VIII. THE TRAGEDY OF THE NORTH-WESTERN SLAVS

1. The Lusatian Centre at Tornow 213

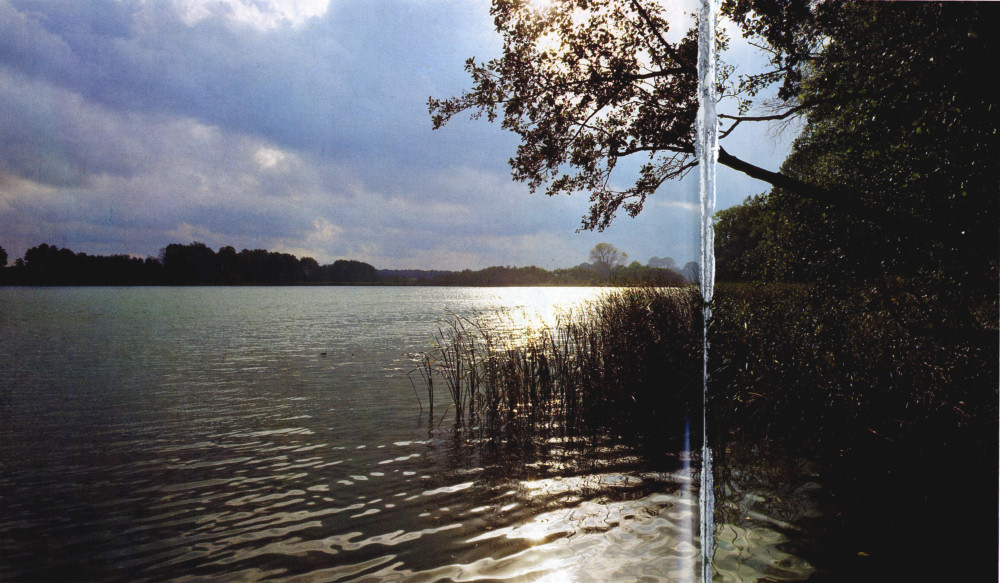

The one-time home of the vanished Baltic Slavs was the melancholic landscape of Mecklenburg interwoven with numerous silver lakes and ponds shaded by pine or deciduous forests. All that remain of the Slavs' legacy are a large number of local names and ruins of castles, hidden in the marshland, on hillocks, peninsulas and on islands in the lakes.

A considerable part of what is today German territory (basically the whole of the German Democratic Republic and a large part of the German Federal Republic as far as Holstein, Hamburg, Hanover, Thuringia and north-eastern Bavaria) was once settled by Slavs. Their tribes flooded this land after the Germanic tribes had moved on at the time of the migration of nations. The Slavs then led a century-long struggle for their independence against the renewed Germanic penetration to the East. This ended with the Slavs being subjugated, exterminated or Germanized. Today all that remains are very small numbers of surviving Lusatian Sorbs, but there are no traces of the Polabian or Baltic Slavs other than numerous place-names and sites investigated by the archeologists.

