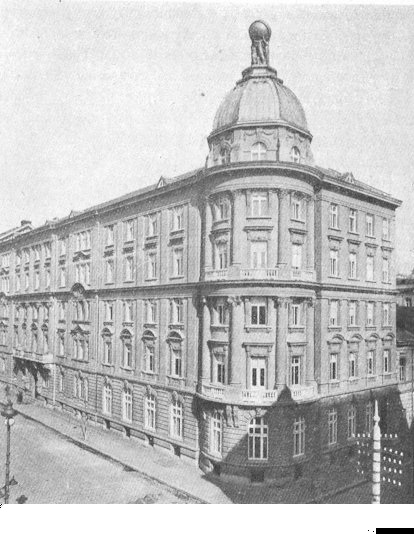

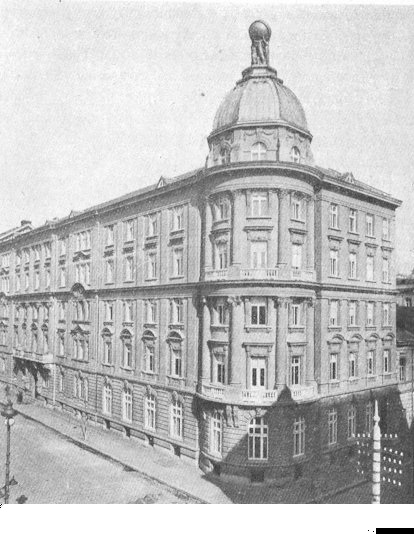

The Cooperative Bank, Sofia

CHAPTER XVIII

Making both ends meet

Before the World War, the whole of Bulgaria, with everything in it and on it, was estimated to be worth approximately two billion dollars, while the annual production of wealth in the country was believed to amount to 330,000,000 dollars. These estimates were based on rather vague data and may have been far from accurate.

Another evaluation made in 1926 placed the total annual income of all the inhabitants of Bulgaria at 40 billion paper levs, or a little less than 300,000,000 dollars.

This would mean an average monthly income of four dollars and a half a person, which would indicate that the average Bulgarian family received about twenty dollars a month at that time. However, this must be taken as the total gross income, and when taxes and operating expenses for farm or factory are subtracted the actual monthly income at present for a Bulgarian family is not much above twelve dollars.

An investigation made not long ago indicates that a family with twenty acres of good land earns not less than twenty dollars a month clear, but the amount of arable land falling to each land owning family is not twenty acres but thirteen, while some families own no land at all.

A distinguished Bulgarian economist. Dr. N. Sakaroff, says that in 1928 a peasant family with twelve acres earned approximately fifteen dollars a month, which certainly means that in 1931 most peasant families were living on no more than ten dollars monthly.

Agriculture, stock raising, woods and home industry account for by far the larger part of the wealth produced by the Bulgarians. Then come business, manufacturing and the trades.

The Cooperative Bank, Sofia

The women of Bulgaria very actively participate in wealth production. Their indefatigable energy is the source of much of the fourteen billion levs coming annually from agriculture. Since they take care of the cows, tend to the chickens and in many cases look after the pigs, not a little of the eight billion coming every year from stock raising is their creation. Practically all of the five billion levs from home industry represent their earnings. And even in some of the heavy industries, such as curing tobacco for instance, the women play a very important role. Women in Bulgaria can do everything from scything, harvesting, plowing and cutting down trees to setting bones, charming away evil spirits, telling fortunes and composing remarkably clever folk songs, and in addition the sacrifices they make to help brothers, fiances and husbands get ahead pass the bounds of credibility, yet the men still speak slightingly of "woman's work" considering women rather foolish and underdeveloped creatures. And strangest of all, the Bulgarian women have accepted this inferior role with astonishing complacency; they really look upon themselves in a rather apologetic manner. The Bulgarians are naturally bold revolutionists and some day before long an astounding new uprising will break forth — when the capable, faithful and diligent Bulgarian women begin to consider themselves full-fledged human beings.

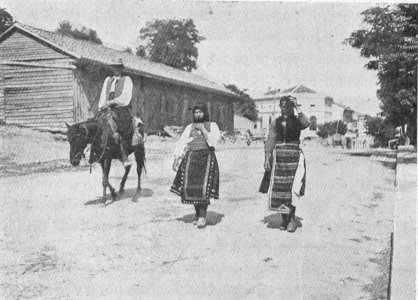

In spite of all her inferiority, however, the woman has won certain inalienable rights which the man dares not take from her, even though he does ride comfortably on the donkey as she trudges along the dusty road with a baby on her back and a bundle in each hand. One such right is that the egg and butter money is hers, as well as most of the cloth she weaves and the clothes she makes. She also has very equitable inheritance and property rights and exercises much influence over family affairs. Though she is not ardently welcomed by her father, is often barely tolerated by her brothers and is completely dominated by her husband she finds much compensation in the love given to her by her unmarried son. For him she is the principal spiritual guide. He holds her in high esteem and sings of her in hundreds of folk songs. In many cases of conflict, indeed, the son favors the mother and neglects the bride. Which is very sad, but let us not begrudge the mother this little bit of belated compensation. The bride will even up the score again twenty years later on her daughter-in-law.

