PART ONE. Thracians and Greeks

III. Odessos 49

3 THE THRACIAN INTERIOR BEFORE THE MACEDONIAN CONQUEST

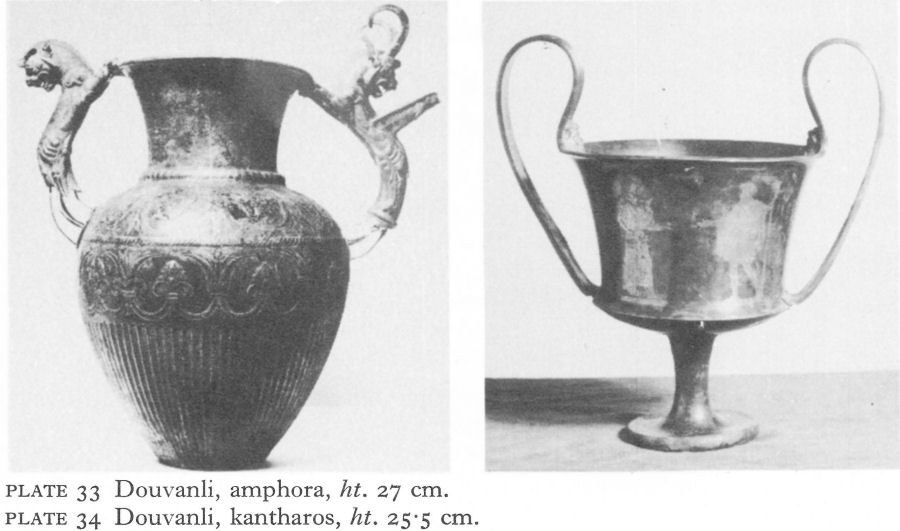

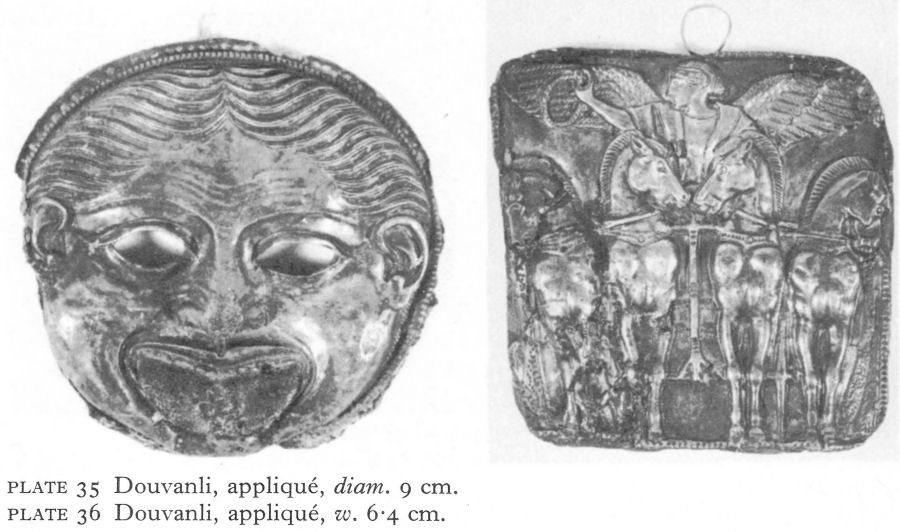

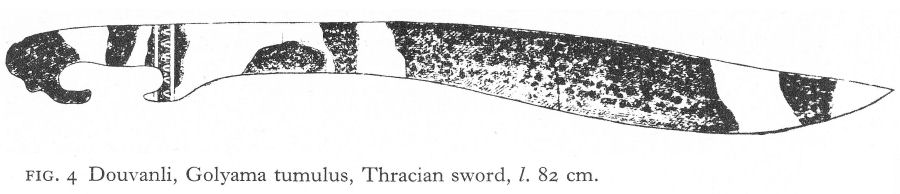

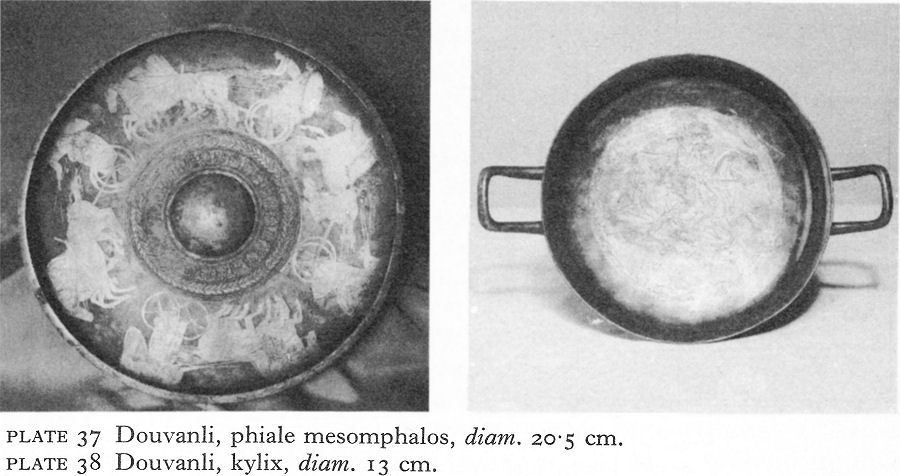

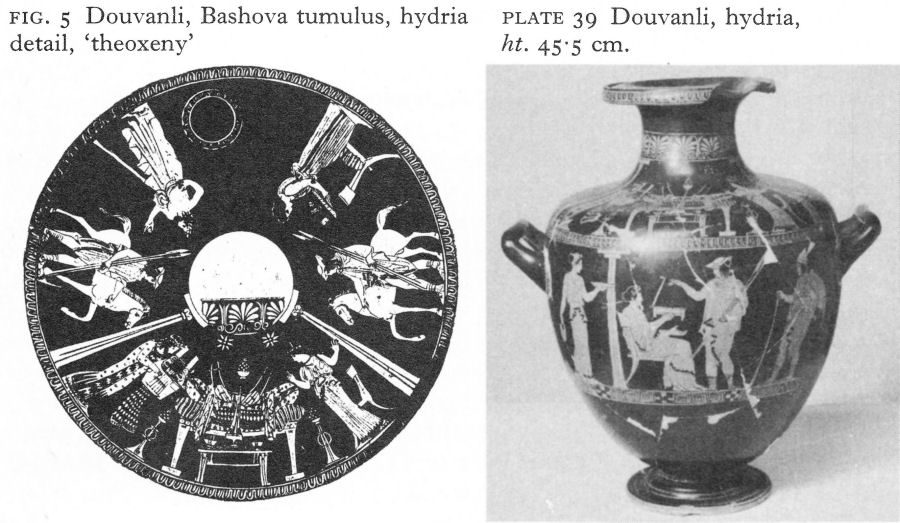

II. Douvanli 58

(The Moushovitsa tumulus; The Koukouva tumulus; The Lozarska tumulus; The Golyama tumulus; The Arabadjiska tumulus; The Bashova tumulus)

