V. VARDAR OUTLINES

Skoplje 103

Market Day—The Weekly Market 108

In the sloping yard of the old inn, which was in an our-of-the-way Skoplje quarter, near the Kourshoumli Inn, I heard the sound of horse's hoofs. Someone dismounted a horse and stopped behind me.

When one is seeking something, he rarely pays attention to anyone standing behind him. At that moment, I was trying to catch one of the gypsies, who were walking to and fro in the foreground and excellently filling in the picture, whose climax in the background was magnificent mosque. That was why I paid no attention to onlookers.

But the rider greeted me and I couldn't avoid him. Our of the languages in which I could answer in, I chose Russian. The stranger presented himself as a Serbian abbot of one of the many monasteries in the Skoplje Cherna Gora (a parallel ridge, three hours to the north of Skoplje, which formed the pre-war border of Macedonia)'

I had no choice but to do the same. I did not regret the short interruption, though. The energetic old man, whose kamelaukion was happily resting on his unruly, long hair, was smiling at me. With his agility, he managed to surmount the impression given by his black dress to such an extent, that it seemed to swell from some wild whim, rather than from his ascetic addiction. When he found out that I was a Czech, he retorted joyfully that he had known personally our Orthodox Bishop Gorazd, [*] and that long ago, on Mount Athos, he had met our Sava Hilendarets, the born near Koutna Hora, Slabor Brauner. He invited me to visit him in his monastery and promised to relate how he had been a leader of Serbian "Haidouts", or as they were called lately, 'Komits". (insurgents)

I actually met him later on. But we did not have an interesting discussion. I asked that we do not mention politics. It was not my field of work. I had come to Macedonia, only to collect impressions and to study the place of this land, in terms of music and art, in the mosaic of Balkan Slavs.

*. Gorazd — from the Cyril and Methodius church in Prague, died together with other Czech patriots after Heidrich's assassination. Author's note.

![]()

99

I knew that I was on a very hot soil, politically speaking. The Macedonians, who had had their Revival in the past century, had aspired towards the creation of new conditions of life, and so had started a struggle against the Turks, who had oppressed them politically and socially, and against the Greeks, who had deprived them of churches and schools. The armed and political struggle against the Turks had followed the struggle on the cultural front, and when in the nineties foreign bands (Greek and Serbian) had appeared besides the Macedonian ones, they had to fight them, as well, since even though the enemy ostensibly was common, the Greek and Serbian bands had their own goals, to fight not the Turks, but the local Macedonian bands, who were believed to be part of the Bulgarian people.

Of course, it was difficult to avoid the political subject altogether. I felt it immediately during my first stroll in Skoplje.

We were in a side street with my son, trying to look into a dreamy, Turkish monastery through the bars on the windows and to glimpse the tall Mohammedan saints.

A man in house clothes was sitting on a bench, beside the house across the street. He told us that it was impossible to enter the monastery. He was a Serbian lawyer. When he found out that we were Czechs, he started, with great interest, a fruitless discussion on Slavdom in general. He had once studied prehistorical times and was interested in the Lugii Serbs, of which he questioned us. He even advanced his own theory, according to which all Slavs were Serbs. His claim was allegedly made good not only by the Polabian Serbs, but also by the Czech people itself, among which the name Serb, as a geographic or family name, was quite common. His theory was also confirmed by the fact, that once, when he had visited Prague, its mayor had been called Dr. Serbin.

"I know that it was a coincidence, but a very significant one", I must say, he added.

I assured him that we, Czechs, would have nothing against it, if it was proved that we were Serbs. We were certain of the original unity of the Slavs and our feelings were pure and void of any fraternal envy.

Then, our willing interpreter put us wise as to where we were, since we had thought all the time that we were in Macedonia. "Skoplje is not in Macedonia. That's what the Bulgarians say. According to them, Macedonia begins north of Skoplje Cherna Gora and Shar, but it actually begins not far from here, to the south. This is still Old

![]()

100

Serbia. The zone with the towns Koumanovo, Tetovo, Gostivar, Kichevo, Ohrid, and of course Skoplje belongs to it."

I could, of course, simply state that King Miliutin had been the first Serbian ruler to conquer the region for a longer period of time, and because of that was called conqueror of Macedonia, but I remained silent. I mention all this, because the fanatical man called the towns that he listed, with the correct term "contested zone", which I must mention in order to protect myself from possible accusations that in my book on Macedonia I am writing of a region which does not belong to Macedonia. But Dr. T. Djordjevich, a Serb, released the second edition of his "Macedonia" in 1926, and even though he excluded the region from Macedonia, he didn't exclude it from his book.

The term "contested zone" originated at the diplomatic talks between Bulgaria and Serbia, when the general terms of the Balkan War were negotiated in 1911. After the victory of the allies, Serbia acknowledged the Bulgarian claim over Macedonia and Bulgaria the Serbian over Old Serbia. They only were not able to agree where the border between the two was to pass. It was exactly those towns that were contested. The Russian Tsar was the one to decide after the war whom the "contested zone" should be given to.

The Tsar never had to decide anything, since as it is known, the Balkan War changed so significantly in its second part that Bulgarian was left alone and exhausted against her former allies and the kind-hearted Rumania, which also ran to their aid with her fresh regiments, ad with a worthy of "praise" courage carried away the crops from Bulgaria's fields, guarded only by old people, women, and children.

The reasons for this twist of events have already been examined in numerous works, with different standpoints, and consequently with different results. But from all of them it is clear that it is Macedonia they are speaking of, and the whole of it at that, and not just the "contested zone". Also, after the battle at Koumanovo, the Serbs, who had taken over Macedonia, had closed all Bulgarian schools immediately and had replaced the Bulgarian priests with Serbian ones.

We, as Slavs, must naturally be interested that Serbia achieved its victory over the exhausted and abandoned Bulgaria with non-Slavic assistance and on the basis of an agreement, which ceded Slavic

![]()

101

territory to a non-Slavic state. I am not about to judge the Serbs' behaviour, but I think that we cannot agree that it befitted a Slavic nation, after it aimed the loss of Slavic land to non-Slavs.

So the result of the war was quite non-Slavic, since Rumania received Bulgarian land in Dobroudja, Thracian Bulgarians remained in Turkey, while Greece got-southern Macedonia with 300 000 Slavs, who were later proclaimed as "Bulgarian speaking Greeks".

The largest part of Macedonia was, of course, allotted to Serbia, but there the Macedonians were not allowed to call themselves Bulgarians and they were officially proclaimed as Serbs.

Bulgaria received only an insignificant portion of Eastern Macedonia, which was further clipped off after the World War. If we can imagine for a moment that the Slavic population of Macedonia, with the exception of an insignificant number of Serbs, who had for centuries waged a struggle for liberation against Greeks and Turks as an integral part of the Bulgarian people, we will understand the feelings with which they accepted such a result, after so many sacrifices. We will also understand the numerous deplorable events of which we occasionally hear, and the many more we never hear of, since even the statements of that real friend of the Slavs, Scouttus Viator (Setton Watson) are hidden, or accepted with disagreement in our country.

One might say that in our country it is a mere continuation of the way that our public has treated Macedonian Slavic branch. Only the reasons then and now are different. The pre-war ignorance of Macedonian conditions is up to a certain point excusable. Travels in Macedonia then were undertaken only at the expense and efforts of separate individuals, to whom the territory had made an impression with its high prices and its insecurity. Only a handful of specialists knew the real state of things, but their voices could hardly creep into our society. In 1909, Dr. L. Niderle won a recognition with his work "The Macedonian Question", whose scientific value was appreciated among all fair-minded people.

The struggle of Macedonian Slavs had not been so simple and easy, as that of the rest of the Balkan Slavs, for whom the simple formula was sufficient: Slavs must liberate himself from Turks, Christians from the Muslims. It was enough that the press opposed the cross to the crescent in the crudest fashion, for which their vocabulary had

![]()

102

been sufficient.

It had been different in Macedonia. First of all her territory, which had belonged to three Turkish provinces had not been a defined geographic, much less even as political concept. But as a national concept it had represented a complex phenomenon. The Slavs had accounted for half the population and the reason for their predominance had been the fact that the other half had consisted of fragments of all the Balkan peoples and that partly, the Slavs had formed the connecting link of the country, while the other half lived scattered in separate town quarters.

From manuscript 128 to 135

The role of a national enemy to the Slavs had been played not by the Turks, but by the Greeks, one of the least numerous elements, but the most dangerous one, since the churches and the schools had been in its hands. It had Hellenized and demoralized.

And finally — the thing that is most delicate in explaining the Macedonian question. The conditions became even more complicated when in 1872 the Turkish Sultan recognized the Bulgarian Exarchate an an independent church. The Bulgarian success aroused a keen political interest in the Serbs towards Macedonia. Its Slavic population was designated as Serbian, even though all scholars, Slavic and non-Slavic, still believe the Macedonian language to be a Bulgarian dialect.

