PART I. MEDITERRANEAN AND ORIENT

Egypt 6

Eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Mesopotamia 7

Persia 8

India 11

The Semitic Peoples of Mesopotamia, Syria and Arabia 12

Celts, Scythians and their Successors 17

East and West 19II. The Liturgical Background of the Early Byzantine Church 23

ALEXANDER THE GREAT

Chapter I. The Legacy of Alexander

More than two thousand years have elapsed since the existence of a sovereign state of Macedonia. Yet, despite a more than ample share of political vicissitudes, some kind of Macedonian identity has persisted within geographical boundaries that have changed little since the time of Philip of Macedon. Such continuity is the more extraordinary since this Macedonian identity has had neither a firm political nor a uni-national basis. Like the Byzantine Empire on a larger scale, throughout its history it has been a synthesis, sometimes easy but often antagonistic, of widely opposed cultures — in the case of Macedonia of the Greek urban and coastal region and the Slav, or, in earlier times, Thraco-Illyrian hinterland.

On a physical map of the Balkans Macedonia appears as the land area bounded in the south by the Aegean Sea and the Olympus and Pindus ranges, by the Pindus and Albanian mountains to the west, northwards by a more variable line traversing the mountains beyond Skopje, where it merges into country originally inhabited by a powerful Illyrian group known as the Dardanians and which later became the Early Byzantine province of Dardania, and to the east by the western ends of the Balkan (or Haemus) and Rhodope ranges of Bulgaria. It also includes the island of Thasos. For the greater part mountainous, the most populous district has always been the city and plain of Thessalonica facing the Gulf of Thermal in the Aegean Sea. Into this flows the Aliakmon river from the west and the Vardar (Axios) from the north.

Following courses roughly parallel to the Vardar, the Strymon (Struma) and the Nestos reach the Aegean east of the mountainous, triple-pronged peninsula of Chalcidice. Macedonia’s other important river is the Cmi Drim, flowing north from Lake Ohrid through

wild and mountainous country to carve a passage for ideas, commerce and invading armies from the northwest. It is the Vardar, however, the final stage of the natural highway from central Europe to the eastern Mediterranean, that is Macedonia’s axial and main route, connecting the fertile plains of Thessalonica, Pelagonia and Skopje, and linking them, through its tributary, the Cema, with the plain of Bitola and the lake settlements of Ohrid and Great and Little Prespa.

This seemingly natural basis for an economic and ethnic national unit was permanently disrupted by the ancient Greeks, the foundation of whose civilisation was not the land but the sea. Greek settlements, whether situated on the shores of the Aegean, the Black Sea, the eastern Mediterranean, the Ionian Sea or, farther west, the Ligurian Sea, had sea not land lanes for their natural ‘interior’ lines of communication. The wild and rugged country behind was left by them to the ‘barbarians’ whose savage natures were so appropriate to its character. When the Etruscan and Carthaginian civilisations were flourishing in the western half of the Mediterranean, Macedonia already lay partitioned between the Aegean Greeks, living in the coastal neighbourhood of Thessalonica, on the Chalcidice peninsula and on the island of Thasos, and the Thraco-Illyrians of the hinterland, although archaeological discoveries are beginning to show that there, even as early as the sixth century B.c., Hellenic art and culture had penetrated extensively. A Hellenistic gold death-mask, a bronze mixing-bowl and other items from this period now in the National Museum of Belgrade have been excavated at Trebenište to the north of Lake Ohrid. The Museum of Skopje holds a similarly dated bronze Bacchante found at Tetovo. But the Illyrian civilisation, and its accompanying economic

3

![]()

and military strength, was gradually broken by waves of Celtic invaders, a process which paved the way for the rise of the kingdom of Macedonia in the fourth century B.c.

In this era eastern Macedonia was dominated by the Greek island of Thasos. Conquered from the indigenous Thracians by settlers from Paros in the eighth century b.c., Hellenised Thasos had gradually established its control over the more accessible and profitable parts of the mainland. Supplementing its own natural wealth with the rich agricultural produce of the coastal plains and by exploiting the gold mines of Krenides (Philippi) and Mount Pangaeus, in return the island promoted the Hellénisation of eastern Macedonia’s Thraco-Illyrian population. The discovery ofits coins as far afield as Transylvania, Hungary, Moravia and Germany are an indication of the importance of Thasos, which was also in commercial relations with Phoenicia, Egypt and the Barbary Coast.

While Philip II (359-336B.C.) ofMacedon receives the credit for creating the first national synthesis of the Greek population of Macedonia’s coastal cities and the Illyrian and Thracian tribesmen of the interior, his achievement was founded upon this gradual germination of Greek culture among Macedonia’s non-Greek population during the previous centuries. Nevertheless, by establishing his ascendancy over the Greek city-states to the south and drawing upon their deeper rooted civilisation, Philip furthered the Hellenisation of his kingdom to a degree sufficient to give his son, Alexander the Great, the opportunity of victoriously championing the Greek accomplishment against its world rivals.

In Europe, whatever unfulfilled intentions Alexander may have had, the frontiers of Macedonia underwent little change. Both rewards and danger from this direction were relatively small. Eastwards, on the other hand, as far as India and into central Asia, he repeated the work of his father in Macedonia on a gigantic scale. Cyrus and his Achaemenian successors had dreamed of a single world state under the generous and enlightened rule of the divinely appointed Persian king. Alexander turned this dream into a Macedonian reality, creating an empire, the peoples of which became imbued with a sense of unity transcending their racial and historical differences. Hellenic culture fol

lowed in the wake of Alexander’s conquests. The ‘ core’ of the Hellenic world expanded from its ancient confines of the Aegean Sea to include the whole eastern Mediterranean. Alexandria and Antioch, with their wealthy Egyptian and Syrian hinterlands, joined such older Greek cities as Athens, Pergamum and Rhodes as its formative influences and rapidly grew to dispute their leadership of a civilisation that was changing from Hellenic to Hellenistic. Farther east, after touching more lightly the highly developed civilisations of Babylonia and Persia, Hellenism settled again in the receptive soil ofBactria, Sogdiana and Gandhara. There the art and culture of Greece, bequeathed during Alexander’s brief dominion and continued under Seleucid and Kushan rulers, sponsored the first to fourth century a.d. Buddhist art of Gandhara in northern India (Pakistan), and the sculptures of the third to fifth centuries a.d. discovered at Hadda, near Jelalabad in Afghanistan. It even travelled far beyond the limits of Alexander’s empire, as can be seen from the Fayumtype wall painting of Buddha at Miran in Sinkiang. To his Macedonian homeland, Alexander bequeathed a more lasting, even permanent legacy, an orientation towards the east which ever since has been reflected in its religious art.

The cultural influences that flowed eastwards as a consequence of Alexander’s conquests have aroused more attention than those which spread from east to west. To the Greeks, mankind fell into two classes — Greeks, and others of a lower order. Alexander and his Macedonian nobles, however, possessed no such limiting tradition. They found, particularly in the Persian Empire, a higher and more ancient standard of culture and a richer and more graceful manner of living than they had known in their own homeland, higher even than in Greece itself. Moreover, instead of the Greek system of small and quarrelsome city-states, they met there a conception of empire, which, with all its — not unattractive — despotic qualities, rejected petty nationalistic tendencies. In ideals, to some extent, as well as in territory, the Macedonian Empire was a successor to that of Achaemenian Persia.

The vision and vigour that had won Alexander his victories in war were turned to peaceful ends as he put into effect his plans for partnership between his GrecoMacedonians and those Persians and others who, but

4

![]()

a short time before, had been his adversaries. He offered the latter posts in his court and his army and encouraged his nobles to intermarry. This far-reaching social partnership begun by Alexander and, incredible as it seems, firmly established in the brief time at his disposal, ensured the rooting of Hellenistic culture even where it met with strong competitors. Although the impetus slowed down after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, no immediate reaction occurred against Hellenism. Rather was it the reverse ; later indigenous or other rulers of non-Hellenic origin tended to pride themselves on their adherence to its traditions, even to the point of taking Greek names. Nevertheless, Greece, the source of Hellenism, was in a state of decline and, as the Macedonian impetus lost its force, Persia correspondingly increased its ideological contribution to the cultural federation.

In the cults of Apollo and Mithra, both identified with the sun and with youthful beauty, Greco-Macedonians and Persians found themselves on a common religious ground. It is impossible now to say how much each cult absorbed from the other, but it is likely that the interrelationship of the two was an important factor in the cultural unity of this vast region. Although Persia rejected Apollo and Greece Mithra, in later centuries troops of the Roman Empire carried from Asia the westernised, Apollo-influenced cult of Mithra throughout the non-Hellenic European provinces of Rome and established it as the deadliest rival of Christianity until the fateful decision of Constantine in favour of the latter. However, it is indicative of the then relative strengths of Roman and Persian civilisations that this was not a two-way traffic in religious ideas. In Persia, Mithra never became a supreme deity and an Apollo cult was negligible or nonexistent.

