Житието на св. Вилибалд фон Айхщет (VIII в.) и исландските Leiðarvísir og borgarskipan (XII в.) и Heimslýsing (XIV в.) за Пелопонес. Тирас в библейски, скандинавски генеалогии на народите

Св. Вилибалд фон Айхщет (Saint Willibald), англосаксонец от южна Англия, е пътувал на поклонение в Ерусалим и Цариград през 723-729 г. Житието му, съставено още приживе, описва как той е плавал от Италия към Монемвазия (град в югоизточен Пелопонес) в "земята Славиния" (откъси А, Б и В по-долу).

Четири века по-късно Никулас Бергсон, игумен на бендектински манастир в северна Исландия (Nikulás Bergsson, † 1159), оставя пътепис на своето поклонение в Ерусалим през 1157 г. - Leiðarvísir og borgarskipan. Плавайки покрай о-в Кефалония и след това покрай Малеа, най-югоизточния нос на Пелопонес, Бергсон споменава за град "в България / Bolgaralandi".

Цялата фраза, "Þa er borg er Martini heitir, hon er á Bolgaralandi", бива превеждана както следва:

- "Then [there] is a town city called San Martino which is in Bulgaria [?]" (O. Pritsak, The origin of Rus’, 1981, откъс Г)

- два латински превода на Leiðarvísir дават:

"Tum in Bulgaria urbs martini." (E. Werlauff: Symbolae ad Geographiam Medii Aevi, Ex Monumentis Islandicis, Copenhagen, 1821, откъс Д)

и

"Tum urbs est, dicta Martini, sita in Bulgaria." (C. Rafn. Antiquités Russes d'apres les Monuments historiques des Islandais et des Anciens Scandinave, откъс Д)

- "Successively there is a city, called Martini, in the land of the Slavs" (L. Giampiccolo: Leiðarvísir, an Old Norse itinerarium: a proposal for a new partial translation and some notes about the place-names, 2013, откъс Е)

- K. Kålund, изследвайки генуезки портолани от XV в., отъждествява Martini с "Martin Carabo - удобно място за пускане на котва, намиращо се по средата между нос Малеа и град Монемвазия" (Kålund, Kristian. ‘En islandsk vejviser for pilgrimme fra 12. århundrede’, Aarbøger for nordisk oldkyndighed og historie, 3rd ser, 3: 1913, 51-105. <- недостъпна, цитирана от T. Marani).

- T. Marani отхвърля предположението на Kålund, посочвайки, че става дума за град (borg, urbs). Неговата интерпретация е:

‘the town which is called “Of Martin”. It is in the land of the Bulgarians’. Добавяйки: Bolgara-land does not refer to Bulgaria, but to the ‘land of the Slavs’ (T. Marani, Leiðarvísir. Its Genre and Sources, with Particular Reference to the Description of Rome, Durham theses, Durham University, 2012, откъс Ж)