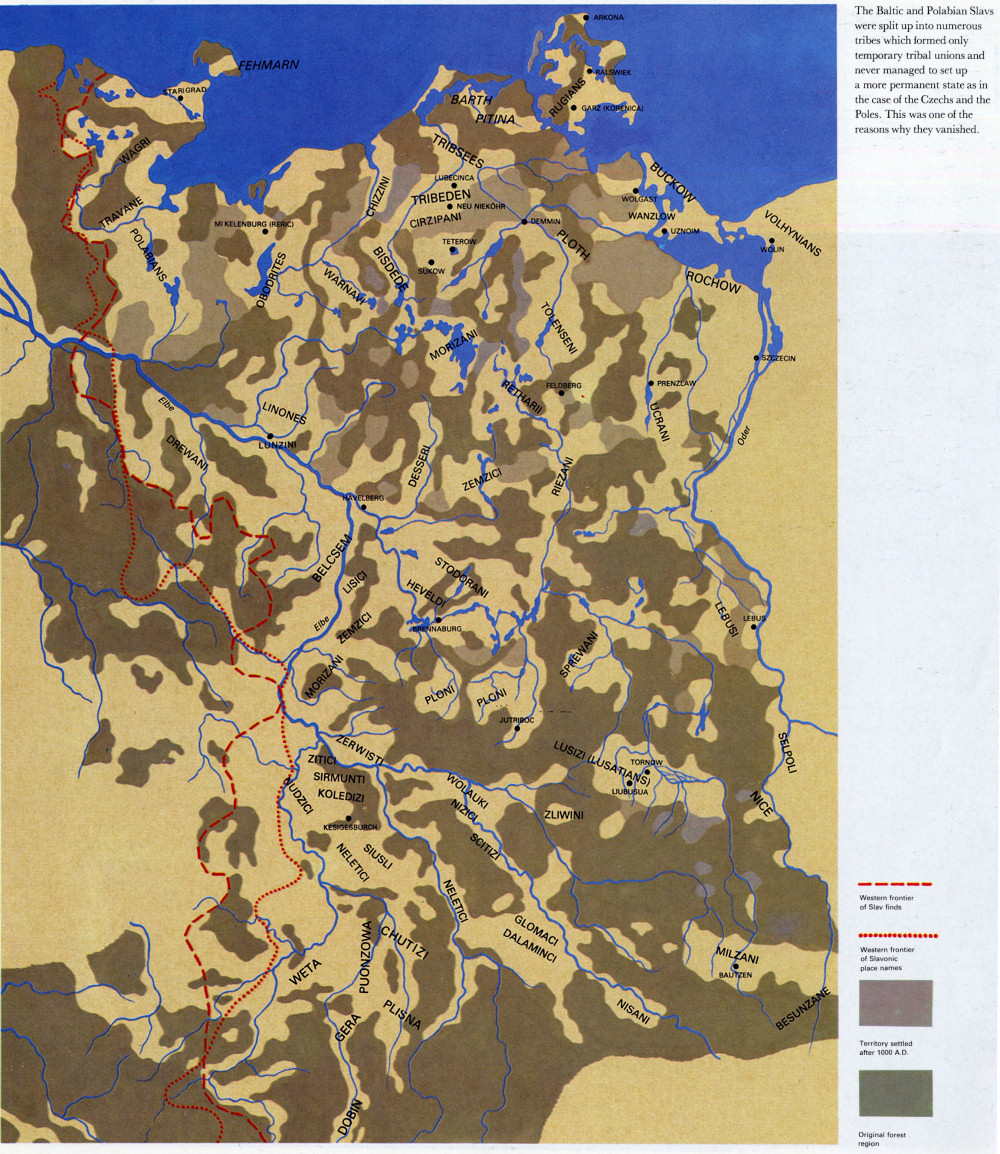

The main cause of this tragic fate of the lost Slav tribes was their lack of political unity and consequent dispersion and ramification into a large number of separate units. They never became organized into a strong state that would have been able to withstand German pressure, as was the case of the Poles and the Czechs. Only two of their groups formed minor unions of tribes: the Veletians (or Liutizi) in Brandenburg and on the coast between the mouth of the Warnow and the Oder, in the tenth and the first half of the eleventh century, and the Obodrites (east Holstein and Mecklenburg [or Mikelenburg]) in the eleventh and the first half of the twelfth century. The Lusatian Sorbs remained permanently divided into individual tribes until they succumbed to the Germans in the tenth century. The Pomeranians (between the Oder and the Vistula) found themselves in the sphere of interest of the growing Polish state from the second half of the tenth century on. For a short period they existed as an independent princedom until, in the end, they found themselves subjugated by the Germans. It proved fatal to all these tribes that neither the Poles nor the Czechs managed to establish a strong state in Central Europe that would have unified all Western Slavs. This had been the dream of Bolesław Chrobry (the Brave) and Břetislav I of Bohemia, for that alone ^could have put up a barrier to the constant German expansion to the east. The Slavs' obstinate resistance to Christianity also played its part. Their dogged determination to worship nothing but their own gods laid these tribes open to the Christianizing efforts on the part of the Franks and Saxons, involving economic and political subjugation. All this finally led to the loss of nationhood.

209

![]()

The Baltic and Polabian Slavs were split up into numerous tribes which formed only temporary tribal unions and never managed to set up a more permanent state as in the case of the Czechs and the Poles. This was one of the reasons why they vanished.

210

![]()

The beauty of the jewelry from the region of the Baltic and Polabian Slavs in no way lags behind goldsmiths' work in the neighbouring Slav countries. This is proved by silver filigree ear-rings in the form of a cross and by a plaited necklace from Niederlandin near Angermünde (eleventh century).

Charlemagne already led a struggle with his eastern Slav neighbours, but he also managed to win them over as allies. He needed the Obodrites, for instance, in his effort to dominate the Saxons. These very Saxons, the immediate neighbours of the North-Western Slavs, involved them in many battles. Developments took a turn when the Duke of Saxony, Henry the Fowler, became King of Germany in 919. His name is linked with the beginning of the Drang nach Osten (desire for eastward expansion) which started nine years later. In his rapid advance Henry managed to conquer Brandenburg, the centre of the Heveldi or Stodorani, subdue the Veletians and the Obodrites and subjugate all the Sorbian tribes between the Elbe and the Saale.

His successor Otto I (936—973) was equally successful. He set up a network of castles and strengthened the German position between the Elbe and the Saale. Making use of the notorious Count Gero, whom he entrusted with the rule over this territory, he enlarged his domain as far as the rivers Neisse and Bober. The Christianization of the Slav tribes was supported by missionary bishoprics established along the borders with the Slavs, from Oldenburg as far as Meissen. The main centre was Magdeburg, to which all the Slavs between the Elbe and the Saale were to be ecclesiastically and politically subordinated.

Otto's plans came to nothing under his successor Otto II (973—983), whose defeat in the struggle against the Arabs in Calabria and death in 983 became a signal for a major Slav uprising. This swept away the German rulers between the Elbe and the Oder and put an end to all efforts for the conversion to Christianity of the local tribes. Only Holstein and the Sorbian territory remained under Germany. According to Helmold's Chronica Slavorum of the twelfth century the leader of the uprising was one Mstivoj, whose grandson Gottschalk organized the Obodrites into a state. Gottschalk was a Christian and co-operated with Archbishop Adalbert of Bremen to convert his country to Christianity in a peaceful manner — a form of missionary work begun by Otto III (983-1002) on the advice of his friend Adalbert, the Bishop of Prague, after the bitter experiences at the end of the tenth century. Gottschalk's aim was to form an independent Christian state on the Baltic coast in a feudal union with the German Empire.

On the initiative of the Veletians there was a new pagan regression in 1066 during which Gottschalk was assassinated and the Obodrites reverted to paganism. It was not until around 1093 that Gottschalk's son Henry defeated the pagans and became ruler of the Obodrites. After his death and a short period of Danish domination the Obodrite principality was divided between Pribislav

211

![]()

and Niklot. Pribislav settled at Lubek (the Slavic predecessor of the present harbour town of Lübeck) and became renowned for his pirate expeditions along the Danish coast. Niklot became the founder of the princely dynasty of Mecklenburg, which in the course of time became German and remained in power until 1918.

This magnificent example of an iron stirrup decorated with silver inlay and gold comes from Baltic workshops east of the Vistula. It was lost by a Slav horseman on the river Havel near Pritzerbe not far from Brandenburg (first half of the eleventh century).

Pribislav's and Niklot's territory was the main goal of a crusade against the pagan Slavs proclaimed by the well-known Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux in 1147. The Saxon nobility enthusiastically participated as they were interested in gaining new estates. The crusade was none too successful from a military point of view, but it broke the strength of the Slav tribes when large stretches of their country were laid waste. It ended with Pribislav and Niklot accepting Christianity and acknowledging the sovereignty of Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony. For a time after the death of the Brandenburg Prince Pribislav in 1150, the Veletian territory came under the rule of Albert the Bear.

The last bastion of Slavonic paganism and independence — the island of Rügen — fell in 1168 to the Danish King Waldemar when he conquered Arkona. The entire region of the North-Western Slavs was then open to extensive colonization from the West, and thus it became Germanized.

212

![]()

1. THE LUSATIAN CENTRE AT TORNOW

The few Lusatian Sorbs remaining today live in Upper Lusatia in the vicinity of the town of Bautzen and in Lower Lusatia in and about Cottbus. Once the Lusatian Sorbs were to be found in the whole southern area of the German Democratic Republic between the Oder, the Elbe and the Saale. Their villages even lay to the west of the Saale in north-eastern Bavaria and in northern Bohemia. They left behind a large number of settlements, cemeteries and fortified centres, where excavations have been carried out. One of the most important and most thoroughly excavated sites is the hill-fort of Tornow in Lower Lusatia. It best documents the culture of the Lusatian Sorbs in the period before they lost their independence.

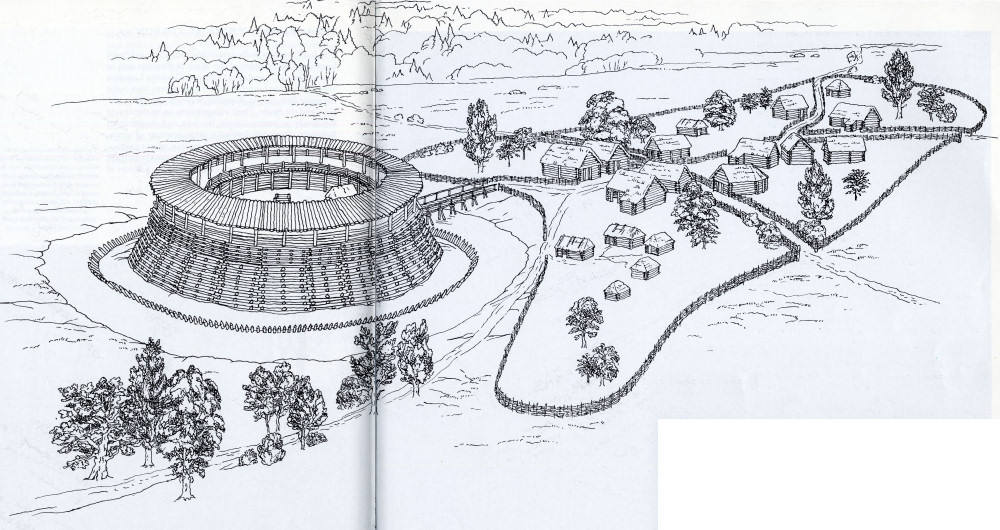

The Lusatian tribe settled in the flat landscape with lakes and broad strips of forests which divided them from the territory of other related tribes. In the seventh to tenth century their land (today's Lower Lusatia) was densely scattered with hill-forts of a circular ground plan, evidence of an independent life which did not last long.

