This dining table is not too high even for the smallest tots

CHAPTER VI

Life in the village

One cannot understand Bulgaria unless he knows what village life is like — village life as it has been lived during more than two turbulent Balkan millenniums.

In Bulgaria there are practically no farms. You meet no separate houses sitting modestly though commandingly amid clusters of stables, granaries, gardens and fields. The dwellings are always grouped in villages or towns. Families do not live off by themselves on the land they tend. They prefer to dwell in groups and to go miles daily to work their fields.

There are many reasons for this. The principal one is defense and another one is custom. The land now called Bulgaria was for ages both a highway and a garden. Scores of marauding tribes wandered there taking whatever they wanted and there was much worth wanting. As a result, the natives sought safety by living together in inaccessible places. On the return of more peaceful, times they emerged from the gullies and pushed into the plains but they went together and continued to live in groups. _ A common graveyard, a little church, the advantages of common flocks and common herds, the pleasures of a saloon to meet in, the benefits of working in common on wheat-fields in danger of becoming over-ripe and of husking corn together — added to the prime necessity of a common defense — have prevented the Bulgarian peasants even to this day from moving out of the village onto their land. Newly married couples build their new houses in the village. They like to be with the rest. They want to share in the common things.

This, indeed, is the outstanding characteristic of village life; it makes most things common. It tolerates no secrets, permits no exclusiveness. Sowing and reaping, corn husking and rug weaving, birth and death, buying and selling, sin and frivolity are all communal affairs. The tyranny of the village is inexorable. Rare is he who steals a glance or she who gives a furtive smile in a village. All the peasants know everybody's heart flutters.

For centuries these settlements were both isolated and self sufficient. They were little universes of their own. Nestling at -the base of a mountain, hiding in a ravine or clinging to the top of a cliff, the villages were largely cut off from the rest of the world. There were no roads in Turkey, no regular postal service, no newspapers, practically no books and no schools. Besides, there were brigands and predacious Turks so that it was unheard of for n girl to travel far while even the men were inclined to avoid long trips. When darkness fell, people gathered in their houses and locked their doors. Living on bread, milk, onions, garlic and salt meat in winter and bread, milk and vegetables in the summer, with some sheep's milk cheese and occasionally an egg added, with tea and coffee on holidays, they had no need of going any place to buy their food. All the essentials they had to get from outside were salt, soap and kerosene. But a certain kind of clayish mud very often took the place of soap and wax or grease or pine knots, the place of oil. The men and women both wore pigskin moccasins, both wore sheepskin coats, and both wore homespun, handwoven costumes, while the men wore lambskin caps and the women headcloths. All of these things, except the headcloths and sometimes the dyes for the wool, came from the village itself.

Generally speaking, the whole family slept together in the simple, village houses on the floor: grandpa and grandma, father and mother and all the children, with uncles and aunts not infrequently added. Of course, there was never much undressing. A nightdress was an unknown thing in the villages of the Balkan Peninsula and the women had no undergarments to put on or take off, since they wore their white petticoats night and day. It was only the Turkish women who wore drawers. The Bulgarians were proud that no tightly tied bloomers were required to preserve the fidelity of their wives and daughters. In such a home neither the conception nor the delivery of children was a mystery or a secret. With people and animals living in such close quarters and all abundantly multiplying their kind, the stork theory could not thrive, although there was a stork's nest on every roof. This is undoubtedly the chief reason why sexual matters are so freely spoken of in Bulgaria, causing no snickering and no smirking. The people like children, expect to have them, know how they are made and often tell you they are expecting a baby seven or eight months before it is due to arrive.

This dining table is not too high even for the smallest

tots

Yet, in spite of all this, it is in the old fashioned Bulgarian villages that the most rigid morality exists, that illegitimate children are the rarest, infidelity of women most ferociously condemned and irregularity between brothers and sisters unknown. It is noteworthy that a brother and sister going from the village to the city in order to attend school, often occupy the same room, yet most Bulgarians would consider it preposterous if you were to ask if that was not inadvisable.

