167

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XI.

Inland among dust, under trees - inland where the slayer may slay him.

OF course there was a rush for the train. Moro at the last moment found he had not packed enough white shirts or dress-ties or some such indispensable, and in the end we were bouncing over the stones at full gallop with three minutes to do a mile in.

At the miserable shed-and-a-half of a station - the end of the line from Paris - country folk sat about on huge bundles, waiting - as ever - for permission to move; green-collared police nosed over printed permits; soldiers lounged with bayonetted rifles at the gates, or jostled without them on the platform; and the railway-staff looked on. Need I say we had forty minutes to wait? At last the peasants and their bundles were hustled into their dens, the soldiers coaxed into theirs; and the train, due to start about half-past eleven Turkish, which was then about half-past six a.m. English, got under way about 7.15 - latish.

The Turks reckon their time from sunset, which they call twelve o'clock, and consequently if a Turk tells you something happened at half-past ten at night some years ago, you have to get an

![]()

167

almanack to find out whether it was really half-past two or five o'clock a.m. Time therefore goes a great pace in the Autumn and very slowly in the Spring. If a Turk is late for dinner in November he has only to say "I'm awfully sorry! My watch is the day before yesterday;" which is held to be a perfectly valid excuse.

The normal state of Turkey is stagnation, and everyone who wants to move about must expect work. So long as he sticks to the railway-line a man may start with no more trouble than having his name, profession, age, size, colour of hair and eyes, shape of nose, mouth and chin, and detailed intentions entered on a beautiful document all over wriggles and flourishes called a teskari - to be shown at all demands - and the inscribing and official stamping of his own passport with the name of the town he proposes to honour with a visit. But if he is allowed to leave the railway and penetrate that mysterious "Interior," he will not be let off with such a mere glance of recognition as this. Means will be found to label and classify every inch of him, and to define every foot of his progress, and that he may not deviate from his appointed path guards of honour will compass him about, and take particular care that he shall only look where he ought to. Our teskaris, without which we should not have been allowed to get into the train, franked us as far as Uskub on the main line. Once there it was our business to find a way out.

The line goes up the valley of the Vardar; over the bare levels - along river banks fringed with

![]()

168

acacia and willow - through deep gorges and rockarches topped with green, out into a fertile country of waving cornfields with grey hills behind.

At every culvert and corner on the line was a bit of thatch on two sticks and a ragged figure presenting arms beside it. The insurgents were putting in a little casual train-wrecking in their off-time, and these posts were there to interrupt them. At the baked country stations we bored through the throng of soldiers and people to buy salty sausages, and a draught of cold water from the red earthen pitchers in a row by the railings. More troops got in at every station. At Kuprili, half way up, a company of Albanians boarded the crowded ovens in the rear of the train, tumbling in - twenty deep - with yells of laughter. At another place a guard of honour presented arms to a little creature with bent back and a mean face. Gorgeous in Russian army cap, white jacket and gold buttons, he answered the salute and picked his way to his reserved carriage. A Consul in full fig! The worst thing about him was a pair of horrible imitation butcher-boots made out of shiny spat-leggings over bad shoes. Behind him towered a huge Albanian Kavass in the white kilt of his country, bristling with knives and pistols to protect the Civil Servant of the Bear.

In a thunderstorm and heavy, glorious rain we made Uskub about two o'clock. Passports promptly annexed by the police.

Gardens and white houses near the station, and close-packed wood-fronted boutiques round the

![]()

169

market and the old town. From our bedroom at the Hôtel Turati we looked across a wide deserted cemetery, unwalled and meshed with footpaths, where starved dogs howled mournfully all night.

In the salle-à-manger were the Austrian officers of the Turkish Gendarmerie. Their colonel was a hawk-nosed, hawk-eyed man - a martinet. One of them, who had lived in a Bloomsbury boarding-house, discussed Hungarian horses in good English, and by degrees was drawn to talk about the matter which had brought us there. It happened at a village four hours away. He and his brother officers had missed the affair by an hour, but thought it was a square fight. The villagers - Bulgarians - of course knew nothing of the dead insurgents, but swore they were Servians. The village was full of Turks - he didn't know how many - and they had fought all day. The others had used dynamite freely.

