Carnegie Endowment for International peace

Report ... to inquire into the causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars

CHAPTER III

Bulgarians, Turks and Servians

2. Thrace

In order to gain a personal idea of events in Thrace in the course of the two wars, a member of the Commission went to see the villages situated to the east of Adrianople. He visited the villages of Havsa, Osmanly, Has-Keui, Souyoutli and Iskender-Keui. The first of these had been visited by Mr. Pierre Loti, who gave a description of it in L'Illustration. Unfortunately while describing the Bulgarian atrocities in this mixed village, Mr. Loti has not been informed that two steps off, at Osmanly, there was a Bulgarian village where the Turks had taken their revenge.

Havsa is composed of two quarters, the Mussulman and the Christian. The Christians here call themselves "Greeks" but they are Bulgarian patriarchists. Their quarter was not burned. The whole population remained there. The Turkish quarter, on the other hand, was almost entirely burned. The Turkish population fled the village on the Bulgarians’ approach, that is to say

124 ![]()

at the beginning of the first war. These Turks took refuge in Constantinople and in Asia Minor. They are now beginning to come back; fifty or sixty families have arrived from Brousse, the Dardanelles and Akcheir. One might have thought that everyone had gone; there could have been no one left to suffer atrocities. Unhappily there were some exceptions. Rachid, an aged inhabitant of the village, told what follows to a member of the Commission. Four Turkish families had been unwilling to take flight. They remained. The names of the heads of these families were Moustafa, Sadyk, Achmed Kodja, and a fourth whose name has escaped 'us. These families were slain by the Bulgarians, who also put to death Basile Papasoglou, Avdji, Christo, Lember-Oghlu and Anastasius. All the women were outraged, but it is not true, as Mr. Loti asserts, that they were killed. Only one woman, Aicha, was killed; and the wife of Sadyk, who was among the slain, went out of her mind.

In the village there were two mosques. One of the mosques was turned into an ammunition depot. Another, described by Mr. Loti, was really seriously damaged. The member of the Commission found traces of blood on the floor. The rubrics from the Koran in the interior were in part spoiled, the Moaphil place destroyed, the marble member half broken, the pillars smashed. The dung seen by Mr. Loti in the minaret had gone, but some traces of it remained. A hole made in the cupola enabled one to get above the higher portion of the ceiling; a hole had been made in the middle of the ceiling and Rachid stated to the member of the Commission that from here, too, dung was spread on the floor below. The sacrilegious intention was even more clearly visible in the way in which the cemetery was treated. "All" the headstones were not broken, as Mr. Loti states, but some of them were. It is likewise true that one of the graves is open. In the bottom of the trench the member of the Commission found the remains of a brandy bottle; relic of a joyous revel! Justice compels the further remark, that the authors of this infamous deed are unknown, and that there are grounds for attributing it to the people of the locality, rather than to the regulars. It was noted that the miscreants confined their attentions to recent headstones and graves, leaving the older ones.

