![]()

Carnegie Endowment for International peace

Report ... to inquire into the causes and Conduct of

the Balkan Wars

CHAPTER III

Bulgarians, Turks

and Servians

1. Adrianople

The Commission was afforded a perfectly natural opportunity of investigating

the atrocities attributed to the Bulgarians after they had taken Adrianople.

On August 20, 1913, the Dally Telegraph published a very solid body

of material sent to the paper by Mr. Ashmead Bartlett, and printed under

the suggestive heading "Terrible Reports by a Russian Official." On August

26 and 27, this same report appeared in Constantinople in the official

organ of the Committee of Union and Progress, Le Jeune Turc. Since,

however, the latter contained details omitted by the Daily Telegraph,

the information published in Le Jeune Turc was evidently first hand.

On August 28 Le Jeune Turc revealed the source of its information

as the result of an unofficial Russian contradiction inserted in La

Turquie of August 27. "We are authorized," declared the unofficial

organ of the Russian Embassy at Constantinople, "to give a categorical

denial of the information of the Daily Telegraph reproduced in Le

Jeune Turc and attributed to a Russian official. No Russian official

has been commissioned to make inquiries in Thrace and at Adrianople, or

to obtain any kind of information : none is therefore in a position to

supply such a report. Nor have the Russian consuls recorded the facts mentioned

in the Telegraph." Replying to this denial, which certainly emanated

from the Russian Embassy, Le Jeune Turc stated that "the document

in question was not the work of a Russian official in active service, but

of an ex-official, the Consul-General Machkov, who was in fact the correspondent

of the Noroie Vremya." It should be added that Mr. Machkov's telegraphic

"report" was rejected by his paper, and that, according to the statement

of Mr. Machkov's colleagues of the Constantinople press, the expense of

his telegram amounting to ?T150, was repaid him by the Committee. Le

Jeune Turc itself said: "Fearing, no doubt, lest the paper (the Novoie

Vremya) being excessively Bulgarophil [This is not at all the case.]

might not publish the results of his eight days' inquiry in Adrianople,

Mr. Machkov sent copies of it to the President of the Council of Ministers

and the Foreign Minister."

The veracity of the document, which made a profound impression in Europe, is naturally in no way prejudiced by its origin and history, which do however assist an understanding of the spirit in which it is conceived. One of the members of the Balkan Commission came to Adrianople to follow up Mr. Machkov's information. He succeeded in getting in touch with the sources from

110 ![]()

which it was largely derived, and had repeated to him verbally practically the whole of the facts and sayings contained in Mr. Machkov's account. The truth seems to be that while Mr. Machkov invented nothing and added practically nothing to the information he was able to collect in Adrianople, he did rely upon distinctly partisan sources, in so far as the medium through which his information came was Greek. The member of the Commission was at pains not to confine his inquiry to this medium. In addition to obtaining from the persons responsible for the administration of the city in occupation, a long series of official Bulgarian depositions (see Appendix G, 3), he succeeded in pushing his inquiries in Adrianople itself, in other than purely Greek areas, and in utilizing the depositions of Turkish prisoners at Sofia, collected by another member of the Commission (see Appendix G, 2). Thus without any intention of rehabilitating the Bulgarians, he succeeded in establishing the facts in a more impartial manner than could be done by Mr. Machkov, who had been known as a very pronounced Bulgarphobe since his tenure of the Russian consulate at Uskub, fifteen years previously.

The account of affairs in Adrianople falls into three sections: first, the capture of the town and the days immediately following,—March 26-30, 1913; secondly, the Bulgarian administration of the town during the occupation, and thirdly, the last days and the evacuation,—July 19-22, 1913.