Officially those Austrian men were not popular. Their country is stretching out tentacles over Albania and Western Macedonia, ready to grapple and hold fast when the excuse comes, and is making itself a soft couch ready to lie on. The Turks don't like it, for obvious reasons; the Albanians don't like it, having no desire to be grappled; the Bulgarians and Servians, both very thick at that corner, have other ideas as to the parcelling out of a free Macedonia, and they don't like it at all. In spite of its spending powers the Austrian propaganda is distinctly unpopular; and the officers, who were hardly put there merely to drill gendarmes,

![]()

170

shared its odium and stood a very good chance of getting shot by one or other of the dissenting parties. The colonel actually was shot not long afterwards.

Up the road, at the new Roman Catholic Church (kindly built by the Austrians), a crowd of gala-dressed Albanians gathered one morning for the feast of Corpus Christi. After the service in the Church a procession wound round the churchyard singing, and kneeling at a shrine in each corner. In front walked a company of pretty little girls, some in white - some in Turkish shalvas [Loose trousers.] of crimson or green, and sashes of brilliant colours. They threw flowers before the priest and laughed at the sunshine and the fun of it all. The women - most serious - bent their white-draped heads over their books or held a dribbling candle away from their Sunday clothes. Their black skirts were short enough to show checked or speckled shalvas, white ankles and bulky shoes. When they knelt the unbending crinoline thrust its covering into black roofs and mountain peaks round the devout body. In the fore-front of the battle Colonel Hawkeye and his officers carried candles for the good of their country with conspicuous gallantry.

Over the Vardar bridge streams of ponies and ox-carts poured in to market. Cross-legged between two bales of charcoal sat an old Bulgarian, swaying to the motion of his pony. As the little hairy animal pit-patted past the guard-house at the end of the bridge, the sentry rolled forward,

![]()

171

stopped and questioned him, then dragged out a handful of charcoal from his load and sent him on his way.

The Turkish soldier takes toll of any Christian property he chooses. I have seen a peasant arrive in a town with a great pannier of cherries, and by the time he reached the market he had hardly a pound left to sell. Every second soldier in the street took a fistful as the pannier

![]()

172

passed, and two or three times he was made to turn out the whole lot by the roadside in a search for imaginary contrabrand.

On a sloping, uneven spread of ground at the eastward end of the town, the goods and chattels, carts, oxen, ponies and paraphernalia of the market-folk were gathered. At the side and back the bare-trodden hill went up to barracks, and in the hollows the brown-jacketted Albanians argued and punched thin cows, or watched sore-backed ponies careering up and down, manes and tails flying and heads jerked in the air by the heavy-fisted urchins who "showed them off." Make and shape go for nothing - the healthy-looking pony is generally a hopeless slug - and no Macedonian wastes time feeling legs or studying shoulders. "Let's see him move" is the only demand, and away goes the terrified little spindle-shanks at 2,000 feet-seconds muzzle velocity. Buyer and seller wag hands over their bargain as our folks do at home, and then repair to a kiosk where the Turkish official relieves the late owner of ten per cent. of the purchase-money. For five or six pounds you could get the best pony in the district. There were some useful "packers " to be had for four.

About the hour of sunset we were plodding up the hill to examine as much of the barracks as might be seen without over-exciting the inhabitants, when a distant sound like the deep voices of many aged sheep, punctuated with a measured thudding, stole on the stillness of the scented air. From behind a house emerged a gang of men blowing

![]()

173

into large brass instruments, followed by the youth and beauty of a regiment of Anatolian Redifs. [Reserves.]

Anatolians.

At the bottom of the hill the martial melody ceased out of regard for the lungs of its producers, and the column marched up the hill past us. I have seen men in different parts of the world who might claim to be ugly, but as those people passed it seemed to me that every man of them was uglier than anyone I had ever seen before. Some of the sergeants had evidently been through a course in the German Army, and strutted with pointed toes at the German parade-step. Outside

![]()

174

the barracks the battalion halted and turned into line, after which the companies were inspected and unblushingly reported "all correct." On this comforting assurance a brief but terrible braying burst from the band, said to represent a piece of the Hamidi march. This was speedily hushed, and the entire regiment raised its raucous voice in a shout of "Padisha chok yasha," which means "May the Sultan live many years." Twice were these orchestral and vocal efforts encored before the performers were allowed to retire indoors with the satisfied air of having done sufficient damage for one day. Every garrison in the Empire parades at sunset to go through this ceremonial.

