5. After the Destruction of the Moravian Empire. Germany and the Rise of Bohemia and Poland

1. Consequences of the Moravian catastrophe

3. Bohemia, Bavaria and the new Saxon dynasty

4. The first wave of the “Drang nach Osten”; St. Wenceslas of Bohemia

5. Otto II, the Magyars and the Slavs

6. Mieszko I of Poland, Boleslas I of Bohemia

7. St. Adalbert, Bishop of Prague; Poland and the struggle between the two Bohemian dynasties

The Moravian catastrophe proved to be an important turning point in the evolution of the Slavs and in the history of Central Europe. A new foreign element had appeared in the Danube basin and separated the Western from the Southern Slavs, who now had to adapt themselves to a new situation and find fresh outlets in their political and cultural life.

What were the immediate effects of the destruction of Moravia on those Slavs who had been incorporated in the Moravian Empire? It seems that the Magyars limited themselves to wiping out the center of Moravian power in the valley of the Morava and in the territory between the river Dyje (Thaja) and the Danube. After the archaeological discoveries recently made at Staré Město, there can now be little doubt that one of the main centers of Moravian power — perhaps the fortress which had astonished the writer of the Annals of Fulda — lay in the valley of the lower Morava. This center was completely destroyed at this time and a similar fate befell other Moravian fortified settlements. But in Slovakia the Magyars seem to have done no more than subjugate the native population. We learn from the Annals of Sázava, the Czech abbey of the Slavonic rite,

![]()

104

that in the eleventh century the Slavonic monks expelled from this Abbey took refuge in Hungary. This evidence shows that priests of the Slavonic rite must have survived the Magyar invasion and that Christian settlements continued to exist in Slovakia and perhaps also in Pannonia. This was due to the fact that the victorious nomads were not interested in the mountainous regions and they needed the agricultural products of the natives. There is evidence which strongly suggests that a most important Christian and Slav center existed in Esztergom (Ostěrgom’) on the middle Danube and it was from there that the Christianization of the Magyars started in the tenth century. Other similar centers, it seems, continued to exist, and in the eleventh century they formed a bridge between Bohemia (with its surviving Slavonic clergy), Kievan Russia and the Croats.

In the other parts of the former Moravian Empire, Cracow and the rest of former White Croatia were most probably spared. This region may have recognized a kind of Magyar overlordship; at least it appears to have lived on friendly terms with them. Constantine Porphyrogennetus, in his report on the White Croats, asserts that their prince made a “matrimonial alliance and friendly treaties with the Turks,” i.e. with the Magyars. As will be shown, the Slavonic liturgy survived in Cracow and this city may also have become the refuge of two Moravian bishops who had survived the destruction of their metropolis.

Bohemia and White Serbia had both drifted away from the Moravian Empire, torn as it was by dissensions between Svatopluk s successor, Mojmír II, and his brothers. The only course open to them now was to accept the overlordship of the Franks. The Armais of Fulda report that after the death of Svatopluk the Sorbs sent a mission to Arnulf to assure him of their loyalty, thus signifying the submission of White Serbia. The same annalist further reports that in 895 two Czech Dukes, Spytihněv and Witizla (Vitěslav), accompanied by numerous

![]()

105

nobles, appeared at the Reichstag of Regensburg where they were received with full honors by King Arnulf and with the customary handshake renewed their allegiance to the Frankish Empire as represented by the Duchy of Bavaria.

The fact that two dukes are specially mentioned indicates that Bohemia was divided into two dukedoms, which coincides with what we know from other sources about ancient Bohemia. The presence of Croats in eastern Bohemia is attested by King Alfred and by the foundation charter of the bishopric of Prague. On the other hand, an old Czech tradition attributes the foundation of the Czech dynasty to Přemysl. Bořivoj, the first known Christian Duke of Bohemia, who was baptized by St. Methodius, governed the western part of Bohemia including Prague. It is probable that eastern Bohemia was annexed by Svatopluk of Moravia when he conquered the whole of White Croatia, which included that region. The western dukedom became part of Moravia after the submission of Bořivoj and the short symbiosis of the two parts of Bohemia within a common empire appears to have brought them close together. The Bohemian Croats joined the Přemyslide part of Bohemia and from 895 onwards the two dukedoms remained closely allied. At the Reichstag of Regensburg, Spytihněv represented the Přemyslide part of Bohemia and Witizla (Vitěslav) that of the Croats. Vitëslav’s dynasty is known in history as the dynasty of Slavnik, after the best known member of this family. The subjection of other tribes in Bohemia was concluded by both dukedoms at the beginning of the tenth century.

