PART III. THE MONUMENTS

Chapter X. The Monuments — II : Justinian to the Slav Settlement (527 to Seventh Century)

19. The Basilica B, Philippi 188

20. Country Churches in the Neighbourhood of Caričin Grad 193

(Svinjarica, Kalaja near Radinovac, Ćurline, Prokuplje, Sjarina, Kuršumlija, the Trefoil Chapel outside the southern suburbs of Caričin Grad, Klisura, Sveti Ilija, Sakicol, Trnova Petka, Zlata, Rujkovac)

21. The Basilicas at Lipljan 200

22. The Sixth-Century Foundations of the Holy Virgin of Ljeviša, Prizren 202

23. The Basilica at Suvodol 202

24. The Sixth-Century City of Caričin Grad 204

25. The Episcopal Basilica, Caričin Grad 206

26. The Crypt Basilica, Caričin Grad 209

27. The Cruciform Church, Caričin Grad 211

28. The South-West Basilica, Caričin Grad 213

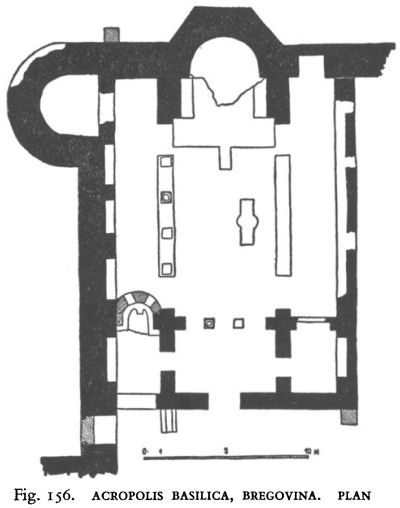

31. The Acropolis Basilica at Bregovina 227

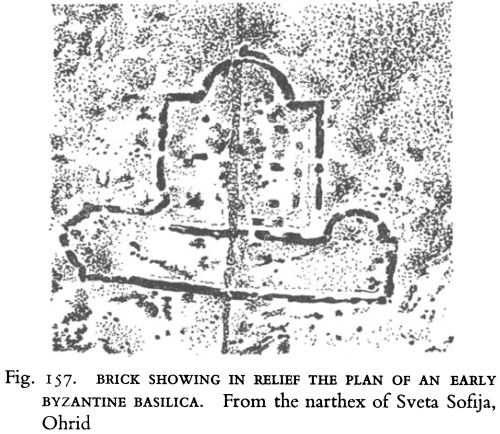

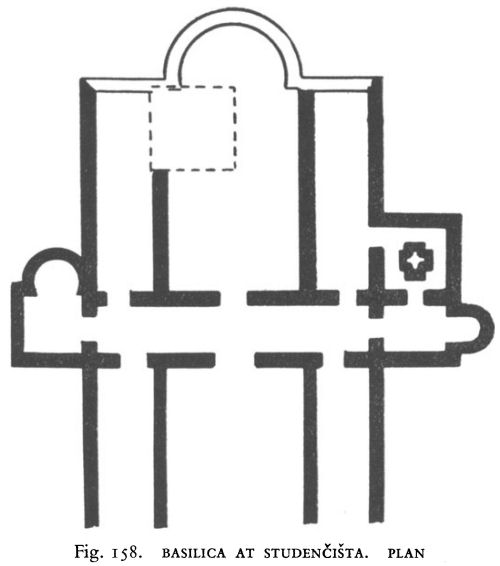

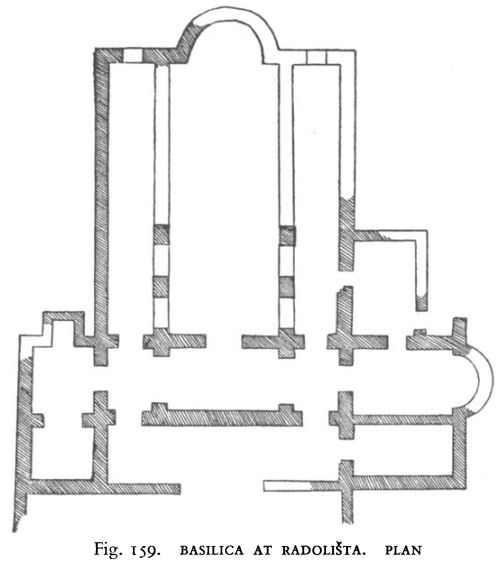

32. Two Basilicas at Ohrid 228

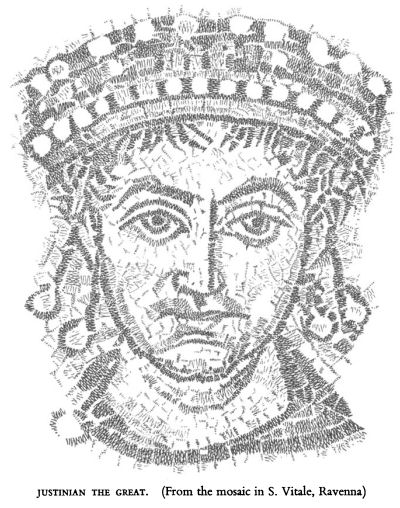

JUSTINIAN THE GREAT. (From the mosaic in S. Vitale, Ravenna)

Chapter X. The Monuments — II : Justinian to the Slav Settlement

(527 to Seventh Century)

Omnia quae cemis magno constructa labore

moenia, templa, domus, fontes, stabula, atria, thermas

auxilio Crristi [sic] paucis construxit in annis

antistes Stefanus sub principe Iustiniano.

All you see around, built with great labour, ramparts, temples, houses, fountains, stables, atria, baths, with the help of Christ has been erected in a few years by the president Stephanus under Emperor Justinian.

(An inscription found at Izbičan near Priboj in Yugoslavia.) [1]

1. N. Vulić, Spomenik, xvciii, 1941-48 (Belgrade), p. 159.

187

![]()

The Gothic wars, the Hun and other invasions had so undermined the economy and reduced the population of the once rich and densely inhabited central Balkan provinces that little construction work of importance beyond the repair of fortifications took place during the seven or eight decades prior to the reign of Justinian (527-65). Under this emperor the fortifications programme was accelerated to meet the new Slav and Avar threat. Procopius tells us that in Thrace, Macedonia, Dardania, Epirus and Greece some six hundred fortified positions were either newly built or, in most cases, strengthened. Regions of particular strategic importance were even provided, where necessary, with new populations and, to meet their requirements, entirely new settlements and even new cities were built with, in the words of Stephanus’s inscription, ‘ramparts, temples, houses, fountains, stables, atria, baths’.

Dardania, including Scupi and Ulpiana, and western Dacia Mediterranea were treated particularly lavishly. For one reason, it was the region of the emperor’s birthplace, a simple village which he transformed into a splendid city with the name of Justiniana Prima. Although definite confirmation is still lacking, it is likely that Justiniana Prima and the archaeological site of Caričin Grad (or Tsarichin Grad to give it an English phonetic spelling) are the same. Certainly the excavations of Caričin Grad have proved the Stephanus inscription to have been no exaggeration.

Apart from possible considerations of sentiment, Justinian had other reasons for this generous building programme. Firstly, the mountains around Caričin Grad were a valuable source of ores. Secondly, with the breaching of the frontier defences along the Danube and Save rivers by great numbers of Slavs, Avars and other land and plunder hungry peoples, it had become a key region in the new defence in depth among the Balkan mountain ranges, a defence system which Deroko and Radojčić describe as ‘by the extent and variety of its construction among the greatest works of its kind in world history’. [1]

Caričin Grad and the impressive numbers of religious, civil and military buildings of which evidence is being discovered in its neighbourhood all owed their existence to the new circumstances of the sixth century. Wars and invasions had not been the only disasters to have befallen the Balkans. Earthquakes, and doubtless pestilence, had added their toll. A severe earthquake in 518 had reduced Scupi to ruins, and at the same time Stobi and other cities must have suffered considerable damage. But now the Balkans faced the prospect of barbarian invasion and chaos beside which the Gothic depredations must have appeared minor disturbances. The Vardar valley, and such cities as Stobi and Scupi, lost not only their military and commercial raison d’être but also their security, for Balkan defences were now centred upon and directed from Constantinople, not Thessalonica, and the Vardar had consequently been transformed from an imperial artery into a natural route for invaders.

Dangerous as it is to draw conclusions from incomplete evidence, our present knowledge of buildings erected in the sixth and seventh centuries testifies impressively to the paramountcy of military considerations and the high rating accorded to the Christian religion as an imperial asset. Churches were built profusely in the militarily strategic areas. Elsewhere even major restorations seem to have been an exception. The morale of the citizens in the face of constant danger is the only rational explanation of the rebuilding of St Demetrius in the seventh century. The replacement of Basilica A at Philippi by a new episcopal church towards the middle of the sixth century is the only example of which we know where a new Justinian church in Macedonia probably possessed a civil, to be precise, a pilgrimage, significance, rather than one that was primarily military. It may, therefore, be useful to discuss it first and then to take a group of country churches in the north, where new influences make their appearance from other parts of the Byzantine Empire.

19. THE BASILICA B, PHILIPPI (Pls. 53-55)

The site chosen by the Philippians for a replacement of Basilica A lay to the south of the Via Egnatia and, unlike the earlier church, was a distance of several hundred metres from the Acropolis.

1. A. Deroko and S. Radojčić, ‘Byzantine Archaeological Remains in the Region of Jablanica and Pusta Reka’, Starinar, 1950, pp. 175-81 (Belgrade) (Serbian).

188

![]()

Fig. 97. BASILICA B, PHILIPPI. PLAN

Fig. 98. BASILICA B, PHILIPPI. Section. (Reconstruction after Lemerle)

A group of Roman buildings was levelled in order to construct a domed basilica with eastern annexes that, of comparable size (56 metres in length including the narthex and the apse), was more complex and no less splendidly and excitingly conceived than its predecessor. [1] Nevertheless, it was even more ill-fated. Before the sanctuary and atrium had been completed, the great dome that had been raised above the former collapsed.

1. P. Lemerle, Philippes et la Macédoine Orientale (Paris, 1945), pp. 415-513.

189

![]()

Thereupon work ceased, and the church remained in its shattered and unfinished state. Probably all available financial resources were exhausted, and the circumstances of increasing insecurity and economic disruption were not conducive to the investment of huge stuns upon the building and repair of elaborate pilgrim churches.

Basilica B was built of stone and brick ; stone for such principal structural members as the piers, brick and stone in alternating series of rubble filled courses for the walls, and brick for the vaults.

Three entrances led from the eastern portico of the atrium into the narthex, nearly 31 metres across and 7.50 deep. Its north and south walls also contained doorways. A second, symmetrically placed set of three arched entrances opened from the narthex into the nave and the two aisles. The central opening, which was slightly larger than the others, did not have a tribelon. Both nave and aisles were short, less than 19 metres, and relatively wide, 15*40 and 6*40 metres respectively. As Lemerle points out, if the width of the low, single stylobate dividing nave and aisle is added to that of the latter, the proportion is just 2:1. The nave and aisles terminated at two massive piers, and here the colonnades tinned outwards to meet the north and south walls and to enclose the aisles. The ambo stood in the middle of the nave at its eastern end.

East of the two piers, which with two others standing at each side of the apse carried the church’s great, single, eastern dome, was a large rectangular space, 14 metres deep, 31 across and bounded by the northern, eastern and southern walls of the main body of the structure. In the centre of this space, directly underneath the dome, was the bema, its altar, covered by a ciborium, standing between two opposed presbytery benches. A low chancel screen extended westwards from these benches, but turned inwards to form a central entrance while still beneath the dome. A slightly horseshoe-shaped apse, with three windows and with two substantial buttresses besides the two eastern piers at its base, protruded beyond the east wall.

Two narrow rooms, with small eastern apses that jutted beyond the east wall on either side of the main apse, were annexed in symmetrical fashion to the north and south walls of the rectangular space containing the bema. They were connected to this part of the church by doorways at the western ends of the intervening walls. West of and lying flush with these two rooms were two others, that on the southern side being somewhat longer than the northern room. The latter was the baptistery, and contained a rectangular baptismal basin in its centre. Both rooms had doorways leading to those with apses, to the aisles and to the outside. Unlike the rest of the structure all four of these annexed rooms lacked a second storey and, from the structural viewpoint, therefore, cannot be regarded as forming a true transept.

The nave, Lemerle considers, was probably vaulted with clerestory fighting, and vaulting was also used for the aisles and narthex and for the galleries which ran above them. The dome, resting upon pendentives, was ht by windows inserted along its base.