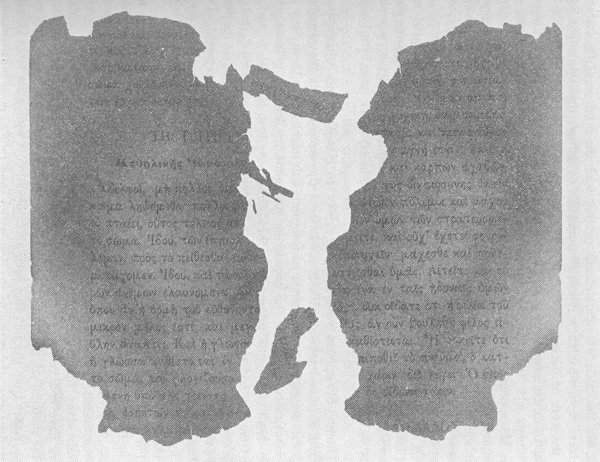

As has already been said, at a short distance from Havsa is Osmanly, a Bulgarian village, and there the Turks took their revenge, when they returned after the retreat of the Bulgarians. There were 114 Christian Bulgarian houses in the village. Not a single one was spared. The churches in the villages were burned and razed to the ground. The member of the Commission could see nothing but the outline of the precincts and the remains of the walls. Research in the interior recovered nothing but the debris of two chandeliers. The member of the Commission, investigating among the cinders, discovered some bits of half burned paper; they were fragments of the Gospel and the Sunday office, in Greek characters (see p. 125). The population had fled to Adrianople and from the Bulgarian frontier, i. e., towards Our Pasha. The whole of the cattle had been lost. Some dozen villagers were, however, working at the harvest in the village. They

125 ![]()

Fig. 17.—Fragments of the Gospel in Greek letters found in the ruins

of the Osmanli church

126 ![]()

explained to the member of the Commission that the oxen they were using belonged to Turks from other villages whose farmers they themselves were.

The next village is Has-Keui, a repetition of Havsa. The Bulgarian quarter (here they are called "Greeks," and they sing in Greek at church) remained intact, but the cattle were carried off together with the produce of the harvest. Our traveling companion, a Turk, ventured the hypothesis that this might have been the work of bashi-bazouks. But a peasant who was present and spoke in Bulgarian to the member of the Commission, said distinctly that it was "askers," the regulars who had pillaged and taken everything without payment. Going on to the Mussulman quarter, we found it still in a state of devastation. Of fifty-five houses only twenty-five remained. This portion of the village was empty, and it was explained to the Commission that the men of the village had gone to Adrianople in search of their families. The refugees who had returned (some twenty-five or thirty families) had gone to dwell in the Christian quarter.

Of the two mosques in the village, one had been entirely destroyed and razed level with the ground, and the school adjoining treated in the same way. The other mosque, which was converted into an ammunition depot, was also damaged, especially inside; several headstones in the cemetery have been broken down.

The two Mussulman villages situated between Has-Keui and Adrianople,— Souyoutli-dere and Iskender-Keui,—underwent the same fate as the preceding ones. Of the eighty-seven houses in Souyoutli only eight or ten, with forty or fifty inhabitants, remain. The population had gone to Anatolia. Those who return dwell among the ruins, which they arrange as best they can to shelter them from sun and rain. They call these wretched habitations "colibi" (huts).

Iskender-Keui suffered even more severely. Out of eighty houses but four or five remain. The population fled to Adrianople; all have now returned. The few houses still standing owe their preservation to the fact that they were occupied by Bulgarians. The mosque and school of the village were razed level with the ground.

The conclusion to be drawn from this description is, that as a matter of fact, at the outbreak of the first war the Bulgarians destroyed the Mussulman villages, that the population fled almost to a man, and that the national Mussulman institutions, mosques and schools, suffered specially. Evidently these are not isolated or fortuitous events. They represent national tactics. Bulgarian officers have endeavored to explain this conduct to the Commission, pleading that the material of the houses was used to make winter cantonments for the army. Apart from the fact that such an explanation is equivalent to an avowal, it is inadequate to the extent of the devastation, and fails to meet the destruction of places of worship and schools.

Coming now to July, the Bulgarians began to retreat while the Turks assumed the offensive. Thrace again became the theater of war. Enver-bey is

127 ![]()

accused with considerable unanimity of having sent Arabian and Kurdish cavalry ahead of his regular troops. These "Arabs" are often indicated, in the victim's stories, as being the authors of crimes. The Commission has collected a body of evidence to the effect that Turkish officers themselves sometimes warned those whom they were protecting of the approach of the "Arabs," and told them to be on their guard. An "Arab" soldier, a Catholic, actually admitted to one of his friends that the express orders of their captains were first to burn and ravage, then to kill all the males, next the women (here again all took flight) ; and that he had personally carried out the orders given him. We should not mention this story were it not that it comes from an excellent source, the name of the soldier being known to us, though we naturally refrain from giving it here.