Alexander’s defeat of Darius not only assured Hellenism its role as one of the formative influences in world civilisation, it decided that the political and cultural centre of the Ancient World should be the eastern Mediterranean instead of Achaemenian Persia. Had the victory been gained by Darius, the eastern Mediterranean would have become an outlying satrapy of the Persian Empire, in art and thought as provincial as in politics. Instead, for all Hellenism’s now slowing impetus, the eastern Mediterranean, as metropolitan

region, became the hub of every main route of the Ancient World. All roads led to it, as in a later era and empire they were to lead to Rome, and along them travelled ideas from every component civilisation of Alexander’s empire as well as those lying beyond its boundaries. Macedonia’s exposure to and willing absorption of these ideas and foreign influences, mainly Asiatic in origin, were responsible for giving to much of her early Byzantine art its distinctive characteristics.

The moulds of the civilisations of Greece and Rome were the temperate climate of the Mediterranean, with its sunshine and clear sparkling air, and its — originally — forested mountain slopes and island-studded seas that provided cheap and easy means of communication. Extremes of heat and cold, vast mountain ranges and plateaux, gave altogether different characteristics to the inhabitants of Iran, the Caucasus and die interior of Asia Minor. Different again were the riparian peoples of Egypt and Mesopotamia, where intense heat was associated with more or less inexhaustible agricultural wealth, and the monsoon-governed, agricultural populations of tropical India. Similarly, the Syro-Arabian deserts, where a fierce sun and an unremunerative soil permitted little opportunity for developing the refinements of life, moulded their inhabitants differently from their Semitic brothers who were the builders of highly developed civilisations based on commerce in Mediterranean Syria and the southern parts of the Arabian peninsula. To the north, the mountains, plains and forests of eastern Europe and the vast steppes of Russia were the homelands of an unsettled and uneasy pattern of peoples, contemptuously termed barbarians by the Greek historians, but possessing characteristics that were creative as well as destructive.

In varying measures, these diverse elements had contributed towards the social structure of Alexander’s empire and were to form the foundations of the Christian world. Their interaction, a process that had begun long before Alexander, but to which he had given a dynamic impetus, continued to develop in spite of the break-up of his territorial empire. When, six centuries later, Constantine established his capital on the shores of the Bosphorus, his East Roman or Byzantine Empire was fundamentally a perpetuation of the Hellenistic tradition and, besides its Roman heritage, it

5

![]()

acceded automatically to the living legacy of western Asia’s past. The civilisations of western Asia and Egypt, therefore, were as much the context of Macedonian history and art as were Greece and Rome, and it is necessary for our understanding of Macedonian art, to examine briefly their potential contributions.

Egypt

In many ways the Nile valley was a cul-de-sac of the Ancient World. Immensely wealthy, but easily defended with the help of its formidable natural obstacles, it was a difficult prize to gain, and one, moreover, which led to nowhere else profitable of conquest. For fifteen hundred years or more prior to the Hyksos invasion midway through the second millennium b.c., Egypt had enjoyed an undisturbed and therefore unique opportunity to develop an exclusive civilisation, the foundations of which it had originally imported from Sumerian Mesopotamia. The cumulative result of this isolation, emphasised by the brief but hated Hyksos dominion and subsequent contacts "with less highly developed civilisations during the Egyptian imperial phase, was a deeply rooted dislike and contempt for all foreigners. Internally, this was matched by a conservatism and a strong belief in the superiority and rightness of all things Egyptian.

This national attitude of innate Egyptian superiority persisted even through the degenerative period of the later dynasties of the New Empire and the Persian tyranny into which they dissolved. Nevertheless, by that time Egypt had lost the strength which had enabled her to throw off the Hyksos yoke, and, in the fourth century b.c., it was no native prince, but a new conqueror, Alexander, who ‘liberated’ Egypt. An important and a permanent consequence of this ‘liberation’ was the establishment on Egyptian soil for the first time of a new, virile Greek colony. Y et, however much the internationally minded Greeks of Egypt might occupy the limelight of intellectual thought, the Egyptian people maintained unchanged their deeply rooted attitudes towards the rest of the world, particularly in anything that affected their religion. In fact, the more thoroughly they had to submit to political overrule, the more stubbornly did they resist foreign dictation in matters of the spirit.

Egyptian life and Egyptian belief in the after-life were both based upon and revolved around two ‘miracles’, the triumphant daily rebirth of the sun and the triumphant annual rebirth of the river. It was these two ‘miracles’ which conferred upon Egypt a greater fertility of soil and a consequent continuing material prosperity than any other nation could claim. It is not difficult to see how the infallible regularity with which these two events occurred was regarded as divine confirmation that, with equal infallibility, life would succeed death and that the land and people of Egypt enjoyed divine favour above all others. From them arose the twin cult of the Sun-god and Osiris, the divine son of Isis whose death and rebirth reflected the religious aspirations of all Egyptians. But the circumstances of Egyptian fife were not conducive to mental stimulation; a pleasanter existence than the one Egyptians were able to enjoy in their earthly fife, with its luxurious, divinely given and divinely renewed abundance, great cities and splendid temples, presided over by a god-Pharaoh, was beyond their powers of imagination. The Egyptian Hereafter, therefore, for all the attention that was paid to it, was very little more than a perpetuation of the more comfortable aspects of a prosperous earthly existence.

In line with this ideology, religious art was representational and, in so far as the ordinary Egyptian was concerned, generally realistic. Size was used as an expression of divinity, but representations of godPharaohs and their fellow divinities were principally characterised by an overwhelming sense of impersonality and, as a general rule, an absence of any quality of idealism. The ceremonial practice of Egyptian religion was in the hands of a strongly entrenched and powerful priesthood. They alone held, and jealously kept, die keys to the sacred mysteries, and they ensured that no ordinary mortal might communicate with the divine powers other than through their agency.

Self-sufficient and self-centred, the direct influence of the civilisation of Ancient Egypt beyond its frontiers was small in relation to its own greatness and to the contributions of its contemporaries. An arrogant disinclination to learn made the Egyptians bad teachers. In, for instance, its doctrine of a resurrection, Egypt made an important contribution to a basic religious concept, but it had to be interpreted and conveyed to

6

![]()

other peoples through such intermediaries as the Jews and the Alexandrian Greeks, and perhaps also, though to a lesser extent, through their Syrian vassals dining the Egyptian imperialistic phase.

The university of Alexandria, the centre of neo-Platonic philosophy, was essentially Greek; nevertheless, it flourished significantly in its Egyptian environment, that, after the rise of Parthia, included the principal trade routes between the Mediterranean and India. Alexandria’s importance as a clearing station of ideas was immense, and it is difficult to exaggerate the value of the links which its university and its markets jointly maintained between Hellenism and the civilisations of India. Perhaps Egypt’s most important contribution to Christianity was monasticism. Although almost certainly inspired by the example of Buddhism in India, the credit for the Christian evolution of this powerful movement belongs very largely to the Egyptian Church.

Eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Mesopotamia

In sharp contrast with Egypt, this geographically indeterminate area straddled important highways of the Ancient World. Around it, and with close contacts, were the Aegean states, the Caucasus and Armenia, Iran, Mesopotamia and Syria. Such a region was fated to be inhabited by a mixed and changing population; but two peoples, above all the others, were jointly responsible for its most constructive contribution to the early Christian era, in spite of the fact that both disappeared from history about the eighth century b.c. These were the Hurri, grouped mainly in northern Mesopotamia, and the Hittites, a confederacy of tribes, whose territory extended from northern Syria across the whole of eastern Anatolia. Although militarily the weaker, usually subject to some more powerful race, and imitators rather than originators, the Hurri were culturally the stronger of the two, and, in matters of religion and social progress, their influence played a key part in the development of the powerful Hittite civilisation.

It was in the supernatural forces of the weather that the Hurri-Hittites found their supreme deities. One was Teshub, the Weather-god, a divine personification

of the mountain storms. ‘ In Syrian art he often stands alone, wielding an axe and a symbolic flash of lightning ; in Anatolia itself he drives in a primitive kind of chariot drawn by bulls over the heads of personified mountains.’ [1] Teshub’s consort was Hebat, the Sungoddess. Sometimes one, sometimes the other was accorded primacy, a situation which significantly reflected the position of women in Hurrian civilisation. Bound together with Hebat’s queenly attributes was an even more fundamental association with the conception of the Great Mother Goddess, the deified personification of the maternal, creative and reproductive powers of the earth.

Throughout the Hurri-Hittite period we see a general tendency to assimilate the attributes of subordinate and local gods into the characters of the two principal divinities. The many minor deities on record included, however, some of an unusually ethical nature ; among them, gods ofjustice, righteous dealing and sincerity — uncommon attributes of gods in the latter part of the second and the beginning of the first millennium b.c. Another exceptional feature of Hurri-Hittite religion was its insistence upon sincere and contrite confession of sins. Man’s misfortunes might arise either from his having done wrong, thus offending the gods and calling their punishment upon him, or they might be caused by the activities of evil spirits. If the former, he had to obtain divine forgiveness through penitent confession, purification and sacrifice ; if the latter, he must defeat the evil spirits with the help of magic charms.

It was a cardinal feature of the Hurri-Hittite religion that not even the king enjoyed any form of immunity from its laws. Kingship was conferred by the nation, not by the gods. The first duty of the king was that of high priest, and in the carrying out of his priestly functions no Hittite monarch permitted himself illusions of divinity or regarded himself as anything but the representative of his people.

