the summit. She was picking up. The Centurion gave one look round. He could see the whites of the eyes of his flat-capped pursuers. In less time than it takes to write it the crest was collared and passed. As if by magic the car picked up impetus, felt her power, and was dashing down the slope. Five miles of this pace and all pursuit on horseback was unthinkable. There remained the rifles. The Centurion cared nothing for the rifles of men who for two miles had been riding an up-hill finish.

Never had Hamdi driven as he now drove the car down that incline. It was not a metalled way. In places she simply bounded from rut to rut; she swayed backwards and forwards, now on two wheels, and now on one. The wretched Jamal, knowing nothing of the reason for the haste that had so rudely broken his slumbers complained weakly of the pace from somewhere in the hood to which he was now clinging. A mile below the summit there was a temporary plank-bridge across a

![]()

218

sluit. Hamdi remembered it, but he dare not touch his brakes. The bridge was a rotten affair and its breadth was barely more than the span of the can Hamdi set his teeth as he swerved her on to it. She slithered, then leapt like a springbok, and, God only knows how, was over. The planks cracked and fell away behind her.

Once over the bridge the Centurion turned round to see if the pursuit was pressed. The Bulgars had given it up though they were busily dismounting and disengaging their carbines for action. The Centurion never knew if they fired, for at the pace Hamdi took the car down the remaining five miles of slope, the immediate circumstances were far more terrifying than the chance bullets of indifferent riflemen whose hearts must have been pumping a full twelve to the dozen.

An hour later the car was descending into Rodosto town. It was observed that there were now three Turkish warships lying in the roadstead.

![]()

219

As the car rounded the bend that brings the road into the town, one of the warships in the Bay fired a heavy gun. For the moment the Centurion thought that a warning shot had been fired against the car. Then Hamdi suggested in his nonchalant way that it was probably the midday gun. As, however, the sound of a shell bursting well inland followed his remark, it was evident that the gun was fired by the Turkish sailors against some target in the direction of the Muradli road.

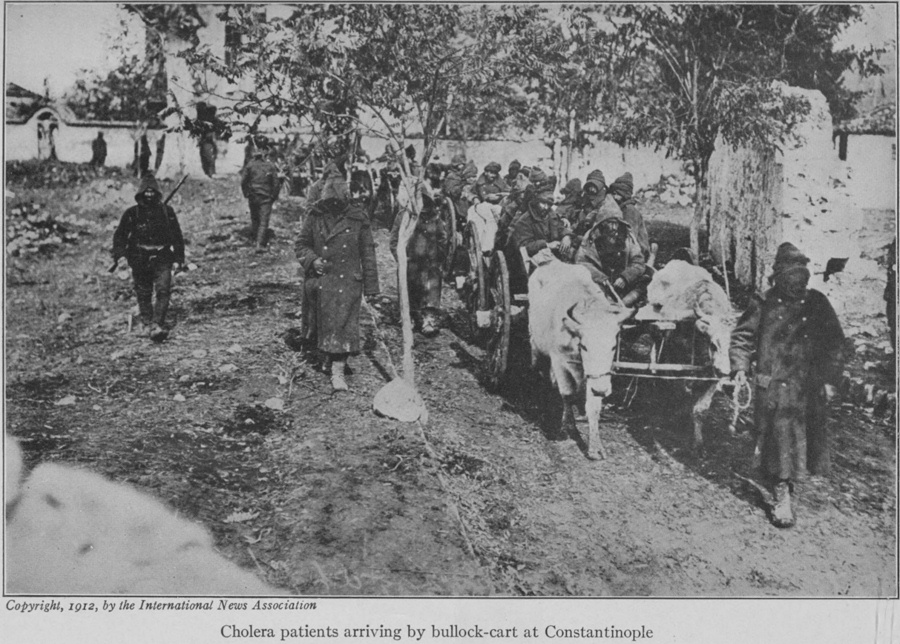

The Centurion returned to Rodosto to find the township convulsed with another of those paroxysms of terror which periodically seized upon it during the period that the Bulgarians were expected. As soon as the car was lodged in the han, he made his way to the British Vice Consul. The firing of that one shot by the Turkish battleship had put the nerves of the whole town on edge. The story that the Vice Consul had to tell was that the Kaimakam had gone on board one of the Turkish ships and had resigned the conduct of municipal

![]()

220

affairs to a Board of Christian residents. Early that morning, villagers had come in with information that a mixed force of Bulgarians and Servians was three miles out on the Muradli road, and that the commandant had summoned the town to surrender.

