III. THE MIGRANT WORKERS

Galichnik 71

On a wonderful morning in Bitolja, at around five o'clock, I was inserted into the only empty space, narrow as a sitting tub, in the back of the tiny car.

The vehicle was like a small fish. The two front seats were occupied by the young, curly-haired driver and stocky Kocho born in Smilevo, (my voluntary guide).

The precautions, which the two had taken against the August heat, were quite different, but nevertheless, they suited them both. The pretty straw Girardi fit the lively young man well, while the dark, leather hat almost merged with the dense, stubby beard of the plump Macedonian, both ends of whose short, thick, and bristling moustache were removed away from each other, towards each end of the pole, as two rivals after an argument. Because of the dense as bushes brows, his eyes looked like a heap of oak branches, divided by a protruding rock — his nose. No other type of nose could be found here.

We spend on, while our heads were occupied with . . .women.

I unwittingly betrayed not only the secret, but my clumsiness as well. Even in such travel-notes the reader prefers to be kept in suspense. And why should I share right away something that I did not learn all at once myself? I know that I awaited Sunday's Smilevo trip eagerly, since I had heard that the most beautiful Macedonian costumes were worn there. I also knew that the good Kocho M., otherwise a contractor and a builder, was going to see his wife and his daughter. But I knew nothing of the young driver. My curiosity had been aroused by his dreamy eyes and by his words, before we had started, when he had refused to have a cup of coffee with me.

"Thank you," he had said with a smile. "I can't. I haven't slept most of the night. I had awful nightmares. During our trip the benzine burst twice into flames. I don't dare increase my excitement."

![]()

63

I hadn't been surprised by what he had said. It wasn't for the first time that a driver refused something stimulating or refreshing. The tough local boys were forced to drive like evil spirits (the roads didn't allow them to drive like evil spirits (the roads didn't allow them to drive in any other way) and no wonder that their excited minds flew forward in the distance, even at night, when they were sleeping.

This time I was probably mistaken. The young man had not slept for another reason, which only he, who allows himself to be patiently lead across the desert of landscape descriptions, can learn.

We finally lost Pelister, whose wide, and beautifully modeled and painted slopes, with the drowsing Bitolja and its slender minarets, presented a harmonious background of gentle hues and whose end, thank God, was visible only with its large proportions, and not in detail, which would have delayed us. We were speeding towards the northeast, under the bare, dry mountain slopes, glimpsing the Pelagonia plain, which was transformed into a sea of corn, to the right. In the distance ahead, the valley was enclosed by a group of basalt peaks near Prillep.

We covered everything that we saw with clouds of heavy dust.

We turned left, to the northwest, in an elongated valley, in which there wasn't even a trace of a forest. Burnt grass merged with the light stubble-field and the dried up soil. A great sadness had covered the otherwise pleasant picture. Thousands of golden-grey shades glittered under the blue-green sky. The outlines of a shepherd and his flock were disappearing; everything was covered with the same colours and shades. If it weren't for the alert dogs, or rather their noisy manifestations, may be we wouldn't have noticed anything.

We passed through the village of Koukourechani, where girls, carrying water in the early morning, unwittingly formed sweet groups. We passed through the next village (with a small number of inhabitants), speeding on the wide, comparatively good road towards the bluish, afforested mountain, whose ridge was gilded by a small, ripened field.

Kocho turned around and said, "Smilevo is over there", and his eyes sparkled.

The road became narrower and turned towards a narrow, overgrown valley. Its bottom was a lush meadow, its slopes thick coats of shady trees. We crossed a narrow-gauge rail-road, built quickly and not badly during the World War by the Germans, of which the people

![]()

64

in Macedonia, from all the armies that had passed through or had stayed there, had the best memories. We regretted that it had been left to the mercy of fate (in some other places the same rail-roads worked excellently).