Like Basilica A, the internal decoration of Basilica B was of a particularly high artistic standard that probably reflected the influence of Constantinople rather than Thessalonica. In Lemerle’s words, the decoration is, ‘in effect, that of Aghia Sophia, carried into the heart of Macedonia by an artist himself from Constantinople’, and ‘the clearest evidence we possess of the expansion into the provinces of the decorative style created in Aghia Sophia, and, on the other hand, of the close dependence on the capital by Macedonia at that time’. [1] (It should be noted, of course, that Lemerle was speaking specifically of eastern Macedonia.)

Coloured marble was featured more freely than in Basilica A. Green Thessalian marble was used for the columns of the nave and in the bema ; white marble in the galleries. The capitals of the nave were of exceptional beauty, and as modem in relation to those of Basilica A as was the church itself. Their main decoration, appearing on each of the four faces, consisted of two large, thorny acanthus leaves, carved in sharp relief to utilise with maximum effect the contrast of light and shade. Sculptured in local marble, they nevertheless closely followed the designs of capitals in Aghia Sophia in Constantinople.

1. P. Lemerle, op. cit. p. 513.

190

![]()

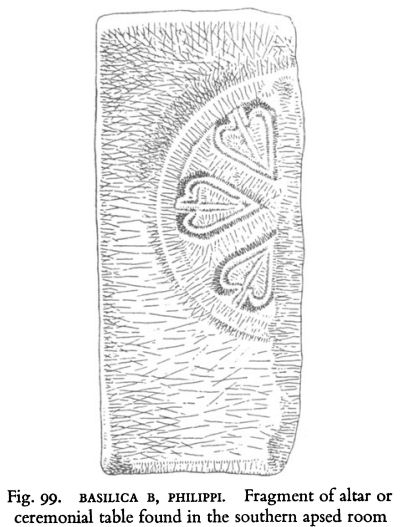

Fig. 99. BASILICA B, PHILIPPl. Fragment of altar or ceremonial table found in the southern apsed room

Their imposts, carrying an ornamental band of reliefs of stylised, joined fishes, recall the crossed fish motif which is a characteristic of the mid-fifth-century church of Alahan Kilisse (Koja Kilisse) in Cilicia. The same motif is also to be seen in an ornamental band on the remains of the north-west pier and a short piece has similarly survived on the east interior wall of the narthex.

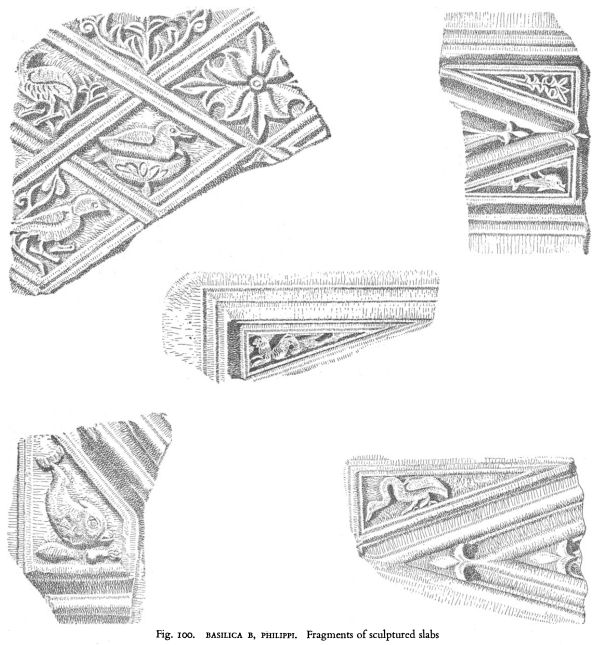

A fragment of a slab, apparently belonging either to an altar or to a prothesis table, has been found with a carving of an encircled six-armed cross formed from six stylised ivy leaves. This motif, flanked by two four-armed crosses over single ivy leaves, is to be seen again on part of a chancel slab, where its execution closely resembles that on the chancel slab of the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica (Pl. 10 h).The inside face of this fragment displays a circle or medallion enclosing a normal four-armed cross. A number of small pieces have survived from other types of slabs, some clearly belonging to the ambo, others to the parapets of the galleries and, possibly, to the chancel screen. Most of these are fragments of the type of slab either displaying a diamond shape inscribed within a rectangle, the central and corner spaces being filled with various symbols of Christian significance, or characterised by a series of small diamond outlines, each containing a bird or a foliate design (Fig. 100).

The transitional and experimental nature of Basilica B is reflected in the arrangement of the sanctuary which not only comprised the whole of the large rectangular space at the eastern end of the church and the apse extending east of the bema, but also the two apsed north and south annexes, which, it seems, were constructed to serve the functions of prothesis and diaconicon. The absence of a tribelon, and the position of the ambo, exactly in line with the entrance from the narthex into the nave and the entrance through the chancel screen into the bema, imply a fundamental change from the liturgical plan followed in Basilica A. There, provision was made for ceremonial processions to pass from the narthex, through the tribelon, along the centre of the nave into the bema. The plan of Basilica B ruled out the practicability of such a procession, in spite of the fact that the sixth century, its date of construction, was a period of greatly increasing ceremonialisation.

Here, perhaps, we have the explanation of the spaces between the bema and the prothesis and diaconicon annexes. Although receptive to Syrian influences, Philippi had remained essentially a Greco-Roman city. Syrian influence had resulted in the introduction of a simple form of tripartite sanctuary in Basilica A ; the later church, as one would expect from its position and importance as a pilgrimage centre, made appropriate provision for such officially recognised liturgical changes — all of them in the direction of the consolidation of this Syrian influence — as had occurred in the interval. Nevertheless, the Greco-Roman nature of Philippi, while conceding the necessity for chambers of prothesis and diaconicon, retained its native form of bema, one, in fact, almost identical to that of Basilica A. Not only did this leave the altar in full view of the congregation in the nave, it provided, as had Basilica A, open spaces accessible alike to the bema and the nave for the deacons to perform their offices. The plan of the sanctuary of Basilica B was a stage in the transformation of the Greek church from its original basilical form into the domed, ‘ cross-in-square ’ building. It was an important stage, moreover, for despite the disaster in which this Greco-Syrian compromise ended, it was repeated,

191

![]()

Fig. 100. BASILICA B, PHILIPPl. Fragments of sculptured slabs

although without the complication of a dome, in the seventh-century reconstruction of the Basilica of St Demetrius in Thessalonica, as can be seen from a comparison of the plan of the sanctuary with that shown in Figure 66.

The style of Basilica B’s decoration and architecture indicates a date of construction slightly earlier than that of Aghia Sophia in Constantinople, dedicated in 563. This is supported by the liturgical arrangements, and a date towards the end of the first half of the sixth century is likely to be correct.

The subsequent history of Basilica B is shrouded in the same dismal oblivion that overtook the rest of Philippi.

192

![]()

For two or three centuries and possibly longer it seems to have remained an unconsecrated ruin, for most of the period lying in the middle of a sacked and desolate city. Later, perhaps around the tenth or eleventh centuries, the apsed annexes and the narthex appear to have been adapted for use as small chapels. The church’s sole inscription, found in the nave and dated to 837, was carved by a Bulgar hand. In a cryptically ominous manner its concluding words supply a grim postscript — almost, one might say, an epitaph — to the Early Byzantine history of the once proud city of apostolic fame. It reads:

‘If one seeks the truth, the god sees it, and if one deceives, the god sees it. The Bulgars have done much good to the Christians, and the Christians have forgotten it; but the god sees it.’

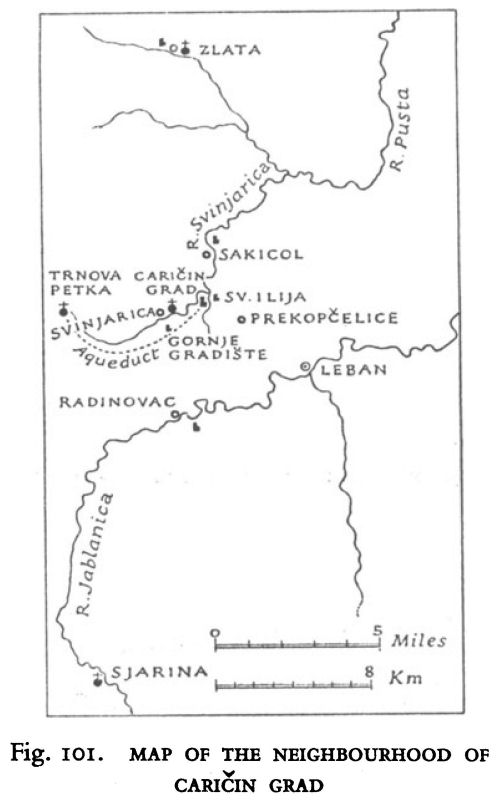

Fig. 101. MAP OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF CARIČIN GRAD

20. COUNTRY CHURCHES IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF CARIČIN GRAD

Many years must pass before a sufficient number of the churches built around Caričin Grad in the sixth century have been excavated and analysed to enable a definitive account of them to be given. Nevertheless, the various ruined churches so far discovered have each a particular historic value in the sense that they were local buildings, built by and designed for local congregations.

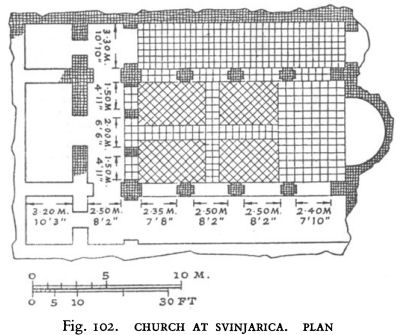

Fig. 102. CHURCH AT SVINJARICA. PLAN

Three different types have been identified as dating from the sixth century : basilical, cruciform and single naved. The church at Svinjarica (Fig. 102) is a basilica with a nave and two aisles, one, possibly more protruding apses, rounded inside but with a three-sided exterior, a narthex and an exonarthex. The exonarthex, of which little has survived, is divided into three parts, corresponding to the nave and aisles, and Petković, who excavated it, remarks that it probably comprised two towers flanking a portico. A tribelon connects the narthex and the nave and there are no signs of a closed sanctuary or of parabemata. Brick was used for the walls and for the piers lining the nave. These piers present a cruciform shape through having pilasters on each of their four sides.

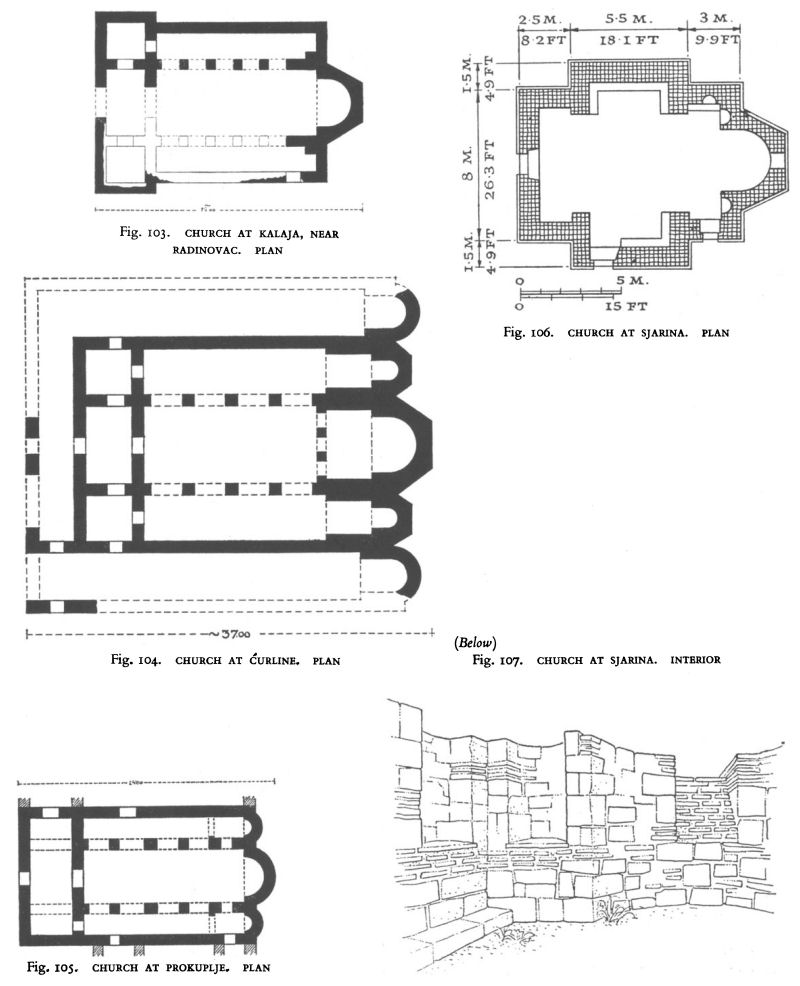

A basilica with a nave and two aisles has also been found at Kalaja near Radinovac (Fig. 103). Its single apse is rounded inside with a three-sided exterior.

