VI. PEASANTS, CRAFTSMEN, MERCHANTS AND WARRIORS

1. Peasants 151

3. Warriors 166

The basic importance of agricultural production in the life of the Slavs is documented, among other things, by the Czech legend of Přemysl the Ploughman, the founder of the first local dynasty. The mural paintings in the rotunda at Znojmo depict the scene when Přemysl was summoned to the court while he was ploughing (twelfth century).

The historical development of the ancient Slavs, which we have been trying to outline, was based on their economic life, agricultural and crafts production and the barter that it involved. Historic sources provide only sparse information in regard to the earliest period. Here archeology comes to our aid with its finds of work tools, production tools and the resulting products, workshops and other premises, and evidence of trade. This is true even for such an integral part of life as military involvement, whose level determined possibilities of expansion and the settlement of new territories, internal social development and even the first political organization. We shall now try to take a look at these aspects in the life of the Slavs in the early Middle Ages.

1. PEASANTS

Finds of carbonized remains of plants in the Slav villages from the sixth and seventh centuries (e.g. at Březno near Louny in Bohemia) show that their inhabitants cultivated cereals: wheat, rye, barley, oats and millet. But they also grew pulses such as peas and lentils as well as plants like hemp whose fibre was used in craft work. As far as fruit trees are concerned there have been finds only of plum tree wood, and there are no traces of vegetable growing.

The cultivation of a large number of different crops suggests a relatively advanced agriculture, in which crops requiring fertile soil alternated with less demanding types. This corresponds to the manner of working the soil in which part of the fields were left to lie fallow for more than a year.

What was especially important was the discovery that the Slav settlers brought along with them to their new homes — a species of wheat which gave higher yields. From the sixth century on this replaced the more primitive wild einkorn and wild emmer, which were widespread in Central Europe before their arrival. This shows that the economic level of the earliest Slavs was by no means low; on the contrary, it shows that they were good farmers who raised agricultural production in the newly occupied lands to a higher level.

The finds of the better wheat and bones of oxen are proofs that the land was tilled and the ox used as a draught animal. The soil was manured by grazing cattle on the fallow fields and with ashes from the burnt stubble. The fallow fields were also burnt off from time to time. Otherwise burning was used when new villages were laid out and new ground opened up for cultivation.

Since, after a certain time, the soil around the village became exhausted, villages were temporarily abandoned. A similar, mostly locally limited shifting of villages, or possible return to the original sites can be observed in Slav settlements of the sixth century in Poland and the Ukraine, and this phenomenon is even recorded in Byzantine reports for this period (for example, by Procopius of Caesareia). In view of the advanced level of agricultural production this form of agriculture cannot be considered nomad.

A very important aspect of the economy of the early Slavs was cattle breeding. Without large herds of cattle, which provided food and served as beasts of burden for transporting supplies and the modest amount of property, the long journeys of the Slav tribes at the time of the migration of nations would not have been possible. Cattle breeding, however, was not the main but a subsidiary way of making a living — in this the Slavs differed from the typically nomad tribes such as the Huns, Avars or the ancient Magyars.

According to finds of bones they kept mainly beef cattle (Bos primigenius f. taurus L.), relatively small in size with short curved horns. Then pigs, but it is not certain to what extent they hunted wild pigs, from which the domestic animals do not greatly differ in appearance. Sheep and goats held third place together, it being difficult to distinguish the bones of one from the other. Then followed domestic or wild poultry, and the rest comprised the horse, dog, and hunted animals. In the case of domestic animals, they were hardy beasts that ran free around the village and did not require roofed stables or pens, which were a later feature.

In the early Middle Ages advances were made in farming methods not always on the same level. In the eighth and ninth centuries there was a substantial improvement in agricultural techniques and a certain intensification of production, as shown by the larger

151

![]()

quantity of tools found and a dense network of permanent settlements that were no longer shifted. This development is in accordance with social changes, which led to the establishment of the first Slav states in the ninth century.

The overall statistics of finds of grain from the time show that an important role was played by millet, roughly equal to wheat, followed by rye, oats, barley, peas, vetches and hemp. Cultivation of flax is proved only indirectly in finds of textiles.

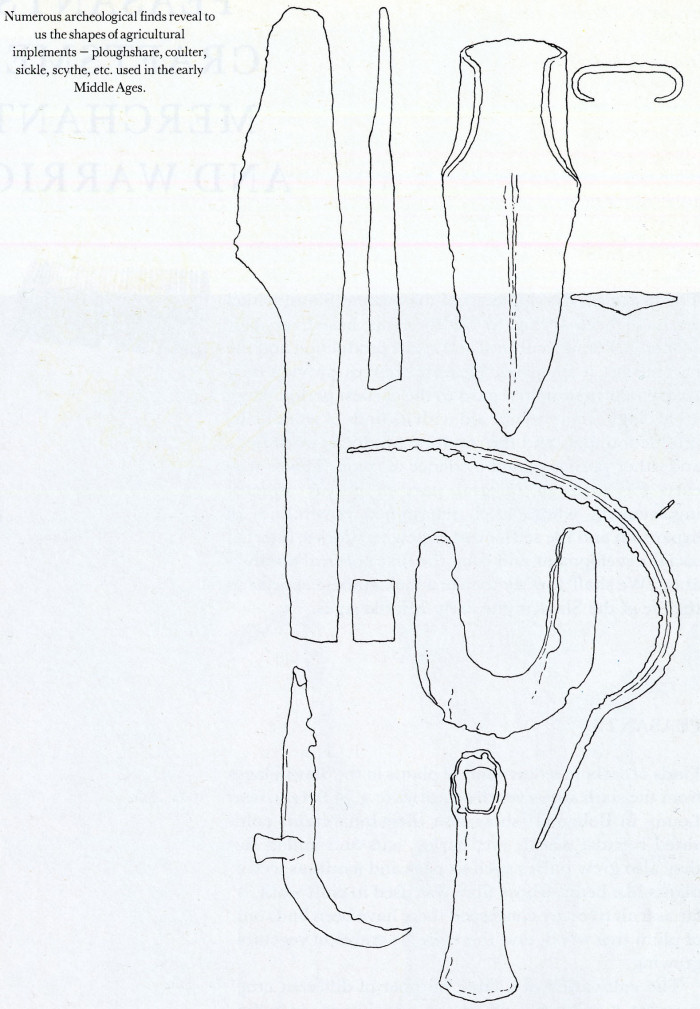

Numerous archeological finds reveal to us the shapes of agricultural implements — ploughshare, coulter, sickle, scythe, etc. used in the early Middle Ages.

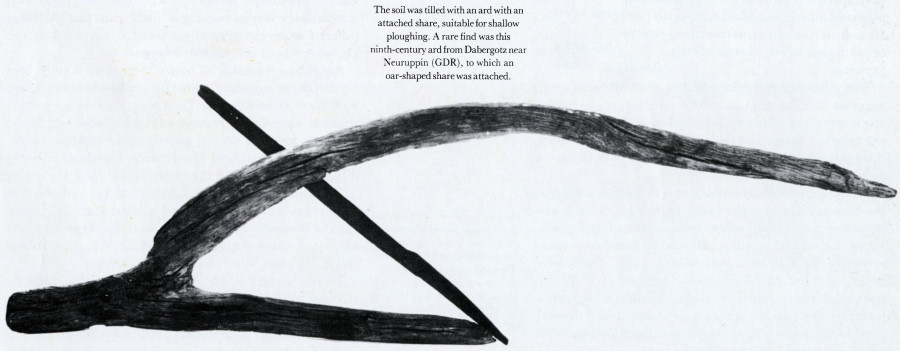

The soil was tilled with an ard with an attached share, suitable for shallow ploughing. A rare find was this ninth-century ard from Dabergotz near Neuruppin (GDR), to which an oar-shaped share was attached.

We can learn about the shapes of agricultural tools from several large-scale finds — probably forgotten stores of merchants or peasants in difficult times, as well as finds of individual objects in the villages. These make it clear that ards were used primarily for tillage, equipped with small iron shares, suitable only for shallow turning of the sods. Larger shares that could be used for deeper tillage were very much the exception. Some ards had coulters, which cut apart the soil in front and made it possible to open it up from underneath. They even used sole ards with long oar-shaped shares made of iron or wood. This was shown by a rare find at Dabergotz near Neuruppin in the German Democratic Republic, dated, with the aid of radio-carbon tests, to the eighth century. More rarely ploughs were used for tillage even though their existence has been proved during the eighth century. This is confirmed by finds of asymmetrical plough-shares which together with a mouldboard and coulter served to cut the furrow from underneath and turn it over. In the shallow tillage there was no great need to turn over the soil and therefore the plough was not widely used in the early Middle Ages. A change occurred only in the thirteenth century when, together with the general changes in farming methods, tillage using large and heavy ploughs began to be

152

![]()

introduced. From that time on we have proof of the use of harrowing with iron harrows.