We passed through a Turkish village, in which only a single minaret had managed to pierce the dense trees, and on the by now broken down road, with the sad moaning of the car, we started climbing up towards Smilevo, which glistened up in the distance. We arrived at the end of the valley, surrounded by a few deep ravines, in which an interesting, terraced village was embedded. We looked towards Smilevo as an actor looks towards an audience. All the houses, without an exception, were one-storeyed. It was a village like a town, the more so as there were no fields, and consequently almost no farm buildings.

It was the typical local picture. The whole male population was scattered all over the world, seeking bread for itself and its family. Smilevians were by and large "masters"-master-masons, master- carpenters, and sometimes, when someone showed greater skill, builders, or even contractors, as was the case with Kocho. In such a way, someone might earn a fortune, which would not alienate him from his home or his family. They would always return, and not only to improve their houses but to contribute with their savings for the construction of churches and schools as well. Everywhere in the Balkans one met "Macedonians". Some, who worked as lumberjacks, carried bucksaws on their shoulders and axes in their belts, while others opened shops. Others even crossed the Atlantic Ocean. I met some who had traveled to quite a few places. They called it profit. "Going on a profit" was a typically Macedonian expression. It reminded one of the Russian word "pechal" [*], which meant sorrow or grief. Kocho was constantly "gone on profit", but not far away — he worked in Bitolja. He was coming to see his family, which was not on vacation but lived in Smilevo permanently.

After the bridge, the car stopped and Kocho picked up the provisions, which he had bought in Bitolja and led the way to his house. We climbed vehemently, but not very quickly.

We stopped in front of a one-storeyed house. The old father and the young wife, with one of the children in her hands and the other in a

*. Profit = pechalba in Bulgarian. Translator's note.

--------

![]()

65

"kroshnya" (cradle), happily greeted the head of the family. The "batsuvane" (kissing) was endless. The little girl "batsila roka" (handed out her hand) to her father.

The two of us, myself and the driver, formed a silent background to the whole scene. Finally, we also "batsime roki" with the others, greeted by the hearty "zdravo"!

We entered into the ground floor (the "pondil", where different tools were kept) and climbed up the stairs to the first floor, where a "razboy" (loom) and a chest with clothes and different other objects were to be found in the anteroom. Kocho guided us to a bright room with an excellent view of the amphitheatrically situated village. The main piece of furniture in the room was the huge, wide bed. The "mindhers" (low divans) with cloth and reed carpets were along the walls. In the middle of the room there was a table with a couple of chairs.

Kocho devoted himself to his family and his house duties, while I remained in the room with the driver. We walked over to the window and watched the landscape. The air was fragrant and our hearts melted. The young man stated his admiration for the beautiful picture before us. We started talking about each other. I liked his young eyes and the enthusiastic and cordial voice with which he spoke. He told me about himself. He was a Serb from Shoumadia (in the southwestern corner of the former Serbian Kingdom). Still a child he was drafted in the army. When he returned, he found no one. Part of his family was killed and the other part had scattered away. He had heard nothing of any of them. He was alone in the world (maybe that was why he trusted me, the foreigner, so much). His name was Stahne and that was how he wanted me to call him.

Kocho came back to show us around the village. He was proud of it.

First he took me to the church, which the inhabitants of Smilevo had built not long ago by themselves, using their own savings. I was most interested by the ritual, which was being performed inside. There was a baptism. The married women with the infants and their godmothers were alone responsible for the preparations of the numerous baptisms. They handed out sweetened wheat, which everyone present had to taste.

I was amazed by the magnificence of the dresses and the artistry of the local embroidresses. The yellowish-white woolen dress was decorated with wide crimson strips and high, heavy, overlaying embroidery.

![]()

66

The light veils merged with their heads. Large silver coins glistened on their foreheads, their breasts, and their aprons.

Before asking Kocho to lead me further, to show me the "charshiya" (square), I was presented to his neighbours, who were so proud of the fact that they had been dreaded enemies of the Turks. Smilevo had twice been destroyed by them, the second time during the glorious Illinden uprising in 1903.

