241

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XVI.

Till these make laws of their own choice and Judges of their own blood.

CAVALRY of the Line and Mounted Police divided the honour of keeping us out of mischief. The troopers are the only Turks who do not wear the fez; their head-dress is a little astrakhan cap with a gold lace cross on the crown, and their shoddy clothes are black with red facings. Tight black trousers disappear into loose cavalry boots, and spurs are optional - one, two, or none, according to taste. A sabre in a dented scabbard banged their left heels, and a "Martini" balanced on the front pack. They sat their Russian saddles with instinctive grace and handled their little well-bred horses like workmen.

The police had evidently been dressed at a sale of old stage costumes, flung among them in a hurry. Most of the jackets had yellow braid on the front, and some of them were large enough to meet over the chest. Brief trousers of many colours clung to their thin shanks, and white wool stockings or bare ankles pummelled the flanks of their hairy ponies.

The entire outfit was under the command of a

![]()

241

town - police officer, for whose authority the cavalrymen showed an elaborate indifference. They were the sort of rollicking men-at-arms one meets in Mr. Stanley Weyman's novels, and were continually skylarking with the more sober-minded gendarmes, whom they held in good-humoured derision.

One of their most pleasing tricks was to pass a

![]()

242

policeman at full gallop, and with a cunning twist spin him out of the saddle. This game of Looping through Space was accepted by the police as a necessary part of escort-duty, which it would be bad form to resent. At odd times the spirit moved one of them to ride hell-for-leather at some yelping cur, with brandished sword and blood-curdling war-cries, till the dog escaped, when he lopped off the branch of a tree and returned quite happy.

The first day's trail, a mere sheep-track, lay over big stony hills where a cool wind blew across the cloud-shadows, dropping in the afternoon to a brown stream bubbling over pebbles, where the green closed in overhead and there was only room for single file. In this valley it was that Miss Stone, the American missionary, was captured by the insurgents. She was travelling with a party of Bulgarians and without escort, and was therefore easily seized and carried off into the mountains, where for months she was held to ransom, which arrived eventually in the nick of time.

A couple of hours before sunset the roofs of Raslog showed up - Mehomia, the natives call it - and the ponies splashed down its long empty street-running water from wall to wall. Under the eaves of the mud-houses stuck out round earth ovens, but no smoke rose from the cold chimneys. The town was deserted except for a few shop-keepers, and soldiers who lived by hundreds in the best houses. A year ago the Bulgarian population had vanished before the advancing troops, and very few had dared to come back.

![]()

243

Alexander, cooking supper at the khan, had some conversation with a Bulgarian schoolmaster, who under pretext of carrying up the food passed into our room and told a story of robbery and outrage by three soldiers that afternoon. An attempt was made next morning to visit the house where the affair had occurred, but in spite of the most artful dodging up and down back alleys we could not shake off the police, the presence of whom drove away all the pedagogue's nerve, and the quest had to be abandoned.

At the khan appeared an officer who had commanded the escort which brought up Miss Stone's ransom. This worthy, amongst others, was hood-winked by the missionaries entrusted with the paying over of the money, and was left to guard empty treasure boxes to keep him and his warriors out of the way. Had this not been done the ransom would never have been paid, as the insurgents who received it would not approach the appointed spot so long as the troops were on the qui vive. Moro had gathered the truth of the story from the missionaries, but the little captain when he told his version had no idea how he had been "done in the eye," and for various reasons we did not enlighten him.

Pushing out of the town along a watery valley we passed Bansko, the little village where the ransom was paid, backed by a gaunt grey hill, with snow-peaks standing round; a network of brimming ditches kept the ponies stumbling and jumping for two or three miles. Boring up into

![]()

244

the hills the procession got into thick bush and some very stiff, prickly whins, which so tickled up the ponies' legs that they decided to stay where they were. It was not possible to hit them from the saddle, as they were protected by a stick-proof armoured belt of sacks, rugs, bags and gear, so they had to be encouraged by an active peasant behind with a hedge-stake. This member made rushes at unexpected moments and laid on a hail of blows backed by leonic roars intended to strike terror to the animal's heart.