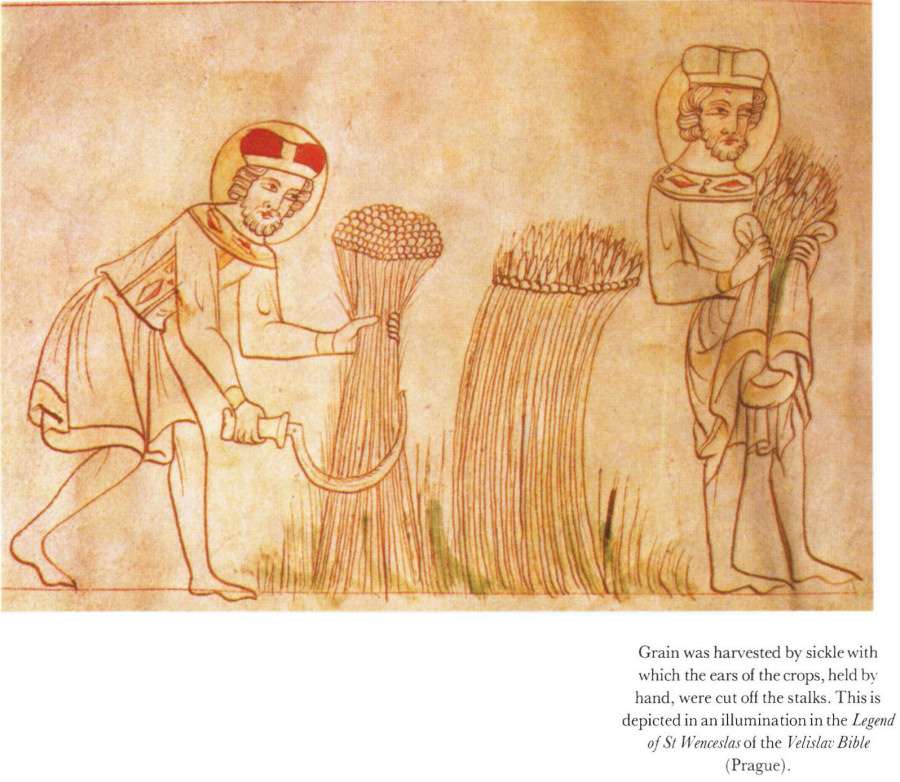

At harvest time the early Slavs did not use scythes but sickles with which they cut only the ears held in the hand. It was hard work but only a relatively small amount of grain was lost. Straw remained on the fields, where it was either burnt or ploughed under. From the thirteenth century on they began to use the straw to make manure, and so the corn was cut lower to the ground with longer sickles, adapted in shape for the purpose. The scythe was known in the eighth century, but it was only used for cutting grass.

Grain was harvested by sickle with which the ears of the crops, held by hand, were cut off the stalks. This is depicted in an illumination in the Legend of St Wenceslas of the Velislav Bible (Prague).

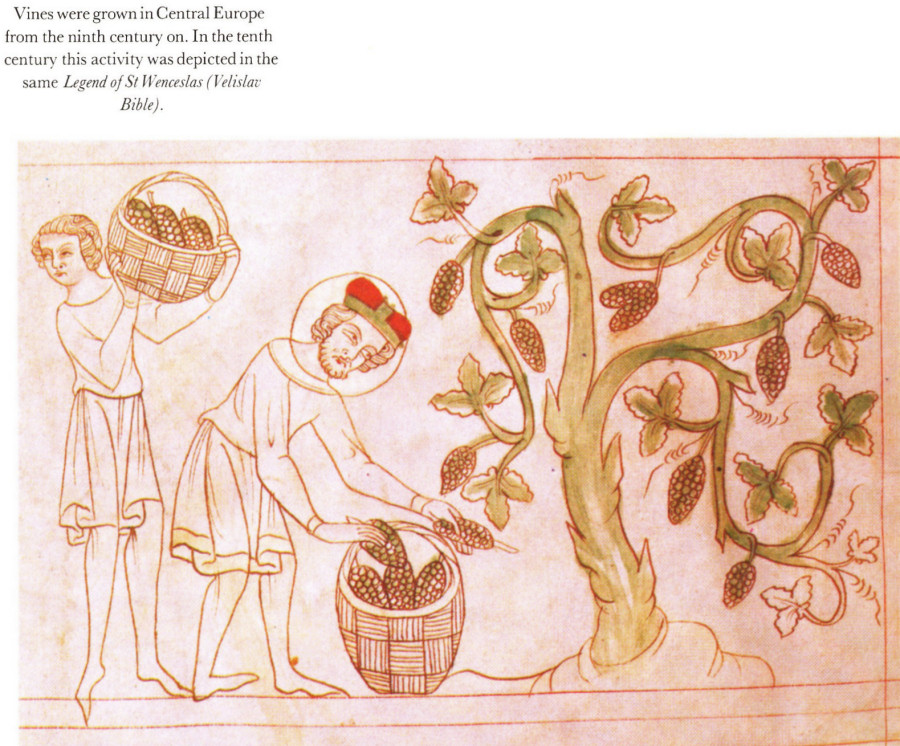

Vines were grown in Central Europe from the ninth century on. In the tenth century this activity was depicted in the same Legend of St Wenceslas (Velislav Bible).

The corn was threshed with flails, husking was done on wooden crushers by hand or foot, and the grain was stored in pits. These were two to three metres (six to ten feet) deep, usually pear-shaped or in the form of a pouch with a narrow neck and the walls were burnt dry and lined with straw. Once the corn had been poured in, the opening was closed tightly, covered over with clay and protected by a little roof. This method of storage, providing conditions that were airtight and at an even temperature, had the advantage of protecting the grain from pests, and automatically conserved the grain and did not impair its germinative power. For those reasons it survived in many regions until the nineteenth century. In places the home grinding of corn on millstones turned by hand, survived into the modern era in the exact way it was already known from the early Middle Ages on. Only in the eleventh and twelfth centuries with the onset of feudalism were watermills and windmills increasingly used.

The pulses they cultivated included peas, lentils and beans. Cucumbers were grown as early as in the ninth century, other kinds of vegetable only being referred to in later records.

Even fruit was cultivated: we know of most kinds of fruit only from medieval finds or reports, but peach- and plum-stones as well as walnuts were found in ninth-century strata. At that same time the Slavs were already growing vines in some areas, e.g. in Moravia, though rather crude varieties. Improvements took place only in the late Middle Ages. Hops to make beer were only gathered to begin with, but from the thirteenth century on they were actually cultivated. The Slavs' favourite drink — mead — points to bee-keeping, but there is no archeological evidence of this.

In livestock production, throughout the early Middle Ages, attention was mainly devoted to the breeding of beef cattle, while pig breeding gradually assumed increasing importance so that in some excavations it predominates. The third place is reserved for sheep and goats, then poultry; geese were relatively rare at the beginning. Duck and pigeon were recorded only in later reports. Apart from the bones of animals kept for food, bones of horses have been found in the villages, which served chiefly for transport and as beasts of burden. After the thirteenth century they were used as draught animals; until that time only oxen had been used for this purpose. There were also bones of dogs, cats and, on isolated occasions, donkeys.

Among the first settlers cattle breeding was extensive for many centuries, which means that the cattle were grazing freely most of the year. Only in winter was fodder provided, as shown by finds of scythes which were used to cut grass. Initially they were short semi-scythes, and from the fourteenth century on they were replaced by today's long-handled scythes. Rakes and forks were likewise found only in the later Middle Ages.

153

![]()

At that time there appeared the horseshoe — in connection with the increasing use of the horse as a draught animal. Finds of hunting arrows and fishhooks suggest the existence of hunting and fishing, which, however, did not play such a great role as the breeding of animals.

Among the early Slavs both crop and livestock production were extensive. That does not mean that they were not profitable — on the very contrary: extensive agricultural production was less exhausting, needed smaller quantities of seeds and did not suffer so much from bad harvests and bad weather. But its disadvantage was that it required large areas. This meant that, as the population grew, it could not continue for long.

Old hunting practices included falconry. This is confirmed on a silver plaque with the motif of a falconer from Staré Město in Moravia (ninth century).

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, therefore, the existing grass and field system of enclosures was replaced — as an innovation of feudalism — by the relatively more intensive "three-field" system where two-thirds of the land was sown alternately with winter and summer crops and one third was left to lie fallow and used for pasture. In this way it was possible to use larger areas of land, which were readily at their disposal, to achieve higher production and fed a larger number of people — but at the cost of far more labour, which involved tillage with a heavy plough, more exhausting harvest work, manuring and harrowing the fields. For the country people this technical improvement meant a worsening of living conditions and feudal serfdom. But such was the fate of the whole of Europe at the time.

154

![]()

2. CRAFTS AND TRADE

The first Slav settlers made all their own things — tools, crockery, clothing, footwear and weapons — or they acquired them through barter or as loot. As soon, however, as the newly occupied lands were consolidated and agricultural production began to increase, there was a greater need for better adapted tools, and substantial changes occurred. By degrees division of labour evolved as a prerequisite of the new stage of economic and social development. People began to specialize in individual crafts and this made trade possible, led to the origin of town centres and the social stratification of the population.