The lines of columns end in walls projecting from each side of the apse, giving the impression of side chambers at the eastern ends of the aisles similar to the ‘Synagogue’ Church at Stobi. No exonarthex has been revealed, but the narthex is almost identical in its ground plan with the exonarthex of the basilica at Svinjarica and probably also consisted of a towered portico.

193

![]()

Fig. 103. CHURCH AT KALAJA, NEAR RADINOVAC. PLAN

Fig. 104. CHURCH AT ĆURLINE. PLAN

Fig. 105. CHURCH AT PROKUPLJE. PLAN

Fig. 106. CHURCH AT SJARINA. PLAN

Fig. 107. CHURCH AT SJARINA. INTERIOR

194

![]()

These two basilicas can be compared with two others situated farther to the north, the churches of Ćurline (Fig. 104) and Prokuplje (Fig. 105),belonging to the Naissus complex of fortified centres. Both of them are triple apsed. Both have clear indications of parabemata. In Curline these are particularly marked, and in this church the bema, moreover, is separated from the nave by two substantial pillars. The ground plans of the narthices of both churches closely resemble that of Kalaja, but although both have a single central western entrance it is difficult to judge whether they may be considered as twin towered structures flanking single porticoes. The church at Prokuplje does not appear to have an entrance from the northern section of the narthex into the corresponding aisle.

Two types of cruciform church are found in this area. The first is represented by the small church of Sjarina (Figs. 106,107). This is in the form of a free cross with squat north and south arms that project only a metre and a half beyond the walls of the nave. A single, protruding eastern apse has a rounded interior and a three-sided exterior. Pilaster-like projections extending into the nave from the north and south arms give an impression, enhanced by the presence of three doorways, of a definite division into narthex, nave and sanctuary.

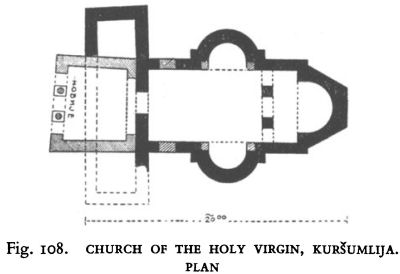

Fig. 108. CHURCH OF THE HOLY VIRGIN, KURŠUMLIJA. PLAN

The second cruciform type is a trefoil. One occurs at Kuršumlija in the Church of the Holy Virgin (Fig. 108), another a short distance beyond the southern suburbs of Carion Grad (Fig. 109), and a third at Klisura (Fig. 111). The first two are identical in plan. Both have projecting eastern apses that are rounded inside but three-sided on the exterior, and two others, rounded inside and out, which jut from the middle of the north and south walls. The arrangement of the narthex of the church at Kuršumlija, which was rebuilt in the twelfth century, is not entirely clear, but all available evidence points towards its construction on lines closely similar to that near Caričin Grad, which was excavated by Mano-Zisi a few years ago, and the ground plan of which indicates two rooms jutting north and south of the walls of the nave and enclosing a portico leading from an atrium into the church.

Fig. 109. TREFOIL CHAPEL OUTSIDE THE SOUTHERN SUBURBS OF CARIČIN GRAD. PLAN

195

![]()

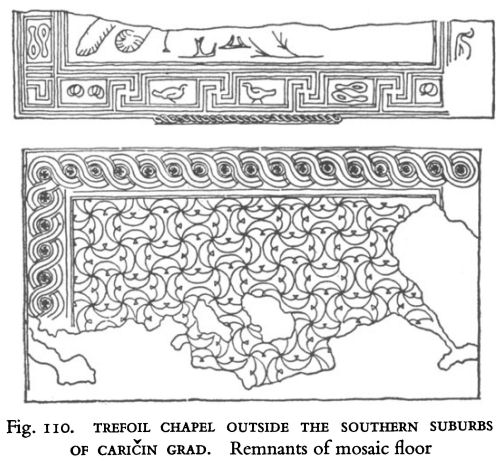

Fig. 110. TREFOIL CHAPEL OUTSIDE THE SOUTHERN SUBURBS OF CARIČIN GRAD. Remnants of mosaic floor

In both churches foundations of chancel screens indicate that the eastern arm of the cross was marked off to be the sanctuary and in each church a tomb was discovered in the south apse. In the church near Caričin Grad portions of decoration have also survived including some of the mosaic floor of the narthex portico. Similar patterns appear in the Baptistery and in the South Church of Caričin Grad. A small section of mosaic floor was also found on the south side of the nave. The border repeats the design of the outer parts of the South Church nave’s central strip and, from the remaining fragments of mosaic within the border, Mano-Zisi has reconstructed a composition of two peacocks on each side of a vase, from which springs a vine [1] (Fig. 110).

The excavations revealed that mosaics and wall paintings were both used on the walls of the nave, but it appears that the latter replaced the former after the original construction of the church.

Two Ionic-impost capitals, similar to some of those from the South Church, have also been found. Other sculptured remains include fragments of the chancel screen and a Corinthian pilaster capital with what are described as elongated forms of acanthus leaves.

The tomb in the south apse, the rich decoration occurring in such a relatively small building, and its situation a short distance beyond the limits of Caričin Grad’s suburbs, give the impression that this church may have been a private memorial chapel belonging to a wealthy provincial official or landowner. One can imagine it originally standing in the grounds of a large estate, with the spacious and comfortable country mansion of the proprietor close at hand. Unfortunately, such a position was vulnerable in the event of a raid on a large enough scale to force the garrisons into their fortified strongholds while the countryside around was looted and set in flames. It is easy to appreciate that when it was possible to restore the chapel, this had to be done on a more modest scale. Even so, the colours of the paintings on the walls had no time to lose their freshness before they, too, were tumbled to ruin.

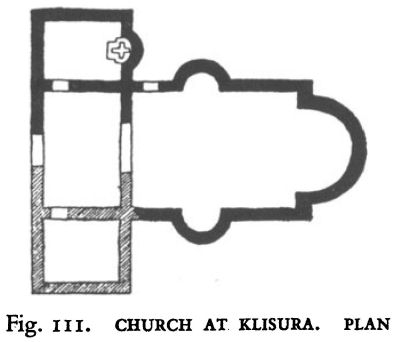

The third example of a trefoil plan, at Klisura, follows closely similar lines. The principal difference lies in the fact that the lateral apses are here smaller in relation to the large eastern apse, which is rounded inside and out. The church has been less thoroughly excavated than the trefoils at Kuršumlija and near Caričin Grad, but it appears to possess the same form of narthex with side chambers jutting north and south of the walls of the nave. At Klisura, however, unlike its two sister churches, the northern chamber is apsed. A small cruciform honephterion has been found in this apse, indicating that the chamber served a prothesis purpose. [2] The presumed southern chamber has not been verified by excavation.

Fig. 111. CHURCH AT KLISURA. PLAN

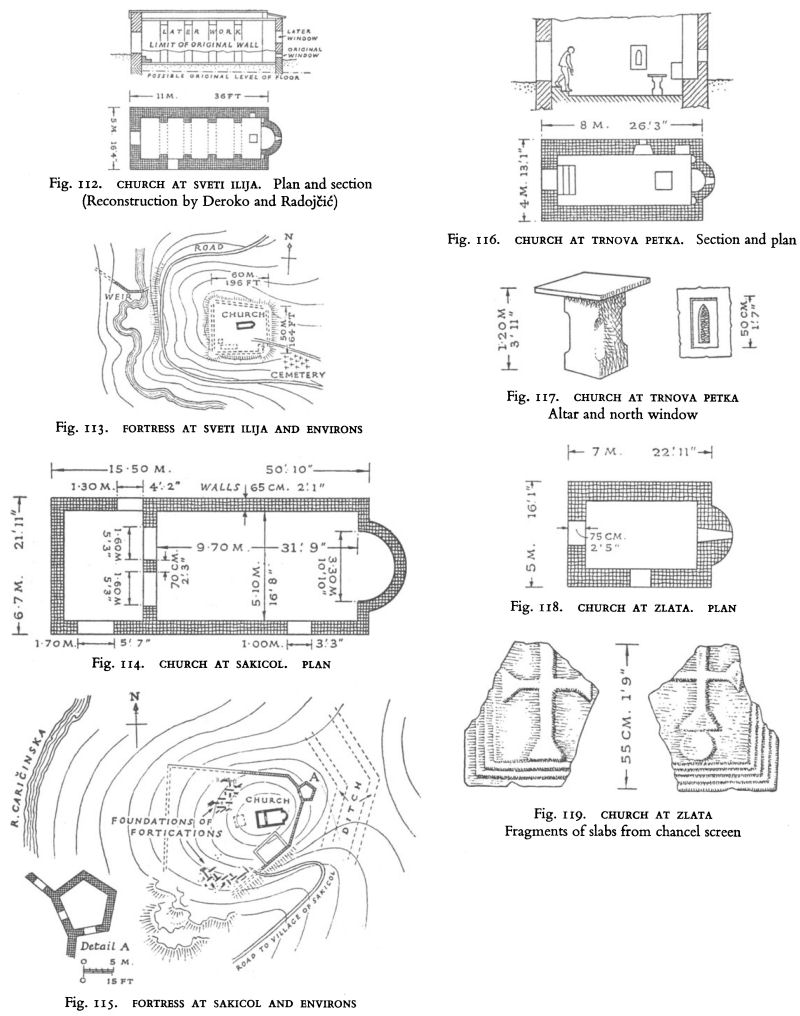

At least five single-naved churches belonging to the sixth century have been excavated in the locality : at Sveti Ilija (Figs. 112, 113) sited on a fortified hillock on the outskirts of Caričin Grad, at Sakicol (Figs. 114, 115),

1. G. Mano-Zisi, ‘The Excavations of Caričin Grad, 1949-52’, Starinar, 1952-53, pp. 154-6 (Serbian).

2. G. Stričević, ‘The Diaconicon and Prothesis in Early Christian Churches’, Starinar, 1958-59, pp. 60-6 (Serbian).

196

![]()

Fig. 112. CHURCH AT SVETI ILIJA. Plan and section (Reconstruction by Deroko and Radojčić)

Fig. 113. FORTRESS AT SVETI ILIJA AND ENVIRONS

Fig. 114. CHURCH AT SARICOL. PLAN

Fig. 115. FORTRESS AT SARICOL AND ENVIRONS

Fig. 116. CHURCH AT TRNOVA PETKA. Section and plan

Fig. 117. CHURCH AT TRNOVA PETKA. Altar and north window

Fig. 118. CHURCH AT ZLATA. PLAN

Fig. 119. CHURCH AT ZLATA. Fragments of slabs from chancel screen

another fortress a short distance to the north, at Trnova Petka (Figs. 116, 117), whence an aqueduct carried water to Caričin Grad 10 kilometres away, at Zlata (Figs. 118,119) and at Rujkovac (Fig. 120). The first four of these small churches were simply constructed buildings with single, protruding apses, rounded inside and out.

197

![]()

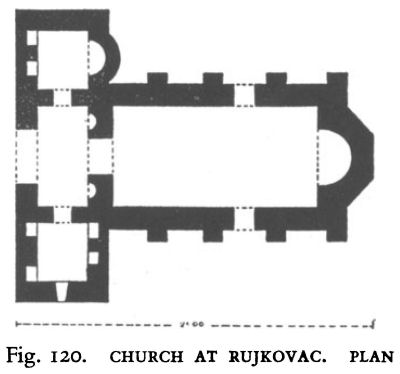

Fig. 120. CHURCH AT RUJKOVAC. PLAN

From the pilaster-like projections appearing on the plan of Sveti Ilija it seems likely that the roof of at least this church may have been barrel-vaulted. Their small dimensions and their situations make it reasonable to assume that, with the possible exception of the church at Zlata, which was a city of considerable size that still awaits excavation, these are examples of chapels erected to serve the garrisons of the local forts.

The church at Rujkovac is distinguished from the others by its exterior buttressing of the walls of the nave, probably to support a barrel-vault, by its apse, which has a three-sided exterior, and by its narthex, from which two rooms project north and south of the main body of the church. The northern of these two rooms has an eastern apse, rounded inside and out. The ground plan revealed by the excavations indicates the likelihood of another example — this time attached to a single-naved basilica — of a western portico flanked by twin towers.

These churches bear little relationship to the Macedonian monuments we have been considering hitherto. That they lay on the extreme northern periphery of Hellenism, or even just beyond it, where Hellenic influences of earlier times had never succeeded in penetrating deeply, is not an explanation of such fundamental differences. For two centuries or more prior to the middle of the fifth, Thessalonica had been the cultural and artistic capital of Illyricum from the Aegean to the Danube. Then its influence had retracted in the face of the invasions, devastations and depopulation of the second half of the fifth century, and Justinian’s policy of centralisation of administrative power in Constantinople was not conducive to its restoration. Nor, in view of the Macedonian city’s record of obstinate opposition to the imperial capital, did it have any particularly persuasive claim for preferential support from a strong emperor.

