148

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER X.

Behold, they clap the blave on the back, and behold, he arisclh a man

SALONICA lies on a hillside. A jumble of roofs, mosque domes and white minarets, and at the top green gardens and the old embattled walls. Behind and around, more dusty hills. From the sea the first thing to catch the eye is the Bias Kula (White Tower) at the east end of the sea front, shaped like the old Pictish castles and reflected, with the long line of whitewashed houses, in the calm of the bay. Between the walls and the water dwell men and women of all peoples and tongues. Bulgarians, Servians, Albanians, Vlachs, Armenians, Anatolians, Circassians, Greeks, Turks, Jews, infidels and heretics of every land and language. Between and among these are sprinkled the races of civilised Europe, and in one exalted avenue, locally known as Consulate Row, live the representatives of their Governments.

The Greeks - always the money-makers - own the hotels and the Europe shops. The Jews control the antiquities industry and the maritime traffic. The Turks sit in high places and obstruct trade as long as passive resistance does not interfere with a

![]()

148

life of gentlemanly ease. The rest of the collection are allowed to live and ought to be grateful for it. Each "quarter" is in its appropriate place - Jews near the waterside, where they can get to their boats; Turks on the top of the hill, where they may gaze philosophically on the world and are not overlooked; Greeks in the pockets of the population. In odd corners which nobody else wants are dumped the Bulgarians and such like. Along the sea front are the hotels and a centre of delirious gaiety known as the Alhambra, where the frivolously-inclined sit among little tables on iron chairs on the gravel and watch a dingy travelling company extinguishing "La Vie de Bohéme."

Perilously near the sacred abodes of the consuls is another open-air stage, where a plump and popular French lady was wont to present a song and dance, in which she gave an entrancing imitation of the barking of a dog. One night there was a difference of opinion between the Jews and Turks present as to whether the canine cadenza should be delivered or not, which ended with the entrance of the police, the flying exit of the Jews and the closing of the local "Empire" for the rest of the season.

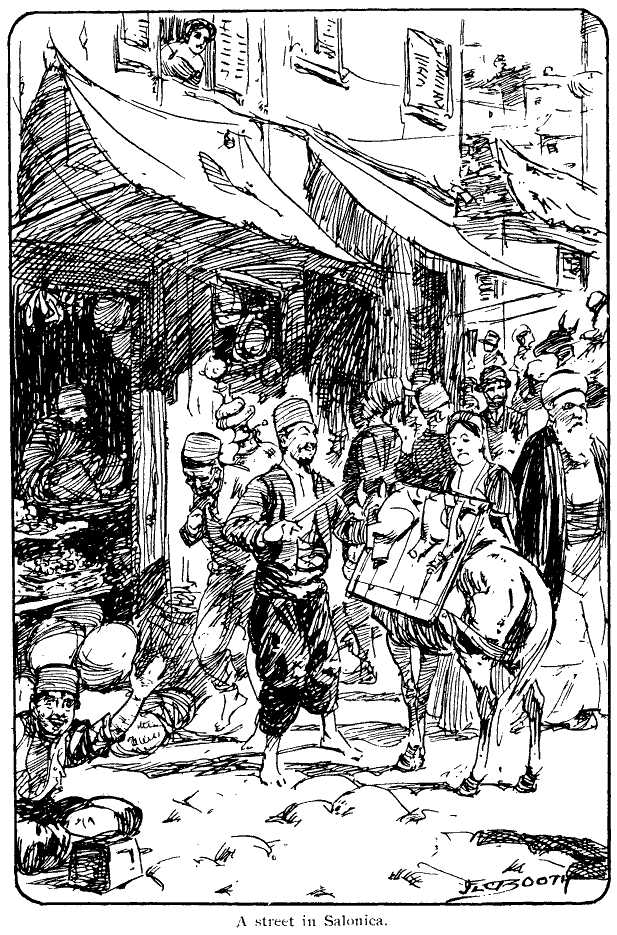

The top of the best street is roofed in to make a bazar, and in its shadow the crowded open-fronted shops spread their contents on the cobbles. Fruit piled in heaps, trousers and walking-sticks, bakers' counters with meat pasties, pointed shoes and lemonade, gaudy rugs, copper pans and comic-opera hats. Fez and turban pass the European "straw" in the crowd, and amongst them steers the bice-green head-dress

![]()

149

A street in Salonica.