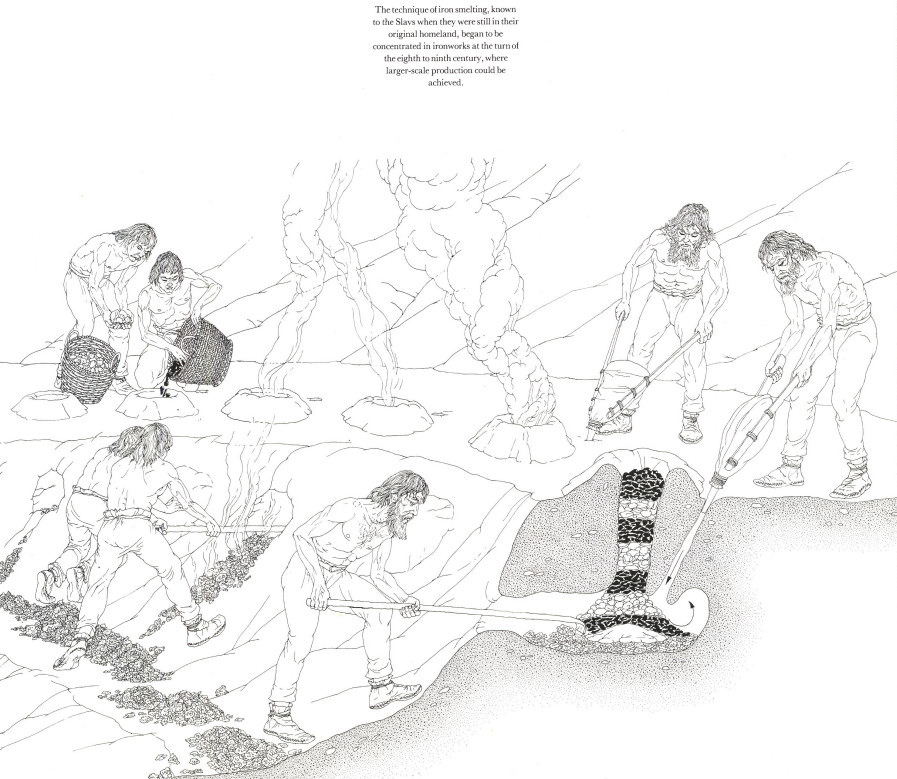

The technique of iron smelting, known to the Slavs when they were still in their original homeland, began to be concentrated in ironworks at the turn of the eighth to ninth century, where larger-scale production could be achieved.

The first to become specialized were the iron smelters and blacksmiths, who prepared and utilized the basic raw material for the production of working tools and weapons — iron. The technology of iron smelting spread to Europe from Asia Minor in the first millennium B.C. and was already known to the Slavs when they were in their original homeland beyond the Carpathians. At the turn of the eighth to ninth century this production began to be concentrated in iron forges, which ensured production on a larger scale. At Želechovice in Moravia twenty-four smelting ovens were discovered from that period, and similar finds have been made elsewhere. As the analysis of iron objects has shown, the Slavs had mastered the production of steel by the ninth century.

155

![]()

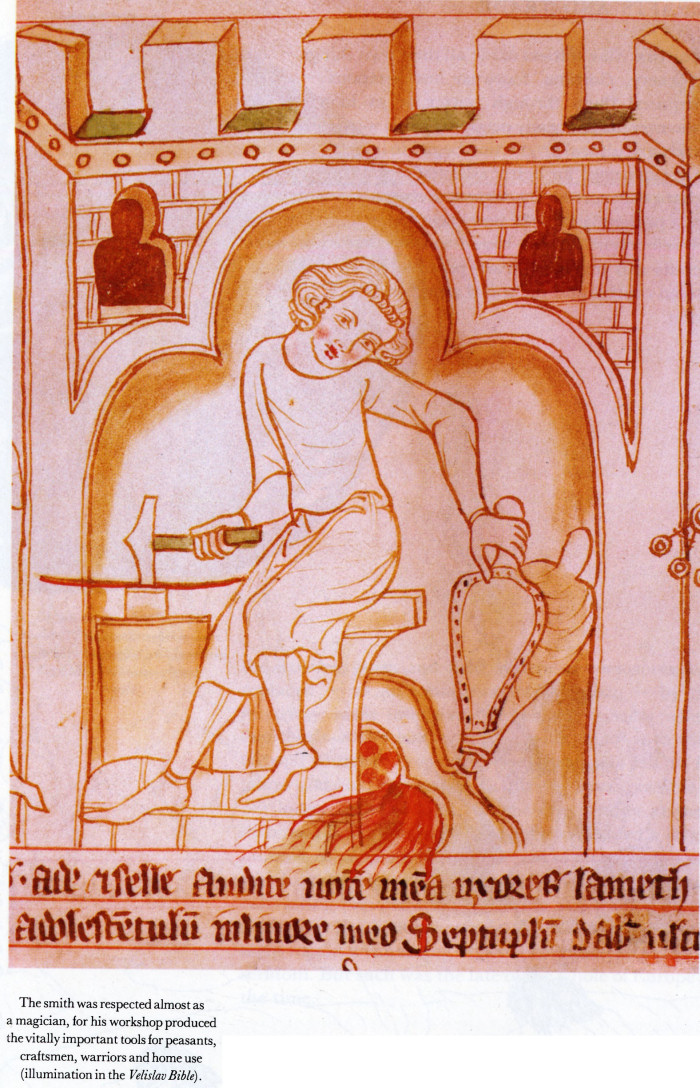

The smelted iron was material for the use of the blacksmith, whose work was of fundamental importance to the community of the time and was highly rated. The smith worked with fire and used the hard iron to create tools that were virtually indispensable, and he was, therefore, respected almost as a magician — this can be seen in the numerous motifs in legends and fairy-stories. His forge produced mainly tools to work the land, instruments for craftsmen, articles needed in the home and in particular the essential outfit and equipment of warriors.

The smith was respected almost as a magician, for his workshop produced the vitally important tools for peasants, craftsmen, warriors and home use (illumination in the Velislav Bible)

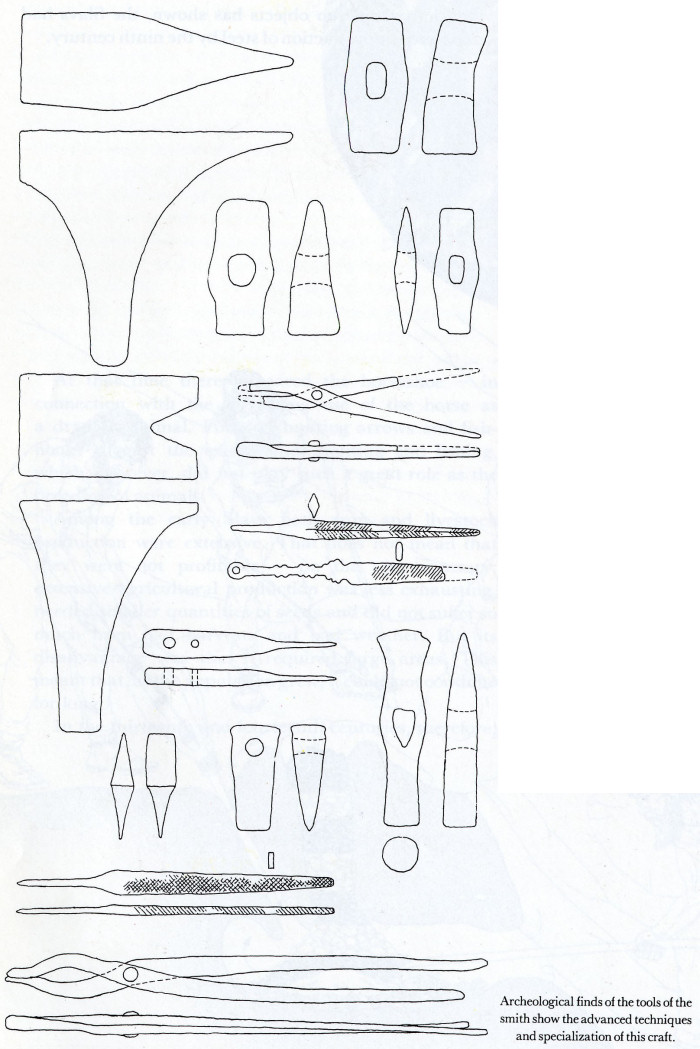

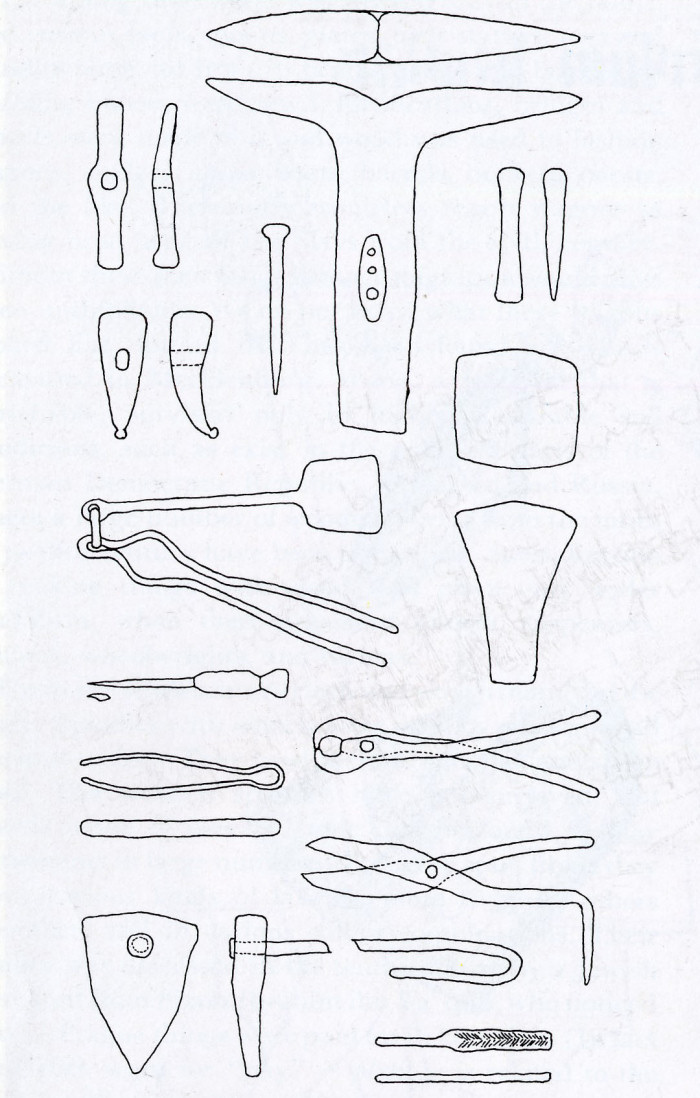

Archeological finds of the tools of the smith show the advanced techniques and specialization of this craft.