Tornow lies on the territory of the Lusatian tribe south of the Spreewald. The southern tribal border ran along the Lusatian Hills, which divide Upper and Lower Lusatia. To the west their territory ended at the river Dahme and in the east along a bend in the middle course of the Spree near Cottbus. The landscape was flat with numerous watercourses and wide strips of forest that marked out other tribal areas. The Milzani lived to the south, the Sprewani to the north, in the east were the Selpuli and westwards lay the region of the Nisani.

213

![]()

Small hill-forts lie scattered all over this region. They have a circular ground plan no more than 30 to 40 metres (35 to 45 yards) in diameter and are located some 3—4 kilometres (about 2—2 1/2 miles) apart. Most of them date from the time when these tribes lived an independent life, but from the tenth century on the whole region frequently changed hands and belonged in turn to the German or the Polish feudal state. The Lusatian tribe was first mentioned by name in the middle of the ninth century by the Bavarian Geographer, who cites twenty castles and their domains on this territory. Strangely enough, in contrast to other facts he gives, this tallies basically with what the archeologists found. Chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg mentioned a castle by the name of Liubusua conquered by Henry the Fowler in 932. The other names are not known to us, though one of them must, however, have been Tornow in the Calau district.

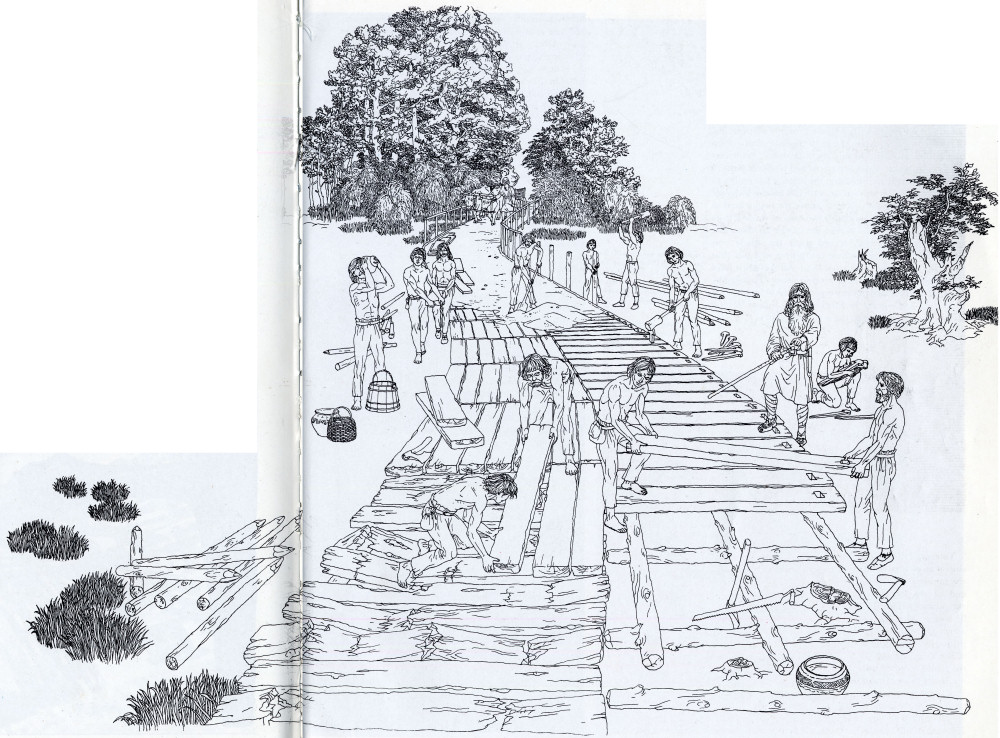

In the years 1961 to 1962 and in 1965 to 1967 excavations were carried out not only of the hill-fort itself but of the settlements in its surroundings so that a picture was built up of the development of the whole settled area. From this it became possible to draw important economic and social conclusions.

The hill-fort was constructed in two phases, which could be distinguished in the structure of the fortifications and the buildings inside the fort. In the earlier phase a construction of stakes stood behind the wooden frontal wall and there were casemates in the inner ward, where there stood dwelling houses, a mill and a well. It seems that the only permanent inhabitants were the family of the governor or warden of the castle, while the people in the surrounding villages used the castle casemates only in times of emergency.

This earlier hill-fort was destroyed by a fire, which must have broken out very suddenly as the inhabitants did not have time to remove supplies, which were burnt. A new castle was built relatively quickly on the ruins of the one that had burnt down. The new one followed the general layout of the older castle, but its fortifications were stronger while the inhabited interior area grew smaller. A large part of this inner area of the hill-fort was taken up by granaries. They replaced the casemates along the edge of the fortifications and contained large quantities of grain. In the centre of the hill-fort stood one large building, a wooden house with two storeys and a cellar, a small outbuilding and close by was a well. Three other dwelling houses were set into the fortifications alongside the granaries.

The difference between the earlier and later phase of Tornow can be explained by changes in social conditions. The larger inner area of the older fort, guarded simply by the family of the warden, provided the possibility of temporary abode for a larger number of people and their property. This points to its function of refuge for the peasant population in the surroundings where social differentiation was only just beginning. In the second phase the castle grounds were built up in such a manner that there was no longer room for many other people. The entire central area was taken up by the residence of the lord of the castle who had a small retinue of about twenty men, who occupied the dwellings set into the fortifications. The rest of the area was taken up by storage facilities for food, mainly grain, levied from the population around the castle. In the same manner they acquired cattle (for bones form a large part of the refuse), honey, linen, furs, textiles, and other products made by village craftsmen, such as pottery, iron tools

214

![]()

and weapons, wickerwork, as well as articles made by coopers and carpenters. They traded for millstones, made of porphyry, which is to be found in western Saxony, the region of the Chutizi. An analysis of finds using the radio-active C 14 carbon method dates the older castle at Tornow to the seventh and eighth centuries. The later one was built at the end of the eighth century but did not last longer than the first half of the ninth century when it, too, was laid to ashes by a fire.

