The Administration Building of the Bulgarian State University

CHAPTER X

Getting wise

B.

Another helpful activity carried on by the Ministry of Education is the sending of moving pictures to the villages. Each outfit consists of a truck with a movie machine, films and light producing apparatus, of a chauffeur-operator and of a teacher-conductor who is supposed to have a general encyclopedic knowledge, the gift of story telling, the power of roughing it indefinitely and a love for common people. Arriving in the obscurer villages, far off the beaten tracks, many of whose inhabitants have never been to a large city or ridden "on the cars", the movie men string up their canvas in the school yard or if the weather is bad in the largest room in the place while the town crier goes about with his drum calling his fellow peasants to see the show. The program usually lasts somewhat over an hour and consists of an innocent comedy film sandwiched in among many rolls of historical, geographical, scientific and moral pictures. On the whole, the program is very serious, as are the Minister of Education and the Bulgarians themselves. Many of the pictures pertain to agriculture, so the peasants, standing in their sheepskin coats and pigskin moccasins, are enabled to watch their fellows in Denmark, Holland, America and other advanced countries at work and in their homes. After the show is over the conductor is invited to spend the night as a guest in the best house in town; children crowd about to stare at the wonderful entertainer; old women press up to him and shaking his hand, bless the mother that bore him and for weeks the youth who gather at the fountains and the men who assemble in, the village coffeehouses talk of the things they saw on the screen and express their amazement at the new world they have discovered.

* * *

A more fruitful activity than this is the opening and maintenance of communal reading rooms in the towns and villages. Within the last few years hundreds of these have been created. They are supported for the most part by the income from communal land set aside by a special law for reading rooms and libraries. Many of these are of course still crude and primitive undertakings. They have not many books and but a few periodicals while the number of prominent people who come to give lectures in them is limited. Yet it is a very hopeful beginning.

The Administration Building of the Bulgarian State University

Little by little the number of books is increasing, a good many entertainments are given and helpful lecture courses are arranged. These rooms serve as the clubs of the more energetic, progressive youth in each community, who among other activities carry on a vigorous temperance movement. Almost all the local organizations are members of the Union of Bulgarian Reading Rooms and receive help and encouragement from the state. They make possible a very helpful contact between the writers, scientists and professors of Sofia and the people in the towns and villages. It is in them also and under the auspices of their directors that many excellent agricultural lectures and demonstrations are given. In general they are one of the chief sources of cultural activity among the peasants and provincials. At present 2,400 of them exist.

* * *

An activity of another nature carried on by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education is the encouragement of art and literature. This is done in several ways. In the first place the Ministry often buys the best pictures shown by Bulgarian artists at the various exhibitions. Then again it gives prizes every year to the authors of the best literary productions. In addition, it often buys many copies of the books of various authors, sending them to the reading rooms and to various official libraries. Finally, it finds employment for most of the more promising or distinguished writers in need of funds, providing them with modest salaries. Some call such positions sinecures but the writers themselves protest against this characterization, saying that they actually work for the money they receive. Most of them, indeed, do some work but the fact is that very few people in Bulgaria are able to make a living out of their writing and that the state usually does what it can to prevent talented creators from falling into want, by giving them jobs of a not very strenuous nature. These sinecures seldom bring their incumbents more than thirty dollars a month each and often less.

A good deal of democracy prevails in the management of Bulgarian schools. Generally speaking they are democratic where American school are autocratic and are absolutistic where American schools are democratic. For example, relations between the Bulgarian teachers and pupils leave much to be desired. They make one think of barracks, of the relation between army officers and soldiers. There is little intimacy and scant coJnradeship. In class the teacher is usually formal, giving his explanations in a rather dry manner and "raising" one pupil after another to answer conventional questions. The teachers pump knowledge into obedient pupils and then squeeze them to see how much comes out. The pupils all wear regular, official uniforms and are subjected to an impressive set of rules which govern their conduct in and out of school. Every student activity is extremely carefully controlled. In a word, there is a good deal of bureaucracy in the Bulgarian schools. Everything to be taught is carefully prescribed and at the end of each hour the teacher must write in a big book just what he has taught. Inspectors come around periodically to check up. Everything is made to fit into a fixed system. Teachers tend to become mechanical parts of a great educational machine.

No it's not lopsided! I sent the camera man to a tiny

remote village to take this picture on the first beautiful spring day,

when the sun was shining, the birds singing and the flowers blooming. His

machine seems to have got infected with the joy and gaiety of the little

children dancing beside it so it caught the building on a slant making

it look tipsy. But this is a perfectly good school, well equipped and sober.