THE CAPTURE OF THE TOWN

The particular charge made against the Bulgarians during this short period is that they were guilty of acts of cruelty against the Turkish prisoners and of pillaging the inhabitants of the town. Any clear establishment of their responsibility depends on a knowledge of the situation existing prior to the occupation. To throw light on this point we will refer to a document entitled Journal of the Siege of Adrianople, published in Adrianople itself over the initials "P. C.," belonging to a person well known in the locality and worthy of every confidence. So early as January 31 (new style), P. C. remarks that "the famine has become more atrocious: there is nothing to be heard in some of the poor quarters of the town but the cries of the little children asking for bread and the wailing of the mothers who have none to give them. From the Hildyrym quarter it is reported that a man has committed suicide after killing his wife and three children. A Turkish woman, a widow, is said to have cast her little ones into the Toundja. * * *" And so on. On February 12, P. C. speaks of the "famished soldiers," forbidden to receive alms, and who "beg you to cast your money on the ground, whence they may pick it up an instant after." On March 2, revolt broke out among the Hildyrym populace and the writer forecasts what was to follow in these words: "A day of vengeance and reprisals will come when the besiegers enter." The soldiery stole bread in broad daylight and refused to give it up when taken in the act. P. C. describes, two days

111 ![]()

after, how "groups of people pass you who can hardly hold each other up; most of their faces are emaciated, their skin looks earthy and corpse-like; others with swollen limbs and puffy countenances seem hardly able to stumble along. You see them chewing at lumps of snow to cheat their hunger." And nearly two weeks were still to pass before the surrender! On March 12 the following scene took place: "A soldier crossing the Maritza bridge suddenly stopped, beat the air two or three times with his hands and fell down dead." He was thought to be wounded but "it was only starvation." "Stretchers bearing dead or diseased persons pass in constant succession; the doctors predict an appalling mortality as soon as the mild weather comes." On March 19, "In the hospitals one death follows another; yesterday two new cases of cholera were reported." * * * "This morning a poor trooper was brought in, poisoned from browsing on grass. Since the spring the cases have been multiplied." On March 22, "We have had five deaths last night; at the moment the mortality is from 50 to 60 a day, the result not of any epidemic, but of pneumonia affections and physiological starvation. Many have eaten unwholesome or poisonous bodies." Finally, there is the extract referring to the "last day of Adrianople," i. e., Wednesday, March 26, the day on which the town fell. It runs as follows:

The streets and squares are gradually filling with emaciated and ragged soldiers, who march gloomily to the rendezvous or sit down with an air of resignation at the corners and along the walls. There is no disorder among them: on the contrary they present a picture of utter prostration and sadness. * * *In contrast to the calm dignity of the Turks, the Greek mob showed an ever increasing meanness. They did not yet dare to insult their disarmed masters, but began to pillage like madmen, to an accompaniment of yells, blows and blasphemies. The Turks let them carry off everything without saying a word. [These somewhat long quotations from P. C.'s book have been made because it is now a bibliographical rarity. P. C.'s impressions are confirmed by another Journal of the Siege of Adrianople, by Gustave Cirilli (Paris: Chapelot, 1913), see pp. 129-151, etc.]

It only remains now to place the picture thus given in juxtaposition with Mr. Machkov's report and the commentary by the Bulgarian authorities on the events at the moment of the entry of their troops, to see how the different accounts complete and confirm one another.

Take, to begin with, the truly awful fate of the prisoners incarcerated in the island of Toundja, Sarai Eski. A member of the Commission visited the island. He saw how the bark had been torn off the trees, as high as a man could reach, by the starving prisoners. He even met on the spot an aged Turk who had spent a week there, and said he had himself eaten the bark. A little Turkish boy who looked after the cattle on the island, said that from across the river he had seen the prisoners eating the grass and made a gesture to show the inquirer how they did it. General Vasov stated in his deposition (see Ap-

112 ![]()

Fig. 14.—Isle of Toundja

Trees stripped of

bark which the prisoners ate

pendix G, 3) that he gave the prisoners permission to strip the bark off the trees for fuel, a fact confirmed by other trustworthy witnesses. The same general, from the second day on, ordered a quarter loaf to be distributed to the prisoners, which he took from the rations of the Bulgarian soldiery. This was confirmed by Major Mitov, who was entrusted with carrying out the order, which is moreover inscribed in the War Minister's archives (see Appendix G, 5). On the first day the victorious soldiery shared their bread with the prisoners and the starving populace. But touching incidents like this could not, any more than the general's order, supply the mass of the people with the food for lack of which they perished, and there are good grounds for believing that these poor wretches went on consuming the "unwholesome or poisonous" stuffs of which P. C. speaks.The mortality among the prisoners must have been severe, especially in the island, where cholera broke out again on the third or fourth day of the siege. There is evidence of a want of tents, which was indeed true of the whole army. The further fact that these unfortunate creatures passed the night exposed to all the rigors of rain and freezing mud, would in itself explain the increasing mortality. It is hardly possible to believe, after reading the descriptions published in the European press, for example Barzini's article in the Corriere delle Sera, that the isolation of the sick really had the good effects alleged by General Vasov.