Metallographic analysis has revealed the techniques used by the smiths. It was found, for instance, that the smith was already able in the ninth century to attach

156

![]()

steel edges to the iron blades of swords and daggers. They were also acquainted with the technology of Damascus blades, otherwise known only in the Orient and in the Rhineland. The location of forges inside and outside the hill-forts is indicated by finds of hearths, anvils, tongs, half-finished items and waste. In the tenth to eleventh centuries whole hamlets came into being, of which the inhabitants were specialized in blacksmiths' work and paid their tithes to the prince in the form of products, i. e. they were service villages. Similar villages existed also for other crafts.

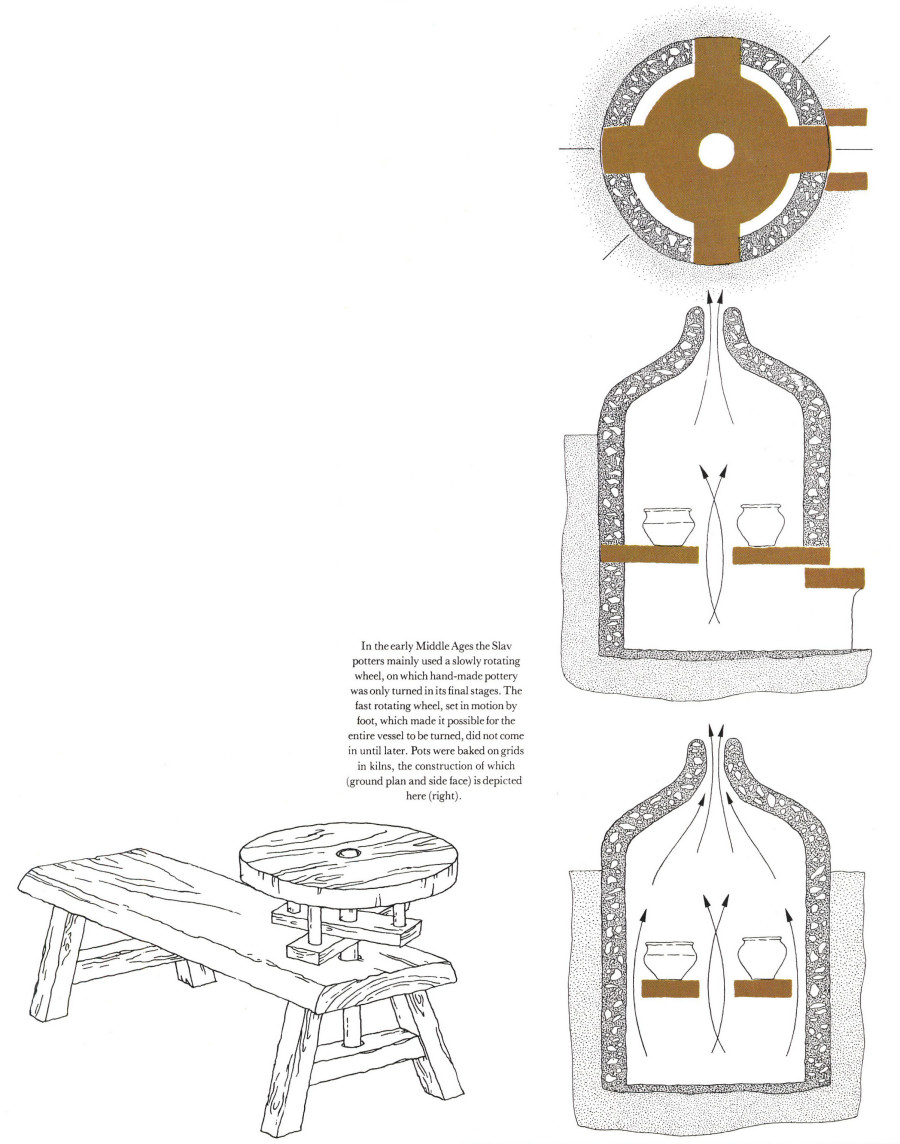

In the early Middle Ages the Slav potters mainly used a slowly rotating wheel, on which hand-made pottery was only turned in its final stages. The fast rotating wheel, set in motion by foot, which made it possible for the entire vessel to be turned, did not come in until later. Pots were baked on grids in kilns, the construction of which (ground plan and side face) is depicted here (right).

By the side of the iron smelters and blacksmiths there soon appeared the potter. His craft is the oldest extant, for the production of pots was known from the Neolithic Age on. For a long time it was practised in each family and was considered the work of women. Pottery as a craft eventually appeared in the more advanced cultures of antiquity. But among the barbarian nations of Europe the potter only appeared with the transitory feudalism. This was the case among the Slavs. Large-scale production began only in the ninth and tenth centuries; it was carried out by specialized craftsmen and depended on technical improvements. From the free shaping of a pot by hand they went on to turning it on a wheel moved by hand and finally to turning pots on a rapidly turning wheel set in motion by foot. The finished products were then baked on grates in clay kilns, whole batteries of which were located in the vicinity of the main centres. The work of the potter was also reckoned to contained a bit of magic — hence the various symbols on the bottom of the pots (cross, cross in a circle, swastikas, wheels, pentagrams, hands, etc.), which, after the transition to craft production, became potters' marks. The potter produced not only pots, dishes, and bottles, but also whorls, little figures, toys, and cult objects, among them painted eggs (pisanki) which spread from Kievan Russia in the ninth century.

157

![]()

For a long time wood was worked only in the home, and various tools, spoons, plates, little statues, toys and handles were cut from it; beams, posts and boards for building houses were hewn; fortifications, bridges and wheels were made of it and wood was used to fashion wagons, sledges, ships, boats, barrels, buckets, chests, and the like. Byzantine chroniclers report wagons as having been used by the Slavs from the sixth century. Without these their long-distance migration would have been unthinkable. We do not know what these wagons looked like, for all that has been found are wheels excavated in Mecklenburg. Wood, a material that is perishable, survived only in highly favourable soil conditions, such as exist in the northern parts of the German Democratic Republic, in Poland and Russia, where a large number of wooden objects from the ninth to twelfth century have been unearthed. Specialization in making things with wood took place only under feudalism, when there appeared joiners, carpenters, coopers, wheelwrights, and turners.

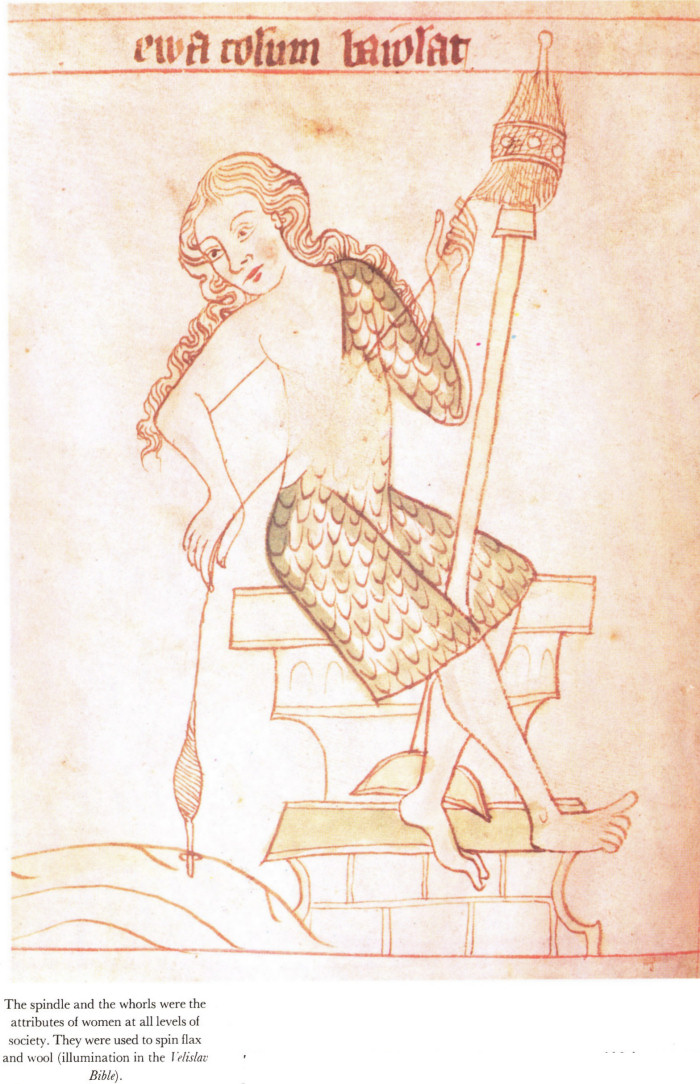

Up to the tenth century cloth was woven mainly in the home. Spindles with whorls were used by women at all levels of society. They used them to spin flax and sheep wool. The wooden spindles have not survived, but whorls made of clay or stone can be found in Slav settlements in large numbers. From the spun fibres they wove various kinds of fabrics, some rougher, others smoother, and in various colour combinations. Their quality was discussed in the tenth century by a Jewish merchant from Spain Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb, who noticed that in Prague things were paid for in kerchiefs. (In fact the Czech word for "pay" — platit — is related to the word for "linen cloth" — plátno.)