It was a subject of which no one spoke, of course. The uprising, kindled by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, had had a goal to liberate Macedonia, as a land whose Slavic population, with the exception of an insignificant Serbian minority, considered itself Bulgarian, and now, when the land belonged to Yugoslavia, no one dared even mention of the past. (Of course, in our country it is well known that one of the founders of the IMRO, Damian Gruev, killed by the Turks in 1906, was born in Smilevo, and that during the uprising, its headquarters had been situated there).

After a visit to the mayor, we went back home. An excellent soup had been prepared from the beef that we had brought. The meat and vegetable dish was also wonderful and so were the Bitolja bread and the watermelon, while the excellent wine gave a special flavour to the feast. Afterwards, Kocho contentedly flung himself on the very wide bed and offered both of us to join him. There was more than enough space, but we refused. Stahne said that he wouldn't be able to sleep, while I wanted to jot down a few notes what I had seen today.

I took out my notebook and was almost ready, when I had to stop, through no fault of my own, though. Stahne sat beside me and started talking. He spoke of all sorts of things, but when Kocho started snoring he became peculiar and gave way to his feelings. When he was finally certain that Kocho could hear nothing, he sat closer and started revealing his innermost dreams to me, as to a father-confessor. It turned out that he was in love and that he trusted me so much, that we wanted to confide his sweet pain to me.

"I will tell you something, sir," he started excitedly, "but please, don't ever mention a word to Kocho. ' (As if we had been long-time friends with Kocho and met every day!) He went on, "Don't give me away! I have a girl. She's a beautiful and good girl. Educated as well. She has studied in Istanbul. She's a baptized Turkish girl. She sings wonderfully. Maybe you've seen her. If you've been to the Moscow restaurant some evening, you've probably heard her sing. She also

![]()

67

loves me. She said so herself, frankly, and I believe her. I will be very happy if she stops singing. But she doesn't listen to me. I want to live with her in a beautiful place, like this far away from the whole world! I've decided for a long time to propose to her but I always lose my courage. Day and night, I always think of her. That's why I have nightmares. When I saw you writing, it suddenly came to my mind that it's better to write all this to her. I decided to write a letter to her. Would you lend me your pen and a piece of paper. I'll write all this to her right away. And please do come tonight! I will be very happy if you see her and tell me your opinion . . ."

I was surprised, almost dismayed. I could have given my opinion to the young man right away, but I was certain that it would not have helped him. Like everyone who is in love, he wanted me only to agree with him. I did what I could. I gave him a piece of paper and my pen, flung myself beside Kocho and fell asleep immediately.

I don't know how long I slept and whether it was I who nudged Kocho or the other way around.

But both of us stood up. Stahne was standing pensively by the window. The inkpot and the pen were on the table. It was three o'clock. Kocho motioned that we should be on our way. He went to see his child while we prepared ourselves. Stahne whispered pleadingly, "Please, not a word to Kocho!"

We thanked the family for their hospitality and went to prepare the car.

Suddenly Stahne stopped. He pointed towards the opposite slope. Some girls were singing and playing in the garden, their red scarves were clearly visible on the green background and their beautifully lined veils were waving from their heads. "What beauty!", shouted Stahne. "I want to live with her so much!"

He was woken from his daydream by the sound of footsteps. Kocho was coming behind us. We moved on. Stahne only added, "Come some evening, if you can."

Soon, the car was speeding across the bridge and we all turned around to say good-bye to Kocho's family, by waving our handkerchiefs. And Kocho touched his eyes several times, as if something had gotten in them.

That evening, I was walking with some acquaintances in Bitolja, when someone greeted me. It was Stahne. "Good-bye," he said. "Good-bye," I answered.

![]()

68

Unfortunately, that evening my friends would not relieve me of their company. I regretted it, but I decided to excuse myself to Stahne the next day. But I didn't find him. The devil had taken him away again. The next day I left the region and so my memory was left without an ending.