The question, was Macedonia Serbian or Bulgarian, was discussed in some Slavic periodicals, and since Bulgaria lacked such a promoter as the popular Joseh Holecek was for the Serbs, the wide public and the press itself remained without a guide on the Macedonian question.

The insecurity alienated most, with minor exceptions, since they were afraid to touch the subject, or still more, to write something harmful of the Serbs. So, after numerous, bloody struggles, the glorious Illinden uprising began in 1903 (on St. Illiya's day). And our press could not arouse the necessary interest in the brave revolutionaries, even though the three-month long battles stirred Europe so much that a meeting of the three monarchs was called.

Our attitude towards Macedonia, after the World War, remained the same and even deteriorated. Ignorance continued to reign, even though it was admitted that Macedonia was a powder keg, or at least

--------

![]()

103

the key to a union between the Balkan Slavic countries, which would limit the access of foreign elements and influences into the Balkans and the position of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria would become a firm as a rock.

Before the war we used to spell it in Bulgarian-Macedonian - Skopiye.

But the name is neither of Bulgarian, nor of Serbian origin, but a memory of the Illyrians, or (according to Weigand) of the Thracians. Together with the Turkish modifications we find an interesting gama (gamut, V.K.) of forms: Skoupi, Skopiye, Skoplje, Oushkoub. It is the same sound which has been handed down from prehistoric times, from the times of the Dardans, through those of the Bulgarians, Romans, Greek- Byzantines, Normans, Cumans, Serbs, and Turks. Even the excellent name Justiniana Prima, given it in the sixth century, could not suppress the barbaric name and graft the wild tree.

The center of the Illyrian tribes was conquered by the Romans in the second century B.C. From it, they had managed their military affairs in the Balkans and even farther. Later, a destructive earthquake had added to the historical storms, and Justinian I, who was born here, had to build a new city, starting from scratch. As an ardent builder, he had probably done it happily, and the chronicler Prokopios had announced that the city's magnificence had been beyond description. Could it have been just meaningless Byzantine boasting? One can judge for himself from the still preserved, wonderful monument — the twelve kilometers long viaduct, connecting the Skoplje Cherna Gora with Skoplje, which has numerous brick vaults, arousing many mysteries. They were not only of a constructional nature, due to the frequent reconstructions, but of a mathematical one, as well, since their number was so variable, according to the Skoplje "Glasnik Proffesorskog Drouzhestva", which on page 188 stated that "they are over one hundred", but on page 198 they were reduced to merely 55. I, myself, did not dare count them, lest I got a different figure.

The viaduct was the only thing left from the old city, and solely from it one could judge that present Skoplje was built on the same spot. But during the same century another calamity had befallen the city. During the migration of the peoples in the next 400 years, the cm had declined so much, that no one could be sure where it had been

![]()

104

situated.

While stone, prospecting for construction purposes, was going on not long ago, the remains of the firs Roman Skoupi had been uncovered near the villages of Birdovtsi and Zlokouchange, within seven miles of present Skoplje. There, I saw a few open tombs and a part of a basilica. In the past century, the Englishman A.J. Evans had suggested that Skoplje had originally been situated elsewhere, and not at its present location. He had probably reached that conclusion when he had noticed that the troughs and the wells of the Birdovtsi peasants were made of Roman debris, as they were when I was there.

According to the Serbian historian M. Kostich, it was during the reign of the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon (around the year 900) that the city had finally "shone again". By then it had been in its present location, along the banks of Vardar, under the loose, 50 meters high, neogenic rock, where now, in the place of the castle, there were ordinary barracks, called unjustifiably, according to Serbian writers, "Doushan's" castle.

After the fall of Samouil's Bulgarian state in 1018, there came the Greek-Byzantine and the Bulgarian-Assen periods, followed by the Serbian domination, starting with King Miliutin in 1282 and lasting until 1371, when they were defeated by the Turks on the Maritsa river near Chernomen (Vuk Brankovich had only remained as a Turkish vassal by then.

As the Serbian scholars point out with regret, no records of Serbian times have remained. The big, stone bridge, resembling our Karlov's bridge and serving as a foreground scenery to the castle, is also unjustifiably called "Doushan's", (according to Dr. B.S. Jovanovich [*]), since it has been built by the Turks.

Nevertheless, Skoplje had been a memorable place for the Serbs. In 1346, Doushan, who proclaimed himself a Tsar, crowned himself, called his sejms, and published his famous collection of laws there.

The Turkish age had been quite favorable for the city. The number of inhabitants had reached 60 000 (which is its present number). The Turkish traveler Evlia Chelebi was full of admiration. He had found a city of white, paved with stone, and surrounded by a castle wall with 70 towers. Inside, there had been 10 000 houses, 2150 shops, 120 mosques, and 110 water fountains. 1 000 mills had worked in the vicinity.

*. Glasnik Proffesorskog Drouzhestva — V.4 196. Author's note.

![]()

105

All this was destroyed in the fire of 1689, ordered by General Piccolomini, when he was forced to retreat from the city. The incendiary had watched his act from the castle walls. Only the grand, old mosques had been left. They still form the basis and the richness of the present city, insofar as the perverted and false "progressiveness" has not prevailed over reason and taste. They also are its greatest decoration.

The present Skoplje is rapidly expanding and in a typical way, after the changes which have occurred not only in the Balkans, but elsewhere as well, without paying any attention to the cultural or artistic values of the conquered or overcome past. The local buildings, classically beautiful and in proportion with both the climate, tradition and demands, were making way for the rejected, lacking any character Western style. The Middle European, "modern" architecture was being inserted constantly. (In this respect, only Austria had acted otherwise in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and her merit was not diminished by the fact that she had preserved the old style in order to please the Turks).

In Skoplje, as elsewhere, many sins have been committed towards the Holy Ghost. One of the most drastic ones was the tearing down of the magnificent mosque, which together with the old bridge, the river, and the castle had represented a wonderful scene. Now, in the place of the mosque, there is a modern, Renaissance [*], officers' casino, called by the population "The Locomotive". The Serbian writer S, Krakov, in his book "Kroz Yuzhni Serbiyu" sorrowfully lamented the fact that "because of that clumsy building, Bourmali Mosque, perhaps the most beautiful and oldest, from the fifteenth century, had been sacrificed".

Further one he said: "Because of the same reason — to open the view towards the castle — the oak-tree on the other side of the Vardar bridge, which was mentioned in all old chronicles and was also called Doushan's, was cut off. The Turks used to hang our people on it. It would have been the best monument for those martyrs who had died on its branches. Now only the trunk, from which a few branches have grown as a condemnation from the undestroyed century-old power inside it, remains". In order to make the "victory" full, a monument for those fallen in the World War was erected next to it. It was so clumsy that another one like it could hardly be found anywhere else.

*. The author probably had in mind Neo-Renaissance. Translator's note.

![]()

106

Nevertheless, Skoplje's beauty had not been destroyed. That, which the Turks had sown for 500 years, could not be reaped in one. Next to the Turkish quarter, domineering with its red sahat koula (clock tower) and the merchants' streets, whose colourfulness was filled in by brisk Spanish Jews, there were 30 mosques, 20 Turkish monasteries, many baths and bathing pools, marble water fountains, and a large number of old inns, among which was the famous Kourshoumli Inn (Lead Inn), built by Doubrovniks' merchant colony in Eastern style, with numerous domes and arches. It was being prepared for a museum.

The city's attitude towards nature, resolved with such artistic beauty, was also indestructible, although hundreds of trees had failed victims to woodcutters' zeal. They were being cut off on the pretence that in this way the area would be dried up and rid mosquitoes, but the picture did not changed considerably. As we stood on the bridge and looked around, we became certain of it! We were angered, seeing the Turkish plaque in the middle, carved out delicately and beautifully in the marble, was hidden by a number of nonsensical posters that had been posted on it by deluded people. Our eyes were immediately captured by the clear and wide river, in which numerous dyers were immersing and then drying violet scarves and curriers were immersing and then drying violet scarves and curriers were tanning furs in cylinders. After that, our eyes moved along the marvelous mountain peaks, among which Liubotin dominated the Shar mountain to the west, with enough wisdom to preserve an ice cream cap for itself in the heat. A long time passed before we could say farewell to the beautiful scene.

Our nights were especially pleasant. Instead of the daytime din, there was only the ripple and the lapping of the river and the music from the military casino, the cabarets, and the cafes, which intermingled with the gypsies' songs and the crickets' orchestra. On the mountain slopes of the high Vodno, to the south, the lights of the only European tropical institute flickered. It was an institution with the size of a small town, founded with Rockefeller's aid and managed (at the time of our visit) by our compatriot Dr. Noheil. On the roof of the nearby building a movie was being shown and we could discern both the audience and the images on the wall. The hot southern nocturne held us in its grip, from which we were relieved only by the frequent fire alarms.