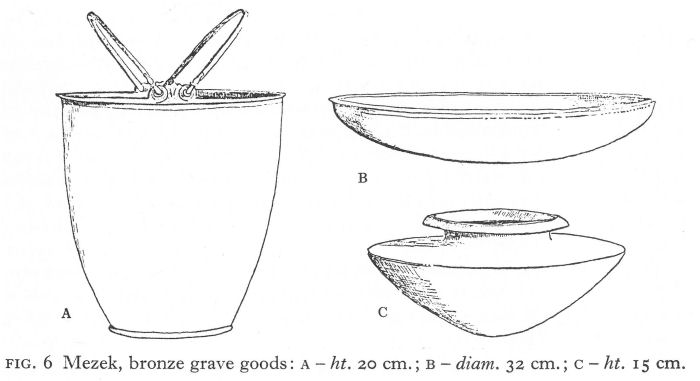

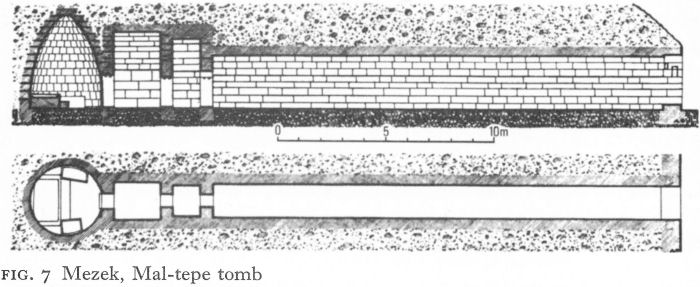

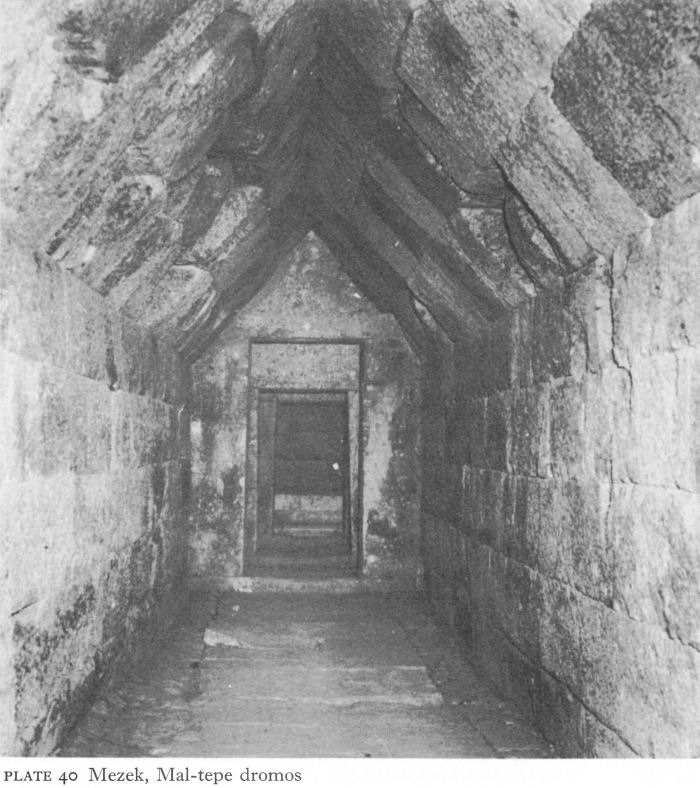

