6. The Southern Slavs, the Franks, Byzantium and Rome

1. Slow Hellenization of the Slavs in Greece

3. Byzantium, the Franks, the Papacy, Serbs and Croats

4. Political aspirations of Symeon the Great of Bulgaria

6. The Bogomils and the disintegration of Bulgarian power

7. End of the first Bulgarian Empire

While these states were emerging among the Western Slavs, other developments were ensuing among those Slavs who had penetrated into Greece, those who had mingled with the Bulgars and the Croats, and among the Slavs of modern Serbia.

The political and military weakness of Byzantium in the seventh century, when the Empire was attacked by the Persians and then by the Arabs, had given the Slavs the opportunity to settle permanently in the former province of Illyricum and in Dalmatia, and also to penetrate deeply into the interior of Greece. [1] Later the situation improved owing to the reforms introduced by the Emperor Heraclius (610-641) and brought to their full effect by the iconoclastic emperors of the Isaurian dynasty

1. On the Slavs in Greece, see the most up-to-date study by M. Vasmer “Die Slaven in Griechenland” (Abhandl. d. Preuss. Akademie, Phil.-hist. Kl., Berlin, 1941). The author gives useful bibliographical notices on the subject and analyzes in an unbiased way the Slavic place names in Greece and on the islands which testify to the presence of the Slavs in those places for some time after the Slavic invasions.

On the great victory won by Justinian II in 688 over the Slavs in Greece, see the study by A. A. Vasiliev, “L’entrée triomphale de l’empereur Justinien II à Thessalonique en 688,” in Orientalia Christiana periodica XIII (1947), pp. 355-368. This Byzantine success was decisive for the further evolution of Greece. Justinian II also transported a great number of captive Slavs to Asia Minor where they formed an important military colony.

![]()

117

(717-780). The whole Empire was divided into themes, each governed by a strategos, in whose hands all civil authority and military command were vested. The Empire was, of course, deprived of its eastern possessions, which were occupied by the Arabs, but it retained a firm hold on Asia Minor, the center of its economic and military resources. The position of the Empire in Macedonia, Greece and the Peloponnese was considerably strengthened during the eighth and the first part of the ninth centuries. The Slavs in Macedonia and Greece were successfully brought to heel in 783 under Constantine VI (780-797), and Irene (797-502) crushed a Slavic revolt in Greece, thereby influencing the complete Hellenization of the Slavs of this part of the Empire. The Hellenization of the Slavs in the Peloponnese started at the beginning of the ninth century, when an attempt by them to besiege Patras was frustrated after 805. Hellenization here, however, took much longer than it had in Greece, and important Slavic settlements could be found in the region of the Taygetus Mountains as late as the fifteenth century. [1]

The Christianization and Hellenization of the Slavs in Macedonia, Thrace and Epirus — at least in those parts of these provinces which remained under Byzantine rule — were pressed on with vigor during the first half of the ninth century, and it is interesting to follow the different stages of the ecclesiastical reorganization of those regions after Christianity had been utterly destroyed there. This meritorious activity of the Byzantine Church reaped its best harvest under the Patriarch Photius.

1. For the Slavs in the Peloponnese see the recent study by A. Bon, Le Péloponnèse byzantin jusqu’en 1204 (Paris, 1951), pp. 27-74; cf. also P. Charanis, "The Chronicle of Monembasia and the Question of the Slavonie Settlements in Greece,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers V, 1950. Several problems concerning Slavic settlements in Greece are still debated as is shown by the controversy about the capture of Corinth: cf.

Kenneth M. Setton, ’The Bulgars in the Balkans and the Occupation of Corinth in the Seventh Century,” Speculum XXV (1950), pp. 502-543;

P. Charanis, "On the Capture of Corinth by the Onogurs and its Recapture by the Byzantines,” ibid. XXVII (1952), pp. 343-350;

Kenneth M. Setton, "The Emperor Constance II and the Capture of Corinth by the Onogur Bulgars,” ibid., pp. 351-362.

![]()

118

But the growing influence of the Roman See under Nicholas I was felt at an early date even in the Balkans. This territory formed the major part of the old Roman province of Illyricum, which up to the year 731 was ecclesiastically directly subject to the Roman See. Leo III, the first iconoclastic emperor, detached Illyricum from the jurisdiction of Rome and subordinated it to the patriarch of Constantinople, and although the decrees against the worship of images issued by the Emperor and his iconoclastic, successors were later rescinded, the Byzantines refused to return this territory to the direct jurisdiction of Rome. Nicholas I made fresh and energetic attempts to regain at least the jurisdiction over the Slavic population of the former Illyricum, but as has been shown, the Franks were also anxious to extend their political and religious influence over the new Slavic states which were rising in the Balkans, and Bulgaria was the land where the interests of these three powers clashed most vehemently.

Thanks to their alliance with Great Moravia, the Byzantines were able to effect a military and cultural encirclement of Bulgaria and force Malamir’s successor, Boris (852-889), to enter the cultural sphere of Byzantium. This was a great success; for it put a stop to Frankish penetration into the Balkans. But complications soon arose. The first Christian khagan of the Bulgarians, Boris-Michael, was an astute ruler who perceived very quickly that there was a chance for him to profit from the competition between the Byzantines and the Franks for influence in Bulgaria, and also that the interest which was being shown in his country by the Papacy, a new power in the West, could eventually be turned to his own advantage.

He accepted Byzantine religious supremacy; but he was very jealous of his own influence over the Church and disliked the leading part which the Byzantines were playing in the religious affairs of Bulgaria. Desiring more independence, he asked the Byzantines to give him a Patriarch, but all he received in reply

![]()

119

(in 865) was a beautifully written and lengthy screed from Photius explaining all the most important doctrines of the Church and containing a list of the names of all the heretics who had been condemned by the holy councils in the past centuries. This was accompanied by a treatise on the duties of a Christian ruler. Boris, whose way of life was primitive and simple, did not appreciate all these platitudes, and Greek dialectics were more than his untutored intelligence could grasp. He therefore decided to ask the Pope for a patriarch and the Franks for missionaries.

This request from the Bulgarian ruler caused great rejoicing in Rome. Nicholas I seized this opportunity of bringing Bulgaria completely under Roman influence. With perfect understanding of the simple Bulgarian mind, he lost no time in sending Boris a letter, which still remains a masterpiece of psychology and pastoral theology. At the same time, he sent to Bulgaria two bishops and a number of missionaries with the object of forestalling the Franks.

Nicholas’s initiative was crowned with success. Boris was so delighted to have found someone who explained to him that the Bulgarians did not commit mortal sin by wearing their trousers even after baptism — for such were the problems that troubled the primitive Bulgarian Christians — that he dismissed not only the Greek missionaries but also some Franks who had arrived in response to his own invitation. Thus, the former province of Illyricum, which could have become the bridgehead connecting West and East, became instead the battlefield of two Churches.

This Roman success naturally provoked the greatest indignation in Constantinople. The Byzantines, however, had their day in 870 when Boris, disappointed by the Pope’s refusal to give him a patriarch or at least an archbishop of his own choosing, turned again to the East and accepted bishops and priests from Byzantium. Then Ignatius, who became Patriarch after the removal of Photius, is said to have sent an archbishop and some bishops to Bulgaria.