![]()

107

One of my significant visits was that to the mayor's office, where the very intelligent mayor, Mr. Sapoundjich, received us politely. He was still with fresh impressions from his visit to Prague. He had been to our country to gather some experience and knowledge on the subject of city refuse — how to cope with it and was it expedient to do so. while we drank black coffee he was able to converse with his visitors in pseudo-Rumanian (Tsintsarian), Greek, Albanian, Turkish, and maybe Spanish and Romany. I don't remember any more.

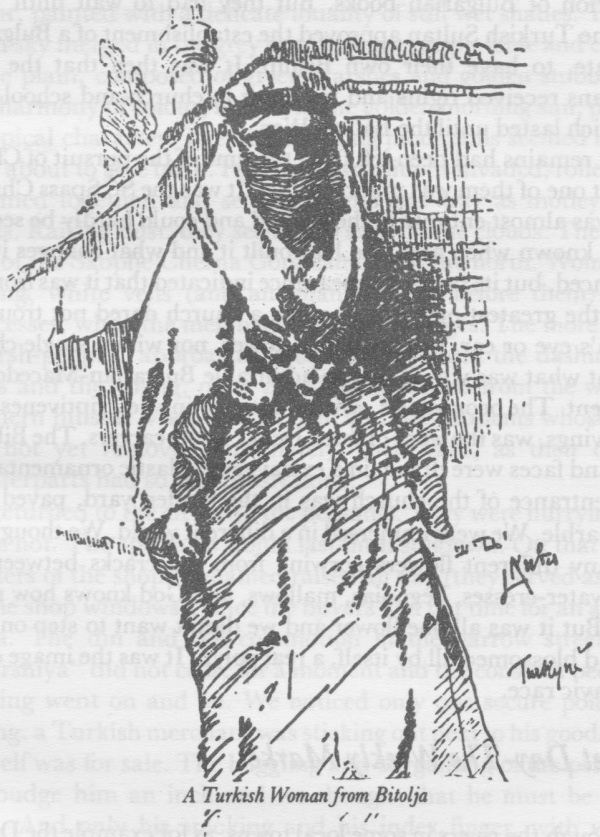

A Turkish Woman from Bitolja

Skoplje, with its inhabitants, represented the Balkan peninsula on a small scale. Before the war the city had 32 000 inhabitants, including the Serb colony. 15 000 were Moslems (Turks and Albanians), 13 000 Macedonian Bulgarians, 1 900 gypsies, 800 Spanish Jews,

![]()

108

450 Wallachs, and 50 Greeks.

The Skoplje Bulgarians had been among the first in Macedonia, in the past century, to manifest a desire towards a life as Slavs. They had started a struggle with the Greeks as their national enemies. As far back as 1833 they drove Greek priests out of the churches and demanded that they be replaced by Bulgarians. For four years rich merchants had collected money to found a Bulgarian school, and with the aid of voluntary contributions had created conditions for the publication of Bulgarian books. But they had to wait until 1872, When the Turkish Sultan approved the establishment of a Bulgarian Exarchate, to have their own Bishop. It was then that the local Bulgarians received rights and freedoms in church and school matters, which lasted until the Balkan War.

Scant remains had been left from the time of the pursuit of Christians, but one of them was unforgettable. It was the St. Spass Church, which was almost entirely in the ground and could hardly be seen. It was not known when and who had built it and what changes it had experienced, but its present appearance indicated that it was from the time of the greatest oppression, when a church dared not trouble a Moslem's eye or ear, neither with a tower, nor with a single chime. And that what was why it was an admirable Bulgarian-Macedonian monument. The iconostasis, with an astonishing descriptiveness and rich carvings, was the work of three Debar wood-carvers. The Biblical scenes and faces were drawn in a extravagant plastic ornamentation.

The entrance of the church was in the hidden yard, paved with white marble. We were immersed in a different world. We thought we saw many different flowers growing from the cracks between the stones-water-cresses, begonias, mallows, and God knows how many others. But it was all one flower and we didn't want to step on it. It grew and blossomed all by itself, a real polyp. It was the image of the local Slavic race.

Even though the rivers in some local towns, as for example the Dragor river in Bitolja or the Bregalnitsa in Stip, take their vacations in the summer and send their fish off on a holiday, and the arches of the bridges and the canal openings yawn tediously, and during market days are amazed by the fact that instead of trout lazy hogs are rooting

![]()

109

about the river beds and the rounded stones are replaced by the slender "stomni" (classical, round water vessels) of the local potters, the market day everywhere in the Balkans is a source of paintings, typical with their fathomlessness and turbulence, always identical, but always enchanting.

Skoplje was transformed into such a kaleidoscope every Tuesday.

The beautiful Skoplje valley must excuse me for the imperfect comparison, if I say that in the morning it resembled a subtle water-colour, painted with a delicate tonality of still wet shades. The blue- green sky merged in the grey mist with the purple-blue and chocolate of the plain, composed of green marshes and golden stubble fields. The harmony of colour, bathed in the golden morning sun, possessed a tropical character. The neighbouring mountains seemed as if they were about to give birth. Peasants' expeditions invaded, rolled about, swarmed together, and set out on the star way as motley dressed corals. Raising dust, they seemed to swim in the clouds. The inhabitants of the Skoplje Cherna Gora came from the north. Women, with waving white veils (and an infants cradle before them) rode as princesses, while the men held the reins as pages. The more sluggish "marsh-people" approached from the east, and the dashing Albanians and the young, puny pseudo-Rumanians from the west. The southern hillside Vodno, or Nerezi, sent the Moslems whose women had not yet removed, fortunately, their veils, as their city-born counterparts had so generously done.

I returned to the city with the peasants. They were hurrying, while I was not. The spectacle would last until sundown. On that day, the shutters of the shops remained raised all day (they served as a shade for the shop windows), since the buyers had not time for an afternoon siesta. The din and the commotion in the narrow streets of the "charshiya" did not cease for a moment and the constant beehive-like buzzing went on and on. We noticed only one secure point in the throng, a Turkish merchant was sticking out next to his goods, as if he himself was for sale. The haggling and bargaining of the peasant did not budge him an inch and we thought that he must be made of wax . .And only his smoking and his index finger, with which he rubbed and picked his nose occasionally, and tried to push it in further than it would go, assured us that he was not.

The Spanish Jews and the Christians, of which the richer amused themselves with an amber rosary, were more adroit. The seriousness

![]()

110

of their profession was backed by some unwritten sayings, like the following, which was said with a doubly insulting politeness: "Respect for everyone, credit to no one".

The skinny and tall dervishes looked even taller in their high hats. They and the imams with the white scarves, wrapped around their bright red fezzes and the white caftans and waving majestically around their wide breeches, were a more peaceful element in the pedestrian traffic, surpassed only by the meandering cattle of all sorts: cows, calves, and goats. During their independent strolls, they hardly looked like the stupid brutes they really were, since they seemed so intelligently bored among the displayed merchandise, as if they were aware of the contempt they aroused because they had no money to buy any of it. In return we, the foreigners, seemed to arouse their interest, because they had no money to buy any of it. In return we, the foreigners, seemed to arouse their interest, because they kept an eye on us, as if trying to guess where we had come from. On the other hand, their smaller friends — pigs, dogs, and chickens — were not troubled by such curiosity. Bent over the deep crevices in the monumental pavement, they were moving slowly but steadily towards the goals they had chosen. They paid attention to no one, not even if someone bumped into them occasionally, as we did.

We were impressed by everything: the people with their costumes and attitudes, the groups engaged in picturesque conversations and haggles, distinguished by their vivacity and their peculiarities. The peasants had brought everything that they might sell and were taking back all that they had bought and all that they hadn't been able to get rid of. It was not by chance that such barters were called by all Slavic peoples "tirgouvanie" — exchanges. The right hand of the unyielding seller would jerk back sharply when he would not agree with the price given him for his merchandise. If the deal had been concluded quietly, the two parties would part wearily, each one of them certain that he had been swindled. If, one the other hand, there had been heated arguments, they would part contentedly, certain that they had done as well as possible.

An enchanting phantasm flashed nearby. We followed it as if we were following a star. It was a peasant, adorned from head to toe with garlic, as if with a wreath of enormous pearls. Such unseen beauty! The shop was an Asian sanctuary, a scene from A Thousand and One Nights. The walls, the ceiling, the floor, everything shone like an opal

![]()

111

covered with pearls that have grown in a garden. The garlic stalactites and garlands rose all around the grocer, who was sittig like a Buddha. He stretched a hand towards the displayed merchandise as Dalai Lama towards an offered sacrifice. The peasant suddenly took off the fabulous robe, and poetry, under the chilling breath of business, was suddenly transformed into prose. He moved off, all at once much poorer, and we did not follow him any more.