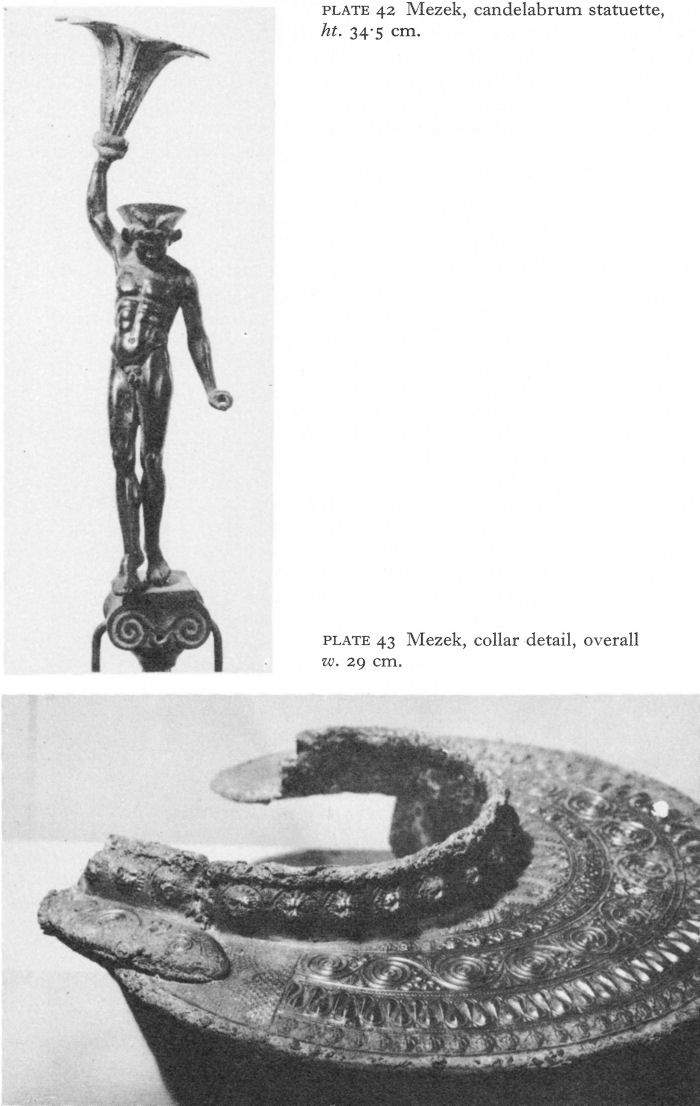

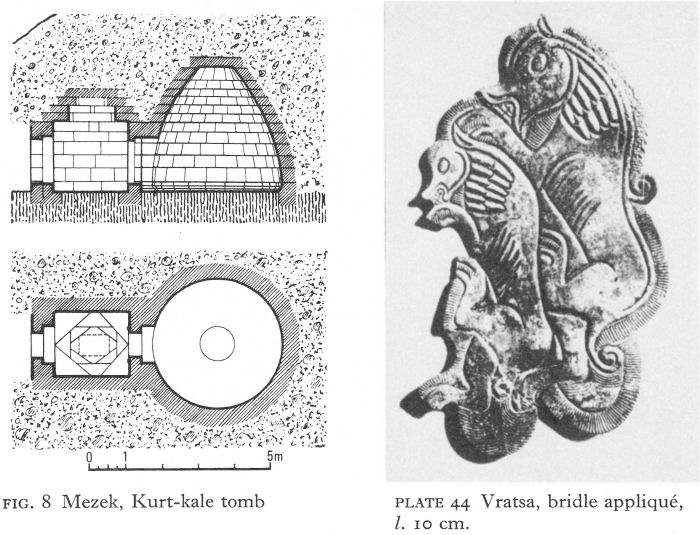

III. Mezek 69

(Mal-tepe (Imanyarska tumulus); Other Mezek tumuli)