Upwards, of course, and at a height of 1500 meters!

When on the ninth of July, 1927, at dusk, we arrived there from Skoplje (150 kilometers away), I whispered, "At last!" and came out of the car battered and shivering from the cold, since the latitude, the same as Naple's, had little value at such a height.

And when I looked over the rocky surroundings and the unfathomable precipice, in which 400 shabby houses with slanting by 45 (and more) degrees foundations stuck out, I whispered the same words for a second time.

I had two reasons to do so.

We started early, at nine o'clock, and therefore had enough time for our journey. But at first we had traveled in an awful wind, in which we could have even turned over, and then through the Tetovo-Gostivar valley, which was more than thirty kilometers long, with a road, taut as a rope, which was well below the height of the surrounding mountains and was therefore covered with dust. Secondly, we had constantly passed by cars, and with philosophical calm had watched the angry drivers, who were mending their inner tubes or inflating them, and whose poor example, unworthy of being followed, attracted our own vechicle irresistibly. It was so run-down, by the way, that after each jolt it limped a few times and stopped. We got off and noticed that the driver also limped. Nothing could calm him down. Looking at the two cripples helped us accept the facts more easily. And it was the only sensible thing to do, since the next mishap came soon. After Tetovo, the tyre were punctured for the second time, and after a "short interval", for the third time. We could do nothing, except to leave everything to fate and to the driver, and sit down in the dirty ditch by the road, in order to wait helplessly for the good fortune that would rescue us from this miserable situation.

The 2700 meter high Shar mountain had endured watching us mercilessly for more than two hours. It must have been amused when

---------

![]()

69

cars shot by without reacting, in most cases, to the signs we had made.

What a pleasure it would have been to sit there under different circumstances, surrounded by the high mountains, at whose foothills, among the dense trees, Moslem villages with slender minarets nestled as a group of wood-nymphs, and to watch the Albanian caravans and the tanned faces, and the variegated, although mostly white, costumes. Our sad Czech song pressed itself upon our lips: Oh, there is not, there is not!

A Turk came towards us. He was going in the opposite direction, in an ordinary manure cart, but my comrades had flung themselves at him, with entreaties at first and with insistent persuasion after that, until they had made him turn around and take us with our whole luggage. My heart was beating, my limbs trembling and my teeth chattered every time the cart jolted, but the thought that we could not puncture a tyre made everything easier. After two and a half hours we reached Khostivar (why should we exert ourselves instead of using the Czech Gostivar?) uneventfully, and when we found another car right away, our greatest concern was removed (how were we to continue our journey).

Of course, very soon, another one came up: how were we to overcome the last twenty five kilometers? Two years ago, it was possible to cover half the distance along the winding road, until Mavrovo Pole, with a team of horses and the rest on horseback or by foot. That part was adapted for motor cars, but very hurriedly, since it crawled upwards with numerous hairpin bends. It also passed through deserted places. In the eighties, Gopchevich was armed to the teeth when he traveled in these parts, and really, after the war the neighbouring Albanians had often made raids, not hiding their evil intentions towards the local people. And what would we have done if it had happened to us? Had we set off in order to pop off again (this time not our tyres)? What would we do in dark? We started at half past five!

Islam Ouseinovich, who fortunately kept his car under the enormous tree in the center of the square, naturally praised it (it was really beautiful) and assured us of his dexterity, which he really possessed. But he was only fifteen years old!

But what could we have done? We got into the car. Thanks to God and Allah, we arrived without any accident. The young man and his car proved equally excellent. On the sharpest bends, whose radii were

![]()

70

insufficient, he had to maneuver three times in order to align with the road's axis. He had only laughed whenever we looked down into the greedy precipice. He had even remembered, the vagabond, to show us the place where a week ago a car had fallen off the road into the precipice, so that he could manifest his skill better.

My first "at last" was for all this. The second one was for Galichnik itself.

