A political crisis. The government has resigned with an opposition party chief trying to form a new one. The crowd is impatiently waiting before the palace in order to learn who the lucky members of the new cabinet are to be

CHAPTER XIV

Bossing one another

The Bulgarians are a democratic people with strongly individualistic and communal tendencies and the vehicle they have chosen through which to apply their principles is a constitutional monarchy. It is proving to be no worse than most other forms of governments and better than many. The Bulgarians have been wise not to attempt a republic. Any one who has observed the pathetic attempts that various social groups throughout the world are making to manage themselves has no illusions as to the magical endeavors of any special form of government. Almost every one is as good and as bad as most of the others. Bad rulers are able to exploit nations with the best of constitutions and good rulers can employ even the worst of constitutions for the benefit of their people. The constitution which Bulgaria uses is one of the best.

It is very radical and very "advanced". This corresponds to the national character and especially to the convictions of those Bulgarians who did most toward the liberation of their country. It is to be remembered that revolutionists were largely responsible for the creation of the constitution and, naturally, men who had suffered greatly at the hands of foreign tyrants and domestic stand-patters were determined to make their new state as "democratic" as possible. They wanted to render it "despot proof", so to arrange it that no oligarchy of "chorbadjias" would ever be able to lord it over the people. The revolutionists believed that a small group of wealthy Bulgarians with "Byzantine" habits had aided the Turks in their age-long tyranny and they wanted to prevent such persons from controlling the new state.

They placed the country in charge of a single legislative assembly elected every four years by all the adult males. This "Narodno Sobraniye", which means People's Assembly, is the supreme authority in the land. It has a president or speaker, who is a mere parliamentary officer, directing the debates and discussions, and ten ministers who are the real rulers of the country. The ministers have a chief, known as the Prime Minister, or the Minister President, who is legally responsible for governmental policy.

However, he is not always actually responsible. There is another supreme factor in the state which often exercises more authority than the Prime Minister and that is the King. Yet the King is not legally accountable. For his acts and decisions it is the ministers who must answer. This does not mean, of course, that the King has unlimited power. Far from it. He is absolutely helpless unless his ministers sanction his decisions. A measure of the King is valid only when signed by a minister. Otherwise, it is as worthless as any other scrap of paper.

Nor can the King, in theory at least, choose his ministers. The people elect their representatives and automatically the head of the largest group in Parliament has the right to be First Minister. He is called by His Majesty and authorized to form a cabinet. With this mandate in his pocket he goes back to his party club, consults with his colleagues and comrades and forms a list of prospective ministers which he presents to the Sovereign, who in practically every case. gives his approval, signs the necessary paper and empowers the new Ministerial Council to govern the country; whereupon it takes the oath of office. If the King should refuse to accept the list of ministers, then the prospective Prime Minister would lay down his mandate and instruct his party, which is in the majority, to vote "no confidence" in any other government the King might attempt to bring into being, thus causing the dissolution of Parliament and new elections. So the "irresponsible factor", the King, is under the constant control of the people. His function in a constitutional monarchy is to give stability to the government and to guarantee continuity, permanence and an even balance of political forces.

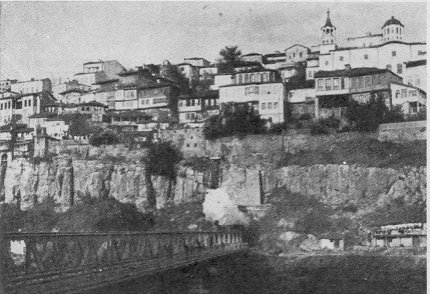

A political crisis. The government has resigned with

an opposition party chief trying to form a new one. The crowd is impatiently

waiting before the palace in order to learn who the lucky members of the

new cabinet are to be

This is, of course, essential in a country like Bulgaria where the electorate is inexperienced and rather ignorant and where violent party passions rage. It was a dangerous venture half a century ago to place a new state in the hands of an ignorant mass of peasants, who had never voted in their lives and who were led by fiery, bold and captivating rebels. Having' suffered 500 years from their rulers, the Bulgarians were by tradition and sentiment against the government. They were hostile to the state machine and its representatives. And there was no one and nothing they so enjoyed singing about as "haidouks", that is Robin Hoods who went into the mountains to shoot the sheriffs and the rich people, namely the pillars of ordered society. And in addition to this traditional tendency toward insurgency the Bulgarians are rather restless, radical people, eager to effect great reforms and to try grand experiments. So a constitutional monarch has been a very useful part of the governmental system. He becomes experienced in the art of governing, is above petty party politics and for many reasons is actually closer to the masses of his people than most political demagogues, so it is to him that the nation usually looks in times of crisis and danger.