The common Magyar danger naturally drew Bohemia and Bavaria closer together. Spytihněv s successor, Vratislav (915920/21), probably died while defending his country against a Magyar invasion. He was succeeded by his son Wenceslas I (920-929), who was still a minor, and so the regency was exercised by his mother Drahomira. She, however, found her authority undermined by her mother-in-law Ludmila, a very pious lady

![]()

100

who had great influence with the young Duke. So, Drahomira, counting on the support of a semi-pagan reaction, had her put to death, but the Christian party overthrew the mother and proclaimed the young Wenceslas as reigning prince.

So it happened that the Czechs acquired their first martyr, St. Ludmila, a circumstance of great importance, because it impressed on their German neighbors that they were good Christians. The Duke of Bavaria was one of the first to learn about the new Saint and, afraid that the change on the throne might also mean a change in the attitude of the Czechs towards Bavaria, he made a journey to Bohemia. There he was assured by the young Duke that everything would remain unaltered. To placate the Bavarian Duke, Wenceslas even promised to dedicate the cathedral he proposed to build in Prague to St. Emmeram, patron saint of Bavaria and of Regensburg, to which Bohemia was now ecclesiastically subordinated.

It is interesting to note that in spite of this promise, which is attested by the Slavonic legend of St. Wenceslas, the Duke actually dedicated the new cathedral to St. Vitus (Guy), patron saint of Saxony.

This substitution of one patron saint for another was symbolic of a very important political change which Germany, formerly East Francia, had meanwhile undergone. After the extinction of the eastern branch of the Carolingian dynasty, the German Dukes, faced by the constant Magyar danger, decided to elect a king. After the death of Conrad of Franconia in 919, Henry the Fowler, Duke of Saxony, the most outstanding duke in Germany, became king. This year marked the birth of medieval Germany. Bavaria, which was certainly more civilized than Saxony, also claimed the leadership of the German nation, or Regnum Teutonicorum, as it was already called in this period, and Henry had great difficulty in getting Arnulf of Bavaria to acknowledge his royal authority. As a result, the Saxons were determined to undermine the position of Bavaria in Germany as much as possible. It seems probable, therefore, that, in his determination to weaken the influence of Bavaria, Henry I tried to supersede it in Bohemia.

![]()

107

He succeeded only too well; for Wenceslas and his counsellors, preferring to have as their overlord a distant Saxon instead of a nearby Bavarian, transferred their allegiance to the King and Duke of Saxony. This was the beginning of the decline of Bavarian influence in Germany. The later course of events shows that it would have been better for Germany and for Europe as a whole if Bavaria, which was more cultured and nearer to the West, had assumed the leadership in the Regnum Teutonicorum. For it was from Saxony that the "Drang nach Osten” started — the push towards the East which ultimately produced Prussia and the Prussian spirit of domination.

Henry I initiated this new policy of eastward expansion which Germany was to pursue for the next thousand years and which culminated in 1942 on the Volga river. After successfully stemming the terrible invasions of the Magyars and completing the military organization of Saxony and Thuringia, Henry I launched the first big Saxon drive beyond the Elbe in the winter of 928. His army crossed the Elbe and the frozen marshes of the Havel river and took Brunabor, the principal town of the Havelians. Thus the foundation stone of the history of Brandenburg was laid and Brunabor became the first important milestone in the German drive towards the East. There followed the submission of the Veletians (Ljutici or Vilci), who had to promise to pay tribute. The same fate overtook the Obodrites and marked the beginning of the history of modern Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg.

The triumphal march of the Saxon armies through Slavic territories ended, probably in the spring of 929, with the subjugation of the Sorbian tribes between the Saale and the Elbe rivers, and on the site of Jahna, the conquered capital of the Daleminci, the new city of Meissen was founded to become the second important Saxon outpost.

It was believed by historians that these victories over the

![]()

108

Polabian Slavs were crowned by the conquest of Bohemia, then ruled by Wenceslas; but in fact Wenceslas remained loyal to Henry I throughout his life, as is attested by his biographer Christian, and by the chronicler Thietmar. The murder of Wenceslas by over-zealous followers of his brother Boleslas cannot be invoked as a proof that his pro-Saxon policy was resented by the Czechs. His murder and the change on the ducal throne of Prague were the results of internal strife and domestic jealousy. Wenceslas led a pious life, and seems to have married only under pressure from his counsellors; but having produced an heir, he separated from his spouse, devoting himself to works of piety. This and the growing influence of the clergy on public affairs were resented by many, and the party of opposition to Wenceslas s religious policy was lucky enough to enlist the support of his brother, the energetic and ambitious Boleslas.

