A scene of N. Petroff’s, the most gifted Bulgarian landscape painter

CHAPTER XII

Bulgarian art

Very recently a prominent Bulgarian assured me that water colors by the leading Bulgarian artists are second to none in Europe and when I showed some reluctance in accepting so sweeping a judgment, my interlocutor "guaranteed" me that his statement was perfectly accurate and offered to prove it by comparing the best Bulgarian paintings one by one with the best of the contemporary European masters. Being unacquainted with the European masters I accepted the guarantee on faith, though even yet I am a bit doubtful.

Nevertheless, I was very much impressed by the fact that a lawyer, who had given much of his life to politics and was at that moment engaged in trying to improve Bulgarian agriculture, should be so much interested in art.

This is not an isolated Bulgarian phenomenon. As the people love to sing, to participate in dramatics and to dance, so most of those who have gone through the grade school are interested in painting and drawing. And this is natural, for the study of art, forms an obligatory part of every school curriculum. Not long after one learns the three R's in Bulgaria he also learns to sing and draw. Every child at the end of the school year exhibits objects which he calls drawings or paintings or modeling and most of the pupils do not hesitate later to hang these creations on the walls of their homes and show them to kind neighbors. Thus, all being artists, the people are interested in art.

Then the fact that there are drawing teachers in all the schools in the country and an Art Academy to prepare such teachers, naturally keeps painting and drawing before the attention of a large public. It also enables hundreds of people to experience the charm and lure and mastery of color, form, shades and curves and inspires not a few persons to try to create something beautiful and striking and enduring.

Consequently there are many art exhibitions, a large number of art associations and not a few periodicals devoted to art; you often see men and women with their brushes or pencils engrossed in reproducing streams, crags and mountain ranges and not infrequently you find unfortunate artists at your door offering you their creations. Of course among a people of whom the greater part are peasants and most of whom a half century ago were illiterate the supply of art products exceeds the demand, while not a few of the creations are of very mediocre quality. Yet the fact that so many of the poor children of moccasined fathers and barefooted mothers undergo the greatest privations in order to learn to sing and paint reveals the strong artistic inclination of the Bulgarians, who in this respect resemble most Slavs. It is probably more important for a peasant youth to learn deep plowing and seed selection and to build a walk through his muddy yard than to draw a futuristic picture' that might be taken for a pile of wood or a Gothic cathedral but the impulse to create will establish an equilibrium, so that village improvement and oil paintings will both find their proper places eventually.

Bulgarian art is a comparatively new creation — almost as new as the state itself. To be sure, there were eikon paintings of a rather high order a hundred years ago. Likewise, a number of first rate artists appeared even before the liberation, at the same time that the awakening nation was beginning to print books and papers, to give theatrical performances and to insist on having mass sung in their own language. Yet practically all the art productions worth mentioning have been created since the nation won its freedom.

A scene of N. Petroff’s, the most gifted Bulgarian landscape

painter

Bulgarian art has passed through practically the same stages of development as Bulgarian literature, which is natural since they both spring from the same source and spirit. Many of the artists, in fact most of them, paint pictures like Vazoff's poems and stories; they rejoice in the liberation of their people, are delighted by a very beautiful fatherland, feel the power and charm of old customs, habits, costumes and dwellings, revel in the rich extravagance of fantastic legends, are inspired by the best folk songs, are moved by heroic acts in repeated wars and fall under the spell of the. austere, puritanic might of the frugal, rigid, small town artisans; so, as impressively, jubilantly or exquisitely as their talents permit, they put these feelings on canvas. The objects resulting from such domestic emotions have turned out to be the best Bulgarian art productions.

But such creations seem small, limited and provincial to certain painters and sculptors who have studied abroad and sensed the beauty, depth and challenge of a universal culture, so they, imitating some prevailing school or following some dominant movement, try to produce pictures and statues without the brand of the Balkans upon them. Such creations are often artificial and unreal and of inferior quality.