Both its ends are of exactly the same size and its eyes are not out

There are several reasons for this mechanization of education in Bulgaria. One is that immediately after the liberation of the country many of the teachers were not efficient nor well trained, so continual supervision was extremely necessary. It was a means of teacher training. There was absolutely no other way to insure that everybody would be on the job, that he would cover the necessary material and that the diplomas from all the schools would have the same value. Eternal vigilance was the price of even moderate efficiency. Of course, this inflexible central control tended to smother the initiative of the more competent teachers but it also stimulated a host of very ordinary teachers to a higher standard of world. In a village where the mass of the people are ignorant, there is little expert social control and that necessitates more official control from people higher up.

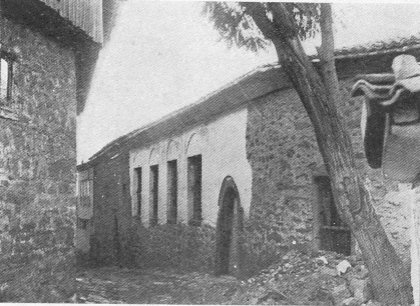

One of Bulgaria's first primary schools. It is in the

city of Tirnovo and had as its teachers a number of persons who later became

very distinguished statesmen and writers. A very large percent of Bulgaria's

leading men begin their career as shool teachers

In addition, it must be stated that relations between children and their elders have long been rather formal in Bulgaria, which was for centuries a patriarchal land. Children always used to obey their parents and especially their grandparents. They walked in thz beaten paths and "kept their places". Frivolity and caprice were frowned upon. Becoming behavior was the dominant ideal. Grown sons with children took orders from their fathers. Disregard of constituted authority was not permitted. Petting and pampering were considered harmful. Complete parental control was unequivocally accepted. So naturally this spirit was transferred to the school. On the whole that is what the parents want. At the same time it must be noted that in Bulgaria there

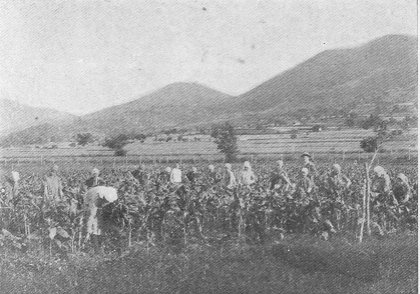

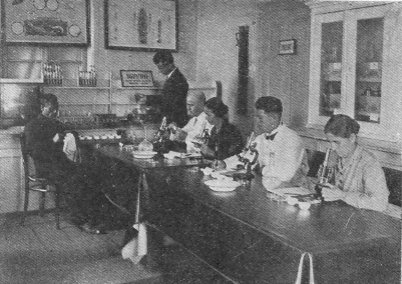

The pupils in a girls' agricultural school at work

has been and is an unusually violent struggle between the ideas of the younger generation and those of the older. A few decades ago Bulgaria suddenly passed from the patriarchal stage to modern democracy of a very advanced type. So naturally some of the youth wanted immediately to throw off the authority and ways of their fathers along with their long red belts and crude theology. God, the ten commandments, private property and the sanctity of laws were all in danger of going aglimmering. Communism and other golden-red panaceas swept like clouds of glory over Bulgarian skies and hundreds of young teachers became socialistic and communistic. These in turn imparted their ideas to the youth and a whole generation became imbued with insurgent ideals. This contributed toward the precipitation of a bloody civil strife and it is very natural that now the authorities are determined to exercise even stricter control than ever over the teachers and pupils.

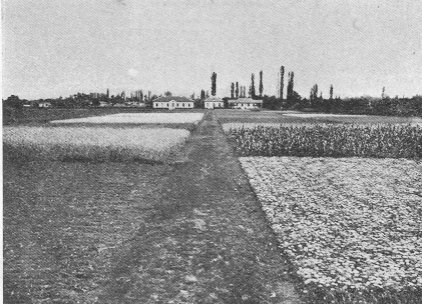

The boys' Agricultural School, at Sadovo

Yet in spite of this, the teachers in their relations with one nother and with most of their superiors are very democratic. They feel far more secure than their colleagues in America. Like Supreme Court judges they hold their jobs for life. Of course a teacher might be fired if he committed some heinous sin but dismissal would not be very easy nor could it be brought about summarily. A disciplinary court of his equals would have to deal with him and if they upheld him no minister, under ordinary circumstances, could dismiss him. Strange as it may seem the largest teachers' organization in Bulgaria is often in open conflict with the Ministry and prints ferocious attacks in its weekly paper against the Minister, yet most of the members of this association are not in danger of dismissal. Special laws, however, permit the Ministry to dismiss on its own authority teachers openly spreading communist ideas. On the whole this law is not abused.

