4. The Moravian Empire and Its Greek Apostles SS. Constantine-Cyril and Methodius

1. Franco-Bulgarian and Moravo-Byzantine alliances

2. Careers of Constantine-Cyril and Methodius

4. East Frankish Church and papal policy

5. Confirmation of Slavic liturgy, metropolis of Sirmium and East Frankish opposition

6. Pope John VIII, Methodius and Svatopluk of Moravia

7. Methodius’s visit to Constantinople; ruin of his work in Moravia

At the beginning of the second half of the ninth century a very energetic reaction arose in Moravia against the Frankish brand of Christianity and Frankish political influence, and this reaction was so sudden, so violent and so well organized that it upset all the Frankish plans of penetration and conquest in those regions. The consequences of this reaction were not confined to the political side; they were even more revolutionary in the ecclesiastical and cultural fields and here two new factors came into play: Byzantium and the Papacy, both of which had scarcely been heard of before in those lands.

Mojmir, the founder of the Moravian State, although he did not oppose directly the Frankish penetration among his subjects, was yet well aware of the danger which it represented for the independence of his realm. He particularly disliked the Frankish push into the territory of Pribina, since it was part of an encircling movement. Acting very swiftly, he attacked the pro-Frankish Pribina, drove him out of Nitra and annexed his territory to his own Moravian realm (between 833 and 836). Pribina took refuge with the Frankish Margrave Radbod, his neighbor, and

![]()

81

after accepting baptism and being later rewarded with the gift of a holding in lower Pannonia, became a zealous supporter of the Frankish missionaries. Frankish colonists were encouraged and made especially welcome in the region around Lake Balaton (Plattensee, Blatno), and here Pribina built himself a stronghold called Mosaburg. In order further to reward his zeal and the services which he had rendered to the Franks, Louis the German, King of the East Franks (843-876), gave him this territory in 847 as his hereditary property.

In chasing Pribina from Nitra, Mojmir arrested for centuries the Frankish push on the left bank of the Danube towards the Carpathian Mountains. His successor Rastislav (846-869) was able to extend his power as far as the Tisza, where his realm became contiguous to the Bulgarian Empire. His growing power aroused the jealousy of both the Franks and the Bulgars, and in order to crush him forever, Louis the German offered a pact to the Bulgarian prince Boris. The latter, afraid both of Rastislav and of Byzantium, gladly accepted the offer and even promised to receive Christianity from the hands of the Frankish missionaries, who seemed to him less dangerous than their Byzantine confrères.

But Rastislav was not unaware of this new development. He seems to have enjoyed very good relations with the Bulgarians at the beginning of his reign when the khagans were in conflict with the Franks; but he rapidly changed his policy and reacted to the move of Louis the German with a surprising counterattack. He was himself looking for an ally; and now he offered an alliance to the Byzantine Emperor Michael III. Consequently, [ sometime in 862, the population of Constantinople had the pleasure of greeting within the walls of the city "guarded by God” a strange embassy coming from the far Northwest where none but a few Byzantine traders and missionaries had ever penetrated.

Rastislav’s counter-move has seemed so surprising and improbable to many historians that until very recently some of them have strongly doubted whether a semi-barbarian prince was

![]()

82

capable of so brilliant a stroke of diplomacy. I have been able to establish, however, in a special study, [1] that the Moravian ruler did actually make such a move. Knowledge of Byzantium and of its glories was being spread even in such distant regions by traders who never ceased to maintain contact with the countries on the Danube and its tributaries. The Avars, especially in the last period of their existence, seem particularly to have encountered the influence of Byzantine civilization.

The Emperor Michael III would have preferred to receive an embassy from the Bulgarians, who were then in the center of the interest of Byzantine policy; but he and his counsellors were able immediately to grasp the importance of a Moravo-Byzantine alliance possibly developing into an encircling movement directed against the Bulgarian Khagan Boris, who, though still a pagan, appeared to prefer to accept his impending conversion from the Franks rather than from the Byzantines. Thus a Moravo-Byzantine alliance was concluded, the aim of which was to facilitate the cultural expansion of Byzantium. Rastislav, who dreaded the influence of the Frankish missionaries, besought the Emperor to send him Greek missionaries who could speak the Slavic language.

In the year 863, Rastislav in his “formidable fortress,” as the Frankish annalists called his residence, probably situated somewhere on the lower course of the river Morava, received a diplomatic and “cultural” mission sent to him by Byzantium. At the head of the mission were two brothers from Thessalonica (Slavic Solun’), Constantine-Cyril and Methodius, worthy representatives of the cultural revival which was taking place in the Byzantine Empire in the ninth century.