The women walk

And after all there is not much time for sentimentality when you have to make both ends meet on ten dollars a month — even though prices are appreciably lower than they were before the war. Rent for a room in Sofia costs at least four dollars a month though in the villages and small towns most people own their own humble homes. A goose costs from half a dollar down; a chicken, a quarter; a turkey sixty cents; mutton twelve cents a pound; butter, twenty-five cents; eggs two cents each; rice, five cents a pound; beans, three cents; bread, two cents a loaf and coal five dollars a ton. A tailor-made suit of clothes costs twenty dollars, a hand made pair of shoes, three; professional service for ushering a baby into the world two; an operation for appendicitis in the state hospital five and filling a tooth, one. The best seat in the National Theater for a masterly rendering of Tanhauser costs 98 cents and for a presentation of Coriolanus 75 cents. A shave with the conventional fixings costs seven cents; a hair cut ten, a permanent wave three dollars and a public bath twelve cents. Of course, it is not utterly public. Streetcar fare is two cents; a daily paper costs five sevenths of a cent; a movie ticket from twenty cents down and a cup of coffee in a coffee house two cents.

But still the coffee is not as expensive as it might seem, for that two cents includes a free reading of the daily papers — all fifteen of them — as well as a rendezvous with your friends — the intellectuals. They each receive from fifteen dollars a month up, minus ten per cent off if they are bachelors or spinsters. According to the latest table of salaries, the ten ministers receive approximately 200 dollars a month each, with some frosting extra; their executive secretaries — one for each ministry — 100 dollars, national representatives 86 dollars, administrative department heads 60 to 70 dollars, professors up to 80 dollars, with seven dollars a month extra for the rector; supreme court judges get 90 dollars a month and other judges from 50 dollars down. The generals in the army receive 75 dollars and lieutenants 25. The highest police officials get 100 dollars a month, district governors 80 and ordinary cops 13. Archbishops get 100 dollars, bishops 80 and ordinary priests from seven to fourteen. High school principals receive up to 50 dollars a month, high school teachers up to 35 dollars and primary school teachers up to 30 dollars. The head of the Bulgarian railroad system receives 110 dollars monthly, the chiefs of the bigger stations 40 dollars, a train conductor 17 and a locomotive driver the same. A minister representing Bulgaria abroad gets about a hundred dollars a month.

These salaries are certainly very modest, but they are more than the peasants and most of the people in the free professions get, otherwise every one would not be striving to become a state employee.

Practically everybody in Bulgaria pays direct taxes. Only salaries smaller than eleven dollars a month are exempt.

According to Assen Nicoloff, a teacher in the American College at Sofia, "the best way to illustrate the conditions under which a Bulgarian worker gets his living is to compare him with an unskilled worker in America on the basis of the time used in work to pay for different commodities. A worker who would earn fifty cents on hour in the United States, would get only five cents for the same work in Bulgaria. It takes the American laborer twelve minutes to earn a loaf of bread and the Bulgarian thirty-seven minutes. With the pay for an hour's work the American can go to a fairly good restaurant and get a good meal, while the Bulgarian can obtain only a bowl of soup and a pound of bread. For a meal equal to the one the American gets the Bulgarian worker would have to spend the wages of three hours work. While the American puts in forty-five hours of work to buy a suit of clothes, the Bulgarian can have the same kind of suit only in return for three hundred hours of work. A pair of shoes costs the American ten hours of work and the Bulgarian seventy-five hours, presuming he gets the same quality of shoes. For a pound of butter the American works fifty-two minutes and the Bulgarian four hours; forty-two minutes for a pound of cheese, and the Bulgarian two and a half hours, thirteen minutes for a quart of milk, and the Bulgarian one hour. The American worker can buy a Ford car out of his wages for twenty weeks, while the Bulgarian can never think of such a luxury because a Ford car would cost him the wages of five years, working ten hours a day, six days a week".

The annual state budgets are usually about 50,000,000 dollars or 7 billion levs, and have been successfully balanced until 1930/31. The 1931/32 budget in view of the critical economic situation was fixed at 6,400,000,000 levs. Of the state budget Bulgaria spends 14% for education, 17% for the army, and 34% on state debts. The total indebtedness of Bulgaria amounts to 200,000,000 dollars of which war reparations represent 17%. Each year the state pays 2,000,000 dollars against her reparation account. This annual sum will mount to 2,500,000 dollars in 1950 and payment will have to be made until 1966. This, of course, constitutes a very heavy drain on the country. One will find an excellent account of Bulgaria's economic situation in a book recently written by Dr. Leo Pasvolsky and published by the Institute of Economics under the title "Bulgaria's Economic Position". It costs three dollars and contains 409 pages, many of which are not as dull as the title might lead one to suspect.

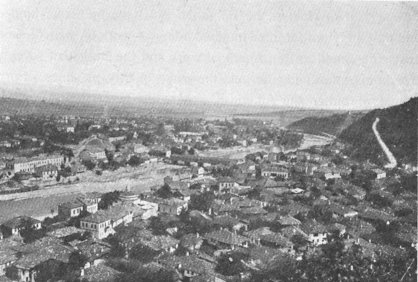

The town of Lovetch, in which is situated an excellent

American girls' high school

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]