For the last two years everyone had recommended it to me. It was the center of the Galichnik Srez (district), whose population was quite unusual, with incredible contrasts and endless frivolities. The cosmopolitan men, in addition to their Macedonian dialect, spoke many of the world's languages. Every year they returned back home, where pride and magnificence radiated from their ancient costumes, and where the costumes and the rites were preserved, as maybe nowhere else among the Slavs. The region was poor. It had neither fields, nor gardens, since it was at the very end of the vegetation zone. It had no beggars, but it had maybe twenty millionaires. The rocky town looked like a small village, especially now, when the district government was moved below, in Rostousha.

"At which inn should I lodge?" I had asked two years ago, intending to come here.

"There aren't any inns."

"Who will put me up, then?"

"Anyone. Whoever you go to. But there's no use of your going now. You must come on St. Peter's day (June 29). Then the Galichnik men return from abroad and the weddings begin (once a year), sometimes as many as thirty or forty. There is a lot of revelry, with rituals, which goes on for a full week."

So here I was, two years later, heading for that day. I didn't know where I was going to stay, but when I got off the car I was surrounded by such affable people, that I will never, until the end of my life, forget their faces. In a moment I found myself under a friendly roof. The next morning, the district clerk arrived from Rostousha to offer me his assistance while I stayed here.

That was how my week-long visit began in this worthy of wonder place, of which I had dreamed so much and of which my memories are like a fairy tale.

![]()

71

If we had arrived from the south, i.e. from Radika, a tributary of Cherni Drin, and along the steep valley of the Galichnitsa river, we would have seen Galichnik from a height, as a chandelier, stuck on a wall, shining on the huge rocky ledge, whose eloquent name Govedarnik served the wide mountain slopes as an advertisement in a big city. Only it wasn't necessary. The excellent dairy products had managed to find their own way throughout the world (as far as Africa and America).

The Czech meaning of the name should not confuse us, of course. [*] There were no cattle here, just as they were scarce all over Macedonia. And the meat wasn't of very good quality either. A cow in Galichnik was a rarity, one might say a real diamond. And its hardness and size were that of a diamond too. A fellow countryman of ours, from Skoplje, had been hunting in the region once. He saw a deer, but when he drew nearer he found out it was a car. When he came still nearer saw it was a cow.

Only sheep were raised here. Before the war Galichnik had 70 000. The pastures were spread over the ridges for more than twenty kilometers, as far as the Shar mountain. Milk, excellent cream (smetana), and two types of cheese: yaflia (a sweet cheese) and yako (a sharp, salted cheese) were produced in the mountain dairies. Hard kashkaval (a yellow cheese) was produced in a few factories (by Greek workers) and exported overseas. Suet, which was consumed in Greece, was produced here as well.

Otherwise, the harsh environment gave its inhabitants nothing but fuel, excellent water from the abundant springs, and healthy air.

Galichnink's foundation were built in amphitheatrically, in the steep rocks over the 400 meter wide slope, but its bases were the soft, wide pastures, with which we were partially acquainted when we topped the 1600 meter high ridge Bister, which left an unforgettable impression on us with its view.

For a long time we were driving through a gorge sometimes shallower and sometimes deeper, of whose dimensions we had no idea, since we had nothing to compare it with; there was not a tree or a building in sight. Everywhere, there was only short grass, resembling goats; hair. The undulating country seemed to be coated with green velvet. The green had almost no shades and we were not able to

![]()

72

distinguish the horizon from it. Here and there, a dwarf pine could be seen.

The quietness of the country had overpowered the noise of the car and penetrated our souls with its absolute monotony and desolation. We were so overcome by grief, that a burning desire to remain there and erase the solitude welled up in us. But at the same time, an opposite feeling was aroused by the question: what were we to do there? The demonic power of solitude had played with us, shifting our thoughts from pole to pole: it had awakened nature's law of settling and at the same time, the instinct for self preservation. Oh, hypocritical Horror Vacui! We had left behind silent places, which seemed to be calling to us: "Do not leave us." But the car heard or saw nothing. It kept racing on. How we had relaxed when we had glimpsed a flock! The immovable figure of the shepherd turned its gaze towards us. What were his thoughts? What were they telling him of us?