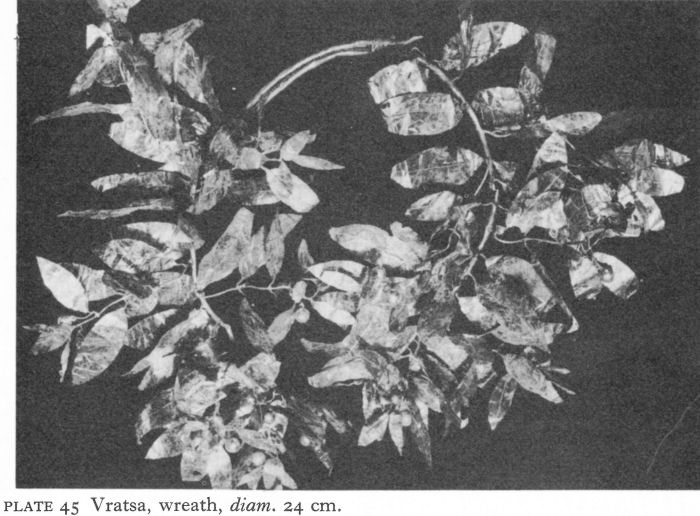

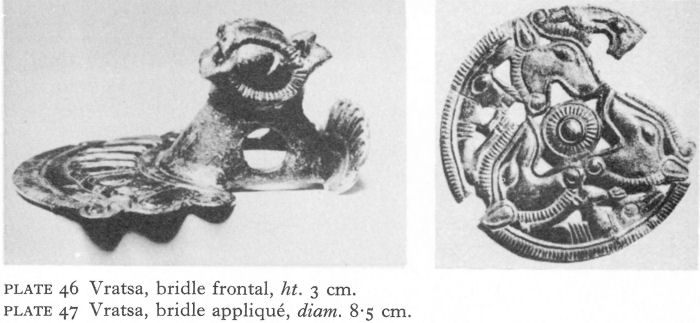

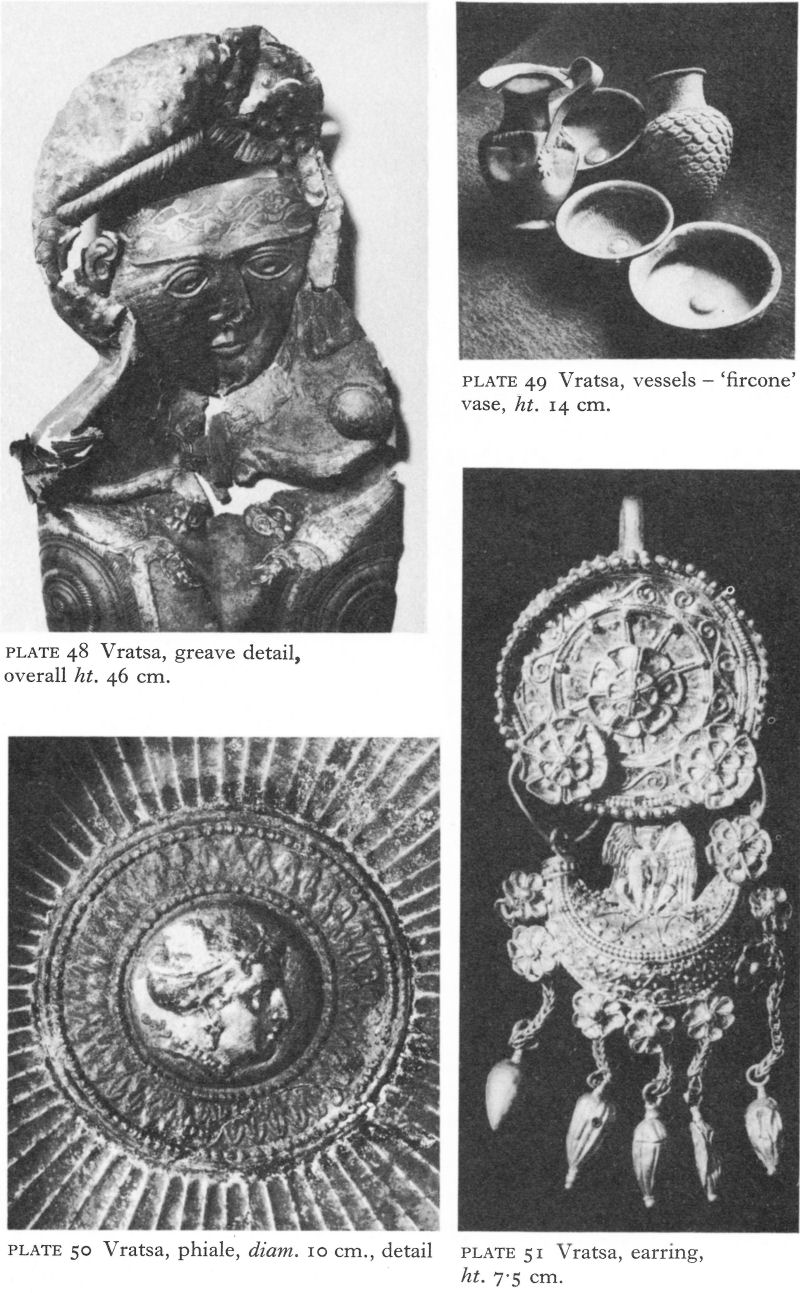