At a pig-haunted village the cavalcade bestowed itself on three-legged stools for refreshment, and here Sandy was bidden to discover secretly of the innkeeper at what point the trail turned off to Kremen. Kremen had been sacked by the Turks the year before, and they were expected to be rather shy about showing it off, so nothing had been said about visiting it. The landlord cocked his eye and gave the bearings.

Two miles up, under the oaks and beeches, Moro and I with a twenty yards' lead turned off the main trail to the left. The voice of the police-officer rose aloft; then that of Sandy proclaiming that this was not the route. The answer was a flippant one, and being translated to the Turkish contingent, was followed by their combined protests lifted as one. Down the trail after us rode Alexander - a transmitting-station for the flashes of rhetoric from the group at the corner. Hunting the opposite hill-side for the village, Moro and I were laying odds on the crowd rounding us up and herding us

![]()

245

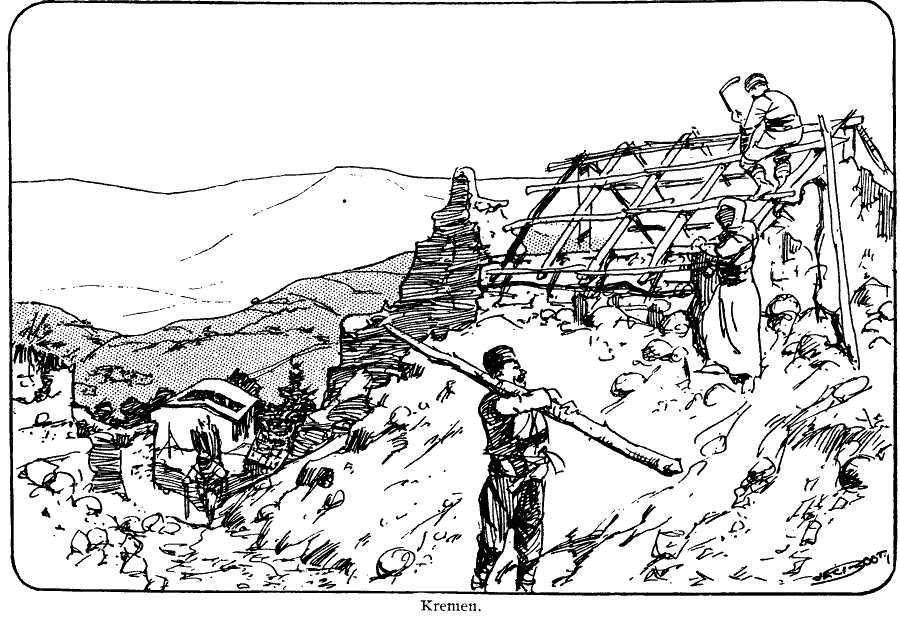

Kremen.

![]()

246

back to civilization, and if there had been a soldier in command I think he would have done it. But "no reply to urgent message," and they caved in and followed us.

Three miles further some strange heaps of rubble lay piled on each side of the path, and we were riding on a thickness of smashed tiles. This was Kremen.

Scrambling to the top of a heap of earth and stones one got the full effect.

Shapeless wall-shoulders stood out of the mass, and the end of a charred beam pointed drunkenly into the sky; all down the hillside below the loose piles bulged and the empty, shorn walls gaped; no sound came up from the crushed houses - no figure moved in the choked streets, hardly traceable in the general level of rubbish; everywhere was desolation and black ruin. A hammering began somewhere in the wreckage, and we climbed over the mounds towards the noise.

On a skeleton roof of rough-hewn poles sat a Bulgarian putting together his new home on the site of the old one. He had managed to build up his shattered walls a foot or two above the jumble of earth and stones that buried them, and with the help of a few of the old timbers - charred and blackened - he hoped to have a roof on in a couple of days. The sight of the Turks with us made him ill at ease, and he objected to being sketched.

Across the valley the green bushes had grown over the crippled walls and half hid their deformities.

![]()

247

At the bottom of the hill was the church - the only building in the place with a roof on - and that had a big square hole in the middle. Round the building a few little shanties had been knocked together, and under these squatted two or three old grizzled men, a box before them for a table, and on a bark shelf nailed to the wall their lares and penates in little heaps. They rose and offered us the shelter of their humble home, producing - poor things - the most terrible leathery cheese, which of course we had to eat.