A county school of carpentry and cabinet making

Ordinary teachers also in their relations with principals, directors and head teachers are in a position of almost complete equality. The teachers' body and not the principal manages a school. The principal has but little authority over his colleagues, in theory or fact. All school matters are considered and settled in the teachers' council. No principal has the power of hiring and firing. And his salary is but slightly greater than that of his colleagues. Each teacher also is the "guardian" of some class and as such has important responsibilities. In the University a new rector is elected each year. There the Academic Council has almost absolute power, on occasions openly defying the Minister of Public Instruction.

In the working out of the school program, also, the teachers have their part. The program once accepted is rigidly imposed on all the schools but it is a supreme council of the best pedagogues in Bulgaria that creates it. All the teachers and the citizens may express their opinion through their representatives so the courses of studies decided upon are a concensus of the best opinion in Bulgaria.

In the actual appointment of primary teachers and the maintenance of primary schools, local boards of trustees have much influence; in fact they appoint the teachers although they almost always work in close cooperation with higher educational authorities. Candidate teachers not approved by the requisite inspectors cannot be given positions.

The prevailing tone of the Bulgarian schools is austere. The pupils are supposed to spend most of their time studying. That is what they go to school for. They are not allowed to go to the movies, to the theaters or to dances except on very special occasions. They and their teachers wear modest clothes of a prescribed style and color. If boy and girl pupils are seen strolling together it usually means a case for the teachers' council. There is much written work, many tests and a very difficult examination of all the material covered at the end of the course. As a general thing Bulgarian pupils are required to work very hard on routine subjects and cover a large amount of rather dry material. They have many more class hours and much more studying to do at home than American youth. They have less spontaneity and initiative but acquire\ more knowledge about a wider range of subjects.

* * *

There is a four years elementary school course and then three years in a progymnasium, all obligatory for all children. Then come five years in a gymnasium, and after that the four years of the university. By the time one has finished the gymnasium, in which there are no elective courses, he has studied the Russian, German and French languages, world geography, ancient, medieval and modern history, organic and inorganic chemistry, physics and astronomy, botany and zoology, psychology and logic, the principal literatures of Europe, ancient and modern, a vast amount of mathematics including trigonometry and plane, solid and descriptive geometry, sewing, drawing, music, public speaking and dramatics with special emphasis on the Bulgarian language, literature and civil government.

An agricultural testing station at the service of the

peasants

The amount of material covered by Bulgarian high school or gymnasium pupils is enormous and the best of them acquire a most formidable general knowledge, but the system is weak in that it gives the youth too little opportunity for self-expression and for the satisfaction of their own creative inclinations. Generally speaking, Bulgarian young people from the best gymnasiums know considerably more of world history, geography, culture and thought than boys and girls of the same age in America, but they are less at home in the world, have less initiative and self-assurance and are less able to fit into the environment about them.

The Bulgarian educational system, of course, as every other, has many

defects. It errs on the side of rigidity and overcrowding, which is probably

better than being too slack and easy going. It gives more attention to

logarithms and Greek roots than to football or "proms" and makes order,

discipline and duty take precedence over spontaneity and caprice. It is

still striving toward a happy medium and has room for much improvement

but it is certainly one of the finest achievements attained by any people

in southeast Europe. In every town and larger village there is at least

one large, imposing modern building, the school. In every community there

is a little group of educated people who keep in touch with the outside

world and almost every year go to some large center for special courses

and conferences — the teachers. There is one kind of books that are distributed

by the millions, text books. Illiteracy has practically been wiped out

so that now fully 90% of the Bulgarian youth can read and write although

not more than seven decades ago more than 90% were illiterate. A Balkan

village is a drab and dreary place; many of the children there still sleep

on dirt floors, have no tables to study on and in long winter evening read

in the dusk created by smoking kerosene torches, yet a legion of devoted,

trained teachers are faithfully ministering to these most backward parts

of what was a century ago Europe's most backward country, bringing them

enlightenment and life. They are the apostles and heroes of the Balkans.

The Bulgarians have not the superb ancient culture in which the Greeks

rejoice, nor did they play the glorious role in the fight against Islam

of which their neighbors, the Serbs, boast; nor have they as exquisite

a sense of the delicately beautiful as that with which their gayer northern

neighbors, the Rumanians, are endowed; but they have surpassed every people

in the Near East in educational progress and continue to lead them all.

A faithful, patient school ma'am may take her place beside a magically

skillful gardener as one of 'the emblems of Bulgaria.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]