These remarks made and conclusions established, we may pass to another part of Thrace, in order to follow the advance of the Turkish offensive, in relation to alleged excesses.

The member of the Commission had opportunity of free conversation with the Bulgarian refugees in Constantinople itself. They passed through Constantinople in groups. The Commission's member did not encounter the group of ninety persons from the villages of Tchanaktche, Tarf, Yeni-Tchiflik, Seimen and Sinekeli; nor the group of 190 from Baba-Eski and Lule-Bourgas. But the third group of sixty-two persons was still there. There were hardly any but old people, women and children. Most of them Were refugees from the villages of Karagatch (130 houses), Koum-seid (twenty-eight houses), and Meselim (ten houses), peopled by Bulgarians whom the Turks had brought from the village of Bourgas.

The following is the somewhat rambling story told to the Commission by an inhabitant of Koum-seid, who had reached Constantinople on the previous night, still haunted by recollected horrors:

It was Wednesday the 3d (16th). It was night and the village slept. All at once the Turks arrived. * * * The women and children were in a frenzy. * * * They asked for money. They killed many people. Nicolas the shopkeeper (bakal) was killed, Stoyan Kantchev was killed and also his son, fifteen years old. Next came the turn of Demetrius Stoyanov, Saranda Medeltchev, Demetrius Gheorgiev, Petro Stoyanov, Heli Athanasov and his brother. Cone Athanasov (these are his children); next Nicolas Gheorghiev, his wife and his twelve year old son; Demetrius Daoudjiski. Demetrius Christov, Christo Dimitrov—120 persons were gathered together in a single house; the Arabs arrived and asked them "Who are you ?" and they replied "We are Greeks." Thereupon they were asked for money. Everything was taken. Their pockets were searched. On the cries of the victims the cavalry came up. They did not touch the people; it was the "Arabs" who attacked them. The attack on the village did not last more than fifteen minutes. Then the Turks went away in the direction of Lule-Bourgas. * * * However, the next day more "Arabs" arrived. * * *

128 ![]()

As the Commission left Constantinople, they met everywhere in Thrace the traces of this Arab cavalry, following on local reprisals and hatreds, and the excesses of the bashi-bazouks who took advantage of the anarchy inevitable in transition from one regime to another.

Unhappily time did not allow the Commission to visit the places which bore the first brunt of the rage of the Turkish army when it resumed the offensive; but the evidence collected by them at Constantinople and in Bulgaria, when collated with the reports of special Armenian delegations and some well authenticated documents emanating from a fresh official source, may supply the defect of personal observation. It seems that at the moment of crossing the frontier, which had appeared for some months so definitively established by the Bulgarian conquest, two sentiments ruled in the Turkish army and population. There was vengeance on those of their Christian subjects who had joined friendship with the Bulgarian invaders in the first instance, and then with the Armenians. The Greeks, although they too had suffered at the hands of the Turks, were rather on their side. They too profited by Turkey's recovery to wipe out the traces of Bulgarian domination and reestablish their own national pretensions. They therefore hailed the Turks' return and often served them as guides and spies. The second feeling, natural enough in the Moslem population returning with the army to deserted villages, was to recover their goods and take them away from their new owners.

At Rodosto, retaken July 1/14, by 200 volunteers who arrived on board an Ottoman gunboat, the first act of the reestablished Ottoman power was the following proclamation to the Christian and Jewish population of the Sandjak:

Anyone in possession of goods or arms belonging to the government or cattle or goods belonging to emigres in the local population, which have been appropriated during the Bulgarian occupation, is invited to come and restore them to the Special Commission sitting at Rodosto. Two days' delay are allowed, starting from today (July 5/18) for those who are in Rodosto, three days for those dwelling in the villages. After the lapse of this delay any one found with appropriated goods in his possession will be treated with all the rigor of the laws.