Of course, the village as I have described it here is the original mountain village of a century ago or of the time of the American Revolutionary War. Since then there has been much change, much progress. There is no longer such isolation, there is less self-sufficiency and very much less fear. Furthermore, since the wars, progress has become very rapid and in northwest Bulgaria peasant life is being completely transformed. Yet in many places a Bulgarian village remains to a large extent a tiny independent universe.

You may think of it as 200 houses sitting beside a river or clustered about a spring or squatting in a level plain. It usually contains many trees some of which are very old, serving as landmarks and trysting places. They are the grand markers of time; things happened, "when the big tree was just so high" or "before the old tree fell" or »when both of the old trees were standing". The small houses are frail but almost always well roofed with red tiles which stand out invitingly among green branches. The house walls often consist of handmade wicker-work fastened between rough uprights, fashioned by hand with axes or adzes and plastered over with strawfilled mud. Sometimes this is whitewashed but not in all villages. The house contains a vestibule and one room, or a vestibule with a room on each side, while some are even larger. Usually also there is an outdoor covered porch.

In every village, whether the houses are whitewashed or not, there are two white buildings, usually situated above the others if there is an available elevation. They are the school and church. Every yard is surrounded by a fairly high, woven fence, containing as a rule, a large, solid gate, behind which without any exception fierce dogs bark as you approach. And it is best never to defy them. If you want to visit a villager, let him come to the gate to meet you and conduct you through the dog-infested yard. He keeps the dogs to watch and he would replace them if they did not. So do not feel irritated at them for doing their duty. The peasant's hospitality will make up for their snarls and wolfish showing of fangs. Hay stacks, stables, pig pens and chicken coops are found in the yard, which is usually dusty and muddy. In mountain villages there is at least one flat, bare place used as a common threshing floor. In most cases also within a few miles of the village is a stream or spring where the women carry their clothes once or twice a month to wash them. Much more important than this is the place where the village gets its water, for this serves as the youth's social center. .It may be at the river's edge, or at the shaded spring, or at some deep well over which towers the lofty drawing pole, mounted on the top of a high post in see-saw fashion so that as the long, weighted, free end descends, it pulls up a pail of dripping water fastened to the other end. But most frequently of all, the watering place is a "cheshma" which is an ever flowing fountain of water brought down from neighboring mountains through a pipe made of hollowed pine logs joined end to end. Favored are the villages with these ever babbling faucets, which are almost always built by some aged, pious man, who, approaching the grave, wishes to leave some memorial. They are so constructed that the water pours from twin, horizontal, brass spigots under which the girls may place their kettles or jugs. And the fact that they are always beside the street makes it easier for the boys to ride their horses or drive their sheep and cattle up to them, though of course if there were no road at all, the boys would find their way to the "cheshmas" at the opportune time, which depends not upon the thirst of the animals, but upon the arrival of the water-girls.

The milk wagon

Near the village is a common grazing ground and far or near a common forest where every family has a right to get wood for fuel and building. It is due to this cheap material that a bridegroom is able to erect a house for one hundred dollars. And, if the forest is large, each villager has a right to gather wood to sell.

In the mountainous parts of Bulgaria this is the winter occupation. It falls exclusively to the men who leave the women at home to knit, weave cloth, embroider their own and the men's clothes and prepare the bridal chests for growing girls. But in the early spring that work ceases. As soon as the frost is well out of the ground, the whole family goes daily to near or distant fields to plow or hoe or prune the orchards and vineyards. They wake up as soon as it is light, arise from their common bed which is often on a wooden platform raised a little above the dirt floor, and carefully fold and pile up the blankets and the mats. Then the women put on their heavy, black, one-piece dress over their long, thick, white chemises and tie on their short woolen stockings and homemade moccasins, unless they prefer economising by going barefoot; the men put on their equally heavy and very wide and deep seated pants over their white drawers, wrap thick white cloths tightly about their feet and legs and tie on their moccasins which are just like their wives' and sisters', only larger. After that they all go to the yard where someone pours water from a jug or brass kettle on their hands that they may wash, which they do quite thoroughly. Since the men's hair is tightly clipped, they need lose no time on combs