The number of deaths has been variously estimated. Major Mitov speaks of thirty after the first morning. Major Choukri-bey, a captive officer, puts the number in a single day at a hundred; General Vasov estimated the total number of deaths at 100 or 200. The real figures must be higher. The Turk interrogated by the member of the Commission told him that the group in which he was consisted of some 1,800 persons confined in a narrow space indicated by

113 ![]()

a gesture. On the night of March 15, 187 of them, he said, died of cold and hunger. The witnesses, it may be noted, put disease second or third among the causes of death. The main cause was still, as during the siege, weakness and exhaustion resulting from starvation, the agonizing effects of which lasted not only during the five days of the final struggle of which Mr. Vasov speaks, but for months. It must certainly not be forgotten that the explosion of the bridge over the Arda, and the destruction of the Turkish depots, made it difficult to provide food for 55,000 prisoners and inhabitants. But when all these admissions have been made, there remains as a fact not to be denied, the cruel indifference in general to the lot of the prisoners. This fact is fully confirmed by the depositions of the captive Turkish officers at Sofia. One is therefore bound to admit that the conduct of the victors towards their captive foes left much to be desired. Some of the rigorous measures reported by Turkish officers might be given as a reason against the attempts to escape made by certain prisoners. But that can not explain everything: what about the vanquished who were bayoneted at night and their corpses left exposed in the streets till noon? The case reported by Mr. Machkov, of the Turkish captive officer who, being too weak to march, was slain by the Bulgarian soldiers in charge, as well as a Jew who had tried to defend him, is fully confirmed by a reserve officer, Hadji Ali, himself a prisoner at Sofia. Mr. Machkov gives the name of the compassionate Jew, Salomon Behmi; and at Constantinople the very words uttered, in Turkish, by this Jew, "Yazyk, wourma" ("It is a sin: do not kill,") were reported to the member of the Commission. Hadji Ali knew the name of the slain Turk, Captain Ismail-Youzbachi, and saw him fall with his own eyes. The explanation given by General Vasov and the Baroness Yxcoull proves that the death of the thirteen Turks slain in the mosque at Miri-Miran can not be laid at the Bulgarians' door; but the depositions of the Turkish soldiers concerning the murder of the sick and diseased prisoners on the Mustapha Pasha route are more than probably true. We shall return to this question of the treatment of prisoners in the chapter dealing with international law.

A Greek version of the pillage of Adrianople reproduced by Mr. Machkov is unkind to a degree calculated to prejudice public opinion. Apart from Mr. Machkov and Mr. Pierre Loti, who merely repeats the Turkish version prevailing at the moment without verifying it, almost all the authorities agree in recognizing- that the pillaging during the days that followed the fall of the town was due to the Greeks themselves—to some extent also to the Jews, and Armenians; but mainly to the Greeks,—who simply fell upon the undefended property of the Turks. The quotations made above from P. C.'s journal foreshadow this truth, which is fully corroborated and removed from the region of doubt by the body of evidence collected by the Commission.

Pillage had begun in Adrianople before the Bulgarian troops entered the town, and continued until the occupation and the installation of the army was an

114 ![]()

accomplished fact. Innumerable scenes have been described by eye witnesses. A considerable number,—which could be indefinitely increased,—will be found in the Appendix.

Even during the entry by the Bulgarian soldiers the streets were occupied by the indigenous mob, which pillaged all the Turkish public buildings, beginning with the military clubs, and attacked private houses, beginning with the vacant abodes of the Turkish officers. Patrols were hastily sent out, who lost themselves in the labyrinth of streets, and the people were instructed to whistle for their aid. However, the mass of the Turks feared reprisals on the part of the Greeks. The patrols wandered hither and thither punishing a few malefactors to the cries of "Aferim" (Bravo!) from the Turks. But the Turks themselves told Mr. Mitov, who described the scenes to us, "you can not be everywhere at once." And so the pillaging went on.