Bulgaria has had three royal rulers, two of whom were kings and one a prince, since in the beginning the newly liberated country was given only the rank of a principality under the suzerainty of Turkey. This was a formal arrangement made by the punctilious European diplomats in order to save the feelings of the Sultan, who was grieved at losing his choicest European province. The first ruler, Prince Alexander Battemberg, a cousin of the Russian Tsar, was invited by the Bulgarian Constituent Assembly or Grand National Assembly in 1879 to come to Sofia and accept the Bulgarian throne. He accepted and reigned during a number of very difficult and turbulent years during which he suspended the constitution, led his adopted nation to overwhelming victory in a very decisive war, fell under the influence of poor advisers, was kidnapped and forced to abdicate.

In 1887 after a short interregnum Ferdinand, a young Prince from the house of Coburg, a noble Austrian Family, was invited to become the ruler of Bulgaria. Hs accepted and remained in power until September 1918, when as a result of Bulgaria's catastrophic defeat in two wars he was forced to abdicate and flee abroad, since when he has never been permitted to set foot on Bulgarian soil. Ferdinand, a strong and vigorous personality, usually insisted on having his own way and so completely dominated Bulgarian politics while he occupied the throne that his reign is characterized as a "personal regime". It is certain that he ruled as well as reigned.

He was very able, ambitious and hard working and dreamed of making Bulgaria not only the most advanced, prosperous and cultured land in the Balkans but also the largest and most powerful state in southeast Europe. However, he proved himself a less it prescient statesman than the complicated and dangerous Balkan situation required and placed his people on the wrong side in two unfortunate wars which ended so disastrously that most Bulgarians are inclined to look upon his reign as a calamity. Yet, it is not unlikely that any other ruler in his place would have done the same thing and it is certain that for a quarter of a century he led his people forward with unusual rapidity, winning the admiration of the world, and that he was responsible for the creation of many very useful institutions. It is probable that when history balances Ferdinand's account it will credit him with many things very well done, one of which was the throwing off of Turkish suzerainty and the transforming of Bulgaria into an independent kingdom.

Tirnovo, an old Bulgarian capital

But, whatever that verdict may be, it is certain that his son, Boris, who succeeded Ferdinand on the throne at an extremely perilous and unsettled moment, when Bulgaria was actually at the beginning of bloody civil turmoil, as her soldiers returned bitter and rebellious after a crushing defeat in the World War, has been an exceptionally good ruler. He is without question one of the best kings in Europe. By avoiding all pomp and ostentation, by the quiet display of unusual bravery in times of need, by meeting many very dangerous situations with resolution and unfaltering faith and by solving a long series of acute crises with tact and patience, King Boris III, who embodies all the personal qualities which his people admire, has won the devotion and affection of the nation.

One of the characteristics of Boris which the Bulgarian people most appreciate is his strict economy. This peasant nation is by nature and tradition frugal. The avoidance or waste and extravagance is a religious principle with them. It has been observed by so many generations that a Bulgarian's conscience hurts him when he sees money wantonly squandered. He is inclined to give his admiration and esteem not to the person who can make a big show but to the one who is modest, cautious and self-restrained. And a succession of very hard years, resulting from the wars and the world economic crisis, has made the Bulgarian more prudent than ever. So he is very fortunate in having a king who respects this national trait. Boris has permitted himself no lavishness of any kind. He has been the personification of that quality which all the Bulgarians most highly extol, "skromnost" or modesty. He has surrounded neither his person, his palace nor his work with the slightest pomp and avoids every semblance of swagger and flourish. He inherited from his father a palace in Sofia, another on the coast of the Black Sea at Euxinograd and one in the mountains near Cham Korea and he keeps them up, but has not made any of them at any time the center of expensive or showy entertainments. During most of his reign he has lived very humbly at Sofia with his sister. Princess Eudoxia, whose character, grace and quiet efficiency are models for all Bulgarian women. Only rarely has the Sofia palace been all lighted up and made to echo with the sound of gayety and festivity and on most of such occasions the guests honored by this hospitality have been members of parliament, professors, students or others of the king's own subjects.