We reached the most beautiful part of the "charshiya," the part with the fruits and the vegetables. We saw that the specialised onion shops were not less charming. Nearby there was a shop which seemed to be of blood-red bones, burning in the sun like red flames. They were just ordinary peppers. Whether they were thrown in heaps or hanging from a wall, they were like cut off tongues on St. Nicholas's day, or even better, like real devils (since they were hot like hell).

Pyramids of all sorts of water-melons were arranged as cannon balls in an arsenal. Some of them, like cut in two rounds of beef, with their redness were attracting swarms of flies, which resembled livers, except that they moved. The rolling about fatsos could be identified by their colours and their stripes: musk-melons, cantaloupes, or water-melons. The latter reminded us of an incident that one of our compatriots had had. Not knowing the language well, he had tried to adapt the Czech and the Slovak to the south Slavic. When he was asked if he was married, he had answered, "No, but I plan to do so soon. I have a liubenitsa [*] waiting for me!" His ambitious smile had vanished at once, when he had seen the effect he had achieved.

Money was treated in the same way that the boys treat the butterflies — it was immediately put under the hat and carried over the head all day. And the rumpled pieces of paper looked just like butterflies. When they were many, one could easily understand the saying that "money had stepped on someone's head", and it becomes obvious that southerners are quite rightly called "hot heads", since even in the greatest heat they wear enormous, bushy, fur caps. Furs were worn all year round, and they were masterfully worked out, not only the edging, but the lining as well, especially those of the rich townspeople. Xenophon, in his Anabasi (VII.4), wrote that the Greek soldiers in Thrace had envied the locals for their warm, fur caps

*. Liubenitsa — in Bulgarian a water-melon. The "compatriot" had tried to adopt the Czech word sweet heart to the Bulgarian language. Translator's note.

![]()

112

and coats, I was reminded of the recently deceased Serbian scholar Tsviich, who was greatly troubled by the question, whether there was an Ice Age on the Balkans too, as it was proved for the Italian and Iberian peninsulas. He had managed to find out, as a result from his difficult expeditions in impenetrable mountains. May be it would have sufficed if he had noticed the fashion, which was preserved since those cold days, as Xenophon's statement indicated, and which was a manifestation of real backwardness of the people, which even now, in the heat, were not able to sweat properly.

We were sweating all the time. We decided to end our stroll, so we left the "charshiya" and passed by a smithy, in which an ox was being nailed, and I must say, quite comfortably. They tied up its hoofs, passed a thick beam between its legs, turned it over, and while it was half-lying, half hanging, it could happily watch the passers by while being nailed. It didn't suffer as our cows, which often, weak with pain, hit the blacksmith and the others with their hind parts and sprayed them so much that they had to wipe their faces clean, and not from tears, of course.

We walked around the houses, surrounding the round and wide puddle, called "Lake Ohrid Hotel". It seemed doubtful that it could survive in the heat and was probably artificially maintained for advertising purposes.

A small gypsy boy, knocking a brush against a wooden box, approached us. Should we let him polish our shoes? How many times had we done it today?

"Only from the dust", said the boy, guessing our thoughts (they charged only half the normal fee for that).

"Here we go again," we thought, "soon all our "prakhi" will vanish in your "prakh"!

We smiled at the boy and it smiled back. It smeared shoe cream on the bare foot of its friend and began polishing it with a brush. Wasn't it making fun of the international proverb of the blacksmith's mare and the cobbler's wife? Or maybe it was making fun of us, of our thrift? Maybe it was gallantly trying to tell us that money was not the point, but that just the act, which it adored doing, mattered? It could be. Good for it if it was so! Good for its wit, manifested by an innocent whim, and especially for its idealism! Long live all who enthusiastically perform their vocations! They work with an amazing interest, with an artistic fervour. If one travels in the Balkans, from the north to

![]()

113

the south, he will notice how the shoe-shine boys' class becomes more refined. In the south, they place their profession high and not every shoe is fit to get a shine by their artistic hands. I, myself, saw how a gypsy boy refused, with a contemptuous grimace, to polish a peasant's muddy, rubber sandals, a job which in Serbia would have been done without any disgust by a colleague of his. Of course, he would show the same indifference and apathy if he was polishing a pair of patent leather shoes, while the Macedonian gypsy would caress them gently. He knows what he is doing and why he is doing it: with his own hands he is helping his fatherland shine. It is his privilege and his duty, and from them he draws his self-confidence, with which, as an official, he calls people to his street tribunal with a knock on his box, or with the same signal orders them to change the foot on the box, when one of the shoes is ready.

The Macedonian gypsy was a peculiar creature! Settled permanently, he had preserved all his peculiarities, which could survive the melting pot of his place of permanent settlement. His distinctiveness, not only outer, but inner as well, was especially evident during market day, when his figure could be glimpsed occasionally in the crowd. He could most easily be discerned from the peasant groups.

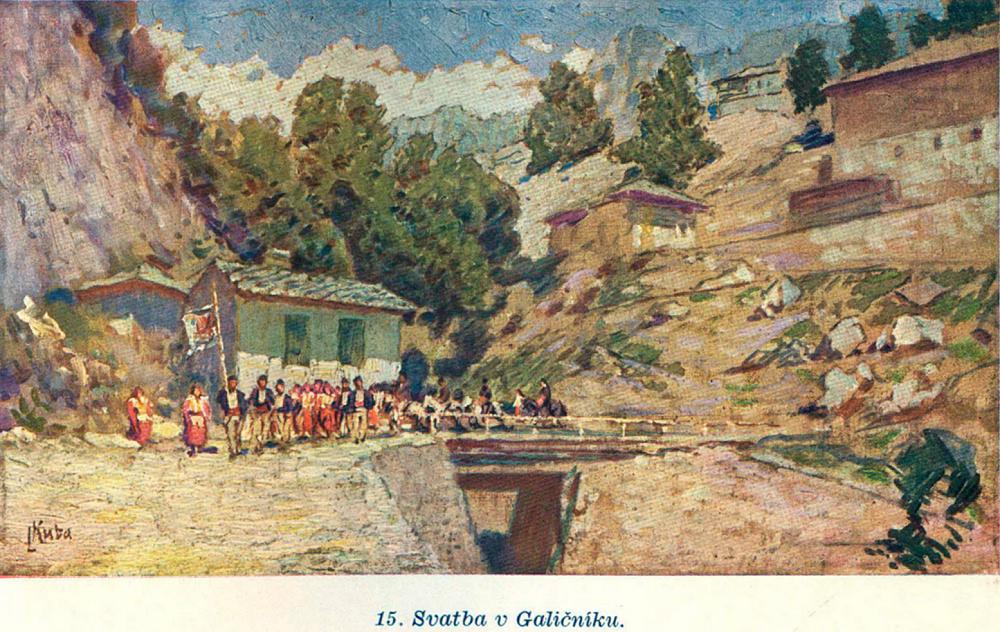

The peasant's figures, with their amazing, majestic costumes with magnificent colours, walked slowly and leisurely, in conformity with their clothing, which with its style picturesqueness, and embroidery was itself ceremonial. The peasants walked with an air of importance, almost sluggishly, as if with each movement they wanted to underline the seriousness, the suffering, and the tragedy of life.

A couple of sun-tanned, ragged gypsies passed by us. Those of them who were going, or coming back, from work walked easily and briskly, and they probably did it because in that way they would have more time to lie down. They looked like carefree sparrows. The father teased the infant, which the mother was holding to her chest. Life seemed to be a game for them.

But it wasn't. On the contrary, they lived surrounded by disregard and earned their bread with hard work for minimal pay. When some time ago, the Skoplje authorities wanted to tear down their quarter and move it to another place, an hour's distance away from the city, the merchants had objected by asking, "Who will perform the heavy work so cheaply?"

The only pleasure in their lives was music, to which they were

![]()

114

addicted. If in any shop a record player was turned on, they would swarm with wide-open eyes and pricked up ears.

One evening, before the cafe where a Czech trio was playing had opened, their teeth and eyes shone so fiercely, that my neighbour, a compatriot of mine, who had just arrived from Czechoslovakia with a head full of dreadful stories of this region, pointed terrified to one of them and said, "That one would finish us off if we met him in a dark alley!"