The shepherd held a wooden flute in his hands. The music was a real gift for the young man. It meant that he was not alone. Thanks to the flute he had someone to talk to. It was probably his own soul, to which he listened. But was it not in it that one saw the image of all mankind? Wasn't the soul of all mankind always one and the same and just because of that common to all (since as it passed from the matured bodies into new ones, the old soul made way for the renewed one and it continued further on, new, fresh, eternal). And didn't it always converse alone with itself, often with a fateful misunderstanding? Wasn't the whole spiritual activity of mankind only an amazing, endless monologue of the entire human soul, a sum of melodies, whose mysterious rhythm and harmonious and disharmonious intervals cultural history has sought to appraise and to understand?

And here, in this world, doesn't this uniform human soul, just as the shepherd's, feel its abandonment, which makes it look around, just as the shepherd had looked after us, and light the universe in search of a friend, a strong and powerful one, and when it thinks that it has found him, it calls him God?

The Galichniks had only that one pasture now. Once they used to have many more. During Turkish times they could go down to Salonika, while the Greek shepherds, when their lowlands had dried up in the summer, could come with their flocks up in the mountains. This magnificent migration of the countless flocks, with hundreds of thousands of sheep, took place in the autumn. (Poor soul, he, who

![]()

73

chanced to meet them on his way!). After the war everything had changed. But only one-sidedly. The Greeks could still come freely here, while the local people couldn't go there any more. The Serb Rista Stoyanovich, in "Sbornik Professorskago Drouzhestva" (Skoplje, 1922) critisized the Belgrade government that it paid more attention to foreign policy than to the economy of the country, which it had left to the arbitrariness of Greeks and Albanians.

Maybe Galichnik itself owed its founding to this millennia-long movement of shepherds.

The people of Galichnik believed that its name was derived from the Galik river near Salonika, which was allegedly called so because of the Gauls, who had originally lived there. They had gone up to present Galichnik with their flocks. During such journeys, many of them had preferred to remain in the mountains. So the people of Galichnik were proud to be the descendants of the same Slavic tribe whose speech the brothers Cyril and Methodius had made the first written Slavic language. The Salonia dialect was really its base. It is a region which should interest us, Czechs, since the Macedonian speech contains many Czech words and peculiarities, not found in the Serbo-Croatian language.

Many necessities had to be imported from outside. Until not long igo it could only be done on horseback. The number of horses had reached 1200.

Time had passed and Galichnik ceased to be only a shepherds' own. The population had increased and the men had gone into the world. More than half of them were scattered over the Balkans, Europe, and the rest of the world, seeking work and livelihood. They vent abroad to make a living, or as they called it "on a profit" (earning their living abroad).

They never did any field work (since they didn't know how). But they could perform any other work thanks to their gifts. As milk specialists, they opened dairy shops, which they transformed into cafes or inns, or made oriental pastries, or became bakers, or carpenters, or masons. In that respect they were the Balkan's specialists. The chimneys and the built-in stoves in the Balkans were made only by Macedonians. The natives of Galichnik were also famous as artists. The nearby monastery Ivan Bigorski was well known for its grand and magnificent iconostasis, made of wood, with exquisite taste, by the local master Makari Filipovski; in Skoplje, one

![]()

74

could admire the iconostasis, amazing with its splendor made by the wood-cutter Marko from nearby Ghare. The local zographs (icon- painters), among whom the Fruchkov's family was a real dynasty, was well known. Their last descendant, who for many years had worked in Rumania, had drawn the mural paintings of the new Skoplje church on the order of the King of Serbia. I met him personally in Galichnik. The natives of Galichnik were also justly proud of their fellow townsman Parthenii Zographski, who in 1859 had become Bishop of Koukoush (now in Greece) and in 1872, when the Sultan had approved the establishment of a Bulgarian Exarchate (an independent Bulgarian Church), he had become Metropolitan of Nish, seated in Pirot, in the region of the former Serbian Kingdom, which after the Russo-Turkish war had been allotted to Serbia and was already Serbianized.