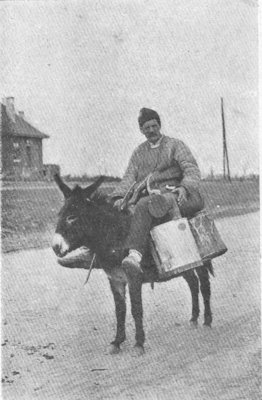

The family washing. No, the lady is not wearing modern

sport pants but has merely tucked her skirt between her knees to keep it

dry

Painted by Anton Mitoff

and since the women's is tightly braided, it requires nothing more than to be covered with a becoming kerchief, dexterously tied. Then both the men and women girdle themselves with very long red belts a foot wide and they are ready for-the day.

Sleepy oxen are driven into waiting yokes, mothers tie the babies on to their own backs and off they all trudge breakfastless to the field. At ten, they stop for a snack of dark . bread and perhaps a little sour milk. At two, if they are not working too far from the village, some member of the family will bring them a warm stew, probably made of beans. On fast days they eat only bread and salt. When the sun goes down, they all trudge back home again, perhaps several families together in a drove and the girls will be singing. Perhaps some woman will be seen riding in the ox wagon all by herself in which case you may know that she is about to deliver a baby. The fields are often very far from the village and oxen, all oblivious of emergencies, move very slowly so there is more than one stalwart man in Bulgaria today, who was born in the field or in an ox cart and on the third day after his most casual arrival he bravely rode back to the field again on the back of his indefatigable mother. Yet, in spite of it, all there are more women in Bulgaria above one hundred years of age than men and of these female centenarians not one is a spinster and most live in villages.

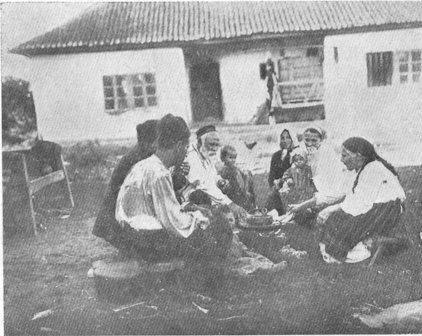

By the time the family returns from the fields the herds and flocks have come back from their pastures and they all enter the yard together — people and animals. The cows or buffaloes are milked, the eggs gathered, and the family squats on the floor about their little low table, noisily to eat a stew from a common bowl, and clickingly to munch vast quantities of black bread. Darkness long ago covered the village and the forms of the animals sleeping in the yard can hardly be seen as the family again spreads out its mats, unwinds its belts, takes off its moccasins, discards its outermost garments and lies down for the night. The little children are not always gathered into the common bed but are allowed to sleep wherever they have lopped down in their weariness. Why should they be disturbed, for it is but a short time until the fast fleeting darkness will have left the village and then they will all have to arise and get under way again.

And some nights there is no returning at all. For if the land is far away and the work is urgent, most of the family sleep in the fields until the rush season is over.