![]()

150

of a sallow-faced Jewess, hanging down her back in a kind of a long narrow bag. On Saturdays - the Jewish Sabbath - the Israelite colony of course does no work. It parades in families, facing ninety-five in the shade in long fur-lined coats and girt about with many ornaments. The Levantine Jew has not what we call "Jewish features." A distinctive type he certainly is, but difficult of classification. There is something of the Slav in his square, short-nosed face, but only in isolated cases does he suggest the Spaniard whose language he talks, and whose music he uses.

Sitting on the hotel balcony one night, I was surprised to hear, coming up from the water, the quaint air of a Spanish dance played on a concertina by one of the Jew boatmen. Every night his crew pulled up and down-a shadow-mass on the quiet water - till I knew the air by heart, but I never felt the barrel-organ boredom that the naked word "concertina" might suggest.

Much of the marketing of Salonica is done on the move. The butcher, clutching a pair of scales, hauls a veteran pony roofed like a dog kennel, on which roof hang the component parts of a lamb. With their bread-crumb coating of dust and delicate flavouring of flies the tasty joints are eagerly sought after. The local milkman, with shouts of "Haidé," ["Go on."] propels a staggering ass, burdened with bulging goat-skins from which he taps into a small tin measure. The hideous war-cry of his London brother is to him unnecessary, for the far sweeter

![]()

151

voice of the milk-moke tells all mankind who comes.

Abdul.

About a year before, the Bulgarians had shown their contempt for a quiet life by blowing the Ottoman Bank sky-high, and holding a sort of bataille de fleurs with bombs for bouquets. Salonica, like the lady who has had mumps and feels sure it is coming on again, was just then going through qualms of anxiety, and her poor nerves were in

![]()

152

such a state that any shock would have sent her into hysterics. At each street corner, on an infirm rush stool, sat a soldier of the Empire in a state of mental lethargy, his trusty weapon on his bended knee. It was his cherished privilege to explode this arm against the person of any Bulgarian who showed a disposition to blow up banks or otherwise irritate our lady of Salonica. That he was not called upon to take this step was no fault of his own, and he was grievously disappointed, a day's Bulgar-shooting being one of his favourite sports. As I grew to know Abdul better I discovered in him many qualities of which at first blush one would not have suspected him. Decidedly appearances are against him, and without his rifle he has an unclassified look which might lead the hasty observer to put him down as a tramp. His covering (uniform is the last word with which to describe it) is usually of a dull roan relieved with grey patches, and varies in colour effect from a moor in the twilight to a thunderstorm at sea.

Once a year a brand new blue costume is supposed to be served out, which lasts about four months, after which Abdul has to patch up the holes with what he can find and hold up the patches with string. As soldiering in the Turkish army is largely a sedentary pursuit the most frequently-renewed repairs are on the rear of the trousers, which are usually shrunk to a painful tightness. Should his jacket be of recent issue many of the original buttons remain, but in the more fashionable back numbers these are replaced by bits of stick

![]()

153

or dispensed with altogether. The question of footwear is left to the individual taste, which works over a large range. The white socks and skin sandals of the peasant will adorn the twinkling feet of number one, setting off the bare ankles and split shoes of number two, while number three's artistic fancy leans to a torn trouser and slipper on one leg and a high boot with a large shoe over it on the other.

In feature and expression Abdul differs from our standards of manly

beauty, and could safely be turned loose in Hyde Park without inflaming

the hearts of the nursemaids, though he might be the cause of convulsions

among their charges. In the Anatolian regiments especially, a man with

an unbroken nose is looked upon by his comrades as vulgarly conspicuous,

whilst much of the winning playfulness of their smile depends upon having

two or more good gaps in their front teeth. But as he does not mind much

whether he is paid, cares very little when he is fed, and not at all how

he is clad, Abdul is the ideal soldier for the Turk's administration, whose

economy in these matters is one of the most noticeable features of his

system.

With great trumpetings the carnival figure of "Reform" had once more made its appearance in Macedonia. Hard-pressed by the Powers, the Sultan dressed up the image in the cloak of Concession, clad his feet in the boots of Financial Grants, and pulled the hat of Promises over his eyes till he looked very like the Real Thing. Then

![]()

154

he set an Inspector-General to hold him up, and pushed him into the ring. The Powers, for their part, thought he was as good an imitation as they could expect, and sent twenty-five trusty men and more to make him alive.