Too little is yet known of Hurri-Hittite religious art for very dependable conclusions to be drawn, but a general tendency towards representation of deities in relief rather than in the round may perhaps be noted. The curtain was rung down upon the Hurri-Hittite

1. O. R. Gurney, The Hittites (Harmondsworth, 2nd edition, 1954), p. 134.

7

![]()

civilisation by the rising power of Assyria ; but fortunately this left undestroyed a truly remarkable and enduring legacy, which modem research is only now enabling us to begin to appreciate. One of its heirs was early Greek religion, which drew to a considerable extent upon subjects of Anatolian origin. The cults of Dionysus, of the Samothracian Cabiri, Cybele-Rhea the Earth and Great Mother Goddess of the ancient Greeks, and Demeter all had deep roots in Asia Minor. It is significant, too, that in the early centuries of Christianity, it was the identical region of northern Mesopotamia, northern Syria and Cappadocian Anatolia, that once more provided leadership in the development and propagation of so many of the principles its population had pioneered in the Ancient World a thousand years before.

Persia

With the rise of the Achaemenian dynasty in the sixth century b.c., Persia succeeded to a joint inheritance of the Iranian empire of the Medes and the ancient, highly developed civilisations of the Mesopotamian plain. This fusion of military, political and social genius rapidly established the Persian Empire as a world force rivalled only by the city-states of Greece. Although Alexander’s conquest of Persia conferred upon Hellenism a brief supremacy, gradually the military, social and ideological forces of Persia made their recovery. In 248 b.c., less than a century after Alexander’s victory over Darius, a successful Parthian revolt restored Persia’s independence and in 129 b.c. a further victory expelled the authority of the Macedonian Seleucids to the Syrian banks of the Euphrates. Earlier a subject people of the Achaemenian Persians, the Parthians belonged to the northern edge of the Iranian plateau and consequently possessed close links with the Scythian nomads of the southern Asian steppes. Despite this origin, the rise of Parthia represented, in fact, a national Persian reaction against the foreign influence of Hellenism, which was visualised as the corrupter of the country’s brave traditions of independence. For the next four centuries one of the world’s leading military powers, Parthia barred any spread farther eastwards of direct Hellenistic influence, whether it appeared under a Seleucid or a Roman

standard, and provided a shield behind which the Persian nation gathered its strength for the massive counter-attack, ideological as well as military, which was to be launched by the Sassanian dynasty. The wars of the fifth, sixth and early seventh centuries between the Byzantine and the Sassanian empires were in all their fundamentals a renewal of the ancient, still unsolved, Greco-Persian rivalry.

Throughout the centuries, however, and irrespective of the military situation, the different ideologies of the two great civilisations had been intermingling. The deeply rooted culture of the Orient, of which Achaemenian Persia had assumed the leadership, had profoundly affected the Greco-Macedonian conquerors and the impact was magnified by the essentially Greek characteristic of intellectual curiosity and the limitless Greek capacity for absorbing, adapting and adopting new ideas.

This proved of particular importance in matters of religion. The religion of the Achaemenian Persians and the art that interpreted its ideology sprang predominantly from the savage grandeur of the mountain ranges and harsh desert wastes of the Iranian plateau. The Achaemenian kings were ‘ great kings ’, and ‘ kings of kings’. More than this, as part of their Mesopotamian inheritance, they were the divinely appointed, earthly representatives of the gods. Every opportunity was taken to emphasise these Achaemenian qualities of superhuman greatness and divine perpetuity in the moments they left to posterity, both in the inscribed texts and in the massive hierarchic scale of their likenesses carved on mountain faces. All that they turned their minds and hands to, whether creation or destruction, was commensurate with their claim to superhuman, semi-divine dignity. The principal monuments that have been left to us of Achaemenian art are the ruins of immense royal palaces and great rock tombs, constructed high up the sides of mountains, their façades modelled upon the façades of these same palaces. It was at the majestic portals of his palace that the Persian king revealed himself to his mortal subjects, and it was through similar carved portals that the dead king entered his mountain tomb on his way to appear before the gods. Achaemenian religious sculpture, particularly that displayed on the rock tombs, was essentially carving in relief, for no

8

![]()

mortal being but the king, at his death, might approach the gods.

The supreme god was Ahuramazda, the creator of heaven and earth. At Ahuramazda’s delegation the Achaemenian king governed his dominions. Below this deity were divine personifications of the elements, the sun, the moon, earth, fire, water and the wind. The ritual worship and the sacrifices to these gods were in the hands of a priestly class, the Magi, whom the Persians inherited from the Medes. Early in the Achaemenian period and more or less contemporary with the rise of Buddhism in India, this religion underwent a gradual transformation into a new, more ethical and monotheistic form, known, after its founder, as Zoroastrianism, or Mazdaism. In this, Ahuramazda became the deification of the forces of good, engaged in ceaseless struggle with those of evil.

The Persian conception of kingship as a divinely conferred appointment to rule not only Persia but the world was of immense significance to the development of subsequent religious thought. L’Orange remarks, ‘the kingdoms in the Ancient Near East mirrored the rule of the sun in the heavens. The king amongst his vassals and satraps was a reflection of the heavenly hierarchy. The king was “The Axis and Pole of the World”. In Babylonian cult the king was “The Sun of Babylon”, “The King of the Universe”, “The King of the Four Quadrants of the World”, and these titles were repeated in ever new adaptations right up to the Sassanian period when the king was the “frater Solis et Lunae”.’ [1]

Though the king never formally assumed the mantle of divinity during his earthly existence, the tradition developed of rendering him the conventional attributes of his impending apotheosis as an integral part of court and religious ceremonial. One aspect of this lay in the gradual development of the identification of the king with the sun, which he was held to personify. This conception was adopted in the Roman Empire by Nero as part of the process of his deification. Later emperors, including Caracalla, Alexander Severus, Constantius II, Constans, Valens, and Honorius, copied his example and represented themselves thus on their coinage. The symbol is even echoed in early Christian art. It is to be found, for instance, in the early third-century Roman mosaic of Christ-Helios driving a horse-drawn sky chariot, and in a similar, end-fourth-century mosaic in the chapel of S. Aquilino, in the church of S. Lorenzo, Milan.

More important, because of its wider and more enduring acceptance into Christian iconography, was the Persian convention of representing the king enthroned upon a round clipeus or shield, signifying the cosmos, of which reputedly he was the supreme and divinely appointed ruler. Winged creatures held this aloft. Sometimes these might have human forms; sometimes they might represent real or mythical beasts, or birds. Three examples of the adoption of this convention by the early Christian Church have survived in Thessalonica. In the apex of the dome of St George can be seen the remains of an end-fourth-century mosaic depicting four angels supporting a circular clipeus containing a luxuriant wreath of flowers, foliage and fruits. In the centre of this, now almost entirely lost, appeared a representation of Christ. The second example, also in St George, on the tympanum of the ciborium of Mosaic Panel No. 7 (Pl. 20b) shows the bust of Christ in a clipeus or medallion held aloft by two angels. The third, dated about a century later, is the mosaic showing the visions of Ezekiel and Habakkuk in the apse of the small church of Hosios David. Christ appears enthroned in the centre of a circular clipeus, now transformed into a translucent double rainbow. Emerging from behind the clipeus, but no longer supporting it, are four creatures, here developed into the symbols of the evangelists. With the later evolution of the Byzantine ‘ cross-in-square ’ church the four attendants, portrayed realistically as the four evangelists, take their place in the pendentives of the dome of which Christ Pantocrator occupies the apex. Here, it is interesting to note, they have returned to the position — architecturally — of supporters. To-day, the Oriental cosmic clipeus that originally signified the impending apotheosis of the ancient Persian Cosmocrator still figures in Byzantine iconography. It is found in such scenes as the Dormition, the Transfiguration, the Judgement Day and the Ascension, where, although Christ is appearing to men, emphasis is placed upon His assumption of divinity rather than upon His earthly life.

1. H. P. L’Orange, Studies on the Iconography of Cosmic Kingship in the Ancient World (Oslo, 1953), p. 13.

9

![]()

The anti-Hellenistic foreign policy of the Parthian Empire did not imply the complete cessation of the ancient caravan trade that, particularly after the Macedonian conquest, had crossed Mesopotamia and Iran to and from the Mediterranean in the west and India, Sinkiang and China in the east. This traffic was too valuable a source of income and foreign goods for the Parthians to interrupt it entirely. Yet transit facilities for merchants became more difficult and, in the case of nationals of rival powers, were probably wholly withdrawn. Greek could no longer deal with Greek as he passed from one Hellenistic city to another between Macedonia and India. For centuries to come, the great bulk of the traffic that passed between East and West, in ideas as well as in goods, had perforce to be handled by Arab or Jewish middlemen.

However, apart from their opposition to Hellenistic ‘imperialism’, the Parthians were distinguished by their toleration. Even Hellenism was permitted rein, as long as it was an indigenous Hellenism and served the purposes of the state. The main Parthian religion seems to have been worship of the triad, Ahuramazda, Mithra and Anahita, and in all fundamentals it was an historical continuation of that of the Achaemenian Empire. Parthian subjects also enjoyed full freedom to worship other gods of their choice. Consequently, throughout the Parthian Empire, and particularly in Mesopotamia, Christianity was able to develop in circumstances of peace and legality while, beyond the Euphrates in the Roman Empire, it was suffering at least restriction, and often outright persecution.