An official (whose name we are not permitted to disclose) went through the streets on the second day of the occupation. Djouma-bey, the Secretary of the Vali, pointed out crowds of men and women on every side, carrying off the goods they had stolen. Going into the Hotel de Ville, he asked for a patrol and went out with Major Mitov. Everywhere the same sight met their eyes. A perpetual stream of women, making off with their plunder. He threatened them with his stick. Mr. Mitov pointed his revolver. The women made off, dropping their bundles; then, as the authorities passed on they saw the same women coming back and picking up their booty. They arrived at the mosque, where the populace had stored its household goods. Standing at the door the Bulgarian officer ordered the pillage to stop and the pillagers to go out one by one. As they passed out they were hit with the stick and the butt end of the revolver. The women, however, would not let go; in spite of the bastinado to which they were treated they stuck to their thefts. There were too many of them, both men and women, to be taken up and punished, and they took advantage of this accident of superior strength.

By the third day the patrols were regularly established; order began to be restored. Nevertheless pillage and robbery went on, though under new forms suited to the new conditions. Sometimes the thieves dressed themselves up as soldiers and having obtained entrance to a house in the guise of a patrol, plundered at their ease. It was at this point that the Bulgarian soldiers in their turn began to follow suit, or rather to cooperate with the rest in a new kind of division of labor. There is evidence to show that the patrols worked to protect— the thieves, on condition that they might share in their booty. Major Mitov himself admitted that the soldiers had, to his knowledge, often been induced by their Greek hosts to take part in pillage, every possible means of persuasion being tried as inducement.

Here again the authorities have simply had to admit their powerlessness. The member of the Commission responsible for the inquiry was told that a

115 ![]()

captive soldier "pomak" (i. e., a Bulgarian Mussulman), well known in one of the consulates, was given a written permit to go about as a "free prisoner"; but on attempting to make use of his permit, he was robbed in the streets by the regulars, who stripped him of everything down to his boots. He returned to the consulate barefoot and a complaint was sent in to Commander Grantcharov. All he could do however was to renew the poor devil's permit and give him a medjide (4 1/2 francs) out of his own pocket, to buy shoes.

Pillage even went on at the Bulgarian consulate in Adrianople. The consul, Mr. Kojoukharov, on returning thither from Kirk Kilisse, whence he had been transferred, found his trunks had been emptied. Mr. Chopov, chief of police in Adrianople, told us that he was unwilling to make inquiry into Mr. Kojoukharov’s case, because he was a Bulgarian. On the other hand, Mr. Vasov told us that he refused to make domiciliary investigations, "to avoid disturbing the people," and perhaps also to avoid creating new opportunities for pillage. Such investigations were made, however,—and Mr. Vasov mentioned them himself,—in search of soldiers in hiding and disguise.

Moreover, complaints and requests for inquiries poured in from the pillaged people, especially from the Turks, to the number of two or three hundred a day, according to Mr. Mitov. Thereupon domiciliary investigations were instituted, with excellent results in many cases. A quantity of goods stolen from the Turks were discovered in the houses of the Greeks and handed back to their owners. The chief of police opened a depot in the Hotel de Ville for goods of doubtful origin and unknown ownership; and Mr. Chopov told the Commission that the stolen goods were brought in by the cart load. Certificates were then issued bythe municipality stating that ownership of the goods had been acquired not by theft but by purchase. Mr. Mitov explained to the Commission that this became an ingenious and novel method of claiming ownership of certain goods which had in fact been bought, but at a very low price, by Jews and Greeks.

Domiciliary investigations of course furnished their own crop of abuses. Here again, however, Greek complaints can not always be taken as expressing the truth, and nothing but the truth, as is suggested by one case cited by Mr. Machkov. In his report he says: "Soldiers, armed with muskets, carried off a quantity of jewelry and precious antiques from two Greeks, the brothers Alexandre and Jean Thalassinos; they wrenched rings and bracelets from the hands of their sister."