"That one? That one simply loves music. If you want to learn anything about the local gypsies, just ask our hotel manager, who employs a few old gypsies. They clean the place and he says that he is not afraid to leave them unattended. The gypsies here are honest. They would kill one of their own if they caught him stealing. He has only one inconvenience with them. When he hires them, they always discuss the food — how much bread and cheese they are going to be given and that they should be given no meat. The gypsies here have emigrated from the East in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It is difficult to say what their religion had been. Here, they either profess none or all of them. They are eclectics. They don't care which religion they profess, but they observe all the holidays. They are somewhere between all religions. On the outside, they want to please all, but on the inside are alien to all. You might think that they have not risen high enough to become attached to any of the religions, but it might be just the opposite — they might have risen above all of them. So far, we only know that they remain independent of any of them. In

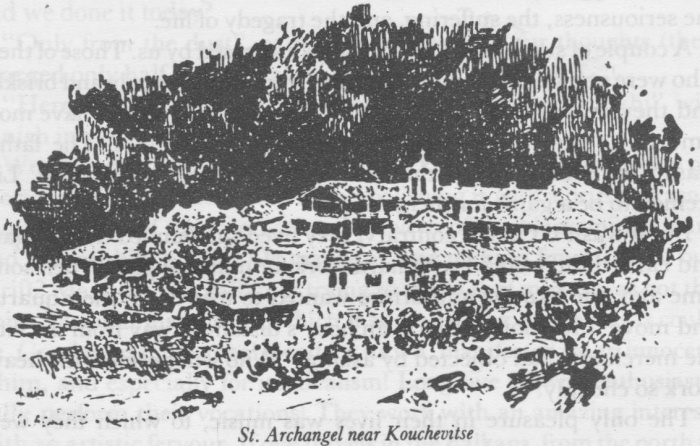

St. Archangel near Kouchevitse

----------

![]()

115

this respect they are superior to the Jews. During the half millennium in which they have lived in the Balkans, astounding changes have occurred, both inner and outer. There has been a great migration of the population from the south to the north when the crescent had begun penetrating here, and afterwards, when the crescent had retreated, in the opposite direction. But nothing has been able to budge the gypsies-history has passed through them as through a fog and left no traces, as a ship leaves no traces in the sea. The great concerns of mankind as a whole are unknown to them and its ideas never seem to touch these gypsies. If all this does not surprise us when it occurs to their compatriots, the nomad gypsies, it should when it does to the local gypsies, who aspire with their work to become members of the society and to be useful to it."

My compatriot, as if he had heard nothing, said, "Refuse! The scrap of mankind!"

"It depends on the point of view. They are an element from a different world, with a different inner life. Nothing is known of their origin, but if you look closer, behind their unattractive appearance, there lies hidden a cultivated elegance, which at appropriate occasions comes to life, like a spark in the ashes. What seems like an atavism and an inclination towards primeval man, is actually a taste for luxury. They seem to be descendants of century-old, noble castes, in whose tradition the animal has not been entirely forgotten. It can be seen in the rags they wear, which are sometimes mended with an astonishing, peculiar taste, but never carelessly. Look at any gypsy woman, old or young, and you will notice how prettily she has stuck a rose in her hair or her bosom and how elegantly she walks. A lady is hidden in each one of them. You can see it in the hotel, when one of them finds a cigarette butt, in the way she will ask you for a light. And you will be further surprised when the old woman nestles in a corner, like a pile of rags, and still, in the elegance of the curved lines of her cigarette smoke, she will continue to be a symbol of poverty and misery. Even old age cannot erase the slenderness of her limbs and cannot bend her spine. This cannot be explained only with preserved sprightliness. The reasons must be much deeper. They don't shun from any work. Not long ago, for example, a gypsy was weaving baskets with astonishing dexterity, in an extraordinary heat, and a boy was helping him. At the same time, both of them had managed to preserve their taste for idleness in exactly the same degree, and at a

![]()

116

certain moment they both devoted themselves to a voluptuous languor. Just imagine any of their women fashionably dressed and you will agree that she may appear among the most elegant company and will never be felt as an outsider, but as an integral part of it. And take notice, some evening, of a gypsy orchestra in the square, whose members are dressed in Western clothes. You will be amazed to find out that each one of them looks like an European commercial counselor or a relative of his. You must understand that the whole race lacks nothing but prospereity, in order to appear as caste of cultivated lovers of pleasure. As for now, they have only music, which raises their spirits as opium. For some of them music is a living, while others carry (alone!) whole beams padded with a sack of rags, which, while they are resting, serves as a pillow. In the evenings, they amuse themselves with songs, with zourlas, and with drums, for which sometimes and earthenware pot or a wooden box will suffice, since even on them they can expertly bring out unusual rhythms, which are heritage of the Orient".

My lecture was making my compatriot weary. I stopped talking, since there was no use in wasting my words. I did not tell him to visit the gypsy quarter and see the poor, filigreed huts, which were actually made of clay and sheet iron (or of anything else) and resembled May-bugs, but some of them were exquisitely decorated with flowers, most often with sunflowers. I did not tell him of the gypsy dance, with which a child of four had hurried along, while trying to wrap a piece of new pink cloth around itself, with the comic sincerity of an old coquette. It looked at everyone it met, in order to receive recognition and admiration. I did not tell him how the fast rhythm had allured outside a sick girl, who was placed on a rug, with her head raised, so that she could participate in the wild dancing at least with her eyes. Even the Christian city youths could not resist to participate in the chain dance, while their whole families were indignant. The youths were finally pulled out, after a lengthy scuffle, from the circumstances which had desecrated them. I mentioned nothing of the old gypsy woman, which slept on the floor in our corridor and each morning shared her breakfast with her soldier son, who came to see her early in the morning. She was concerned about my son's illness. He could take only tea for a week and she brought him a cup each morning. Once she said, "Today I dreamt that your wife had come to make a cup of tea for your son." She had dreamt it on the hard tiles in the corridor.

![]()

117

I had not started a lengthy discussion with her that day. I had no time since it was market day.

St. Archangel's Patron Saint's Day

It was observed in the end of July in Kouchevitse, three hours to the north of Skoplje.

But just the same (i.e. as magnificent) was St. Illiya's patron saint's day, two hours further to the west.

The differences in the patron saints' days, which were observed on their patrons' days, just as in our country, arose only from the fact that some churches had monasteries and some didn't. The monastery ones were more beautiful.

The monastery — a beginning, a sum, and an end of Medieval wisdom — had struck roots among the Balkan Slavs as well. The Bulgarian, and after them even more the Serbian rulers, had zealously endowed them with a great number of villages and other property. And the royal decrees were valuable historical sources.

The people also gave them many gifts. An old man had told me in Prillep that the Treskavets monastrey, which had possessed until not long ago over fifty villages, had had a shop in the center of the town, where all sorts of gifts had been brought (wheat, lambs, etc.) as offerings for curing the wife or the children of the donor. Everything which the two "epitrofs" (honorary citizens) had collected and written down had been handed over to the monastery on Sunday.

All this had almost vanished now, even though the ordinary people were still devoted to the monastery. In Treskavets, during our stay, two young men were serving as shepherds without being paid, in gratitude to God for being cured. Their mothers had given them to the monastery.

During the Patron saint's day, the monastery attracted people from the whole area. They came from towns and villages, on foot and by carriage. The Moslems came either as musicians, to earn some money, or if they were sick, to be cured by the saint in which they also believed.

By nightfall, the monastery was under siege. Whole families arrived with their bed covers, rugs, and food, on foot, on horseback, or by carts. They occupied the spacious rooms and wide balconies, and

![]()

118

even the lawns, since the nights were warm. Those that arrived riding horses or donkeys, whether men or women, took off the saddles and used them instead of pillows. When on such a day, on a hot afternoon, we were cooling a watermelon in the stream below St. Petka in Ohrid, in order to quench our thirst, everywhere around us we could see women dressed in white, with waving scarves, sick people on horses, gypsies with music, pastry sellers with loaded donkeys, street vendors, city ladies with their lovers, and honourable matrons with fat daddies. The ill and suffering had come to pray and the healthy and young to have some fun.

The big crowds gathered on the patron saint's day, of course. Monks came to lend a hand (since the monasteries often had only one monk), taxies hurried and the people had to make way for them. Everything was jammed — the church, the yard, and the area around the monastery. The loud, deafening din around the monastery replaced the silence which had reigned for a whole year. Everything merged in a unified noise, like that of a waterfall. Numerous candles were quickly sold inside. At the entrance of the church, the priest held out an icon for the visitors to kiss, in one of his hands, and sprinkled them with holy water and blessed them with the other. A large table in front of him collected all sorts of bills and coins. He could hardly withstand the flood (the priest of course; the dish on the table was large enough). He threw an irate glance at the boy, which possessed enough religious interest to kiss his hand and to allow to be sprinkled, but lacked the necessary resources to pay for it. Innocent deception! The people were very honest. This was proved by the plates containing money, which were left without supervision.

