All dressed up

CHAPTER III

The People

A.

Of the 5,766,000 people (estimated 1929) that inhabit Bulgaria 520,339 (census 1920) are Turks, whose ancestors established themselves there during the five centuries of Moslem domination. Although comparatively large streams of Turks flowed out of Bulgaria immediately after the liberation of the country, a half century ago, the migration soon stopped and most of the Turks remained where they were; at present their number is increasing rather than decreasing. Bulgaria is the only former Balkan dependency of the Sultans where such a situation exists, which is a striking indication of the tolerance of the Bulgarian people. There are also 42,074 Greeks, 43,209 Jews, 57,312 Rumanians, 11,509 Armenians and 9,080 Russian refugees. Practically all the rest of the people are Bulgarians, who number 4,822,791 within Bulgaria and more than a million outside in adjoining lands and in America.

And who are these Bulgarians? Well, as to that, who are you or any body else? That is, who is an American, or a Frenchman or a Greek? All peoples are mixtures of many racial strains. Pure races do not exist. To describe any nationality group we must draw composite pictures. And the general tags we pin onto nations mean very little.

On the Bulgarians' tag is written the world Slav, which means that they belong to the great family that dominates Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. There are over 150,000,000 Slavs in the world and they constitute the dominant groups in Russia. Poland, Czechoslovakia, Jugoslavia and Bulgaria, The Slavs govern territory 6,763,800 square miles in extent, constituting 12% of the surface of the earth. Their lands in Europe comprise 49% of that continent. Without any question they are one of the three greatest racial groups in the western world, of which the other two are the Latin nations and the English-German peoples.

However, it doesn't mean so very much to say that a racial group is Anglo-Saxon, Latin, or Slav, because local conditions of many sorts exert a stronger influence than blood, and besides the blood in many cases is very thin. A Paris banker is brother to a nomad Vlach shepherd in the Macedonian mountains, Since both are Latins and speak a similar language, but their common Latinity means almost nothing. The Panslav movement and the many congresses of the Latin races are very delightful pretexts for banquets, pleasant trips and eloquent speeches but they rest on meager realities. Slav scholars have furious disputes over the fundamental Slav characteristics and tendencies and are not at all agreed even on the basal question as to whether the Slavs are essentially Orientals or Occidentals, while certain Latin scholars almost completely deny the Latinity of some of their peoples, and who even would dare to assert that the largest of all the English speaking racial groups is essentially English? Is New York an Anglo-Saxon city? Most of the members of the great racial families are only forty second cousins to one another.

In addition to the general feebleness and attenuation of fundamental racial affinities, it must also be pointed out that the Bulgarians are a rather special sort of Slavs — as of course every Slav group really is. They are, in a way, Slavs by accident, or Slavs in spite of themselves. They dropped into a Slavic sea and were Slavized. They went into a strange land and married into a prolific and vigorous foreign family to which they gave nothing at all but their name, and perhaps high cheek bones, dark hair and round heads, which seem to be a little harder, more practical and more obstinate than the heads of most Slavs.

All dressed up

They are rather short of stature, solidly built and dark complected. They usually make the impression of being stolid and are certainly not as volatile as most of their neighbors. They do not seem to be so very easily moved, prefer to conceal their feelings and usually "have to be shown". They tend to be suspicious or incredulous and are very individualistic in their attitudes, are inclined not to lose any opportunities to protest and to criticize and are inexorably insistent in demanding equality, democracy and a fair chance. They are usually eager to see the practical aspect of every situation and manage to turn it to good account. During their whole history they have been more attached to their soil and hearths than to tribal banners and are not among the peoples who make a religion of nationalism. Due to their enterprise, industry and fecundity they have occupied the fertile lands in the greater part of the Balkan Peninsula but they have never held permanent political sway over large areas. In their hearts they seem not to aspire to conquest, in their sad folk songs they do not usually bewail the humiliations of the state nor laud military prowess and when subjected to foreign domination they usually tend to make the necessary adaptations and to continue to subsist even under the hardest of circumstances, learning foreign languages and accepting the most necessary foreign ways. Their supreme loyality through the ages seems to have been to the family and-farm rather than to the army and state.

Yet there could be no greater error than to conclude from this that the Bulgarians are lacking in spirit or that they are without the capacity to suffer for exalted ideals. Contradictory as it may seem, just the opposite is the case. Though insistent individualists, the Bulgarians also have marked socialistic or communal tendencies. A fourth of all their land belongs to the state and communities, and this amount is not being very much reduced in spite of the ever increasing density of population and the hunger of the growing population for fields. The three chief banks are communal entreprises. Forests, grazing grounds, mines and springs are usually inviolable communal possessions. And it is notable that all types of Bulgarians from bootblacks up to professors form associations and leagues to defend common rights and gain common advantages. It is true that these individualistic and cooperative tendencies are in constant conflict with each other, causing the disruption of many organizations and the breaking up of many meetings, but it is the communal tendencies which are gradually prevailing.

And this idealism and loyalty to higher units is also seen in the Bulgarians' religion, for they are decidedly a religious people. It is true that they do not feel the soft, yearning, entrancing, transforming mysticism that moves the Russians, who are the real guardians of the Eastern Orthodox religion. Nor are they subject to the religious emotions which so readily affect the Rumanians, and they have never been so very much impressed by the solemn, authoritative supernaturalness of the Catholic Church. Yet for centuries religion, even though administered by foreign and by no means devoted priests, constituted the chief spiritual and social force operating upon the Bulgarians. It was the principal inspiration and the ultimate sanction in all matters of individual and social conscience.