A great deal has been said about the pillage of the carpets and library of the celebrated mosque of Sultan Selim. The evidence collected by the Commission enables us to settle this point. That the Bulgarian authorities, as soon as circumstances permitted, took every reasonable precaution for safeguarding the mosque is clear. It is however not true, nor did the interested parties ever try to spread the belief, that the mosque was not pillaged at all. In the first confusion the fine building served as a place of refuge and was filled by the

116 ![]()

wretched furniture of the poor Mussulman families who sought an asylum there. Mr. Mitov told us how these Mussulmen took their domestic utensils and their rags with them when they left. Mr. Chopov added that the carpets of the mosque were not injured and the representative of the military governor of Adrianople who was attached to the member of the Commission responsible for the inquiry certainly made no complaints on the score of this alleged vandalism.

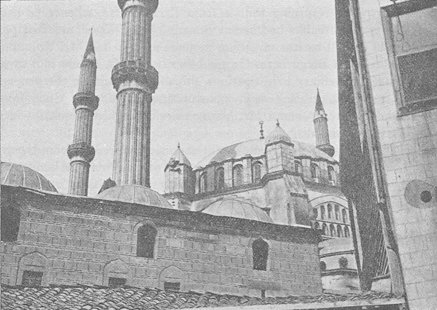

Fig. 15.—Mosque of

sultan Selim

A cupola of the dome

rent by an explosive shell

The case of the library

is different. During an entire day it was at the mercy of the populace,

thanks to the existence of a private entry overlooked by Mr. Mitov at his

first visit. On returning to the mosque in the course of the next day he

perceived clear traces of pillage. Books were lying on the floor; some

had been torn from their bindings; everything believed to have been of

value had evidently been removed. In Adrianople and in Sofia it is said

that foreign orientalists, enlightened connoisseurs, were happily inspired

to save precious manuscripts and rare volumes by buying them at their own

expense. If the happy possessors, now that all danger of destruction is

over, restore its property to the mosque, this action will have been admirable.

The evidence of Baroness Yxcoull shows that order was restored in the mosque,

as in the town of Adrianople, from the third day of the occupation.

117 ![]()

THE BULGARIAN ADMINISTRATION

Let us now, leaving on one side other characteristic incidents, which could be multiplied ad infinitum, consider the general criticism passed on the Bulgarian administration, during the four months of the occupation,—March 13/26 to July 9/22. That the general impression on the part of the inhabitants of Adrianople today is decidedly unfavorable to the subjects of King Ferdinand is undeniable. Those representing Bulgarian authority have thus ample opportunity of estimating at their true value the official expressions of gratitude which were extended to them on behalf of the heterogeneous population of the town. The Turks are only too glad to pass once more under the sway of their national government. Both interest and patriotism have always made the Greeks hostile to the Bulgarians.

The testimony of foreigners is mixed. Mr. Klimenko, head of the Russian consulate during the siege, authorizes us to state in his name that up to his departure from Adrianople on April 7, he had no complaint to make of the Bulgarian regime. The judgment of the brothers of the Assumption, and to some extent of the Armenians, is equally favorable. The documents annexed to this volume contain a list, supplied by the authorities themselves, of the measures taken by the Bulgarian authorities to restore order and satisfy the various nationalities concerned. On the other hand, Mr. Gustave Cirilli, in his Diary of the Siege, speaks of the Bulgarian administration as creating "an irresistible tide of distrust or aversion"; due, according to him, "not so much to vexatious exactions which alienated the sympathies of the inhabitants," as to the extravagant nationalism of the Bulgarians, their efforts to impose their religious observances and language. At the same time Mr. Cirilli does justice to the administration of the last commander, Mr. Veltchev, of whom Mr. Machkov speaks so ill, describing his system as "the hand of iron in the velvet glove."