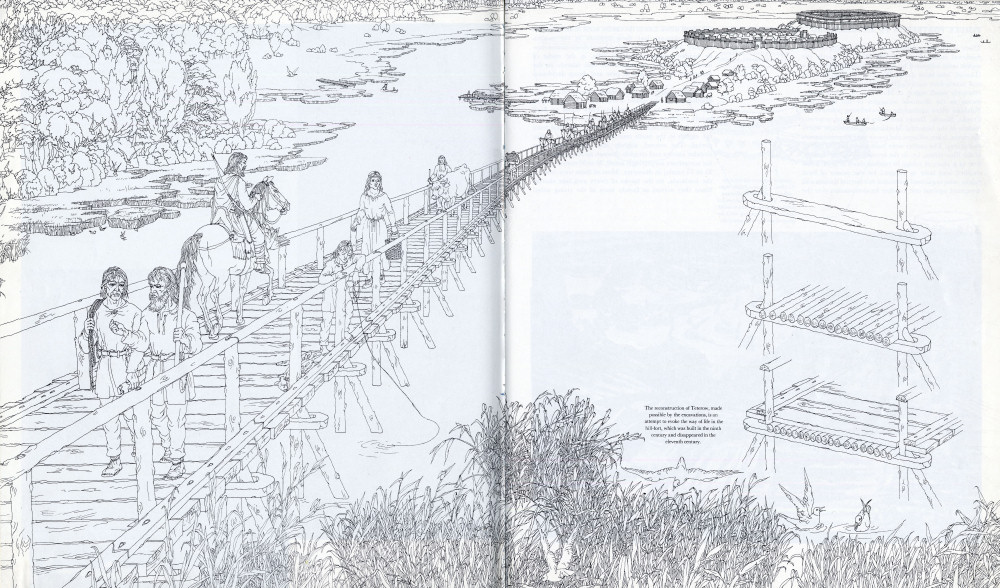

Excavations at Tornow in Lower Lusatia have made possible the reconstruction of the hill-fort and adjacent settlement. This documents the economic and social conditions of the Lusatians in the seventh to ninth century.

The inhabitants of Tornow dug a well inside the hill-fort and lined it with timber and stones (seventh to ninth century).

215

![]()

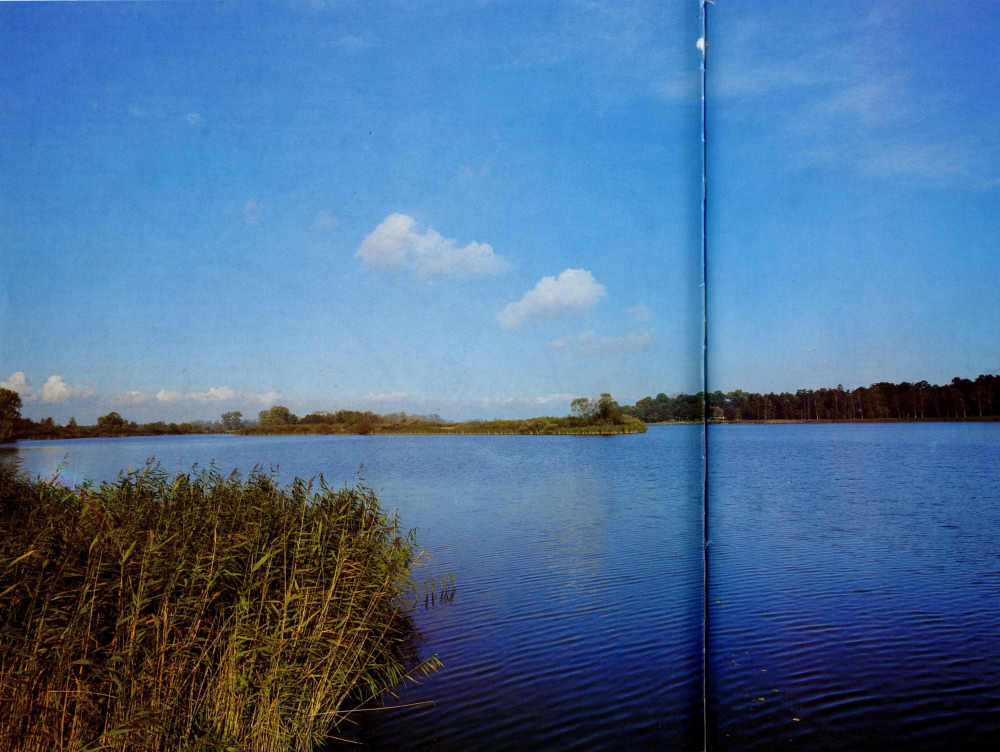

The Teterów hill-fort of the Cirzipani tribe is a typical example of Slav fortification built on islands in the middle of the Mecklenburg lakes. It was linked to the mainland by a 750-metre (820-yard) long bridge.

Three villages, which shared its fate, were linked to the hill-fort. Typical of the earlier phase are large farmsteads which probably belonged to single great families. On the other hand, in the later phase the large houses were replaced by a number of smaller dwellings. These were used by a lower stratum of the population dependent on the ruler of the castle. The fate of this region thus reflects on a small scale the social development of the entire Lusatian Sorbian region in the early Middle Ages.

Thanks to the properties of the soil the bridge at Teterów hill-fort is in excellent condition so that it is still possible to walk over it today, 1000 years later. All that is missing is the balustrade.

217

![]()

The reconstruction of Teterow, made possible by the

excavations, is an attempt to evoke the way of life in the hill-fort, which was

built in the ninth y century and disappeared in the eleventh century.

218-219

![]()

2. TIMBER FORTRESSES IN MECKLENBURG

There is no other place where such numbers of early medieval castles have survived than the north, the region once inhabited by the Obodrites and Veletians (Liutizi) who have completely died out. One hundred and ninety-four such castles have been counted in the relatively small region of Mecklenburg. These monuments to the dramatic struggles of the Baltic and Polabian tribes against the overwhelming power of the Franks, Saxons, Danes and Poles form a characteristic feature of the beautiful Mecklenburg landscape where the rivers, lakes, villages and towns bear Slavonic names to this day. The castles were built soon after the arrival of the Slav tribes, i.e. in the seventh to eighth century, first as a place of refuge in restless times of inter-tribal conflict, and later as support for the power of local rulers, who organized resistance to external threats and competed against one another for domination over the subjected tribes. Life in the castles came to an end when their inhabitants lost their freedom in the twelfth century. The ruins of looted and burnt down castles now lie hidden among forest-clad hills, in the midst of inaccessible bogs, on peninsulas and islands in the numerous lakes, hidden in pine and damp deciduous woods.

Another important hill-fort of the Cirzipani, at Behren-Lübchin, might rightly be called the Mecklenburg Pompeii. The timber fortifications and buildings from the eleventh to twelfth centuries sank into the bog, which has preserved them up to the present day.