But the volunteers and emigres returning home did not wait for the end of this nominal delay. The moment of their arrival they began pillaging and massacring the indigenous population. The volunteers had but just disembarked at Rodosto when they slew the Bulgarian commissary who handed the town over to them; they divided themselves into groups, with four or five bashi-bazouks at the head of each, and hastily organized pillage and massacre. They slew the Armenians whom they met in the market place, then the people being once shut up in their houses, ransacked the houses under pretext of searching for Bulgarian soldiers and officers there. The foreign consuls intervened; then the assailants turned their activities to the country outside the town, where no

129 ![]()

control could be exercised. The results were nineteen corpses buried in Rodosto and eighty-one victims disappeared and evidently slain in the fields. This last figure should be higher,—some put it at 300. The more well-to-do had to pay for their safety between twenty and sixty Turkish pounds a head. Money, jewels and watches disappeared. Even so they were well off, for at eight hours’ distance from Rodosto, in Malgara, the catastrophe assumed much larger proportions. There the population was taken by surprise; there were no consuls. The heads of the Armenian community were arrested by the Governor at Rodosto, The Bulgarian police had just quitted the town, which for a day remained without any authorities or public force (July 1 and 2, old style). We can not here transcribe the eloquent story told by the Armenian delegation of what happened at Malgara in this state of anarchy.The reader will find it in the Appendix. But some points, common to the whole of this work of destruction, may be mentioned. Here again the motive is the same as at Rodosto and everywhere else; the military commander of the place addresses the Armenian notables summoned before him, in these terms:—-"Armenian traitors, you have in your possession arms and other objects stolen from the Moslems." A sub-lieutenant uses the other argument referred to:—"You other Armenians, you have largely assisted the Bulgarians, but today you shall have your reward.” Such terms encouraged the population not to wait until legal measures were taken. On the second and third days of the occupation public criers in the Armenian quarters order "those who have stolen goods belonging to Moslems or who are in possession of arms, to give them up." On the fourth day an opportunity for beginning the attack presents itself. Two terrified Armenians, on being called on by the soldiers to show them the Ouzoun-Keupru road, run away instead of answering. The signal is given; the soldiers, the crowd, put lighted torches soaked in petrol to the houses of the culprits; and the burning of the Armenian quarter begins. At the same time pillage and massacre are going on in the market. Some Armenian soldiers stop the fire, but it breaks out again in the market and thanks to the strong wind assumes terrifying proportions. Explosions of barrels of benzine, alcohol, etc., are heard; the crowd takes them for hidden bombs. Finally the Kaimakam, the representative of civil authority, arrives at Malgara, accompanied by the captain of police and a policeman. Even by standing surety for their lives, he hardly succeeds in persuading-the frantic Armenians to come out of their hiding places and organize a little band of some fifty to sixty young people who get the fire under. Results, in the town itself, to say nothing of the environs: twelve Armenians killed, ten wounded, eight disappeared, seven imprisoned, eighty-seven houses and 218 shops burned; a material loss amounting to ?T80,000. [Le Jeune Turc of August 12 actually admits that 139 houses and 300 shops were burned at Malgara. It adds: "with the exception of two houses the entire village of Galliopa, consisting of 280 houses, was destroyed by fire; 299 houses were the prey of flames in eleven Christian villages, thirty-five persons were killed and nine wounded.] This time there was also an epilogue.

130 ![]()

An Ottoman commission of inquiry tries to cast the responsibility of the pillage and assassinations * * * on the Armenians themselves.