Painting by D. Geudjenoff

King Boris I, having been converted to Chrisrianity sends

out missionaries to preach to his people. A millennium ago

Since mounting the throne Boris has undoubtedly led a rather lonely life. His position as king does not permit him to enjoy the intimacy with his fellows which brings inspiration and cheer to humbler people and until recently he has had no family of his own in which to confide, while but few royal guests have visited him from abroad. He has spent much of his time in tending to business of state, in visiting all parts of his country, in receiving the native and foreign officials, with .whom it is necessary for him to confer, and in attending various official functions. Nor has he sought relief from this rather tedious and prosaic life in the slightest excesses, indulgences or prodigality. On the contrary, he has been one of the most exemplary characters in a land of puritanic traditions. He has allowed himself absolutely no favorites and has kept his palace utterly free from back-stair influences. There are no courtiers in Bulgaria. There is no way to get special favors from the king. Although the traditions of 500 years of bondage under corrupt and capricious sultans have made certain Bulgarians too inclined to try to secure special privileges, no one has ever succeeded in carrying that practice into the palace. There everything is straightforward and done according to the rules. Prime ministers need not fear that King Boris or any of his household are intriguing behind their backs, while the opposition, on the other hand, may be sure that if the occasion warrants, it will be permitted to go pass the main gates (through the front door into His Majesty's cabinet.

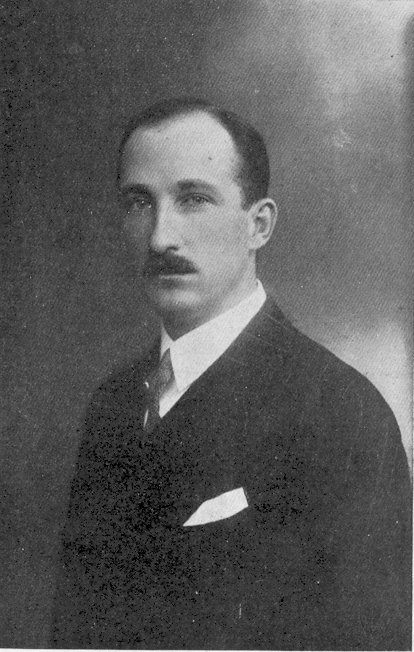

Queen Ioanna

King Boris III

This patience, tolerance, and probity, so characteristic of King Boris, is seen especially clearly in his dealing with condemned civil and political criminals. Since two elaborate and serious attempts have been made on his life by "reds", one might suppose that he would be rabid toward them and fanatically inclined to root them out. But what he has actually done is to prevent the execution of practically every death sentence pronounced on communists and political rebels and he has even gone so far as to free many of them from prison. Boris has much poise and self-control and seldom becomes rabid about anything. He annually releases a large number of prisoners from the penitentiary, so that practically no condemned person remains in jail more than fifteen years.

In his contacts with his people the King is very cordial and genial. The number of them whom he knows personally is surprisingly large. He is acquainted with practically every one in the country who has distinguished himself along any line. He has an excellent memory and when reviewing the long processions of professors, teachers, students and citizens belonging to hundreds of organizations, that occasionally pass through the palace yard he nods at many humble marchers whom he has met at one time or another. And it is notable that on such occasions as these King Boris does not "receive" the processions from a stand or balcony or astride some big white horse but standing on the ground beside the road along which the people pass. There are no barriers between him and his subjects; no soldiers, policemen or formalities separate him from the nation over which he reigns. He meets them face to face, all standing upon the ground and he often pats the heads of little children passing by or permits old bent grandmothers to stop, kiss his hand and give him their blessings.