Alexander was sent among the hovels out of reach of the Turks to discover whether the wretched people still had the money Mrs. King-Lewis had distributed to them, and found that so far none of it had been taken from them; the average grant was about £2 each. From some of the returned exiles, lured into a quiet corner, we learned how the village had been destroyed.

A year before, it seemed, a band of insurgents from Bulgaria had been lurking in the neighbourhood and no doubt had come to Kremen for food. The people were accused of having harboured revolutionaries, and a body of troops arrived to execute vengeance on the village, which was not done in any haphazard fashion, but deliberately and with fore-thought. The troops brought with them ponies carrying tins of petroleum lashed to their packsaddles, which were unloaded, and the soldiers, producing squirts, soon covered the walls and roofs with the spirit. After each house had been thoroughly sacked the tins were emptied upon

![]()

248

piles of bedding and the whole village was fired at a given signal. Lurid descriptions of the usual horrible scenes followed - old men brained whilst trying to protect their daughters; women's hands cut off and their children murdered before their eyes; outrage, pillage, and massacre let loose. Truly the Turkish soldier - quiet enough in peace time - is a demon out of hell when the lust of blood is on him. The police-officer and the escort had the decency to look ashamed of their countrymen's work, and made no effort to hide the worst evidences of it.

Kremen is only a sample. The countryside is thick with the ruins of Christian villages stamped out in the same way, with the same old weary details in every case. There is nothing new in it all - it did not happen for the first time that year nor fifty years before. It has been going on for centuries, and always will go on until the Christians in Macedonia are given the right to live a freeman's life and the power to uphold that right by the only people who can give it - the Powers of Europe.

The sun-speckles fell through thick hazel leaves on to a narrow, wriggling path, and the low branches swept the saddles, so we had to lead. In the green frame ahead the width of the Mesta river lifted, rolling down a deep valley to the AEgaean near Kavala, and a ledge, sometimes no more than two feet broad, carried along its cliff banks a hundred feet above the grey-green water. On the rock-pinnacles above hung little watch-towers, mostly deserted; from one of them two sleepy soldiers

![]()

249

leaned out and watched us. Later, the banks sloped gently away and great beeches shared the red-leaf floor with the rustling hazels.

