Chapter 6. Religion, Architecture and Art

- From Arian to Catholic 183

- Longobard Builders and Buildings 190

- Longobard Art and Sculpture 199

Chapter 7. Longobard Heritage: Benevento and Beyond

- The Fate of the Beneventan Principality 206

- State and Society in Longobard Southern Italy 211

- Coinage and Economy 219

- Beneventan and Late Longobard Culture 221

- From Liutprand to the Lega Lombarda 225

- Words and Traditions: Longobard Survivals 229

Chapter 6. Religion, Architecture and Art

. . .

Longobard Art and Sculpture

Many churches and monasteries in Italy display, or incorporate in their walls, fragments of carving from stone or marble chancel screens, altar fronts, pulpits or ciboria, which may offer the sole indication of an early medieval, perhaps Longobard, phase of embellishment. These reliefs are generally decorated with interwoven bands or vines framing bunches of grapes, leaves or flowers, often with doves in attendance; on more elaborate reliefs, the interlace work creates a border for depictions of such Christian symbols as peacocks, deer or lambs and, occasionally, of less obviously Christian elements such as fantastic beasts, griffins, sea monsters or dragons (pl. 36). Far less common are carvings depicting human figures, particularly secular ones; representations of Christ and the Virgin do occur, for example on the Altar of Ratchis at Cividale (see pls 19 and 22).

Inevitably there are problems with dating such pieces and, too often, they are simply assigned to a documented building phase. Attribution is more secure only with pieces bearing inscriptions: tombstones, dedications, sarcophagi or church fittings, such as the splendid Altar of Ratchis, dated to c.745, or the font and cover attributed to bishop Callistus, but in fact executed under the patriarch Siguald in c.770. When secure dates can be assigned, we then have temporal settings for the associated designs and can attempt to tie in uninscribed pieces.

200

Plate 36 Beautifully executed figurative screen panels of the first half of the eighth century, from the royal monastery of S. Michele alla Pusterla, Pavia. (Musei Civici di Pavia, Castello Visconteo.)

However, many of the basic designs had a long currency, running well into the Carolingian period and merging with early Romanesque elements from the late tenth century. Nevertheless, it is clear that such works were being carved from the reign of Liutprand onwards, and thus before the appearance of similar artwork in Byzantine and other non-Longobard areas of Italy. This need not imply that the ideas and forms were all originally Longobard; in fact, many of the designs have their roots in early Christian and Byzantine art. But there is a clear Germanic input in the use of the interlace and of the fantastic animals, so evident in much of Longobard metal-work, which suggests a healthy merging of artistic skills.

201

The Germanic elements may not be all Longobard, either, for similar designs can be viewed in the illuminations of British and Irish manuscripts of the seventh century where they probably were Anglo-Saxon, rather than Celtic, features. In this respect, we must recall the Irish involvement in the foundation of Bobbio in Italy and of monasteries in Francia, and also the documented pilgrim traffic from Britain to Rome via Langobardia. [12]

The dating and derivation of more adventurous art forms, notably figured frescos or stucco work, such as can be seen in the famous Tempietto, the small church of S. Maria in Valle at Cividale (pl. 37), are open to even greater art-historical debate. The problem is that the majority of surviving art works cannot readily be fixed within the true Longobard period: even in the case of the Tempietto, dating wavers between the mid-eighth century and the early ninth century, and thus between Longobard-Byzantine and Carolingian. [13] Scholars do, at least, agree on a major revival of the arts under Liutprand from the second decade of the eighth century, and, thus, well before a similar revival of classical art forms in Rome. Longobard art continued to flourish and was maintained well into the second half of the century, and even after the fall of the Longobard kingdom, it survived both in the north and in the new southern states. The ‘revival’ probably hides a low-key continuation of these arts throughout the seventh century - churches such as S. Maria Antiqua in the Rome Forum certainly provide evidence for the persistence of high quality work, while figured murals (non-religious in design) are recorded by these dates.

12.

· Peroni, ‘L’arte nell’età longobarda’ in Magistra Barbaritas, 229-97;

· Romanini, ‘Scultura nella “Langobardia maior”: questioni storiografiche’, Arte Medievale, V (1991);

· M. Righetti Tosti Croce, ‘La scultura’ in I Longobardi (exh. cat., 1990), 300-24.

A large body of the relevant material is collated in the series Corpus della Scultura Altomedievale.

13. S. Tavano, Il Tempietto longobardo di Cividale (Udine, 1990).

202

. . .

Chapter 7. Longobard Heritage: Benevento and Beyond

. . .