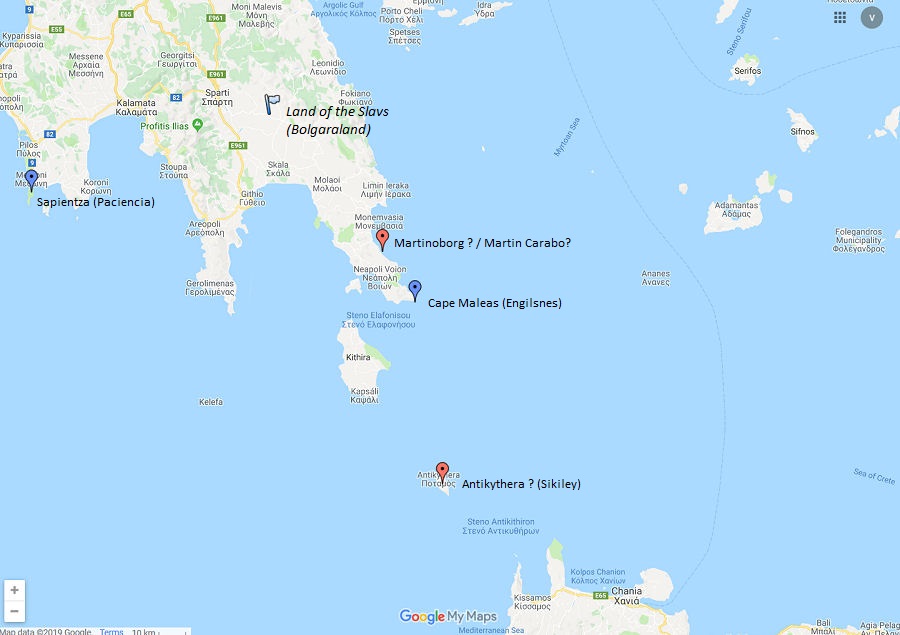

Marani също е съставил гугъл-карта с предполагаемия маршрут на Н. Бергсон от Дания до Ерусалим (карти 1, 2)

- Най-правдоподобна сред тези преводи изглежда интерпретацията на Joyce Hill (From Rome to Jerusalem: An Icelandic Itinerary of the Mid-Twelfth Century, The Harvard Theological Review, 1983, откъс И), че става дума за неназован (пристанищен) град в източен Пелопонес, с църква, посветена на Св. Мартин.

Hill също така добавя уговорката: "Bolgaraland: Not Bulgaria, but "land of the Slavs," who had long been settled in the Pelopennese".

От друга страна, в Heimslýsing ("Описание на света"), един вид продължение на Leiðarvísir, включено в "Книгата на Хаук" (Hauksbók, текст: https://heimskringla.no), една по-късна компилация от нач. на XIV в. в съответния пасаж се говори за "епископ Мартин": "... hia Tracia er Ungara land. þanan var Martinus byskup æskaðr. þar nest er Bolgara land. þat heitir gircland." (heimskringla.no: Heimslýsing_ok_helgifrœði). J. Þorkelsson (Nokkur blöð úr Hauksbók: og brot úr Guðmundarsögu, Reykjavik, 1865, стр. 12, бел. 90: archive.org) смята, че под Martinus byskup трябва да се разбира св. Мартин от Тур (316-397), което е малко вероятно.

За забелязване е как по-новите интерпретации и на Marani (2012), и на Giampiccolo (2013), и на Hill (1983) последователно преименуват "Bolgaralandi" на "земя на славяните". Т.е. почти всеки път, когато съвременните историци се сблъскват със средновековни свидетелства, свързващи, уеднаквяващи славяни с българи, те се чувстват задължени да се намесят. Независимо дали става дума за Климент Охридски и за "словенския"/"блъгарски език", или за българи/славяни на Алцек в Италия, или за българи/саклаби в Поволжието (ибн Фадлан) или за други географски райони: Алциок в Словения, "ванандските" българи в Армения, витинските славяни под водителството на (пра)българина Небул, а сега и "Bolgaralandi" в Пелопонес, всяко такова свидетелство се третира:

1. изолирано, само по себе си, и

2. като извънреден случай, като неестествен съюз и неестествено смесване на различни естества в объркания ум на средновековния повествовател, изискващо сега научни коментари и уточнения. А тези уточнения и "поправки" са в повечето случаи импотентни и слабо убедителни.

"Bolgaralandi" в източен Пелопонес през XII в. като "Българска земя" не би трябвало да бъде изненада. Хрониката на Монемвазия от X-XI в., например, според която аварите завладяли Пелопонес и го владеели в течение на 218 години, пише за същите авари как „аварите били по род хунски и български народ” (Γένος οἱ Ἀβάρες ἔθνος Οὐνικὸν καὶ Βουλγαρικὸν).

Макар и без пряко отношение към Италия, свидетелствата на Вилибалд и на Бергсон са включени тук, в директорията за Италия, тъй като те говорят за едно малко неочаквано "място за среща", за една българска връзка по море с Италия и с западните пилигрими.

Тирас в библейски, скандинавски генеалогии на народите

Съгласно Библията (Генезис (10, 2) и 1. Хроника (1, 5)) Тирас, най-младият син на Яфет и най-младият внук на Ной е родоначалник на траките. В други традиции Тирас е родоначалник на други народи: на персите в Талмуда, на Ашкеназ и Тогарма според ранни арменски историци, и т.н. (По-подробно изложение: на en.wikipedia.org/Tiras.) Европа, обаче, следва библейската традиция и така "Тирас, от който са траките" бива включен в Етимологията на Исидор Севилски (556-636), особено популярна книга в Средните векове.