In order to defend the Balkan approaches to the capital Justinian needed to dispose large numbers of troops and supporting services as settled garrisons. The Illyrian reservoir of military manpower, which had long stocked the armies of the Roman Empire, was now empty, in a large degree a consequence of the wars on Rome’s distant Asiatic frontiers. Fortunately, a new reservoir was now available in Anatolia, the inhabitants of which shared many characteristics with those of the central Balkans.

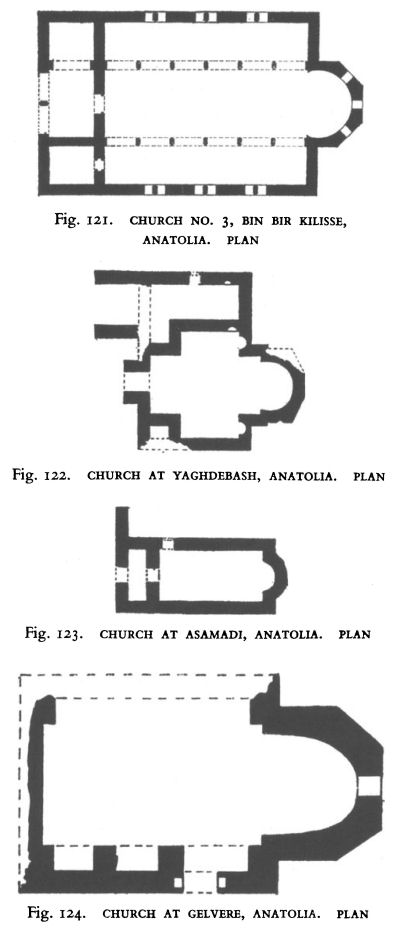

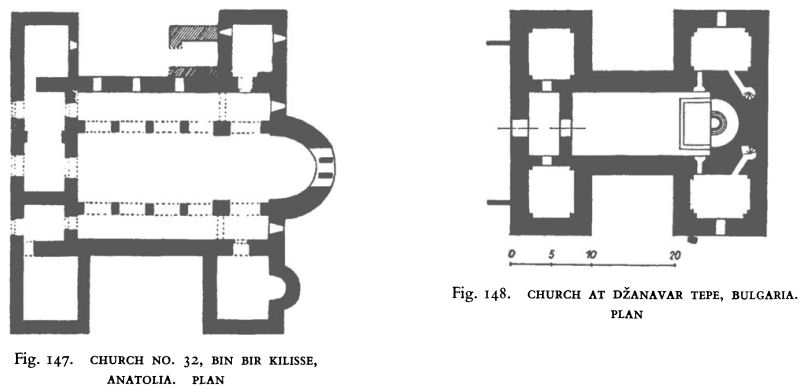

In these circumstances, it is not surprising that we can find in Anatolia numerous prototypes of the small churches that have been excavated around Caričin Grad, and the relationship is all the more striking in that it has of necessity been for the most part translated from stone into brick. The towered portico is, in fact, none other than the ‘Hilani’ narthex, inherited by the Christians of eastern Asia Minor, northern Syria and northern Mesopotamia from the ancient Hittites. The single, protruding apse, rounded inside and polygonal outside was one of the common Anatolian forms. The cruciform or double piers or columns used for springing powerful arches in, for instance, Churches 1, 3, 4, 5, 15, 21, 25 and others around Bin Bir Kilisse in eastern Lycaonia are reflected in the nave colonnades at Svinjarica.

As an example of the central Anatolian basilica, Church No. 3 of Bin Bir Kilisse (Fig. 121) may be cited. Yaghdebash (Fig. 122) or Süt Kilisse, from the same neighbourhood can be compared with the cruciform church of Sjarina. A variety of single-naved churches have also been identified in the same region, both with and without narthices, as, for example, at Asamadi (Fig. 123) and Gelvere (Fig. 124). Such a simple form was not, however, specifically Anatolian, and the ground-plan without other evidence, such as the ‘Hilani’ narthex, is therefore insufficient to adduce its origins.

The trefoil plan, on the other hand, does not appear to be a form native to Anatolia, where it occurs but rarely. Gertrude Bell, analysing the views of various writers on the subject, concludes that a trefoil apse appears in Asiatic palaces probably as early as the time

198

![]()

of Solomon and that as a church form it is essentially memorial. [1] In palace architecture the trefoil maintained its popularity in Syria, where we know it to have been used in the early sixth-century Episcopal Palace at Bosra and in the eighth-century palace of M’shatta, which was built by a Moslem Caliph. The Holy Land has been considered the probable site of its first application to Christianity, [2] but at the same time and probably earlier it was certainly used for pagan funerary purposes in Italy and in Syria. [3] Its popularity as a form of Christian architecture spread rapidly during the fourth and fifth centuries. Examples such as the Palestinian churches at Ras Siagha on Mount Nebo, of St Theodosius at Deir Dosy and the foundations of a church at Taiyiba ; as the Egyptian churches of the Red and White Monasteries at Sohag (circa 440) and the fifth-century church at Dendera ; as Tebessa in Algeria; as the celiae trichorae at Sirmium and at Buda and Savaria (Szombathely) in Pannonia; and as S. Symphoroso and the East and West Chapels in the Cemetery of Callixtus in Rome, serve to show its wide geographical distribution. Justinian’s reconstruction of the sanctuary of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem followed a similar form. About the same time it was used in Bulgaria at Peruštica and in western Greece at Dodona and Paramythia. In Provence, the trefoil chapel on the island of St Honorat was probably built in the seventh century under the influence of Egyptian monasticism.

Fig. 121. CHURCH NO. 3, BIN BIR KILISSE, ANATOLIA. PLAN

Fig. 122. CHURCH AT YAGHDEBASH, ANATOLIA. PLAN

Fig. 123. CHURCH AT ASAMADI, ANATOLIA. PLAN

Fig. 124. CHURCH AT GELVERE, ANATOLIA. PLAN

These few examples are sufficient to establish that by the sixth century the trefoil form had come to enjoy a very considerable degree of prestige in the Byzantine sector of Christianity, and that an important factor in this prestige may have been original associations with the Holy Land and, less consciously perhaps, Persian concepts of divine kingship.

In the first centuries of Christianity, the terms ‘martyr’ or ‘witness’ seem to have been used for all those who, whenever they lived, witnessed to the divinity of Christ. Possibly at one time they denoted only those who had been associated with Christ on earth, but by the Peace of the Church the meaning seems likely to have included the Virgin and the Prophets, although it was applied particularly to those who before dying for their Faith were favoured with a direct contact with God. Thus a ‘martyrion’ as used in the time of Eusebius was a monument erected at a place of witness, not necessarily upon the site of the death or burial of one who had died in the persecutions.

1. W. Ramsay and G. L. Bell, The Thousand and One Churches (London, 1909), pp. 340-6.

2. E. H. Freshfield, Cellae Trichorae (London, 1918), vol. II, p. 33.

3. A. Grabar, Martyrium (Paris, 1946), vol. I, p. 113 et seq.

199

![]()

Against this background it is easy to see that in a Western Asian and Imperial Roman environment such as the Holy Land, the architectural form appropriate to a place sanctified by witness to Christ should be modelled upon the Oriental throne-room where sat the divinely appointed king-emperor. Hence, the trefoil, additionally hallowed by the fact that in sacred arithmetic the figure three, the number of the Trinity, represented the soul, developed within the Early Byzantine sector of Christianity as a form suitable for either a baptistery or a funerary chapel. As a baptistery it was, in the most literal sense, a place of witness, as well as symbolic of the resurrection to come, even to the extent of the three-figure grouping that had immemorially represented the Source of Eternal Life (Pls. 3.5 and Figs· 5.9). As a funerary chapel, the trefoil resurrection symbol was equally appropriate, and its association with the burials of the large number of saints put to death in the final great persecution made it a particularly favoured form for a private memorial chapel of an eminent or wealthy person. We must, therefore, class the trefoil church near Caričin Grad, and its sister churches of Kuršumlija and Klisura, as quite distinct in origin and purpose from the garrison churches erected by and for the troops and civilian settlers from Anatolia. The civil officials and local landowners came either from Constantinople or, in a few cases perhaps, from Macedonian and Dardanian families who had been wealthy before the troubles and had managed in some way or other to retain their properties or connections. Such people would affect the fashions of the capital and the court, certainly not those of another, more remote provincial region.

Finally, we should note the subsequent development of this trefoil form into a popular style of later Balkan church architecture. A new church was reconstructed upon the ruins of Kuršumlija in the twelfth century. What was its relationship to many of the Raška and Morava churches, to the numerous trefoil churches from Vatopedi, Iviron and Hilandar on Mount Athos to Curtea de Arges in Wallachia and Humor and Voronets in Moldavia ? The answers to these questions are far from simple and are, in any case, outside the scope of this book, but the contribution made by Kuršumlija and its sister churches to the persistence of this particular form in the Balkans may be considerable.

The whole neighbourhood of Caričin Grad, which was only one of many points in the defence network of the central Balkans, teems with archaeological possibilities awaiting excavation. To mention but one instance, at Zlata, a short distance to the north-west and where a tiny chapel and sculptured furnishings from an early Byzantine church have been discovered, a city complex has been traced which Deroko and Radojčić describe as ‘a big fortified city, larger than Caričin Grad’. It may even be that Zlata, and not Caričin Grad, was Justinian’s foundation of Justiniana Prima.

21. THE BASILICAS AT LIPLJAN

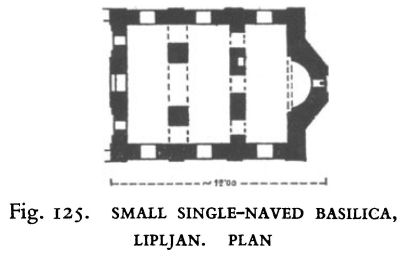

From the archaeological viewpoint, the remoteness of the Caričin Grad region has been fortunate. Other centres which might have proved as rich, or almost as rich, instead of their ruins being left to decay undisturbed further by man, have been to a greater or lesser extent built over in subsequent periods. One such was Ulpiana (Lipljan), a Dardanian city which was renamed by Justinian ‘Justiniana Secunda’. Here tradition associates a small, single-naved, thirteenth-century church with a fourth-century foundation built to commemorate two local martyrs killed during Diocletian’s persecution. Although it is difficult to tell whether these foundations do actually date from the fourth century, certainly they are not later than the sixth. [1]

Fig. 125. SMALL SINGLE-NAVED BASILICA, LIPLJAN. PLAN

Since a beginning was made in 1953, considerable progress has been accomplished in excavating parts of the ancient city.

1. I. M. Zdravković, ‘The Ancient Church of Lipljan’, Starinar, 1952-53, pp. 186-9 (Serbian).

200

![]()

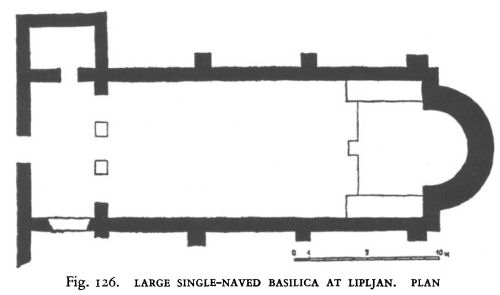

Fig. 126. LARGE SINGLE-NAVED BASILICA AT LIPLJAN. PLAN

In 1956, following reconnaissance by aerial photography, the foundations of the greater part of a single-naved basilica, 34 metres long and 14 wide, were uncovered. [1] The building possessed a massive rounded apse. Presbytery seats were ranged opposite each other. Two floor layers were observed in the sanctuary, which also contained a small crypt and a marble altar that had earlier belonged to a Roman building. The floor of the nave and the lower floor of the sanctuary, both of which were at the same level, were composed of mortar and crushed brick. The later and higher floor of the sanctuary, however, was covered with mosaic.

A tribelon, its two pillars of serpentine marble standing on stone bases, connected the nave with a narthex, paved with bricks and of the same width as the nave. The single western entrance of the narthex used as its threshold a Roman marble tombstone. To the north and south of the narthex doorways opened into small rooms jutting beyond the nave walls.

The walls of the church, as far as can be seen, were of rubble bound with brick courses. The north and south walls were each strengthened by three buttresses, possibly with the object of supporting a barrel-vault. The excavators draw attention to two doorways, situated just to the west of the sanctuary, and point out that the excavation programme of 1956 did not allow them to investigate the possibility of their leading to prothesis and diaconicon chambers. However, in view of the sanctuary arrangements and the smallness of the doorways, this appears unlikely.

