258

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XVII.

THE DARDANELLES.

Here, in a large and a sunlit land,

Where no wrong bites to the bone.

SQUATTING on the blistering forecastle-head of a little lop-sided Italian steamer, with the island of Lemnos on the quarter, a cheery horde of young Albanians worried round the wonderful belongings of the stranger in their midst. Two lean, cropped heads were bending over the camera and admiring a portrait of the sky in the finder; behind them a white-capped warrior of twenty took a miniature view of the deck-seams through the wrong end of the field-glasses. Lithe, tanned fingers strove to roll a pinch of unyielding "Pioneer" into a cigarette, whilst the stranger accepted a gift of the native birdseye and drew the hot smoke through a briar pipe.

The careless, high - spirited youngsters - two hundred of them - were being taken to Constantinople as recruits for the Sultan's Bodyguard, and as their drawing-room manners had been a little neglected in their mountain homes, they were

![]()

258

causing acute anxiety to the captain and officers of the old packet, who had made elaborate preparations for quelling them with hot-water hoses and suchlike superfluous objects. Puzzled at the stiffness with which they were received, they welcomed a friendly-disposed visitor bearing tobacco and magic boxes, and made me free of their buzzing camp in the bows, thrumming at nightfall on two-stringed lutes with weird songs in tremolo.

Excitement over the "Malacca Incident" of 1904 was at full blast, and there was talk of the Russians taking the captured steamer through the Dardanelles; so here was I, on the off-chance, lurching down to the Straits at ten knots an hour.

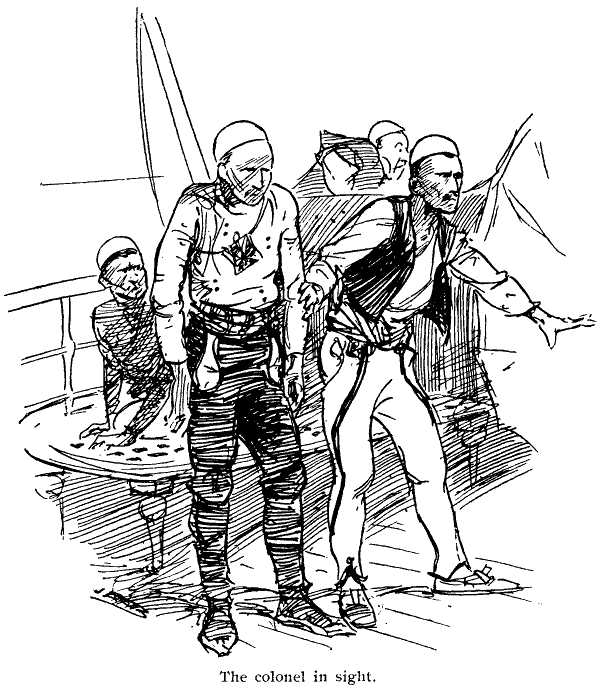

The poop was inhabited by one or two elderly Turks with honourable beards and well-filled harems. The budding guardsmen, in their search after knowledge, spread themselves all over the ship and interfered with the privacy of these family circles. Shouldering past the wrathful husbands, in gleeful clusters they pulled the canvas jacket off the wheel and rejoiced over its brass fittings; in awe-stricken groups they listened, spellbound, to the spirit-voice of the Cherub log clinking on the taffrail. But these joys were forbidden, and the Second Officer hastened to reprove them, whereat they played push -ball with him in their own boisterous fashion. He escaped collarless, and scuttled below for their colonel - the only man on board for whom they cared a button. This stern parent, emerging from his bunk in a baggy sleeping

![]()

259

suit, had only to show his eagle nose over the ladder and his naughty children, cowering behind sky-lights and benches, doubled back to their forecastle with temporarily chastened spirits.

The colonel in sight.