The two brothers were sons of a high-ranking officer (drungarios, a rank corresponding to that of colonel) attached to the command of the governor (strategos) of the province

1. See especially F. Dvornik, Les légendes de Constantin et de Méthode vues de Byzance (Prague, 1933), pp. 212 ff.

![]()

83

(thema) of Thessalonica. Methodius was born about the year 815 and Constantine in 826 or 827. Methodius chose an administrative career and — according to his biographer — was appointed by the Emperor to “the government of a Slavic principality.” Constantine was interested in scholarship and his biographer relates that, invited in a dream to select the most beautiful girl in a contest, he chose Sophia — Wisdom. After his fathers death, the Prime Minister Theoctistos himself took charge of Constantine’s education at the University of Constantinople, which had trained thousands of officials for the imperial service. At that time also he became the favorite disciple of Photius, the greatest humanist of the age, and eventually succeeded him at the university, when Photius took over the direction of the imperial chancery, and he also seems to have accompanied Photius when the latter was sent as ambassador to the Arab Khalif Mutawakkil. It was Photius who seems to have reconciled the brothers with the new regime after Theoctistos had been murdered by Bardas, uncle of the Emperor Michael III. Fearing that this upheaval and the changes which followed might have unfortunate consequences for him as a favorite of the murdered Prime Minister, Constantine left the capital and joined his brother in his monastery at Mount Olympus in Asia Minor.

Methodius seems to have chosen the monastic life on his own initiative. In the “canon” or liturgical panegyric in honor of St. Methodius, [1] there is an interesting passage which gives us some new and surprising details concerning him. The Saint is apostrophized:

“Holy and most glorious teacher, when you had decided to leave your family and your native country, your spouse and your children, you chose to go away into the wilderness in order to live there with the Holy Fathers.”

If this information is reliable, then it must be concluded that Methodius was married and had decided to become a monk, probably by mutual agreement with his wife — an arrangement which was not uncommon in Byzantium. The “canon” insists upon the free decision of the

1. Published by P. O. Lavrov, Materialy po istońi voznikovenija drevn. slav. pismennosti (Leningrad, 1930), pp. 122 ff.

![]()

84

Saint, a circumstance which excludes any kind of political pressure.

It was in this monastery that the new Emperor Michael and the new Patriarch Photius found the two brothers and persuaded them to accept an important religious and diplomatic mission to the Khazars in 860. A long report on this mission is to be found in Constantine’s biography. After their return from the Crimea, Methodius became abbot of the monastery of Polychron, while Constantine accepted the post of professor of philosophy at the patriarchal school which was being reorganized by Photius in the church of the Holy Apostles. [1]

Such were the men whom the Byzantine government was preparing to send as ambassadors to Moravia. Both accepted the new mission.

Constantine-Cyril was one of the finest polyglots and grammarians of the Middle Ages. Possessing a perfect knowledge of the Slav dialect of Macedonia — a fact which in no way reflects upon his Greek origin — he set to work to invent a special alphabet to express all the significant features of the Slavic language, and he brought this alphabet — known as glagolitic — to the Moravians as a special gift from the Emperor. Then, with his brother Methodius and his disciples, he started to translate the Holy Scriptures and the liturgical books into Slavonic. [2]

The Byzantine missionaries were warmly welcomed in Moravia and were easily able to out-manoeuvre the Franks, whose missionary

1. For details see F. Dvornik, “Photius et la reorganisation de l’Académie patriarcale." Analecta Bollandiana LXVIII (1950), pp. 106-125.

2. The dialect of the Macedonian Slavs was thus promoted to be a literary language and was adapted to the needs of the Slavs first in Great Moravia and later in other regions. It is customary to call the common literary language “Slavonic” or “Church Slavonic” and in its oldest version — from the ninth to the eleventh centuries — “Old Church Slavonic." Henceforward in this book the word “Slavonic” will be employed for all works written in the Macedonian dialect, the literary language of all Slavs in the oldest period of their cultural evolution.

![]()

85

methods the Slavs had grown to fear and hate. Thus the foundations of a new Slavonic Church were laid. Its characteristic sign was a mixture of the Byzantine and Roman liturgies. At first the newcomers probably used the Greek rite, but discovering that the Roman rite for the Mass was more widely known in Moravia, they adopted it, after translating it into the Slavonic tongue. [1] In many other respects, however, they followed eastern liturgical practices, and translations of holy books were also made from both Greek and Latin.

This happened at a time when the other European nations from the shores of Ireland to the Elbe, the Alps and the Adriatic were already Christians and had been, often for centuries, incorporated in the Latin and Roman cultural world. In those countries, only one language — Latin — which had nothing in common with their vernacular, was considered suitable for transmitting and developing the cultural treasures inherited from ancient and Christian Rome.

When the Slavs first came into contact with Christian culture in the ninth century, only the Anglo-Saxons had succeeded in securing for their native tongue a place second to the Latin. But they were situated far away from the valleys of the Morava and the Danube, where a Slavic political center was coming into being. King Alfred knew about the Moravians and, indeed, knowledge of this part of Europe seems to have been more extensive in Alfred’s England than it was in later days. But the Anglo-Saxon example could not inspire the Slavs any more than it impressed the recently converted Franks, Saxons and Germans, although the last named were converted by Anglo-Saxon missionaries. So overwhelming was the impact of Roman culture and memories upon the Franks that when Charlemagne decided to revive the glory that was Rome and adopt the imperial title, he deemed no language but Latin worthy of his renovated

1. It is possible that the brothers were familiar with a Greek version of the Roman liturgy known as the “Liturgy of St. Peter.” This Roman liturgy in the Greek translation seems to have been used in some places by the Eastern Church. Cf. below, p. 166.