In art and architecture Parthia was the forerunner of its more brilliant Sassanian successor, which replaced it in the first half of the third century a.d. Parthian art was of necessity sterner than Sassanian. Its artists were needed to play their part in the rebuilding of the Persian state in face of the seductive influences of international Hellenism. They were not, therefore, primarily concerned with beauty of form. They represented their kings and gods as heavy, powerful, static and hierarchic figures. In a land where gods of so many kinds and forms competed, representation could no longer be limited to relief. Parthian architects demonstrated the inexpugnable influence of Hellenism by their free use of sculpture in the round. Neverthe-

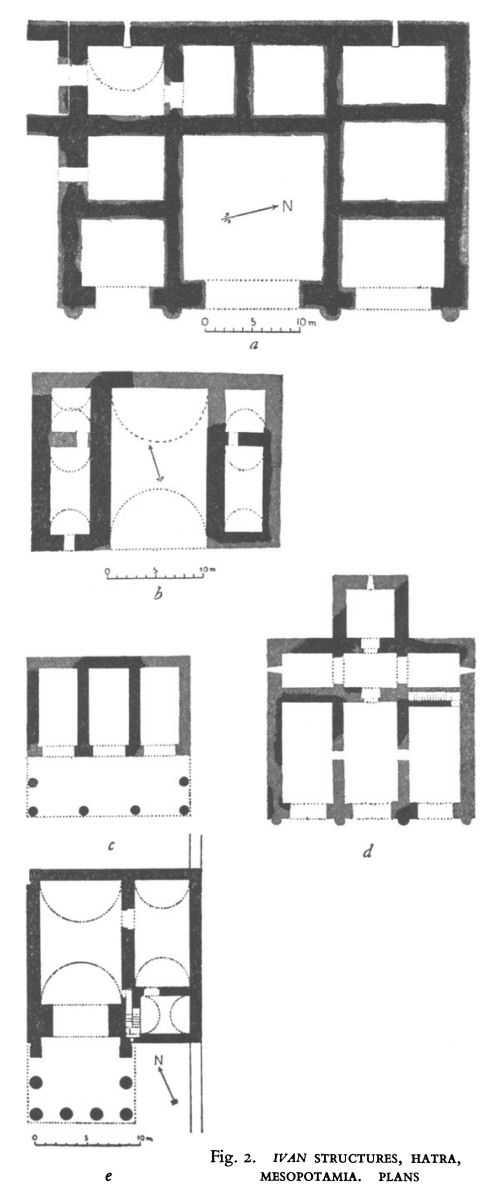

Fig. 2. IVAN STRUCTURES, HATRA, ESOPOTAMIA. PLANS

10

![]()

less the frontality which is such a strong characteristic of Parthian art reflected an ancient Iranian form. And, as can be seen from the excavations at Dura-Europos, this frontality appeared in Christian churches and Jewish synagogues as well as in pagan temples.

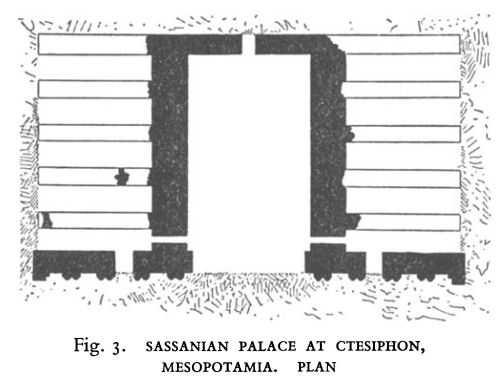

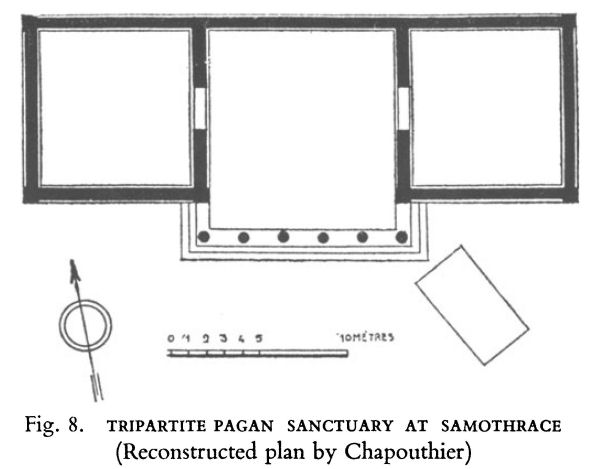

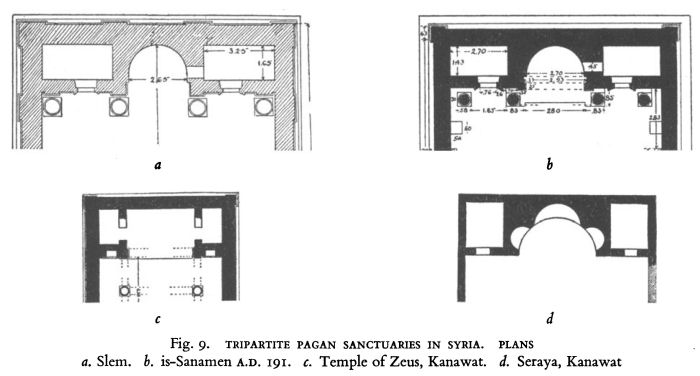

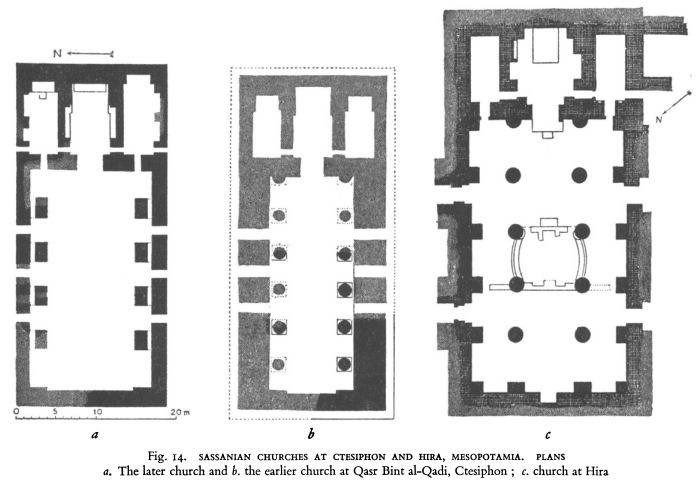

In addition to the Mesopotamian house, which with its courtyard was the traditional plan of the western Parthian provinces, Parthian architecture developed the Iranian type of i 'vanhouse, with three chambers opening on to a hall or courtyard. The central chamber was usually larger than those on either side and had a wider opening that often extended from wall to wall (Fig. 2). It was a form of architecture particularly suited to a palace, enabling the king to hold ceremonial audiences in the central bay, his attendants and service rooms to either side, while the public stood in the main hall or courtyard. Evolved originally from the entrances of the tents of the Irano-Scythian nomads, it was another aspect of the Persian city gate and the royal portals of the Achaemenian palaces. It became the common form of public ceremonial hall in Parthia and, under the Sassanians, it reached its culminating point in the magnificent, sixth-century palace at Ctesiphon (Pl. 18 d,Fig. 3 ). It is not surprising that with such

Fig. 3. SASSANIAN PALACE AT CTESIPHON, MESOPOTAMIA. PLAN

long traditions the Persian Christian Church should adapt the ivan form to its own purposes and should thus endeavour to render to the King of Heaven no less honour than the pagans rendered the King of Kangs.

The ruined examples of Parthian palaces that can still be seen to-day give little impression of their onetime splendour. Strabo ( 63 b.c.-a.d. 25) remarked that many houses about the Bay of Naples were constructed after the model of Persian royal dwellings, but, except possibly as small details on Pompeian landscape paintings, little trace has been found of these seaside Roman villas. Nevertheless, Strabo’s comment may well be reflected in the architectural details to be seen in the last phase of Pompeii’s decorative art. These, with their close parallels to the architectural façades represented in the dome of St George in Thessalonica, are characterised by an exotic fantasy and luxuriance of ornament that is undoubtedly Asiatic for, however much they may follow a temporary fashion of the Roman court and aristocracy, they are quite foreign to the genuine traditions of the Roman world. In retrospect, the glamour and attraction of Parthian Persia appears dim beside that exerted by its Sassanian successors, but, none the less, to a steadily increasing degree its influence was casting a spell over almost every phase of contemporary Roman life.