Наличието на Славиния/"Българска земя" в Пелопонес между VIII и XII в., покрай вековния маршрут на западните пилигрими, и встрани, независимо от Цариград, между другото, трябва да обясни, например, и някои особеностите в исландски библейските списъци на народите. О. Прицак е пак човекът, обърнал внимание на това. Той съпоставя пасажите за потомците на Яфет в исландските Landafrœði и Heimslýsing с източника им, Етимологията на Исидор (Pritsak, The origin of Rus’, 1981, Откъс Й):

1) Etymologiae (9.2.31) на Исидор (VII в., www.thelatinlibrary.com):

Filii igitur Iaphet septem nominantur: . . . Thiras, ex quo Thraces; quorum non satis inmutatum vocabulum est, quasi Tiraces. (англ. ...)

(Превод от The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Tr. by S. Barney et al., 2006): Now the tribes of the sons of Japheth. 26. Seven sons of Japheth are named: . . . 31. Tiras, from whom the Thracians; their name is not much altered, as if it were Tiracians.

2) Landafrœði (XII в.):

Iapheth atti VII syni; þeira nófn voro þessi: Gomer, Magoc, Madai, Iuban, Tubal, Masok, Tirak. Þessi ero þjodlónd i þeim hluta heims, er Eyropa heiter: . . . Bolgara-land, þar var Tirac. Un[g]araland, Saxland, Frakland, Spanland, þar var Tubal.

(Превод на Прицак): Japheth had seven sons; their names are these: Gomer, Magoc (Magog), Madai, Iuban (Javan), Tubal, Masok (Masoch), Tirak (Tiras). THese are the empires in their allotment of the world which is called Europe: . . . Tirac (Tiras) ['s allotment] was in Bolgaraland (Bulgaria). Hungary, Saxony, Frakland (Francia), Spanland (Spain) Tubal ruled.

3) Heimslýsing (XIV в.):

Iafeth Noa sonr atte VII. sono; þessi ero nofn þeira: Gomer, Magon, Madia, Ioban, Tubal, Mosok, Tiras. þessi ero þar þioðlond: Tiras Bolgara lande oc Vngara lande, Saxlande oc Fraclande. Tubal Spanía l[ande] oc Rumueria lande Suiþioð oc Danmorc oc Noregí.

(Превод на Прицак): Japhet Noahsson had seven sons; these are their names: Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech, Tiras. These are the empires [located] there: . . . Tiras [ruled in] Bulgaria and Vngaraland (Hungary), Saxland (Saxony) and Tracland (Francia). Tubal [ruled in] Spain and Rumverialand (the land of the Romans), Sweden and Denmark and Norway.

Така Тирас, "от който произлизат траките" в Исидоровия пасаж (т.е. в Библията, Генезис (10, 2) и 1. Хроника (1, 5)) става "Тирас, владетел на България", "Тирас, владетел на България и Унгария, Саксония и Тракия" в исландските генеалогии. Исландските различия от класическата библейска версия вероятно се дължат на информатори-българи, на контакти на исландските пилигрими до светите места с българи от Балканите, вероятно точно в Пелопонес.

Предполагаемият маршрут на Н. Бергсон от Дания до Ерусалим (от T. Marani):

Откъси:

А. Hugeburc's Life of St. Willibald - Extracts (Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 1977)

Б. The hodæporicon of Saint Willibald (ca 754 AD) by Roswida (Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society, 1891)

В. Житие Виллибальда, епископа Эйхштеттского (Свод древнейших письменных известий о славянах. Том II (VII–IX вв.), Москва, 1995)

Г. Nikulás Bergsson’s Leiðar-vísir (Omeljan Pritsak. The origin of Rus’. v. I. Old Scandinavian Sources other than the Sagas)

Д. Латински преводи на Leiðar-vísir : Carl Rafn. Antiquités Russes d'apres les Monuments historiques des Islandais et des Anciens Scandinave, Copenhague, 1852, и Ericus Werlauff: Symbolae ad Geographiam Medii Aevi, Ex Monumentis Islandicis, Copenhagen, 1821.