State and Society in Longobard Southern Italy

Within the principality of Benevento, towns and lands were supervised by gastalds or counts: since the prince himself had formerly been the sole duke, the gastalds

212

must have been dependent appointments from the start - thus in contrast with the pattern discussed for the northern kingdom, where gastalds had come to be appointed by the King to curb ducal excesses. Gastald control of major border fortresses, such as Acerenza and Capua, was, however, intensified by the growing territorial insecurity of the ninth century, and inevitably these nobles came to seek independence or, in some cases, even the throne. In their desire to secure allegiance, the princes were forced to cede more and more rights to these counts, leading to increasing decentralization of the state. Civil war and the formation of the breakaway states of Capua and Salerno show the Beneventan edifice crumbling already by the mid-ninth century. Fragmentation continued even within these reduced areas, as for example in Capua, where the sons and grandsons of Landulf I all built their own independent castles. Whilst princes could not always secure dynasties, for the most part they tried to secure territorial control by giving gastaldates out to family members. As in the case of Capua, however, loyalty was not easily gained, and private power progressively ate away at public power. [4]

It is difficult to discern the rest of the cast behind these leading actors: at Benevento (and, in imitation of this, at Salerno and Capua), the court comprised an elaborate array of officals, drawn from the ranks of the urban nobility, with titles borrowed from Pavian and Byzantine court ceremony. But many of these posts appear to have fallen redundant by AD 900, signifying a loss in resources and a rise of military over civil offices. Academic posts at the courts also disappear around this date. Longobard society was by then heavily feudal in character, dominated by a series of petty counts or lords, all more or less autonomous, housing local peasant populations within their castles.

4. Wickham, Early Medieval Italy, 159-62, notes that ‘eleventh century documents for Molise reveal a completely private world of counts freely making cessions to monasteries of what seems to have been public land’.

213

An important element in these Longobard states was the dominance of the countryside, and a relative absence of large urban centres. In the Beneventan and Capuan principalities rural castle-towns dominated small landed territories and were governed by single noble families. In contrast, on the Campanian coast the cities of Naples, Salerno and Gaeta were virtually islands with very little control over their hinterlands. In Byzantine Apulia, the theme of Langobardia consisted of numerous semi-autonomous cities and villages in which local families were granted offices and titles, and which were controlled by taxation and by the chief Byzantine officials, the catepans or strategoi. These officers oversaw rather than stifled local society, and although rebellions did occur, apparently, they were not attempts to remove Byzantine rule. As in seventh- and eighth-century Byzantine northern Italy, the impact of actual Greek culture was fairly low, and Longobard law and nomenclature remained to the fore in Apulia. This may suggest that the Longobard percentage of the population was high, perhaps reflecting a settlement of displaced northerners, but we have no evidence to prove this. Certainly by the year 1000 the Apulians were fairly cosmopolitan: the Norman chronicler William of Apulia, for instance, tells of the meeting on Monte Gargano between Melo, an exiled rebel from Bari, and a group of Norman knights, fresh from crusading exploits. Melo is described as a freeborn citizen, Longobard by birth, dressed in Greek fashion but with a turban on his head. Interestingly, he presents himself mainly as a man of Bari, highlighting the emergence of urban identities and loyalties in the Byzantine south, to be set in line with the development of the north Italian communes. Prosperity and patronage are reflected in Langobardia by the construction of substantial cathedrals and monasteries in towns such as Bari, Trani and Otranto in the early eleventh century. For Bari we also know of the huge tenth-century palace of the catapan,

214

identified beneath the Norman church of S. Nicola, which incorporates sculptured material derived from the governor’s complex. Increased trading potential is documented in most Apulian ports by the appearance of merchants’ quarters, and in the countryside by the foundation of new farms and villages to produce grain, wine and olive oil for export; urban growth is further revealed by the need to build new, enlarged, circuit walls from the late tenth century. [5]

It is difficult to transfer this image of prosperity to the Longobard principalities in the west, where there was little scope for increased agricultural development around the various private castles. But a distinction can be made for castles within monastic lands. Detailed documentary investigation combined with archaeological field-work in Molise has helped reveal the complex pattern of landowning by the Benedictine monastery of S. Vincenzo in the Volturno valley and beyond. This monastery’s landed wealth grew from ducal, princely and royal gifts: in the eighth century over 500 sq. km were given by the Beneventan duke, consisting mainly of mountainous zones; grants and donations on variable scales continued into the eleventh and twelfth centuries, allowing for recovery of the site after its destruction by Arabs in 881. After 940 rights were awarded to build and exercise authority over castles and their tenants: such foundations often involved clearance of woodland to establish new arable zones, and rents were sometimes staggered to give communities time to settle in. This process of land colonization clearly helped in the economic rise of S. Vincenzo, which peaked in the late eleventh century. Excavations have begun to reveal the huge monastic structures of the day as well as the underlying eighth- and ninth-century complex (fig. 16); interestingly, traces of a late Roman villa were utilized in the

5. Burman, Emperor to Emperor, 102-3, 119-25.

215

Figure 16 Proposed architectural reconstruction of the plan of the abbey church of S. Vincenzo Maggiore, S. Vincenzo al Volturno, c.840 (Sheila Gibson; British School at Rome Archaeological Archive, 1993).