The Commission's competence was, of course, limited to a record of the externals of the regime. It is well known that the municipality retained its powers under the Bulgarian domination and that a majority on the council belonged to the nationalities (three Bulgarians, three Greeks, three Turks, two Jews, one Armenian). The Turks were better disposed than the other nationalities to a Bulgarian administration which saved them from pillage, and frequently passed official votes of approval upon it. The Greeks, on the other hand, did not conceal their hostility. Amusing stories are told of meetings between Mr. Polycarpe, the Greek Metropolitan, and representatives of the Bulgarian power, the former being visibly torn between deference due to constituted authority and inward revolt. The most exaggerated statements about the misconduct of the Bulgarians emanate from Greek sources. The measures taken by General Veltchev are the natural result of the temper of bold bravado which again took possession of the conquered or hostile peoples at the close of the occupation period. Mr. Bogoyev indeed told us (see Appendix G, 5)

118 ![]()

that Mr. Veltchev called the Turkish and Greek notables together and stated that he should hold the Greek Metropolitan specifically responsible in the event of any rebellion of the "Young" Greeks. The events described above on the Aegean coasts justified only too fully the Bulgarians' suspicions of the Bishop of Adrianople as the center of the patriotic Hellenic agitation directed to the recovery of Thracian autonomy.

In the irritation produced by national conflict, reinforced by the "vexatious exactions" to which the natives were subjected, lies the explanation of their verdict on the Bulgarian regime in Adrianople. Wholesale and retail merchants were thoroughly displeased with the new organization of the wagons employed for importing goods as well as with the maximum prices of commodities fixed by the Bulgarian authorities. The highly interesting explanations of Mr. Lambrev, apropos of Greek accusations on this head, will be found in the Appendix. They describe a most interesting social experiment whose aim was to harmonize middlemen's profits with the legitimate needs of the population.

Complaints also came from the owners of houses occupied by Bulgarian officers. Comparisons between Bulgarian and Servian officers are generally disadvantageous to the former. Even friends of the Bulgars admit that, as far as externals go, the Servians had "a more distinguished appearance" and that their bearing made a favorable impression, in contrast to Bulgarian "arrogance." Obviously, therefore, the Servian officer was, generally speaking, preferred as an inmate to his colleague. All the same it is also probable that, in the troublous days, many people were glad enough to have a Bulgarian officer in the house to keep off the blows of the mob and the dubious protection of the patrols. To this the Greek notables apparently afforded an exception, however; in certain cases they met the demands of the billeting committee with a blank refusal ; [The members of the Committee were Fouad-bey, the Mayor (a Greek doctor named Courtidis), an Armenian and a Jew.]and it was sometimes necessary to use compulsion against them. For example, no suitable lodging being forthcoming for General Kessaptchiev, he was obliged, on his return from Salonica, to put up at the Hotel du Commerce.

It can hardly be denied that there were cases when departing officers,—and not only Bulgarian officers,—did take with them certain "souvenirs" of the houses in which they had dwelt. It is, however, a gross exaggeration to speak of "train loads of pseudo war booty" being sent to Sofia. Mr. Chopov himself has explained the "Chopov case" (see Appendix G, 6) and his explanation could be confirmed, if needful, by the evidence from Turkish merchants. There has been a certain amount of talk about the story of Rodrigues, an Austrian subject, and it is said that the Bulgarian authorities have promised the Inquiry Commission to assign responsibility, and refund the loss. Laces, ribbons and even ladies' dancing slippers are said to have been carried off from a house in Adrianople, the residence of Nissim-Ben-Sousam.

119 ![]()

A Sofia paper, the Dnevnik, reported the naive admissions of Mr. Nikov, a Bulgarian officer and another devotee of oriental knick-knacks. In the early days of the occupation, he saw an old Greek woman carrying a seat of exquisite workmanship, adorned with carvings in oriental taste. All the trouble and privation he had had to undergo in the long months of the siege, in the muddy trenches, came to his mind and strengthened his conviction that he had a right to the precious piece of furniture. So, instead of conveying it to the depot opened by Mr. Chopov, he took it from the old woman, whose right to it was the same as his own. These officers came and gave evidence before the Commission or made public confession. There must, however, be others who refrained from appearing or saying anything. The carpets of the mosque of Sultan Selim were not touched and Mr. Chopov bought his fairly and squarely. But a member of the Commission was told that there was a time when the price of carpets fell markedly low, and admirable "windfalls" were secured in Sofia.