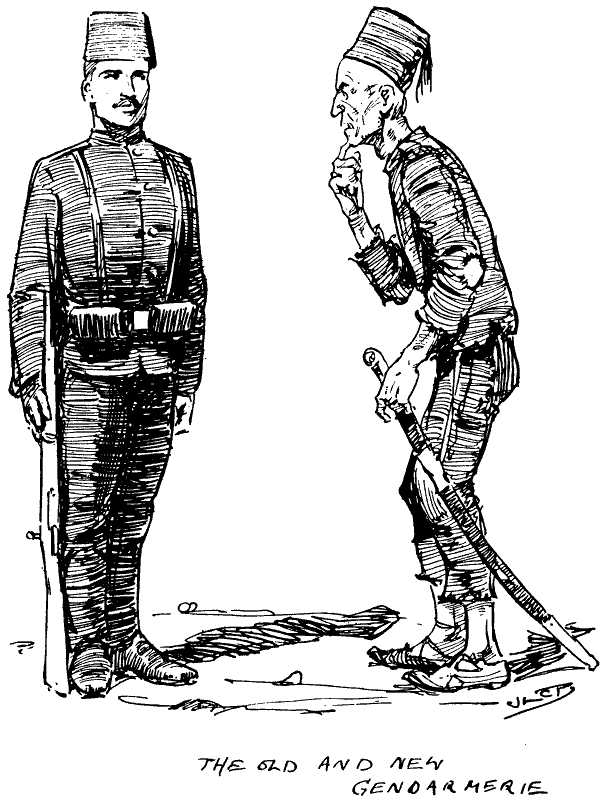

The first thing these men did was to try and fashion him some real internal organs that would work (eventually) by themselves; which, if you think of it, was a big job, because anything the figure had in that line were mere shreds that had never been alive. The one they started on was called the Gendarmerie Impèriale Ottomane.

The head doctor, called de Giorgis, was a man skilled in the making of that particular organ, and those who strove with him were accounted clever surgeons, and worked for the most part with their heads and hands, and some of them had faith. The inward knowledge of the making was not given to all, and in some the will was lacking, but by the sweat of those who gave head and hand and heart to the task, in due time this particular organ had life. Driven by its makers, the Gendarmerie Impèriale Ottomane worked inside the great image of Reform, which began to look yet a little more like the Real Thing.

But the other internal organs of the figure which lay around the new-born member were untouched, and their stagnation crippled its action. The nearest and most important was called Financial Control, and this was as the other had been, a shred without life. So the head doctor called on the Powers and said "Send others to make this

![]()

155

dead thing alive that it may work as ours works, and not overlie and smother what we have created."

The Powers are sending.

So the image, for want of its other organs, is not yet living and working,

and some call it a failure. Whereas the wonder is that it has not been

buried long ago.

The building up of the Gendarmerie was worth watching. Round Macedonia were dotted the European officers - the Russians at Salonica, the Austrians at Uskub, the French at Seres, the Italians at Monastir, and the British at Drama - five officers to each. From these centres they spread to the outlying posts of their districts, and gradually gathered in, weeded out, clothed, taught, armed and drilled the scarecrows who were to be made into a force.

A good deal of this was done at the school at Salonica, where the practical work was in charge of Major Bonham of the Grenadier Guards. In that collection of nationalities and petty jealousies he rode with so clever a hand that they buckled to and worked with each other for him. He had 'the way' with him.

Officers and men, the Turks went through the course and were shaped. They came in ignorant; without pride, discipline or interest. The life of a gendarme ("duties" is too big a word) up to then consisted in having as comfortable a time as possible in the hill village to which he was posted, and making what he could out of the inhabitants;

![]()

156

wherein he only imitated his superiors, and could therefore hardly be blamed. He helped himself by virtue of his decrepit Martini, whose ten-pound pull was never interfered with by any range practice. Officers knew nothing of their commands, rarely or never visited their posts, and lived a life of ease undisturbed by the worries of business. What they or their men did mattered to nobody. Imagine the rude shock to their systems when they found they were to be "organized " - a process distasteful to any self-respecting Turk - and still worse, by Europeans. Christians - Giaours - infidels. But in a wonderfully short time most of them recovered from the shock and came down with their men into the school. The men, on the whole, felt important and rather pleased. Somebody was taking notice of them, and thought it worth while to show them strange things, such as the cleaning of rifles and the aiming of the same. They were willing to learn - even keen. The officers were given books and soon knew enough to teach the men.

Their methods on parade are not ours, but then we have not got Abdul to cope with. To draw attention to any faux pas in the ranks the native officer will cast stones at the offender, who stands conscious of wrong but outwardly unharmed, whilst the shins of his neighbours bear his punishment. Or on a particularly hot day the wrong-doer will be told to run.

"Whither, O Yuzbashi?"

"Anywhere, and with great speed."