The leading Levantine residents, advised by the senior Greek ecclesiastic, had, therefore, taken upon themselves to go out and interview the invaders. Four of them, dressed in their Sunday best, had hired a phaeton and had proceeded along the Muradli road to implore the Bulgarians not to press matters in the confines of the town, as they had certain information that if any such attack was made, the Turkish warships would bombard the town.

When the Centurion reached the town, these worthies had not yet returned from their mission. As far as other news was concerned, the Vice Consul reported that nearly all the military stores had now been removed; that the town was practically cleared of soldiers; the gendarmerie had whipped up all the fugitive

![]()

221

refugee deserters, while a couple of Turkish boats had been sent to begin the transport of refugees across to Asia.

The Centurion himself was very little concerned with the affairs of Rodosto, his one object was to find a steamer sailing for Constantinople that would take his car back to the capital. He handed this business over to the Vice Consul who was also agent for the leading shipping firm in the Levant.

Shortly after midday the reason of the shot fired by the Turkish battleship was disclosed. Four very frightened and out of breath parlementaires returned from an abortive mission to open up communications with the enemy. It seems that after the Kaimakam had retired from his duties on shore, the Turkish naval commandant was informed that the Christian Levantines had started their deputation to carry "bread and salt" to the invaders. Under martial law, the naval commandant, being a post captain, was ipse facto, in both chief military and naval command of the town.

![]()

222

Not unnaturally, he resented the attitude of these weak-kneed Christians in toddling out to endeavour to make arrangements with the enemy. He, therefore, when his signalmen saw their phaeton toiling up the Muradli road, ordered a persuasive round to be fired in front of them. There never was a quorum of men who more quickly took a hint. The shell burst about half a mile beyond their carriage. The horses were immediately put about and brought back to the town at the best pace their sorry condition would permit. In reality, it is doubtful if any Bulgarian officer of sufficient rank was there to demand the surrender of the town, or yet within twenty miles of Rodosto. It is probable that one of the bands which were doing eclairage for the Bulgarian General Staff, and predatory missions for themselves, had hoodwinked the peasants, who brought the news, with some cock-and-bull story about their strength and demands.

The advent of the Turkish warships and the putting ashore of a strong naval landing party

![]()

223

had worked wonders in the commercial quarter of the town. The Centurion had no hesitation in saying that out of all the Turkish services with which he came in contact during the war, the only one that showed any approximation to a European standard of smartness and address was the Navy. Both officers and blue-jackets of the landing party were smartly turned out. The moment they were put ashore, they mounted sentries over all the Government material remaining in the military department yards. They picketed the main thoroughfares of the town. There was no doubt that the naval officers, as long as they were ashore, intended to control all matters that appertained to this final embarkation of the Government stores. It is not saying too much to suggest that this very marked difference in the efficiency of the Navy as compared with the system existing in the army, is entirely due to the British naval instructors attached to that service.

The naval commandant intended, as long

![]()

224

as he was carrying on his embarkation duties, to keep the enemy at a distance with his heavy ordnance. In order that his gun firing might be accurately directed, parties of bluejackets were landed and sent to observation points on the summits of the hills that command the town. Here the telegraphic wires were adapted to the portable telephones that the sailors brought with them and the observation posts connected up with the military pier from which point the messages were semaphored to the ships. The difference in executive capacity between the two services was here brought into strong relief, for the Centurion had seen the army in the field without telephonic communication of any kind. Even though telephones were lying idle with the reserves, the officers in the firing line were absolutely without means of learning what was happening on either flank.

Although perfect order was maintained at the Military Pier, yet no attempt was made to regulate affairs at the commercial wharves.