![]()

86

Empire. Personally, Charlemagne was not averse to the use of the Frankish language; but his wholesale introduction of the Roman liturgy and customs and his infatuation with Roman traditions contributed most to the final victory of the Latin language, at the expense of the national languages and literatures. [1]

In the meantime, while the new Slavonic Church was being established in Moravia, the military and political clauses of the Moravo-Byzantine alliance came into operation. Louis the German was preparing a large-scale campaign against Rastislav and as this new adventure appeared to be of the first importance, he asked the blessing of the Pope Nicholas I. His new ally, Boris of Bulgaria, was requested to come to Tulin to discuss the details of the proposed campaign and of the alliance in general. But in spite of all these imposing preparations, Louis had to embark upon his campaign in 864 alone, and he waited in vain for Boris to launch his expected attack upon Moravia from the other side.

An explanation of this is to be found in the works of some Byzantine writers, who speak somewhat confusedly of an armed Byzantine intervention in Bulgaria in 864, which apparently took Boris completely by surprise. While preparing his own campaign against Moravia, he had to capitulate to the Byzantine forces. After this he promised to abandon the Frankish alliance and received baptism at the hands of Byzantine priests, and his country was placed under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch Photius. It was a great triumph for both the Byzantine Empire and the Church. The Byzantines were so anxious to detach the Bulgarians from the Franks that the Emperor gave his god-child, Boris-Michael, a small territorial concession as a baptismal present in 865.

1. The only instance in which the Anglo-Saxon example might have had some influence on the continent was the composition of the Saxon religious poem “Heliand.” But it would never have occurred to anybody in the West, not even to an Anglo-Saxon, to have his holy liturgy in the native tongue. The Franks, who fancied themselves as the heirs of the Romans, especially from Charlemagne’s time onwards, were the least tolerant in this respect. Cf. F. Dvornik, The National Churches and the Church Universal (London, 1945).

![]()

87

This Byzantine intervention against the Bulgarians probably saved the Moravian Empire from complete destruction. Rastislav was able to hold out against Louis the German only with the greatest difficulty and in the end he had to acknowledge Frankish supremacy in his lands. Had the Bulgarian threat materialized, Rastislav could scarcely have avoided utter extinction. Later in 866, when the son of Louis the German unsuccessfully rebelled against his father, Rastislav supported him.

The fight continued in the ecclesiastical field and was, indeed, no less fierce. The East Frankish bishops did not like the work which the Greek missionaries were so successfully carrying out in Moravia, and the Bishops of Regensburg and Passau, in particular, considered that their interests were being injured because their sees were the chief centers of propaganda in Moravia and Bohemia. Moreover, as has already been stated, the introduction of the Germanic custom of proprietary churches into the newly conquered lands made the conversion of pagans a very lucrative enterprise for the bishops and abbots who had become powerful landlords. A particularly busy evangelizing and colonizing activity was being directed in ancient Pannonia in the ninth century by Frankish bishops and barons. It was natural that the Frankish hierarchy should see a great danger to the expansion of its influence in the new missionary methods introduced into Moravia by Byzantine missionaries.

On the other hand, however, Pope Nicholas I had long watched with suspicion the growing ambitions of Salzburg and the other Bavarian sees. He was aware that an East Frankish or German Church was rising in the eastern part of the Carolingian Empire and that if it were allowed to assume great importance, it would prejudice the rights of the Roman See, as he conceived them.

Nicholas I (858-867) had a very high conception of papal supremacy. Under him the medieval Papacy emerged, for it was his letters and decrees which gave the medieval canonists the

![]()

88

material upon which they were to build the doctrines of the supremacy in all respects of the spiritual over the secular power.

This thesis, first developed by Gregory VII and his canonists in the eleventh century, was brought to fruition by Innocent III (1198-1216). It was defined in the most categorical terms by Boniface VIII (1294-1303) in his struggle with Philip the Fair, King of France. The whole evolution of the relations between the Church and the State in the Middle Ages was influenced by these theses of the canonists which were so fiercely opposed by secular lawyers at different periods.

It must be said that Nicholas I very greatly enhanced the ascendancy of the Papacy in the eyes of his contemporaries. He was, without doubt, a noble figure. Not only did he defend the indissolubility of Christian marriage against King Lothair of Lorraine with the greatest courage and perseverance, but he also tried to maintain complete control over all Christian Churches. He did not succeed in the East, where his attempts to intervene were unfortunately timed owing to his lack of knowledge of the actual situation and the successful opposition of the Patriarch Photius. Nicholas, however, registered complete success in the West, as the weakening of the Carolingian Empire after its partition in 817 greatly helped his efforts, and the Emperor Louis II (855-875), third successor of Charlemagne, proved to be a weak partner.