Except for the shape of the outer apse, certain details of the two chambers of the narthex, the southern of which had not been fully excavated, and the tribelon, this Ulpiana basilica closely resembles that at Rujkovac, near Caričin Grad. Clearly we have here yet one more Balkan version of the Anatolian ‘Hilani’ narthex. Its unusual association with a tribelon is probably significant of the greater degree of Hellenistic cultural influence which would have existed in this more southerly and long-established city. Like that at Rujkovac, this church can be dated to about the middle of the sixth century.

Excavations conducted in the ancient necropolis have also yielded evidence of at least two other important buildings connected with a religious purpose. Both appear to have been Christian basilicas, and both bear the signs of several building phases corresponding to different periods in the city’s history.

One of these basilicas, the excavators report, was built above a number of existing tombs. Its last building phase, to which the greater part of the structure belongs and which they date to the second half of the sixth century, is remarkable for the diverse types of masonry piers dividing the nave from the aisles and for the unequal level of the excavated floor. Beneath the nave floor were found tombs of various kinds, including ordinary burials, simple brick constructions, large tombs formed of stone slabs, and re-used sarcophagi. One tomb contained a skeleton buried after the Germanic manner of interment in a wooden chest.

In spite of a careful search the form of the apse could not be ascertained, tomb robbers having completely destroyed it at some earlier date.

1. I. Popović and E. Čerškov, ‘Ulpiana, A Preliminary Report on Archaeological Research from 1954 to 1956’, Glasnik Muzeja Kosova i Metohije, I (Priština, 1956), pp. 319-27 (Croatian).

201

![]()

The other basilica appears to have been built on a very similar plan to that shown in Fig. 126. In its single nave part of a mosaic floor was found showing geometrical motifs in white, black, yellow, red and blue, and part of a votive inscription. A narthex was also uncovered, paved with re-used marble slabs, and having two rectangular side chambers, which may point to a mid-sixth century date.

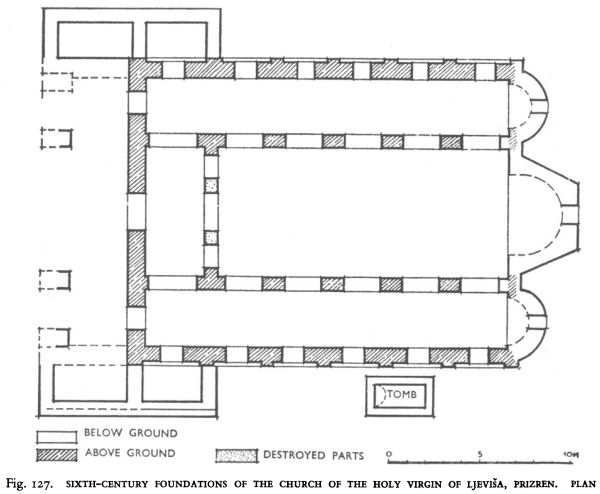

22. THE SIXTH-CENTURY FOUNDATIONS OF THE HOLY VIRGIN OF LJEVIŠA, PRIZREN

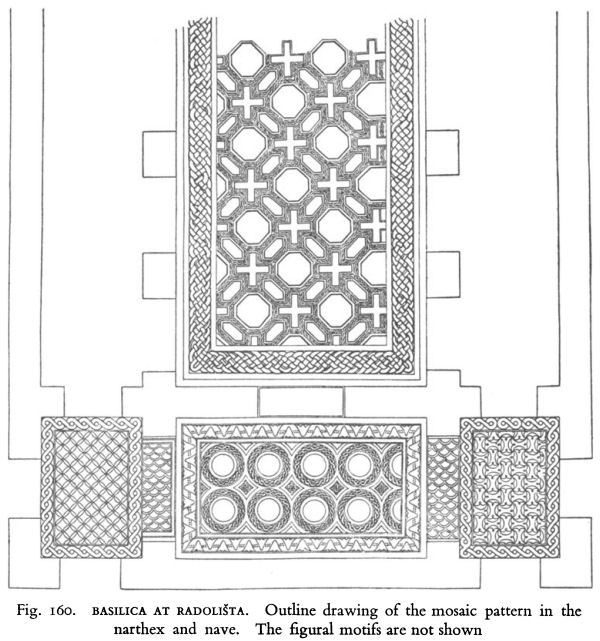

In the town of Prizren, the Hellenistic site of Theranda, lying due west of Scupi (Skopje), King Milutin’s fourteenth-century church of the Holy Virgin of Ljeviša is built on the foundations of a sixth-century basilica. Although no more than its general plan can be made out to-day, Nenadović has shown that it comprised a timber-roofed nave and two aisles of Hellenistic proportions, each terminating in a protruding eastern apse, the middle one of which was three-sided on its exterior. [1] At the western end, as in the region of Caričin Grad, rooms again projected north and south of the narthex. West of these, moreover, were two others, the western walls of which were joined by a portico or by a wall with a portico in the centre, echoing once again the ancient Hittite ‘Hilani’ narthex.

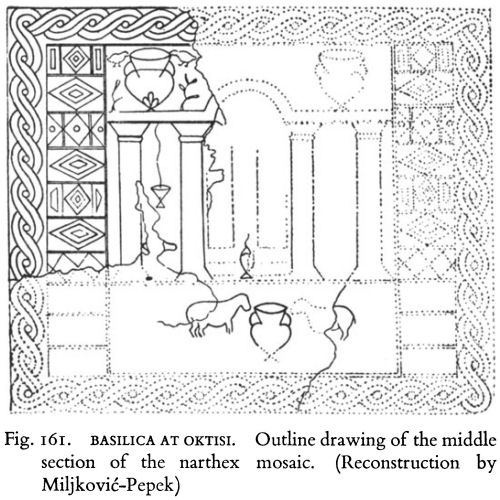

Fig. 127. SIXTH-CENTURY FOUNDATIONS OF THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY VIRGIN OF LJEVIŠA, PRIZREN. PLAN

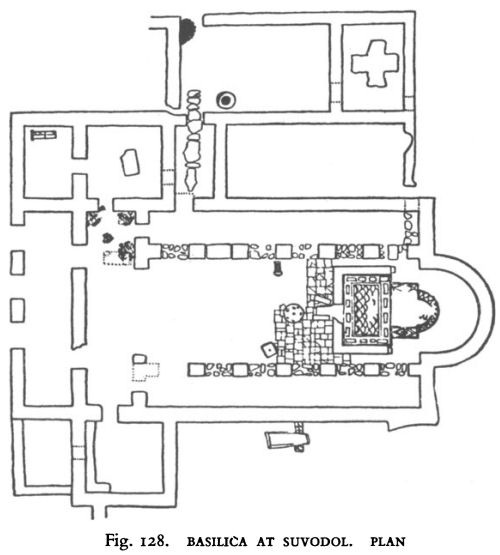

23. THE BASILICA AT SUVODOL (Pl. 56)

Not far from the site of Heraclea Lyncestis, Suvodol lies 19 kilometres east of Bitola.

1. S. M. Nenadović, ‘What were the Restorations of King Milutin in the Church of the Holy Virgin of Ljeviša at Prizren?', Starinar, 1954-55, pp. 205-26 (Serbian).

202

![]()

Here, in 1931, excavations, undertaken not in consequence of an aerial survey but on the inspiration of a local peasant’s dream, disinterred the ruins of an early Byzantine basilica. [1]

This basilica possessed several characteristic Hellenistic features such as a nave and two aisles with a single semicircular protruding apse, a narthex, a sanctuary consisting of a bema extending into the nave, but without parabemata, and galleries above the aisles.

The ground plan, however, reveals some divergences from the Hellenistic model. The nave, 15.60 metres long, is 6.20 metres wide, while the aisles are but 2 metres wide. The apse projects the length of the church 3.30 metres to the east, while the narthex and an exonarthex each add 3 metres to the west. The stone walls are uniformly 0.70 metres thick, except for the apse, which is 0.80 metres. Instead of columns, five massive brick piers, 0.90 by 0.70 metres, line each side of the nave. Finally, the narthex opens to the north and south into square, projecting chambers. The northern of these leads to another room to its west, lying flush with the exonarthex. A clumsily constructed room, apparently a later addition, was erected to the west of the southern extension of the narthex and to the south of the exonarthex. It is likely, but not certain, that a tribelon connected the narthex and the nave.

The nave was paved with stone slabs, but the bema, the level of which was raised by approximately 0.12 metres above that of the nave, possessed a mosaic floor arranged in three zones. The westernmost, lying inside the stylobates of the chancel screen, consisted of a fish-scale design in red, white and light violet tones. It was edged with a Meander border enclosing fruits and flowers. The middle zone, somewhat smaller and the site of the altar table, has been almost entirely destroyed: little more than a single diamond motif containing a quatrefoil remaining at the southern end. The pattern of the border on its northern and southern edges, a design formed by a series of semicircles, was repeated on a rather more spacious scale around the third zone. Of this, which was very slightly horseshoe in shape, only small fragments remain, the most important being the foot and part of the tail of a bird at the southern extremity.

Fig. 128. THE BASILICA AT SUVODOL. PLAN

Parts of the chancel screen have also survived. Its pillars were 1.90 metres high, the lower half being square in cross-section and faced with a plain linear design. The upper half was rounded and carried a simple form of Corinthian capital. A plain architrave, ornamented only by crosses at points where it rested upon the capitals, surmounted the whole. Three varieties of chancel slabs have been reconstructed. One, 0.88 by 0.75 metres, was decorated with a fishscale design in relief. In another, 0.875 by 1.35 metres, a diamond-shaped lozenge within a rectangle enclosed a stylised acanthus pattern. Symbols of Christian significance appear in the comers of the rectangle. While the decoration of both these slabs may reflect that of the mosaic floor of the bema, the third type strikes a different though no less traditional note. It bears an eight-armed cross — formed by eight ivy leaves — encircled within a double ring of ivy tendrils, the ends of which extend outwards to terminate in a leaf upon which stands a cross.

A doorway near the west end of the north aisle led into a passage and two rooms, in the more northerly

1. F. Mesesnel, Preliminary Report in Bulletin Scientifique de Skoplje (Skopje, 1932), p. 202 (Serbian); ‘Die Ausgrabungen einer altchristlichen Basilika in Suvodol’ (Acts of the IVth International Congress of Byzantine Studies), Bulletin de l’Institut Archéologique Bulgare, vol. x (Sofia, 1936), pp. 184-94.

203

![]()

of which the ground-plan shows a cross-like form. The excavators report this room to have been used as a kitchen and the cross-like shape to have been a hearth. Such a use certainly belongs to a later period. One wonders whether this part of the building might not originally have been a baptistery, with a cross-shaped baptismal pool that was later converted to a profane and mundane function.

Fig. 129. BASILICA AT SUVODOL. Fragments of pillars and the architrave from the chancel screen

Time and events were certainly ruthless with the structure of the church itself. It was probably burnt and reduced to ruins when the Slavs finally completed their conquest of the countryside about the end of the sixth century. Later, following the conversion of the Slavs, a smaller church was built from the nave and apse by walling-up the spaces between the piers. In time, this, too, was destroyed, perhaps under the Turkish regime. Finally, a tiny, primitive chapel, constructed among the ruins of the western part of the south aisle, served the humble needs of the reduced and poverty-stricken community.

It is interesting to compare the Suvodol basilica with that of Prizren. Their western ends are closely similar, particularly the Anatolian-type annexes of their narthices. Yet, in both cases, and especially in Suvodol, the Hellenistic influence remains strong, a contrast with Caričin Grad which geographical location and its cultural traditions may explain. The same reasons may account for the absence of the Syrian influences which are so prominent in the eastern districts of Macedonia.

Mesesnel dates this church to the first half of the sixth century ; Nikolajević-Stojković, on the evidence of the sculptured fragments, supports the middle of the sixth. [1] These datings certainly accord with the historical and social context.