India

In the third century B.c., Asoka, the great Buddhist ruler of the Maurya Empire of India, recorded in his rock and pillar edicts that he had despatched missions to the Hellenistic kingdoms of Antiochos Theos of Syria and western Asia, Ptolemy Philadelphos of Egypt, Magas of Cyrene and Antigonos Gonatas of Macedonia. Their activities apparently included preaching the Buddhist faith as well as ordinary diplomacy ; but, in spite of Greek interest in Oriental ideas, Asoka’s envoys seem to have made little impression. Their message was not, in fact, very sensational. The early Buddhism of Asoka’s time proclaimed no new god, no powerful saviour able to promise his followers a paradise after death, no mysterious rites or fields for metaphysical enquiry. Instead, the Greeks must have viewed it as a rather tedious and impracticable code of moral behaviour. In schools such as those of the Stoics, the Epicureans and the Cynics, the Greeks had already formulated other conclusions, and against such strong native opposition Buddhism stood hide chance. Those, on the other hand, whom the Greek schools failed to satisfy were even less likely to find their answer in the message from India, the more so since

11

![]()

Buddhism had yet to evolve an anthropomorphic art, and the symbols it was using were too essentially Indian to make headway in the Hellenic, or even Hellenistic lands. There is no evidence that at this stage Greece or Macedonia were influenced by Indian ideas to any perceptible degree.

Nor did Hellenic culture make any noticeable impression upon Maurya India. As soon as Chandragupta, the first of the Maurya rulers, had succeeded in driving the Macedonian forces of Seleucus Nicator north of the Hindu Kush range, he welcomed diplomatic, cultural and commercial relations with his Hellenistic neighbour, and accepted a Syrian princess as his wife. Nevertheless, in Maurya art and architecture it was conquered Persia and not victorious Greco-Macedonia which proved the stronger formative influence from abroad. The ruins of the palace of Asoka, Chandragupta’s grandson, at Pataliputra reveal close resemblances with those of the Achaemenian palace at Persepolis, and Megasthenes, the contemporary Seleucid ambassador to the Maurya court, compares its splendours with those of Susa and Ecbatana. Asoka’s use of rock and pillar edicts, an important factor in carrying out his religious and social policies, was similarly a borrowing from Persia and Mesopotamia. Perhaps to an even greater degree than the Macedonians, the Indians became pupils in the arts of civilisation to the Persia that had been only temporarily absorbed within the boundaries of the Hellenistic world. But for India’s steadfast allegiance to Buddhism and earlier indigenous beliefs, the penetration of Persian influence must have been still deeper and longer lasting.

Thus, mainly through common injections of the stimuli of Persian civilisation, India was brought into cultural step with the east Mediterranean region. This process, beginning some two and a half centuries before the birth of Christ, cannot but have eased the way of any subsequent cultural exchanges. Although slow in taking effect, it proceeded with an impetus that was diverted neither by the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world, nor by the advent of the Scythian Kushan rulers in India. One example of significant parallel developments in religious art was the universality of the chariot-drawn symbol of the Sun-god or, in the Hittite version, the Weather-god. As an expression of the Sun-god it was used in fifth-century b.c. Greece. In the early Christian era, besides the Roman imperial and Christian examples already noted on page 9, we find it in a first-century representation of Zeus Theos in a Parthian temple at Dura-Europos, and in the thirdor fourth-century wall painting of the Hindu Sun-god Surya at Bamiyan. It was certainly not new at this period in India for it appears also several hundred years earlier at Bhaja and Bodh-Gaya.

The important direct contribution made by Hellenism to the religious art of India did not begin until nearly a century after the death of Alexander. When the Parthian conquest of Persia had driven a wedge between Seleucid Syria and the easternmost Hellenistic states, the isolation of the latter forced them to merge with the civilisation of India. It was then, under the Kushan dynasty, that they produced the Indo-Hellenistic, Gandhara sculptures and gave to Buddhism here, and perhaps at Mathura, its anthropomorphic art.

Yet, although the cultural and, in particular, the religious paths of western and eastern Hellenism, with their respective extensions into the Roman and Kushan empires, travelled on parallel lines rather than in association, they still followed remarkably similar courses. Contemporary with the beginnings of Christianity a new form of Buddhism had been taking shape. Without doubt this Mahayana Buddhism owed much to the same Hellenistic influences that had been responsible for evolving Gandhara art, and the parallels are many between its Indo-Hellenistic synthesis and the contemporary Jewish-Hellenistic religion of Christianity, although in their evolution the latter suffered a two and a half to three centuries’ handicap of official repression within the Roman Empire. From being little more than a moral code of limited practical application, Buddhism now evolved into a universal religion. No longer simply an ascetic moral teacher, the Buddha was now transformed into a god, like Brahma, an Absolute, who had been before all worlds and whose existence was eternal. His appearance on earth and Nirvana were explained as a device for the comfort and conversion of men. [1]

The practically simultaneous Christian and Buddhist

1. B. Rowland, The Art and Architecture of India (Harmondsworth, 1954), p. 32.

12

![]()

answer of nearly two thousand years ago to civilised mankind’s demand for a saviour-god proved to possess a world-wide application. Westwards, Christian missionaries took their message as far as the distant isles of Britain ; eastwards, Buddhists travelled with theirs to convert the ancient empire of China, where, later, they were followed by the Nestorian Christians of Mesopotamia and Persia. Inevitably, in time the two religions diverged, but it is significant that the causes of this were less the physical problems of distance and difficulties of communications than the physical and moral havoc that the great waves of barbarian invasions brought, in various degrees, to the civilisations of Europe, south-western Asia and China in the early centuries of the Christian era.

Mahayana Buddhism and its Indo-Hellenistic art continued to flourish in Gandhara until the catastrophic invasion of the White Huns in the sixth century, while, from A.D. 50 until 320, southern India prospered under the brilliant rule of the later Andhra dynasty. During the early centuries of this period, when for most of the time Christianity was a proscribed religion in the Roman Empire, a very considerable trade was in existence between the eastern Mediterranean and India. Most of this, though not all, as we are aware from the anonymous Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, compiled during the first half of the first century a.d., was in the hands of Arab middlemen.

It is not difficult to see an affinity between Buddhist thought and the ideologies of such religious sects as the Jewish Essenes or the Therapeutae of Alexandria, but that the penetration of Buddhist ideas into the eastern Mediterranean was not confined to the more esoteric groups receives a remarkable demonstration in Josephus’ account of the final Jewish stand against the Romans in the fortress of Massada in a.d. 70. The Jewish leader, Eleazar, proposes that, in view of the hopelessness of their struggle, they should first kill their wives and children to prevent them falling into Roman hands and follow this act with a mass suicide. In support of his argument Josephus quotes Eleazar as saying:

‘Yet if we do stand in need of foreigners to support us in this path, let us regard those Indians who profess the example of philosophy, for these good men do but unwillingly undergo the time of life, and look upon it as a necessary servitude and make haste to let their souls loose from their bodies ; nay, when no misfortune presses them to it, nor drives them upon it, these have such a desire of a fife of immortality, that they tell other men beforehand that they are about to depart, and nobody hinders them but every one thinks them happy men, and gives them letters to be carried to their familiar friends (that are dead) ; so firmly and certainly do they believe that souls converse with one another (in the other world). So when these men have heard all such commands that were to be given them, they deliver their body to the fire ; and in order to their getting their soul a separation from the body, in the greatest purity, they die in the midst of hymns of commendations made to them ; for their dearest friends conduct them to their death more readily than do any of the rest of mankind conduct their fellow citizens when they are going a very long journey, who, at the same time weep on their own account, but look upon the others as happy persons, as so soon to be made partakers of the immortal order of beings. Are we not, therefore, ashamed to have lower notions than the Indians ?’ [1]

This reference to Indian philosophy and precedents at a time of such dire crisis is an extraordinary testimonial to the hold which India must have exerted upon the thought and imagination of a people whose ramifications extended throughout the Mediterranean world, and it is noteworthy that the Massada incident occurred within less than two decades of St Paul’s journeys to Macedonia and within three-quarters of a century of the Jewish Diaspora. That this influence was neither superficial nor ephemeral is confirmed by the seventh- or eighth-century document of ‘John the Monk’, giving,in the history of Barlaam and Josaphat, a Christian version of the fife of Buddha, ‘a history which is good for the soul . . . transferred from the country of the Indians’. It seems a reasonable probability that the story which was set down in writing by John the Monk, and enjoyed widespread and lasting popularity, was no new import from seventh-century India, but one that had long been current in his native Palestine. Of even greater significance is the relationship between the apophatic or negative theology propounded by the ‘Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite’ and the Buddhist doctrine of Nirvana.