Henry I, it is true, was alarmed by the change in Prague and, accompanied by Arnulf of Bavaria, he made an appearance in Bohemia. The King and the Duke soon realized, however, that Boleslas had no intention of altering his country’s policy towards Germany and, as the Saxon chronicler Widukind has it: “He remained faithful and useful to the Emperor as long as he [Henry I] lived.”

The reorganization of the subjugated countries in the East was accomplished by Henry’s son, Otto I (936-973), who concentrated his attention on the region between the Saale and the Elbe, as it was an important link between Saxony, Bavaria and Bohemia. He extended to this country the military system, invented by his father, of fortified castles at strategic points and entrusted its government to the notorious count Gero, whose ruthless methods extended German power as far as the rivers Neisse and Bober. Gero was long remembered by the Slavs and his deeds earned him a place in the most famous German heroic epic, the Nibelungenlied. After Geros death (965) Otto I divided the territory into several marks, including Ostmark,

![]()

109

Lausitz and Meissen, and undertook the Christianization of the newly conquered Slavic territories. Instead of repeating the old missionary methods, he started founding bishoprics — Oldenburg, Havelberg, Brandenburg, Merseburg, Zeitz and Meissen — which became the seats of German bishops, following in the spirit of the German ecclesiastical system. All Slavic lands, according to Otto’s grandiose plan, were to be under the new metropolis, Magdeburg, his own favorite foundation. Pope John XII accepted this idea in 962 and gave Otto the right to establish bishoprics in all Slavic territories, as and where it seemed expedient.

So it appeared that German political and ecclesiastical supremacy over all Slavic lands east of the Elbe was firmly established; but very soon two new and important factors began to retard German political and cultural penetration — the Bohemia of Boleslas I and Poland.

There is some evidence to show that Boleslas had difficulty in dealing with Otto I at the beginning of the latter’s reign, probably because one of Boleslas’s vassals had tried, unsuccessfully, to transfer his allegiance to Otto. But this dispute was settled amicably and henceforth Boleslas continued to recognize the overlordship of the Saxon. With his contingent of troops he took part in the famous battle on the Lechfeld (955) in which Otto I finally crushed the military might of the Magyars, forcing them to settle down to a more peaceful life. Boleslas not only occupied Moravia, which at that time still included the whole of modern Slovakia, but also Silesia and the rest of the former White Croatia including Cracow, and it looked as though Bohemia would become the heir of Great Moravia. This idea certainly inspired Boleslas and was not objected to by Otto I, because both Bohemian Dukes owed allegiance to him not only as Emperor (from 962 onwards) and head of western Christendom, but also as King of Germany.

It was only to be expected that this new version of the Moravian Empire would try to expand towards the north into the former White Serbia.

![]()

110

The other important factor emerging at this period was the Polish Duke Mieszko I. He is introduced into the annals of history by the chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg and by the contemporary Arab writer Ibn Jakub. According to these two authors, Mieszko — of the dynasty founded by Piast — was a mighty ruler commanding a standing army of 3,000 men whom he paid in minted money. He appears to have been master of a strong federation of Slavic tribes known since then as Poles (Polane) after the most powerful among them, and the center of his realm was Gniezno (Gnesen).

The sudden appearance of a powerful Slavic prince on the political scene of Central Europe about the middle of the tenth century has mystified many historians and, to solve this difficulty, they invented the theory that Mieszko was a Scandinavian Viking who had imposed his rule on the Slavs on the Oder and the Vistula. There is no evidence whatsoever for the view that the Piast dynasty was of a non-Slav origin. If it is recalled that Mieszko ruled over the territory which may have been the center of the primitive habitat of the Slavs — or which, at least, was in Slavic possession from after 500 B.C. — then the appearance in the tenth century of a powerful confederation in these regions ceases to be mysterious. Mieszko s state was the result of a long evolution under the leadership of an energetic Slav dynasty, an evolution which remained unrecorded because there was no chronicler to record it for posterity.