I shall not make any attempt here to prepare a catalog of Bulgarian painters and sculptors but shall merely walk with you through the large gallery of Bulgarian art and exclaim over the creations that I like to look at. If you find that annoying and a bit presumptuous, you may pass through the gallery later at greater leisure and stop before ,the pictures and statues that strike your fancy. But if it is your first trip let me give you the once over.

First, let us look at the sculpture. There is really quite a lot of it. And one of the cleverest, most amusing and most fascinating pieces is a little statue of "The three Village High Monkey Monks". It does not represent the best Bulgarian workmanship nor is its creator, Yanko P. Pavloff, among the very first sculptors. So far indeed he has not produced very much, yet the many statues which he has not molded in no way detract from the worth of this one he has given us.

Pavloff's happy village triumvirate

It is a caricature in bronze, representing a fat village priest, a rather coarse, hard boiled village mayor and a skinny village teacher. They are walking arm in arm on top of the world, while the world is at the spring and the spring is — not at morn. So early in the morning these three celebrities would not have developed such perfect spiritual harmony nor would they have arrived at so happy and triumphant a point of view. The statue is somewhat brutal, but not so cynical as clever; not a criticism but a jest. It is the three "big bugs" as the villagers saw them; the mayor, the priest, and the teacher as the housewife thought they looked when they walked down the street past her door.

If you read this piece of bronze you will not have to read so many books in order to get a glimpse into village life and you will also understand Aleko Constantinoff's "Bai Ganyou" better. It is a brilliant wordless satire.

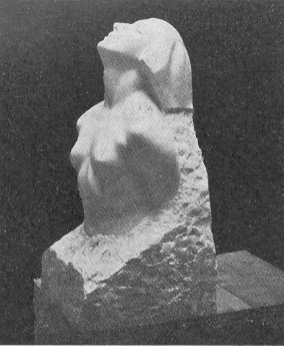

Which is, of course, rather rare since most Bulgarian sculpture is anything but humorous and mirth provoking. Some of it is exquisite and delicate with pure lines, grace, symmetry, elegance. It is light, white, dainty, alluring; like the innocent love on Keats's Grecian Urn, like all the classic sculpture through all the ages. Two of the foremost creators of this type of statues are Jeko Spiridonoff, a distinguished professor in the Art Academy, and Andrei Nicholoff, who has spent much of his time in Italy and is highly esteemed in European art centers. His work is the best the Bulgarians have yet produced. He is a gifted pupil of the classic masters of many lands.

A somewhat more original and commanding sculptor is Ivan Lazaroff. He has not the perfect technique, the precision, the lightness of touch, the magic delicacy and alluring appeal of Nicholoff — he has created nothing so captivating as Nicholoff's maidens —but he has more power and vigor and aggressiveness. He represents another type and tendency; he creates Bulgarian statues, reveals the soul of Bulgarians in stone and cement images, writes centuries of history into a granite face or hand or headcloth.

His statues are massive, compelling, imperious. They stand out from the others. They tell you of. a nation of burdened, oppressed, half-thwarted men and women toiling up, up, up toward freedom and decent life. He shows you mothers in sorrow, bent women bearing an abandoned people through the ages, strong women with kind, plain, placid faces whose faith and cheer have helped distraught men through critical decades. He places before you small town artisans, hard, diligent, tight-fisted, severe. They sit cross-legged and slowly finger their beads. They solemnly wear their weekly shave. Their sheepskin coats, homespun jackets, baggy pants and clumsy shoes are all in place. Everything is in place. These self-reliant, stern "maistors" resting silently on a, Sunday after an eighty four hours week of work carry the Bulgarian nation on their rigid shoulders. The unyielding lines in their stern faces reveal a resolution and vigor that scorned folly, chased frivolity away, built schools, maintained churches, opened printing offices and gave rebirth .to a crushed people. Lazaroff's simple, ponderous, rough sculpture represents one of the most original expressions of the Bulgarian artistic spirit.

* * *

Now let us look at the painting. Of course, in volume it far surpasses the sculpture.