Thus Nicholas, having strengthened his authority over the Italian bishops, crushed every attempt of the West Frankish Church to obtain a degree of ecclesiastical autonomy. This is the real meaning of his struggle with Hincmar, Archbishop of Rheims. Nicholas once more claimed direct Roman jurisdiction over the whole area of the former province of Illyricum, which was in great part occupied by Slavs: Slovenes, Croats, Serbs and Bulgarians. He had to let the Franks send their missionaries to their pagan neighbors, but, while blessing their Christianizing activity, he was determined to seize the first opportunity to secure the direct submission of the newly converted peoples to the Roman See.

![]()

89

As will be shown in more detail, [1] Nicholas succeeded in supplanting Frankish missionaries in Bulgaria with priests sent from Rome and in subordinating Bulgaria, at least for the time being, directly to Roman jurisdiction. When all this is borne in mind, it can be understood that it was impossible for Nicholas to remain indifferent to the activities of Frankish and Byzantine missionaries in Moravia and Pannonia. It is therefore not surprising to learn from the biographers of Constantine-Cyril and Methodius that the Pope invited the Greek brothers to come to Rome.

It is not known in what circumstances this invitation was made, but Methodius’s biographer (Chap. VI) attributes the initiative to Nicholas I. Constantine’s biographer (Chap. XV), however, seems to indicate that the papal invitation reached the two brothers in Venice, after they had left Moravia "in order to have their disciples ordained.” [2]

There is nothing surprising in the brothers’ acceptance of the Pope’s invitation to visit Rome as at that time there was no animosity towards Rome in the East. Moreover, the two brothers were well aware that the Slavic lands where they had worked were a part of the patriarchate of Rome and it would have been only natural if they had intended to stop there — even if they were on their way to Constantinople.

On their way to Venice, the brothers registered another success: Kocel, the son of the Slavic Prince Pribina, who ruled in Pannonia under Frankish supremacy, had not only received the Greeks well as they passed through his country, but, preferring

1. See below. Chap. VI, p. 119.

2. It seems probable that the two brothers intended to return from Venice by sea to Constantinople in order to report to the Emperor and to the Patriarch on the result of their work and to have their disciples ordained. After receiving the invitation from Nicholas I, they changed their minds and went to Rome. It is, however, also quite possible that the Greek brothers intended to reach Constantinople by way of Rome. The fact that they had with them some of the relics believed to be those of Pope Clement I, the third successor of St. Peter, which they had discovered during their stay in Kherson in the Crimea during their mission to the Khazars, suggests this. They might have intended to leave the relics in Rome. We know that they left some of them in Kherson and others in Constantinople.

![]()

90

their method to that of the Franks, had given them about fifty young men to be instructed in Slavonic letters.

It was Nicholas’s successor, Hadrian II, who received them with every mark of goodwill in 868, approving their innovations and the Slavonic liturgy and himself ordaining their disciples. It was the Popes policy which explains his attitude towards the Greek missionaries; for after a short period of vacillation at the beginning of his reign, Hadrian followed very closely the policy of his energetic predecessor. As he also was determined to defend the rights of the Roman See among the newly converted peoples, it is not surprising that the Greek brothers from Moravia aroused such great interest on his part.

The concessions he made to the new Slavonic Church in Moravia — especially the solemn confirmation in a special bull, of the use of a Slavonic liturgy — were intended to weaken the influence of the Frankish Church. Constantine died unexpectedly in Rome on February 14, 869 (he became a monk on his deathbed and assumed the name of Cyril) and this seemed a serious setback to the Pope’s plans, [1] but when Kocel sent a special messenger to Rome requesting the Pope to join his territory to the new diocese planned for Moravia, Hadrian saw that the moment had come for speedy action. Methodius was therefore sent forthwith to Pannonia so that he might confer with the

1. According to Constantine’s biographer (Chap. XVIII) Methodius was determined to return to Constantinople with his brothers body. There might be some truth in this report, especially if we are authorized to surmise that both had intended to return to Byzantium via Rome. Methodius must have learned in the meantime of the political upheaval in Byzantium — the assassination of Michael III by Basil I and the replacement of Photius by Ignatius on the patriarchal throne. It is possible also that he wanted to return to his monastery in order to escape from such complications, or that he thought he needed a fresh authorization for his mission from the new regime. Kocel’s request seems to have made him change all such plans. F. Grivec’s monograph on Kocel (Slovenski knez Kocel, Ljubljana, 1938) was not available to me.

![]()

91

interested parties on the spot. When he returned to Rome to report, Hadrian decided to restore the ancient Metropolitan See of Sirmium (Srěm) for Methodius and to attach to his diocese not only Pannonia, but also the lands of the Moravian State. In 870 the news was received in Rome that the Bulgarians, who had accepted the jurisdiction of Rome in 866, had now returned to that of Byzantium. This fact may have influenced Hadrian’s decision.

In any case it was a very bold stroke and from the outset invited conflict with the rising Frankish-German Church. This new development caused the Bavarian bishops to abandon their ambitious and carefully laid plans, and when they learned of the Pope’s intentions, they protested by sending a memorandum to Louis the German, their King — and perhaps also to the Emperor Louis II. In spite of some distortion of historical facts, this document, entitled “The Conversion of the Caranthanians and Bavarians,” is very important for the study of the Christianization and colonization of the former Pannonia and Noricum.