![]()

225

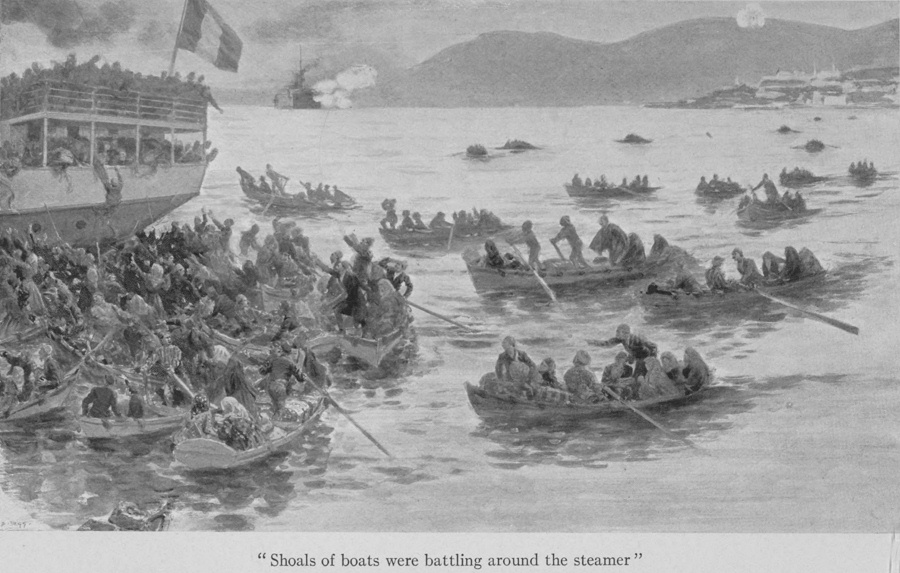

The firing of that signal shot from the flagship was responsible for another wild rush to the waterside. The Centurion had never believed that such epidemics of panic could seize upon a populace. For days the commercial jetties had been packed tight with crowds of refugees, who, camped on the quays, were content to await the arrival of some vessel to take them across the water. The apprehensions raised by the report of the big naval gun roused this hitherto placid medley into a state of frenzy. To them was added a wild rush of the town-folk. The scenes on the jetty were pathetic without parallel. The Greek boatmen knew the value of their services. They paddled their boats away from the landing stages and drove outrageous bargains with the frenzied crowd. This miserable picture was not confined to those of the poorer classes. Well born and gently nurtured Turkish ladies, forgetting the traditions of the harem, bareheaded and wild-eyed, beat their breasts or clasped the rough knees of the boatmen in

![]()

226

their frantic terror. Rude men hustled these cringing beauties from their path as they dragged their screaming children to the ships. Boatmen slashed at the crowd with their oars to beat a passage for those who would pay their exorbitant demands. When a boat drew to the quay-side demented mothers would cast their infants into the mass crowding the thwarts, and then leap blindly after them. Many were roughly pushed into the water and left to drown unless their rescue was worth a price. It was unbelievable that men could be such brutes; but the Levantine Greek has no soul if there be money in the scale.

That night the Centurion enjoyed the hospitality of the Vice Consul. The arrival of the express packet from Constantinople brought a surprise. On board the little steamer were Jew's Harp Senior and the Dumpling. They had come ostensibly to retrieve their Panhard. It is conceivable, however, that they were, professionally speaking, concerned at the long absence of the Centurion.

![]()

227

They were full of information. In the first place they had covered themselves with journalistic glory. Having caught the Austrian packet, as has been described, they immediately took ship at Constantinople for Constanza. There on neutral ground they had settled down to write and despatch the long and graphic cables that had made each famous. They both had received congratulatory messages from their papers. None deserved this more than the Jew's Harp. He had taken inordinate risks and had suffered the utmost privations at Lule Burgas.

The information they had brought of the other adventurers was instructive. They were nearly all back again in Pera. The Bosniak Shepherd was at his wits' end. He said that he could manage the Frenchmen and the Germans, and even the Russians, but the Englishmen were beyond his power. He washed his hands of them.

The news from the various seats of war was astounding. The military reputation of the

![]()

228

Ottoman Army had come tumbling down like a pack of cards. The Greeks were on the point of taking Salonika. The despised Servians had defeated Ali Riza Pasha and were not only in occupation of Uskub, but were marching triumphantly through Albania to the sea. The only bright spots upon the Turkish horizon were the garrisons of Adrianople, Scutari and Yanina. Beleaguered fortresses, however, even if they do make a gallant resistance, are, at the best, but a sorry consolation for loss of territory and reputation. In three weeks Turkey had lost by right of hostile conquest her European provinces, almost in their entirety. The thing was too stupendous to be readily believed.