It is not easy to take a Turkish band seriously, but I have met one or two which were not beyond the bounds of reason. Even in these the instruments - nearly all basses - differed widely in pitch, but behind the out-of-tunanimity there is a strong, unique character in their music. Generally in a minor key, it is weird, grim and full of evil foreboding. If one imagines it as incidental music in a melodrama (which means drama with music, and not a blood-and-thunder absurdity), it must inevitably herald the coming of the tyrant - a cunning, cruel power that crushes its people. Pompous it is, in a sense, but there is no grandeur in it, nor any suggestion of soldierly vigour and dash. To a Turk it may possibly be inspiring; to a European it is - even when properly played - forbidding.

The national ballads - love-songs and such likeso far as I have heard them, are, as music, frankly

![]()

175

incomprehensible. But for quintessence of heart-breaking torture I recommend to you one of these on a gramophone, such as I have heard turning the air sour in the streets of Salonica. Death on the rack is an inadequate punishment for the perpetrator of this horror.

There lived in Uskub a prominent man with a considerable knowledge of the district and its little ways, in whose comfortable den we foregathered by night, imbibing beer and much wisdom. We two sat in easy chairs whilst he walked up and down in the tobacco smoke and recounted stories of dark doings and the ways of men.

"And that, let me tell you, is a thing that happens every day." Then with a quick lift of the hand - "Incredible!"

Trouble, it seemed, was in the air. The comitajis, in spite of the efforts of the Central Committee to keep them quiet, were on the move, and an outbreak was expected all over that district within a month.

He was a restless man, much given to riding about the country alone, which in those parts is not a healthy thing to do. Besides political enemies, there are plenty of people who would slit a throat for half-a-crown. On one of these rides, at Koumanova, about four hours away, he had come across a crowd of Bulgarians, limping and hobbling. In a khan [Inn.] hard by were more, unable to stand. One - a schoolmaster - told how they had been dragged over from the village of Ptchinia by Turkish

![]()

176

soldiers. A few days before, he said, a band of insurgents descending on the village had murdered a Turkish official and made off into the hills. The Turkish troops sent to punish the insurgents, instead of following them, had flung themselves upon the villagers, dragged them into the open, and beaten them with sticks "three fingers thick" for several hours. The miserable wretches - hardly able to crawl - were then dragged ten miles to Koumanova.

Some of them showed their battered bodies to the visitor, and their calves, thighs and backs were raw and swollen. After he left they were flung into prison. This is a perfectly authentic case, and a typical one.

It was at this village, Ptchinia, that the fight took place in which the twenty-four insurgents were killed, and it now seemed probable that they were the original offenders who brought down this visitation on the inhabitants.

As the smoke thickened the talk ranged round Wagner to the cliffs of Cornwall and back to Macedonia. Then we confided to our host something of our general idea, and gathered points as to its possibilities. To drive by way of Ptchinia to Egri-Palanka on the Bulgarian frontier, a two days' run, was the first project. With luck, it appeared, this might be done.

"There may be some wandering Albanians in the hills, and they might have a shot at you."

"I see. Well, what do we do then?"

"Oh, don't take any notice of them."

![]()

177

We promised to preserve, as far as possible, an air of indifference.

"Got pistols and that sort of thing? Tlat's all right. You probably won't want them, but it's better. Oh! and take some grub with you; nothing eatable on the road. Well, I hope you'll get through - good-bye."

There were a lot of earnest patriots about, of one sort and another, and the "sporting set" at Uskub are broadly impartial about whom they stick knives into, so it was the will of the friendly man to send an armed servant home with us to scare them off.

In the bare hotel bedroom, far into the small hours, we sprawled over the ricketty table, balancing the grease-clotted candlestick on a map of the Balkan States which embraced everything from Buda-Pesth to Athens on a scale of thirty-five miles to the inch.

Sitting here in London I am measuring off with a halfpenny on that travel-worn old rag a straight three inches that takes in the whole of the hundred and fifty miles or so of our projected journey, but this little map did all we asked of it on that trek.

A grand, cool night that was, as different from those sweltering nights at Salonica as Heaven from Hell; you could breathe and think up there among the hills. So we proposed and discussed and rejected, and got up to throw stones - we kept a little heap in the corner - at the dogs outside, and lit pipes and wired in again. Moro, the old hand - the man who had been at the game of Turk-bluffing

![]()

178

before, and knew all their moves by heart - showed his untaught brother how to play. There is skill in the game, and the first rule is silence. The others are to move quickly and keep on moving.