So in 880, Bulgaria became once more the object of bargaining

![]()

120

between Rome and Byzantium when, after Ignatius’ death Pope John VIII succeeded in coming to an understanding with the new Patriarch Photius and then it was agreed that Bulgaria was to be left to Roman jurisdiction. This was the price which Byzantium had to pay for the Roman See’s recognition of Photius as a legitimate Patriarch.

So greatly did the Byzantines value reconciliation with Rome that they accepted this condition and the Patriarch Photius surrendered jurisdiction over Bulgaria. [1] It seems, however, that he asked Rome to leave the Greek priests there and not to replace them by Latin clergy, as had happened when Nicholas gained his temporary foothold in Bulgaria.

Contrary to the opinion of most historians of this period, this arrangement was a perfectly sincere one. There was no attempt on the part of the Byzantines to deceive Rome nor was there any re-excommunication of Photius by the Roman See. Thenceforward, until the eleventh century, peace reigned between the two Churches which had formerly quarrelled so bitterly over the jurisdiction of this part of ancient Illyricum. Nevertheless, Bulgaria did not return to Rome.

The explanation of this is to be found in the policy followed by the Khagan Boris-Michael for a number of years. This primitive but astute ruler perceived that the rivalry between Rome and Byzantium offered him his best chance of securing ecclesiastical independence for his country. He cleverly evaded all the invitations from the Pope to send an embassy to Rome to settle the details of the new agreement by which the Roman supremacy was recognized. He neither refused nor accepted anything but simply thanked the Pope for his solicitude, assured him that he and his people were in good health and expressed the cordial hope that all was well in Rome. At the same time he retained

1. This concession was all the more important because the Bulgarian State comprised not only a great part of Macedonia, which belonged to Illyricum, but also a part of Thrace, which was outside this province and under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople. This problem is treated in F. Dvornik, The Photian Schism, History and Legend (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1949), pp. 210 ff.

![]()

121

the Greek bishops and kept them very much under his control.

Thus the quarrel between Rome and Byzantium over ancient Illyricum laid the foundations of the first national Church to arise among the peoples who had only recently been converted to Christianity. It is permissible to surmise that the Greek clergy rather encouraged Boris-Michael in his attitude of compromise. Then he was greatly favored by fortune; for Pope John VIII died and a rapid succession of three other Popes between 882 and 885 prevented any further Roman intervention in Bulgaria.

The year 885 presented Boris with another unexpected opportunity. As has been seen, [1] many of the most prominent disciples of Archbishop Methodius took refuge in Bulgaria when they were driven from Moravia, and Boris readily realized that the Slavonic alphabet and liturgy which they offered could be of great value to him in completing his ecclesiastical scheme. He also perceived that by favoring the Slavic element in his realm and in the Church, he would find the popular support necessary for his attempt to break the powerful class of the boyars who opposed his autocratic tendencies. He received the refugees from Moravia, therefore, with every honor and gave them every opportunity to continue their activities in Bulgaria. At a later date, Symeon appointed their leader, St. Clement, to the bishopric of Veliča, near Ochrida.

His see became an important center of the Slavonic liturgy and Slavonic literature. By this time the Bulgarians were gradually being completely Slavicized and most of the differences which had existed between the Turko-Bulgar ruling class and their Slavic subjects were now disappearing. In Bulgaria, the disciples of Methodius naturally returned to the Greek rite translated into the Slavonic language, because this was the rite in common usage in their new home and one of them even adapted the Slavonic alphabet invented by Constantine-Cyril (later called Glagolitic), bringing it closer to the Greek alphabet. This new alphabet, which later received the name Cyrillic, is still used by all Orthodox Slavs.

1. See above, pp. 100 ff.

![]()

122

It was thus in Bulgaria and not in Moravia that the first Slavonic Church was firmly established. Boris did not dare to proclaim the complete and formal independence of this Church, being quite content with at least a measure of genuine independence. The formal foundation of a special Patriarchate of Bulgaria was reserved for his son and successor, Symeon the Great, about 925. The initiative of the Bulgarian khagan was, however, of the greatest importance; for not only did his idea succeed, but it survived for centuries after having been accepted by the Serbs, the Russians and the Rumanians. It would be difficult indeed to find in all history another example of a newly converted prince so effectively influencing the evolution of Christianity.

In the meantime, Byzantine, Frankish and Roman interests were clashing in other parts of the Balkans and in Croatia. Among the tribes which were later to form the great Serbian nation, the most dangerous were the Narentanes, who were settled near the delta of the river Neretva (Narenta). From there this tribe occupied a number of important islands in the Adriatic — Meleta (Mljet), Korkura (Korčula), Issa (Vis), Pharus (Hvar), Barzo (Brać)—and developed into a kind of Slavic Vikings who threatened the safety of the sea route through the Adriatic from Venice to Byzantium. The Venetians therefore were most anxious to secure the friendship of the Narentanes, or at least to render them harmless. At last in 830 envoys of the Narentanes, exhorted by the Doge John, consented to be baptized in Venice. In spite of this favorable beginning, however, the Narentanes were again at war with Venice in 840. The Venetians were also alarmed at the growing maritime power of the Dalmatian Croats, who had equipped a small flotilla to defend their territory against the frequent raids of the Arabs, and in order to secure a maritime monopoly, the Venetians concluded a treaty in 840 with the Emperor Lothair I (840-855), son of

![]()

123

Louis I, the Pious, the conditions of which provided for the defense not only of Istria but also of the Italian coast against Arab incursions.

The Croats of Dalmatia, although nominally still under Frankish supremacy, could hardly escape the influence of the coastal cities, which were under Byzantine suzerainty. There is no information about Bornas successor, Vladislav (821-about 835), but Mislav (about 835-845) and Trpimir (845-864) were in friendly contact with the coastal cities and they granted many privileges to religious foundations there. They also transferred their residence to Klis, near Split (Spalato), in order to be nearer this center of the last Byzantine possessions on the Adriatic. The friendly relationship between Dalmatian Croatia and Byzantium was illustrated by the fact that when Zdeslav, Trpimir’s heir, was deprived of the succession by Domagoj (about 864-876), he took refuge in Constantinople, where he awaited his opportunity to return to his native land.

The Byzantines were still nursing the hope of regaining control over the whole of ancient Dalmatia and their prestige grew considerably in those parts when, in 867, the Emperor Basil I (867886) succeeded in relieving Ragusa (Dubrovnik) which had been besieged and cut off by the Arabs. The Slavic tribes of modern Serbia, with the exception of the Narentanes, recognized Byzantine overlordship and a special mission of priests headed by a high imperial official succeeded in reintroducing Christianity among them. The Serbs and the other tribes were, however, able to preserve a large measure of autonomy in the management of their own affairs.

A further Byzantine success was registered in 870. The imperial fleet attacked the coast of Dalmatian Croatia while the Croatian navy was supporting the attempt of the Emperor Louis II to capture Bari in Italy from the Arabs. As a result of this Byzantine victory even the Narentanes had to acknowledge Byzantine supremacy. Then in 874, an attempt was made to provoke a coup ďétat in Croatia against Domagoj.