24. THE SIXTH-CENTURY CITY OF CARIČIN GRAD

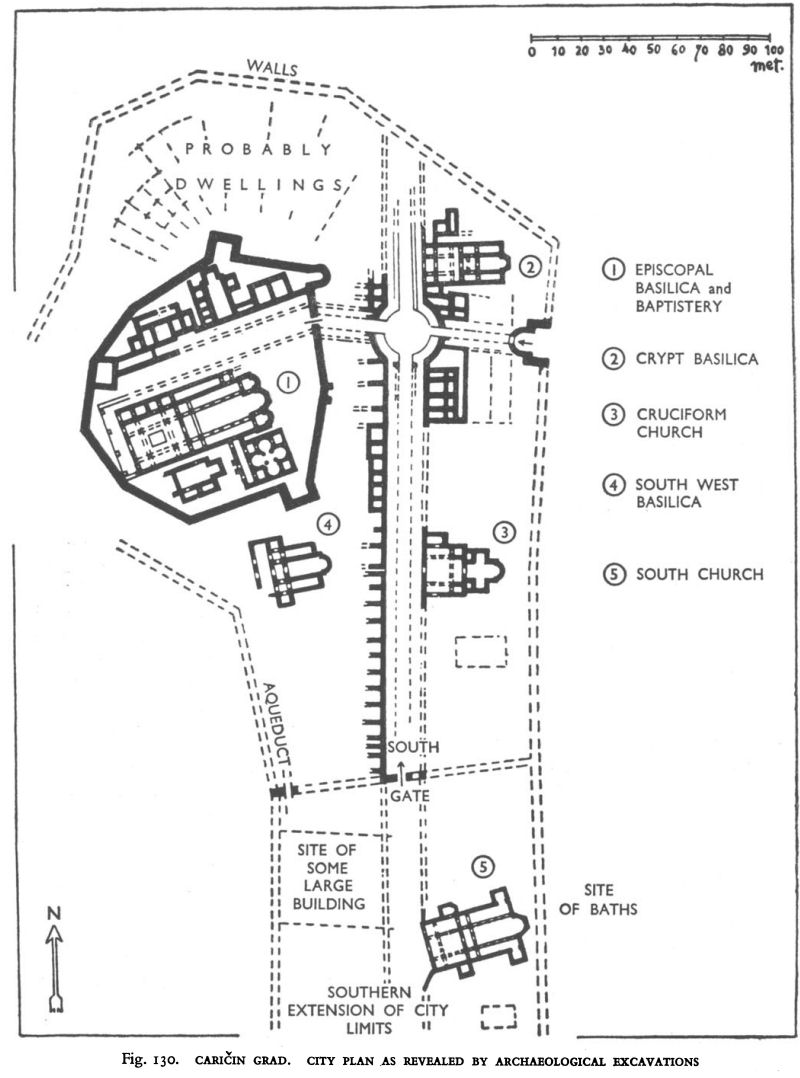

The sixth-century city of Caričin Grad (or Tsarichin Grad), to use the name by which it is known to-day, was built on a neck of rising ground at the fork of two small rivers, the Svinjaricka and the Caričinska, which enclose it on the east, north and west sides. The site lies six kilometres from modem Leban and an approximately equal distance from Niš and Priština. First excavated in 1912, in the intervals between wars, a very considerable amount of work has since been and is still being accomplished that has added a great deal to our knowledge of the central Balkans in the sixth and seventh centuries. The highest part, or acropolis, of the city, contained the episcopal quarter and was enclosed within powerful ramparts having an eastern gate flanked by two towers. A paved road, lined by porticoes, ran from this gate in a west-south-westerly direction to divide the episcopal quarter into two.

The buildings within the acropolis, for all its fortified character, all appear to have been constructed for ecclesiastical and not for defensive purposes. They were grouped around a large basilica, situated to the south of the paved road. A baptistery, constructed in the form of a quatrefoil inscribed within a square, was connected by a portico to the south aisle of the basilica, and to the east of this was a free standing hall or chapel with a projecting rectangular eastern chamber or apse. North of the road was the Episcopal Palace, containing a large and splendid ceremonial hall in three sections with several side chambers, some of which were capable of being used for meetings and other ecclesiastical functions. Other rooms served as living quarters and episcopal offices. Hypocausts provided heating for all this section.

1. I. Nikolajević-Stojković, Early Byzantine Decorative Architectural Sculpture in Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro, pp. 43-4, 90 (Belgrade, 1957) (Serbian with full French summary).

204

![]()

Fig. 130. CARIČIN GRAD. CITY PLAN AS REVEALED BY ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS

205

![]()

To the west were rooms which may have served as lodgings for visiting clergy or, perhaps, for civil functionaries from the capital. To the east were service quarters and workshops.

From the gate of the acropolis a road lined with porticoes ran east, intersecting a north-south road at a ‘round point’ or circus, and terminating at a Ushaped indentation in the eastern wall of the city. Contrary to earlier held opinion this seems to have served as an ordinary city gate, although excavation has indicated a solid construction pierced only by a drain or canal leading from the episcopal quarter to the river Caričinska. At this point was some kind of barrage or weir, probably for the purpose of working watermills, and it is likely that a bridge connected Caričin Grad with the outlying fort of Sveti Ilija.

The city’s main axis was the north-south road and, although the city walls bulged to the west to include the episcopal quarter, even so the maximum breadth of the walled city was but two hundred and fifty metres compared with an original length of about three hundred and twenty metres from north to south. Sometime subsequent to the foundation of the city, the north and south walls were extended in a southerly direction to incorporate a further stretch of relatively high ground and give the city a total length of some five hundred metres. The second or outer of the two southern gates and the two corner bastions of the southern outer wall have been excavated. A round tower stood at the south-eastern corner, while at the south-west a rectangular strongpoint protected the entry of the aqueduct which brought drinking water into the city and filled the moat protecting the southern wall.

With its straight, well-laid-out streets, its circus at their point of intersection, all fronted with porticoes, Caričin Grad was typical of early Byzantine townplanning. Unlike most of its contemporaries, however, it appears to have been neither encumbered with earlier buildings nor built over in later ages, facts which give it a unique archaeological importance. Although much still remains to be accomplished, a number of sixth-century dwelling-houses and shops have been excavated, principally those lining the main streets and, in the north-east and south-east quarters of the inner city, the sites of two more churches have been discovered. The first, a basilica, is peculiar in that it has a large crypt beneath the nave and aisles ; the second is built on a cruciform plan with western side-chambers. Another, of a rather more humble nature, was found immediately south of the acropolis.

In the southern part of the town, within the later extension of the walls, a fifth church has been excavated. This is a basilica with an eastern T-transept and two annexed chambers at the north-east and the south-east comers of the atrium.

The city of Caričin Grad was short-lived. It was probably evacuated by Byzantine forces during the first half of the seventh century, a mere hundred years or so after its foundation. An account of its final stages, as revealed by excavations, has already been given at the end of Chapter VIII.

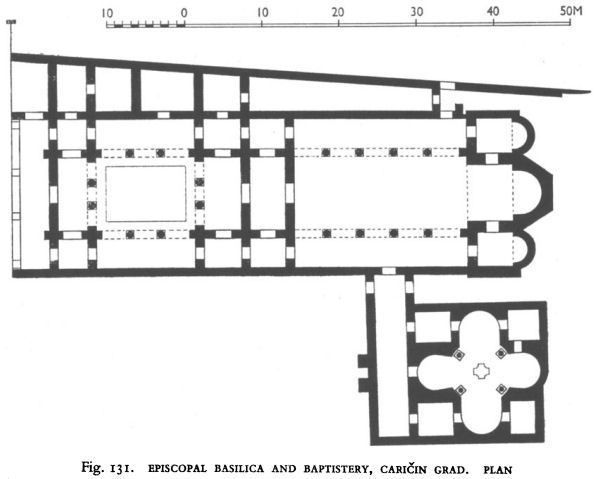

25. THE EPISCOPAL BASILICA, CARIČIN GRAD (Pls. 57, 58)

The Episcopal Church was a triple-naved basilica with a narthex, atrium and subsidiary rooms which ran along its northern side and fronted on to the road. It was a large church, 22 metres wide and 64 long with the atrium, 37 metres excluding it. The walls were brick ; stone only being used for later repairs. Four columns each side of the central nave separated it from the two lateral aisles. Petković, during the excavations of 1936, deduced from four massive slabs lying in the nave that the basilica carried a central dome, [1] but more recent opinion attributes a timber roof. [2]

The eastern end of the church was constructed in tripartite fashion, with the bema opening freely into the nave while the parabemata or pastophoria were structurally divided from the aisles by walls through which access could be obtained by doorways. Stepped presbytery seats ran along the north and south walls of the bema. Eastern apses terminated each of the three chambers of the tripartite sanctuary ; the two outer being semicircular inside and out, the central one, which was larger, having a rounded interior and a three-sided exterior.

1. V. Petković, ‘The Excavations of Caričin Grad near Leban’, Starinar, 1937, pp. 81-92 (Serbian).

2. A. Deroko, Monumental and Decorative Architecture in Mediaeval Serbia (Belgrade, 1952), p. 49 (Serbian).

206

![]()

Fig. 131. EPISCOPAL BASILICA AND BAPTISTERY, CARIČIN GRAD. PLAN

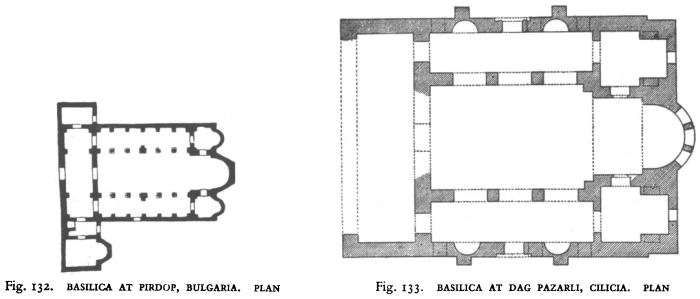

These sanctuary arrangements compare with those ofCurline (Fig. 104), Prokuplje (Fig. 105) and Pirdop (Fig. 132) and further investigation and excavation may include others, among them Prizren, in the same category. Outside the central Balkan provinces we find an earlier, very similar arrangement of the sanctuary in the church at Dag Pazarli in Cilicia (Fig. 133) which is thought to have been built in the late fourth or early fifth century and reconstructed following a fire probably sometime during the fifth.

Fig. 132. BASILICA AT PIRDOP, BULGARIA. PLAN

Fig. 133. BASILICA AT DAG PAZARLI, CILICIA. PLAN

Three entrances leading from the atrium into the narthex corresponded with three from the narthex into the nave and aisles. There was no tribelon.

Although the atrium was lined with the usual colonnaded portico, a sunken pool, 12 metres in length and provided with walled sides, replaced the customary central courtyard. Water entered the pool through holes in the sides and the overflow was carried away by a pipe or drain situated at the western side just below

207

![]()

the level of the floor of the church. No water source has been discovered by the excavators, who suggest, however, that there may have existed a medicinal spring, the curative properties of which perhaps provided a motive for the church’s original foundation. [1]

Small sections of mosaic flooring have been uncovered in the nave. These reveal a series of squares, each containing either a bird, which may be accompanied by an olive branch, a cup, or an embroidered sack filled with fruit. Each square is enclosed within thick borders of a guilloche or rope pattern. However, too little flooring remains, and the sections are too incomplete and damaged, for the full design to be reconstructed. Nevertheless, its relationship to the floor of Room 5 in the Summer Palace at Stobi is evident. It is of particular ethnographical interest to note, too, that the embroidered sacks of fruit, which, with the birds, are features of the Caričin Grad and Stobi pavements — and of Macedonian peasant life to-day — appear in the narthex pavement of the church at Dag Pazarli in Cilicia. [2] Individual glass and stone tesserae of many different colours found during the excavations indicate that the walls also carried mosaics, but no clue remains to their subjects or treatment. If Caričin Grad was indeed Justiniana Prima, the favoured foundation of the emperor, then, perhaps, we must turn to the apse of S. Vitale in Ravenna to gain some idea of the one-time splendour of its Episcopal Church.