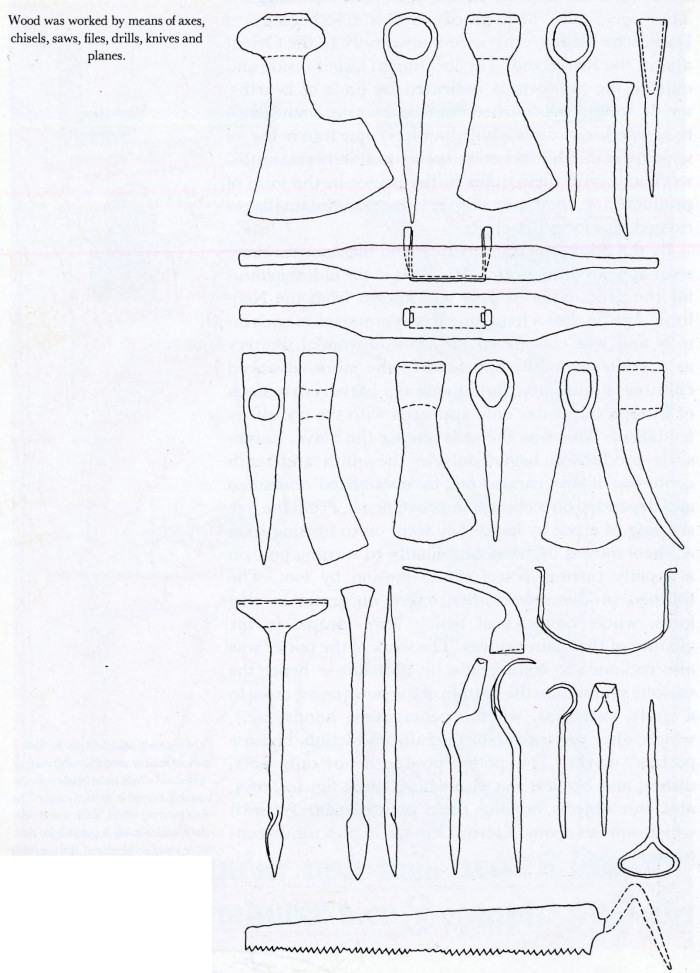

Wood was worked by means of axes, chisels, saws, files, drills, knives and planes.

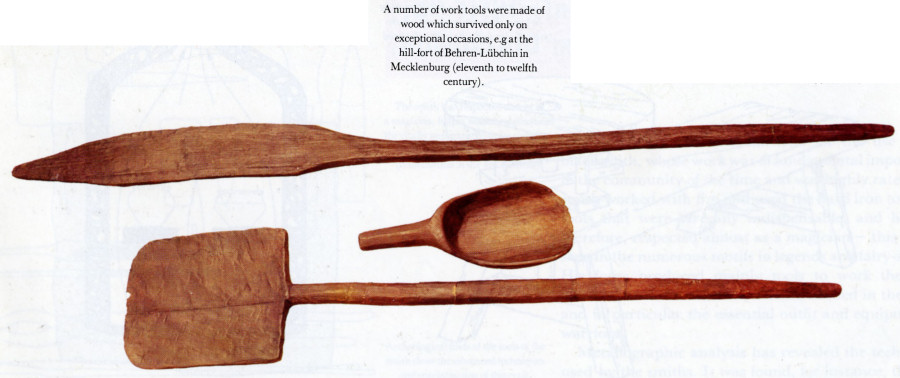

A number of work tools were made of wood which survived only on exceptional occasions, e.g. at the hill-fort of Behren-Lübchin in Mecklenburg (eleventh to twelfth century).

The narrow strip of material was woven with doffer combs or plates, broader material on a weaver's loom. Originally it was a vertically placed frame with clay weights, which, in the ninth and tenth centuries, was replaced by a horizontal loom which probably spread to Central Europe from Byzantium via the Balkans. With the improved loom there arose the independent craft of

158

![]()

the weaver. But clothes continued to be sewn by women, even among the nobility, as shown by the find of a golden needle in the tomb of a Slav princess at Alt Lübeck.

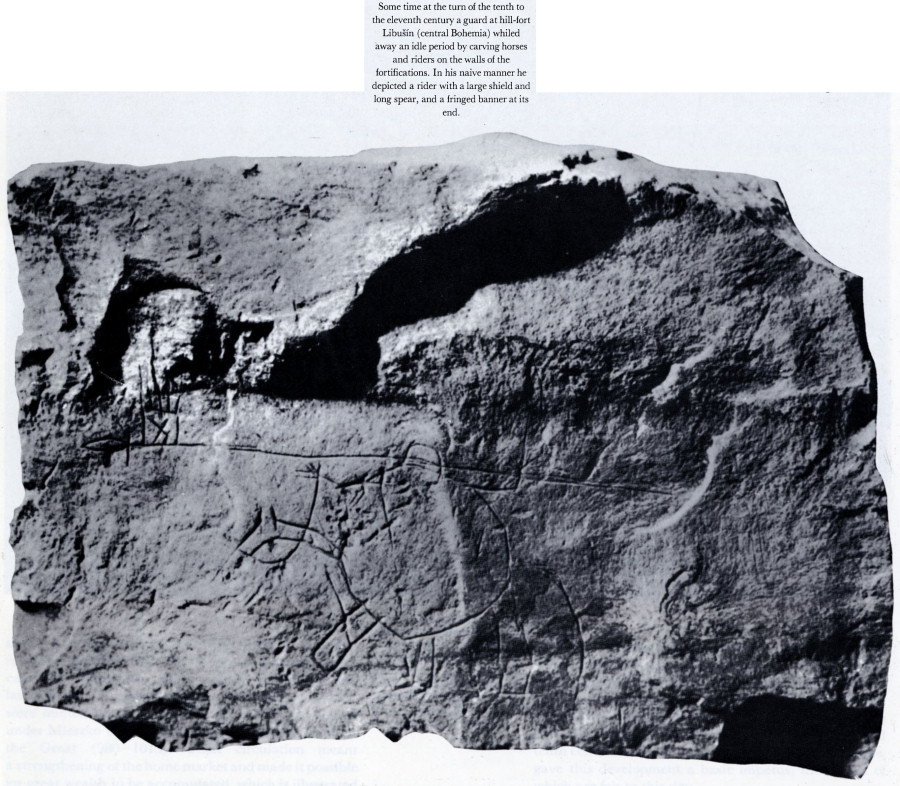

Tanned animal skins were made into boots, fur coats, caps, and gloves and they were also used for shields, saddles, quivers and sheaths. The work of tanning has been proved on Slav sites by finds of pits with marks of lime and remnants of skins. Tanning as a craft came into being under feudalism, as did the production of footwear, which can be shown by finds of carefully shaped, sewn footwear decorated with hem-stitching at Polish Wolin, Opole, Gdańsk, and elsewhere. Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb speaks of the production of saddles and shields in Prague. The products have not survived but the form of the shields is known from pictures on stone walls at Libušin, dating from the turn of the tenth to the eleventh century, from the Vyšehrad Codex (end of the eleventh century) and mural paintings at Znojmo in southern Moravia.

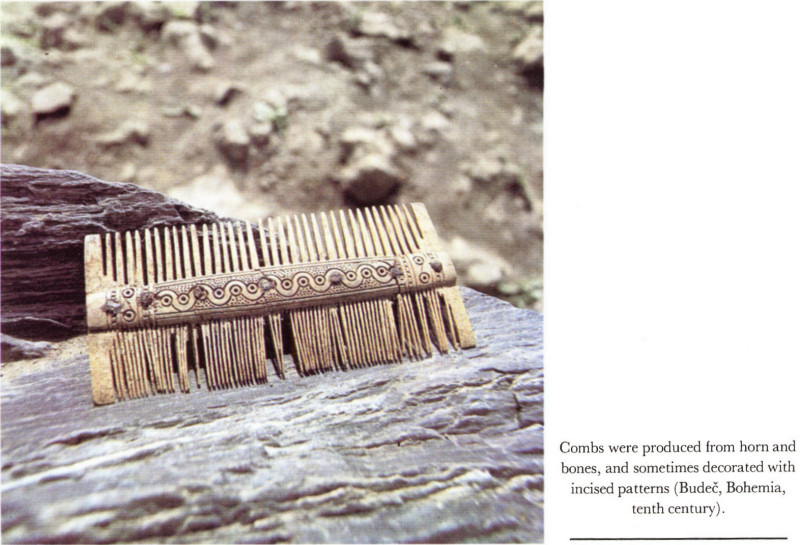

Work involving horn and bone was also of a high standard; it was used to fashion combs, handles, ornaments, dice, pipes, needles, awls and "skates". Many of these objects were richly adorned with engraved patterns. An example is a comb from the residence of the Czech princes at Budeč, the product of the local tenth-century workshop.