Then, unfortunately, just as the Pope was sending out Methodius as Archbishop of Sirmium with the confirmation of all these unprecedented privileges, the political situation in Moravia suddenly changed and Louis the German became temporarily master of the whole country. Meanwhile Rastislav’s nephew Svatopluk, [1] impatient to become ruler of all these lands, made an alliance with the East Franks, who after deposing Rastislav blinded and imprisoned him in a Frankish monastery. Svatopluk had to acknowledge East Frankish supremacy and also became, for a time, a prisoner of Louis the German.

And so it happened that while Methodius was returning to take up his duties, he was arrested by Bavarian troops and tried by a local synod of sorts, presided over by the Archbishop of Salzburg, on charges of being an impostor and a usurper of episcopal rights. He was threatened by Hermanrich, Bishop of Passau, with being horse-whipped, and condemned to be locked

1. The old Slavonic form of his name was Sviętopl’k’. German chronicles called him Sventobold.

![]()

92

up in a Bavarian monastery. [1] Nicholas’s fear of the growing power of the Bavarian bishops was plainly not unfounded. Svatopluk appears to have been present at the synod, powerless to undo what his own mischief had created.

While Methodius was trying to send news of his plight to Rome, there was anxiety there about the result of his mission, and when Bishop Anno of Freising paid a visit to the Pope, he was asked for news of Archbishop Methodius. Bishop Anno replied that he had never heard of him, and it was not until three years later that Pope John VIII learned what had happened; he immediately despatched Paul, Bishop of Ancona, as a messenger to the Bavarian bishops and to King Louis the German, demanding the release of Methodius. The letters which the legate carried were couched in forceful terms; in the Pope’s opinion, the audacity shown by the Bavarian bishops out-topped the clouds, nay, heaven itself! If one were to weep over such tyrannical depravity, the Pope wrote to Hermanrich of Passau, all Jeremiah’s tears would not suffice. All the responsible bishops were temporarily suspended and severely lectured on canon law. King Louis the German and his Carloman were not spared either. It was stated that the rights of the Holy See were inalienable and that only the barbarian invasions had prevented Rome from claiming direct jurisdiction over Pannonia.

John VIII stood fast. He tried to contact Kocel directly and addressed an invitation to the Serbian Prince Mutimir, who ruled over what had been Moesia Inferior, to acknowledge the new Metropolitan See of Sirmium as reorganized for the new

1. H. W. Ziegler in his study "Der Slawenapostel Methodius im Schwabenlande” (Jahrbuch des Histor. Vereins Dillingen a.d.D. LII [1950], pp. 169-189) concludes that the Moravian archbishop was imprisoned in Ellwangen in the Black Forest. The synod was probably held in Freising. See F. Grivec’s “Quaestiones Cyrillo-Meth.” in Orient. Christ. Period. XVIII (1952), pp. 113-118, and S. Sakać’s "Bemerkungen,” ibid. XX (1954), pp. 175-180.

![]()

93

titular, the Greek Methodius. Only in one particular did the Pope make a concession to one of the main grievances of the Frankish bishops — he forbade the use of Slavonic in the liturgy. It may be that a copy of the memorandum addressed to Louis the German by the Bavarian episcopate in 870 had found its way to Rome. There this accusation may be read against Methodius:

"With his new-fangled philosophy and his recently invented Slavonic letters he undermines the Latin language, the Roman doctrine and the official Latin writing; he vilifies before the whole people [in Slavic countries] the Mass, the Gospel and the ecclesiastical office of the priests which [so far] they have celebrated in Latin.”

The words well express the Frankish clergy’s shocked bewilderment at this new method of missionary activity and illustrate the Latin complex that had developed since Charlemagne and was more characteristic of western and eastern Francia than of Rome itself. Making the concession did not greatly trouble the Pope so long as he could placate the Bavarians; but it was a matter in which Methodius could scarcely have been expected to concur. All his success among the Slavs was mainly due to the use of a Slavonic liturgy. So he paid no heed to the papal injunction and, together with his disciples, carried on as before in the interest of the Church. The legate himself may have seen the difficulty of acting otherwise, and Methodius hoped to explain the matter personally to the Pope before a definite decision was reached; for he was asked to report in person to Rome after two years, when the Pope proposed to make a final decision on the whole affair.

Methodius felt all the easier about it because the political situation in Moravia had altered again in his favor. The Moravians revolted against the Frankish nobles who were administering the territory during Svatopluk s exile in East Francia, and Svatopluk volunteered to placate the population. Instead, he joined hands with the rebels and under his leadership they annihilated the Bavarian army. He defeated every Frankish contingent sent against him and remained undisputed master of

![]()

94

the Moravian State. The Franks accepted the inevitable and signed a peace treaty in 874.