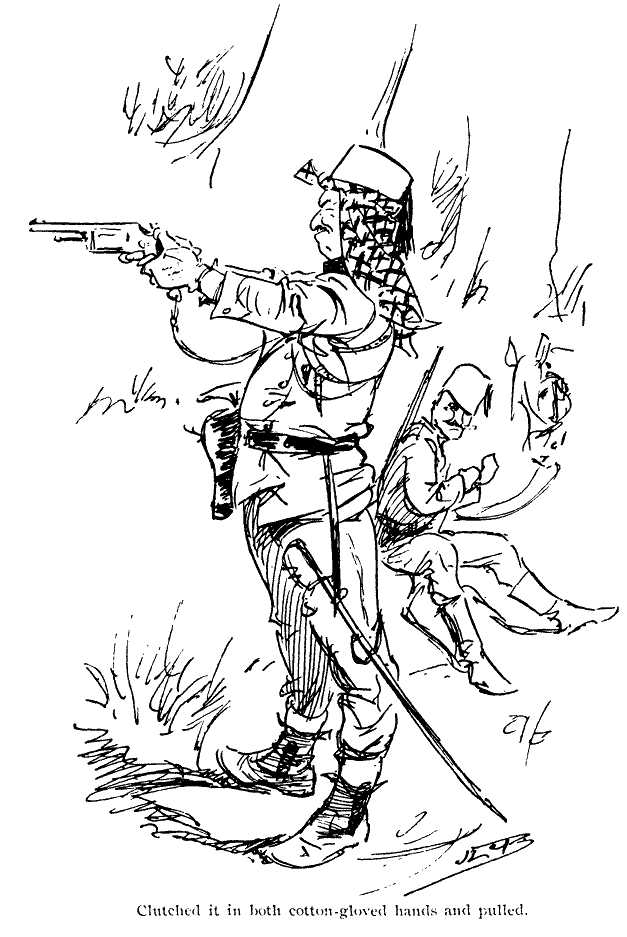

The police-officer stepped carefully in front, leading his pony, as he did not consider the landscape adapted to horse exercise. The most striking item of his travelling costume was a blatant check handkerchief of generous pattern which hung from beneath his fez and kept the sun off his fat neck. The blue uniform - its glories dimmed with dust - was girt about with children's patent - leather belts and his left arm and shoulder were snarled up in coils of green cord - probably meant for binding prisoners. Among his legs dangled a toy-shop sword, his trousers were tucked into sad-coloured socks, and Jemima boots finished the rig. To preserve the lily fairness of his dimpled hands he wore throughout the journey a pair of cotton gloves, in colour a dark white.

Ever since we started he had been working himself into a permanent perspiration in an endeavour to keep cool, and I was surprised when he suddenly turned round and proclaimed a desire for violent exercise in the form of a pistol match. A wide beech was picked out as a target; - to me was the honour of the first shot. I fired at a three-inch bole in the middle of the trunk, and my luck was in. The man of law, hauling out a long nickelly man-slayer, clutched it in both cotton-gloved hands, clenched his face, and pulled. With the report he dropped the pop-gun and wrung his hands, groaning in pain; - Sandy flew to his

![]()

250

Clutched it in both cotton-gloved hands and pulled.

![]()

251

aid. The pistol had fired "très-fort," and he was sure he had let off two cartridges at once.

An amber slip showed on the edge of the beech about twenty feet from the ground, and the damaged marksman pointed to it with a modest smile:

"Aha! - I have hit it!"

"Hit it?" said I.

"Why, what were you aiming at?"

"Effendi! At the tree, of course!"

We bathed in the Mesta, and Moro enjoyed it so much that after he was dressed he fell in again with his clothes on, and we did the last five hours on foot to dry them. The trail was a wet one, and where there was no stream running down the middle of it, water-cuts of uncomfortable width crossed it every ten yards. This was all right in daylight, but before it had been dark half an hour I was dead tired of lying down in them. The path between the streams was four inches thick in dust, so we kept the escort and ponies behind and thus breathed freely. Out of the rice fields in the dusk came the croaking of frogs, and the fireflies glinted in and out of the bamboos and among the dark, scented walnut trees overhead.

A three days' moon just lasted us into the rock-cobbled streets of Nevrokop, and stumbling up to the Konak in the dark we went to sleep on the stone steps, whilst grizzly soldiers came peering with lanterns and the police-officer sought for shelter.

A khan was found at last, but there was no one in; so we broke down the door, tumbled along a maze of galleries and commandeered a room, whilst

![]()

252

Sandy rustled some eggs out of a hole in the kitchen. The police officer, still in cotton gloves, walked about between the beds, admiring two oleographs of a charge of Cuirassiers and the Avenue de l'Opèra. I explained them.

"A-a-ah!" sighed the creaking nuisance, "I wish I were in Paris."

"I wish you were," said I with some fervour, and henceforth there was peace.

Day's trek, fifteen hours. Distance, forty miles.

I was waked at dawn by a great uproar in the stable below. It appeared that a rooster had planted himself on the gallery-rail outside the bedroom and hailed the smiling morn with a vigour which annoyed friend Moro, who flung a boot that missed its feathery mark and hit a horse on the ground floor. The gendarmes, who were sleeping among the horses, thought Shaitan had seized the beasts and huddled together howling "Mashallah!" ["Lord preserve us!"] The ponies soon settled down, and again peace reigned over all.

Breakfast was prolonged by efforts to flip pieces of bread into the gaping mouths of two young storks in a nest on the roof, and a tiny dribbling tap in a petroleum tin on the wall made washing largely a matter of patience. Moro, putting the lid of a cardboard box into his soleless boot on the inner gallery, was able to report progress in the saddling department by glancing over the rail. Just as the cavalcade was ready to march a Greek arrived to take up a collection for bed and board. He

![]()

253

had found the oleographs face to the wall - an overnight precaution against art-smitten policemen - and held himself insulted, so for his own good he was at once shown the difference between and real imaginary insult, and faded away.