The Slav castles in Mecklenburg underwent a certain development in the course of centuries. The oldest lie in the eastern parts of the region. They stand on high points and have extensive fortifications. None of these castles is mentioned in written records. They date from the eighth to the ninth century if not from an earlier period. The second, slightly later group comprises circular castles and citadels (known as Ringwalt). They are sometimes surprisingly small, 30 to 50 metres (about 35 to 55 yards) in diameter. Most of them were built in the lowlands, on the banks of rivers and lake shores. Since they served as family seats of the rising tribal

220

![]()

nobility they reflect the complex social relations in the ninth to tenth century. The extensive and complex hill-forts of the third group are partly contemporary with the former, but lasted into the eleventh and even the twelfth century. Finally, the last type are castles established in barely accessible places, especially on islands in lakes as silent witnesses to the last desperate struggle of the Slav tribes in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

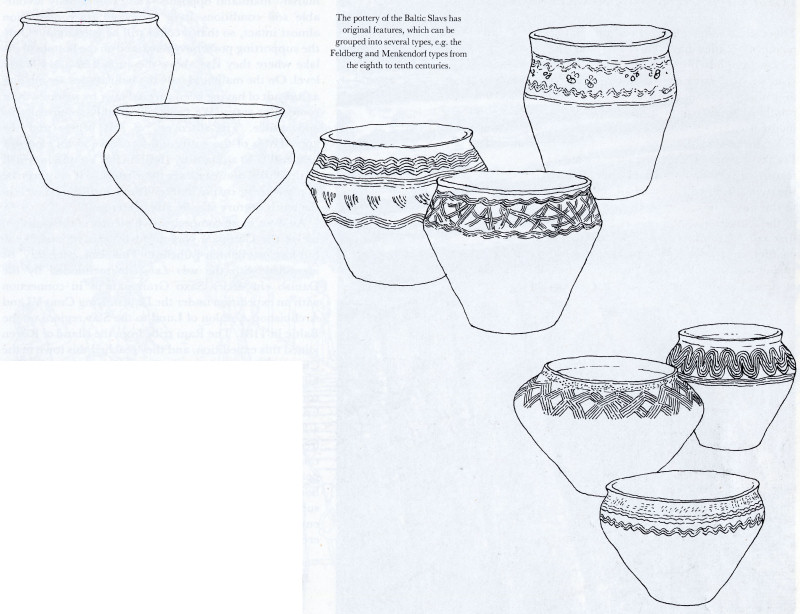

The pottery of the Baltic Slavs has original features, which can be grouped into several types, e.g. the Feldberg and Menkendorf types from the eighth to tenth centuries.

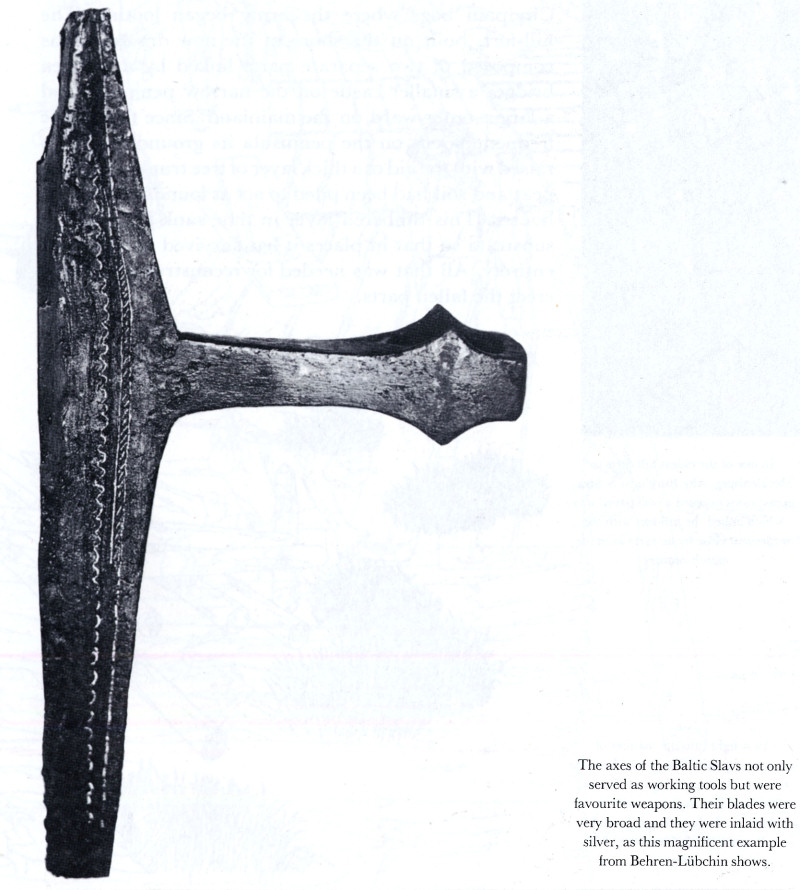

The axes of the Baltic Slavs not only served as working tools but were favourite weapons. Their blades were very broad and they were inlaid with silver, as this magnificent example from Behren-Lübchin shows.

Intensive investigations have been carried out on the territory of one of the main tribes of the Liutizi union, the Cirzipani. They lived in a marshy region between the rivers Reknitz, Trebel and Peene. The most important excavations were undertaken on hill-forts at Teterów, Behren—Lúbchin, Sukow and Neu-Nieköhr.

221

![]()

In one of the oldest hill-forts in Mecklenburg, Alte Burg near Sukow, excavations exposed a well paved way which linked the hill-fort with the settlement close by as early as in the eighth century.

Teterów hill-fort was constructed on a picturesque site on an elongated island in the centre of a lake bearing the same name. The castle proper stood at the northern end of the island. It was not very large and was surrounded on all sides by a mighty wall, which is still 8 metres (over 26 feet) high today. The larger outer ward, surrounded by a similar wall, was inhabited primarily alongside the fortifications while the inner hill-fort was densely built-up. The remaining parts of the island revealed traces of an open village, from which a raised timbered road led to the marshy shores.

A great surprise for the archeologists was the discovery that this road was, in fact, the end of a bridge, which crossed the water of the lake to a total length of 750 metres (820 yards) and continued over a stretch of marshy mainland opposite. The exceptionally favourable soil conditions have preserved its construction almost intact, so that it could still be used today. Only the supporting posts have remained on the bottom of the lake where they rise above the surface at a low water level. On the mainland only the balustrades are missing as a result of having been covered over by a causeway at some later stage. We can thus reliably reconstruct its appearance. The discovery of this bridge and the appearance of the entire hill-fort serve as an eloquent illustration to a report by Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb in which he described Slav castles in these regions. It may even be that one of the castles that he visited during his travels in the tenth century was, in fact, Teterów.

An even more comprehensive picture of the vanished life of the Cirzipani was given by excavations of the hill-fort at Behren-Lübchin. This can probably be identified with the urbs Lubekinca mentioned by the Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus in connection with an expedition under the Danish King Cnut VI and Archbishop Absalon of Lund to the Slav regions on the Baltic in 1184. The Rani tribe from the island of Rügen joined this expedition, and they reached this town in the Cirzipani bogs where the army began looting. The hill-fort, built on the shore of the now dry lake, was composed of two separate parts linked by a wooden bridge: a smaller castle on the narrow peninsula and a larger outer ward on the mainland. Since there were frequent floods on the peninsula its ground level was raised with the aid of a thick layer of tree trunks on which peat and soil had been piled to act as foundation for the houses. This timbered layer in time sank into the soft substrata so that in places it has survived almost in its entirety. All that was needed for reconstruction was to erect the fallen parts.