We shall pass by the rooms filled with portraits and nude figures, not because they are uninteresting or poorly done, but for just the opposite reason, because they are so very well done, because they are like perfectly made portraits and nude figures the world over. There are an infinite number of poses: ladies that are lethargic, and ladies that are tired; there are ladies that allure and others that challenge; some that stretch out their bodies and others that gather theirs up; there is soft fluffy hair that entices and black glistening hair that commands; there are sirens and vamps, sweethearts and wives — as every place else in the world. There are sweet pink and blue dresses, which you would like to have rustle beside you, and dresses that flame and consume; flaunting shawls that rob you of sleep at night, fans that whisper and insinuate, high heels, graceful arched feet, invisible stockings, slender pointed fingers, arms like cold, smooth pieces of ivory, flashing eyes, sparkling teeth and every other appendage that makes women alluring and fateful. There are children and mothers, flabby faced men 'of importance who want posterity to gaze upon their ugly likenesses and grandmas whose kind wrinkled images some one wants to have preserved. Many of them are excellently- done because Stephan Ivanoff, Nichola Marinoff, Nichola Mihailoff, Tsenyou Todoroff, Elena Karamihailova, Mrs. Consulova-Vazova and Boris Mitoff are very talented and skilled in this kind of art.

The pictures representing Bulgarian life, history and fantasies are more interesting and original so let us look at them. In this group fall many of the best Bulgarian paintings, the least valuable of which are those representing war scenes, and the most attractive of which are portraits of folk life — villagers at market, at weddings, dancing in the village squares, celebrating holidays, plowing, sewing, reaping and hauling grain and wood to market. You see the insides of village houses, women at their looms, babies in cradles hanging from the ceilings, mothers rocking other cradles with their feet and managing spinning wheels with their hands, girls cooking over fireplaces and youth gathered for husking or bean-shelling bees. You see madonnas trudging to distant fields with babies tied on their backs; barefooted girls returning from vineyards with great hoes over their shoulders and daisies stuck in their headcloths; grandmas, distaff in belt, taking the geese out to graze; a whole household at noon time squatting under a great, wild, pear-tree eating dinner in the field. You "see men in the village saloon, animatedly talking across a bare table or lined along the walls of the room enthusiastically applauding some more energetic and gifted comrade dancing in their midst. In addition, you see the heroes, prophets and teachers of yesterday — the men who prepared, provoked and managed the revolution which resulted in Bulgaria's liberation. There is the old monk, Father Paissy, sitting in his cell writing the first modern Bulgarian book. Softly the light drifts into his dark room falling upon hands and paper and upon his benign inspired face. It is as the light which he himself brought to his nation sitting in darkness and this painting has moved and inspired whole generations.

These pictures are not masterpieces — such creations are extremely rare in the world — but they are of great artistic value. They express in line and color the sad and joyful romance of Bulgarian life; they perpetuate and glorify past fidelity and heroism; they exalt and beautify the acts, objects and relations that make up every day life; they bring art into common things, crowning them with a halo of brightness and beauty.

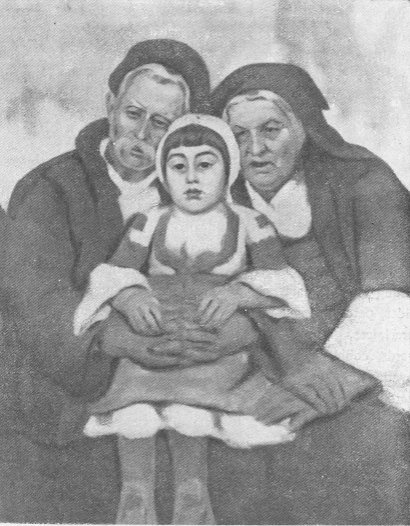

Painting by V. Dimitroff - the Maistor

Grandpa and grandma

One of the foremost of the older artists, devoting their talent to this type of painting, was Ivan Murkvitchka, a Czech who came to Bulgaria shortly after the liberation as an instructor in painting. For years he served as one of the leading professors in the Art School and besides leaving many striking canvases of much worth, he taught painting to two generations of Bulgarian youth. Another one of the older artists who for decades held the first place in Bulgarian art circles and was also for a long time director of the Art School and who did more than any one else to interest the Bulgarian peasant nation in beauty was Anton Mitoff, whose paintings of folk life are still among the very best in the country.

