Painting by Arie Kalucheff

Mother puts her famly to bed; she'll soon crawl in beside them

CHAPTER XVI

Making things

B.

Pottery making was another handicraft carried on by thousands of families. Its products were ever in demand for they have always formed an essential part of the furnishing of most village homes. The women often bake bread in large round, thick, flat earthen trays. They place these on the hearths, put the bread in them and, covering them with close fitting arched iron lids that leave plenty of room for the bread to rise in, they completely submerge it all under coals. Thus without any stove or the semblance of an oven the Bulgarians can make excellent bread.

The "geuvetch" is another very indispensable Bulgarian utensil. It is a large flat bottomed crock, usually brown in color. On holidays it is filled with rice and meat, or with an assortment of vegetables and meat and carried to the public oven where its contents are baked. "Geuvetches" which are usually very peppery, are among the most popular of Bulgarian dishes.

Every variety of jugs or "stomnas" is used. Many of 1hem are delightfully colored and gracefully shaped. On them is lavished most of the masters' skill. The necks are long and broader at the top than at the base, where they are attached to the body. The handles are large and often ornamental with a rather free and easy air, like flying buttresses. A little hole leads from the bowl of the jug to the top of the handle so that one drinks not out of the mouth but from the handle. Some jugs have spouts like tea pots, as graceful as swans' necks, and the little jugs for children serve as whistles, playing a gurgling tune when filled with water.

These "stomnas" are used also in the place of wash bowls. In other words the Bulgarians wash out of jugs, which seems a little bit strange. It is indeed a rather complicated process and always requires a helper, who pours water on your hands. The host does this for his guests, the bride for the groom, the children for their parents, the daugher-in-law for almost everybody else. The pourer holds a towel over her left arm and after she has poured all the water that you want into your hands and you have dashed it on your face and neck and head and stand bent over so that it will not run down on your clothes, she hands you the home-spun, red-barred towel with lace worked into the ends.

Small, spherical pots resembling miniature gold fish bowls are used for fermenting the noted Bulgarian "sour milk" which is used extensively and is reputed to be a remedy for many ills.

Painting by Arie Kalucheff

Mother puts her famly to bed; she'll soon crawl in beside

them

Beans, one of the most highly esteemed Bulgarian dishes, are often boiled in jars that sit on the hearth beside the fire, gently clucking and sputtering. In simple village houses they, as most other victuals, are served from a common pot in the middle of a small round table and each person dips into the central supply with a wooden spoon.

The daintiest pottery products made by the Bulgarians are tiny Turkish coffee cups. The largest creations are great jars half as big as barrels used for holding salted or pickled vegetables and marmalade.

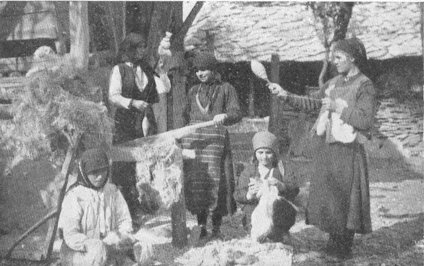

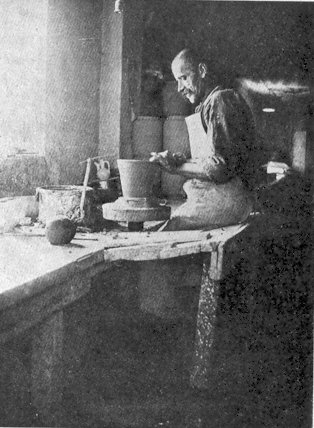

Chopping and spinning hemp for rope

Pottery making in the year 1931 does not differ very much from pottery making in the time of King David. The trade is carried on in the lower stories of small crude workshops. The potter's family lives up stairs; there is a little stable on one side of the yard, a pile of clay on another and the pit or oven for baking the pottery in the middle. In the yard also may be a machine for kneading the clay while in the shop the chief contraption is a revolving table. The master slaps a ball of clay onto it and makes it revolve with his feet, giving the mass any shape he desires as it spins through his skillful fingers. Simple as the craft is, a stranger cannot but marvel as he sees an. amorphous hunk of mud suddenly assume the form of a graceful jug. When a whole flock of these soft, grey objects, looking as timid as new born lambs, have been produced the maistor and his children very carefully put them into the oven where they bake gently for twelve hours. Then he removes them, lets them cool off and paints them, after which he again bakes them intensely for five hours and behold they are ready to be loaded into carts and sent to the markets and fairs.

* * *

These jugs are very often mentioned in Bulgarian folk poetry, because many "little maidens" carried them to the village fountains for water and while there the girls very often chanced to meet handsome shepherds, plowboys and horsemen — sometimes even mountain Robin Hoods — and of course such encounters gave rise to emotions well worth singing about. So a graceful "colored jug" came to be a romantic object. Yet even more alluring were the "white kettles". The jingling of them by the water-girls who carried them on the ends of sticks curved over their shoulders seems to have excited the hearts of village sports beyond control.