A few Corinthian-type capitals have survived which probably surmounted the columns of the nave. They are clearly contemporary with the church. The acanthus leaves have lost the grace of earlier periods, and animal protomes tend to replace volutes at the comers of the upper band. The capitals from the atrium, however, are of the Ionic-impost type. Nikolajević-Stojković, discussing these capitals, together with those of the South Church and the Crypt Church, writes:

Their appearance illustrates a step in the transformation of Ionic-impost capitals into impost capitals. But whilst one would expect in such a case that the Ionic part would be reduced in favour of the impost, here the exact opposite happens : the Ionic part of the capital, although only decorative, is the chief characteristic of these monuments. On the front faces only very twisted spirals remain instead of plastic volutes, and the ‘echini’ have vanished without trace. Yet, the lateral faces have retained the plastic ‘pulvini’, which are sometimes smooth and sometimes decorated with tapering leaves, always joined in the middle. While the capitals of the Episcopal Church and the Crypt Church (also the triple-apsed church at Kuršumlija, and the churches in the village of Rudar near Leskovać and in Curline) have imposts decorated in the same way with crosses on the front faces, the only ornament on the back is the spiral. [3]

In this simple spiral decoration we have another distinct, if minor and unimportant in itself, link with Asia Minor, for Gertrude Bell illustrates the same motif on one of the double columns of Church No. 5 at Bin Bir Kilisse. [4]

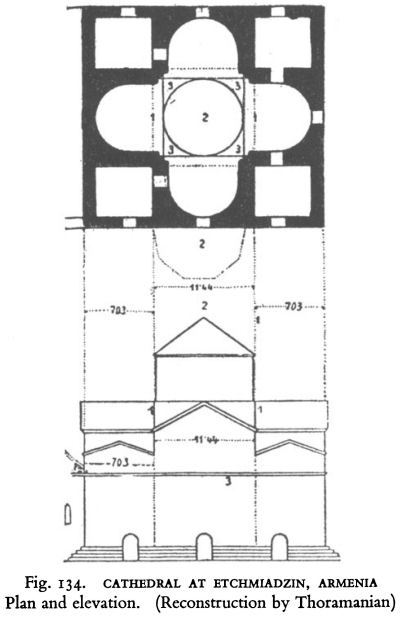

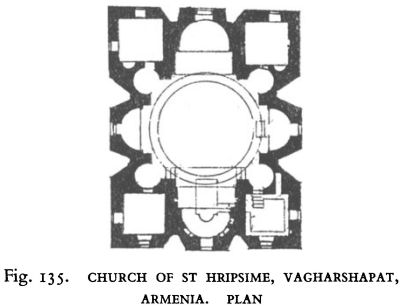

A porticoed passage leading from a door in the middle of the wall of the south aisle of the Episcopal Church ran along the western face of the Baptistery, basically a quatrefoil inscribed within a square, which included four rectangular rooms in the corner spaces between the arms of the quatrefoil. The latter were rounded in the form of apses, the eastern and western being slightly horseshoe-shaped. The angles at the meeting points of the arms were hollowed out like segments of a circle and, in the four spaces thus left, pillars, with Corinthian-type capitals similar to those from the nave of the basilica, supported a central dome. Beneath the centre of the dome was a cruciform trench, 1.85 by 2.00 metres and 0.45 metres deep, lined with bricks and with a marble revetment, which must have been the baptismal pool. The similarity in plan between this baptistery, the cathedral of Etchmiadzin (483-4) (Fig 134) and St Hripsime at Vagharshapat (618) (Fig. 135) may indicate an Armenian influence.

Fragments of polished marbles and mosaic tesserae show that the central space and the four arms were richly decorated, probably with multicoloured marble skirting on the lower parts of the walls and mosaics on the upper parts, the central dome and the vaulted arms.

1. V. Petkovič, op. cit. pp. 81-92.

2. Illustrated London News (18 Oct. 1958), pp. 644-6.

3. L Nikolajević-Stojković, Early Byzantine Decorative Architectural Sculpture in Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro, pp. 50, 92 (Belgrade, 1957) (Serbian with French summary) (trans.).

4. W. Ramsay and G. L. Bell, The Thousand and One Churches (London, 1909), fig. 29.

208

![]()

Mesesnel reports that only indistinct traces of mosaic flooring were found in the four corner rooms, but that all the arms of the cross were paved with mosaics displaying many different colours. In the north and south arms the designs were purely geometric ; in the east and west arms they included animal and vegetable motifs as well. Mesesnel describes the decoration of the eastern arm as especially remarkable, depicting ‘particularly lively representations of a hare, a foal, an ibex, a butterfly and so on’ [1] (Pl. 57).

Fig. 134. CATHEDRAL AT ETCHMIADZIN, ARMENIA Plan and elevation. (Reconstruction by Thoramanian)

Fig. 135. CHURCH OF ST HRIPSIME, VAGHARSHAPAT, ARMENIA. PLAN

Although at least a century later than the baptistery of the basilica at Tebessa in Algeria, this quatrefoil or cruciform may have been developed independently. With either the tripartite sanctuary or the trefoil memorial chapel it proposed the sacred number seven (see page 36). If it is possible to draw any conclusions from so few examples as the two baptisteries at Caričin Grad and Stobi, it would appear that towards the middle of the sixth century in this central Balkan region the quatrefoil appears to have been preferred as a baptistery and the trefoil as a memorial chapel.

It is likely that the Episcopal Church and its accompanying buildings would have been among the earliest to have been erected in a new city such as Caričin Grad. This would place them within the period 527-36, which Mano-Zisi designates as the first phase of the building of Caričin Grad, [2] an attribution which is supported by the style of the sculptured decoration.

26. THE CRYPT BASILICA, CARIČIN GRAD (Pl. 58)

In the north-east quarter of the city stood the Crypt Church, a basilica with an atrium, 35 metres long in all, which opened on to the north street. The main part of the church has not survived, but Spremo-Petrović, who excavated the site, has been able to reconstruct it as a basilica with a nave and two aisles separated by twin rows of four columns, and a single protruding apse with a rounded interior and a three-sided exterior. There was no narthex and three doorways led directly from the atrium into the nave and aisles. [3]

Beneath this superstructure was a large crypt, divided into three on the lines of the upper nave and aisles and possessing a similar form of single projecting apse.

1. F. Mesesnel, ‘The Excavations of Caričin Grad of 1937’, Starinar, 1938, pp. 179-98 (Serbian).

2. G. Mano-Zisi, ‘The Excavations of Caričin Grad in 1953 and 1954’, Starinar, 1954-55, pp. 155-80 (Serbian).

3. N. Spremo-Petrović, ‘The Crypt Basilica of Caričin Grad’ Starinar, 1952-53, pp. 169-80 (Serbian).

209

![]()

Fig. 136. CRYPT BASILICA, CARIČIN GRAD. Plan of the atrium and crypt with section showing levels excavated

Fig. 137. CRYPT BASILICA, CARIČIN GRAD. Plan of the atrium and nave. (Reconstruction by Spremo-Petrović)

Fig. 138. CRYPT BASILICA, CARIČIN GRAD. Longitudinal and latitudinal sections. (Reconstruction by Spremo-Petrović)

210

![]()

Unlike the superstructure, however, the crypt possessed a form of narthex, also divided into three sections, which corresponded to the western parts of the nave and aisles. As the church was built on ground which sloped steeply downwards from west to east, the narthex, nave and apse of the crypt were each stepped one lower than the other. The floor of the aisles, nevertheless, remained on the same level as the narthex.

The nave of the crypt measured 8.05 metres long and 5.67 metres wide. The aisles were much narrower, being only 2 metres wide. Massive outer and partition walls, 1.40 metres thick, of brick upon stone foundations, supported brick vaults, 0.60 metres thick, over the nave and aisles. No remains of vaulting over the narthex have been found and, since its walls were here only 0.90 metres thick, it is unlikely that this form of roofing was used. There was a doorway at the east end of the southern aisle, where the slope of the ground completely exposed the apse of the crypt.

The atrium consisted of a rectangular courtyard bordered with porticoes. The capitals of the columns were of the same type as those of the atrium of the Episcopal Church. A channel provided for the entry of a supply of water through the north wall into the central space.

The entire destruction of the upper part of the church and of all the mural decorations of the crypt leaves us with no direct clue to the specific purpose for which the church was founded. A church crypt was traditionally the site of the tomb or relics of a martyr, but it had also become the place of burial for leading church dignitaries. That the crypt should extend, in basilical form, beneath the whole extent of the nave and aisles, however, is unusual. In the basilicas of St Peter of Rome, St Demetrius of Thessalonica, and the Basilica of Bishop Philip at Stobi, the martyrium crypt was only beneath the sanctuary. The Early Christian cemetery crypts at Naissus (Niš) consisted of single chambers, as did those below the floor of the Constantinian basilica at Philippi. The latter were, moreover, constructed after the church had been built.

At Caričin Grad the crypt formed the foundations for the superstructure of nave and aisles and it is this characteristic which differentiates the church from others of the city and neighbourhood. For a martyrium erected in honour of a particular saint it is abnormally large, and surely the place for such a memorial would have been the Episcopal Church, in which neither a crypt nor a martyr’s tomb have been discovered. On the other hand, it is too small to serve as a public cemetery church. Moreover, such churches were generally built outside the city walls, where ample space was available for the burial of the faithful.

Perhaps the answer is that it belonged to the same category as the Marusinac Cemetery Church outside Salona. Dyggve describes this as having ‘an exceptional position as it has never been open to the ordinary members of the congregation, but only particularly privileged persons had access to it. All seems to indicate that the cemetery and its buildings are based on some foundation that has been able to retain the sole right to the martyrs buried here for a small circle of high clerical and temporal dignitaries.’ [1] The Crypt Church of Caričin Grad lay outside the walls of the episcopal quarter, but in a privileged position within the city limits. Possibly it was built to be the private cemetery church of the bishops and, perhaps, of other leading dignitaries of Caričin Grad.

On these grounds, and on the evidence of the capitals from the atrium, we may regard the Crypt Church as belonging to Caričin Grad’s first phase; probably about the third decade of the fifth century.

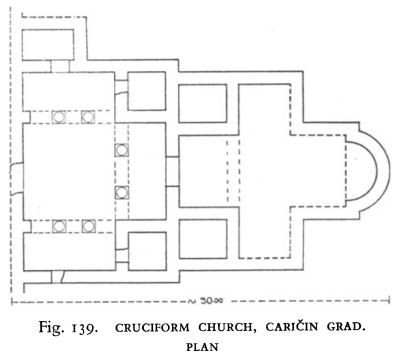

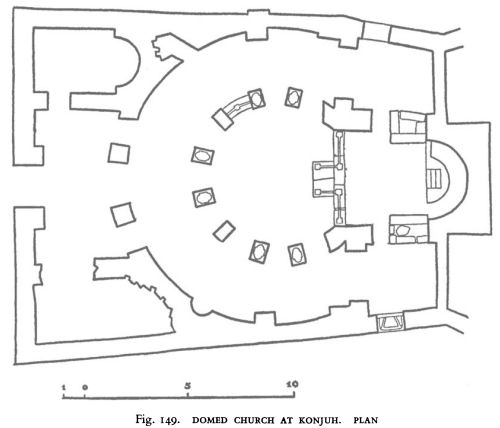

27. THE CRUCIFORM CHURCH, CARIČIN GRAD

In the south-west quarter of the city are the ruins of a Cruciform Church, the atrium of which fronts on to the main north-south street. This church takes the form of a Greek cross, with the western arm inscribed by two rooms. [2] Although the information so far available is somewhat meagre, the two inscribing rooms appear to correspond in some degree to the lateral sections of a narthex. To the west of this ‘narthex’ the foundations of a portico, flanked by two square rooms, each of which project the thickness of their outer wall north and south of the sides of the church, have been excavated.

1. E. Dyggve, History of Salonitan Christianity (Oslo, 1951), p. 76.

2. V. Petković, ‘The Excavations of Caričin Grad in 1938’, Starinar, 1939, pp. 141-52 (Serbian).

211

![]()

Fig. 139. CRUCIFORM CHURCH, CARIČIN GRAD. PLAN

These rooms also form the eastern comers of the atrium, in which a wall and a street entrance occupy the place of the normal western portico. The total length of the structure is 30 metres ; the church itself is approximately 17 metres from east to west and 16 from north to south.

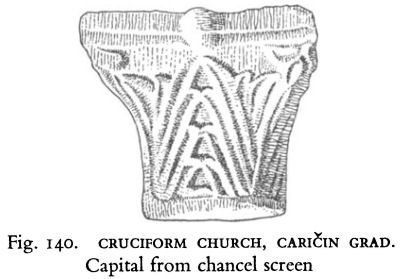

Two different types of capitals are illustrated by Petković. One, obviously belonging to the massive pillars of the atrium, is a solid, extremely simple, Ionic-impost capital. Its only decoration appears to be a medallion containing a cross. The second type, of which two have been found, is smaller; its form is Corinthian and its decoration consists of simply carved and highly formalised acanthus leaves. These two Corinthian capitals probably belonged to the chancel screen and indicate that this was of the high type carrying an architrave similar to that discovered at Suvodol.

Fig. 140. CRUCIFORM CHURCH, CARiČiN GRAD. Capital from chancel screen

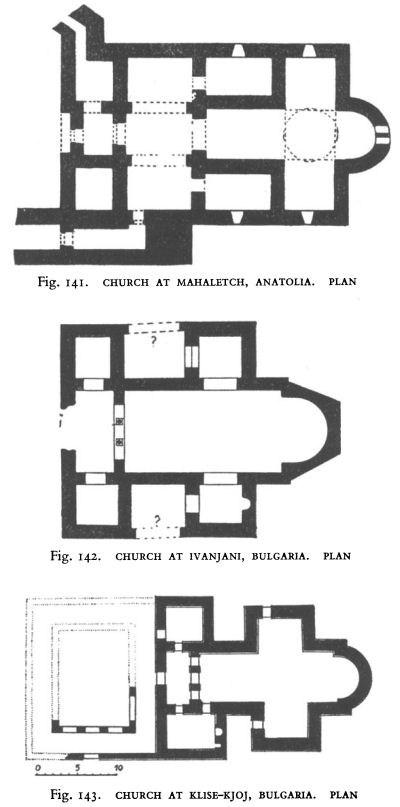

Fig. 141. CHURCH AT MAHALETCH, ANATOLIA. PLAN

Fig. I42. CHURCH AT IVANJANI, BULGARIA. PLAN

Fig. 143. CHURCH AT KLISE-KJOJ, BULGARIA. PLAN

In the architectural arrangement of its parts the Cruciform Church has certain points of resemblance with the crypt of the Crypt Church. The two ‘narthices’ correspond, as do the aisles of the Crypt Church with the north and south arms of the Cruciform Church. Moreover, just as the Crypt Church is likely to have been built with a funerary purpose in

212

![]()

mind, the cruciform plan was a particularly favoured form of a memorial church in eastern Anatolia. In this connection, too, the north and south arms of the Cruciform Church may be analogous to the side apses of the trefoil churches of Kuršumlija, Klisura and outside Caričin Grad, with the difference that one owes its inspiration to Anatolia and the other to Syria.