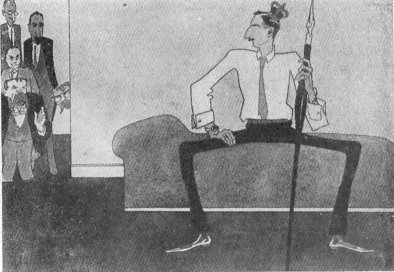

King Boris, as the cartoonist, Alexander Bozhinoff, saw

him. The politicians are peeking through the door to see whether or not

His Majesty will sign the bill

Equally pleasant contacts between Boris and his people are made when the King travels throughout the country in his car. Many are the pedestrians to whom he has given a "lift". By no means rare is the chauffeur whom he has stopped to help. On at least one snowy day he helped push a stranger's car through a big drift in which it was stuck and more than one driver who has come to know the King on such occasions has later been surprised to hear His Majesty greet him with the words "Hello, Colleague". One dark night an American teacher driving a Ford car not far from Sofia, changed a tire in the glare of His Majesty's lamps, for coming upon the flivver stranded beside the road, the king had his chauffeur stop and turn his lights on the disabled wheel. A multitude of kindly, homely acts such as one brotherly person does for another have endeared the Bulgarian King to his people. The fact also that Boris is an expert engineer and that he often drives the train in which he rides has aroused more esteem for him among the common people than any amount of pomp and ostentation would. Practically all of them work with their hands and when they see their King dressed in overalls and engaged in rough toil which requires skill and strength they feel a strong bond drawing them to him.

The King's personal appearance also strengthens the confidence which his subjects have in him. His face, bearing and attitude inspire good will. He is fairly tall and a trifle stooped; his face is rather thin and long with a prominent Coburg nose; the seriousness and wistfulness of his countenance are often brightened by a friendly smile. He gives the impression of being rather bashful and on solemn occasions looks earnest rather than pretentious. He is an excellent soldier and gives much attention to his army which he considers a vitally important institution but he has not a military bearing. He rather makes one think of a professor or judge or business man, the sort of person who would be a good neighbor and who enjoys the pleasant things that make most of us happy, even though he is under the weight of a great responsibility.

Due to these qualities Boris has come to be the greatest political factor in Bulgaria. He very scrupulously observes all parliamentary forms and occupies only the place which the constitution assigns to him but because of his ability, wisdom, experience and force of character he is coming to play a decisive role in the affairs of state, which is without any question for the best interests of his country. No one accuses him of maintaining a "personal regime".

One of the best things which King Boris has done for his people was the recent bringing of the Italian princess Giovanna to Sofia as Queen; she is the first that Bulgaria has had since Eleonora, the second wife of Ferdinand, died on the twelfth of September 1917. It took the young King of Bulgaria twelve full years to secure the kind of a bride he wanted. When he mounted the throne, hastily left by his father, he was 24 years old and when he married on the twenty-fifth of October 1930 he was 36. His bride is 23. The principal reasons for this long delay were the unsettled political situation of Bulgaria, the rather indefinite relations existing between it and most of its neighbors, the somewhat unstable position of the throne during a number of years, the religious hindrances always standing in the way of a union between an Orthodox groom and a Catholic bride and the difficulty of effecting the sort of a political alliance that Bulgaria sought in the person of its new queen. But by long and patient efforts Boris, aided by his ministers and people, succeeded in establishing order and tranquillity within and good relations without, in creating a benevolent attitude among the Great Powers toward Bulgaria, in gaining the favor of the Italian government and in winning the consent of the Pope to a mixed marriage. Even before that he had seen to the still more essential preliminary of capturing the heart of Giovanna, the daughter of the King and Queen of Italy, and one of the most charming princesses in Europe. It was only her heart that Giovanna could give, for her hand was controlled by all powerful and slow moving religious and diplomatic authorities. But they also gave their consent at last and on Friday evening the third of October the Sovereigns of Italy announced in Rome that they had betrothed their daughter to the King of Bulgaria. The news did not reach Sofia until the following morning when it was immediately disseminated throughout the whole country, soon reaching even the most obscure village and causing sincere and hilarious joy. At no time since the close of the war have the Bulgarian people from town and village, simple and educated, rich and poor, been so exuberantly and expressively happy as they were on the day they learned that their king was engaged to Giovanna. The whole nation gave itself up to festivities and rejoicings, joining hands and voices in national songs and dances. That day the Bulgarians forgetting hard times, political enmities, personal grievances and reforming missions, made their land beam with smiles and vibrate with the sound of old betrothal songs and the tripping of moccagined feet.