We had great difficulty in elbowing our way into the church, and once inside, we could hardly stand the stuffiness. The scene was moving and wonderful, with the people, the priests, and the church. The stylishness of the costumes was increased by the impact of the humble air of the figures. Everyone pressed towards the monks with the small rolls. Half of each roll was returned after being consecrated, while the other half vanished below the desk. It was true that the priests did everything as automatic machines, but still they were so grand while doing it, because at that moment they were super-human martyrs, and martydom always makes one beautiful. They were tired and exhausted. Their wavy hair hanged down from their heads and merged with their arms, just as Jesus's, absorbing the sweat, running

![]()

119

down their temples, faces and noses, with a hard bronze luster, the same that Donatello's John the Baptist captivates us with: Behind them, the icons, arranged on the iconostasis according to their height, seemed to be alive with their colours. At that moment the priests seemed to be transformed into the Deity itself. They looked as if they had come out of the icons, with the serious faces of martyrs and prophets, and the men and women saints, above who, on the arch, were the Holy Evangelists with Jesus Pantocrat. The whole, old building was imbibed by secrets. Its century-old architecture sounded ceremonially, like an organ. The tones seemed to collect the voices from the different ages, always praising God. The columns and the arches were in synchronism with the common prayer of the generations and the centuries, since they were not the product of one moment, but a sum of aspirations, which have captured time, flowing past as a river. The individual was drowned in the current, but the common effort remained. Its author was called tradition, which meant the common soul of a number of generations. Its grandeur was in the discipline of the masses (for whom the separate individual's death meant nothing) and certainly not in the chance whim of the artist. The great artist was nothing but an attainment of the peak of all that had come before him. From all sides we felt great commands, reaching beyond the boundaries of human life. The command rose above everything, above the murals and the architecture and subjected the total impression of the marching army of the generations.

The monks and the children outside were much better off than those inside. They ran to and fro, inspecting the cauldrons with the meat soup, which was being prepared for all the guests. They were also sweating, but still, it was far more pleasant to carry around "monastery" brandy, to divide servings and to command a big meal.

We would have asked them a few questions with great pleasure, but we were afraid that we might disturb or distract them. That was why we stopped the priest with the wide purple belt, who was a guest from the town and was walking around carefree. We presented ourselves and showed him our certificate, a letter of recommendation from His Holiness The Belgrade Patriarch. But alas! The priest read the letter without it having any effect on him and returned it with some unexpected words. We were suddenly reminded that the autocephalousity (or should I call it capricious obstinacy) of the local church reached way down into its roots. They had respect for no one. It was a rare

![]()

120

trait of local democracy, which was typically South-Slavic.

The priests' and monks' class was the same mosaic of human characters that one found anywhere. The decoration of their heads had only an outside effect, but it did not touch the inner self, the moral essence of its carrier.

Another priest happily took us around the church, which had more or less emptied in the meantime. He showed and explained that which interests us, as, for example, the lives and the fates of the saints drawn on the walls. For St. Dimitar, he noted that he was sometimes drawn with a dog's head, which he once really had, as a punishment for being too gallant with the Virgin Mary while boating with her.

We thanked the gay, old man and vanished in the turbulent sea of people, who after serving God, had now become devoted to themselves and to the earthly pleasures. They whirled around the lawn. The bagpipers were blowing their bagpipes and the gypsies were beating their drums. Their "zourlas" pierced the ears and the air, groups of peasants were singing old songs, and townspeople were playing guitars or tormenting breathless harmonicas in the yard, the balconies, or the rooms.

In one of the rooms, a gypsy was standing so comfortably near the door that everyone who left had to stick a metal dinar on his forehead and make way for the next person. The dinar quickly rolled into the musician's lap.

This way of paying fees was only a modification of the one that we had already become acquainted with in Oktis, a village beyond Strouga, on the Albanian border (where we had gone to see a recently discovered mosaic of a Roman bath).

The old women there went from saint to saint, all painted on the iconostasis, and to those who had helped cure them or fulfill their aspirations, they not only read a prayer, but also spit on a dinar bill and stuck it on the saint's face. Some of them were literally blinded by money. The gypsy, of course, was paid after he had played, while the saint, like a lawyer, was paid beforehand.

We merged with the amicable people and soon had to answer all sorts of questions. The most important one was, were we Orthodox? "No".

"Then what is your religion?"

"Mostly Catholic."

"Do you pay a lot of money to the priests?"

![]()

121

"Most of them have fixed incomes."

"We have to pay them for everything separately. And the fees are always changing. Before the war it was like this: five times a year the priest came to my house to bless it with holy water and each time I gave him 20 groshes. [*] When I die I will again have to pay 20 groshes. When he christened me he took 10 groshes."

The arithmetic was correct, since it made it easier for one to enter life and more difficult to leave it. "It's correct," I said, "that it's cheaper to be born than to die, but why on earth does getting married cost the same? Or may be it's all the same to you?"

"Not to us, only to the priest."

"I also, think so. Why, we get married from goodwill and die only because we have to die."

"Both are necessary, both!"

My interlocutor started greeting, hugging, and kissing the newly arrived. The same scene had been repeated many times and it seemed to be one of the basic reasons for the pilgrimage in this holy place. Friends and relatives saw each other, exchanged questions and answers, both superficial and serious ones: "How are you?", "Ail the bread that I own is in me, all the clothes that I own are on me." Strangers became friends. An old granny asked a woman with a boy, who was sitting next to her sadly, as a widow, "Do you have a husband?"

"Yes I do."

"You're rich! And who is this?"

"My son."

"God bless him!"

The words and sentences seemed to be carved out of stone.

The conversations, and the people themselves, were possessed with grandeur. And their clothes as well.

The granny went on, "I also had a husband once. From that time, since God is above me, my face has been touched neither by water, nor by soap, nor by any man's hand."

We looked down at the valley, below the monastery, from the window. On the green meadows, surrounded by green slopes casting violet shadows, white, moving ornaments, fleckered with red, were folding and swelling out all the time. The youth, both boys and girls, but each sex separately, had joined hands in a chain, stirred by the

*. A grosh = 40 pary; 100 pary = 1 dinar. Author's note.

![]()

122

music from the bagpipes and the flutes. Everything had a hard, strong shape, just like the cuts of the shirts, trousers, and sleeveless dresses. Everything was century-old, even though the centuries and the ages were represented by blossoming youth. It was just a bud on the millennia-old, self-grown trunk.

We went down to them. The picture lost the charm of the bird's eye view, but was still possessed by a spell. St. Illiya or St. Archangel watched all this affectionately and smiled, from the dense forests and rocky slopes of Cherna Gora. And why not, all this occured only once a year!

On the one hand, it was a 1500 meters high, bare ridge, which was the divide between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, on the other hand, it was eleven villages along the southern slopes, called in the order in which they come: Choucher, Gorniani, Baniani, Glouvo, Brazda, Myrkovtsi, Kouchefitse, Liubantsi, Pobouzhye, Brodets, and Liuboten.

In all the villages, except the last, an Albanian one, the inhabitants intrigued us with their original, Slavic wholeness, and the specificity of the people and their costume, differing from the rest of Macedonia. They appeared like a magnificent phantasm one after the other. They held us spell bound with their whiteness and their grandeur, and aroused in us a great wish to visit the region. We only asked ourselves instinctively, while looking northwards, towards the bare mountain slopes, in which the Black Foresters [*] lived: why were they called so? Why was their native land called Cherna Gora (during Turkish times Karadag) ?

There was no answer to our question.

Of course, the present bareness of Cherna Gora did not imply that it has always been such. All mountain regions, which had been near the antique Mediterranean culture had suffered so. It had destroyed the trees all the way from Asia Minor to Dalmatia. On the Balkans themselves, its contact had outlined clearly the old forests. If such was the case, then the name Cherna Gora would be a witness to the very old age of the pre-Slavic tribes. Another mystery was why the name

*. Cherna Gora — the Bulgarian for Black Forest. Translator's note.

![]()

123

Cherna Gora referred only to these few villages and not to the inhabitants of the northern slopes, who were mostly Albanians, and who, according to pre-war concepts, had belonged to Old Serbia. Of course, the population there was quite different. The factory owner, Mr. Salvaro from Ouroshevats, who had been born in Dalmatia and had been a Czech student, had sent me interesting data on them. According to him, these Albanians were ancient Dalmatian emigrants. While Mohammedanism was predominant among them (it was a frequent phenomenon among the Old Serbia Albanians), the Catholic faith had also been popular. He had spoken to a priest there, and to his surprise had learnt that some Moslem women had sometimes secretly brought their children, asking him (with a promise to keep secrecy) to christen them. Obviously, under the Moslem veil, the former Catholicism was still smoldering.

And so the northern Cherna Gora slopes were the complete opposite to the southern ones, where the inhabitants had not only preserved their faith and their nationality, but displayed frankness, courage, and proud self-consciousness, as well. From time immemorial they had been able to look down upon the inhabitants of the Skoplje valley. They not only lived, but also stood higher than them. Sociaffy, of course.

While in the lowlands the peasants lived in poor huts, dependent on the landowners, working as employed farmhands, as landless, enslaved rayah, owning neither their souls, nor their bodies, the Black Foresters had always been free, independent proprietors of the monastery, and later of the vakuf [*] lands.