In view of the uncertainty concerning the exact liturgical purpose of the inscribing western rooms of the Cruciform Church, it is difficult to assess their importance. They have also been found to occur in Anatolia, as, for instance, at Mahaletch. [1] Without them, the church would clearly belong to the same type as those at Ivanjani and Klise-Kjoj in Bulgaria. Both these churches may be approximate contemporaries of the Cruciform Church and follow a plan which was to be adopted in the twelfth century by the Raška school of Serbia. The capitals indicate a date that is different from and probably a little later than either the Episcopal Church or the South Church. Perhaps we may assume that the Cruciform Church was erected sometime in the second half of the sixth century, possibly as a private chapel and memorial church of a military governor of Anatolian origin.

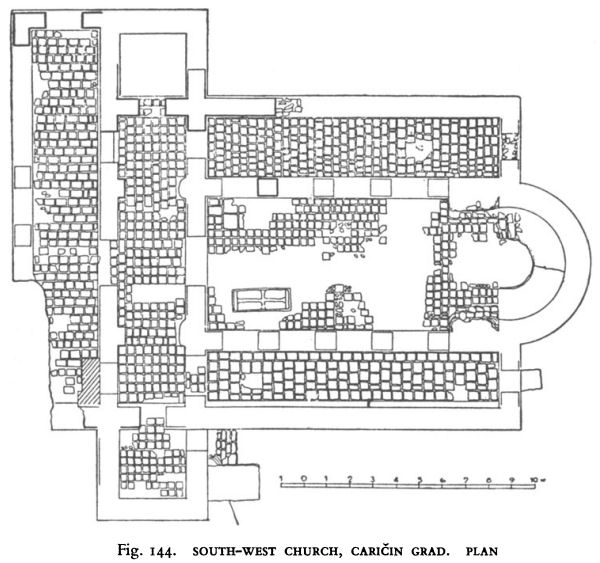

28. THE SOUTH-WEST BASILICA, CARIČIN GRAD

The last church to be excavated in Caričin Grad was not discovered until 1957. [2] It stood in the western part of the city immediately to the south of the episcopal quarter. Here the ground begins to slope steeply towards the south-west and it had been necessary to level the site before building could be started.

The church was a basilica with a nave and two aisles, all probably vaulted. Its single protruding apse was semicircular outside as well as inside, a Hellenistic feature which, in Caričin Grad, was shared only, and then to a modified degree, with the Cruciform Church. Low stylobates, each with four piers carrying arcades, divided the nave from the aisles. The stylobates and piers, like the walls and the floor, were constructed throughout of brick. A narthex, with openings into the nave and aisles, had three corresponding entrances from a western portico. Two more in its north and south walls led into square chambers which jutted beyond the sides of the basilica. Other doorways were sited at the eastern ends of the aisles, in the north aisle wall and in the east wall of the southern annexe. Because of the sloping ground the portico did not extend southwards beyond the narthex.

In contrast to the western end of the basilica which conformed to a pattern common to other churches in the region, the internal as well as the external arrangement of the apse was quite different from any other yet excavated in the neighbourhood of Caričin Grad. A stone bench, 0.50 metres high, which lined the apse wall, was covered subsequently to the building of the church by a subsellium reaching to a height of 0.85 metres. This structure was joined to stepped presbytery seats ranged opposite to each other on either side of the altar. We have already met such an arrangement at Voskohoria (Fig. 94) and probably at Ulpiana (Fig. 126). Mano-Zisi, who excavated this church, instances further parallels in Basilicas A and B at Nea Anchialos near Thebes, in Basilicas A and B at Nicopolis and probably in the Basilica of Bishop Philip at Stobi. The Greek origin of this form of sanctuary seems, therefore, to be in little doubt.

In its size, in all only 25 metres long, and in its execution, the South-West Basilica strikes a keynote of modesty and simplicity. Clearly it served inhabitants of Caričin Grad who belonged neither to the wealthy nor to the influential classes. It probably served the spiritual needs of tradesmen and artisans grouped in the immediate locality ; some shops and workplaces have been identified. Was this element then largely Greek ? Although four graves were uncovered, two in the nave (one a stone sarcophagus with a Latin cross on the covering slab) and two in the narthex, there were no accompanying inscriptions which might have provided a clue. The only other evidence of an ethnic nature found on the site belongs to the later Slav occupation.

1. W. Ramsay and G. L. Bell, The Thousand and One Churches (London, 1909), pp. 241-56.

2. G. Mano-Zisi, ‘The New Basilica of Caričin Grad’, Starinar, 1958-59, pp. 295-305 (Serbian).

213

![]()

Fig. 144. SOUTH-WEST CHURCH, CARIČIN GRAD. PLAN

Mano-Zisi dates this church to the period of Justinian (527-65) and it is difficult to be more precise than this.

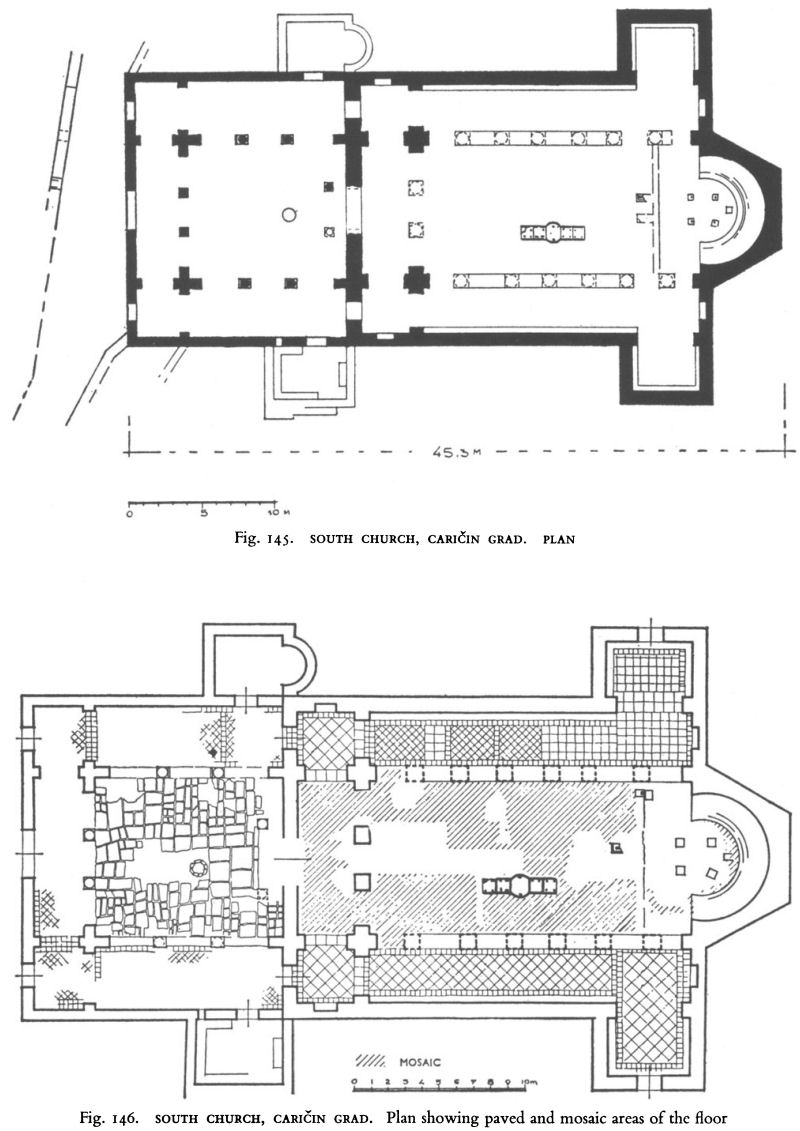

29. THE SOUTH CHURCH, CARIČIN GRAD (Pls. 59-61)

The South Church lies within the southern extension of the city walls of Caričin Grad. It is a Ttransept basilica and has a single protruding apse that is three-sided on the outside and horseshoe-shaped inside, a nave and two aisles, a narthex, and an atrium. From the north and south sides of the last jut two chambers, the northern possessing an eastern apse, corresponding to the wings of the nave transept. It is likely to have had galleries above the narthex and aisles and, in all probability, a timber roof, with, perhaps, clerestory lighting. The whole length is 45 metres and the width of the nave and aisles together is 20 metres. [1]

The walls consist of alternate layers of brick and stone built upon foundations of carefully fitted stone blocks. Brick arcades rested upon the columns, which, spaced unevenly, divided the nave from the aisles. These columns ran uninterruptedly from the two pilastered or cruciform piers flanking the tribelon to the eastern wall of the church, the last ones on each side standing within the area of the transept and sanctuary. Presbytery seats were placed around the apse and four bases of dborium pillars situated immediately in front of them indicate the position of the altar. Arched openings connected the wings of the transept with the main body of the church. There are signs of marble slabs having been used as skirting in both transept wings and in the apse.

Crumbling remnants of painted plaster show that the walls of the aisles and of the transept wings were originally decorated with wall paintings. The presence of large numbers of tesserae in the nave and the porticoes of the atrium indicate, however, that wall mosaics were used in the more important parts of the church.

1. G. Mano-Zisi, ‘The Excavations of Caričin Grad, 1949-52’, Starinar, 1952-53, pp. 127-54 (Serbian).

214

![]()

Fig. 145. SOUTH CHURCH, CARIČIN GRAD. PLAN

Fig. 146. SOUTH CHURCH, CARIČIN GRAD. Plan showing paved and mosaic areas of the floor

215

![]()

Fortunately much of the original floor, including large areas of mosaic, has survived almost intact, and, apart from the great intrinsic interest of the designs, this has been a considerable help in elucidating the liturgical planning of the church. The flooring material of the aisles, the transept wings, and the lateral compartments of the narthex was brick, for the most part laid in a simple diagonal pattern within a border that ran parallel to the walls.

The central area of the church — the narthex, the nave and the bema — possessed a mosaic floor, the patterns of which took account of the importance and function of each part. The tesserae display a considerable variety. Materials used included stone of various kinds and colours, brick, ceramic, glass and enamel. The colours included reds, blues, greens, yellows, ochre, browns and black, as well as white, which was generally used to form the ground for the design. The objects and figures portrayed were executed in finer and smaller tesserae than the rest and particular care was given to the modelling of human faces and animal heads. In such cases both shading and contrast line techniques were employed.

The narthex floor (Pl. 59) was originally a single composition, but the southern end evidently required replacing at some later date. As the design is upright when looked at from south to north, it would seem that either the usual entrance to the church from the atrium was through the southern door of the narthex, or those taking part in the Eucharistic service entered the nave from the south aisle by passing through the southern chamber of the narthex. Basically, the design consists of an interlacing motif providing alternate rows of circles and concave octagons. Within the circles birds of different kinds are portrayed freely and realistically. In the octagons are various kinds of vessels, especially chalices and goblets, and dishes and baskets or sacks of fruit. The incomplete octagons around the edges of the pattern contain leafy branches. The later mosaic at the south end of the narthex is less finely executed. A diagonal pattern divides it into four triangles, in each of which two birds peck at grapes on vine branches issuing from a large amphora.

The whole area of the floor of the nave from the tribelon as far as the entrance into the sanctuary through the chancel screen has been treated as a single composition, the liturgical message of which is presented to the worshipper as his eyes travel towards the altar. The whole composition, only interrupted by the ambo, is enclosed within a uniform double border, the outer composed of two winding bands forming a series of circles enclosing designs of crosses, the inner a spiralling ‘wave’ pattern similar to the ones found in the floors of many other early Byzantine buildings, including the ‘Extra Muros’ basilica at Philippi and Caričin Grad’s Episcopal Church. It may be noted that in both the Caričin Grad examples the spiralling is characterised by the same degree of emphasis that appears in the Ionic-impost capitals.