The real massacre begins however when the Turkish army meets Bulgarians on its route, and the events described at Rodosto and Malgara fade before those which took place at Boulgar-Keui, "a Bulgarian village," as its name shows. Boulgar-Keui is, or rather was, a village of 420 houses some miles from the town of Kechane and not far from another village of 400 houses, Pichman-Keui, whose fate was similar. The information collected by the Commission as to these atrocious events comes from different sources and the evidence agrees in the smallest details. The refugees, women for the most part, scattered in all directions. They were found at Haskovo and Varna in Bulgaria, where two agents of the Balkan Relief Society questioned them and transmitted their depositions to a member of the Commission,—depositions that though coming from places very far distant from each other are identical in terms. Another member of the Commission was able to meet in Constantinople a male survivor of the horrors of Boulgar-Keui and thus obtained possession of some unpublished Greek official documents which confirm and complete the oral depositions. From all these sources an absolute certainty emerges that the purpose was the complete extermination of the Bulgarian population by the military authorities in execution of a systematic plan.

These events recall those at Rodosto and Malgara, but the end is different. The Bulgarian peasants, like the populations of the towns referred to, had as a matter of fact appropriated the goods of the Turkish emigres, their coats, domestic utensils, cash, etc. The Turkish soldiers in their turn lay hands on what they can find; they demand money, they carry off clothes, they lead off the big cattle over the frontier to the village of Mavro. Thus a whole week passes, July 2-7. Soon, however, everything changes. The order is given to collect the whole male population at the bottom of the village to receive instructions. The witness spoken of above believed the order to be a lie and preferred remaining at home, thereby saving his life. Nearly 300 men appeared. They were all killed on the spot by a fusillade. Only three men escaped, one of them being wounded (John K. Kazakov). The depositions of the women complete the picture. At Haskovo they told the agents of the English Relief Committee that the Turks went from house to house seeking for male inhabitants over sixteen years of age. Two shepherds, Dimtre Todorov and George Matov, added that the Greeks helped the Turks to tie the Bulgarians' hands with cords. A young woman refugee at Varna described how her husband, father and two of her brothers were shot in front of their house. Another stated that at Haskovo she had seen the Greeks sprinkle her husband and some other men with petrol and then burn them. Other women at Varna confirmed this horrible story and added that the number of victims who perished in this way was twenty-three. A shepherd saw the same scene, hidden in a neighboring place of refuge. The

131 ![]()

women put the total number of men killed at Boulgar-Keui at 450 (out of 700). The Constantinople witness adds that all this was going on up to July 29 (old style) when he left the village. At the end of this period the Turks began sticking notices on the walls that there was to be no more killing. A portion of the population believed it and returned. But as the male population returned killing began again by twos, threes and fives. The people were led into a gorge and there shot down. The witness saw that at Pitch-Bonnar and at Sivri-Tepe: in the first place he saw as many as six corpses and recognized one of the six as the "deaf" Ghirdjik-Tliya.

The methods employed with the women were different. They were outraged, and Greeks, clad, according to the witnesses, in a sort of uniform, did the same as the Turks. In the villages of Pichman, Ouroun-Begle and Mavro, the Greeks were indeed the sole culprits, and they outraged more than 400 women, going from one to another. Young men who tried to defend their betrothed were taken and shot. A woman of Haskovo described how her little child was thrown up into the air by a Turkish soldier who caught it on the point of his bayonet. Other women told how three young girls threw themselves into a well after their fiances were shot. At Varna about twenty women living together confirmed this story, and added that the Turkish soldiers went down into the well and dragged the girls out. Two of them were dead; the third had a broken leg; despite her agony she was outraged by two Turks. Other women of Varna saw the soldier who had transfixed the baby on his bayonet carrying it in triumph across the village.

The outraged women felt shame at telling their misfortunes. But finally some of them gave evidence before the English agents. They said that the Greeks and Turks spared none from little girls of twelve up to an old woman of ninety. The young woman who saw her father, husband and brothers perish before their house was afterwards separated from her three children and outraged by three Greeks. She never saw her children again. Another, Marie Teodorova, also saw her husband killed before her eyes, and then, dragged by the hair to another house, she was outraged by thirty Turks. Two of her three children were seriously wounded and one of them died at Varna. Sultana Balacheva is the old woman of ninety with wrinkled face, from the village of Pichman, who was outraged by five Turks.