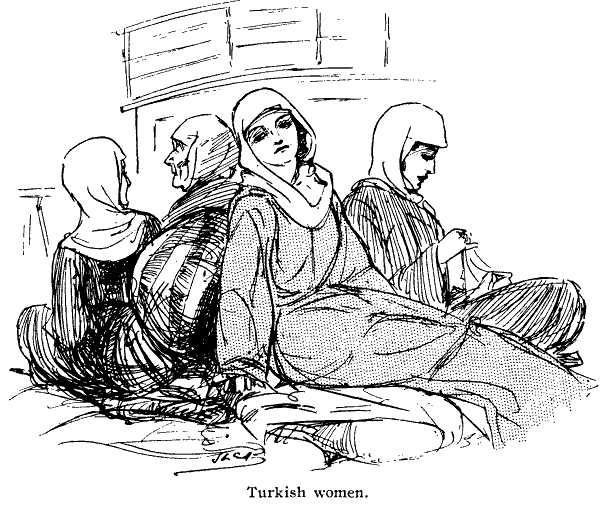

On the hatches of the well-deck was a bivouac of Turkish women. On board ship they do not

![]()

260

mind showing their faces, and some were well worth looking at; - small features and big dreamy eyes, with little well-formed mouths and sometimes a black curl showing under the white yashmak. Going always veiled they have sallow complexions, but the pallor suits their beauty. Young girls, handsome women, and the old crones who looked after them sat together on piles of bedding and coloured rugs, without occupation and saying little. They seemed to look sadly on life, and truly it holds little for them.

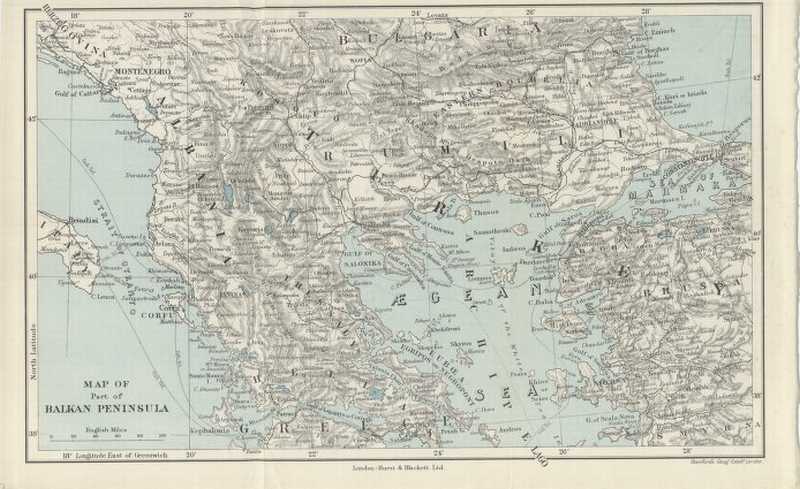

Forging through the ultramarine water we turned the ancient fortress of Sedil Bahr - the "Old Castle of Europe" of long-dead mariners - and pointed into the narrowing Straits.

On the European shore, bare, bush-dotted cliffs; on the other side, behind the windmills and the hump of Achilles' tomb, the Plain of Troy goes back to green foothills and the faint jagged edge of Mount Ida. The bell rang Slow and Stop down among the Hartlepool engines, and she lay in a jumble of shore-craft off Chanak, sometimes called Sultanieh. A string of low houses and jetties hung over the water with here and there a taller white building under the flag of a Vice-Consulate; rough-tiled roofs and a minaret or two, and at the western end the old white tower and clean-cut earthworks of a fort, where a few elderly muzzles pointed through the embrasures. A great show of mystery and concealment is kept up around these forts, and woe betide the luckless alien who blunders within a stone's throw of their lynx-eyed sentries,

![]()

261

for here this vague measurement is defined and demonstrated with good-sized pebbles by the excited guardians. Even English ladies in their dinghy have been a target for this branch of coast-defence.

Turkish women.

The shores of the Hellespont fairly bristle with fortresses, and the impression forces itself on the simple visitor that in a cross-fire an enemy running down the middle might conceivably suffer less than friends on the opposite bank. There is little likelihood of the precious old relics ever being fired, however, as the coast-gunners are mostly sane men, not given to throwing their lives away in dangerous experiments.