There followed a period of wide expansion. The Bohemian Duke Bořivoj and the Sorbs of modern Saxony joined the new Slavic federation. They were followed by the Slavs on the Vistula, whose capital was Cracow. The Vita Methodii states (Chap. XI) that the Archbishop tried in vain to convert “the mighty prince on the Vistula” and prophesied to him that he would be defeated, captured and baptized in a foreign land. The prophecy came true. This passage may justifiably be interpreted as a reference to Svatopluk’s conquest of the former White Croatia. So it came about that Svatopluk’s empire extended from the Elbe and the Saale to the upper Bug and the Styr, and in the east and south to the Tisza and the Danube — with fair prospects of annexing Pannonia.

A great Slavic empire — Constantine Porphyrogennetus called it “Great Moravia” —was thus in process of formation in the heart of Central Europe that seemed likely to absorb the other Slavic tribes to the north and south and to stop forever the progress of the Franks and the Germans towards the east. Its Slavic culture, rooted in Byzantium and combined with Western and Latin elements, gave it the essential condition of permanence and displayed in its Slavonic liturgy a mixture of Byzantine and Roman rites.

Why then did Svatopluk support Methodius only half-heartedly and show greater favor to the Frankish clergy? When Methodius was accused of disobedience and heretical teaching, he went to Rome, accompanied by a Latin priest named Wiching, who worked in Moravia and was a favorite of Svatopluk. There he cleared his character and the Pope proceeded with the organization of Methodius’s metropolitan diocese; but at this point an unfortunate concession had to be made to Svatopluk, who requested that Wiching be made the Bishop of Nitra. Methodius felt that this appointment would handicap his work; but in giving way he hoped to find a compensation in the fact that henceforward

![]()

95

accusations against him would cease and that the Pope would again approve the use of the Slavonic liturgy. [1]

Scholars have tried with little success to explain Svatopluk’s attitude towards Methodius. It is generally thought that Methodius upbraided Svatopluk over his private life; but whether true or not, this does not explain everything. The Greeks were as a rule excellent diplomats and always knew just how far they could go when dealing with potentates or princelings. There must have been some other reason, and it can probably be found in the different ways in which Greeks and Franks defined the rights of rulers over the churches they built.

To judge from the memorandum composed in 870 by the Bavarian bishops, the Germanic system of proprietary churches had prevailed in Pannonia. Frankish missionaries had also introduced this system into Moravia, and it was bound to appeal to a ruler of Svatopluk’s type. Greek missionaries certainly objected to it as being alien to their conception of canon law, and in this Methodius had the support of the Pope, since in the ninth century Rome did not know of any other system of ecclesiastical property other than that in force in the Eastern Church. This was conceived in the old Roman spirit, which in the eleventh century was to inspire Gregory VII during the Investiture contest with the Emperor Henry IV. It seems, then, that the ninth century witnessed in Moravia the prelude to the gigantic Investiture struggle which was to end so tragically in the disruption of Western Christianity at the Reformation. Things might have shaped differently had the Roman Church been able to keep the Slavonic Church under its immediate control, since it was free from this restriction of Germanic canon law, but with Svatopluk’s partiality for the Frankish system, this was not possible.

An additional reason explaining Svatopluk’s liking for German clergy and customs may be found in his political ambitions.

1. In his letter to Svatopluk the Pope writes: "It is not against the faith or against doctrine to sing the Mass in the Slavonic tongue, or to read the Holy Gospel or the divine lessons of the New or Old Testament well translated and interpreted, or to sing the other hours of the holy office."

![]()

96

Owing to his military success he added to his empire a major part of Frankish Pannonia. This fact and the declining power of the Carolingian dynasty in East Francia — modern Germany — may have emboldened him to plan to extend his domination over Bavaria, and even to replace the Carolingians in the eastern part of the Frankish Empire. He may have thought he had found in Wiching an able agent who would be helpful in the realization of his far-reaching political plans. Of course, the first condition for winning the support of the Bavarian clergy for his plans was to favor German customs and Latin liturgy in his lands.

Relying on Svatopluks favor, Wiching carried on his intrigues against the metropolitan and pretended that Methodius had sworn in Rome not to use the Slavonic tongue in the liturgy. Svatopluk was at a loss to know what to do; but Methodius appealed to the Pope for a formal denial of Wiching’s statement. This was granted and sent to Moravia.

The author of the Vita Methodii (Chap. XII) says that Methodius received an invitation from the Emperor Basil I to visit him in Constantinople. This invitation reached Methodius, according to the Vita, at a time when his adversaries were spreading rumors that “the Emperor was hostile to him and if he got hold of him, he would not escape alive.” It has been suggested [1] that this Byzantine animosity towards Methodius was caused by his partisanship for the Latins, and that because he obeyed the Pope, he was regarded as a traitor in Byzantium.

This interpretation ignores, however, the peaceful atmosphere which reigned between Byzantium and Rome after the reconciliation of the Patriarch Photius and the Pope in 880 — the rumors mentioned by the Vita are supposed to have circulated in Moravia after this date. [2] If the Byzantines surrendered Bulgaria in 880 to

1. See E. Honigmann, “Studies in Slavic Church History,” Byzantion XVII (1945), pp. 163-182.

2. See F. Dvornik, The Photian Schism, History and Legend (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1948), pp. 159-236.