Here are some extracts from secret Greek reports not intended for publication which will serve to show that the same outrages repeated themselves in all the countries in which the Turks took the offensive: "Yesterday evening (July 4/17) from the first hour of the night (t. e., sunset, alia Turca) to six o'clock, the Turkish population has invested the Greek village of Sildsi-Keui (Souldja-Keui to the northeast of Rodosto), set fire to it and massacred the whole village, women and children included, 200 families in all. The catastrophe was wit-

132 ![]()

nessed by so and so [Since all these places have remained in possession of the Turks the necessity of concealing the names of the authors of the documents will be understood.] * * * No one escaped." Isolated massacres of shepherds and workers in the fields, during the same day, by Turkish soldiers and inhabitants, are also mentioned in the villages of Simetli, Karasli (both southeast of Rodosto), Titidjik, Karadje-Mourate, Kayadjik, Akhmetikli, Omourdje and Mouratli. On the same day (July 4/17) Turkish soldiers killed at Kolibia near Malgara the hegoumenos (abbot) of the Monastery of Iveria, Eudocimus, the priest Panayote and some other persons.

This was but the beginning. Since the population of the neighboring villages fled to Kolibia the Turks "after killing in the interior of the church, burned all the families of the neighboring villages that had found refuge there" (report on July 9). In Has-Keui, another village near Malgara, the Turks burned "a considerable number of families." In the same village (report of July 12) the officer ordered the mouktar (head man of the village) to procure him three girls for the night, "otherwise you know what will happen to you," the officer added, showing his revolver. The mouktar refused and bade the officer kill him rather * * * Then "the men were shut up in the church * * * all the women were collected in a spacious barn and the soldiers banqueted for twenty-four hours, outraging all the women from eight to seventy-five years of age." The army took with it quantities of young girls from each village. At Kolibia a young girl, pursued by a soldier, fell from a window. While her body was still breathing the soldier assaulted her.

The Greek report is at pains to add: "The caimacams demand that a declaration be signed to the effect that all these infamies * * * were committed by the Bulgarian army." The words explain why in the declarations published in August, 1913, in Le Jeune. Turc, signed by Greeks and written in the name of the population, the accusations against the Bulgarians are so numerous. The object was in fact to clear the Ottoman troops of all the crimes committed. [For example, at Has-Keui where according to the authority cited there were "a considerable number of families" killed or burned by the Turks. The following is the declaration of the village notables presented to the caimacam of the Haivebolou casa: "We deny categorically the malicious insinuations made against the Ottoman army and in rebutting them protest against crimes such as incendiarism and assassination perpetrated by the Bulgarian army in our town at Has-Keui and at Aktchilar-Zatar at the time of the Bulgarian retreat from these places." Signed Triandaphilou and Yovanaki, members of the administrative council of the casa, Greek notables: Father Kiriaco, representing the metropolitan, Dimitri, vicar of Has-Keui: Father Kiriaki, priest of Has-Keui: Polioyos, Greek commercial notability." See the Union July 24 which published in the same number a supplement entitled "Acts of Bulgarian Savagery in Thrace." The member of the Commission who visited another village of the same name, Has-Keui, near Adrianople, asked to see Constantinos, the priest of the village, who also signed a list equally long, of Bulgarian misdeeds there. (See Le Jeune Turc, Sept. 2.) The priest did not appear.]

Let us add one more report of July 9 on the events at Ahir-Keui (Aior-Keui to the east of Visa) which proves that the same system was applied over the whole area of the territories again occupied by the Turkish army: "Yesterday evening, July 7, the police selected to guard the inhabitants of Ahir-Keui sepa

133 ![]()

rated men, women and children. All the men they beat pitilessly and wounded many with oxgoads; outraged the young girls and women, giving themselves up to libertinism throughout the night."