The spindle and the whorls were the attributes of women at all levels of society. They were used to spin flax and wool (illumination in the Velislav Bible).

Combs were produced from horn and bones, and sometimes decorated with incised patterns (Budeč, Bohemia, tenth century).

The uncrowned king of craftsmen — even if his status was usually that of slave or serf — was, undoubtedly, the goldsmith and jeweller, whose products belong to the sphere of the arts and crafts and are a sensitive barometer of the cultural level of their time and setting. In the Slav countries this craft flourished in the ninth and tenth centuries; the beginnings, however, date back to the seventh and eighth centuries. They worked both less precious metals — copper and pewter, from which they cast bronze — and silver and gold, by casting them into stone or wax moulds and by hammering, plating, engraving, punching, granulating, filigreing and latticing with enamel. This gave rise to the multi-coloured, highly original magnificence of the jewels of the Great

159

![]()

Moravian Empire, Croatia, Bulgaria, Bohemia, Poland and Russia, so much admired to this day.

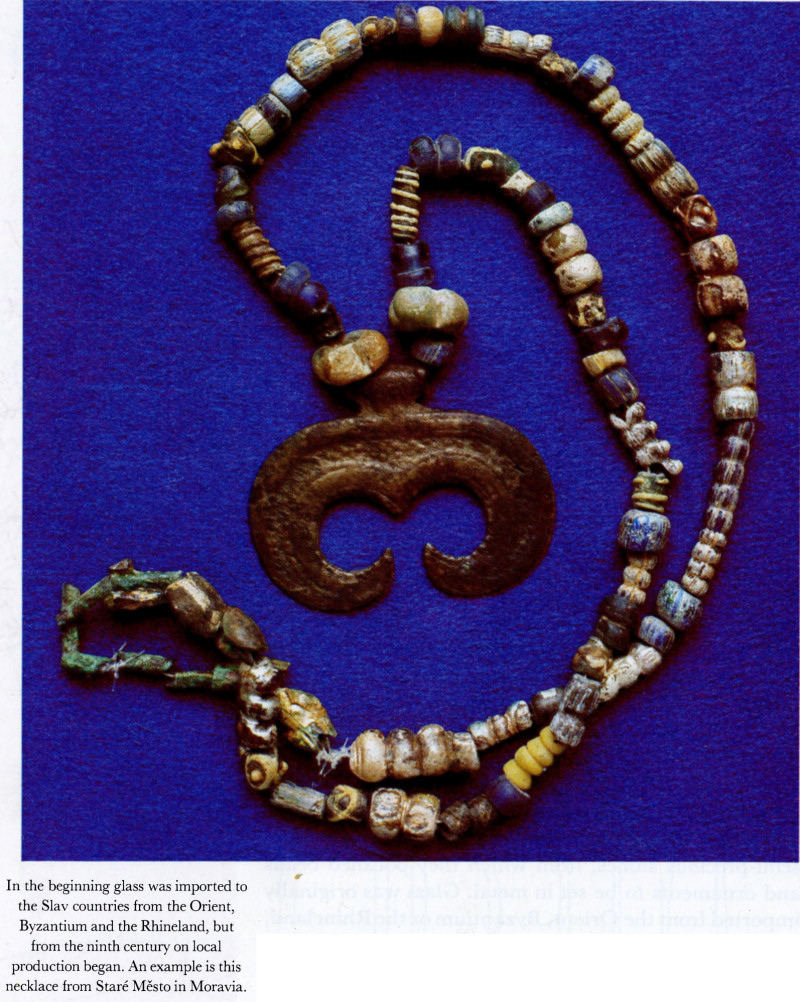

In the beginning glass was imported to the Slav countries from the Orient, Byzantium and the Rhineland, but from the ninth century on local production began. An example is this necklace from Staré Město in Moravia.

The art of the Slav jewellers flourished first in the ninth and tenth centuries. This is confirmed not only by the items themselves, but also by finds of specialized tools.

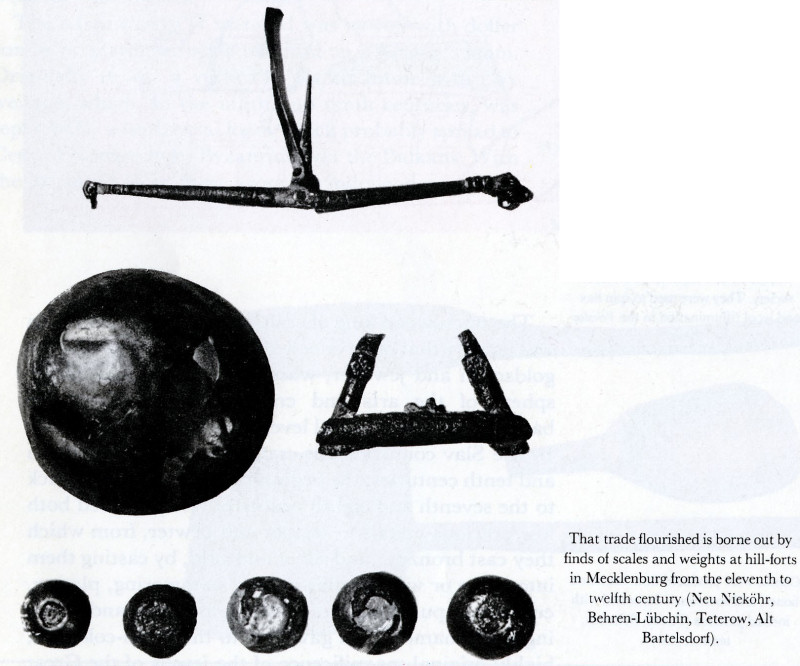

That trade flourished is borne out by finds of scales and weights at hill-forts in Mecklenburg from the eleventh to twelfth century (Neu Nieköhr, Behren-Lübchin, Teterow, Alt Bartelsdorf).

The craft of the stonemason likewise did not develop until the feudal period, when it arose in connection with the building of cathedrals and palaces. Prior to that, stones had been hewn only as millstones, whorls, grindstones, moulds for casting metal objects and as building material for fortifications. They also worked semi-precious stones, from which they polished beads and ornaments to be set in metal. Glass was originally imported from the Orient, Byzantium or the Rhineland, but from the ninth century on the Slavs were capable of making it themselves.

As craft production advanced, trade began to develop. It started at the time of Samo, but until the early ninth century trade relations between the Slav lands and the surrounding world were only sporadic. In the ninth century a change occurred. It was related to the growth of production, and the establishment of Slav states and trade centres in Northern and Eastern Europe, which mediated long-distance trade with Byzantium and the Orient.

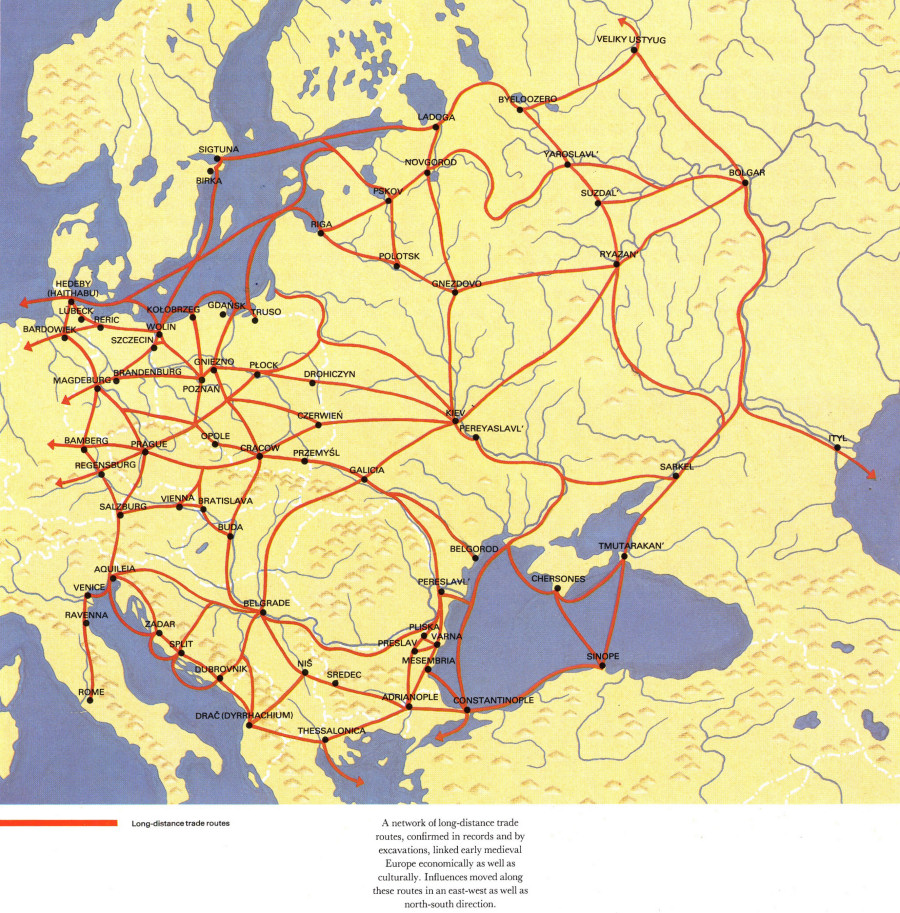

Some of these long-distance routes were known already in the Roman period, for example those along the Danube and the Amber Route, leading from the Baltic through Moravia to the Mediterranean region. Others assumed importance in the ninth and tenth centuries, for example the north-south route that linked Scandinavia via Kiev with Byzantium; the Volga Route, which provided contact with the world of Islam; and, the West-East Route, which led from Kiev via Cracow to Prague and further to the West. In the tenth century Prague was a junction of European routes.