To get out of the town a carriage is needed, but to order that carriage too soon is to allow the driver time to tell the police, and the police time to demand teskaris, and so end the journey before it is begun. Therefore every detail must be prepared and ready, every possible event foreseen, before a whisper leaks out. When the cocks began to crow and the candle died with a splutter the plan was complete.

The first thing to be done next day was to find an interpreter. He must be a Christian, or he would give us away to the Turks; a pliable man, or he would object to being hauled about without warning; strong in the body, or he would collapse on the trail. Our luck was in, for we met in the street a Bulgarian, bred in the hills, with a good knowledge of French and, of course, Turkish. He was looking for a job and found it at once.

A greater scribe was once advised to "buy an 'am and see life," and the first part of this injunction we proceeded to carry out faithfully, that the act might in natural sequence enable us, as it did him, to fulfil the second clause. Baggage and equipment were cut down to:

Moro: - Pyjamas, extra shirt, collar, pair of socks, toothbrush, comb and razor, rolled up in a light rain-coat; pistol and camera. Self: - Extra shirt, pair of socks, shaving-brush, toothbrush, soap and writing-paper in a haversack; pistol and camera.

![]()

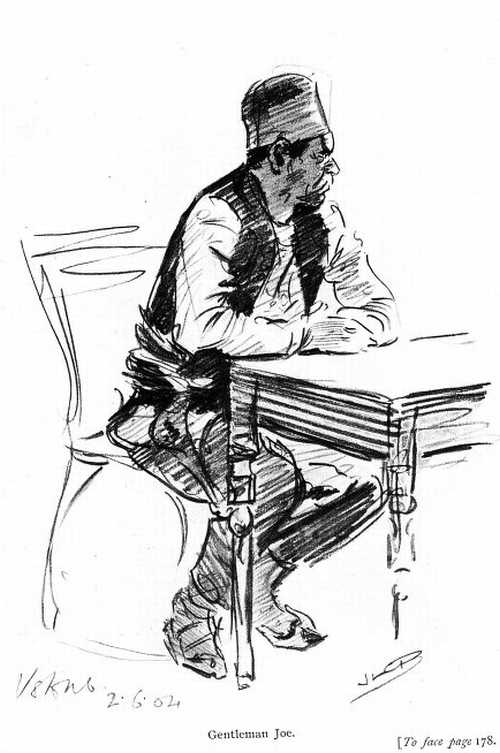

Gentleman Joe. [To face page 178.]

![]()

179

It was decided to travel in ordinary trouser - suits instead of breeches to avoid attracting attention.

That evening the interpreter, whose honoured name was Alexander - shortened to Sandy - was allowed to know that we were going for a little drive in the country, and bidden to find a carriage, drive a bargain with the coachman and tell him that we would start at six in the morning for Koumanova. Thus, in case the Jehu, between dark and daylight, should find time to chat with the police, they would be all ready for us on the road we were not going by. For another thing, Koumanova is on the railway and therefore was less likely to arouse suspicion.

Everything went like clockwork. Sandy, fondly imagining that he would be back the same night, asked no questions. At half-past five in the morning, and not till then, did we enlighten the hotel people, demand the bill, and order the baggage to be sent to Salonica. At six - marvel of marvels - the rattletrap was there with three white Weary-Willies to drag it, decked with blue bead necklaces and ropes of bells. The blackguard-looking jarvey was promptly christened "Gentleman Joe," and ordered to abolish the bells, the same being the outward and oracular sign of a journey into the country. So far no green-collared gentry smelling after passports.

With a heavy affectation of unconcern and a wary eye up the road we climbed into the carriage, and started with a nerve-shattering rattle. The intense desire for silence magnified every rap of

![]()

180

the horses' hoofs into a signal of alarm conveying the news to the whole town:

"Run-and-catch- 'em!No flying battalions, no keen-eyed posses of police swarmed down upon us, and we passed out of the town. A sleepy sentry, yawning for the relief, was the only sample of dread authority. Over a hill we dropped out of sight of the roofs and into the open.

Quick-quick-quick-quick!

Move number one had come off.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]