Е. Luana Giampiccolo: Leiðarvísir, an Old Norse itinerarium: a proposal for a new partial translation and some notes about the place-names (Nordicum – Mediterraneum, 8 (1) 2013)

Ж. Tommaso Marani, Leiðarvísir. Its Genre and Sources, with Particular Reference to the Description of Rome (Durham theses, Durham University, 2012)

И. Joyce Hill, From Rome to Jerusalem: An Icelandic Itinerary of the Mid-Twelfth Century (The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 76, No. 2 (Apr., 1983), pp. 175-203)

Й. A Biblical Genealogy of Nations (Omeljan Pritsak. The origin of Rus’. v. I. Old Scandinavian Sources other than the Sagas)

Hugeburc's Life of St. Willibald - Extracts [1]

John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades, Aris & Phillips, Warminster 1977, p. 125-126:

(Извадка в .pdf формат, от www.scribd.com)

Chapter 8 - A.D. 720

Chapter 9 - A.D. 720-3

Chapter 10A - A.D. 723

Chapter 10B

. . .

1. Hugeburc’s was the first Life of Willibald: There are also three other Lives written in the 9th-10th, the 11th, and the fourteenth century. The extracts given here are an attempt to provide the substance of what Willibald dictated to Hugeburc, and wherever possible interpolations and florid phrases have been omitted.

![]()

126

Chapter 11 - A.D. 723-4

They sailed on and crossed the Adriatic Sea, reaching the city of Monembasia in the country of Slavinia. They sailed on to the island of Cheos, left Corinth to port and from there went to Samos. Then they sailed to Asia, to the city of Ephesus, which is a mile from the sea. From this they walked to the place where the Seven Sleepers lie buried, and then on to St. John the Evangelist at a beautiful spot outside Ephesus. From there they walked to a large village called Phygela, two miles from the sea. They stayed a day there, begged some bread, and went to a spring in the middle of the village. There they had their meal, sitting at the edge of the spring and dipping their bread in the water. They went walking on, and came to the city of Strobolis [12] on a high mountain beside the sea, and from that they reached a place called Patara, in which they stayed until. . . winter was over. After that, sailing on, they came to a city called Miletus, which had once almost been submerged by water. There were two solitaries there, living on pillars. It was strongly protected with a very high big stone wall to prevent the water doing any damage. From there they crossed to Mount Gallianorum, [13] but every single inhabitant had gone away. They went hungry there ... and were afraid their time had come to die. But the Almighty ... provided food for his poor.

Sailing on from there they came to the island of Cyprus, which lies between the lands of the Greeks and the Saracens. They arrived at the city of Paphos, where they stayed for three weeks of Easter-tide (a year had now gone by). [14] From there they went to the city of Constantia, where St. Epiphanius lies buried, and stayed there until after the Nativity of St. John the Baptist. [15]

12. Strobolis was between Myndos and Halicarnassus: Bauch, p. 92, n. 63.

13. See Bauch p. 93, n. 67.

14. Since leaving Rome. Easter Day 724 fell on 16 April.

15. 24 June 724. Willibald now enters the Muslim empire under its new Caliph Hisham, who reigned from 28 January 724 to 6 February 743.

Откъс Б.

The hodæporicon of Saint Willibald (ca 754 AD) by Roswida

From: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society (1891)

(интернет-версия на sourcebooks.fordham.edu/../willibald.asp)

. . .

Thence they sailed for Syracuse, a city in the same country. Sailing from Syracuse, they crossed the Adriatic and reached the city of Monembasia, [2] in the land of Slavinia, and from there they sailed to Chios, leaving Corinth on the port side. Sailing on from there, they passed Samos and sped on towards Asia, to the city of Ephesus, which stands about a mile from the sea. Then they went on foot to the spot where the Seven Sleepers lie at rest. [3] From there they walked to the tomb of St. John, the Evangelist, which is situated in a beautiful spot near Ephesus, and thence two miles farther on along the sea coast to a great city called Phygela, where they stayed a day. At this place they begged some bread and went to a fountain in the middle of the city, and, sitting on the edge of it, they dipped their bread in the water and so ate. They pursued their journey on foot along the sea shore to the town of Hierapolis, which stands on a high mountain; and thence they went to a place called Patara, where they remained until the bitter and icy winter had passed. . . .