![]()

97

Roman jurisdiction, how can it be asserted that they regarded Methodius as a traitor, since Constantinople had never made any serious claims to the land in which he worked?

Another theory has been advanced [1] in order to explain the feelings of hostility towards Methodius in Constantinople. Having been reinstated in the patriarchate, Ignatius is said to have ordained, after 870, another archbishop for Moravia in place of Methodius, who was a partisan of his rival Photius. This was Agathon whose name is mentioned in the Acts of the Council of Reconciliation of 880. This course not only was too dangerous for Ignatius, who had been reinstated by the help of the Pope, who was an ardent supporter of Methodius; he also appears to have accepted, for patriotic reasons, Photian clergy in Bulgaria, in spite of the condemnation of Photius and his followers by the Council of 869-870. Why then should he have ordained a rival prelate for distant Moravia?

Such initiative on the part of Ignatius could be explained only if the Moravians, after learning of Methodius’s disappearance, had asked Constantinople for another archbishop. In such a case Ignatius’s action would have no anti-papal or anti-Photian bias. When we take into consideration that in 870 Moravia was in the hands of Louis the German and governed by German counts — Svatopluk being held under surveillance in Bavaria — it is hardly conceivable that the Moravians could have taken such a step, unless we surmise that, in preparing a revolt against Louis the German, they had asked Byzantium for help. There is, however, no evidence for such a supposition.

1. See E. Honigmann, loc. cit. Honigmann s thesis that Agathon of Moravia is identical with Archbishop Agathon, member of a Byzantine embassy to Germany in 873, does not appear to be adequately demonstrated. It is true that Agathon of Moravia is listed among metropolitans and archbishops in the Acts of the Council of 880, but it is highly doubtful whether this may be taken as a proof of his higher ecclesiastical rank. In this respect the list is not reliable. Other bishops are mentioned among prelates of higher rank (e.g. the bishops of Apro, Keltzene, Ilion) and prelates of higher rank among bishops (e.g. the metropolitan of Neai Patrai, the archbishop of Arcadiopolis). It is better to remain on firmer ground and to regard Agathon as archbishop or bishop of Moravia in modern Serbia. See below, p. 164, for further details of this ecclesiastical foundation.

![]()

98

If there was any foundation for the spreading of rumors that the Emperor Basil I was hostile to Methodius, the latter’s attitude towards the Croats and the Pope’s attempt to extend Methodius’s jurisdiction over the territory of the Serbian Prince Mutimir — nominally subject to Byzantium — might have given Methodius’s enemies in Moravia the pretext for circulating rumors that he had lost the support of his countrymen.

In order to explain Methodius’s journey to Constantinople, which took place about the year 882, historians have often inferred that the persistent opposition of the Franks and Svatopluk’s vacillations forced Methodius to look to Byzantium for support. The authenticity of this report is simply denied by other historians, who were shocked by the idea that a man canonized by the Western Church should have had any dealings with the Patriarch Photius because, despite his reinstatement and reconciliation with Rome by the Council of 879-880, he had been re-excommunicated by the Pope.

But all these difficulties vanish if it is remembered that there never was any second excommunication of Photius. Once his true character has been established, there will be no objection to the historical validity of Methodius’ journey to Constantinople. But whether he travelled simply to visit his mother’s grave, or, more probably, to report to the Emperor and the Patriarch Photius, an intimate friend of his late brother Constantine-Cyril, who had given his blessing to the brothers’ missionary activities in Moravia, Methodius’s journey, undertaken in the peaceful atmosphere of reconciliation between Rome and Constantinople, could only promote the interests of Pope John VIII — a stout supporter of Methodius who had welcomed the reconciliation.

When it is recalled that Methodius’s diocese touched Bulgaria and perhaps even comprised a portion of the Serbian territory mentioned above, which was technically under Byzantine suzerainty, then the Moravian archbishop had every reason to go to Constantinople, whether at the Emperor’s invitation, as the legend has it, or even without it.

Basil I and the Patriarch Photius received Methodius cordially

![]()