Domagoj, taking advantage of the troubles which followed the

![]()

124

death of Louis II in 875, refused to accept the supremacy of Carloman, son of Louis the German, who according to a previous agreement was supposed to take over Bavaria with its Slavic vassals. Carloman s army, led most probably by Kocel of Upper Pannonia, was defeated (876) by Domagoj’s successor, his son Jljko. Kocel, the unfortunate son of Pribina, lost his life in this battle, and afterwards it seems that Upper Pannonia was ruled by Prince Brasla (Braslav).

Once Byzantine prestige in the coastal cities had been restored and the Slavic tribes in modern central and southern Serbia were under Byzantine supremacy, the time was judged to be propitious for the realization of Byzantine aspirations in Dalmatian Croatia, and in 878, Zdeslav invaded and defeated Jljko, son of the usurper Domagoj. The situation seemed extremely grave for the Croats and for the Latin Church. If the Byzantines and their ally Zdeslav could confirm and consolidate their hold over Dalmatian Croatia, Byzantine political influence, Byzantine culture and perhaps also the Greek rite would be extended, possibly forever, over the whole of the Balkans and over Dalmatia and ancient Pannonia. The Eastern Church would have extended its influence to the very gates of Italy and Germany, and there would never have been any difference between the Croats, who belonged culturally to Western Europe, and the Serbs, whose civilization was essentially Eastern.

But Western influence was already firmly established among the Croats and the situation was saved by the Croat Church. The elected Bishop of Nin, Theodosius, was jealous of the growing influence of Spalato, whose bishop was claiming jurisdiction over the whole of Dalmatia as heir of the Metropolitan of ancient Salona and realized that his power would be broken if the Byzantines were victorious. So he became leader of the anti-Byzantine opposition and worked steadily to prepare for the downfall of Zdeslav. The national Croat party rallied round Branimir, who is of unknown origin, and Zdeslav, ill-supported by Byzantium, was defeated and killed in 879. [1] Branimir (879-892)

1. Professor R. Jakobson notes that the Slavic hagiographical tradition connects the downfall of Zdeslav with the intervention of Methodius. (See the "Short Life of Methodius” published in the Fontes Rerum Bohemicarum I, p. 75.) This tradition seems to be based on some facts; unfortunately the evidence quoted is slender and confused. Methodius was in Moravia during the Croatian crisis and he went to Rome in 880, summoned by the Pope, who was alarmed by accusations launched against the Moravian Metropolitan. It seems that the Pope was informed about these accusations by the priest John of Venice, who was the Pope’s agent at the courts of the Slavic princes and who played a role in the Croatian reversal. This does not seem to warrant the above tradition. Methodius may, however, have visited Dalmatian Croatia on his return from Rome, perhaps at the request of the Pope John VIII, who was anxious to attach Croatia more closely to Rome. It is possible that the Slavonic liturgy, approved by the Pope in 880, started to spread in Dalmatia at that time and that the Pope used Methodius’s influence and the Slavonic liturgy to detach the Croats from Constantinople. In this way we can explain how it happened that Methodius’s name was mentioned in connection with Zdeslav’s downfall.

![]()

125

became ruler of the country, but after his death the old dynasty of Trpimir was reinstated on the Croatian throne. The narrow escape which the Western Church had in Croatia was of the utmost importance for Western civilization and in spite of occasional fluctuations in later years, the boundary between East and West remained forever at the gates of Croatia.

The importance of these events is enhanced by the fact that soon afterwards, or perhaps at the same time, the Slavonic liturgy in use in Moravia began slowly to penetrate through Pannonia and Pannonian Croatia, into Dalmatian Croatia. This time, it was the liturgy of the Roman rite, which was also in use in Moravia. The history of this penetration is not known, but it was slow and pacific and it can best be understood if it is recalled that Pannonian Croatia was a part of the diocese of Sirmium, which was formed for the Archbishop Methodius.* 1 What this would have meant had Byzantium won the day in Dalmatian Croatia can be gauged by what happened in Bulgaria.

The Slavonic liturgy took firm root in Dalmatia, where it survived

1. We have very little information on the spread of the Slavonic liturgy in Pannonian Croatia and only a few writers have dealt with this problem. For more details see the study by F. Fancev, “The Oldest Liturgy in Pannonian Croatia” (Zbornik Kralja Tomislava [Zagreb, 1925], pp. 509-553), written in Croat with a résumé in French.

![]()

126

for many centuries and is still in use in some places along the Dalmatian coast1 as a curious reminder of the struggles between the Franks, the Slavs, Byzantium and Rome for political and cultural supremacy in Central and Southeastern Europe in the ninth century.

There is one other fact that deserves special mention and that has not yet been noticed by historians. It is curious to note in the letters of the Popes of this period — Nicholas I, Hadrian II and John VIII — addressed to the Slavic princes of Moravia, Croatia and Bulgaria, that the writers particularly stress the fidelity of these princes to St. Peter. This is the first stage in the development of the theocratic theory later emphasized by so many Popes of the Middle Ages, especially Gregory VII and Innocent III, for as early as the second half of the ninth century, Rome was trying to bring the new realms under its special protection and to make them the instruments of its policy.

Thus it happened that Byzantium failed to realize all its political aspirations in the Balkans. It did, however, win a great cultural victory in eliminating the Franks and the Papacy from Bulgaria and in securing a firmer cultural hold over the Slavs of modern Serbia. Boris of Bulgaria eventually became a very good Christian and resigned his throne in 889 in favor of his son Vladimir to become a monk. Only once did he leave his solitary retreat and that was when Vladimir began to support a pagan reaction in his country. Boris then exchanged his monk’s garb for the accoutrement of the soldier. He called his faithful boyars together, defeated the rebels, punished his son by putting out his eyes, and returned to his monastery to continue his meditations, conscious of having completed an act of much piety.

1. The best known specialist on Slavonic liturgy and literature in Dalmatia is J. Vajs, Professor at Charles IV University in Prague. See his bibliographical data in Slovanské Studie, published in Prague in 1948 by J. Vasica.

![]()