A few miles from the town, without reason or warning, a broad paved road began in the middle of the plain. Of course it had never been used, as the natives regarded it in the light of a sacred curiosity which they would not defile by stepping on, and a well-worn horse-trail ran in the dust beside its weed-grown stone slabs. Through the long day's heat we climbed up and bumped down, breaking our own trail where not a goat-track crossed the rocky hills; the one thing of interest was the quenching of thirst.

Towards evening, Moro, bored with the lack of incident, persuaded one of the troopers to lend him his little white Arab. With a multitude of cautions to promener très doucement, he was mounted, whereupon he dug his heels into the pony's sides and shot across the plain, scattering dust and pebbles behind him. Consternation seized the men-at-arms."What now? What is this?"

"Ha! He escapes; - after him for your lives!" yelled Cotton-Gloves, taking his screw by the head and clattering away, followed by the whole trainband with whoops and howls. Moro, in a distant cloud of dust, kept his lead as the chase bounced through a river and on again with waving tails. Waiting between Sandy and myself sat the trooper who owned the flying steed, trying to look dignified

![]()

254

on a pack-saddle, and gritting his teeth as his fierce eyes followed the hunt.

Suddenly the pursuers were seen to pull up in a great commotion, and through their midst burst the fugitive, riding a strong finish. The angry trooper seized his blowing mount as Moro flung himself off, and the flood-gates of laughter were opened. Shouts of merriment clove the air, and at last, to their credit, the ruffled Turks joined in.

That night we lay at a Swiss village made up largely of bell-towers which all gave forth at three in the morning in a rousing carillon chorus "pour reveiller le village," according to Sandy. There was nothing for it but to get up. A friendly old Turkish rag-bag in the street offered us coffee, but gently refused to take a light from my cigarette. He explained in apologetic whispers to the boy that to take a light from a Giaour meant certain descent into the fires of Gehennum after death, which even his constitutional courtesy would not allow him to risk.

Coffee at dawn is allowable, but to be compelled to swallow a thick sugary concoction at mid-day is an imposition. At the most grilling hour of that last grilling day the cavalcade, parched inside and out, drew wearily to a lonely village of the plain. Before we could hide, the local officers were on us, and bore us to their barrack to inflict this hospitable torture on our burnt-brick bodies. To refuse is insult. Heavens be thanked for the mercy of the glass of cold water which always accompanies it!

![]()

255

The well-meaning men were shocked at our "neglected" costume of open shirts, and foretold malignant fevers from the evil airs of the Drama valley. From the saddle this deadly district looked much like other valleys, so we braved its terrors in decolleté and still live.

Miles and miles of barley in a flat plain, and great rarity - a field or two of oats; in their midst an oasis of birches and a clear spring of magnificent cold water. Overhead in the branches shrieked and twittered a flock of starlings, and on the grass in the shade lay half a dozen Bulgarian carriers, asleep by their ponies, swathed to the eyes in immense rolls of rug and blanket. Their foreheads shone with heavy sweat, but they clung to their bedding; - they "feared to catch cold," Sandy explained. The ponies fed with their saddles on - they are never taken off on a journey except at night.

The dusty troopers pulled themselves together for their entry into Drama, and as we trotted over a patch of stubble its minarets pointed up in the distance with the railway line running out behind them.

And so ended the "long trek." Across all its good full days Uskub and the starting-morning looked a long way back, and the mind-pictures of this journey through the Forbidden Land stretched away to the beginning in clear perspective; - a new collection to be added to the old, and studied with strong enjoyment in the smoke of many pipes of peace. In the span of those moving days the heart of Macedonia was revealed to me, and I knew

![]()

256

those things which were hidden from the dweller in cities, furnished

with "reliable statistics." For present needs, we had found the people

coming back; proved the Turkish lies about their rebuilt homes, and seen

their intolerable life, and their weariness of revolt promising quiet for

awhile. With these few facts and the greater knowledge that soaks in as

you go, the three of us came down out of our hunting-grounds in the hills,

with three hundred miles of trail behind us, and jogged across the last

of the open from the whistle of the starlings to the whistle of the train.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]