From the back, their villages were surrounded by the marble background of the mountains, and from the front, by the deep, green colour of their gardens and meadows. They were like small towns. The one storeyed, semi-stone buildings were like small palaces, the men and women were like farmers-noblemen. If one chanced to meet a caravan, he could see how the women rode as princesses, and when they had before them and infant's cradle, the husband gallantly led the horse.

As the villages' location indicated, the first occupation of its inhabitants had been shepherdry, which was still maintained. The pastures still existed above the village. Below it were the gardens, the fields, and the vineyards. Whoever had been left without any land had

*. Vakuf — a Turkish church a estate endowed in the memory of someone deceased. Translator's note.

![]()

124

gone abroad to seek work, as a day-labourer or a wood-cutter, or as a craftsman-a baker or a stove expert. Only from Kichevitse and Myrkovtsi no one had had to leave.

As the farms of the industrious and lucky peasants had increased, so had the arable land, which at the beginning had been marked out with a red cord, tied from one tree to the other, until the cords had finally become overgrown with hedges (as in England). Fruit trees were grown here, but the people took care of the others as well. We were passing through a real park in this enchanting country! In the fields there was wheat, barley, rye, oats, corn, hemp, and tobacco; in the gardens lettuce, cabbage, onions, beans, potatoes, pumpkins, egg-plant, and peppers; on the trees pears, apples, plums, walnuts, almonds, apricots, and peaches.

The mountain slopes supplied each village with a stream, which carried the name of the village: Baniani, Kouchevitse, etc. Water from here was led as far as Skoplje, to the Moustapha Pasha Mosque and the Kourshoumli Inn.

Each village, seen from a distance, looked as if it was the seat of a boyar. The houses stretched out high in the narrow streets, their eaves covered with Turkish tiles and touching, and in the open attics one could glimpse the white figures of the beautifully dressed women. But we found no castles or palaces here. There were no masters' seats, but they belonged to the master of the universe. There wasn't, as there never had been, a village without a church. The churches were century-old. The number of scattered ruins was unknown. The charm of the region was increased by the monasteries, hidden mysteriously in the deep mountain slopes. Each village (plus a church) had its own monastery.

The churches, as the houses, were worn out, but it didn't disturb us. It helped us to strengthen our impressions. We felt the breath of nobleness, without which the numerous shrines could not have been created. Ancient culture breathed from everything.

For the specialists, the old shrines are inexhaustible sources for research. The westernmost, St. Nikita from Choucher (with an old school), built solidly from brick, in Greek style, on the model of the Miliutin Hilendar Church, The St. Bogoroditsa in Kouchevitse, and especially the magnificent St. Archangel, hidden deep in the mountains , was full of mural paintings from the floor to the ceiling. Together with the Pobouzhi monastery, they had survived the turbulent

![]()

125

times without being damaged, while the famous St. Nikita church in Liuboten had suffered most. St. Illiya (in the mountains like our Karlstein [*]) was actually a cave in the rocks. Further inside the valley were the ruins of St. Spassitel and Blagoveshteniye, in which unfortunately we could not see everything. The churches were generally of the second Serbian, building period (the end of the Milutins'). They were built around 1330 (may be St. Archangel was even from the beginning of the Turkish age), when the construction of Christian churches had still been legal. The brick arcades refreshed the outward appearance of the classical buildings, They were not presented in commemoration of someone deceased. The sign on the Liuboten church mentioned specifically the founder "Mrs. Danitsa". This confirmed our anticipation that the region had stood well with the local nobility, who had obviously been advanced culturally.

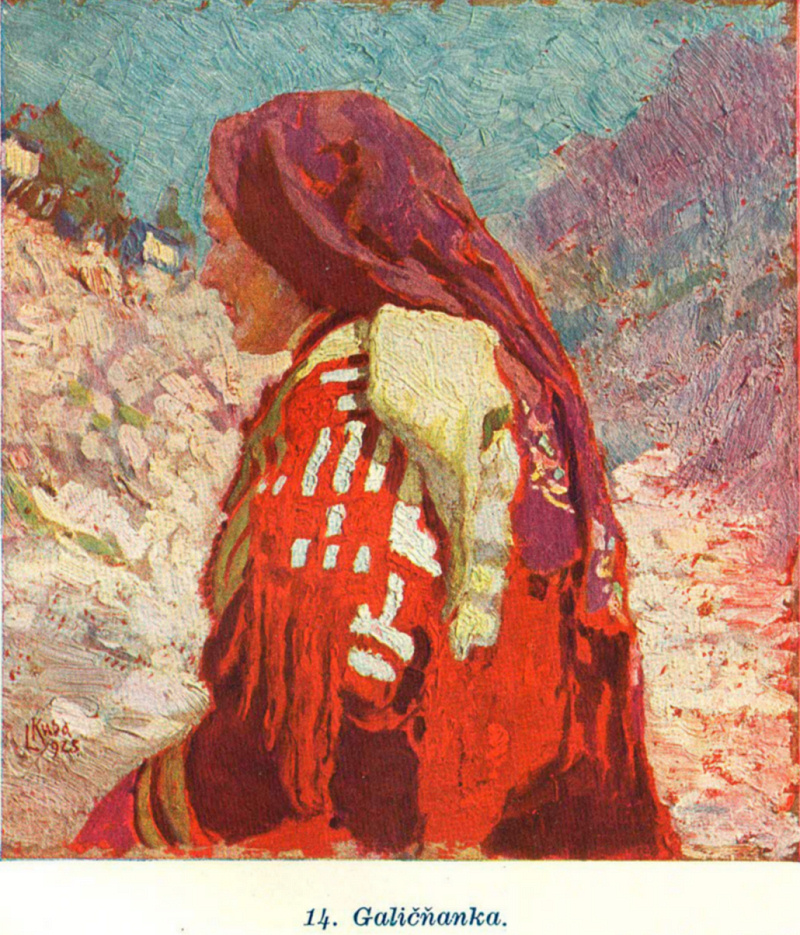

We felt that the costumes, with their beauty, their style, and their spirit were a reflection of those times, even though it was evident that they were mostly home-made. They were of pure wool or hemp cloth. Such had been the original Slavic costume without foreign influences, Greek-Byzantine or Turkish, so predominant in the Balkans. They had no sleeveless jackets, woolen caftans, or padded jackets, no arch-like cuts or fantastic oriental decorations. Not a trace of the endless, complicated spirals, with which the fine broadcloth was embroidered, could be found. The men wore cloth trousers and simple shirts with tassels, tightened up with wide, almost to the armpits, red belts, richly and artistically decorated with white thread. Added to them were the fur caps and the sleeveless, woolen, outer garments, and that was all. They reminded one of the Bulgarian "Shopp," the Herzegovina mountaineer, the Bosnia "Rham," or the Croatian "Lik."

The white colour was predominant among the women, as well. It was matched with their red aprons and the beautiful, embroidered in brown and blue, wide sleeves of their shirts. On their breasts, the coloured threads formed rich figures, but their clothing was otherwise impressively simple. The black, pleated tassles on their backs were splendid. Their faces, with the big, waving veils, were wrapped in white, in a special, typical way. A coloured, variegated, beautiful belt embraced the head from the chin to the crown. The whole face shone as a red triangle. The scarf had to hide the mouth almost to the nose, a

*. Karlstein — a castle near Prague, built in the fourteenth century by Charles IV. Translator's note.

![]()

126

proof that the clothing had had to be such, as to allow the whole face easily to be hidden when necessary. But occasionally, one could see a beautiful woman, whose beauty was marred by a black stain on her forehead or temple. These black stains were drawn by gypsy women in order to "scare away" diseases.

Whenever people weaved a cloth from their shorn wool or from their hemp, they cut out and sewed themselves a shirt or an outer garment and embroidered it in such a way that it had to be fully impressive. And if all had been done according to tradition and the century-old habits, which meant an improvement of the shapes and the models in accordance with the genius of the talented, self-learned individuals, the result could only be a grand, original art, the more so that it would begin developing from early childhood. From the age of eight, the girls would sit together all winter long, preparing their dowries. Their artistic activities would be accompanied by songs, i.e. by music and poetry. The meager rooms in which all this was done, were the people's art academies. Their members could also be divided into classes. The first one consisted of the creative talents, which within the limits of tradition created new forms. The second one imitated it deftly and the third one tried with hard work to keep up with the second.

We were curious about everything and everyone was curious about us.

"Where are you from?" a peasant asked us.

"From Czechoslovakia, from Prague. We are Czechs."

We had told him a lot, and at the same time nothing. Our answer simply contained no information whatever for him. I explained, "Before the War we were under Austria, as you were under Turkey. After the War we gained independent."

"Who is your king?"

"We are a republic."

He contemplated for a while and then asked with some doubt, "The republic is better, isn't it?"