It is not difficult to find the reasons for this unprecedented debacle. They may be conveniently divided under two heads. These are inefficient administration and inadequately trained material.

On both these vital questions, this trouble in the Near East presents to military students an

---

Turkish veteran infantrymen

![]()

229

object lesson of far greater importance than any campaign that has happened since the Franco-German war. There was much to be learned from the Manchurian campaign, but the elements there engaged were more or less equal, from the point of view of armies organised on the basis of national service.

Taking the first head, the lessons of the Russo-Japanese war demonstrated a triumph in staff direction, backed by a technically-trained and splendidly-led professional army. It has already been shown in the present narrative how the administrative incapacity paralysed the entire system of the Ottoman resistance. As far as the English nation may hope to profit by the lessons of this truly remarkable Balkan war there is not much that we need take to heart in the matter of army administration. The competent military authorities of the British Empire have long ago realised, and as far as national acquiescence in their views has permitted, have strained every nerve to bring up to date the administrative departments

![]()

230

of the army. That the scope allowed to them is small, is no reflection upon the Imperial General Staff. As an observer of some experience, the Centurion is of the opinion, that for its size, the British Army is as well administered as any in the world. Taking the South African war as an example, the administrative faculty of the nation was admirably demonstrated. This, it must be remembered, was at a period before the modern requirements in warfare had been truly estimated. In spite of the fact that the administrative machinery was only designed to cater for an army of 50,000 men and had to be expanded to deal with a situation utilising five times this number, the British army in South Africa was without doubt the best rationed, clothed, and administered army of any size that has ever taken the field in the history of war. This view being accepted, and the General Staff having profited by the stupendous experiences of the Boer war, there is no reason to doubt that, given national support and adequate

![]()

231

material, the capabilities of the British army on an administrative basis should be unrivalled.

It is not necessary, therefore, to deduce lesions on this head from the experiences in the Near East, further than to remark that they have endorsed to the full every instructional theory that has been put forward by the British General Staff in its unsupported struggle towards efficiency during recent years.

When, however, we come to the other head, we are upon the fringe of an enormous, and it may be said, a vital question for the British Empire. The Turks in the consummate conceit bred of their congenital stupidity believed that because they had been able to overthrow their own reigning dynasty by force of arms, they were competent to handle any military contingency that might arise. With Tartar obstinacy they were content to stake their all upon their hereditary traditions as a fighting race, garnished with the modern appliances that could be purchased in the best arsenals

![]()

232

of the world. In the immediate circumstances of the menace of the Balkan Allies, they had been actuated by a sublime contempt for the virile neighbours that had at one time been their vassals. They plumed themselves in the stupid belief that as a fighting race they possessed some occult superiority before which their Balkan enemies were bound to crumble. In this belief they were encouraged, how sincerely it is not known, by some of the best military thought in Europe.

In this spirit of confidence they fell into the error which is so common in nations where self-confidence is a malady: that given a small steel-point of efficiently trained troops, it is possible to fill up numbers with the partially trained ; that after the first clash of arms, given a martial race, there is time and opportunity to fashion the pig iron behind the first line into serviceable steel.

Never was there a greater fallacy. Never in the history of war has the danger of employing inefficiently trained and indifferently

![]()

233

officered troops been more poignantly demonstrated. Take, for instance, the pathetic picture of the defeat of the left wing of the Turkish armies in Thrace. Here you had the First Army Corps and the Fourth Army Corps with the initial nucleus of their battalions formed by the inclusion of all their first-class Redifs. These were the only soldiers of any quality in the Empire. This ban of Redifs had practically been absorbed into the first line owing to the many difficulties in which the Ottoman Empire had been embroiled, since the Young Turks had entered on their fatal endeavour to run the Constitutional steam-roller over the Empire's many dissenting nationalities.

These skeleton battalions had to be brought up to strength, not only by enrolment of second class reservists with but a shadow of training, but also with men who had been taught the manual exercise and the goose step for the first time within a fortnight of their marching to meet the enemy. What was the result?

![]()

234