Two other distinguished artists whose talents are expressed in paintings

of this sort are Boris Deneff and Nichola Taneff. Their specialty is typical,

old Bulgarian towns. They paint not so much interiors, scenes and people

as streets, houses, yards and places. They give you towns that are simple

and plain but that have a personality. Old settlements clustered about

springs, strung along streams, chucked into gorges, climbing up mountain

sides, perched on crags, leaning backward so as not to fall over precipices,

grouped about giant trees. You see little, well-swept yards, cobble stone

walks, low, painted mud walls, tiled roofs, overhanging bay windows, well

latticed projecting balconies, verdure creeping over porches, cozy nooks

shaded with aged, gnarled grape vines. You are brought to the dwellings

of the old Bulgarian artisans, on the ground floor of which were shops,

and stores; you see modest homes distinguished for frugality, order and

discipline, with hand'-made rugs on the floor and hand-made pots and kettles

on the shelves, homes of traditions and obligations, that required men

to go to bed and to rise early and not to make love until after marriage.

Taneff has given exhibitions of his paintings in many European countries

where they have been very favorably received. Deneff's are a bit more striking

and vivid, with more life and color — with a little too much color, they

glare too strongly. In addition, Deneff makes drawings of native types

which are certainly among the finest creations of the kind produced any

place.

|

|

| "Spirit and Matter", by Andrei Nicholoff, who has no Bulgarian rival in the grace of his lines and the fineness, accuracy and exquisiteness of his forms | A drawing by Boris Deneff

|

Naturally, the Bulgarian mountains, gullies, rivers and crags attract many artists, and there are a number of excellent landscape painters, none of whom are better than Nichola Petroff and Constantine Shterkeloff. Probably no Bulgarian painter has so good a right to be placed among Europe's best as Petroff. He died young, a victim of privation and tuberculosis, and never reached the full expression of his genius but his pictures of Bulgarian scenery have never been surpassed. Since Petroff's death Shterkeloff has held the first rank.' For many years he was very active, spending much of his time in the midst of nature and giving exhibitions of new creations almost every season. And invariably his work has provoked the highest admiration. His delicate, accurate coloring, perfection of details, precision of form and the grand sweep of his views give his work a special place in Bulgarian art.

* * *

An inexhaustible source of inspiration for artistic creations is furnished by Bulgaria's historical legends and mythical fantasies. The arrival of the savage old Bulgarian Kings in the Balkans who came from no one knows exactly where and represented no one knows exactly what. Their conquests, crusades against the Byzantine Empire and dramatic acceptance of Christianity all afford rich material for striking paintings, while even more fascinating and romantic are the fairies, nymphs, dragons and devils in Bulgarian myths. Descriptions of the character and acts of these legendary beings are preserved in Bulgarian folk songs, for the Balkan world has always been filled with spirits and animated by marvelous, miraculous deeds. Many are the dark woods, the deep defiles, little level grass plots, challenging boulders and foaming waterfalls where nude fairy maidens hid or danced or bathed and where dragons lay in wait for hapless damsels. The sun himself was an extremely popular legendary hero and performed many astounding exploits. In addition, there was King Marko with his faithful charger "Spot" and the adventures of this lusty pair alone, as related in some of Europe's finest folk songs, would keep all of the present generation of Bulgarian artists busy until the end of their days. Marko has inspired one of the most striking statues of the greatest sculptor in southeast Europe, the Croatian Ivan Meshtrovitch of Zagreb, and has enjoyed the attention of many Serbian artists, as well; so naturally the Bulgarians, considering him their special hero too have not been tardy in putting onto canvas his giant horse, monster sword, fierce countenance and domineering, good natured, futile swagger. All these pictures give wide scope for the play of the artists' imagination and are among the most interesting of the Bulgarian paintings. The men who have done the best work in this field are D. Geudjenoff, Nichola Kozhouharoff and the late Ivan Mileff.