Again, sums of money are said to have been extorted for the liberation of captured individuals. Mr. Chopov, for instance, speaks of the case of the Vali Habil, whose freedom is said to have been obtained by these means. The Greeks in Adrianople say that he paid the huge ransom of ?T40,000. Such a scandalous transaction, had it really taken place, could not have passed unnoted; the story must be added to the legends circulated by the Greeks. At the same time the Commission would not venture to affirm that there were no abuses of this character, on a more modest scale. Tales are told in Adrianople of one Hadji-Selim, tobacco merchant and leader of a band, who was finally executed but whom, previous to his execution, they tried to compel to sign a cheque for ?T1,000 to his credit as a deposit in the National Bank of Bulgaria. Hadji-Selim is said to have signed but to have repudiated his signature in prison on the eve of execution, in the presence of the public prosecutor, the director of the Ottoman Bank who had had the cheque presented to him, his assistant and some officers.

These incidents, of interest to the moralist in the tangle they present of human weakness and honest effort, conscientious performance of duty and the crimes that follow in the conqueror's train, may be left to the judgment of the reader: a judgment that must allow for the exceptional circumstances of a great city in a state of siege. There could be no question, at this stage, of the normal administration established later on when the Turks returned as a "tertius gau-dens," when war broke out again after the disagreement between the allies and the violation of the first conventions. We have only now to report the events of the last period of Bulgarian occupation.

THE LAST DAYS OF THE OCCUPATION

On July 6/19, the administrative officials in Adrianople received orders to return to Bulgaria. The telegram arrived at 11.30 at night; the public knew

120 ![]()

nothing of it. At midnight the Rechadie Gardens were still full of people, the inevitable cinematograph films passing before the idlers' eyes. The departure of the Bulgarians was sudden. That is why they left their cannon, their store of ammunition and their supplies behind them; why also the accusations of pillage and outrage made against them fall away, since the very conditions of their departure made them impossible. In their haste they even forgot to remove the sentinels stationed at the doors of some protected houses. Bulgarian merchants complained bitterly of the secrecy with which the move was carried out by the authorities. It did indeed take everybody by surprise.

The authorities left Adrianople on the night of July 6-7 (19-20). The Turks however did not arrive. In the city itself Major Morfov, with his seventy gendarmes, and Commandant Manov, represented law and order, but there were no regular authorities at the station or in the Karagatch quarter, and here deplorable incidents took place. On July 7, some eight military trains left the Karagatch station; by the time the last train but one departed the marauders were already at work and had to be fired at from the carriage roofs. A fire broke out in the depots, started, say the Greek witnesses, by a detachment of Bulgarian infantry on its way from the south towards Mustapha Pasha. Some of these same soldiers told the brothers of the Assumption that the depots had been fired by peasants, the Bulgarian army being beyond the station and the depots at that time. According to their statement the soldiers only set fire to the barracks, which was also used as an arsenal. Anyhow, there is no doubt that pillaging began under the eyes of the Bulgarians as they got on board the trains ; that the pillagers were peasants from Karagatch and the adjoining districts, Tcheurek-Keui and Dolou-djaros; that the soldiers tried to fire on them but the departure of the trains left them free to continue their pillaging. The peasants then armed the Turkish prisoners working on the railway—the same, evidently, of whom Mr. Bogoyev speaks. During the evening of July 7/20, the inhabitants of Karagatch laid in stores of petrol, meal, etc., taken from the depots.

Time went on and the Turks did not appear. The Bulgarians accordingly returned on the morning of Monday, July 8/21. They began by disarming the Turkish prisoners. The scene described by Mr. Bogoyev, when the Bulgarians fired on the prisoners and slew at least ten of them, must have occurred at this stage. According to the explanation given at the time by the Bulgarian officer holding the station, the prisoners tried to take flight in the belief that the Turkish army was already in Adrianople. When the Bulgarians asked where the Turkish prisoners could have got arms, they were informed that these were supplied by the population. From that time on the Bulgarians watched the inhabitants of Karagatch vigilantly. Their houses were visited and they were ordered to hand over whatever had been taken by anybody from the depots within a certain time ("up to 3 o'clock in the afternoon), after which requisition •would be made by force and punishment made.