![]()

262

At the time of the mutiny on board the Kniaz Potemkin in the Black Sea, there was much talk of re-armament for the Dardanelles forts, but I should be surprised to find that any such wild scheme has actually been put into effect.

Off Fort Naghara, north-east of the Chanak anchorage, lay three imposing Turkish warships that for many motionless years have maintained a dignified and commanding position, which they will stoutly continue to hold so long as the principal parts of their engines are missing. Years ago, so runs the legend, there was a self-propelling gunboat in the Turkish Navy, which in a moment of spite was ordered to proceed to Malta with a message. Manfully the little crew steamed out on their perilous mission. Days - weeks passed by, but no tidings came of the handful of devoted souls. At last - worn with waiting - the weary watchers witnessed the wished - for wanderers wending their way to welcome wharf. The gallant commander stepped on shore and reported himself.

"Well," said the authorities, "what news?"

The adventurer closed his melancholy eyes."Malta yok!" ["There is no Malta."]

In the Chanak anchorage lay two or three salvage tugs flying the British red ensign. An Englishman there owns a fleet of them, and has all the salvage work of the Levant in the palm of his hand; he wears a white cross on a red funnel. Two German boats with red crosses had lately arrived to drive the Briton from the seas, but when they set out to

![]()

263

pick up a stranded vessel they usually met the white cross towing her in.

More than half the steamers that work through the Straits are British; the balance is made up of Turk, Italian, Austrian and Greek. No vessel may pass the forts from the south-western end after sundown, and the last hours of daylight see one belated tramp after another drop her anchor off the village of Quarantine - just inside the mouth - and swing her high, red-patched sides round with the current. With sunrise and an open door they go threshing through the level water - half the screw out and a mountain of foam under the counter - to the Black Sea ports for their load of grain. Nearly everything goes up in ballast, for foreign goods are not welcomed on that coast.

One night a Russian Volunteer ship went through - the second of these wolves in sheep's clothing. It was nearly full moon, and across the water the European shore showed pale and unreal. Suddenly a hooting broke out, and a cluster of lights came round Fort Naghara. Then a hull, funnel and masts took shape, and the merchant-cruiser ploughed past unchallenged - her decks thronged with troops - to the open seas where she could hoist peace-flag or war-flag, whichever she thought safest.

The old town of Chanak - which means a pot - was first a Genoese settlement. Then came the Greek potters, who gained it a reputation and its present name, and they are still represented by their descendants, but their craft has surely been

![]()

264

lost in the ages. Earthen water-jars and little jugs, of a shape seen all over the Levant, with dabs and zig-zags of colour, are all the modern thumb-workers have to show.

Down the long bazar their hutches crowd into the line of little open-fronted shops under cranky wooden shades. Here are fez-fashioners whose wares sit upon coffee-pot blocks with straight handles; harness makers who conjure amazing results out of wood and string; pasty and cheese sellers; Europe-shops bedangled with crazy-coloured handkerchiefs; lemonade-mongers sitting behind big flagons of canary-coloured hair-wash; fruit-sellers with water-melons piled out on the cobbles, and all the shabby-gaudy colour and heat of the East.

Down the narrow alley under the torn scraps of cord-stretched awning comes a string of gurgling camels following a donkey. A villainous Zibek with short blue breeches and tanned legs leads the jackass. The camels are tied fore and aft with strings from their great pack-saddles, and one or two carry a big, jangling Swiss cow-bell.

Now the camelcade must halt to allow passage for a white, weedy horse and a dwarf Deadwood coach slung high above four small wheels-seats on the floor-level. Sitting cross-legged in this luxurious conveyance are some Turkish ladies going visiting; the native population does all its travelling thus. A "growler" with three wheels and no cushions would be a Pullman car by comparison.

![]()

The Dardanelles.