127

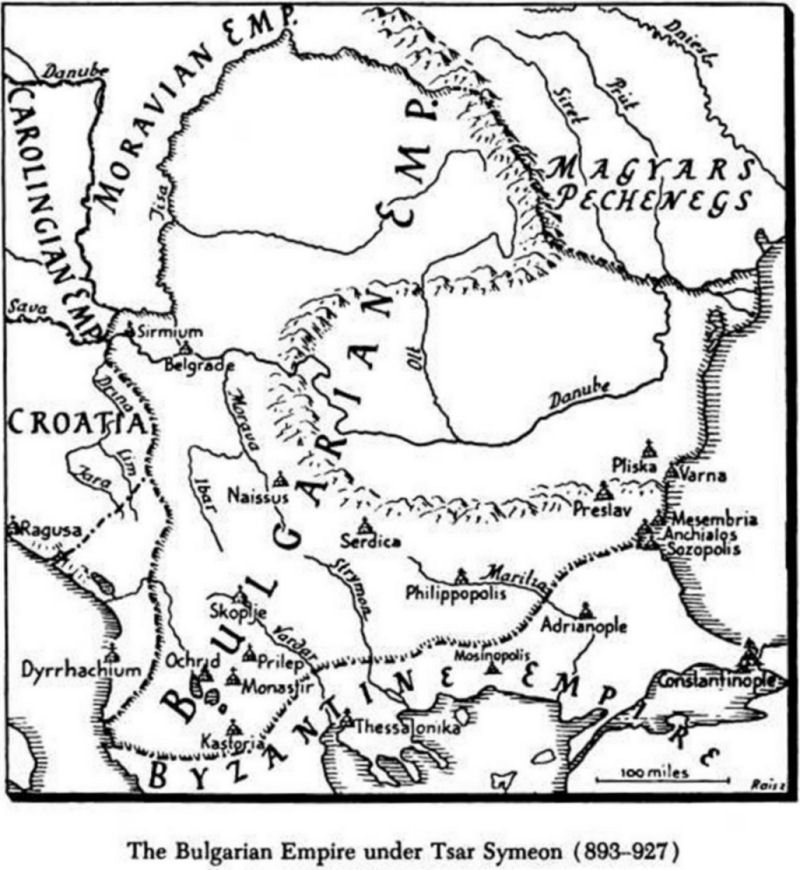

But the new khagan, Symeon (893-927), Vladimir’s younger brother, proved to be much more dangerous to the Byzantines than Boris had been. His pious father had planned an ecclesiastical career for him, and to this end had had him educated at the patriarchal academy in Byzantium. He became, indeed, a distinguished Greek theologian and it is of no small interest to study the letters which the learned Patriarch Nicholas Mysticus exchanged with him at the time when the Tsar was pounding at the gates of Constantinople.

Already in 894 the Byzantines had to experience the consequences of the change in the Bulgarian political situation. Symeon, complaining that the Byzantines had violated the commercial treaty with Bulgaria, invaded the territory of the Empire and routed the imperial army. Seeing that they were unable to bring Symeon to a halt by their own resources, the Byzantines persuaded the Magyars — who at that time were established in the steppes of southern Russia — to attack the Bulgars in the rear. This sudden onslaught, combined with the dangerous manoeuvres of the Byzantine army and navy, was formidable; but Symeon withstood it. He concluded an armistice with the Byzantines and with the help of the Turkic Pechenegs (Patzinaks), the new invaders of southern Russia, he inflicted such heavy losses on the Magyars that they retired and did not return. This reversal seems to have induced them to invade Moravia and to settle down in Hungary. They also occupied the lands between the river Tisza and the Carpathian Mountains, a territory which had belonged to Bulgaria since the time of Krum, but in which the Bulgars had never shown any particular interest.

After dealing with the Magyars, Symeon turned against the Byzantines and cut their army to pieces. In the peace treaty of 896, the Byzantines promised to pay a yearly tribute to the young Bulgarian ruler.

From that time onwards, Symeon’s power grew steadily and he extended his influence over almost all Serbian tribes and his lands prospered. His reign inaugurated the golden age of Greco-Slavic civilization when Slavonic literature flourished in Bulgaria,

![]()

128

and under Symeon s inspiration numerous important Greek works on theology and history and other sciences were translated into Slavonic. His capital Preslav was embellished by many churches and palaces, imitations of Byzantine art and architecture.

Symeon, however, did not intend to content himself with his splendid Bulgarian residence. During his studies in Byzantium the young prince had become almost a Greek. He was deeply imbued with the Byzantine political conception, according to which the Emperor of Constantinople was the only representative of God on earth and the supreme ruler of the Christian commonwealth. Symeon’s greatest ambition was to transport his capital from Preslav in Bulgaria to Constantinople itself and there to supplant the Byzantine emperors.

At first, Fate seemed to favor his plan. In 912 the Emperor Leo VI died and his brother and successor Alexander refused to fulfill the stipulations of the peace treaty of 896. Symeon, now at the height of his power, welcomed this opportunity to reopen hostilities. The debauched Alexander died in June, 913, and taking advantage of the disorders which followed at Byzantium, Symeon invaded Thrace. A military revolt had deprived the government of the means to oppose the Bulgarians and the way to the capital thus lay open. Shortly afterwards the gates of the city “guarded by God” shook to the triumphant shouts of Symeon’s soldiers.

The situation seemed desperate for the Byzantines. The new Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetus, the legitimate heir, was still a mere child and the Patriarch Nicholas Mysticus, who presided over the Regency Council, thought it necessary to enter into negotiations with the victorious Bulgarian in order to save the city and secure the throne for the young Emperor. Symeon knew well that, without a navy, it was hardly possible to take the city by assault and was, therefore, ready to negotiate. The agreement that followed arranged that the young Emperor should marry Symeon’s daughter and that Symeon should be crowned as co-emperor.

![]()

129

11. The Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Symeon (893-927)

![]()

130

The coronation ceremony was performed in the imperial palace by the Patriarch in the presence of the young Emperor and the members of the Regency Council. Contrary to what many historians say, it was not a mock ceremony, but a genuine coronation [1] and the Bulgarian monarch became thus Basileus. The question is whether the Byzantines had acknowledged, on that occasion, Symeon as the Basileus of Bulgarians only, or of the Bulgarians and of the Romaeans, as the Byzantines called themselves, thus stressing that they were Rome’s heirs.

Symeon seemed to be at the threshold of the realization of his ambitious dreams; for as co-emperor and Basileopator — the Emperor’s father-in-law — he would be able to direct the policy of the Empire. Then, loaded with rich presents, the new Basileus returned to his residence in Preslav.

Unfortunately, his luck did not last. By the intervention of an ambitious and proud lady the possibility of a peaceful amalgamation of Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire was prevented forever. Zoe, Constantine VII’s mother, who had been removed from the palace by Alexander, came back to power and took the Regency into her hands. She was horrified at the idea that her son should marry a “barbarian” princess, and repudiated the agreement made by the Patriarch with Symeon.

Symeon, greatly disappointed by this turn of events, invaded the Empire, but in 917 the Byzantines then prevailed upon the Turkic Pechenegs to attack Wallachia and as a result the Bulgarians lost all their possessions on the left bank of the Danube, which were, however, of little importance to them. Because of a lack of agreement between the imperial agent who was leading the Pecheneg hordes and the admiral Romanus Lecapenus, who had to transport them into Bulgaria proper, the worst was averted for Symeon and he was able to inflict two subsequent crushing defeats on the imperial army. The Byzantines created

1. Cf. G. Ostrogorsky’s and F. Dölger’s studies dealing with this problem published in the Bulletin de l’institut Archéol. Bulgare IX, 1935 (“Die Krönung Symeons von Bulgarien," pp. 276-286; “Bulgarisches Cartum und Byzant. Kaisertum," pp. 57-68).

![]()

131

a diversion by urging the Serbs to rise against Symeon but, in the end, their attempts proved vain. If Symeon had appeared before Constantinople in 918, when the power of the Empress was crumbling because of the disastrous military defeats and when the city was on the brink of anarchy, he might have achieved his aim with the help of the Empress’s enemies. However, for unknown reasons, Symeon missed this opportunity and the Regency was taken over by a new upstart, the Armenian peasant Romanus Lecapenus.