Before the introduction of coinage, talents (of iron or silver)

160

![]()

161

![]()

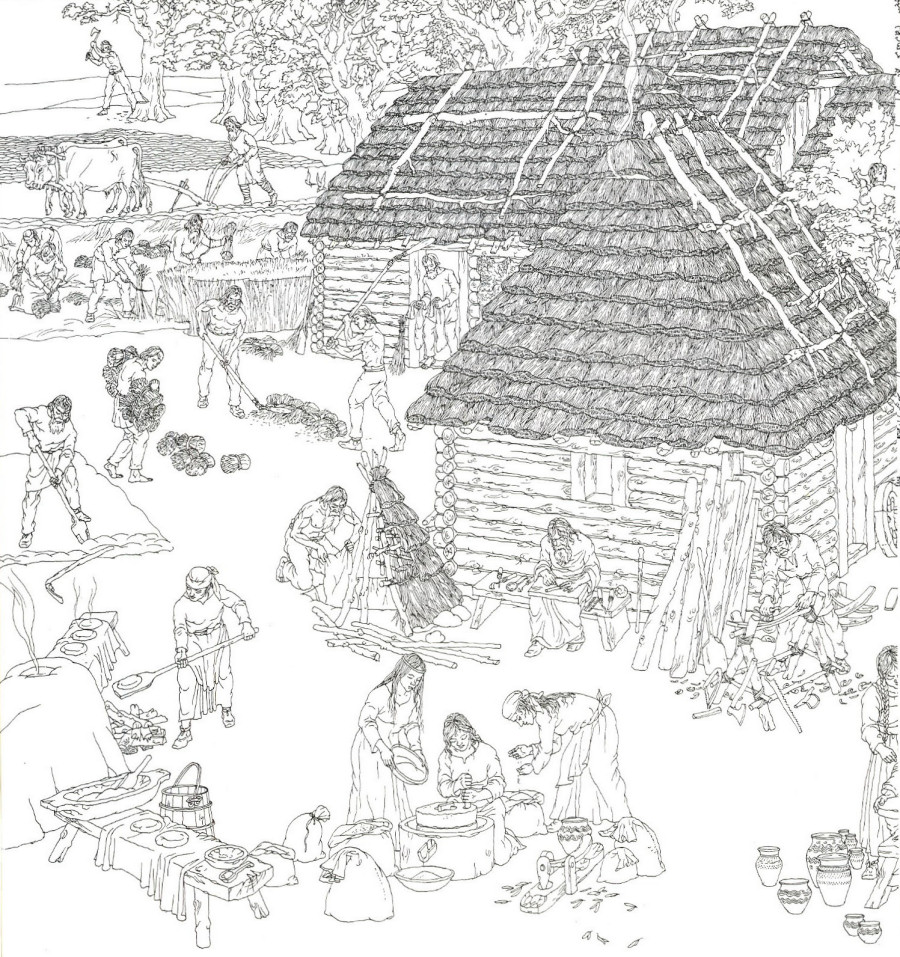

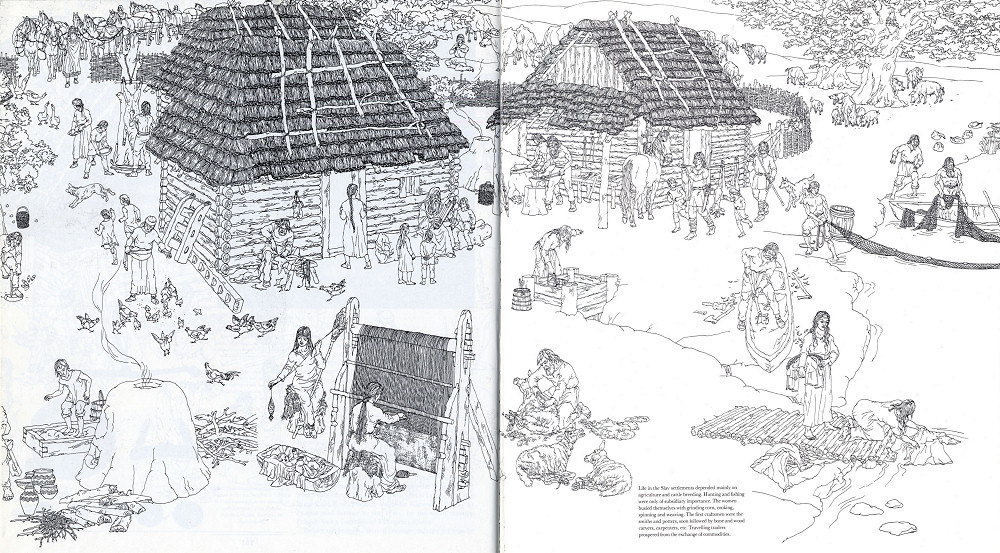

Life in the Slav settlements depended mainly on agriculture and cattle breeding. Hunting and fishing were only of subsidiary importance. The women busied themselves with grinding corn, cooking, spinning and weaving. The first craftsmen were the smiths and potters, soon followed by bone and wood carvers, carpenters, etc. Travelling traders prospered from the exchange of commodities.

162-163

![]()

served as currency, as did weighed silver, fabric, furs, salt, and the like. But before long foreign coins came into circulation, mainly Arab, Byzantine, and later Western European. In Bohemia the first local coins were minted under Boleslav I (929—967), in Poland under Mieszko I (960—992), in Russia under Vladimir the Great (980—1015).

From the tenth century on the circulation of coins made it possible for wealth to be accumulated, as illustrated by finds of hoards close to the main centres and routes. Apart from coins they contain fragments of silver ornaments which served as currency or raw material (the treasure of Schwaan, GDR).

Their circulation meant a strengthening of the home market and made it possible for great wealth to be accumulated, which is illustrated by finds of treasures close to the main towns and routes. Thus, from the tenth century on, a merchant class emerged in the Slav countries to become an important element in society which helped determine economic and cultural development. Specialization of production and in the distribution of products, in the ninth and tenth centuries, connected with the growth of the towns, gave this development a basic impetus, the results of which are felt to this day.

164

![]()

A network of long-distance trade routes, confirmed in records and by excavations, linked early medieval Europe economically as well as culturally. Influences moved along these routes in an east-west as well as north-south direction.

165

![]()

3. WARRIORS

In the period of Romanticism, under the influence of the German philosopher and historian J. G. Herder, the idea was widely accepted of the "dove-like" character of the Slavs as peaceful peasants in contrast to the belligerent Germans. More profound historical and archeological studies, however, have invalidated this idea. Without skill in warfare the extensive Slav expansion in the sixth to eighth centuries would never have taken place, even if it was aided by propitious external conditions. The two great powers of the early Middle Ages — the Byzantine and the Frankish Empires — waged heavy battles against the Slav tribes and states along their borders with varying success over the centuries. The same is true of the constant conflicts between the Eastern Slavs and the nomads from the steppes. The Slav warrior did not basically differ from the German soldier in fitness and skill at fighting. This was expressed clearly by an unbiassed observer in the tenth century, Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb: "Generally speaking, the Slavs are quick to attack and hot-tempered. If there were not so much disunity among them, caused by their being split up into a number of tribes, no other nation could stand up to them."

Some time at the turn of the tenth to the eleventh century a guard at hill-fort Libušín (central Bohemia) whiled away an idle period by carving horses and riders on the walls of the fortifications. In his naive manner he depicted a rider with a large shield and long spear, and a fringed banner at its end.

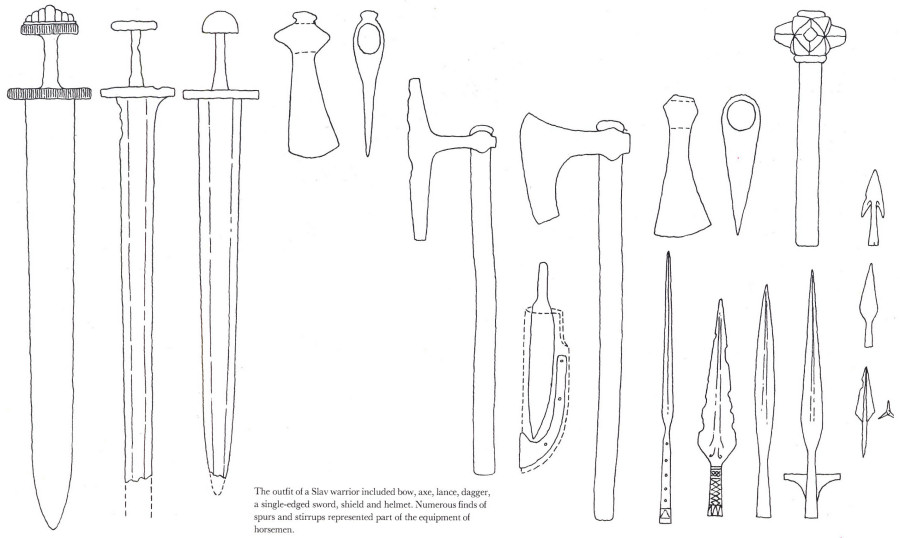

We can learn how the Slav warriors were equipped from finds made by archeologists and from later iconographical depiction. Their main weapon was the bow with arrows that had leaf-shaped iron arrowheads with hooks, or were three-edged or rhomboid in shape adopted from the nomads. Then there was the axe, either light-weight or heavy, with a broad blade, called the "beard-axe". It often had inlaid ornamentation as did the lance, which frequently had pinions. Swords of the early medieval type became highly popular from the ninth century on, despite the prohibition of imports from

166

![]()

the West, mainly from the workshops in the Rhineland. Soon such swords were being produced by local smiths and, like the foreign models, they had decorated hilts. The warriors carried their swords in wooden or leather sheaths sometimes adorned with wrought-metal ornaments. The shields, of inferior quality (as the observant Ibrāhim noticed), were made of wood and leather. In the earlier period they were circular in shape, but from the eleventh century on the predominant type was the Norman shield of oval shape running to a point.