![]()

157

So the half-fledged gendarme starts at a shuffling double for the edge of the parade-ground, to be ordered back when he gets there, "with greater speed than before." He arrives blowing and perspiring at the unwonted exertion, clutching his dangling bayonet and unstable nether garments, and wishing that stone-throwing were the only punishment adopted by the authorities.

Christian gendarmes are a failure. They are not used to carrying arms, and life-long subjection to the Turks has made them unfit for a post of authority. In time, when the body is a force, they may be possible.

At first it was made something of a point by the Powers that Christians should be used, and Hilmi Pasha, the Inspector-General of Reforms, obligingly sent one to a remote Turkish village to quell a disturbance, since when, I believe, nothing has been heard of him.

In their districts the British officers were looked upon by the population as judges and fathers, and Colonel Fairholme, Commandant of the contingent, was constantly besought by the citizens of Drama to settle their domestic differences. The Turkish Act - or whatever it is - under which these officers serve, forbids them to do anything but technically-instruct gendarmes, but gradually by natural evolution they found themselves practically "running" the towns in which they were stationed. The rescue by Captain Hamilton of a wrongfully-imprisoned Greek at Kavala gained for him great kudos among the Christian inhabitants of that port. A man

![]()

158

with a head, who could be depended upon, was such a novelty that the big birds of the various neighbourhoods, as well as the ground game, flocked to them for advice. All this time they strove with the gendarmes till by-and-by these began to feel conscious of a backbone, and to do things off their own bats.

A notorious Kavala thief was caught in the act one day, and took to the sea in his boat. After him followed one of the new-made men in another boat, and several inhabitants. As the thief tried to pick them off with a firearm these last dropped out of the hunt and the man with the backbone pulled on alone, under fire. Getting within speaking distance he called on the thief to surrender, and this being refused, shot him dead. For this act of duty the gendarme was imprisoned by the Turkish authorities, and freed and subsequently promoted by the British. All of which had a great and desirable effect on his brothers-in-arms and the populace of those parts, who saw that the New Gendarmerie was for practical use and protection.

There are still plenty of brigands left in Turkey, who live, according to the time-honoured custom of their profession, by robbery and blackmail. It is a life which especially appeals to the sporting instincts of the Albanian, and the most prominent little coteries are composed of these dashing gentlemen. An Englishman in Salonica was so unfortunate as to own a large farm in an unfrequented part of the Monastir district. Upon this rural retreat descended periodically a congregation of

![]()

159

The old and new gendarmerie

![]()

160

brigands on business, who made themselves a settlement on the property, and discouraged argument in the usual manner. The chief, a man of great culture who could read and write, then indited a letter to the owner in Salonica naming the exact sum which would tempt him to leave for home, and hinting in a postscript his misgivings as to probable barrack damages in the event of said funds missing the post.

"Why don't you get the Government to send troops up and clear themn out?" asks the simple stranger.

"Because, my dear friend, they would disappear before the troops arrived, and reappear the moment they left."

At odd intervals a few brigands are netted, and housed in the Bias Kula on the sea front, where they can be seen peering between the bars of the narrow windows, with dingy soldiers sprawling against the wall below them and squatting on the roof above. The most successful way of dealing with a chief is to give him a high post - such as Collector of Customs, with the chance of gathering in his salary departmentally, and thus make it worth his while to keep quiet. Several notorious brigands are now enjoying life in snug Government billets under a wise Sultan.

Every European country of importance owns a Post Office at Salonica, which is considered - like the Consulate - a part of the country to which it belongs. The English mail-bags come out of the train or the mail-boat straight into the office, only

![]()

161

the parcels being subject to a Customs examination. The outgoing letters bear English postage stamps, and are date-stamped "British Post Office, Salonica." As it seemed that letters might go to any of a round dozen of offices, we also visited the Turkish, French, Austrian and a few more on the off chance, and sometimes ran an odd letter to ground in one of them.

Our hotel was a most scrupulously-managed establishment, as may be gathered from the following instructions for the behaviour of its guests, translated from the French:

I. Misters the travellers who descend at our hotel are requested to hand over any money or articles of value they may have to the management.

There is a frankness about this which almost robs it of its sting.

II. Those who have no baggage musi pay every day, whereas those who

have it may only do so once a week.

III. Political discussions and playing musical instruments are forbidden,

also all riotous conversation.

IV. It is permitted neither to play at cards nor at any other hazardous

game.

V. Children of families and their servants should not walk about

in the rooms.

The choice of crawling along the floor or being

![]()

162

carried by the families is thus left to each servant's individual taste.

VI. It is prohibited to present one's self outside one's room in

dressing-gown or other neglected costume.