222

![]()

An insight into the manner of constructing roads was gained from the remains of the paved way at Sukow, which survives in good condition. It led across the local boggy lands for a distance of 1,200 metres (1,300 yards).

The large number of objects found here include valuable wooden articles which do not usually survive in other soil conditions: shovels, cudgels, even axes with handles, wooden dishes, buckets, wagon wheels, sticks with decorative handles, little carved figures (e.g. a dragon's head which was probably an ornament on a wagon or sledge) and other objects that provide an indication of the level of local craftsmanship in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

223

![]()

Iron shackles with a lock, found at Neu-Nieköhr hill-fort, were used to bind prisoners or slaves (eleventh to twelfth century).

Hill-fort Alte Burg near Sukow is one of the most ancient in Mecklenburg. Here was a chance to gain an insight into the manner of road building. There was a timbered road, 1,200 metres (over 1,300 yards) long, that linked the castle hidden on a hillock in the bog with the unfortified settlement. The timbered way has survived in excellent condition in the wet soil. It was rebuilt on several occasions. The most interesting alterations date from the period when the castle was the centre of an estate with a whole group of settlements. There was a substratum of tree trunks laid crosswise on top of one another. On this lay thick, broad, painstakingly cut planks, which were attached with oak posts to the surrounding terrain along the edge. The result was a road of double width strewn with fine sand which rose half a metre (nearly two feet) above the boggy land as a causeway. It was possible for two wagons to use it to go simultaneously in and out of the castle. In this more recent form the road served until the castle was abandoned, when it became overgrown and has thus survived in almost its original form. All this must have taken place in the eighth to ninth century. To judge by finds of undecorated pottery typical of the older hill-forts and their settlements in Mecklenburg, Sukow fortress might even date back to the seventh century.

224

![]()

Until the Danish invasion in 808 Reric, probably to be identified with hill-fort Mecklenburg, was the destination of Frankish trade caravans. Later it became the centre of the Obodrite princes.

225

![]()

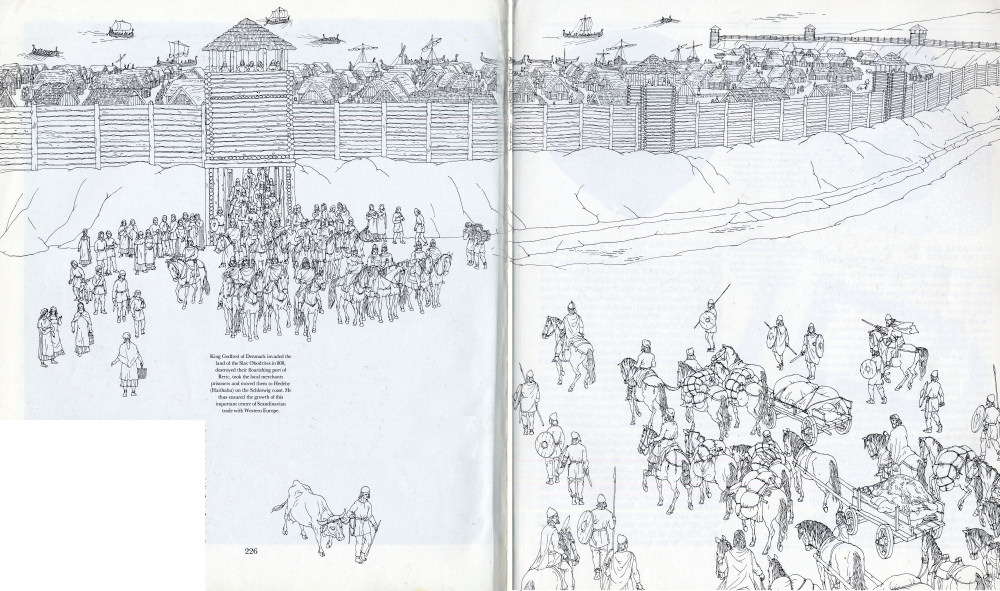

King Godfred of Denmark invaded the land of the Slav Obodrites in 808, destroyed their flourishing port of Reric, took the local merchants prisoners and moved them to Hedeby (Haithabu) on the Schleswig coast. He thus ensured the growth of this important centre of Scandinavian trade with Western Europe.

It has already been said that there existed a Liutizi union. After the victorious uprising of the Slav tribes of the Polabian and Baltic regions in 983 it was joined by the Cirzipani and also the Chizzini, Tolenseni and Retharii, and played an important political and military role until the middle of the eleventh century. Then civil war broke out between the Chizzini and the Cirzipani on the one side and the Tolenseni and the Retharii on the other, which ended with the first two being drawn into the realm of the Obodrites. As late as in 1151 we still hear of an unsuccessful struggle on the part of these two tribes against the Obodrite Prince Niklot. Soon after, they shared the fate of all the Slavs between the Elbe and the Oder, who finally lost their independence and in the course of the next two or three centuries even their nationhood. All that remains are the ruins of timber castles, unearthed by the shovels of the archeologists, which provide evidence of their former glory.

226-227

![]()

3. SEAFARERS AND PIRATES IN THE BALTIC SEA

Ships and harbours of the types we found in the eastern parts of the Slavo-Baltic coast were also built in the western regions, in Mecklenburg and Holstein. Records speak of the existence of the oldest known Slav harbour, Reric, on the territory of the Obodrites. Its name is Danish and means "reed-bed", but it was an Obodrite centre which the Saxons called Mikelenburg, from which the present-day Mecklenburg is derived. The original Slavonic name was Veligrad. The power of the Obodrites grew after they fought against the Saxons as allies of Charlemagne. They were given land as far as the mouth of the Elbe, where Hamburg now stands. The Frankish merchant caravans which crossed the region from the Elbe to the Baltic Sea made this Reric-Mecklenburg their destination. Such rivalry in trade was regarded with dislike by the Danish King Godfred. In 808 he invaded the territory of the Obodrites, destroyed Reric, whose wealth had been a thorn in his side, and moved the local merchants to Hedeby (Haithabu), a harbour town that he had founded on the Schleswig coast. From that time on Hedeby, which has been the centre of interest of German archeologists for several decades now, became a centre of Viking trade with Western Europe. But Reric did not vanish. It became the seat of the Obodrite princes and is still mentioned in the twelfth century, even though its importance had receded into the background by that time.