[2] Monembasia is a small town near the south of Morea. The Slavonic Bulgarians were allpowerful at Constantinople, where they had placed Leo III on the imperial throne. It is not surprising, then, that Morea should have been occupied by them.

[Halsall note: Talbot seems to overlook widespread Slavic settlement in the Morea -- i.e. the Peloponnese -- at this period.]

Откъс В.

Житие Виллибальда, епископа Эйхштеттского (В.К. Ронин)

От: Свод древнейших письменных известий о славянах. Том II (VII–IX вв.). Составители С.А. Иванов, Г.Г. Литаврин, В.К. Ронин. Отв. редактор Г.Г. Литаврин. Москва 1995, с. 439-441:

(Целия том в .djvu формат, 13.6 Мб)

Житие Виллибальда, епископа Эйхштеттского

§ 1. Англосакс Виллибальд [Не следует путать его с майнцским священником Виллибальдом, автором «Жития св. Бонифация»] (ок. 700—786) был монахом в Западной Англии, в 721 г. отправился паломником в Рим, а в 723—729 гг. совершил паломничество в Палестину и Константинополь. Вернувшись в Италию, он до 738 г. жил в бенедиктинском монастыре в Монте-Кассино, затем стал сподвижником св. Бонифация в его миссионерской и церковно-организаторской деятельности в Германии, где в 741 г. был посвящен Бонифацием в епископы в Эйхштетте на р. Альтмюль в Баварии.

§ 2. Как явствует из его «Жития», оно было составлено в последние годы его жизни некоей монахиней англосаксонского происхождения, его дальней родственницей, в Хейденхеймском монастыре близ Эйхштетта. Она же написала затем, и «Житие Виннебальда», основателя монастыря, брата Виллибальда. Источником ее первого сочинения послужил, как указано в тексте, рассказ самого епископа Виллибальда, который она слышала 23 июня 778 г. и, судя по ее словам, тогда же записала, так что в одном месте осталась неизменной даже форма рассказа от первого лица (Vita Willibaldi 4, с. 96: «и пастухи давали нам пить горькое молоко»). Итак, повествование Виллибальда о его паломничестве в Святую Землю, в частности о его проезде через «землю Славинию» на Пелопоннесе (Греция), может быть датировано с необыкновенной для раннесредневековых текстов точностью и передано, несомненно, достоверно, хотя, впрочем, сам рассказ отстоит от описываемых событий более чем на полвека. Это — самое раннее конкретное упоминание о заселенной славянами области Пелопоннеса.

Изложение просто и безыскусно, хотя заметно пристрастие монахини к греческим и иным редким словам. В то же время язык ее — варварский, изобилует самыми элементарными грамматическими ошибками и германизмами.

§ 3. «Житие» сохранилось в девяти списках. Древнейшая и лучшая рукопись — Мюнхенская конца VIII или начала IX в. (cod. Monacensis Latinus 1086) (подробнее о рукописях см.: Vita Willibaldi, 82—84).

Текст приводится по изданию О. Хольдер-Эггера 1887 г. (Vita Willibaldi 4, 93). Учтены также немецкий перевод Х. Хана (Hahn. Die Reise, 17—25) и английский Т. Райта (Wright. Early travels, 13—22).

439

![]()

... Et inde navigantes, venerunt ultra mare Adria ad urbem Manafasiam in Slawinia terrae; et inde navigantes in insulam nomine Choo, et demittebant Chorintheos in sinistra parte...

(Побывав в Сицилии, Виллибальд с двумя спутниками отплыл из Сиракуз.)

И плывя оттуда [1], они прибыли через Адриатическое море к городу Манафасия [2] в земле Славинии [3], и, плывя оттуда, — на остров Хоо [4], и оставили Коринф с левой стороны.

(Далее они отправились на остров Самос и в Эфес.)