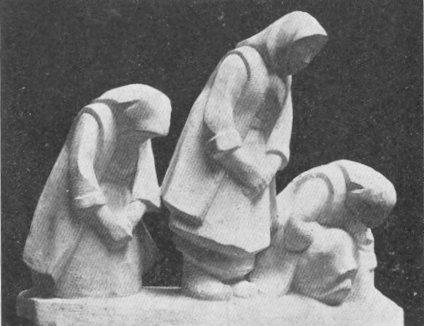

The Bulgarian women, massive in spirit, bear massive

burdens

Statue by Ivan Lazaroff

In this imperious, irresistible drive, individual units disappear. Personal caprice and inclinations are set aside. The entire village family turns itself into a machine and with flawless precision carries out irrevocable commands. And who gives the commands? It is the "chorbadjia". That is, he delivers them. They really come from the land and sun and winds and rain. They are orders which no alert and selfrespecting tiller of the soil could fail to hear but it is through the "chorbadjia" that they are expressed. And who is he? Literally the word means "the man of the meat stew". In ancient times the villagers in this part of the world who were rich enough to eat meat must have been marked persons. Meat eating must have been the privilege of a favored few, of the first men in each community. So today a meat eater or "chorbadjia" is the big chief, the boss. Every village has its "chorbadjia" or "chorbadjias" as well as every store, workshop and peasant family. In the family he. is usually the grandfather or oldest brother. And this chief is still absolute master of the household. The group he rules is not so large as it used to be, for now married sons frequently leave and create independent establishments but still in each group there is a supreme master or "chorbadjia". He controls the purse, buys and sells, daily gives every member of the household his task; sending one out with the sheep, another to market, a third to the vineyard and the rest to the fields. He determines who may go to school and where, says who may marry whom and when, where corn is to be planted and where wheat, whether or not the younger generation may discard their moccasins and replace them with shoes and whether to permit that acme of frivolity, a store shirtwaist; but it would be utterly useless for the women to speak to him of bobbed hair and a city hat. He and the other "chorbadjias" gather occasionally in the village saloon and decide which land shall lie fallow, which will be sown to forage and what areas are to be irrigated, for in a village they all act together. If one peasant planted corn in the fallow district or wheat among the corn fields all the crop he would get would be quarrels with his neighbors and their sheep.

These "chorbadjias" keep the church in order and their "pope" too, impress upon the teacher the seriousness of his task, occupy the official communal offices and pass judgment on the economic and moral worth of every body in the place. They together with their wives or "babas" — any woman above forty is a "baba", which means grandma — preserve the customs and traditions of the community and race. They are a stern and rigid lot. They walk in the ways of their fathers and make every body walk in theirs. They tend to dislike innovations and suspect reforms. They were all raised in the school of bitter experience and have become hard and unyielding. They are the fittest, who have survived, and they impose their will.

It is they who preserved the Bulgarian nation. Although illiterate and persecuted by Turks and Greeks they were too obdurate and stubborn to adopt foreign vogues. They were too set in their ways to resent being ridiculed by more cultured peoples. They were too obstinate in their devotion to rustic habits and a peasant "jargon" to accept modern customs and speech and by that they preserved Bulgarianism for centuries against overwhelming foreign encroachment. You may picture the Bulgarians as a faithful flock being led through long, hard ages by stern, thin faced, beardless, long mustached "chorbadjias", with black "kalpaks" on their heads, with tiny bands of wool along the collars of their coats to denote authority, with unspeakably ugly pants, huge seated and tight legged and with low coarse black shoes on their feet. These grandpas are silent and the only sound they make is the clicking of the beads in their hands, yet with their grim visages they eloquently say "Let the world do as it pleases, but as for us and our families we'll follow the gods of Bulgaria" and they have.

Life in a village home centers about the fireplace

They, of course, made a narrow, hard, pioneer world. They were both despots and insurgents. They cared little for the state, for the larger authority, for the supreme "chorbadjia", who was almost always a foreigner. They gave as little to Caesar as they could and grudged that little. The village was their unit and to it they accorded their loyalty. There they were not insurgents but preservers of order. There they did not defy authority but exercised it.

They were both absolutistic and democratic. Absolutistic because the "chorbadjia" demanded obedience. When he entered the humble house every body arose. No one started to eat at the simple table on the floor until he did. He controlled the money and time of his grown sons; demanded utter obedience from his wife and daughters-in-law. Yet in a way he exercised only delegated authority. He was one of the group he ruled. He worked with them as hard as the humblest. He had won his position. He was on the same social level with all the others. There was no grand lord or titled master above any of them. And the land he managed was the family land. It was inherited equally by all. The money he held was for the benefit of all. There was a crude and terrible justice which no "chorbadjia" dared defy. He ruled his family and his family ruled him. Such was village authority.

There are over 5,000 villages in Bulgaria today and only one town with

100,000 inhabitants. It is still the villages that give tone and direction

to the spiritual life of most of the nation. They make character narrow,

hard, stern, honorable. They produce virile, unyielding personalities who

still try to move straight ahead in spite of the bewildering cross roads

of modern life.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]