Refusing to accept the new situation, Symeon continued his bloody invasions hoping to enforce the deposition of the new rival who, in the meantime, married his daughter to the young Emperor and became the reigning Emperor. The exhortations addressed to Symeon by the Patriarch and by the Emperor himself were all in vain and the Bulgarian continued to use the title “Basileus and autocrator of Bulgarians and Romaeans.” In this mood he established the independence of the Bulgarian Church about 925 by the foundation of a special Bulgarian Patriarchate. Symeon s negotiations with the Fatimid Calif of Africa to secure the help of the Arab fleet against Constantinople were luckily checkmated by Byzantine diplomacy and money. But not even after his interview with the Emperor and the Patriarch under the walls of Constantinople in 924 was Symeon reconciled to the evil change in his fortunes.

It has been suggested by F. Šišić and V. N. Zlatarski, the leading Croatian and Bulgarian historians, that Symeon finally turned to Pope John X with the request for recognition of his imperial title, asking the Pope to send him a crown and scepter and to confirm the establishment of an independent Bulgarian Patriarchate. There is no evidence for such a démarche from Symeon’s side. It is true that John X had sent his legates — whose main function was to investigate the religious situation in Croatia and to preside at the Synod of Spalato — to Bulgaria in order to promote peace between the Tsar Symeon and the Croat King Tomislav. Symeon, anxious to secure his western frontier before launching his final attack against the Byzantine Emperor, had

![]()

132

sent an army against the Croats, then the Emperor’s allies. His army, however, suffered a major defeat and Symeon was preparing a new campaign. The Pope feared that the new war would compromise Rome’s interests in Croatia, then being ecclesiastically reorganized under the primate of Spalato. He himself took the initiative and sent his legates to Symeon. According to the Acts of the Synod of Spalato, their intervention met with success and peace was concluded between Symeon and Tomislav.

There is, however, no contemporary evidence that Symeon on this occasion addressed a request to the Pope for recognition of his imperial dignity, or for a crown and a scepter. Symeon, who was so deeply imbued with Byzantine political ideas, could hardly have thought of addressing such a request to the Pope. The only argument brought forward in favor of such a supposition — the letter of Kaloyan (from the year 1204), the founder of the second Bulgarian Empire, to Pope Innocent III [1] — is not conclusive. In the thirteenth century, when the papal theory of the supremacy of the spiritual power over the temporal was universally recognized, the situation was quite different, but ideas which were current in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries must not be transferred to the tenth century. Symeon would have gained nothing from the recognition of his dignity by the Pope and he never took any steps to seek it.

Fate denied Symeon the realization of his ambitious dreams. Before he was able to organize a new campaign for the conquest of Constantinople, he died in 927 and when the news reached Constantinople the whole Empire gave a long sigh of relief. The Byzantines could now happily forget the humiliating scene

1. Kaloyan claims in his letter that, after carefully examining the writings dealing with the reigns of his predecessors Symeon, Peter and Samuel, he found that they had all received their crowns from the Roman See. This is in contradiction to his previous letter in which he says simply that Peter and Samuel had the imperial title, without mentioning Symeon or Rome. The astute prince exaggerates in order to curry favor with the Pope. There is certainly no evidence that the Tsars Peter and Samuel received the crown from the Pope. Why should his statement concerning Symeon be accepted literally?

![]()

133

which had taken place in the imperial palace in 913 and, in order to cover up the fact and to save the honor of the Empire, the rumor was circulated that Symeon’s coronation was not a valid one, because the Patriarch had deceived Symeon by placing on his head, instead of the imperial diadem, only the cover of his head-dress. Symeon the Logothetes, followed by Skylitzes, recorded this rumor in his Annals and led many historians into error.

It was inevitable that the swift rise of Bulgaria under Symeon should influence the development of Croatia and Serbia, and the Croats benefited considerably by the decline of East Frankish (German) power at the end of the ninth century. At the same time the Dalmatian Croats became independent and it was thought that the propitious moment had arrived for the Croats to create a political union of Dalmatian and Pannonian tribes. This was achieved by the Duke of the Dalmatian Croats, Tomislav (910-928), the successor of Mutimir (892-c.910), and during his reign Pannonian and Dalmatian Croatia were welded into one. The motive of the Pannonian Croats in desiring the union was most probably dictated by the Magyar danger. Tomislav assumed the title of King of the Croats and, in 925, he was recognized as such by the Pope John X. It was an important turning point in Croat history.

In Serbia proper — a territory generally called Raška in the Middle Ages — there reigned the dynasty of župans, founded by Višeslav about the year 780, and after the death of his third successor, Vlastimir (about 835-860), the country was governed by Vlastimir’s three sons, Mutimir, Strojimir and Gojnik. Mutimir was the prince who had been exhorted by Pope John VIII to join the metropolis of Sirmium, founded for St. Methodius. He governed alone after driving his brothers from the country, a usurpation of power which was responsible for long dynastic struggles after his death (about 890) between his brothers’ sons and grandsons. These struggles were cleverly exploited for

![]()

134

their own ends by Serbia’s neighbors, especially Bulgaria and Byzantium. The most energetic of these later princes was Peter, son of Gojnik (891-917), who extended Serbian domination over the Narentanes. But when Peter agreed to a Byzantine proposal that he should attack Symeon of Bulgaria, the latter, warned of the plan by Michael, Prince of Hum (Zachlumje, modern Herzegovina), swiftly placed another pretender on the Serbian throne. Further Serbian intrigues with the Byzantines resulted in the complete occupation of Serbia proper by Symeon of Bulgaria. Only the Prince of Hum preserved his independence, first as an ally of Bulgaria and then as a supporter of Byzantium.

During the Bulgaro-Byzantine wars there was a dangerous possibility that the Bulgarians would advance as far as the Adriatic and conquer the Dalmatian cities which were still in Byzantine hands. Unable to check this menace alone, the Emperor Romanus I (919-944) ceded all the towns and islands of Dalmatia to the Croat King Tomislav in order to secure his neutrality in the struggle with the terrible Bulgarian. Tomislav was given the title of proconsul and was supposed to rule over the “theme of Dalmatia” as the Emperor’s representative.

This new situation found its expression and confirmation in the first important provincial Council of the Croat Lands, held in 925 at Spalato. Some of the Serbian princes, driven from their own territory by the Bulgarians, were present at the meeting, together with all the Dalmatian bishops and abbots headed by the Bishop of Nona (Nin) and King Tomislav himself. This was the first Serbo-Croatian demonstration ever to be held in Dalmatia. At this meeting the Archbishop of Spalato was proclaimed Metropolitan of the whole Adriatic seaboard from Istria to Cattaro and three years later another Council held at Spalato confirmed this decision by suppressing the first Croat bishopric of Nona.

Bulgarian pressure on Serbian territory and its princes diminished after the death of Symeon in 927. In 931, the prince of Serbia proper, Česlav, revolted and, with the help of the Byzantines, the Croats and the Prince of Hum, regained his independence

![]()

135

under nominal Byzantine sovereignty. Taking advantage of troubles in Croatia after the death of Tomislav, he was even able to extend his possessions by occupying Bosnia, which, until then, appears to have formed part of Croatia. [1] The Narentanes on the Dalmatian coast began their sea-borne raids once again. Venice had to take up arms against them and eventually defeated them in 948.

The complications which followed the death of Tomislav resulted in the loss of direct political control of the theme of Dalmatia by his successors, the legendary Trpimir II (about 928-935), Krešimir I (about 935-945), Miroslav (945-949), and the imperial proconsul of Zadar (Zara) took over the administration.