КОММЕНТАРИЙ

1. Эту часть пути Виллибальд и его спутники проделали летом 723 г.

2. Имеется в виду Монемвасия, византийский город на юго-восточном побережье Пелопоннеса, важный порт и епископский центр. Согласно византийской «Монемвасийской хронике» (середина X в.), город был основан в неприступной местности у моря в 582 или 583 г. обитателями Лакедемона, опасавшимися вторжения славян и аваров с Балканского полуострова (Chron. Mon. 117—125, с. 14). См. наст. изд., с. 340.

3. Как явствует из той же «Монемвасийской хроники», славяне («авары») овладели Пелопоннесом в 587—588 гг. и господствовали, никому не подчиняясь, там 218 лет (Chron. Mon. 135—138, с. 16—17. Cp.: Koder. Zur Frage). Ряд греческих историков относят утверждение славян на Пелопоннесе только к последней трети VII в. (Malingoudis. Studien, 18—19). Термин Slawinia необычен для латинской традиции VII—VIII вв., но зато был распространен в Византии, где его, по-видимому, и услышал Виллибальд. Славиниями (Σκλαβηνία, Σκλαβηνίαι) византийские авторы, начиная с Феофилакта Симокатгы (VII в.), но особенно часто в IX—X вв., называли более или менее крупные территориальные общности славян, обладавшие самостоятельной политической организацией (см.: Литаврин. Славинии. Ср. наст. изд., с. 311, коммент. 259). Именно так можно понять и слова Slawinia terrae в рассказе Виллибальда.

4. Наиболее убедительная идентификация — Кеос (ныне Кея), самый северный из Кикладских островов Эгейского моря (Hahn. Die Reise, 17, Anm. 59; Vita Willibaldi 93, n. 6).

Nikulás Bergsson’s Leiðar-vísir

Omeljan Pritsak. The origin of Rus’. vol. I. Old Scandinavian Sources other than the Sagas, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1981, стр. 704-715:

(Извадка в .pdf формат)

APPENDIX FOUR. The Texts of the Icelandic Itinerary Literature

Nikulás Bergsson’s Leiðar-vísir

Nikulás Bergsson’s Leiðar-vísir is embedded in a geographic miscellany called Landafræði and has been preserved in two vellum manuscripts: AM 194,8° fols. 11-16 (written in west Iceland in 1387) and AM 736 II, 4°, fol. 1 r.v. (written about 1400). The text has been published twice: in E. C. Werlauff's Symbolae (Kbh, 1821), text and Latin translation, pp. 9-32; commentary, pp. 32-54; and by Kristian Kålund in his critical edition of the Icelandic encyclopedic text, Alfræði Íslenzk: Islandsk encyclopcedisk litteratur. I. Cod. Mbr. AM 194, 8vo (Kbh, 1908) (SUGNL XXXVII) Introduction, pp. xix-xxv and ; text, pp. 12-31.

The entire translation of the text has also been published twice, in Latin by E. C. Werlauff, Symbolae (Kbh, 1821), pp. 32-54, and in Danish by Kr. Kålund in ÅNO 3rd ser., vol. 3 (Kbh, 1913), pp. 52-61. A partial Latin translation appeared in AR II, pp. 405-415; Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. translated into English and commented on the greater part of the text (the route from Iceland to Rome, including a description of the eternal city) in four meticulous articles: Mediaeval Studies 6 (1944), pp. 314-354; Scandinavian Studies 17; (1943), pp. 167-173; JEGP 42 (1943), pp. 210-218; The Harvard Theological Review 33 (1940), pp. 267-289. The special literature is: Paul Riant, Les Scandinaves en Terre Sainte (Paris, 1865), pp. 80-90;

704

![]()

![]()

705

Finnur Jonsson and Ellen Jørgensen, ÅNO 1923 (Kbh, 1924), 1-36 pp. and Mémoires de la Société Royale des Antiquaires du nord 1920-1925 (Kbh, 1925), pp. 49-87 + 1 facs.; Sigfus Blöndal, Nordisk Tidskrift (Letterstedts) (1940), pp. 316-327; and Skírnir 123 (Rvík, 1949), pp. 67-97.