X. Travellers, to take their repose, [Repos, an

obvious misprint for repas.] descend to the dining-room, with

the exception of invalids, who may do it in their rooms.

XI. A double-bedded room pays double, save the case when the traveller

declares that one bed may be let to another person. It is, however, forbidden

to sleep on the floor.

Having added a twelfth commandment as to the penalties attached to drinking soup out of the soap-dish or throwing the wardrobe out of the window, we proceeded to break the third enactment in all its clauses, and the banjo did what she could to assert her independence.

The best thing about Salonica was the bathing. In those windless days the town was a stew-pan. Under the merciless sun, a thick soaky heat filled streets and houses, and the only escape was in the cool outer water of the bay. The same old Jew-boatman each morning pushed away at his oars till the green awning-shaded boat was out past the mole, and then overboard we went. Swimming out into the bay the first time, I saw a white cloud above the horizon, and over it - a shade bluer than the sky - a faint white-laced peak, so intangible as to seem a part of the cloud. It was the very

![]()

163

home of the gods - Olympus. Unconnected with sea or earth, its peak hung poised in the sky with the sun shining through the haze on the snow.

In the inner bay lay one of the toothless leviathans of the Turkish Navy. She was officially described as a battleship, but report denied her either guns or engines that were anything but scrap-iron. For years she had swung to the same moorings; no smoke had curled from her funnels, and no European had been allowed on board of her. Now and then a boat came on shore from her, its crew turning their hands forward instead of backward to feather - Turkish Navy-fashion - but what they did on board none knew. No shore-boat was allowed to approach her.

She lay perhaps five furlongs from the mole, and what was more simple than to swim off, leaving one's boat a couple of hundred yards away, and to arrive in an exhausted condition at the bottom of her side-ladder? So far, so good. The sentry, entirely taken in by the palsied clutchings at the grating and the raucous breathings, allowed the fainting swimmer to draw himself up a few steps of the ladder. After a breathing space the naked humbug staggered to his feet, and gazing under his hand for the erring boat, which was under his nose, mounted a few more steps to get a better view. At this point the sentry's humane instincts were overcome by his stern sense of duty, and he advanced to the top of the ladder, waving the unauthorised person back. The wet one - now seeking his boat on the most distant horizon - care-

![]()

164

fully saw none of these signs and backed up the steps till his skin met the scandalised guardian's outstretched hand, who raised a furious voice in protest and brought his fellow-minions on a dead run. This seemed the time for the dignified retirement to begin, but before he bowed to superior force the explorer was rewarded by the sight of a wedge of deck and an undeniable gun of the Hotchkiss type, though whether it worked he can't say from a superficial inspection. The people in that ship were most disagreeable, and came out with rifles and things, besides using uncalled-for language to the boatman when he picked up their late visitor under the stern. They made poor old Isaac quite nervous.

One afternoon came the news we were waiting for. We were drinking tea in the most comfortable house in Consulate Row with the three merry men its inmates, and the Man in Authority had had a telegram. At Koumanova, near Uskub, there had been a fight and twenty-four insurgents had been killed by Turkish troops. How much was fight and how much slaughter was unknown. The insurgents were supposed to be Servians. But whoever they were there was something to go and see about, and prospects of more to follow, so the next morning we presented ourselves before His Excellency Hilmi Pasha, Governor-General, for permission to travel in the "Interior." The worthy Pasha had not much to say to us, possibly because Moro had called him a liar in one of his last year's articles, though most Turks would consider that a subject for pride. We gathered that the Interior

![]()

165

was in its usual state of blissful calm; that the repatriation (horrible word) of refugees was going on under the most happy conditions; that all their wrecked houses had been or were being rebuilt by the Turks and made nice and comfortable for them; that there was no such thing as an insurgent in the country, and finally, that deep peace brooded over all.

"We have their word for all these things,says the Bard. We told his Excellency that for the moment the one wish of our hearts was to behold this happy homecoming with our own eyes, and put to shame the ill-natured British newspapers that doubted. Of course, like a true Turk, he walked round and round the question. We had heard it - anyone would tell us - what need to go? It was dangerous - even uncomfortable. Bad hotels, - fevers - brigands - captures - ransoms! (Would nothing choke off these obstinate mules of mad English?) Well, then, it was not in his power to grant such a permit.

No doubt their words are true,"

"Higher authority - Constantinople - no answer for weeks..." And there, always indefinite, lie left it. In plain English it meant "You shan't have it."

In my childhood's days I was often fed on the salutary saw: "If you can't get what you want, go without."

Putting a slightly different construction on it to that intended by

the author, we did.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]