![]()

265

Straight across from Chanak is the old-world castle of Kilid Bahr, its heart-shaped embattled wall sheltering a square keep by the water's edge. A little north of it is a bunch of Cypress trees where a man may finish his swim if he is keen on emulating Leander. I tackled it on a calm day, going overboard from a shore-boat near the warships. For the first half of the journey a warm current runs northward, towards Constantinople, at about two miles an hour. There were several unaccountable cold patches in the water, and one or two steamers passing within forty or fifty yards churned up some icy waves of it that seemed to come from the very bed of the channel.

After half an hour a head-wind got up, chopping the water into a troublesome jabble and turning it intense blue, and the sandy hill and green bush-clumps looked a long way off. About half-way over the current runs in the opposite direction - towards the mouth of the Straits - rather faster than the first stream, and the landing-point on the opposite shore, which had been drifting gradually away, was brought rapidly back into line. Old Osman in the boat behind waved the direction - a useful guide when one is swimming on the back. One or two Mytos caiques were heading across, heeling over to the press of their leg-o'-mutton sails. A Navy boat passed, and the men in her shouted and wanted to interfere, but the old waterman soothed them and they splashed off out of sight.

Three hundred yards from the European shore

![]()

266

the current suddenly ran like a mill-race, but the active bit was soon crossed and a landing made below the Cypress trees-an hour and seven minutes from the start. The strait at that point is a mile wide, and counting the drifts on the currents one travels about three miles.

The Turks in this part of Asia Minor are law-abiding and live on good terms with the Christians - a striking contrast to the state of affairs over the water. The troops are kept well in hand by the General commanding the coast defences, Maghar Pasha; and the Governor, Hifzi Pasha, is that rara avis of the East - an honest man. Backed by the Commandant of Gendarmerie, a man of energy and an iron hand, he keeps the Sanjak [Province.] quiet, and has cleared it of bad characters to such a tune that the traders - Greeks, Jews and Armenians can now carry goods and specie unescorted in the interior without fear of robbery.

I think I have hinted before that the Turkish soldier's pay is of the nature of an elusive vision which seldom materialises - a will-o'-the-wisp which he sees ever flitting in the distance, luring him on. On a few rare occasions the pleasures of anticipation have been known to pall upon him and he has clamoured in a body for solid cash.

Once upon a time the Dardanelles troops, in spite of their superior discipline, became so noisy that the General (not the worthy officer aforementioned) pulled himself together and looked about for something to throw down to them. It

![]()

267

happened just then that there had been a more than usually pressing call for funds for his Sultanic Majesty's coffers at Constantinople, and the Commandant of Gendarmerie had opened a subscription-list for the peasantry, Moslems as well as Christians, to which they contributed in their usual open-handed manner. It is surprising how generous one can be when the alternative is indefinite gaol.

The proceeds of this levy were sent to the coast for shipment to Constantinople, but the needy General, whose motto had ever been "Charity begins at home," fell upon the convoy and fed his obstreperous children on it. So the rustic shareholders were told there had been a slight mistake and would they mind paying up the second call?

There was no news of the Malacca, and no event calculated to shake Europe to its foundations seemed likely to happen in the Dardanelles for a day or two, so, from the hospitable "Maison Calvert" at Chanak, I set out for Troy Plain and "Thymbra," where a son of the house farmed his own thousand acres.

On the strength of painful memories concerning pack-saddles I had this time conveyed my own old bit of pigskin from Salonica in a sack, which handy envelope now lay between "Parker's pride" and the back of a lean white pony. In this blissful land you can choose whether you will take a mounted gendarme or not. Think of it! Like asking whether you prefer hunting or hanging.

![]()

268

A good road touches the little Greek coast villages, and up on the divide where it was worn out they were banking and laying a new one. White bullocks stood stolidly in the shade, taillashing at the flies. Magpies by dozens flapped over the Agnus Castus bushes, and weasels scurried under the scrub. White-shrouded heads of soft-eyed women peered over the low wheat stacks, and the steady wind spread the glinting dust in even clouds. Clean smell of straw and fierce, ripening sun.