Painting by Nichola Kouzhoharoff

When I look at this painting I can’t help but regret

that I didn’t get my wife that way – a-stride a white horse, with a gay

handkerchief waving from its bridle, and surrounded by bold companions

to save me from irate, vengeful brothers and furious rivals. Such stealings

still happen but they are as dangerous as romantic since the Bulgarians

shoot very straight

The Bulgarians have a number of very clever and gifted caricaturists of which the best are the veteran Alexander Bozhinoff, and a beginner Iliya Beshkoff. For years Bozhinoff was unrivaled in this field, forcing under the yoke of his caustic pencil all persons of prominence. His gallery of cartoons with the exceedingly clever remarks beneath them would constitute a political and social history of Bulgaria. No one is spared, from King Boris down to the simplest villager. It is astounding what apt portraits Bozhinoff can make with a few strokes and a couple of curved lines.

Not much inferior is Beshkoff, a youth who only recently began to draw. His work is a little more grotesque than Bozhinoff s as well as somewhat more satirical and biting. It also appears to be a little cruder and clumsier, but that is in reality a studied effect. Beshkoff likes to produce the impression of simplicity and naturalness. His pictures look as though drawn by children. But they are admirably done, very striking, full of expression and vitality and amazingly like the persons whose features they distort.

In the field of graphics two artists have won high places, Vasil Zaharieff, one of the most distinguished professors in the Art Academy and Peter Morozoff. The latter confines himself almost exclusively to etchings and his pictures of Bulgarian scenes, places, buildings and types are known to foreigners visiting the country. His lines are accurately drawn and his colors delicate and harmonious. Zaharieff does etchings and is, as well, the chief wood cut artist in the country. In this branch of art he is the successor of the old Bulgarian eikon, or saint, makers who also worked on wood. The craft was passed from father to son so that a few gifted families made most of the best Bulgarian religious pictures used in churches and homes. Zaharieff's specialty, however, is not religious art, but the reproduction of typical Bulgarian scenes; that is his best wood cuts are pictures of old streets, churches, picturesque houses, monasteries, people and scenery.

The decorative artists of outstanding ability are Nicolai Rainoff and S. Badjoff.

Two Bulgarian painters enjoy places apart: they are Vladimir Dimitroff -the Maistor and Boris Gheorgieff. Dimitroff has worked out a form and method all his own. He spurns color and greatly simplifies his forms, avoiding flourishes and superfluous lines. His figures appear stereotyped and symbolic. They are rather unreal and mysterious, not a little formal and stiff, yet full of meaning and expression. They are types, apocalyptic signs; they are voices, spirits, qualities, truths.

No less original, though more versatile and gifted is Boris Gheorgieff, who is both an excellent portraitist and a mystic symbolist. His pictures are drawn and painted with unusual precision and delicacy, revealing an admirable technique combined with a freedom, a fantasy and lightness of touch found in no other Bulgarian artist. There is much otherworldliness in Gheorgieff's work, much spirituality and aspiration. He uses soft golden tints, diffusing brightness and sunshine. In many paintings the light is somewhat suppressed or just emerging. There appears to be far more in these pictures than you see. You feel that you are looking at them through a veil and that they lead to some distant realm of quiet light and rest and purity. Gheorgieff's work bears the quality of purity, of marked refinement, of a tranquil, gentle victory over coarseness and ugliness. His pictures have nothing specifically Bulgarian about them but are the creation of a gifted personality seeking the solution of ultimate problems in a mysticism that is not free from weirdness but is innocent, delicate and exquisite.

This is the scope of Bulgarian' painting and sculpture, ranging from the heroic, massive stones of Lazaroff, portraying baggy trousered artisans, to the fine, barely visible, spirit lines of Gheorgieff revealing white-robed children in an imagined paradise where lions and lambs feed together. So far they have produced no name of outstanding world renown but have made a very creditable record. They have existed barely half a century and without doubt their golden age lies ahead.

by P. P. Morozoff

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]