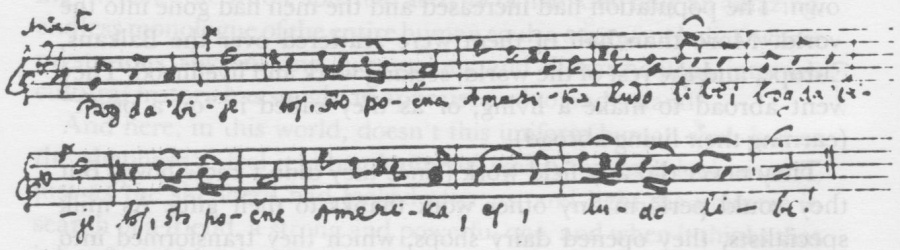

If the natives of Galichnik surprised one with the smooth transition from individual shepherdry to cosmopolitanism, their third quality closed the triangle in another surprising way: they traveled abroad, but they always returned home, to their families, with the fruit of their work. Sometimes, as on St. Peter's day, for a short while, and sometimes, if God willed it when they grew old, forever. Great happiness would ensue for the families then, quite unlike the grief at parting, which was expressed in the local song God punish him, who first went to America!

God punish him, who first went to America,

my dear, God punish him, who first went to America,

O, my dear, my dear!

At home, they quickly took off the "European" clothes and put on the narrow, white "bechvi" (trousers), the red, wide belts, the brown coats, the hooded cloaks, and the black hats, and started visiting friends and neighbours from house to house. Picturesquely dressed, they stood out beside their women.

![]()

75

One could speak any language here, Albanian, Turkish, or Greek, but also German, French, Spanish, Italian, English, and even Czech sometimes.

The Skoplje theater had decided, not long ago, to give performances in different Macedonian towns, but had been uncertain whether to go to Galichnik. It had been said that no one would understand the theater. A friend of mine, with whom they had negotiated, had answered, "We were able to watch operas and performances in Athens, Bucharest, and Paris, so why can't we see a performance from Skoplje." We were at his house and he showed me a picture of himself, a wide-brimmed hat on his head, riding a camel, with the pyramids in the background. We were at a wedding where congratulatory telegrams from different European cities and from Egypt (Alexandria) were read.

Such were the Galichnik people. Only God knew where they owned property (houses, hotels, fields): in Salonika, in Sofia, or in Rumania. They had ties with the whole world, but were attached to their homes. This loyalty was their moral basis. While they had become advanced and educated, they had been preserved both internally and in external appearance. They dressed as their ancestors had, they lived as one family, they did not go to law courts, and they placed promise above anything else. Such was Galichnik.

Now let us look at this archaic society in greater detail. Three young, pretty ladies, in most modern and economical (as far as the quantity and not the quality of the fabric was concerned) dresses and mikadas [*], had come with two officials from Skoplje, and while the men were taking care of their affairs in the village, they went to see the same family that we happened to be visiting.

They sat on the colourful divans capriciously, while their ideally kept hands were trying to hide their knees, outlined with anatomic accuracy beneath the high silk stockings, with the ends of their skirts. Maybe the mountain climate assisted this coquettish imitation of shyness with its cold reality.

All the womenfolk came to greet the guests. A whole line of heavy and grand old-time costumes stood as a wall against the strangers. Two different worlds were being opposed to each other.

With a trained sweetness and with the ease of dragonflies, the young Skoplje ladies greeted the Galichnik women, and after the

*. Mikada — A type of Japanese hairdo. Author's note.