In this way this portion of Thrace was absolutely devastated. The Greek report of July 9 states that the Ottoman army "massacred, outraged and burned all the villages of the casas of Malgara and Airobol. Nine hundred and seventy families from the casa Malgara and 690 from the casa Airobol, i. e., a population of 15,960 persons, have been either killed or burned in the houses or scattered among the mountains." If this be regarded as an example of the exaggeration not uncommon in Greek sources, confirmation may be adduced from a Catholic paper. [La Croix, August 24-25, 1913.] "A commissionaire who came from Malgara and arrived yesterday August 23, at Adrianople, assures us that the whole number of villages burned or wholly destroyed round Malgara is not less than forty-five. He stated that he smelt the intolerable stench of many corpses as he crossed the fields in the neighborhood of Kechane." A month after this deposition the member of the Commission who went to Constantinople heard there the story of a Greek, an English subject. About a thousand Bulgarians, men, women and children, were still wandering in the mountains, whither they had fled before the horrors described. But they were surrounded by Ottoman troops between Gallipoli and Kechane and exposed to every imaginable kind of suffering. The witness saw numbers of terrible scenes and took some photographs. Under his very eyes a Turk opened the stomach of a child of seven years and cut it to pieces. The witness is known in Constantinople, and it is extremely important that his photographs should not be mislaid. We might still be ignorant of facts that have come to our knowledge; the whole of this persecuted population might have remained there, wandering among the mountains, awaiting the last stroke from the soldiers who surrounded them. Very luckily the Greeks made the mistake of taking these peasants for compatriots; they received permission from the authorities (who shared the error), to lead them to Lampsacus, at the other side of Gallipoli. Here the missions concerned themselves with their lot, and the Greeks sent a special steamer to bring them to Prinkipo. Only then did they discover that they were not Greeks but Bulgarians. They were thereupon driven out into the streets. Thanks to the intervention of the Russian Embassy and the aid of the Bulgarian exarchate they were reembarked and sent back to Bulgaria. Chief among them were women from Boulgar-Keui, 412 of whom were seen by the English at Varna, as their fellow villager reported when questioned at Constantinople by a member of the Commission.

The space between the frontier ceded at London (Enos Midia), and the old Bulgarian frontier was traversed by the Turkish army in three weeks. The soldiers arrived with views deducible from the facts. An Arab Christian soldier of the Gallipoli army, of which we have spoken above, when asked why he had

134 ![]()

taken part in these atrocities, forbidden by his religion, replied confidentially in Adrianople, "I did as the others did. It was dangerous to do otherwise. We had the order first to pillage and burn, then kill all the men." * * *