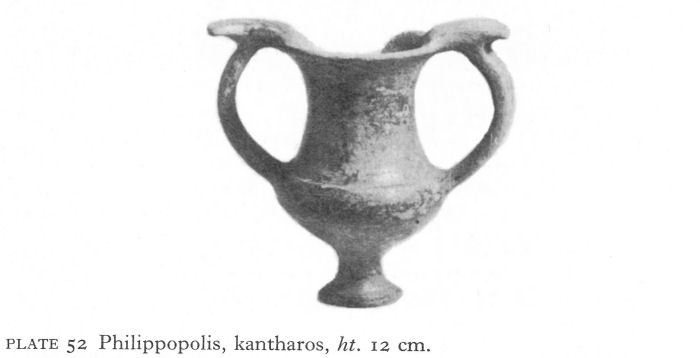

IV. Vratsa 76

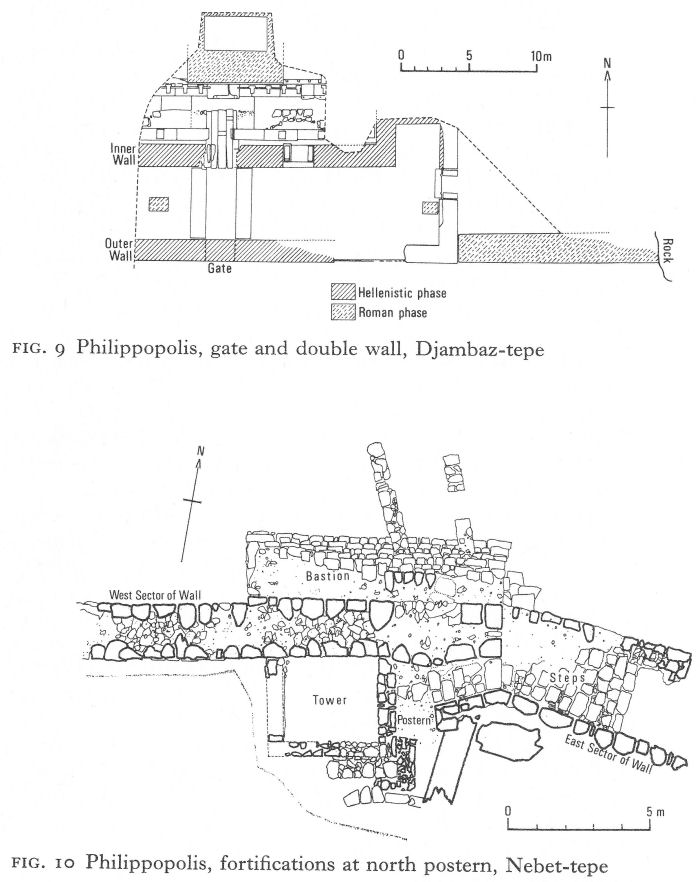