1. Josephus, Wars of the Jews, Book VII, chap. viii. Trans, by W. Whiston.

13

![]()

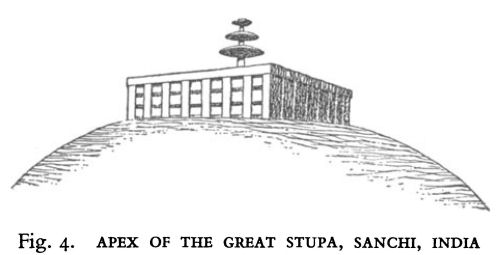

In the sphere of art, we shall consider the possible influence of Indian ideas in the expression on the face of Christ in the apse mosaic in the Thessalonian church of Hosios David (Pl. 48) in Chapter 9, Section 14. Three other, perhaps less significant, examples of artistic interrelation may be briefly quoted. The ‘Psamatia’ Christ, which appears on a fragment of a sarcophagus from Asia Minor, is remarkably similar, both in posture and technique of presentation, to contemporary representations of standing Buddhas. [1] In a third-century mosaic floor at Aquileia is a bust of an ‘Indian boxer’. A fifth- or sixth-century mosaic in St Demetrius at Thessalonica depicting a child being presented to the saint has two trees in the background ; both are shaped in the form of a three-tiered ‘umbrella’, the Indian symbol of the tree or axis of the universe which appears in an identical form at the apex of the stupa at Sanchi (Pl. IV and Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. APEX OF THE GREAT STUPA, SANCHI, INDIA

Lastly, but by no means least, may be cited the tremendous influence of monasticism on the development of early Christianity. The Christian version spread to Europe and western Asia from Egypt, but, as has already been pointed out, Egypt must almost certainly have obtained its original inspiration from Buddhist India. The possibility that a Buddhist influence continued to be expressed in western monasticism for some centuries is not to be disregarded.

The Semitic Peoples of Mesopotamia, Syria and Arabia

It is one of the most stubborn facts of history that despite endless and often violent divisions, the Semitic peoples have continued to maintain a fundamental unity. Even the great Jewish Diaspora of the second century A.D., a movement which gave the Jews unparalleled international connections and even deep roots in other lands, did not succeed in separating them from their historic homeland in western Asia. Similarly, for all the apparent differences between the urban Arab and his nomadic brothers, and however each may look down upon the other, the underlying concepts of both are identical. Right up to our own day the (now finally disappearing) sternly puritanical Semite of the desert has retained an ultimate moral ascendancy and, when the urban Semite has strayed too far from his old traditions, eventually his desert brother has descended upon him and ruthlessly purged him of his ‘impurities’.

To establish the fundamental Semitic tradition, therefore, we must consider the conceptions and way of life of the Semitic peoples beyond the cities. Broadly, there were two categories; the pastoral nomad, leading a tribal existence among the unproductive desert and semi-desert wastes of Syria and Arabia, and the caravaning or seafaring trader. The latter, in fact, by virtue of his commercial contacts was already beginning the first stage of the process of urbanisation.

Their environments the vast emptiness of the desert and ocean, such people led an austere, even harsh existence, physically and mentally governed by the scorching heat of the sun by day and the cold moonlit and starry expanses of the sky by night. There was time for thinking, time for conversation and the relating of tales, time for theological speculation and contemplation of the Absolute ; but little opportunity for the enjoyment of material possessions and refinements. The architecture of adherents of a civilisation of this nature was unlikely to prolificate archaeological remains, for their temples were not houses they had fashioned themselves, but the divinely erected and divinely appointed sky. If an object of particularly sacred associations needed a sanctuary, the means at hand was a portable, ceremonial tent, designed as closely as possible on the lines of the great sky dome. Their religious art was abstract and essentially nonrepresentational. It was characterised by an emphasis on geometrical design and a passion for filling in every

1. B. Rowland, Jnr., Art in East and West (Harvard, 1954). Figures 15 and 16 show a particularly interesting comparison between the Psamatia Christ and a third/fourth-century Buddha in the Museum of Kabul.

14

![]()

possible inch of space with symbols of good, lest the evil forces that inhabited the great expanses of the unknown might suddenly materialise and cause harm, as they too often did, in the shape of tempests, disease, famine and enemy tribes, in the people’s daily lives. Only when the Semites attained an urban existence did their worship include representational forms, as happened, for instance, in the case of the ‘golden calf’ of the Israelites. The true sacred object of the Israelites was the Ark of the Covenant, a wooden chest containing the tablets of the Law. Similarly, the prototype of Dhu-el-Shara, the chief god of the Nabatean Arabs of Petra, was a rectangular block of stone, in all probability a similar object to the sacred Kaaba worshipped in Mecca to-day.

A way of life appropriate to seafarers or pastoral nomads could not be fitted easily into a different context. The Semitic peoples who spread into agricultural areas, and traders who made their homes in foreign cities or the busy entrepôts that grew up at the intersection of caravan routes, had to adapt themselves to an urban life. In so doing, there was a natural tendency to adopt the customs of their more sophisticated neighbours. Their gods might remain more or less the same as those worshipped by their desert ancestors, but a tent or an open space appeared a mean, ignoble form of sanctuary beside the resplendent temples dedicated to the foreign gods. If, in copying such structures as these temples, a symbol of the great sky temple also was needed, a small but beautifully wrought dome or ciborium above the altar sufficed. Intermittently, in the effort to combat the lure of alien religions, Semitic abstract religious art gave way to representational forms. As can be seen in the synagogue excavated at Dura-Europos, in the third century A.D. some Jewish communities had even relaxed their scruples to the extent of covering the walls of synagogues with religious pictures to meet the competition of Christianity, and doubtless other religions such as Mithraism.

Nevertheless, however much the urbanised Semite might compromise in matters of form and method, wherever he went and wherever he stayed, he maintained with remarkably little change the fundamental identity of himself and his religion. As a result of this neutral identity in a divided world, the Semitic trader

retained his ability to buy in India what he could sell in Egypt, in Mesopotamia what he could sell in Rome. When the rise of Parthia put an end to the full ‘internationalism’ of Hellenism, it was he who replaced the Greek as the common denominator of the civilised world, and by virtue of this, continued to a very large degree the henotheistic impetus of Alexander.

In art and architecture, the urban, international Semites were carriers and adaptors rather than creators of original forms. It was an invaluable and, indeed, for the Christian civilisation of Europe and western Asia, an indispensable role ; for what the Semitic trader conveyed from one land to another was, ultimately, the expression of ideals. Discussing the art of the Arab city of Palmyra, Rostovtzeff provides us with a clue to the perpetuation into Christianity of the ethical ideals of the Hurri-Hittites centuries after their civilisation had, apparently, disappeared.

The sculpture of Palmyra represented by hundreds of busts and bas-reliefs, showing figures of gods and men and ritual scenes, presents in the treatment of the heads and bodies such softness and lack of vigour, such helplessness in modelling the limbs of a human body, such inclination towards the pictorial element and the minute rendering of details of dress and furniture (peculiarities which are entirely foreign to Greek sculpture and are typical of the eastern plastic art in general), that we can hardly call this sculpture Greek or GraecoRoman. If we look for affinities we shall see that the nearest parallels to Palmyrene sculptures will be found not so much in Babylonia, in Assyria, or in Persia, as in the north Semitic countries and in Anatolia, in the art which has been quite recently revealed by archaeological investigation of north Syria and Anatolia and which we call by the general name of Hittite. Such sites as Sendjirli, Carchemish, and Tell Halaf with their hundreds of statues and bas-reliefs show, in spite of the long stretch of time which separates them from the earlier Palmyrene sculptures, unmistakable affinities with Palmyrene plastic art. We may say, without being in danger of misleading the reader, that the sculpture of Palmyra is the Hellenised offspring of Aramaean and Anatolian plastic art. [1]

The architecture of Petra tells a slightly different story but one that follows similar lines. The original homeland of the Nabateans, according to their own traditions, lay to the south of Petra, almost certainly

1. M. Rostovtzeff, Caravan Cities (Oxford, 1932), pp. 147-8.

15

![]()

somewhere in the Arabian peninsula. For all the obvious contribution of Hellenistic and Roman art to the style and, in particular, the sculptural decoration of the later monuments, the underlying architectural conception of Petra is Iranian. The earlier temples are devoid of any western influence and, of the later, the Khasne (Pl. i8fc), one of the most obviously Hellenistic monuments, is the rock tomb of a Nabatean king and still a fundamentally Achaemenian conception.

From the earliest historic period until the sixth and seventh centuries a.d., when a combination of general insecurity and the final breakdown of the Marib dam instigated a large-scale migration northwards and the militancy of Islam brought about the severing of EastWest connections, the southern and some of the other coastal regions of the Arabian peninsula were the scene of a flourishing and highly developed civilisation exerting an important impact upon that of the Mediterranean. Excavations at Bahrein in the Persian Gulf are now revealing the advanced standards enjoyed by city trading stations operating the commercial routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus civilisation of India in very early times. In all probability traders of the same south-eastern Arabian cities brought the civilisation of Sumer to the early kingdom of Upper Egypt. Many centuries later the great Spice Route from India to the Mediterranean passed through and enriched the southern Arabian cities, the prosperity of which was further enhanced by the Parthian interruption of the direct overland road crossing northern Mesopotamia, and by the insatiable Roman appetite for the exotic products of the East.

To-day, among the many storied houses of the Hadhramaut one can find the astonishing spectacle of specimens of Dutch architecture, an indication, not of Dutch penetration, but of the fact that Hadhramaut trade has extended as far east as Indonesia and that, as from time immemorial, the southern Arabian trader has brought back to his homeland anything he had found abroad that seemed good to him. The most striking and characteristic architectural features of southern Arabia, however, are the great, well-proportioned, high buildings, whether in use to-day as the twenty-storied castle of Ghomdan in San’a, or in ruins as the ancient dam of Marib. As for their ornamentation, the tenth-century Arab geographer from southern

Arabia, al-Hamadani, tells us that one could see ‘ figures of all kinds sketched upon them ; wild and ravening animals . . . eagles with flapping wings and vultures pouncing upon hares . . . herds of gazelles hurrying to their death trap, dogs with drooping ears, partly leashed and partly loose, and a man with a whip, amidst horses’. These are Iranian and Irano-Scythian motives, and, whether received directly or via Byzantium, are one more indication of the powerful influences emanating from Irano-Mesopotamia since remote antiquity.