![]()

76

ordinary eccentric questions, sat down on the divans in elementary postures, copied faultlessly from fashion magazines and from the theater, while the local women, matrons, with hands crossed on their wide, silver belts, continued standing freely, in a ritual pose, dignifiedly, calmly, and grandly, imitating the local customs. That is, they imitated nothing, because they had no intention to. They were obeying the command of centuries and ages with an instinctive obedience. The ladies, of course, were also obeying a command, the command of our present times, the contemporary curiosity and impatience, which were already dictating the motto of tomorrow — disregard. It was a far too quick overthrow of models, i.e. of modes, a constant revolution with all its cruelty, since one forgives everything but outdated fashion.

The immovable everlasting had met the fleeting instant. The basic difference between the two sides, though, was not the difference in clothing, but rather the difference in the personalities themselves, and this difference seemed to point out ostensibly, the lack of freedom in one of them and an independence in the other. But the strength of imperative and susceptibility was the same for both sides, only for one of them the command had been valid for centuries, while for the other only for an instant. That was why the outward appearance of the first could, and was, coalesced with the inner self in a whole, thus creating a greater individuality, not limited by the separate individual, but common for all generations, while in the second case no such period of time existed. Everything in it was changing quickly and the outward appearance remained independent of the inner self, and at the same time nothing occurred; at least nothing permanent. The conclusion from the first system was duration and grandeur, and from the second, ephemerally and short-lived temporariness.

Those that look upon the folk costume as just a fabulous dress, know nothing of it. The dress becomes a "folk costume" only then, when internally it is an inseparable part of the individual, and not just the personality of one person, at that, but of an abstract individual, well considered and fully created by time in its home atmosphere. Otherwise, the "folk costume", as primitive as it may be, is nothing but a rented masquerade costume, and he who wears it is nothing but a mask, notwithstanding that it may be beautiful or tasteless.

My words that the "folk costume" must arise from the personality itself and that it must be its internal component are not just made up.

![]()

77

In Galichnik, the young girl begins preparing her trousseau with her own hands from the age of eight. It is a "must" that by the age of sixteen she can sew and embroider eight shirts.

Such is the number of shirts she will need until the end of her life. Afterwards, she will change only the lower parts, while the breast part and the sleeves, with the embroidery, will remain. Plus that, she must possess "attires" (different types of clothing) of which the "wedding attire" alone costs 7000 dinars.

Therefore, the tender girl makes her clothes by herself. It embroiders according to the models, but also according to her skill and feelings, therefore with love and with all her artfulness. She works for her own future, and since she always does it in the company of older girls, who advise her, the girl is in a way in an art school. So no wonder that if in any of them there should be talent, works of art are produced, but still on the basis of the established school.

The girl here is a molecule of the whole. She is like a silkworm, which spins its own cocoon about itself. She is like the animal, which builds its own shell, like the fruit, which creates its own kernel. When later on the girl from Galichnik adds to her shirts a mintan (an undergarment), a klashenik (a dress with hanging sleeves), a koparan (a ladies'jacket), and a kittena skoutina (a bride's apron), all she had to buy is a wide silver belt, which she will need when she becomes a fiancé or a svirshenitsa (a betrothed). Will she not represent an organic whole and a single creature with all this? Will not everything that shines on her be only the end product of her inner essence?

In Smilevo the costume is basically the same as in Galichnik, only it is more perfect and richer. Someone in Bitolja told me that Belgrade was considering the possibility of sending a teacher there. So that he could learn something maybe? That also. But he will go there, officially, to raise and improve the level of art. And if he possesses any talent, he can only spoil everything, deprive it of the raw and individual charm what it possesses, and destroy the style, while the product will be mechanized, and therefore devalued.

Such a view on folk art is not, of course, a privilege only of Belgrade, but the intelligentsia of the whole world as well. It is not by chance that the expression "common people" is used with benevolent condescension and what it replaces the word nation in inappropriate cases, although it is the common people who are really the nation (i.e. the tribe, the clan) and create its essence.

Or are these international casts of Paris models, who have reached Galichnik, more representative of the nation than the local women?