Three weeks later Boris and Giovanna were married according to Catholic rites in the little Italian town of Assisi, made sacred and famous by one of the world's most lovable saints, to whom the bride is especially devoted, and immediately afterward the couple left on a special boat for Bulgaria where their arrival on the thirty-first of October provoked extraordinary demonstrations of joy. The King and Queen went directly from the Sofia railway station to the great Cathedral, the most imposing church in the Balkans, where the royal couple was blessed in the presence of the most distinguished representatives of the nation. This was technically not a wedding but the service very much resembled an ordinary Orthodox marriage ceremony so the Bulgarians universally speak of it as the king's wedding. In this way both Catholic and Orthodox religious sensibilities were satisfied and on one little front at least peace without victory was reached between the eastern and western churches, which for more than a millennium have been in bitter conflict in southeast Europe. The question of the faith of the children of this Catholic mother and Orthodox father still remains, but it is almost certain that the firstborn boy, the Crown Prince, will be baptized by Orthodox priests and if the other children are Catholics most Bulgarians will not seriously object. After the ceremony in the cathedral the King and Queen went to the palace, Giovanna, now Ioanna (Jenny), entering it for the first time and there in the courtyard for three successive days they received the people who marched through to congratulate them.

The Bulgarian people are very much pleased with their new Queen. One reason is that they wanted their lonely King to have a companion and normal domestic life. The family is one of the most fundamental and sacred of Bulgarian institutions and no ties are so strong as those between relatives. Betrothals and weddings are the most important occasions in the life of the people, who always celebrate them with a great deal of lavishness and happiness. Naturally they wanted to see their king experience this greatest of Bulgarian joys. And they could not but love the woman who brought it to him. A bride always brings happiness to a Bulgarian village and since Ioanna was the whole country's bride she made everybody happy. Besides this, the Bulgarians want children in the palace, they want to have the dynasty strengthened by an heir. In addition, this dynastic union with a first rate country, such as Italy, has brought the Bulgarians much satisfaction, for they feel in a way that they have married into a cultured and a very influential family.

A wedding present given to the king and queen by the

national representatives. It is a large golden bowl designed by the artist

S. Badjoff and made by Sofia artisans

But most important of all, the bride impresses the Bulgarians as being just the kind of a queen they want. She seems to have many of the qualities that have made Boris so popular. She is girlish, rather bashful, delicate and demure and apparently free from all pompousness and love of ostentation. Fragile and finely formed she seems ethereal and exquisitely romantic, the sort of a royal bride that one might read about in a fairy tale, She is also serious and wholesomely religious and from the very beginning has shown an intimate motherly interest in her new peasant people. She has stood many hours beside her husband to greet endless masses of common folks that marched by and has been eager to meet as many of them as possible. As she has come in contact with the ministers, Congressmen, teachers and villagers Boris has always presented her simply as "my wife", according to the ways of ordinary folks, and this cordiality and lack of pretentiousness has drawn the people to her. If the apple cart were overturned and a king and queen were elected in Bulgaria it is certain that Boris and Ioanna would be chosen by acclamation.

Sovereigns, however, are not elected, though they are practically the only authorities in the country who are not. The people vote for all their other officials from the highest to the lowest. They begin with the village and town councils or the heads of the communes, of which there are 2,659 in the country, 93 of them being urban and 2,566 rural. The discrepancy between the number of villages in Bulgaria — 5,700 — and the number of village communes — 2,855 — is due to the fact that settlements containing less than 100 houses cannot form separate self-governing units but must combine with one another or with larger villages. The rural councils are chosen every two years and the urban councils every three by secret voting in which each male "over 21 years of age participates; gypsies only are excluded. The councils in turn elect the mayors' helpers and mayors, who receive salaries ranging from ten dollars a month in the smaller villages to 175 dollars in Sofia. School trustees are chosen in the same way and are responsible for choosing the primary school teachers. The people also elect the priests and the Church trustees.