The text given is that of the Leiðarvísir after the standard edition of Kålund; added are Magoun’s emendations, and that part translated by Magoun with some changes and additions; the final part of the text was translated by me.

|

. . . Úr Noregi er fyrst a[t] fara til Danmerkri Ála-borg. Sva telia Romferlar, ath or Ála-borg se II dag[a] [fór] til Vebiarga. Þa er viku fór til Sles-vikr. . . . |

. . . From Norway [1] the first stage is to travel to Aalborg in Denmark. Pilgrims to Rome report that from Aalborg it is a two days’ journey to Viborg. Then it is a week’s journey to Schleswig. . . . |

![]()

714

|

... [Þ]a er [Ga]ida.

Þa er II daga for til Kapu.

Þa ferr til Beneventar.

[Ut fra er] Manupl.

Þa Brandeis.

I hafs-botn þadan ero Fe[neyiar], [þar er] [p]atriarcha stoll.

Þar ero helgir domar Marcus ok Lukas.

Ska[mt fra] [D]uracur cr Mario-hofn. |

... Then [there] is Gaeta.

Then it is two days’ journey to Capua.

Then one day to Benevento.

Next to Monopoli.

Then Brindisi.

In a gulf, after that there is Venice. There is a patriarch’s throne there.

There are preserved relics of [SS.] Mark and Luke.

Not far from Durazzo is Santa Maria del Kassopo [on Corfu]. |

![]()

715

|

Þa er Visgardz-hófn.

Þa er Eng[ils-n]es.

Þa er skamt til eyiar Paciencia eda Sikileyiar,

[Þar] er iardelldr ok votn vellandi sem á Islandi.

Þa er borg, er Martini heitir, hon er aa Bolgara-landi.

Þa er at sigla til eyiar, er Ku heitir, þar koma leidir saman af Puli ok af Miklagardi.

Verdr til land-nordrs á Pul, en ut i haf til Kritar.

Ut fra Ku er ey, er Roda heitir.

Þa er ath sigla yfir til til (sic!) Griklandz ok til Rauda-kastala. . . . |

Then [there] is Porto Guiscardo [on Cephalonia],

Then [there] is Cape Malea (= Cap S. Angelo on Morea).

Not far from that is the island of Sapiéntza or Sicily [belonging to the Kingdom of Sicily?],

where there are — as in Iceland — volcanic fires and boiling waters. [21]

Then [there] is a town city called San Martino which is in Bulgaria [?].

Then one sails to the island called Chios, a junction of the routes to Puglia (Apulia) and Constantinople.

In the northwest direction one reaches Apulia, and at the end of the sea [the island of] Crete.

Beyond Chios there is an island called Rhodes.

Then one sails over to Greece or to Kastelloryzon. . . . |

21. This observation of Nikulás deserves attention, since it was made in the pre-secular age.

Латински преводи на Leiðar-vísir

1. Carl Christian Rafn. Antiquités Russes d'apres les Monuments historiques des Islandais et des Anciens Scandinave, Copenhague, 1852, стр. 407:

Tum urbs est, dicta Martini, sita in Bulgaria.

2. Ericus Christianus Werlauff, Symbolae ad Geographiam Medii Aevi, Ex Monumentis Islandicis, Copenhagen, 1821, стр. 27:

(.pdf файл на www.septentrionalia.net)

Tum in Bulgaria urbs martini. [145]

145. De hacce Martinopoli nil mihi constat.

Откъс Е.

Luana Giampiccolo, Leiðarvísir, an Old Norse itinerarium: a proposal for a new partial translation and some notes about the place-names, Nordicum – Mediterraneum, 8 (1) 2013:

(.pdf файл на www.skemman.is)

Not far from Durazzo there is Saint Mary of Kassiopi. Then there is Port Guiscard. Then there is Cape Malea. Following, there is a short distance to the island of Sapientza or Sikiley; in this place there are volcanoes and hot water as in Iceland. Successively there is a city, called Martini, in the land of the Slavs. Then one has to sail to an island, called Kos, where the routes from Apulia and from Constantinople merge, this island is to the north of Apulia and by sea you go to Crete. Off the coast of Kos there is an island called Rhodes. Then it is necessary to navigate to Greece and to Kastellorizon.