Listen, for example, how one youth, Stoyan, expresses himself:

"Oh maiden gay, please run away,

"Don't cross my path by night or day.

"Let rattle not your silver pails;

"They rouse in me but sighs and wails.

"E'en now my heart o'erflows with care;

"To take on more I would not dare;

"Enough my troubles without more —

"Don't shake white kettles past my door".

But the maiden gay took no heed of this moving plea. She continued to swing her white "mentsi" right past Stoyan's gate on the way to the spring and the poor youth's worst fears were realized. He succumbed and sent his mother to ask the maiden's mother if her charming daughter would add her troubles to his and he learned that she would be glad to, for the two were "as much alike as two stalks of wheat, as born twin brothers". And they lived happily ever after.

Another boy's mother in another song sent the following urgent request

over to Lala's mother:

"Dear neighbor, please give heed to me,

"And tell your Lala, beautiful,

"No more to pass beside our yard,

"Before our wide and lofty gate.

"Her white pails let them rattle not,

"Nor scrape against our woven fence;

"Forbid her pound her wooden clogs, ^

"Her wooden clogs upon our walk,

"She's robbed my Vancho of all peace".

From the rest of the song one sees clearly that Johnny really was awfully badly smitten. He could hardly wait for the sun to go down so as to come in from the field and hear Lala's song, and this was especially sad since his mother had picked another girl for him.

But after the conversation between the mothers, Lala's song must not have been so pleasing, for, from then on, she very enthusiastically extolled the joys of the single life, of the maiden with no "in-laws". And although I have the highest regard for "little maidens" and especially for those in Bulgaria, I feel almost sure that this spinster song of Lala's was accompanied by the tantalizing rattling of white kettles in spite of all Johnny's mother's admonitions.

But let it not be supposed that kettles were concerned with romance only. They also filled very important economic and gastronomic roles. Kettle-making has long been a leading handicraft in many Bulgarian cities. It is carried on in little low buildings that resemble small town blacksmith shops in the American Middle West. There is a forge in the center of each shop, work benches along the sides, and a number of low stumps on the earthen floor serving as anvils. Whole rows of these dingy work shops used to be found in almost every mountain town and the quarter in which they were located is almost invariably known as "the kazandjiiska mahala", that is, the kettle makers' ward.

"Little maidens" of Dobroudja go to the well with their

white copper pails

A "kazan" is a very large round, copper kettle, somewhat broader at the bottom than at the top. It is heavy and solid, covered with a thick arching lid and supplied with two massive handles, like a clothes' boiler. It is too big and expensive to be used for ordinary cooking and serves principally for dyeing clothes, distilling various fluids, boiling rose leaves and other similar trades. Many of them are made in the rose distilling district and have given their name to the chief town there, Kazanluk, or Kettleville.

The "mentsi" for carrying water are just like the "kazans", only smaller, and have handles extending over the tops. Many smaller kettles of the same kind are also made for kitchen use.

"Tepsyas" too are one of the choice products of the "kazandjias". They are very large, round trays with narrow vertical rims and are generally used for baking Bulgarian pies, sweets, and shortcakes. They are as smooth and bright and shiny as a mirror and have given rise to the very common Bulgarian expression "as smooth as a tepsya".

Very small, deep bowled, short handled dippers, called "djesves" are one of the daintiest of the "copper-beaters" creations. They are placed in the edge of the coals on a household hearth, after being filled with water, sugar and powdered coffee, ^.d each holds just enough for one tiny cup of black Turkish coffee with a muddy sediment in the bottom and an exquisite bubbly brown foam on the top.

Refreshment holders, resembling tall slender very graceful pitchers with spouts are among the most decorative products of this handicraft, often equalled and sometimes surpassed by candle sticks of plain and of intricate designs.

You may wonder why copper objects are always spoken of as white, thinking perhaps that copper in the Balkans has some special quality. No, it is red there as every place else and when polished looks somewhat like blushing gold. But such a utensil corrodes and affects the food or other material which it contains, so practically all the copper articles are very carefully covered with a thin coating of a shining white solder-like amalgam that when polished looks like new silver.

* * *

Perhaps the most important of the remaining handicrafts was the making of iron. It did not, of course, flourish in every town, since the ore was not found everywhere. But in several centers large quantities of iron were produced. This craft differed from the others in that it was not carried on, in houses, yet it was organized and conducted in much the same way as the others. It was under the control of guilds.