When the first Polish duke attested by history appeared on the political scene, he was about to annex the Pomeranian Slavs to his own state. Observing that the Germans also had their eyes upon this region, especially its western part including Stettin (Sczeczyn), Mieszko made a rather clever deal with Gero in 963, and in order to avoid complications with the Germans, Mieszko promised to hold the western part of Pomerania with Stettin, which he was about to conquer, as a fief of the Empire. It was an ingenious move, which allowed Mieszko to complete

![]()

111

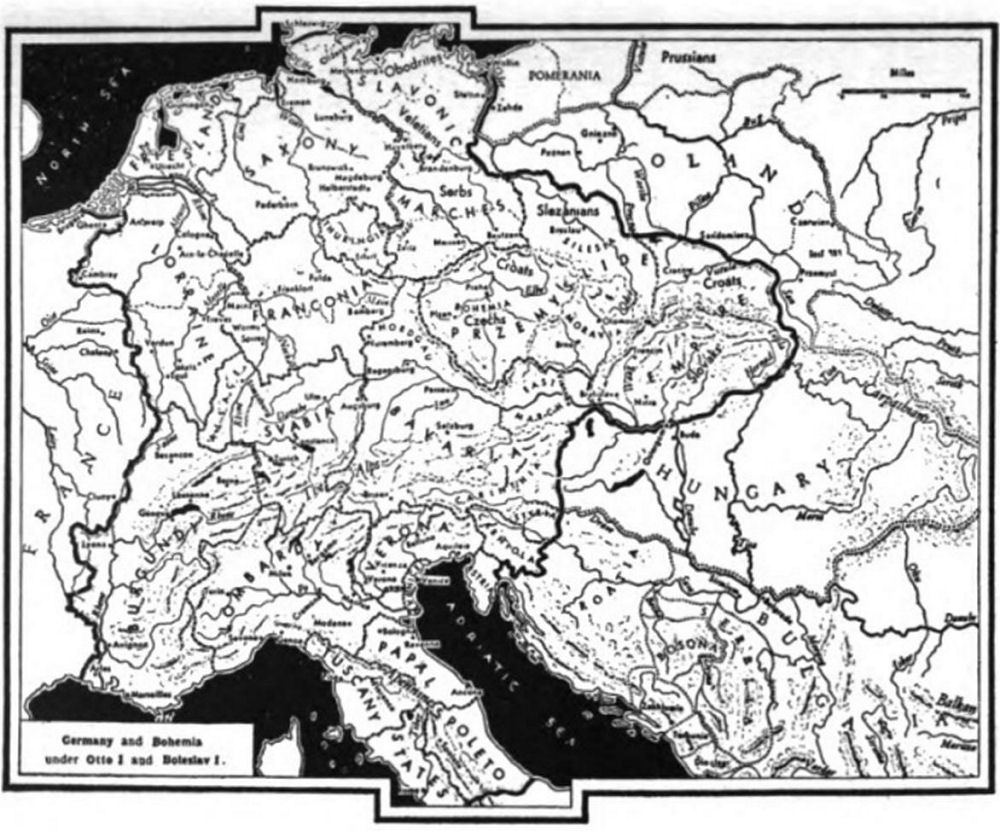

10. Germany and Bohemia under Otto I and Boleslav I

![]()

112

his conquest of western Pomerania without coming into conflict with the Germans. There is no evidence that Mieszko declared his whole country to be a fief of the Empire, nor was there any need for this.

But Otto’s plans for Magdeburg and the Christianization of the Polabian and Baltic Slavs had opened Mieszko s eyes to another danger. He saw that it was necessary for him and his country to become Christian and to remove forever any danger of German intervention in his lands under the plea of spreading the Christian faith. Once again he made a clever move, turning not to Otto I but to Boleslas I, the Christian Duke of Bohemia. Boleslas gave Mieszko his daughter Dubravka in marriage and sent him the first Christian missionaries.

The Bohemian and Polish Dukes went even further and, probably in 966, addressed to Pope John XIII (965-972) a request that they might establish bishoprics in their countries. It was again a request which Otto could not oppose. So it came about that the Polish bishopric of Poznań (Posen) was founded about 968 and was made directly subject to Rome and not to Magdeburg. The bishopric of Prague did not come into being until 973. Otto did not oppose its foundation, but in order to gain more influence over Boleslas II, who succeeded his father in 967, he created two bishoprics, one for Prague and one for Moravia, reserving for himself the investiture of both bishops. And, again continuing the policy of his father, he subordinated the Czech bishoprics not to Salzburg, the Bavarian metropolis, but to Mainz.

So it happened that Otto’s ingenious project of making Magdeburg the metropolitan see for the whole of the Slavic East could be only partially realized. Owing to further developments in the lands between the Elbe and the Oder, however, Otto’s ecclesiastical foundations became almost a dead letter for at least two centuries. When in 983 the news reached the Elbe that Otto II, who had succeeded his father in 973, had been defeated by the Arabs in Calabria and had died, all the newly conquered Slavs between the Elbe, the Oder and the Baltic rose against the

![]()

113

Germans and their God. Hamburg was captured, Havelberg sacked, Zeitz razed to the ground, and Brandenburg destroyed. When the tornado of this bloody revolt had passed, the Germans held only Holstein in the north and the lands of the Sorbs, and the whole work of Christianization was undone. New ways had, therefore, to be found and this task fell upon the young Emperor Otto III.