216

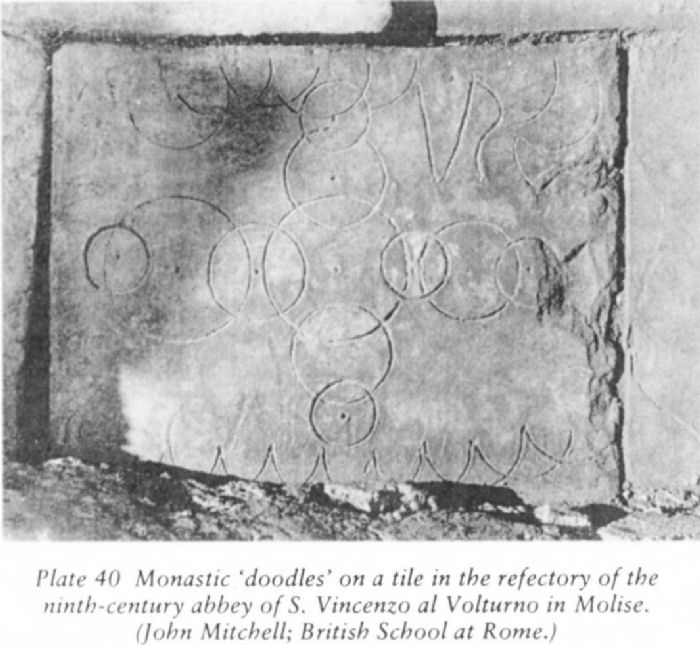

fabric of the early monastery, as happened in the monasteries at Farfa and Montecassino. The excavations have also yielded fascinating information on the internal production of pottery, glass and metal-work, indicating that S. Vincenzo acted as more than just a religious focus (pi. 40): as a large, centralized land-owning body it also acted as a magnet for industrial activity, providing a market for dependent communities and, undoubtedly, for centres beyond. Field survey in the Volturno and Biferno valleys has meanwhile reinforced the view that Roman farms and villages were generally abandoned in the fourth to sixth centuries and has shown an emergence of fortified hilltop sites from the ninth century, but there are minimal traces yet of settlement activity between these dates.

Plate 40 Monastic 'doodles’ on a tile in the refectory of the ninth-century abbey of S. Vincenzo al Volturno in Molise. (John Mitchell; British School at Rome.)

217

While excavations at S. Vincenzo verify an eighth-century foundation to the monastery, the contemporary peasant population remains somewhat elusive. [6]

Churches and monasteries were being erected in both towns and countryside throughout the ninth and tenth centuries, and many of these still survive in one form or another, complete with fragments of contemporary figured frescos, comparable to designs produced at S. Vincenzo. In the princely capitals of Benevento, Salerno and Capua elements of the ninth-century court chapels are visible (pl. 41); gastaldate centres such as Venosa and Teano present churches that overlie early Christian antecedents and are in turn overlain by Norman rebuildings; isolated churches include S. Pietro in Basento near Noci, and the tiny square chapel at Seppannibale. They are all fairly small and built in rough stone, and reveal an amalgam of styles, often based on late antique models, but combining Frankish and particularly Byzantine forms in terms of ornamentation. Graffiti, paintings and repairs are known for various of the characteristic cave churches such as Olevano, Prata and Monte Gargano, and scratched inscriptions at the latter record visits by various Beneventan notables extending from the seventh century into the 860s when the site was sacked by the Arabs; subsequent repairs show that the sanctuary remained a point of major pilgrimage. [7]

In these regions, too, not enough systematic archaeological study has occurred to allow us to comprehend

6.

· Hodges and Mitchell (eds), San Vincenzo al Volturno;

· articles by R. Hodges and C. Wickham in Francovich (ed.) Archeologia e storia del medioevo italiano;

· and R. Hodges (ed.), San Vincenzo al Volturno. The 1980-86 Excavations, Part I, Archaeological Monograph of the British School at Rome, VII (London, 1993).

7.

· M. Rotili, ‘La cultura artistica nel Ducato di Benevento’ in M. Brozzi, C. Calderini & C M. Rotili, L'Italia dei Longobardi (Milan, 1980), 75-85;

· C. D. Fonseca, ‘Longobardia minore e Longobardi nell’Italia meridionale’ in Magistra Barbaritas, 127-84.

218

Plate 41 The palace church of S. Sofia at Benevento, built between 760 and 780.

properly the character of Longobard and native settlement, particularly after the seventh century, when cemetery data grow scarce. Place-names and linguistic evidence broadly demonstrate zones of Longobard influence, but most artefactual data relate to the indigenous population, perhaps signifying fairly swift cultural fusion. One zone of interest lies between Lecce and Taranto in south-eastern Apulia, marked by the presence of toponyms recording the Limitone dei Greci and the Paretoni (the ‘big Greek frontier’ and the ‘big walls’) documented first in the eleventh century. These Paretoni, now surviving only in parts as massive banking up to 7 m wide and 3 m high, most probably formed the Byzantine defensive line against the Beneventan Longobard expansion into the heel of Italy from the later seventh century; place-names such as Sculca and Vigilia appear to pinpoint opposing Longobard positions to this border. Such a defence may have remained in use well

219

into the ninth century, but detailed investigation has yet to take place to determine the Limitene's form and longevity. [8] Likewise, almost nothing is known of the mechanics of Longobard border control elsewhere in the Beneventan territory, except for the presence of individual documented forts.

. . .