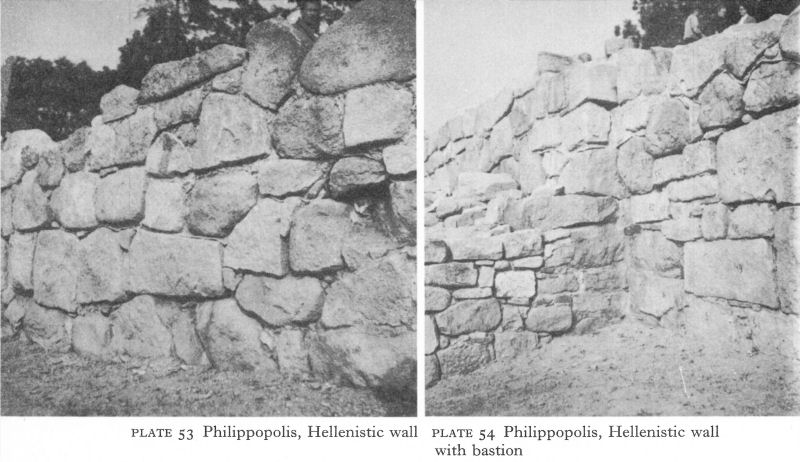

4 MACEDONIAN AND HELLENISTIC INFLUENCES

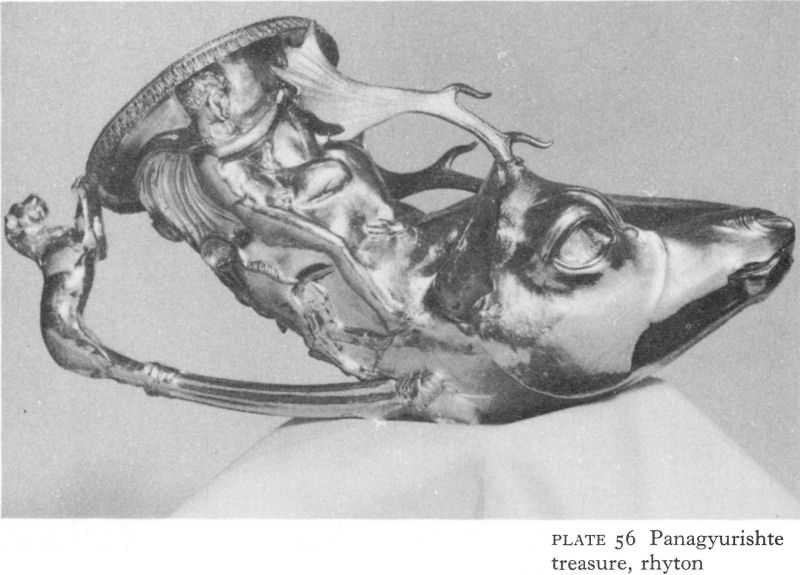