A guild in Bulgaria is called an "esnaff" and an "esnaffer" or artisan is reputed to have been a limited, conservative, strait laced stand-patter; it is said they were puritanical, practical Babbitts. They certainly were not so very gay and frisky and their sons and daughters had to watch their "p-s" and "q-s". Nevertheless, these "esnaffs" created modern Bulgaria.

V. Dimitroff - the Maistor's Mona Lisa

The system they worked out had many admirable qualities. It fostered both democracy and discipline, gave everyone his

chance, placed boss and errand boy on a common footing, encouraged team work, stimulated pride in workmanship and aroused a feeling of social responsibility. Bulgaria will be eternally indebted to those stern, serious, frugal, unbending old "esnaffers".

And it must not be supposed that the handicrafts have vanished. The system continues to exist. There are still thousands upon thousands of small shops; there are master workmen, apprentices and guilds. In villages and smaller towns most of the things the people use are still made by artisans. Nevertheless, western industrialism is causing fundamental changes. Some handicrafts are disappearing before the flood of factory-made articles. Soap making, candle making and stocking knitting have ceased to exist as handicrafts. Rope making and the weaving of goat hair rugs are disappearing; sheep skin caps and coats are giving way to hats and European coats; moccasins to shoes, copper kettles to imported granite ware and wide red belts to suspenders.

It is notable that the masters adjust themselves rapidly and try to create new sorts of articles as soon as changing tastes demand them, so they still beat the factories to many markets. The state also has come to their rescue and it is probable that they will hold their own for many years yet. They are putting up a very stubborn fight. But it is a never ceasing struggle and little by little the capital and science and steam power of the West are supplanting the little shops of independent masters. Industry, the child, is replacing her parents, the craftsmen.

When is an enterprise for making things a handicraft and when an industry? Is it one when you sit cross-legged, making pants sagging in the seat and the other when you sit at a sewing machine making trousers broad at the botttom? Is it one when you make dozens of high sheepskin caps and the other when you make scores of squatty cloth caps? There seem to be other differences too. A manufacturing establishment ceases to be a trade and graduates into an industry when it uses a certain number of workmen and a certain amount of horse power and capital. To hasten this development the Bulgarian state in 1896 and 1906 passed laws "to encourage industry", the encouragement consisting in the raising of a tariff wall against foreign manufactured articles and the giving of certain favors to local enterprises. From time to time since then and notably in 1926 additional privileges have been accorded home industry. And these measures have not failed to .bear fruit. The growth of industry has been fairly rapid and especially since the war. Generally speaking, indeed, industry in Bulgaria is a post-war creation.

Dobroudjan women chat over the spinning wheel

In 1894 there were 72 industrial concerns; in 1911 —345 and now 2,640 of which somewhat less than half are "encouraged by the state". During the period from 1921 to 1927 the production of cotton goods increased eightfold; of linen goods 50% and of copper 300 %, while during the last twenty years the output of sugar and of vegetable oils has increased 1000 °/o, of tiles 1000% and of machine oil 500%. The number of workers in state protected industries mounted from 10,000 in 1909 to 25,000 twenty years later. Each year the products of Bulgarian industry are greater in value than the state budget, namely 50,000,000 dollars. Most of the industries are maintained by foreign capital. The principal ones are the mining of coal and of copper, the manufacture of cement, the production of sugar and various beverages, the making of all kinds of cloth, the tanning of leather and making of leather products, the curing of tobacco and making of cigarets, printing, the production of lumber and of paper.

The creation of a flourishing industry in a new, agricultural land is of course not easy. On the one side the infant concerns have to compete with the persistent, experienced and agile craftsmen and on the other with world industry, well organized, economically managed, aggressive and ravenous for markets. So the Bulgarians are paying dearly for their modern child — industry. Practically all of the new plants form trusts and dictate prices. In addition, many of them are controlled by foreigners and sometimes impose conditions which are embarrassing and costly for the country. In addition, some of the protected industries are clearly parasitical. They will never be able to stand on their own feet and will always be a heavy and useless burden to the people. Gradually a better policy will be worked out and the encouraged branches will be those which utilize material produced in the country, notably agricultural products, coal and textiles. From now on more and more attention will be given to fruit and vegetable preserving, pork and poultry production and dairy products. Bulgaria, as all the other Balkan states, is striving to enter into the circle of the industrial nations of central and western Europe where horse power, science and capital have produced vast wealth, culture, democracy and aristocratic leisure but she, as her delayed companions, finds the gate strait and the way narrow. It is like climbing up a pyramid, all the top places on which are already taken. And since she lacks the iron out of which all the western countries have made the steps by which they have mounted, it is clear that Bulgaria for many, many decades will remain a predominantly agricultural state with an increasing number of useful agricultural industries.

The potter, Bai Ivan, one of the proprietors of the cooperative

"Progress", turns out a flower pot

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]