By a roadside spring a big valonea oak threw a shadow circle on the grass:

"Here, with a loaf of bread beneath the bough,The pony chewed the crust and a piece of cucumber, having learned in an abstemious career to eat what he could get whenever he could get it.

. . . . . . And wilderness is Paradise enow."

Hissarlik, as the natives call the site of Troy, is not particularly easy to find, and the narrow trail has many off-shoots. At the end of six hours' riding a few scattered blocks of marble gleam in the thick brushwood, and you are among the ruins. Without knowledge of the subject and without a guide the pits and intersecting wall-layers - the piled stones and half-hid bricks of the excavations are unintelligible. Dr. Schliemann discovered seven cities, one on top of another, but even with a list of them and what you might call their ingredients I could make very little of it. Scrambling among the stones at the bottom of one of the pits, nosing

![]()

269

the sheer wall-section, I thought I had lit on city number three, which the list said was made of shells and fishbones, when a dark figure with knives and yataghans protruding from it loomed on the edge of the excavation and signalled "come out of that." On rising to the surface I was given to understand that casual wanderers were not supposed to paw the buried cities, and another portentous discovery was lost to the world.

Jogging over the hump and dip of the Troad, I pointed for a dark line of poplars lifting now and again in the distance. A cattle-drover with a red-swathed head and an old six-foot firelock on his back holloaed a husky dog round the flank of his herd. A string of supercilious camels padded past, and a solitary stork flopped solemnly over the big poplars. Out on the far side of them a long stretch of stubble carried away to clustered oaks and a little hill capped with white walls in the green. Thymbra the ideal!

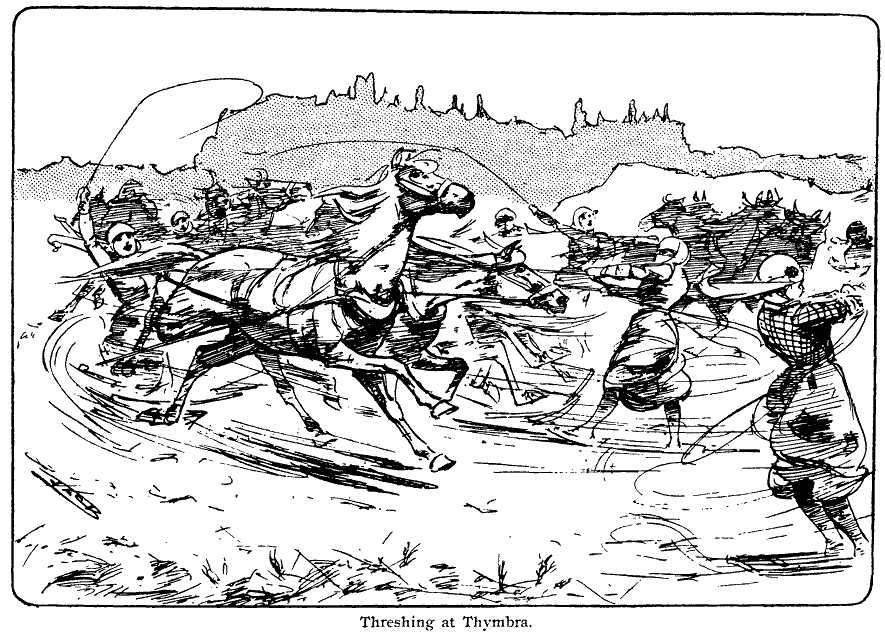

At the hill-foot they were threshing wheat.

Picture the contents of a thousand straw-mattresses strewn over an open-air circus ring, and half-a-dozen pairs of horses racing round and round on the crushed straw drawing flying figures after them - by the reins, apparently; a setting of oaks and poplars, a blazing sun and a roaring wind swishing the chaff in your eyes - and you have the first impression of a threshing-floor.