The magnificent stirrup adorned with gilt bronze layers and inlaid with silver probably belonged to a member of the prince's retinue (Zbečno, Bohemia). It came from a Scandinavian workshop and shows that Bohemia had contacts with that area in the tenth century.

The outfit of a Slav warrior included bow, axe, lance, dagger, a single-edged sword, shield and helmet. Numerous finds of spurs and stirrups represented part of the equipment of horsemen.

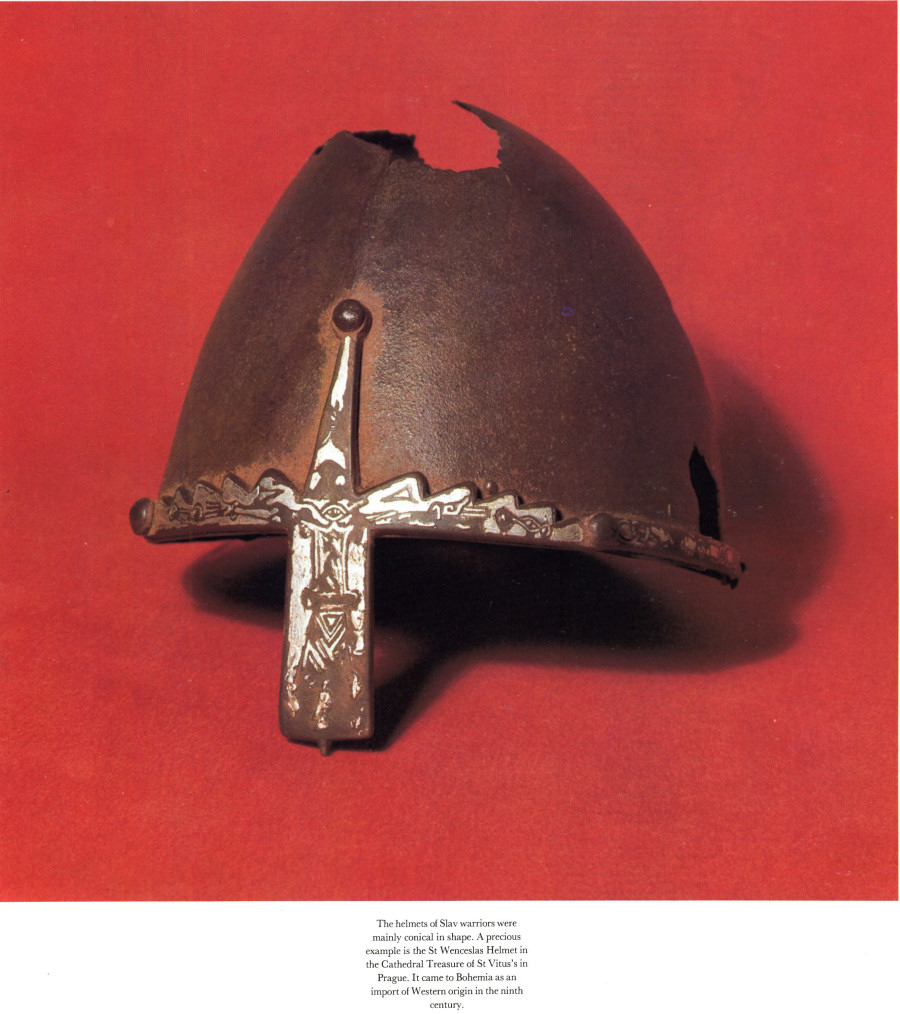

Cavalry formed an important part of the Slav army, even if not as decisive as in the case of the Avars, the Bulgars, Magyars and other nomads. The Slav horsemen differed from these, among others, by wearing spurs. In the sixth to eighth centuries these spurs had hooks at the heel, later loops and, from the ninth century on, there were little side tabs at both ends. They were often highly elaborate with relief decorations and gilding. This was equally true of the rest of the horseman's outfit, in which the straps often had ornamental metal-work. The Slavs probably adopted this custom from the nomads from whom they had learnt to use stirrups. The outfit further comprised cudgels, spiked clubs, scimitars, daggers, and slings. They even wore helmets to begin with of foreign make but soon produced in local workshops. Most of the helmets were conical in shape and in the eastern regions had elongated tops. A beautiful ninth-century example is the St Wenceslas helmet, kept in the Treasure of St Vitus's Cathedral at Prague Castle.

Numerous buildings that served the purposes of warfare provide evidence of the Slavs' skill at fighting and defence: fortifications of hill-forts, castles and even the first towns. Each one was set up at a strategically important location: crossroads of important routes, the confluence of rivers, near fords, on mountain passes or in

167

![]()

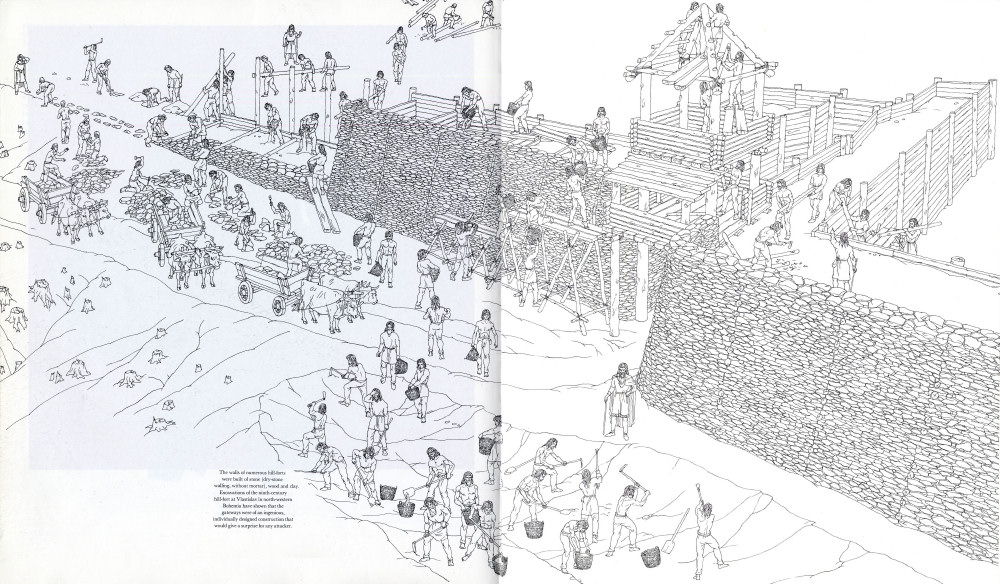

places protected by nature, where inaccessibility was further strengthened by ingeniously located ramparts. In the majority of Slav countries the ramparts were constructed of wood. There was a great variety of different types from simple palisades to complex structures with chambers and soundly secured gratings. The Bulgar regions differed in this respect since even at a very early stage they built stone ramparts in the style of antiquity. In Bohemia and Moravia ramparts were built in the ninth century that were a revival of earlier Celtic fortifications. They had frontal dry-stone walls and broad galleries of wooden construction filled up with clay. This type survived until the twelfth century when stone walls began to be built with mortar. Siege instruments to take castles by storm are mentioned in written sources. The Slavs must have copied these from those of Byzantium, and though their own tools did not attain the perfection of the originals, they were highly effective, for they even enabled the Slavs to penetrate the strong ramparts of Greek towns such as Thessalonica.

In the early Middle Ages to wear armour was a privilege of princes and leading warriors. This magnificent example of a wire shirt and a coat of mail with a collar, is allegedly the property of St Wenceslas (St Vitus's Treasure at Prague Castle).

The abilities of the Slav warriors proved themselves even at sea, especially on the Baltic and Adriatic Seas. On the Baltic they built ships similar to those of the Vikings and often became as accomplished as those feared sailors, even in their skill at warfare, not only in defence of their own shores but also in attacks on the Scandinavian coast.

168

![]()

The helmets of Slav warriors were mainly conical in shape. A precious example is the St Wenceslas Helmet in the Cathedral Treasure of St Vitus's in Prague. It came to Bohemia as an import of Western origin in the ninth century.

169

![]()

The walls of numerous hill-forts were built of stone (dry-stone walling, without mortar), wood and clay. Excavations of the ninth-century hill-fort at Vlastislav in north-western Bohemia have shown that the gateways were of an ingenious, individually designed construction that would give a surprise for any attacker.

170-171

![]()