The prestige of Croatia began to rise again under King Krešimir II (949-969), who regained Bosnia and restored good relations with the coastal cities, and his son Stephen Držislav (969-997), who succeeded him, brought the realm to a new high level of strength and power. Byzantium could not remain blind to this fact and did not hesitate to acknowledge it. In 986 the Emperor Basil II sent the royal insignia to Držislav and restored him to the governorship of the Dalmatian theme. The Croat King then became eparchos and received the high-ranking title of Patricius and for the first time the King officially described himself as “Rex Croatiae et Dalmatiae.”

But Dalmatia had long been coveted by another power rising on the Adriatic — Venice. Under the leadership of the doges of the Orseolo family, Venice grew more and more conscious of her power and in 996 Peter II Orseolo (991-1009) refused to pay the annual tribute due to the King of Croatia. Taking advantage of the fact that Držislav’s sons and successors, Svetoslav (997-1000), Krešimir and Gojslav, who should have shared the throne,

1. The territory called Bosnia at that time comprised only the upper valley of the river Bosna to the middle Drina. I am dealing with the problems of Croatian and Serbian history to the eleventh century more thoroughly in the commentary to chs. 27-36 of Constantine Porphyrogennetus’ De Admin. Imperio in the forthcoming second volume of the edition by Gy. Moravcsik and R. J. H. Jenkins.

![]()

136

12. Croatia ca. 1050

![]()

137

had started to quarrel among themselves, Venice concluded an agreement with Byzantium by which the Emperor ceded to her his nominal sovereignty over the Dalmatian towns and islands, and in the year 1000 the Doge Peter II occupied the whole Adriatic seaboard, taking the title of “Dux Dalmatiae.”

Years of rivalry between Croatia and Venice were the result, both parties striving to hold or to reconquer the Adriatic coast. King Krešimir III (1000-c. 1030), who made his brother Gojslav (1000-1020) co-regent, having concluded a peace treaty with Venice, renounced the tribute which the Republic had refused to pay and agreed that the Doge should assume the title of “Dux Dalmatiae.” His son received Orseolo’s daughter in marriage (1008). But in spite of these concessions the struggle for Dalmatia went on.

In 1018 even Croatia acknowledged the supremacy of Byzantium when Basil II, after destroying the Bulgarian Empire, stood on the frontiers of Croatia. As Patricius of the Byzantine Empire — the title was given to him by the Emperor — Krešimir III thought perhaps that he was entitled to occupy the theme of Dalmatia when the Orseolos were driven from power in Venice, but he was mistaken. The Byzantines intervened and from 1024 onwards the coastal cities again came under the direct supremacy of Byzantium and were governed by the imperial proconsul of Zadar (Zara). Further attempts made by Krešimir III and his successor Stephen I (about 1030-1058) to regain control over these cities, with the help of the Hungarian king St. Stephen, were not successful.

Only Peter Krešimir IV (1058-1073) met with any success. He extended Croatian sovereignty once more over the whole Byzantine theme of Dalmatia. This happened probably about 1069, when the Emperor Romanus IV (1068-1071), hard pressed by the Seljuk Turks in Asia and fearing that the Normans from Sicily might get a foothold on the Adriatic, consented to the incorporation of the small Dalmatian theme into the Croatian kingdom. Krešimir IV extended his power as far as the Narenta. He ruled in the coastal cities not as proconsul or imperial

![]()

138

representative — as Kings Tomislav and Držislav had done — but as sovereign, and in his royal charters he proudly called the Adriatic “nostrum Dalmaticum mare.” Croatian power was at its height.

Byzantium was not especially concerned in interfering with the growth of Croatian power. The country was too far from the Empire’s immediate interests to warrant any particular anxiety. But Bulgaria was close at hand and her power was still redoubtable. Here, the Byzantines were favored by fortune. Symeon’s son and successor, Peter (927-969), was a pious man, but lacking his father’s energy and ambition. He was granted the title of “Basileus of the Bulgarians” and married the Emperor’s granddaughter. He made peace with Byzantium and Greek influence began to grow strong once more in Bulgaria. This unpopular move provoked a new insurrection of the national party in Bulgaria.

Popular discontent with the growing Greek influence at the Bulgarian court found a curious expression in the rise of a new heretical sect, the Bogomils, whose teaching was a development of the dualistic doctrine of the Manichaeans of Persian origin and their heirs, the Paulicians. The latter were very numerous in the border districts between the Arab and the Byzantine Empires in Asia Minor. In the eighth century thousands of Paulician families had been transferred by the Byzantine emperors from Asia Minor into the Balkans. This was done in order to break their power, which was dangerous not only to Orthodox doctrine but also to the State on account of their alliance with the Arabs. While the Paulicians mixed naturally with the Slavic peoples in their new habitat, a considerable number remained faithful to their old creed. The Bogomil sect rose to power in the tenth century owing to the activities of a sectarian leader called Bogomil.

The Bogomils believed that the visible world was created by Satanael, the first son of God, who had been rejected — with his

![]()

139

angels — by his father because he revolted against him. Satanael created also the body of man; but the soul was a product of God the Father. In order to save the human race, God the Father sent his second son — the Word — into the world. He entered into the body of the Virgin Mary through the ear, was born, and taught men how to defeat the world and its creator. Through his apparent suffering and death —he could not suffer in reality, being God’s son — he liberated man, deprived Satanael of his divine nature — henceforth the latter is called only Satan — and took his place at the right side of God-Father.

The sectarians rejected the Mass, the Sacraments, all images and the Cross, because they were connected with materia which was the work of Satan. They also opposed marriage and taught civil disobedience. They accepted only the New Testament and the Psalms, claiming that the Old Testament was the work of Satan. Details of their origin and their beliefs are not thoroughly known. There is still some mystery about the way the sect spread through the Balkans and about its influence on the origins of the Albigensians or Catharists of Albi, who became so well known in northern Italy and southern France in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The Bogomils played an important role in Balkan history. On occasions they succeeded in gathering round them the national and popular opposition to the Greeks, the official Church and the nobility. All this greatly weakened the Bulgarian State, which also suffered considerably at that time from the incursions of the Magyars and Pechenegs.

The Byzantines followed this development with the keenest interest. It has already been shown how in 931 they had secretly supported the revolt of the Serbian prince Česlav (d. 960), and the Emperor Nicephorus Phocas (963-969), infuriated with the Tsars request for the payment of tribute — or, rather, of the dowry of the Tsaritsa Mary-Irene, a Byzantine princess, which was to have been paid in instalments from 927 but ceased after her death in 965 — decided to break the Bulgarian State, which was still regarded as dangerous. He was able to persuade the

![]()

140

adventurous Russian prince Svjatoslav (962-972) [1] to invade Bulgaria. This took place in 967 when the Russians from Kiev crossed the frontier near the Danube delta and occupied the eastern part of Bulgaria. Svjatoslav intended to keep this territory forever and even to transfer his capital to Perejaslavec (Little Preslav). But the sudden and violent attack launched by the Pechenegs on Kiev forced him to abandon this plan and depart from the lands he had conquered (968).