Going closer you see that each pair of little clean-legged horses is pulling a flat board, turned up a little at the fore-end. On this stands a Greek

![]()

270

girl, her head swathed in a white yashmak with a long end flying behind her in the wind, for she is as careful of her complexion as any Parisienne. She is clad in a blouse and voluminous shalvas, caught in below the knee and showing her sturdy legs in woollen stockings - feet planted firmly apart to keep her balance on her flying sleigh. The under part of this board is set with rows of sharp flints that chop the straw and dash the corn out of the ear. Since the days of Abraham this threshing-board has not been altered; so with the other farm-implements.

Round and round fly the teams, now steadying to a trot, now breaking into a headlong gallop to the wild cries of the merry little drivers. And these know something of driving. Two teams coming one way meet two coming the other way, spread, and let them through with six inches to spare between each of the four. To do this neatly at full gallop needs an eye and a hand.

Beside the threshing-floor is a piled bank of threshed-out corn and chaff in which wade the winnowers - bare-legged men - tossing the stuff with toothed wooden shovels. A quick turn of the wrist drops the grain to one side and the chaff flies downwind with a shimmer of gold; the "winnowing-wind" they call it, and it blows all the summer out of the north.

By the path up to the homestead rise the gaunt limbs of an American windmill-pump, the steady "clank-clank" of the rod answering the breeze. There is an assurance about that metallic voice on its iron

![]()

271

Threshing at Thymbra.

![]()

272

legs, untroubled by its Old Testament setting. A calm assertion of knowledge and power and the relentless March of Machinery as it observes through its nose "Crank-Tank-Yank."

And this hill is Homer's Thymbra - "Thymbra's ancient wall" - where Apollo had a temple, and where the Phrygian horse were encamped. Today that wall is underground and on its site stand orderly farm buildings and a little white house with a shady verandah. The friendly Englishman, in tweeds and stockings, walked me round to the trellissed belvedere above the garden where his wife, a charming fair-haired Greek lady, was pouring out tea. The Hope of the House, a hearty young Saxon of six, laughed under a big sailor hat, between the brim and crown of which strained relations existed, and his pretty dark-haired sister brought a big green bowl filled with glorious firm butter, kept cool at the bottom of a dry well.

As we talked a long humming note came up from the plain below. It grew to a chord, for all the world like half-a-dozen finger-bowls with wet fingers circling their edges. Now and then there was a deep key-note like a 'cello, and a chirping like a piccolo. The chords changed, slid into minors and out again - always harmonious - growing in volume. What was this Thymbrian orchestra?

On the white, blue-shadowed road to the threshing floor hung a little cloud of dust, gold in the sunset. Bullock carts! The AEolian music was no more than the crying of the ungreased wheels on their wooden axles as the Guernsey-coloured

![]()

273

bullocks drew their little grain-laden carts to the granary. But if one of those gentlemen who compose "tone poems" wants to write a pastorale there is a theme for him.

The spell of that idyllic place was a strong one. The life and vigour of the threshing teams and the hardy children of the ancient Trojans - strong men and buxom women - who worked them; clean wind across long, waving acres of black-bearded wheat; the hum of bees under the valoneas, seeking the honey-dew among their leaves; the colours of the sloping garden and its wealth of fruit-plums, quinces, cherries, apricots and almonds, grapes in wide-stretching vineyards and great strawberries of celestial flavour. The deep verandah in cool moonlight, and the big moths darting through the creepers; or the bivouac under the pines at dawn, when the corn-guard woke to catch the hobbled horses.

There with the "happy family" - kindliest folk - I spent some blissful days in thrall of that good life. In the wide choice this patchwork world has to offer, it would be hard to beat.

* * * *

Off the mouth of the Dardanelles H.M.S. Lancaster cruised, waiting for developments. On the cliffs, over the heat-shimmer of the burning sand, sat the news-hunter, staring through field-glasses beyond Tenedos and the golden islands reflected in the sea. Two days later the "Malacca Incident" had passed.

![]()

274

As the sun went down like a big red beehive over the end of Imbros, a tiny Turkish steamer, with the old kit-bag and the saddle in its sack, waddled out past Sedil Bahr and pointed away on the Home Trail.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]