The Semitic artists were not content merely to copy the art forms of their neighbours, they would employ techniques they had observed in use in other lands. A good example of this, all the clearer for its rather clumsy naïveté, appears in the synagogue wall paintings of Dura-Europos executed about a.d. 245. Comparing them with the paintings in the Parthian temple of Zeus Theos, dated a little more than a century earlier, we find again the frontal poses, the gradation of stature according to hierarchic importance, and the verisimilitude of detail combined with lack of individual personality. On the other hand, the static and formalised effect has gone. There is movement, a movement that the painter’s brush has only momentarily arrested. Most striking of all is the impression that, for all their naïveté and clumsy postures, the figures represent human beings who are acting a story in the present tense. This impression is not even destroyed by the hierarchic nature of some of the paintings. Samuel, in the scene in which he anoints David among the sons of Jesse, stands considerably larger than the rest, but in no way does this appear to give him the stature of a god. The storytelling rather than ritual intention of the paintings is underlined by their narrative styles. In some cases the theme of one of the Jewish sacred books is presented in a series of isolated episodes. In others an attempt is made at a more continuous effect by running several incidents together within a single frame.

These narrative conventions, both of which became prominent features of Byzantine art, were not new to the east Mediterranean world. They had figured in the art of Sumer, ancient Egypt and Phoenicia. Yet, that the Jews of Syro-Mesopotamia went so far back in time for their models is unlikely for, as Rostovtzeff

16

![]()

has convincingly argued, [1] others were to hand. Both narrative forms appeared in second century B.c. Indian sculptures at Bharhut, where companion pieces very clearly display Persian influence, and in the relief carvings decorating the late first-century b.c. gateways of the stupa at Sanchi. [2] Following Rome’s expansion into western Asia, the second, or grouped type, became a popular artistic device in the Empire, appearing, for instance, in the early second-century Column of Trajan and, some half-century later, on that of Marcus Aurelius. In the third century, it was used by Christian artists in the Roman catacombs, for example to illustrate the story of Jonah in the cemetery of Callixtus. Both are used in Thessalonica’s early fourth-century Arch of Galerius (Pl. 8). But it was only when the Peace of the Church promoted a demand for a popular religious art, and with the removal of the centre of gravity of the Empire to the eastern Mediterranean, that the possibilities of both forms entered upon a new and greater period of exploitation.

Thus, in the realm of ideas, the Semitic contribution to early Christianity and Byzantine civilisation was twofold. Firstly, there was the powerful impetus towards an intellectual monotheism which stemmed from the austere and puritanical nomads of the deserts and voyagers of the seas. Secondly, a task to which they succeeded the Greeks after the rise of Parthia, there was the effective maintenance of free avenues of thought, irrespective of considerations of politics, distance or time ; for ideas were carried not only from country to country, but from age to age. It was the latter achievement, much of the credit for which belonged to the urban Semites, which ensured the orderly progression of the Hellenistic world into that of the Byzantine.

In architecture, the original Semitic contribution lay mainly in the ideological conception behind the domed, centralised church (though probably it had but little to do with its technical evolution) which attained a logical end in the domed mosque. In art it gave an emphasis to abstract form and design. An example, showing, incidentally, how strongly imprinted had been the influences of Hellenism, is the ornamental façade of the palace of M’shatta, in Syria. Yet, although Semitic inspiration tended generally to express itself in abstract forms, as Cumont [3] and L’Orange [4] have shown, it is likely to have been responsible for one important detail in the early iconography of Christ — the raised, open, right hand that we find in the apse of Hosios David and elsewhere in the late fourth to sixth centuries. In the books of the Old Testament reference continually occurs to Jehovah’s outstretched right hand — to use the Psalmist’s words, ‘Thou hast a mighty arm : strong is thy hand, and high is thy right hand’. [5] Throughout the Ancient Near East the gesture expressed divine omnipotence. By extension, it could signify salvation or, in the case of an angry god, destruction. But it was essentially a gesture of divinity, to be made only by the god himself or at his delegation, and, as such, was adopted particularly by the Semitic peoples. When King Jeroboam stretched his right hand against one of Jehovah’s prophets, it withered.

But, also of no small importance to later ages was what has been termed the ‘adaptive’ art of the Semitic peoples. Through their continual fertilisation of the art forms of one region or time with those of another, they played an essential part in the stupendous cooperative inter-racial effort which so long maintained the Eastern Mediterranean in its position of world leadership in the arts as well as in the religions of civilisation.

Celts, Scythians and their Successors

Beyond the northern periphery of Alexander’s conquests were two other powerful groups of peoples, the Celts and the Scythians. Documentary history has recorded little more than the comments of those who suffered from their destructive raids, but recent research has indicated that the usual Greek and Roman view of the Celts, Scythians and kindred peoples deserves considerable revision. Both groups were pastoral, though warlike, peoples, their social structure tribal; the Celts conditioned by the forests, mountains, fertile plains and rivers of Europe, the Scythians

1. M. Rostovtzeff, Dura-Europos and its Art (Oxford, 1938), chaps. 3 and 4.

2. Ibid.

3. F. Cumont, Fouilles de Doura Europos (1926), p. 70 et seq.

4. H. P. L’Orange, op. cit. p. 153 et seq.

5. Psalms lxxxix, 13.

17

![]()

by the vast steppe-lands over which they and their herds moved constantly in nomadic fashion. The Celts, northern neighbours of the Illyrians, undermined the latter’s vigorous civilisation by their raids around the fourth century b.c., and thus facilitated the transformation of the Macedonian kingdom into a powerful and ambitious state. Celtic depredations in the southern half of the Balkan peninsula gathered momentum until, in 279 b.c., the tribe of the Galatae succeeded in sacking Delphi, and, the following year, conquered and settled a large part of Asia Minor. That Celtic civilisation reached a high order is no longer in doubt. Modem research has tended to concentrate upon Celtic achievements in western Europe, but the tribes responsible for the sack of Rome in 390 b.c. and who held sway over large areas of eastern Europe and Asia Minor a century later must similarly have exerted a cultural influence to some extent commensurate with their military strength.

St Paul, writing his epistle from Rome to the ‘ foolish Galatians’, admonishes them for ‘the works of the flesh which are manifest, which are these: adultery, fornication, uncleanness, lasciviousness, idolatry, witchcraft, hatred, variance, emulations, wrath, strife, seditions, heresies, envyings, murders, drunkenness, revellings, and such like ; of the which I tell you before, as I have also told you in time past, that they which do such things shall not inherit the kingdom of God’. [1] St Paul, one feels, might have castigated certain of the contemporary religious and social customs of the pagan western Celts in like terms. The nature and mother goddess worship, fertility cults, belief in magic, sacrifices and orgiastic ceremonies of primitive Celtic religion would not have been easily or quickly lost and evidently the Apostle felt that here was no occasion for mincing words.

St Paul’s strictures notwithstanding, the Celts of Asia Minor and western Europe alike proved particularly receptive to Christianity. Can we assume from this that Christianity echoed some fundamental chord in pagan Celtic religion? We have to admit the possibility, and its consequent pertinence to Illyrian reception of St Paul’s message of Christianity. Nevertheless, we still know too little at present of the Illyrians and the eastern Celts to assess the impact of the latter upon early Christian Macedonia. The powerful influence of Hellenism would have tended to stifle the more obvious Celtic expressions except in the rural, completely Illyrian regions ; but our present ignorance is not necessarily an indication that they were unimportant.

Except in the extreme north-east the Scythians never penetrated, nor in any way dominated the Balkan peninsula. Nevertheless, as powerful northeastern neighbours of the Thracians, with strong cultural and artistic as well as military traditions, their influence could hardly have been negligible.

They were, Tamara Talbot Rice writes, probably an Indo-European people who worshipped the elements.

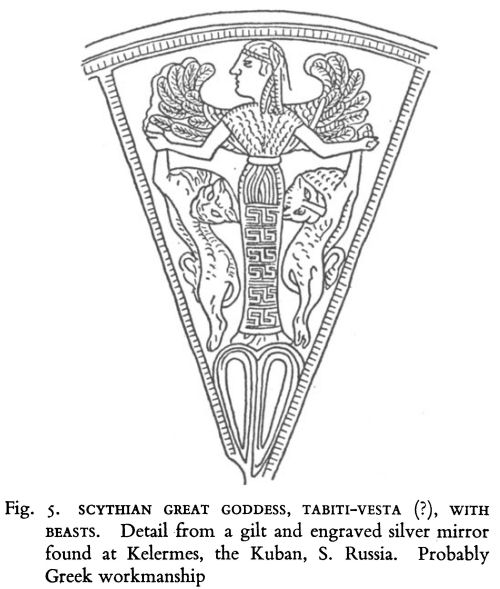

Their main devotions were paid to the Great Goddess, Tabiti-Vesta, the Goddess of Fire and perhaps also of beasts (Fig. 5). She alone figures in their art, presiding at the taking of oaths, administering communion or anointing chieftains. ... In the Crimea, the Great Goddess is not found much before the ninth century B.c., when she is depicted standing, holding a child in her arms, though she did not then represent the goddess of fertility any more than she ever represented a matriarchy to the Scythians. ...