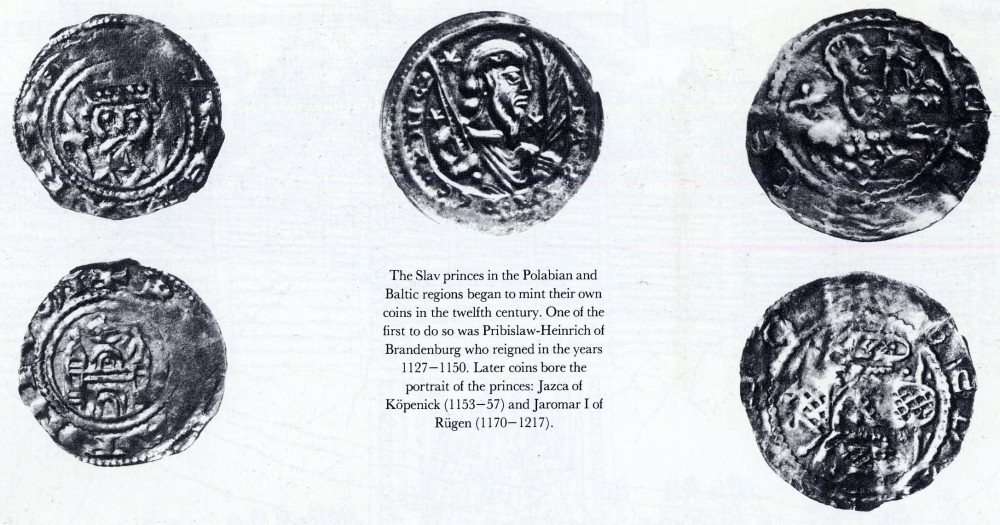

The Slav princes in the Polabian and Baltic regions began to mint their own coins in the twelfth century. One of the first to do so was Pribislaw-Heinrich of Brandenburg who reigned in the years 1127-1150. Later coins bore the portrait of the princes: Jazca of Kopenick (1153—57) and Jaromar I of Rügen (1170-1217).

The most exposed westerly tribe of the Baltic Slavs were the Wagri. Their main centre was Starigrad, called Oldenburg by their western neighbours. It grew up in the seventh or eighth century and developed into a harbour town that carried on a brisk trade with Scandinavia. This fact is proved, among others, by a number of treasures found in its surroundings. Like Mecklenburg and other harbour towns Oldenburg did not lie right on the coast but at a distance of about five kilometres (about three miles) from Kiel Bay and roughly fifteen kilometres (about nine miles) from Lübeck Bay, which could be reached by ship along the Oldenburg canal. In 968 a bishopric was founded here as the centre of the mission to the local Slav tribes. In the eleventh to twelfth century Starigrad and the whole of Wagria became part of the Obodrite state and was then gradually overshadowed by growing Lübeck, which took over the role played by Starigrad-Oldenburg and Reric-Mecklenburg in the twelfth century.

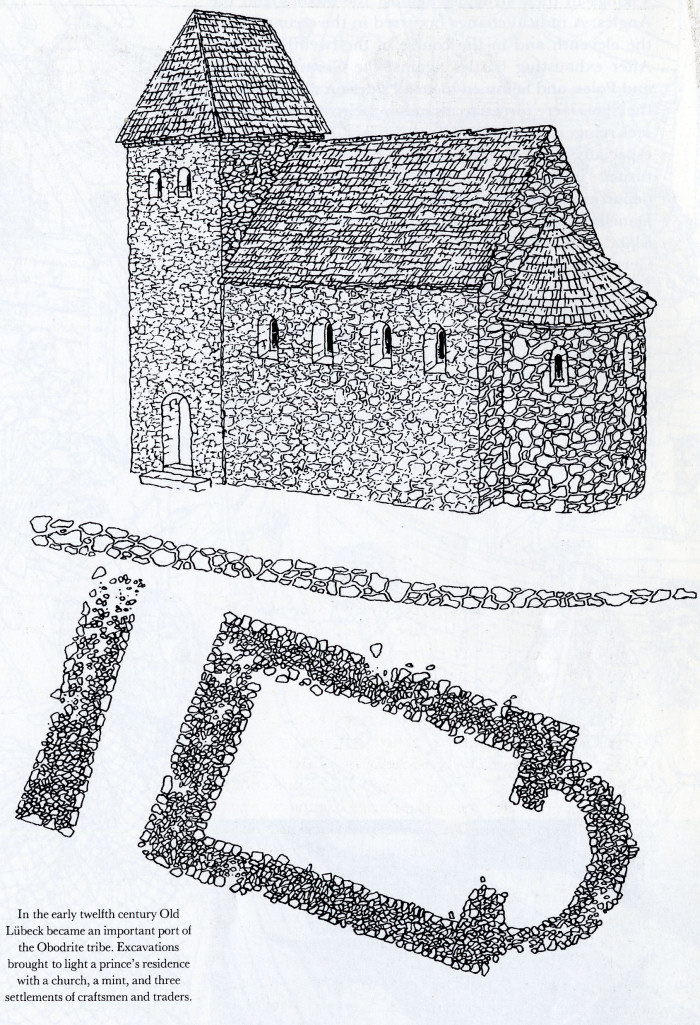

Old Lübeck lay four kilometres (about two and a half miles) to the north of the later medieval town. It became prosperous under the Obodrite Prince Henry (1093— 1127), who chose it for his residence. The town has frequently attracted archeologists, who clarified its situation during major excavations in the years 1947 to 1959. Inside the castle walls they unearthed the foundations of a church with an elongated ground plan and in it eight tombs of princes. They contained eleven gold discs and gold hairpins. Next to the church stood the princes' palace and close by were the living quarters of the garrison, a mint, goldsmiths' workshops, storerooms, granaries and a well. Outside the walls lay three settlements, in which the craftsmen, servants and merchants dwelt. They were mainly of Danish and German nationality and, according to the Chronicle of Helmold, they even built their own church. Old Lübeck did not flourish for long. The settlement vanished before the middle of the twelfth century together with the

228

![]()

Obodrite state, and in 1158 Henry the Lion founded the present town of Lübeck close by.

?

The Slav tribes had a good deal of contact with the Scandinavian region, both in the form of trade and in warfare. This is proved by a bronze disc with a bas-relief of a mythical beast, done in the Jelling style (Carwitz, eleventh century).

In the early twelfth century Old Lübeck became an important port of the Obodrite tribe. Excavations brought to light a prince's residence with a church, a mint, and three settlements of craftsmen and traders.