He returned, however, in the next year when he had routed the Pechenegs and destroyed the Khazar empire. Then the new Bulgarian Tsar, Boris II (969-972), had to go through a very difficult period; for the whole of the western part of his realm refused him obedience, the remainder was overrun by the Russians, and he was taken prisoner by the invading army. Svjatoslav, emboldened by success and greedy for yet more spoils and tribute, rejected the peace offer of the Byzantine Emperor John Tzimisces (969-976) and attacked the army of Byzantium, but he was defeated and in 971 the Emperor expelled the Russians from eastern Bulgaria. After a desperate and futile attempt to escape with his army from Dristra (Dorostol, Silistria), the last fortress besieged by the Byzantines, Svjatoslav had to acknowledge final defeat. He had to evacuate eastern Bulgaria, which became a Byzantine province, and to content himself with a commercial treaty with the Empire. On his way back to Kiev he was cruelly murdered by his old enemies the Pechenegs.

The Byzantines won the cooperation of the Bulgarians against their common enemy only because they posed as the liberators of Bulgaria, but in point of fact, after the defeat of the Russians, the whole eastern part of the country was occupied by Byzantine forces and Boris II was taken to Constantinople where he was obliged to provide a spectacle for the triumphal procession of the Emperor. Even the Bulgarian Patriarchate, the seat of which had been probably transferred according to the stipulations of the treaty of 927 to Dristra (Dorostol) was completely destroyed.

1. On Svjatoslav, see below, pp. 202-204.

![]()