Fig. 5. SCYTHIAN GREAT GODDESS, TABITI-VESTA (?), WITH beasts. Detail from a gilt and engraved silver mirror found at Kelermes, the Kuban, S. Russia. Probably Greek workmanship

1. Galatians v, 19-21.

18

![]()

In Scythian art she sometimes appears as half-woman half-serpent, sometimes standing, sometimes seated between her sacred beasts, the raven and dog, or sometimes with an attendant or in conversation with a chieftain. [1] (Pl. 6c.)

The elaborate manner of their burial of chieftains, in some areas alone, in others together with a favourite wife and attendants, all richly dressed with valuables, accoutrements, food, wine and domestic utensils — lesser warriors enjoyed simpler interments — indicates a belief in some form of after-life. Always horses accompanied the chieftain to his grave, sometimes as few as six or eight, but in the Kuban the number might range from a score to, in one case, around four hundred.

Again lack of knowledge, this time of Thracian customs, prevents us from making any proper assessment of the degree to which they were influenced by these virile nomadic neighbours. Nevertheless, it was probably considerable. It is likely that the Macedonians, Thessalians and Boeotians received the horse from the Thracians who, in turn, had received it from the Scythians. Certainly the Thracian cult of the mounted Heroic Hunter links religious beliefs of Scythia and Greece. In the Christian period it is perhaps possible still to be able to see a reflection of Scythian influence in the zoomorphic carvings on the pillars of the doorway in the chancel screen of the Basilica of St Demetrius (Pl. 26c). Later, a recrudescence of both the Scythian and the Celtic impacts, absorbed and transmuted with much else over the course of hundreds of years into the culture of the Slavs, began in the sixth century. This, however, is beyond the scope of a chapter dealing with Byzantine Macedonia’s legacy from the Alexandrian era.

East and West

It would be wrong to make too clear distinctions between the various influences and their origins that bore upon Macedonia and the Mediterranean world from the Orient. Alexander’s conquests were only one factor in the mixing and syntheses of peoples and ideas which continued as part of the progressive momentum of civilisation. Persia was a composite empire; India variously affected by such different importations as Persian architecture and Persian social policies, Hellenistic art and Scythian rulers; Greeks, Romans, Celts and Armenians were only four of the many racial groups whose varying fortunes were continually changing the cultural complexion of Asia Minor. Persia’s political strength and her ancient civilisations ensured her the dominant position in the Orient, but she both drew from and gave to her neighbours. The political disunity of the Semitic peoples tended to disguise the strength and original nature of their important contributions. Thus although for the sake of simplicity and coherence it is necessary to use such labels as Persian, Indian or Semitic in identifying particular conceptions, it is always essential to remember that the pedigrees of such conceptions were seldom pure and were often extremely mixed.

This point is also important to bear in mind when considering the influence exerted by Antioch and Alexandria. Both were important centres of early Byzantine art, politics, theology, learning and administration. But they were essentially the products of their environments ; and the environments of both included, in constantly varying degrees, each other as well as the whole known world. The early Byzantine world was not static, and the importance of such focal cities as Alexandria and Antioch lay more in their role as markets for the exchange of ideas than as schools of original thought. Although both enjoyed a particular ease of access to certain regions of outside influence, such as Antioch to Persia and Alexandria to India, nothing of importance, except a political attitude, that one of these centres developed, imported or copied was likely to remain its exclusive product for long. Not only were the Greeks themselves always interested in something new, and a common factor in every lively minded city, but the Arabs and Jews were able to penetrate regions closed to Greeks. And they moved, constantly, everywhere, always carrying something, ideas as well as objects, to exchange elsewhere. In such circumstances an article made in Antioch may well have derived jointly, for instance, from Iran, Arabia and northern Mesopotamia, and the history of its particular function and design be ages old.

In contrast to the vigorous and deeply rooted traditions pressing from the East, the end of the second

1. T. Talbot Rice, The Scythians (London, 1957), pp. 85-6.

19

![]()

century a.d. saw the early symptoms of a steady deterioration in the strength of the relatively young Latin West. The Asian provinces of the Roman Empire were protected from the barbarian invaders coming from Central Asia by the natural defences of the Iranian plateau, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasian ranges and the Black Sea. Central, southern and western Europe enjoyed no such geographical advantages. For its defence it could only depend upon its armies, and these had come to bear little resemblance to the disciplined forces which had been responsible for creating the Empire. As early as the end of the second century a.d., the élite legions and even the emperors themselves were no longer of Latin stock, so severe a toll had been taken by the combination of material prosperity and the wastage of the noblest Roman families in continual civil or defensive warfare. Roman tradition, however much of the Greek and Oriental it had absorbed, had still the strength to transfer its unique contribution of law and administration to its Byzantine successor ; yet, even at the time of the change-over, the main burden of this tradition had ceased to be borne by natives of Rome. In the old capital the discipline that had been the foundation of its greatness no longer existed ; with the one all important exception of the small Christian minority. But the concern of these Christians of Rome was with a new and revolutionary future, not with the ancient pagan past.

Yet it would be quite wrong to draw the inference that Rome had a comparatively unimportant share in building the Byzantine Empire. In its imperial phase Rome had been contributing steadily to the social development of its eastern territories and neighbours as well as absorbing much from them. Roman traditions may have gradually depended less and less on natives of Rome itself, but a more important fact was the ability of a Roman emperor to create a New Rome on alien territory, and that from there he and his successors should, for more than a thousand years, continue to govern the Empire of the Romans. That Old Roman forms of religious art and architecture did not maintain themselves in New Rome is not surprising. The old order changed in Old Rome too. The Roman contribution to civilisation was fundamentally civil, not religious. Consequently, the most important of its ‘monuments’ to maintain their position in the Byzantine continuation were achievements in the sphere of law and administration. The fact that these are less easy to picture, are outside the scope of art historians, and less controversial than religious art, must not mislead us as to their importance in forming the social outlook and, thus, indirectly, the art of the Byzantines. The Byzantine Empire rose from the Orient and — not or — Rome, a synthesis created by the culture of Greece.

The Greco-Persian wars, which under one guise or another continued into the Middle Ages until outside forces reduced both protagonists to impotence, were perhaps the most spectacular aspect of the development of the eastern Mediterranean region, but they were not the most important. More fundamental was a common search for a universal religious ideal. In this field Greeks and Persians played the roles of major contributing partners rather than adversaries and Alexander took his place as the ideological successor of Cyrus rather than the military conqueror of Persia.

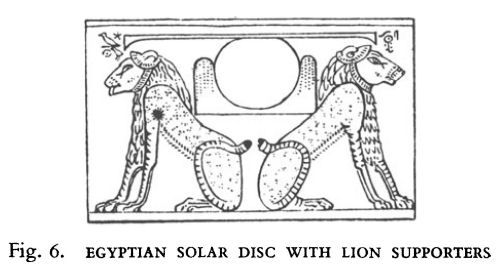

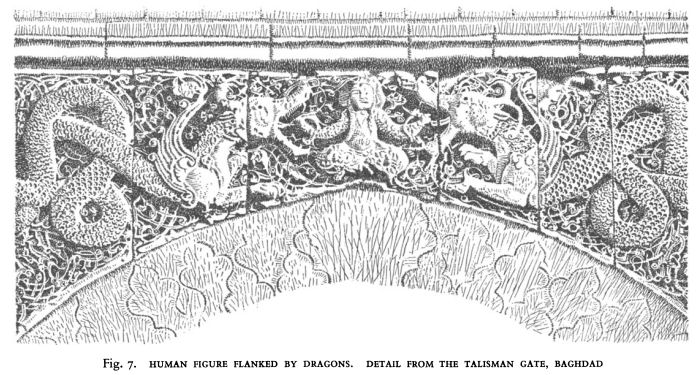

Christianity was the outcome of this common spiritual quest. A new dawn rather than a new world, its deep roots in past ages’ accumulation of religious ideals enabled Christianity to convey its philosophy through the language of symbols which the syncretism of Eastern and Western thought had already given universality. Plates 3 and 4 and Figures 5.7 illustrate the widespread use of one basic aspect of this syncretism, the Great Mother Goddess as the symbol of Man’s belief in Rebirth and Eternal Life. Comparison with examples in Plate 5 indicates, however, a crucial point where, influenced by Hellenism, Christianity broke decisively with its Oriental ancestry. For Christians Death-Eternal Life had ceased to be regarded with dread. The lions or serpents that had guarded Atargatis, Cybele, Lilith and other Asiatic Mother Goddesses were replaced by doves, peacocks, lambs,

Fig. 6. EGYPTIAN SOLAR DISC WITH LION SUPPORTERS

20

![]()

Fig. 7. HUMAN FIGURE FLANKED BY DRAGONS. DETAIL FROM THE TALISMAN GATE, BAGHDAD