121 ![]()

Towards evening domiciliary visitations were in fact instituted. It is not quite clear how the forty-five persons arrested were selected. One of them, the sole survivor, Pandeli (Panteleimon), declared that it was his twelve-year-old son who had taken some meal from the depot; he, the father, had restored the booty, as was ordered, the original order having been that the goods restored should be deposited in the streets, but after that he and his comrades in misfortune had been detained to carry the sacks to the station. Pandeli described what followed in detail and his story, tested by the Commissioner making the report by comparison with two other witnesses, one grecophil, the other bulgarophil, is here reproduced. He said:

In the evening (July 8/21) the wretched creatures were bound together in fours by their belts and conducted along the Marache road by an escort of sixty soldiers. Their money and watches were taken from them before they were bound. They were told that they were being taken to Bulgaria, but when the soldiers got near the bridge across the Arda, someone shouted, "Run quickly, the train is coming!" They crossed the bridge and reached the opposite bank. There they were placed in line, their faces to the river, and pushed into the water. A horrible scene followed. While the poor devils floundered about the soldiers fired on any whose heads appeared above the water. Pandeli owed his life to a desperate movement. As he fell into the water he broke with an effort the belt fastening him to his companions. In the water, alone and free, he began to swim, raising his head from time to time. The shots directed at him luckily did not hit him. He then pretended to be dead, and lying on his back, allowed the current to carry him along. For some time he lost consciousness, then found himself stopped by a tree. He crawled up the wooded bank on all fours. A coachman seeing him fled, terrified by his looks. During the night he made his way back to the Hildyrym quarter and went to the house of his apprentice. (Pandeli is a carpenter in the Karagatch steam mills.)

The photograph (p. 122) shows the corpses of some of the forty-four victims who were fished out of the river some days later. The miserable episode did not come under the cognizance of the responsible Bulgarian authorities, but there can be no doubt of its truth. The panic and excitement of the final moments of departure can not be held to exonerate those guilty of it. The member of the Commission who made inquiry on the spot, learned from the brothers of the Assumption that other persons were arrested for acts of pillage, but they were left as they arrived at the station, people shouting to the escorting soldiers from the carriages of the last train: "Hurry up, the train is going." This happened at three o'clock in the morning on July 9.

The departure of the Bulgarians was then a hurried one. It follows that it is false to urge that "the Bulgarians, knowing that the Turks were going to return, had made every preparation for the final massacre"; that "they were going to massacre the Mussulmen, while the Armenians, whom they had carefully armed, were to be compelled to exterminate the Greeks." The Bulgarians

122 ![]()

Fig. 16.—Victims thrown into the Arda and drowned

123 ![]()

made no preparations for their own departure, and the "nightmares" spoken of in the quotation from Mr. Pierre Loti's article in L'Illustration, never had any existence save in the lively imagination of the Greek population which had been heated by agitators. The dramatic picture of the "last night," as described by the eminent French author, thus betrays but too distinctly the sources from which it was drawn. Take one more detail in the same article. Mr. Loti speaks of a young Turkish officer, Rechid-bey, son of Fouad, "captured" by the Bulgarians in a final skirmish on the retreat. "They (the Bulgarians) tore out his two eyeballs," says our author, "cut off his two arms and then disappeared. This was their last crime." Assuredly Rechid's death did produce a profound impression in the Turkish army, where he had many friends. The Commission's investigator was shown the monument set up to his memory and recently consecrated on the Mustapha Pasha road. But as a matter of fact the Turk showed more equity than their admirer. When the investigator went to the office of the Tanine at Constantinople to verify the facts, he was told by the paper's special correspondent in Adrianople that in the affray Rechid had received a mortal wound from which death followed instantaneously. The mutilation was but too real; the torture, however, an absolute invention. Even at Adrianople people talked of Rechid's dismembered ears and hands—his hands being beautiful—but no one ever spoke of his eyes being put out.

The account given above

of affairs in Adrianople is far from exhausting the evidence collected

by the Commission. The curious reader may find fuller particulars in the

Appendix, where he can read the documents in proof of what we say. Unfortunately

the major portion of the depositions taken at Adrianople itself can not

be published or reported in detail since they were given confidentially.

But the reader will readily understand that it is those very depositions,

collected on the spot, which corroborate and support those used by the

Commission in this report.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]