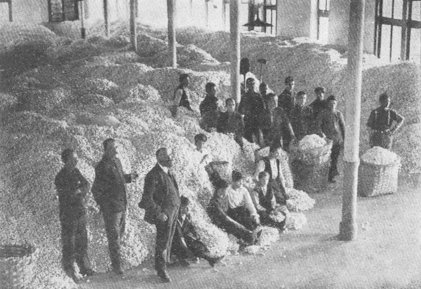

The producing of raw silk is one of Bulgaria's leading

home industries Feeding the silk worms

It is for that reason that there is a church in practically every Bulgarian village — it and the school being almost without exception the two best buildings. The fasts also continue to be kept, the saints' days are observed, candles are lighted and the priest is given his due. The basis of this religious sentiment is not primarily awe nor aesthetic inclinations attracting the people to incense, golden robes and pleasing motions, nor is it a tendency toward theological speculation but rather a love of order, a sense of obligation and a tendency toward wise precaution. Many elements of Protestantism and of the Old Testament Judaism enter into the religion of the Bulgarians. It means playing fair with God, and a peasant people without a belief in God is of course inconceivable, for they see what they consider His acts every day of their lives. God gives them rain, sunshine, rivers and woods and it is only fair to show suitable gratitude for that. Besides, if one doesn't, hail, lightning, wolves, mice and evil spirits are likely to come. So the Bulgarians give unto God the things that are His. As prudent people they could not do less. They know it's useless to try to fool Him.

Then, in addition, the Bulgarians want to have some ultimate factor to enforce morality, maintain the established customs and vouch for the essential equity in the prevailing order of things. Being a rather stern and forceful people with a high regard for the imperiousness of duties, they like to have God stand back of them. They are not afraid of the church, nor are they eaten up by zeal for the house of the Lord; they have not left much property in possession of the monasteries which are now practically empty, nor do they for an instant permit the church to interfere with the advance of science or obstruct the progress of enlightenment. Yet they are deeply imbued with reverence and attached to inherited Christian customs.

* * *

All this, however, is but a feeble expression of the flaming, irrepressible idealism of the practical Bulgarians. Strange as it may seem, these prudent people, largely free from ordinary mysticism, and with little taste for abstract metaphysics give themselves with furious devotion and unexcelled heroism to grand social ideals with a moral aspect. One of the first striking examples of this was the terrific force of a strange, religious movement, Bogomilism, which swept over Bulgaria in the tenth century and was carried from there clear across Europe into France, leaving the graves of martyrs all along the track. It was a revolt against the overpowering authority [of the established church and in many ways resembled a kind of primitive Protestantism. To moral ideals of the highest order and most commendable social requirements it added a grotesque spiritualistic theology, practices of extreme asceticism, shocking ethical emancipation and principles of absolute civil independence utterly contrary to the state, the economic system, the church and conventions. In this movement fearless and fanatical reformers drove certain sound principles to fantastical though perhaps logical extremes. Naturally this precipitated a fearful struggle and the sect was finally stamped out, but not until hundreds of Bulgarians without the slightest hesitation had given it their full measure of devotion.

Picking the silk cocoons

Another illustration of the bold idealism of the Bulgarians in matters of a social and moral nature is the reception which Tolstoy's ideas have been given in Bulgaria. In his attitude toward war, the distribution of wealth, the exercise of authority and moral attainments, Tolstoy was an unflinching extremist, preaching non-resistance, defiance of the state, complete faith in good and absolute love as the guiding principles of one's conduct. These ideals run counter to all established authorities in every modern state and especially in the Balkans, where military service is required and where the state supervises almost every phase of life. Yet in Bulgaria there are thousands of followers of Tolstoy, among whom are the very best youth in the country. They put their ideas into practical application, willingly accept the costliest sacrifices and work with the greatest ardor, in order to help love make a conquest of the world, abolishing boundaries, leveling inequalities, and putting an end to wars.

And in many respects the Bulgarian Communist movement sprang from similar idealistic motives and a similar fanatical zeal. This statement does not mean that I endorse communism nor that I consider the violence of the Bolsheviks in any way similar to the love of the Tolstoyists. But there was much idealism in the Communism which swept across Europe ten years ago. It was a sort of apocalyptic, world movement designed to be carried by ardent apostles over the whole earth, to heal in a drastic fashion all the ills of humanity and to bring in a new dispensation. This made a powerful appeal to thousands of Bulgarian youth, who embraced the movement with fanaticism and spread it as a conflagration throughout their 'country, even to the very last village. They reminded one in some ways of modern Bogomiles and for their misplaced devotion many hundreds of them eventually became martyrs.

With similar enthusiasm thousands upon thousands of the people of Bulgaria have joined the Agrarian crusade and are working to transform their country into a peasants' paradise. This movement has not been so impetuous and revolutionary as Communism but it also has gone to extremes and provoked an opposition that has resulted in much sacrifice, suffering and bravery. And even today, though completely demoralized as a political organization, the peasant movement with its sweeping, radical program is as vital as ever. There is certainly no country in Europe except Russia where so many people have so bravely suffered for world causes which they believed were for the good of humanity as in Bulgaria.

A glacier of silk cocoons

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]