141

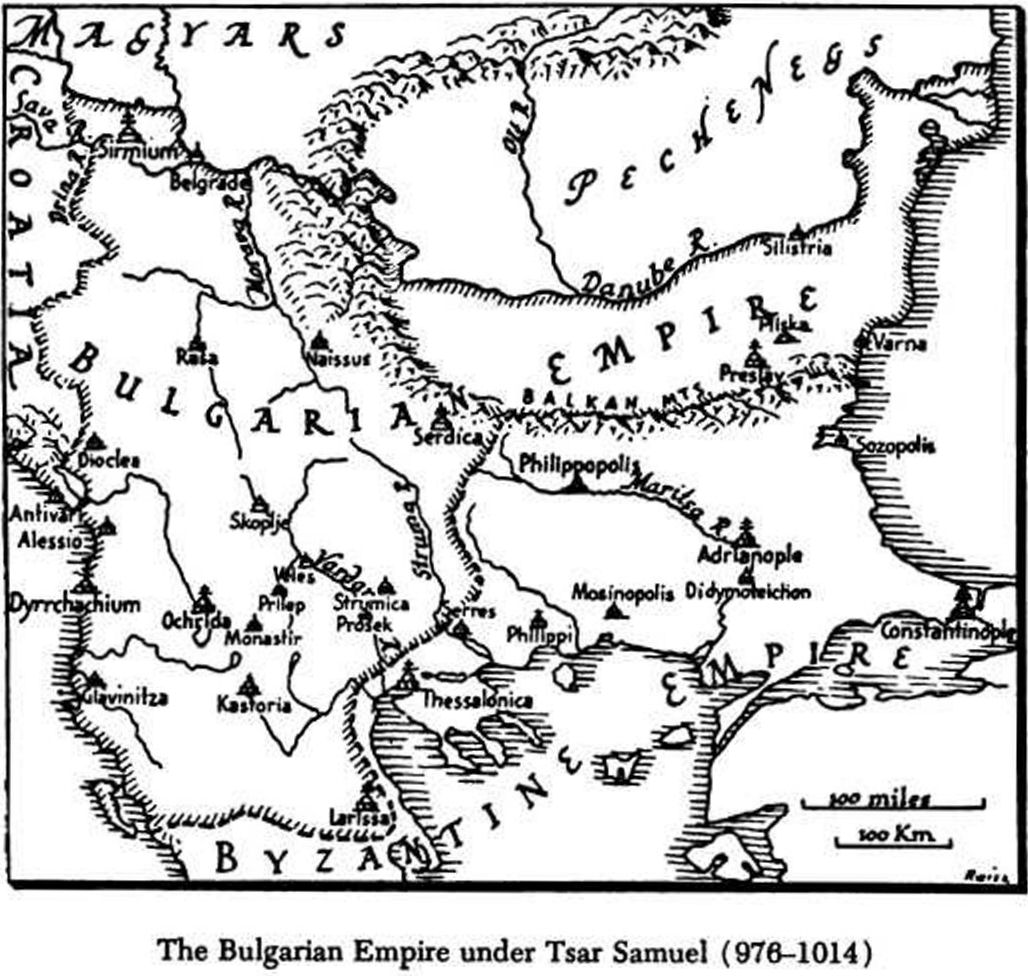

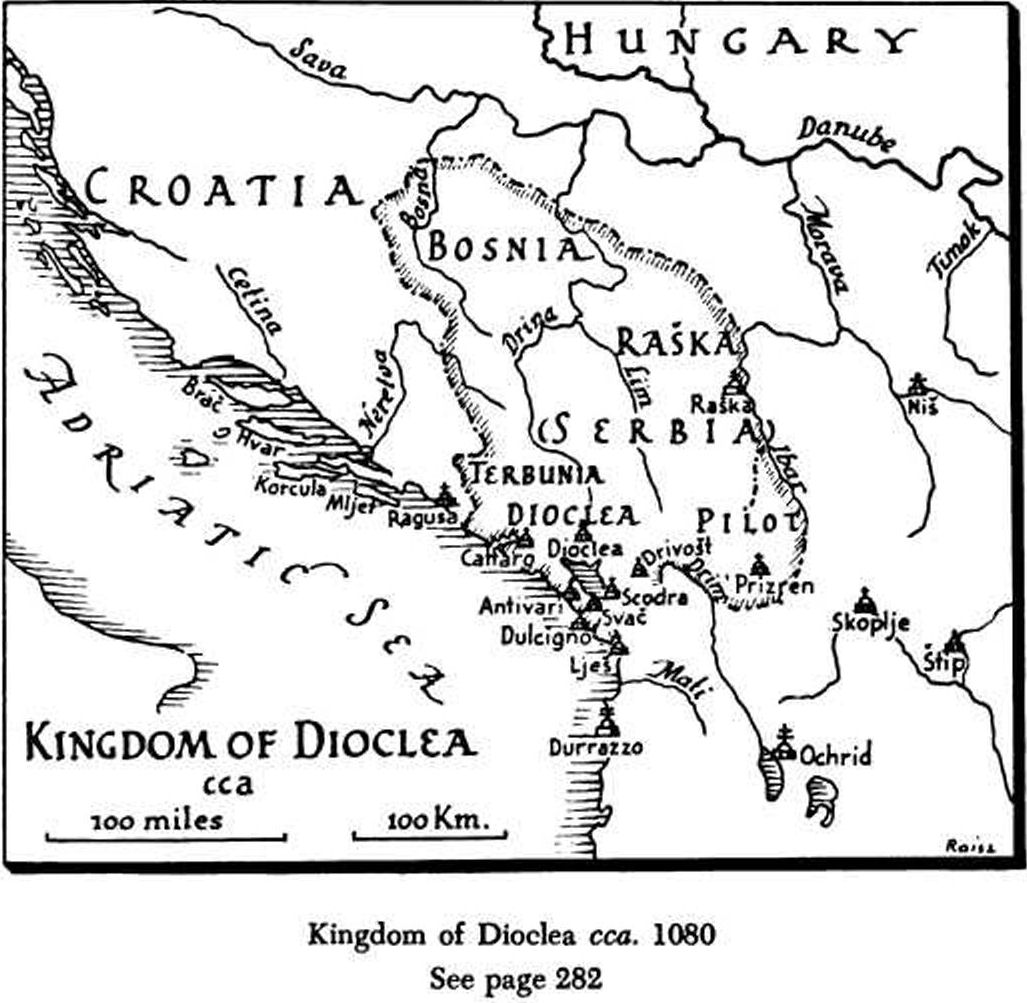

Only the western part of the Bulgarian Empire, comprising Macedonia, southern Albania and western Moesia, continued to exist as an independent country. Its first ruler was Nicholas, formerly a provincial governor, who drifted away from the rest of Bulgaria, probably after the death of Peter. He was followed by his sons, David, Moses, Aaron and Samuel. After the death of his brothers — Aaron died in 987 — Samuel ruled alone as tsar from c. 996 to 1014. The Bulgarian capital was transferred from Prespa to Ochrida and this city represented the national aspirations of all Bulgarians. A Patriarch, Gabriel or Germanos, was established, first at Sofia and Prespa, while his successor, Philip, resided at Ochrida. The Tsar Boris II and his brother Romanus looked to this territory as the sole hope of their nation, and when they succeeded in escaping from Constantinople, they fled to join Samuel. Boris lost his life at a spot near the frontier, and his brother, having arrived safely, was obliged to surrender all his rights to his host.

The aspirations of Samuel were certainly significant. It was his intention to unite all the Balkan Slavs under the leadership of Bulgaria and to use this combined force to crush Byzantium, the only power which could stand in the way of the realization of his dream. The situation seemed to favor his plans; for Byzantium was having to fight the Saracens in Asia and in Sicily, while in Italy she was faced with the pretensions of the German Emperor Otto II. Samuel’s initial successes can, indeed, be explained by these Byzantine difficulties; for his first invasion of Byzantium swept all opposition before it. He pushed as far as the Peloponnese and defeated Basil II (976-1025), when the Byzantine Emperor attempted (in 986) a drive towards Sofia. Then Samuel started upon his campaign for the reunion of the Southern Slavs.

He invaded Serbia proper, defeated Vladimir, Prince of Dioclea, [1] overran Bosnia and the region of Srem, and reached

1. Prince Vladimir of Dioclea seems to have been an ally of the Emperor Basil II. A Serbian embassy to the Emperor is mentioned in an Act of Mount Athos (G. Ostrogorsky, “Une ambassade serbe auprès de l’empéreur Basile II," Byzantion XIX [19491, pp. 187-194). It may be that Basil II had entrusted the prince with the administration of Durazzo, as suggested by Ostrogorsky. The embassy should be dated between 990 and 992. The envoys went by sea and were surprised on a small island near Lemnos by Arab pirates, were captured and freed through the intervention of the Emperor. The occupation of Dioclea should thus be dated not in 986, but about 993. Vladimir was reinstated in Dioclea by Samuel as his vassal.

![]()

142

13. The Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Samuel (976-1014)

![]()

143

the Adriatic coast south of Cetinje. He occupied present-day Herzegovina and put an end to the temporary independence of Dioclea and Trebinje. Even the fierce Narentanes had to bow to the Bulgarian yoke. All these victories were great achievements, and there were times when the realization of the old dream of reuniting all the Balkan Slavic peoples under one leader seemed very near.

But all was in vain. The Byzantines were slowly but surely gathering their strength. Samuel’s ambitions could not be extended to Croatian territory; for his attention was once more absorbed by events on the Byzantine frontier.

The great Emperor and general Basil II succeeded in bringing hostilities in Asia Minor to a conclusion and after the year 990 he was ready to deal with any threat from Bulgaria. A long and bitter struggle commenced, brutal and bloody and conducted mercilessly on both sides, each in turn exhibiting Oriental and Balkan fury and cruelty. The different epic phases of the struggle have been depicted in a masterly fashion by the French scholar G. Schlumberger, who did so much to revive Byzantine studies. There were scenes in this terrific conflict which surpassed anything which the genius of a Shakespeare could have imagined in the way of ghastliness and ferocious cruelty. There are few more horrible deeds in history than the blinding of 15,000 Bulgarian prisoners by the merciless victor, who spared one eye of one man in every hundred so that he might lead his helpless comrades back to the court of the unhappy Tsar. This happened in 1014, after the terrible and overwhelming defeat of the Bulgarians near Thessalonika. Well did Basil II merit his notorious

![]()

144

14. The Kingdom of Dioclea ca. 1080. See page 282

![]()

145

title — Bulgaroctonos, Killer of the Bulgarians. At the sight of his blinded army, the Bulgarian leader fell dead (October 6, 1014).

The struggle continued under his successors Gabriel-Radomir and John-Vladislav. Yet hate, treachery and murder within the Bulgarian royal family all served to help the Greeks. In 1018 the campaign was definitely concluded. The Bulgarian Empire was annexed, together with all the lands once conquered by Samuel, and, as has already been pointed out, Byzantine supremacy was extended, at least nominally, over Croatia. In the following year the aged Emperor entered the Golden Gate of Constantinople in triumph, surrounded by vast loads of spoils and captive Bulgarians, sons of a state once so powerful, now brought so low.

Thus Bulgaria became a Byzantine province and was divided into several themes, or administrative units. At the same time, the independent ecclesiastical organization of the country was terminated. The Patriarchate of Ochrida vanished; but in the early days of their rule over Bulgaria, the Byzantines wisely refrained from depriving the Bulgarians of their language and national institutions. Basil II suppressed the Patriarchate; but Ochrida remained an independent archbishopric under the Patriarch of Constantinople and was granted important privileges. [1] Its jurisdiction extended over all bishoprics existing on the territory of the former western and eastern Bulgaria, but the appointment of the archbishop was reserved to the Emperor. Basil II’s successors manifested, however, less statesmanship than the great Basileus. All Bulgarian and even the Serbian bishoprics were handed over to Greek priests. Nevertheless, in spite of some attempts to suppress it, the Slavonic liturgy survived this national disaster.

As the grip of the Byzantines over Bulgaria grew tighter from 1037 onwards, a number of insurrections broke out. The most

1. Cf. J. Granić, "Kirchenrechtliche Glossen zu den vom Kaiser Basileus II dem autokephalen Erzbistum von Ochrida verliehenen Priviligien,” Byzantion XII (1937), pp. 395-415.

![]()

146

dangerous occurred in the years 1040 and 1072. Many events conspired to prevent the Byzantines from reaping the full benefit of their occupation or enjoying the fruits of their conquest in peace and also hampered the natural evolution of Bulgarian national life. These were the invasions of the Pechenegs, the Hungarians and especially the Turkic Cumans (1064); the invasion of the Normans under Robert Guiscart (1081-1085); another Norman invasion under Boemund of Tarento in 1107; and troubles caused by the increased influence of the Bogomils. Not until the end of the twelfth century did Bulgaria emerge again as an independent country.