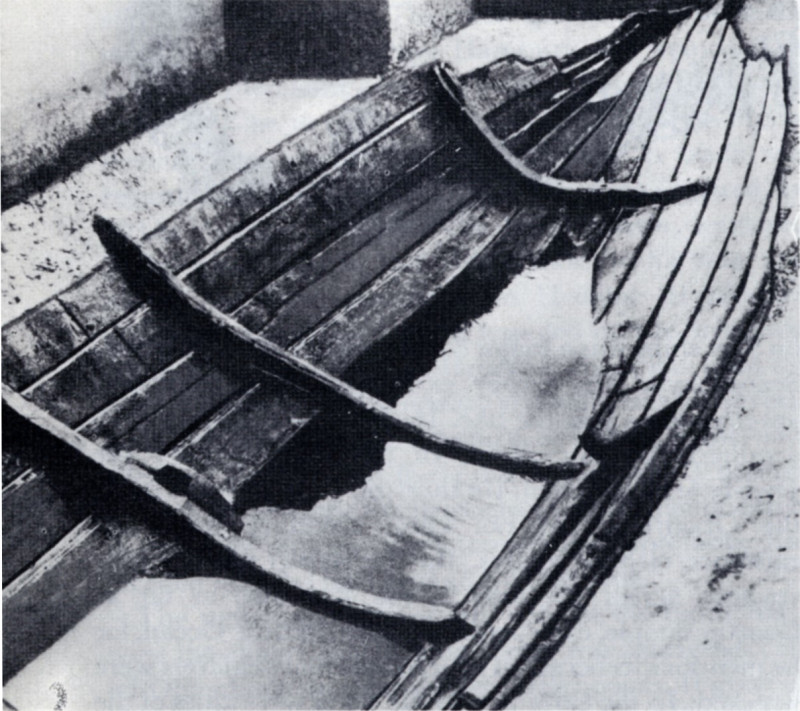

The spiritual centre of the Baltic Slavs was the island of Rügen with the Svantovit temple at Arkona. The location and shape of the island with its numerous bays where ships could run ashore made Rügen ideal for seafaring. One of the harbours was discovered at Ralswiek in Jasmund Bay. The settlement was protected by marshland and extended over more than half a kilometre (about 550 yards). It was inhabited by both the local population and foreign merchants who brought, among other imports, Scandinavian fibulae and Norwegian talc. Silversmiths were active here and finds of writing tools suggest that people knew how to write. Seafaring was confirmed when three ships from the ninth or tenth century were discovered. The largest was 13 to 14 metres (nearly 15 yards) long, 3.4 metres (3.7 yards) wide and was constructed of oak battens joined with iron rivets and attached to the frame of the ship with wooden pegs. The holes were caulked with hemp fibre and resin. This ship was of a type used to carry cargo.

The Slavs on the Baltic Sea were good seafarers and managed to establish a whole network of fortified, economically prosperous harbours. For that reason the Vikings did not manage to gain control over the southern coast of the Baltic even at the time of their greatest expansion nor did they settle permanently here as they did in the British Isles, Iceland, Normandy, Sicily and in Eastern Europe. By contrast to the Vikings the Slavs at the onset were not interested in piracy. They had no reason to be as their land was far more fertile than Scandinavia. Chronicles relate that even vines grew in Pomerania. Agricultural produce transported on Slav ships was a major commodity in their trade with Scandinavia where they exchanged it for weapons, jewelry, coins and the like. In this way the Slavs even acquired Arabian silver. In the tenth century the Jewish-Arab merchant Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb, who visited the Obodrites, did not know anything about the existence of Slav pirates. But he speaks of their long voyages across the seas to the Russians, as far as Constantinople, even perhaps on the Atlantic Ocean, for he mentions icebergs, on which some Slav seafarers were wrecked. In the early period the Slavs were allies of the

229

![]()

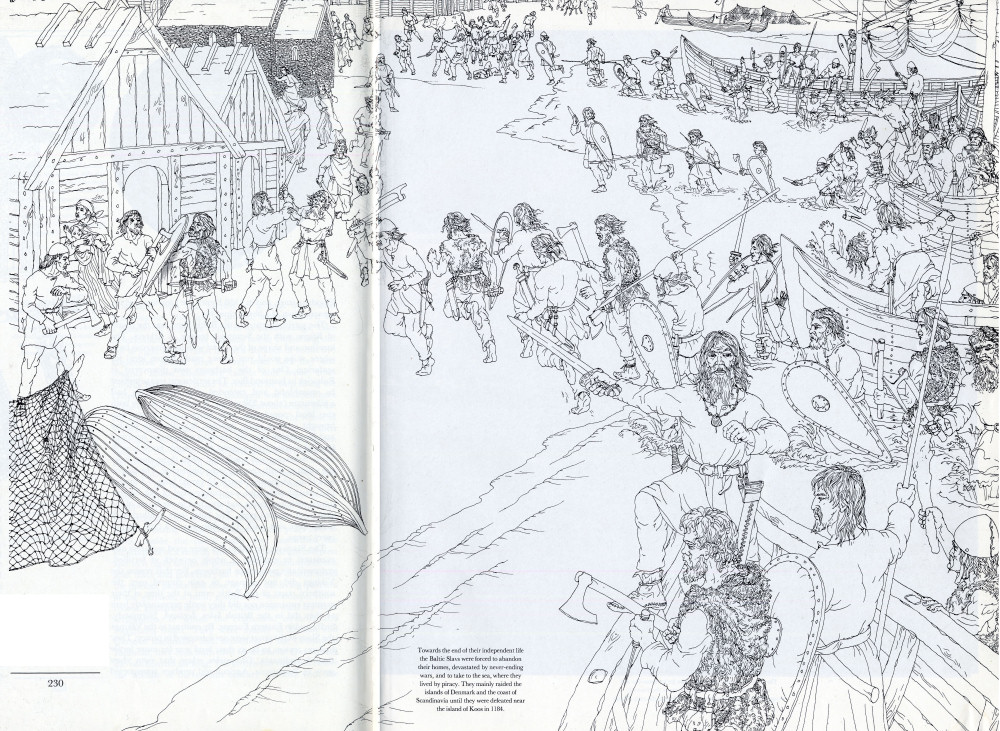

Vikings in their struggles against the Saxons and the Angles. A radical change occurred in the second half of the eleventh and in the course of the twelfth century. After exhausting battles against the Germans, Danes and Poles, and hemmed in on all sides on the mainland, the Slavs were forced to abandon their ravaged homes, seek refuge on the sea and live by piracy. Some harbours, especially those on the islands of Fehmarn and Rügen, turned into feared pirates' nests and became the departure points for devastating raids to the vulnerable Danish islands, the Swedish and Norwegian coast, the island of Gotland and on Lübeck, colonized by the Germans. A change of fortune took place in the year 1157 when a large Slav fleet of 1,500 ships was wrecked in a storm off the Norwegian coast. Since this weakened the power of the Slavs at sea, King Valdemar of Denmark was able to begin a ten-year offensive against the main base of the sea pirates on the island of Rugen. After the fall of Arkona in 1168 the Pomeranian fleet under Bohuslav suffered a heavy defeat by the Danes off the island of Koos in 1184. This disaster put a definite end to the activities of the Baltic Slavs at sea.

The ships of the Baltic Slavs resembled those of the Vikings, but they had a flat bottom, a shallower draught, and the mast with the sails was moved further forward. A wreck found at Ralswiek on Rügen was 13—14 metres (nearly 45 feet) long and 3.4 metres (about 11 feet) wide (ninth to tenth century).

230

![]()

Towards the end of their independent life the Baltic Slavs were forced to abandon their homes, devastated by never-ending wars, and to take to the sea, where they lived by piracy. They mainly raided the islands of Denmark and the coast of Scandinavia until they were defeated near the island of Koos in 1184.

231

![]()

The coast of the Baltic Sea is attractive for its dream-like and melancholic beauty which seems to evoke the dramatic struggle and tragic events that took place here in the early Middle Ages.

232-233

![]()