The- question was delicate, especially in these places. Had I to explain that for us it was the only possible form of government? Wouldn't I be in trouble if I did so?

"During Austrian time", I said, "we had a monarchy and now we have been a republic for seven years. I can only say the following: the rich still own everything as before. He who had been a vagabond had remained one, and probably it is the latter who have changed most."

-----

![]()

127

In the Land of the Monasteries

On the advice of our compatriot Dr. Noheil, our first outing from Skoplje was to the Matka monastery.

It lay three quarters of an hour to the southwest by car. The road passed through the Skoplje valley, along the Vardar river, and after the Sarai bridge turned south towards the mouth of the Treska river, which flowed opposite us in a deep rocky gorge. The Bluish Mountains, which formed an excellent background to the lonely, slender mosque, around whose pale, sad face we drove, formed part of the foundations of the monastery, suspended in the end of the gorge on a steep slope, overgrown with fig-trees, mullberry trees, vines, and all sorts of greenery. Such was the Matka monastery!

The car passed through an Albanian village, jumped like a goat over all the obstacles that lay in its way and stopped before the huge, dark gorge, the walls of which were touched by the water, since there were no banks. The precipice resembled a stone grave! For many it had really become a grave. An Englishwoman had once gone down the narrow goat track, since there were no other roads, and had never come back. The recess was luring with its treasures and old churches, but it could be reached only by the river and one might not always have a boat handy. The Prague Byzantologist N.L. Okounyev had tried to reach it through the hill on the other side, but had soon been exhausted and forced to slide down the loose slope. By doing so, he had scared hundreds of eagles from the numerous holes on the opposite slope. They had circled above him with such noisy squeals that he had soon ceased to enjoy all of it. Otherwise, in the constant silence of a half a millennium long dream, three saints stood firmly: St. Nichola, on the other side of the river, and St. Nedelya and St. Andrey on this one. Further on to the east, at a height of 1100 meters stood St. Bogoroditsa, and three hours to the south St. Dimitar, known by the name Marko's monastery (because of the untrue accounts that Krali Marko had built it). It was an important source of information on the history of art.

Saint Pantheleimon, in the village of Nerezi, in the Vodno mountain, also belonged to the Skoplje group. We passed by it, but could not see the monastery because of the dense chestnut trees. It was the ancestor of the rest because it was 200 years older. According to the

![]()

128

preserved sign, it was built in 1164 by the Greek Comnenus and had been dedicated to the doctor St. Pantheleimon. Inside it, there were images of other saints-"doctors", and since many curative springs were located near the village (where the local Turkish women went to bathe) it was obvious that the names — the Slavic Vodno and the Greek Neresi, which were synonyms, were not accidental and that the place really possessed its medicinal past.

All that, together with the gigantic natural scenery, presented a memorable view. We glanced to the north, towards the Skoplje Cherna Gora, also occupied by many shrines and monasteries, and we suddenly understood that the Skoplje valley was surrounded by two rows of fortifications. They were not military fortifications but spiritual ones.

The temple is built as a place of prayer, but is actually something much more. Man, while creating temples, had wanted to express two things — obedience and soaring, to admit his weakness and to manifest his yearning for power. He has achieved the harmony of beauty, which is contained in the unity and struggle of the opposites. With such ecstasy, man has created the greatest and most thorough works of art.

In his creativity, he has been stimulated by the great wish to explain to himself the mystery of life. From his birth to his death he has always sought the answer. Emptiness, both physical (loneliness) and spiritual (Ignorance) is unbearable to the soul. It can never be content with it. Irritated by the impervious veil, which does not give it the answer, incapable or. rationalizing its own image, the soul makes up another, a personification of power and perfection. It is the positive image of its shortcomings; the positive of its negative is incarnated in it. As the French philosopher said: "Semblable a l'idée de moi-même, celle de dieu est née produite avec moi, des lors j'ai été crée"- just as my idea of myself, my idea of God was created with my birth.

All religions and all churches have always had one goal to unite the human with the eternal, the earthly with the heavenly — a difficult and remote task. The human life is too short for its fulfillment and nothing is left to the churches, except to feign their heavenly origin. While offering themselves mankind as intermediaries between this world and the other one, they raise one hand upwards, pointing to the sky, and holdout the other one for the mortal and the sinking. With

![]()

129

the right one they threaten, reminding of God's commands, with the left one they shoothe, appease, console, and lead. They preach justice and punishment and at the same time must promise compassion and remission, since nothing is left to them but to build a bridge between the two poles, a bridge which leads to God. via the angels, the saints, the blessed, the bishops, the priests, the presbyters, and all the way down to the common sinner. It is a transition towards remission and compassion, which mean relief and concession.

Without them man cannot exist, and the Church knows it. In his life and his work. Protestantism offers relief with its rites and formalities. Catholicism, severe in its rituals and in the interdict on marriage by its clergy, is clement in life. The Koran compels its believers to "bow" five times day, which makes 1825 exercises a year, but together with the compulsory washing, it is nothing but a physical health activity, which in its essence is extremely necessary. The Israelites' religion merges with the tribal and earthly life and leads to

The Horse on the Meadow near the Treskavets Rocks

![]()

130

a non-distinguishment of either. The Orthodox man attaches God's Ten Commandments to his forehead and reads his prayers wherever and whenever he finds suitable, as in the church he may speak to anyone on any subject. In such a way, the distinction between his church and the street disappears completely.

Wherever the Church has tried to preserve its loftiness, without managing to adjust itself properly to life, peoples have declined and vanished. And vice versa, the fuller the church's contact with the earth, the stronger it is.

It must allow its magnificent panoply to trail in the earthly dust and its great concern must be not wear out its clothes excessively.

And it is in the mastery of the trailing of the panoply that the Orthodox Church is the greatest expert.

A Serbian acquaintance of mine once told me, "We believe in nothing, we don't respect our priests, but we love our church." Richer in rituals than the Catholic Church and secure in its picturesque impact, it can afford to be freer and more unrestricted. The constant intrusion in the peoples' lives and the greater intimacy, which it can permit itself with them, makes them even more dependent. The priest's standing, both in the church and outside it, allows him to behave without ceremony, not being afraid to lose any of his seriousness. He can behave naturally with the others and indulge in gaiety in his family and in the pub. He can, as I once saw, walk around at three A.M. with a cigarette in his hand, with merry wedding guests. But his Jong hair and beard, his grand panoply and tall kamelaukion can quickly give him back his dignified appearance, his figure of a saint, or even of Christ himself, when it is necessary. Five times a year he visits each home to bless it with holy water. He takes part in family occasions; in the church he constantly performs services; he dedicates loafs of bread and and Easter cakes to be taken to the cemetery on the third and fortieth day after the funeral (wine and brandy is also brought on such occasions); he blesses the crops; he chases away illnesses, and does many other things, with which he not only promotes close relationship, but also ensures observance of the church commandments at home, mainly the keeping of lent. Under such circumstances, it is riot necessary for anyone to care about church attendance. The priest does not depend on it, except for patron saints' days or christenings. Once, in Tsetina, before my eyes, the sexton expelled a boy from the church, beating him with his hat and shouting,

![]()

131

"You have no business here!" (It occurred on a Sunday during a liturgy). In Smilevo, I wondered that there were only married women in the church, but I later learned that this was done elsewhere, as well. I was told that an unmarried girl should attend church service only three times a year, as an exception: on Palm Sunday, on Easter, and during the Three-day Lent.

In the Orthodox church all was possible. The old church had an effect on the people not only with its architecture and its mural paintings, but also with the solemnity of the moment. The mysterious shadows and bright lights, the rich iconostases and the numerous saints on the walls drove the people to an ecstasy. In the holy gates of the altar, the golden vestment with the priest's head, whose white hair

A Peasant from Dabnitsa

![]()

132

shone as silver, seemed to emerge from the waves. He only lacked an eagle, in order to appear as a saint, or even The Father. The puffs from the icon-lamp provided a heavenly background and the magic of the scene had an effect even on us, the foreigners, the infidels. But such supernatural phenomena did not prevent the priest even to make jokes sometimes, on weddings or on christenings. And we were very pleased, when with a cheerful face he offered us some of the "kolyevo" (boiled wheat with sugar), which he had blessed and had begun offering to everyone. He could come down from his pedestal of greatness at any time, without being afraid that someone behind his back might take it away. He was not vexed by the women who gossiped during the service, or held crying infants in their arms, or by the boy who was trying out his new mouth-organ in a corner. Only in St. Nedelya, in Bitolja were the rules stricter, judging from the sign inside the church: "No Smoking". The rituals were preferred to the sermons. That was why news of a wedding was always happily received. Sometimes, it was announced that such and such a girl was poor, that she had no dowry and begged for contributions. Sometimes, even, it was specifically mentioned what exactly was necessary: linen, clothing, or furniture.