Tomasso Marani, Leiðarvísir. Its Genre and Sources, with Particular Reference to the Description of Rome, Durham theses, Durham University, 2012, стр. 36:

(.pdf файл на etheses.dur.ac.uk)

стр. 36:

The identification of the next stop is also problematic. Leiðarvísir adds that after sikileyiar there is borg er martini heitirhon er aa bolgara landi, ‘the town which is called “Of Martin”. It is in the land of the Bulgarians’ (ll. 125-26). Bolgara-land does not refer to Bulgaria, but to the ‘land of the Slavs’, who had been for a long time in the Peloponnese after their conversion to Christianity in the ninth century (Hill 1983: 186). The ‘Town of Martin’ cannot be identified with any certainty. Kålund (1913: 82) found in a fifteenth-century Italian portolan (Kretschmer 1909: 510, 536) a reference to Martin Carabo, a good anchorage halfway between Cape Maleas and Monemvasia. Kålund’s interpretation remains, however, questionable, since Leiðarvísir clearly refers to a town and not simply to a good landing-place for ships.

Откъс И.

Joyce Hill, From Rome to Jerusalem: An Icelandic Itinerary of the Mid-Twelfth Century, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 76, No. 2 (Apr., 1983), pp. 175-203.

(.pdf файл от www.jstor.org)

стр. 186:

Nikulas is thus seen to be naming two separate islands, neither of which he believes to be far from Engilsnes. Sikiley is the normal Old Icelandic name for Sicily, but Sicily is a long way from Engilsnes and one would not expect a reference to it here unless there was a confusion in the transmitted text or in Nikulas' own memory about what he had seen or been told. In his Danish com- mentary (pp. 81-82), Kalund proposed that Sikiley here is Nikulas' attempt to represent Sicillo in Icelandic, the Venetian name for the small island of Cerigo, which is near Engilsnes. Perhaps the similarity of name and Nikulas' confusion of them when he attempted to represent Sicillo in Icelandic led him, on his return home, to attribute the geology of Sicily (Sikiley) to the island of Sicillo (Sikiley), which he correctly remembered as being near Engilsnes. Alternatively the fault may lie with a later scribe, who mistook a bald, but correct, reference to Sikiley (Sicillo) near Engilsnes as a reference to the much more familiar Sikiley (Sicily) and himself added the details about volcanic activity. Nikulas does not claim to have visited either Paciencia or Sikiley (he refers to a number of places off his route throughout the itinerary) and he certainly did not visit or sail past Sicily in either direction. [29]

41

"Of Martin" (borg, er Martini heitir): A town that Nikulas presumably visited after rounding Engilsnes, hence on the east coast of the promontory. The name implies that there was a church dedicated to St. Martin, but not necessarily that the town was named after the saint. [30] I have not been able to discover exactly which town he means. [31] Kalund, in his Danish commentary (p. 82), refers to a late fifteenth-century incunabulum in which the name Martin Carabo is given to a good anchorage on the promontory's east coast, where ships could catch favorable winds for continuing through the Greek islands.

42

Bolgaraland: Not Bulgaria, but "land of the Slavs," who had long been settled in the Pelopennese. [32] They had been converted to Christianity following their subjugation by Michael III in the ninth century.

29. The mistaken assumption that Nikulas visited Sicily is made by Turville-Petre, Origins of Icelandic Literature, 160.

30. As in the case of Bolsena, earlier in the itinerary, which, in the Icelandic text (Kalund, Alfracdi Islenzk, 17) is called "Kristinaborg" after its saint. See Magoun, "Pilgrim Diary," 345.

31. Riant, (Scandinaves en Terre Sainte, 85) called the town San Martino de Laconie, but without explanation.

32. Willibald, en route for Jerusalem in the early eighth century, likewise traveled via this easternmost promontory and called the country "Slavinia" (Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 126)

Откъс Й.

A Biblical Genealogy of Nations

Omeljan Pritsak. The origin of Rus’. vol. I. Old Scandinavian Sources other than the Sagas, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1981, стр. 520-527:

(Извадка в .pdf формат)

. . .

[да се включи]