Another change of great consequence was brought about by Mieszko in the east. After consolidating his position among the Pomeranians and the tribes on the Oder and the Vistula, Mieszko began to annex the Slavic tribes of ancient White Croatia. He seems to have occupied after the defeat of the Magyars what is today Eastern Galicia, the Red cities and Přemysl, and his growing power attracted the Slavs of Silesia and of the Cracow region and impressed even the Slavniks, whose country had long ago belonged to White Croatia. Boleslas II proved less competent than his father, and seizing his opportunity, Mieszko annexed Silesia and the region of Cracow.

Thus at the end of the tenth century there emerged in Eastern Europe a mighty Slavic state which was bound soon to expand to other Slavic lands, and Otto II, engrossed in difficulties in Italy, could not intervene to change the situation. To ensure for himself the protection of the Papacy, the greatest spiritual power in Europe, Mieszko I dedicated the whole of his kingdom, from Stettin to Gdansk and from Gnesen to Cracow, to the Holy See before his death in 992. It was a clever move and Mieszko thereby initiated a tradition which was to be followed by Poland for many centuries to come.

The results of the rise of Poland were inevitably felt in Bohemia. That country, as has been mentioned, was divided into two dukedoms united by free consent of the two ducal families — the Přemyslides and the Slavniks. At first this partnership was very successful and the cooperation between Boleslas I and

![]()

114

Slavnik led to the conquest of Moravia, Silesia and the region of Cracow. This agreement continued to operate when Boleslas II succeeded his father in Prague. The first Czech bishop of Prague, after the death of the German Dietmar, was a member of the Slavnik family, Adalbert-Vojtěch, who had been educated at Magdeburg. Adalbert was a saintly man and zealous in the missionary work of his large diocese and, owing to his intervention, the Pope consented to the suppression of the bishopric of Moravia after the death of Vracen, the only known titulary. This fulfilled an old dream of Boleslas II, who wanted the realm which he administered in association with the Slavniks to be subjected to a single bishop residing in Prague.

This peaceful collaboration between the two leading families of Bohemia was disturbed after the Polish conquest of Silesia and Cracow. When Boleslas II declared his intention of attacking the Poles to win back the lost territories, he was opposed by Soběslav, the reigning duke of the Slavnik dynasty, Adalbert’s brother. This first disagreement between the two Dukes cost Adalbert the support of Boleslas II and, realising that the break between his brother and the Duke of Prague made it impossible for a Slavnik to administer the Czech Church successfully, Adalbert left Prague, intending to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The Abbot of Monte Cassino, where he stopped on his way, dissuaded him from his plan, arguing that it .vas not by pilgrimages but by leading a saintly life that salvation was to be won. Adalbert then resolved to enter the Greek monastery founded by St. Nilus, but in the end he became a monk in the Abbey of SS. Alexius and Boniface in Rome.

Boleslas II attacked the Poles but, lacking the support of the Slavniks, he was defeated. His prestige sank very low and he saw that the only way out of his difficulties lay in a reconciliation with his former allies. Their first condition, of course, was the restoration of the See of Prague to Adalbert, who consented reluctantly to return in 992. But this agreement lasted for only three years. New difficulties arose and Adalbert left Prague again; for it was evident that the Slavniks preferred to be allied

![]()

115

with the Poles rather than with the Přemyslides. Boleslas II, who lacked his fathers diplomatic talent, foresaw that the defection of the Slavniks would probably entail the loss of Moravia and modern Slovakia, and in desperation he decided to follow the advice of his counsellors and rid himself of the whole rival dynasty by assassination. In 995, when the Slavnik Duke Soběslav was in Germany with his army helping the Emperor to subdue a new revolt of the Slavs, Boleslas II, in spite of his promise not to take any action inimical to the Slavniks during the Duke’s absence, treacherously attacked Libice, the main castle of the Slavniks, and massacred all its inhabitants, man, woman and child. This bloody act united the whole of Bohemia under the exclusive rule of the Přemyslides. Soběslav was unable to undo what had been done and took refuge with his troops in Poland. The new Polish Duke Boleslas the Great, called Chrobry (The Brave) by the Poles, welcomed him and together they awaited an opportunity for revenge against Prague.