Exceptions and distinctions were made however. There was a Bulgarian village, Derviche-Tepe, situated near two Turkish villages, one of which is called Khodjatli. When the Bulgarian army approached, during the first war, sixty Turks sought refuge with their Christian neighbors. They were given protection and did not suffer from the passage of the Bulgarian soldiers. Among others there was a rich cattle merchant who related the following story at Constantinople: "When the Turks returned they had the order not to touch the village. They said to the peasants: Be not afraid of us, since you saved our people; we have a letter from Constantinople to leave you in peace." But the exception confirms the rule. There were also exceptions in the contrary sense, as the history of the village of Zaiouf proves. Zaiouf was peopled by Albanians, Greek in religion. The next village, Pavlo-Keui, was Bulgaro-Moslem (pomak). During the first war the Zaioufians pillaged Pavlo-Keui, and then thought of baptizing the Pavlo-Keuians. They called a Greek priest, Demetrius, and he converted the village. The Turks, on their return, not only killed Demetrius; they razed the village to the ground. At the same time Aslane, the neighboring Christian village, suffered comparatively little. At Zaiouf, 560 persons were killed. On taking the offensive, the Turks transported their habits of pillage across the frontier. Among the villages destroyed in Bulgarian territory the Commission heard of Soudjak, Kroumovo, Vakouj, Lioubimits, etc. When according to the conditions of the treaty of peace, Mustapha Pasha had to be handed back to the Bulgarians, the Turks destroyed it completely, as is shown by the report of Mr. Alexander Kirov of October 19 (November 1), which is in the hands of the Commission. Mr. Kirov recounts that here too the return of the Turks during the second war was signalized by the massacre of the whole male population (eighteen persons). The old woman, who survived this appalling day, described how they killed them one by one amid the laughter and approving cries of the Moslem crowd. The headsman, a certain Karaghioze Ali, varied the mode of execution to amuse the mob. When a young man named Chopov asked to be killed more quickly, that he might not see such appalling scenes, Karaghioze Ali, smoking his cigarette, replied: "Be patient, my child; your turn is coming," and he killed him last. The old schoolmaster, Vaglarov, seventy years of age, was killed in the street, and throughout the day his head was carried by the beard from quarter to quarter. The mother of the writer of the report was killed on July 13/26, and thrown down a well. In the courtyard a portion of her hair, torn off with the skin, and her bloodstained garments, were found.

In Western Thrace traveling was impossible during the Commission's stay. Those places assigned to Bulgaria by the treaty of Bucharest, were inhabited equally by Greeks and Turks. After the departure of the Bulgarian army on

135 ![]()

July 9 and 10 (July 22 and 23), the country was occupied by the Greek army and the population little disturbed, "probably thanks to the nomination of a European Commission of Inquiry" (i. e., the Carnegie Commission), in the view of a Bulgarian journal, Izgreve. After its departure, however, September 6/19 up to the time of the definitive arrival of the Bulgarian army, the population was entirely in the power of the republican militia, i. e., of the Greek andartes am Moslem bashi-basouks, grouped by the priests, schoolmasters and secretaries of the Greek metropolitans (bishops). The Bulgarian population, expecting no good at the hands of this militia, was panic struck and threw themselves on all sides into Dede-Agatch, where there were still some Greek regulars. But the military authorities did not permit them to enter the town, and the crowd of 15,000 refugees were stationed a quarter of an hour's distance off, in the Bulgarian quarter and barracks. On September 19, the last Greek troops left Dede-Agatch with the steamer, and the Greek Metropolitan advised the Moslem volunteers of their departure. This is why the refugees, with the exception of about a hundred, had no time to seek shelter in the town. They were discovered by the bashi-basouks "of the militia, and led to Tere and Ipsala like flocks of sheep." They passed the night at Ouroumdjik, where their money was taken from them and the schoolmaster from Kaiviakov, with his wife from Baly-Keui, were massacred. On the morning of September 23, they met upon their way a company of Bulgarian volunteers, who delivered the larger part of the refugees from the bashi-basouks. But during the retreat, the bashi-bazouks succeeded in massacring about one hundred women and children who had remained behind with the baggage, and they took away 100-150 women and children. The rest took the road for Bulgaria with their liberators. But on the morrow, September 24, there was another encounter with the bashi-basouks, near the village of Pickman-Keui. In this encounter 500 were slain and 200 women and children made prisoners. Newcomers had raised the total to 8,000. At the river Arda new slaughter awaited them. After the crossing they counted again and were but 7,200.

The lot of those who

remained at Dede-Agatch was no better. A public crier shouted on several

successive days the orders for the Bulgarians to quit the town; recalcitrants

and those harboring them, to be punished like dogs. The frightened Greeks

filled several wagons with Bulgarians and sent them to Bulgaria. On their

way they saw two wagons full of Bulgarian women and children at the station

at Bitikili, and two other wagons at the station at Soffli. The number

of Bulgarian villages burned in Western Thrace amounts to twenty-two and

the massacred population to many thousands.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]