99

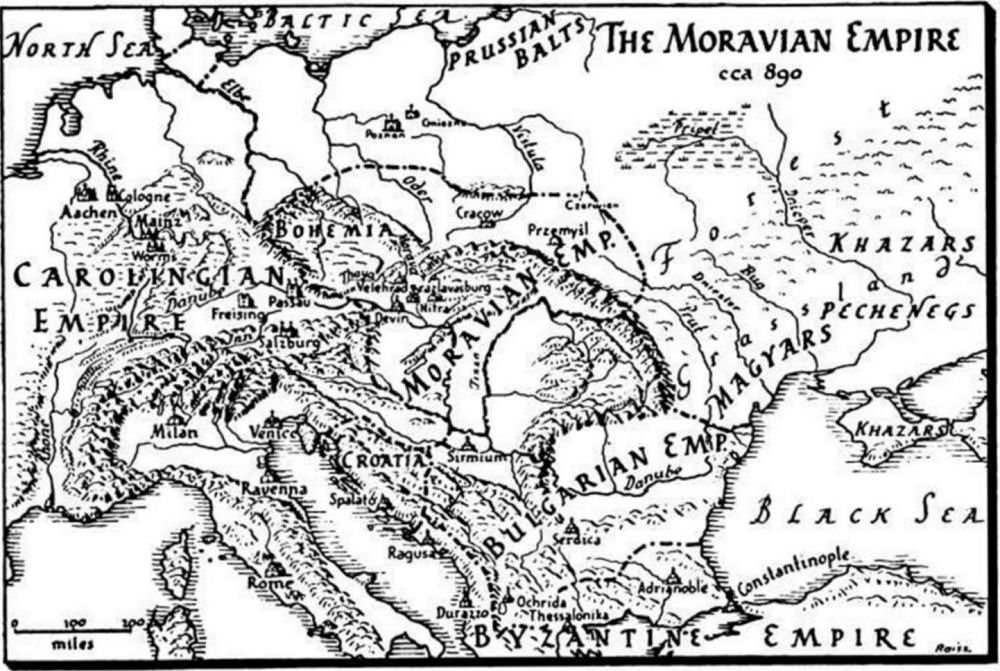

9. The Moravian Empire ca. 890

![]()

100

and he had the satisfaction of learning that his innovations in Moravia were approved by his fellow-countrymen, who manifested their intention to use them in the interest of their own Church. This is confirmed by the account of this incident in the Vita which states that at the Emperor’s request Methodius left a priest and a deacon behind in Constantinople with various Slavonic books. These formed the nucleus of a Slavonic center in the capital which may have been destined to supply the Bulgarians with Greek writings and Slavonic translations.

Byzantine support may have impressed Svatopluk, but it did not put a stop to the hostility of the Franks and their representative Wiching. The climax came in 884, the year of Methodius’s death (April 6, 884). As a precaution to ensure that his work would be perpetuated, he recommended as his successor his disciple Gorazd, a native of Moravia and one well schooled in Slavonic, Greek and Latin letters.

But before Gorazd had time to secure his succession, Wiching hastened to Rome where he produced some forged documents to convince Stephen VI that John VIII had forbidden Methodius to use Slavonic for the liturgy, that Methodius’s orthodoxy was suspect and that he had acted illegally in appointing his successor. Thereupon Wiching was made administrator of the metropolis, the use of the Slavonic liturgy was prohibited and Gorazd was summoned to Rome.

Wiching lost no time in getting his own way in Moravia, where Svatopluk, although surprised by the speed with which Rome had changed its attitude, placed him in charge of the diocese. Then, taking advantage of Svatopluk’s absence on a military expedition, Wiching proceeded to harass the favorite disciples of the late metropolitan. Those among them who were Byzantine subjects were either sold into slavery or exiled.

We learn from the Life of St. Naum that he was rescued from slavery by a representative of the Emperor Basil I in Venice, and the Life of St. Clement, a biography of another disciple, states that he was roughly handled by his military escort of German mercenaries. The exiles crossed the Danube and made for

![]()

101

Belgrade, which was then in Bulgarian hands, and were well received by Boris-Michael, Khagan of Bulgaria. Thus the work of the two Greek brothers was saved; for the Bulgarians handed on the fruits of their labors to the Serbs and the Russians. Other disciples of Methodius fled to Bohemia, possibly to Cracow and probably also to Dalmatia, where the Slavonic liturgy has survived to this day.

Later, things took a more hopeful turn in Moravia. On the outbreak of hostilities between the Moravians and the Franks, Svatopluk decided that he had had enough of Wichings intrigues and expelled him from the country. He realized too late the futility of his political ambitions in East Francia.

Svatopluk’s premature death changed the whole situation, however, and his successor, Mojmír II, had to defend his rights against the claims of his two brothers. The Franks took advantage of this state of affairs to weaken their dangerous neighbor. They succeeded also in winning over the Czechs and the Sorbs, who made peace with them and recognized their supremacy. The Moravian Empire, exhausted by the struggles, thus found itself much reduced in size, but Mojmir II, who eventually defeated his brothers, proved to be an able ruler. His first preoccupation was to reorganize the Church in his country. When he applied to Rome for bishops, John IX sent a legate to consecrate a new hierarchy in Moravia, with results which are not known for certain.

In 906 the Germans called upon the Magyars to help them to destroy this rising power in Central Europe and the invaders swept into Moravia through the Carpathian passes. Mojmir II fell in battle and his capital was so thoroughly destroyed that its very site is still a topic of debate. It does seem, however, that a few bishops in Cracow and modern Slovakia were able to survive the catastrophe.

Such was the end of a noteworthy attempt to set up a political and cultural power in Central Europe; but the disaster left its mark upon the subsequent history of the whole continent. What Europe needed at the time was direct contact with Byzantium,

![]()

102

the storehouse of Greek and Hellenistic culture. Access by sea had been almost cut off by the Arabs; but the Danube valley and the Balkans were kept open by the Moravians and the Greeks so that Roman and Byzantine cultures could meet in Central Europe. Had this situation lasted, Western Europe would have evolved along different lines. But the opportunity was lost and centuries were to elapse before the treasures of Constantinople were re-discovered in circumstances which were not so happy.