The next highest administrative units with elected officials are the sixteen "okrugs" or counties, each of which has a county council that meets once a year and functions as a little parliament; it is directed by an executive committee of three paid members receiving salaries of from 75 to 100 dollars each monthly. The central government also has a representative in each county, namely the "county governor" or prefect who is a very important state official. In the name of the minister of the interior he controls the acts and decisions of the communal and county councils and preserves order in his district. One of the chief .functions of the county governors is to direct the state police and it is they whom unscrupulous governments used to employ to "make the elections". Fortunately this practice is being discontinued.

In theory Bulgarian elections are very fair. The laws regulating them are exemplary and as near abuse proof as it is possible to make them. The president of the election bureau is a neutral person and the electors, after having entered a secret booth where they put their ballot in an envelope and seal it, hand it to the president and watch him as he drops it into the urn. No armed persons are allowed in the poling place and no electioneering is permitted in the yard surrounding it, while watchers representing the various parties are authorized to exercise whatever supervision they may wish. Every precaution is taken to secure absolute fairness and although local intimidation still occurs, the central authority through the county governors has succeeded in putting an end to most fraud and violence. Graft and force were the most effective factors in the Turkish Empire and as such tended to enter into Bulgarian political traditions, so it is very commendable that the country has passed from "managed elections" to a fairly free expression of the will of the people. A rather complicated system of proportional representation exists.

The most bitter partisan struggles of course center about the general or legislative elections which take place every four years, for the men then chosen are the real rulers of the country. They meet once annually in a session, lasting from the twenty-eighth of October to the same day in March, which is held in the National Assembly at Sofia. It is a fairly large, not very imposing building in the best part of town and contains many offices and committee rooms, a restaurant and reading' rooms, besides the assembly hall, which has a raised platform, bearing a throne, from before which the king annually reads his royal address, and tables behind which sit the speaker or president and his assistants. Below this stage and facing the hall is a tribune's desk or pulpit situated on a low platform which each deputy mounts when he wants to make a speech; in front of that and facing in the same direction is a semicircular bench behind which sit the ten ministers. Facing these are a dozen semicircular rows of benches for the 274 deputies or assemblymen. To the right of the president and the throne, facing them, sit the members of the conservative parties or "rightwingers" and on the left the radicals or "reds", popularly known as "left wingers". Political passions run high in Bulgaria and the sittings are often stormy. Generally speaking the cabinet members are subject to much stricter parliamentary control than in America for they attend the sittings regularly and are faced by all the assemblymen, who frequently give them questions and interpellations, in the presence of the whole nation, calling them to account for what they do. The men who made the Bulgarian constitution ardently believed in democracy and created a state machine to be run by the people — or their political bosses.

The cabinet is made up of the following ten members: Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of the Interior, of War, of Education, of Agriculture and Public Domains, of Public Works, of Justice, of Communications, of Industry and Commerce and of Finances.

National assemblymen receive 90 dollars a month and the ten ministers get 200 dollars a month each. The country governors have a salary of 80 dollars monthly while the judges get from 30 to 90 dollars.

An "Okruzhen Palace", the seat of the local government

in one of Bulgaria's sixteen counties

And for this very small pay the latter render excellent service. Political passions at times creep into most branches of the state service but the courts are remarkably disinterested, efficient and impartial. They keep public justice on a very high level. There are conciliatory courts in every city and large village, county courts in the sixteen counties, three courts of appeal and a Supreme Court. The jury system has been discontinued for it has been found from experience that three trained judges give fairer verdicts than peasants or small townspeople filled with local prejudices and moved by political or class bias. The prisons in Bulgaria are not pleasant places to fall into but several new ones have recently been constructed answering all the requirements of the newer tendencies in jurisprudence and in the treatment of criminals. The Bulgarian police has been much improved during recent years. Unfortunately it still uses very brutal methods. Still more unfortunately, most of the drastic practices it employs are in no respect specifically Bulgarian. The police of practically no other state, except Great Britain, can throw stones at it.

Bulgaria is not an ideally governed land. What country is? There is much bureaucracy in the administration, not a little favoritism and some corruption. A visit to Parliament leaves the impression that the law-makers are not very wise and not completely disinterested — in a word, they are like most politicians the world over. Nevertheless, the democratic experiment has justified itself. in spite of all its defects, the Bulgarian state machine is the best in the Balkans — it is the least corrupt, grants the most freedom, is the most stable, is most subject to popular control and least absolutistic. It could be vastly improved and probably will be in time.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]