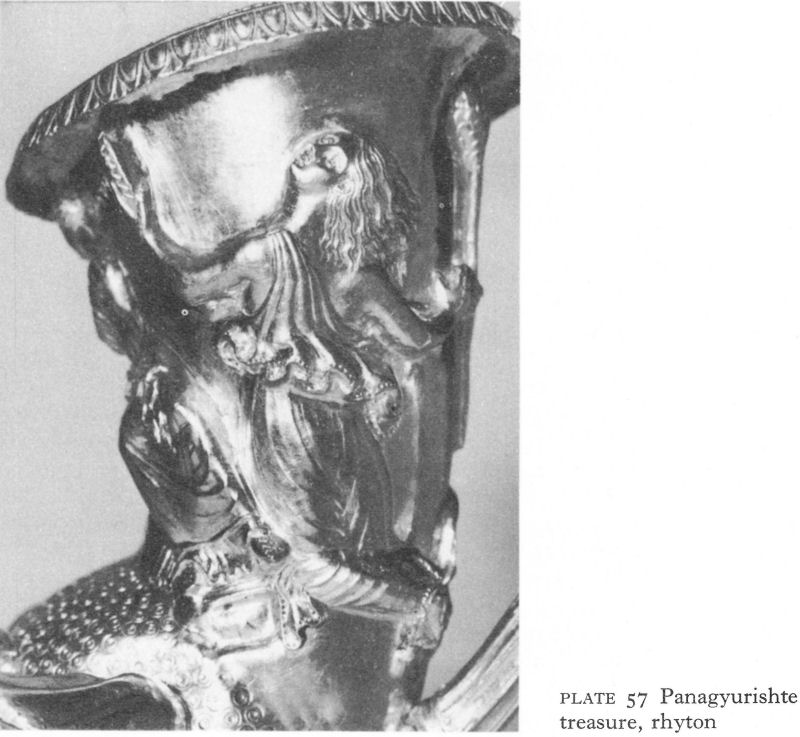

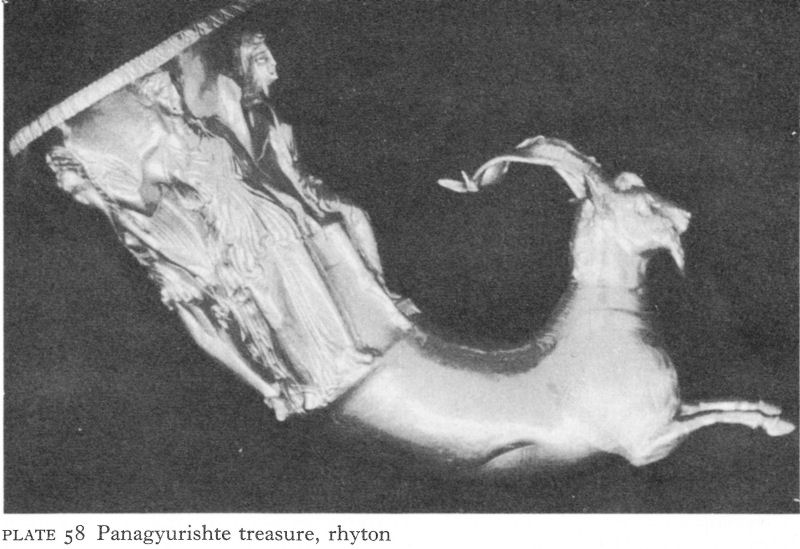

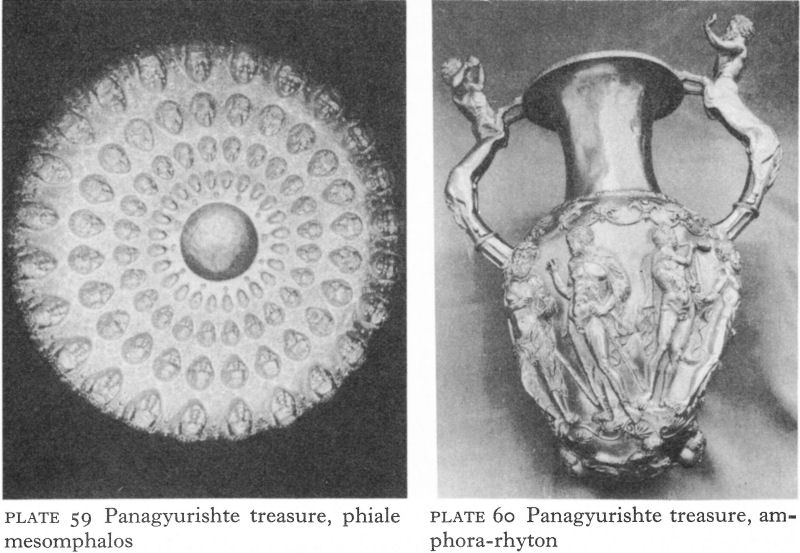

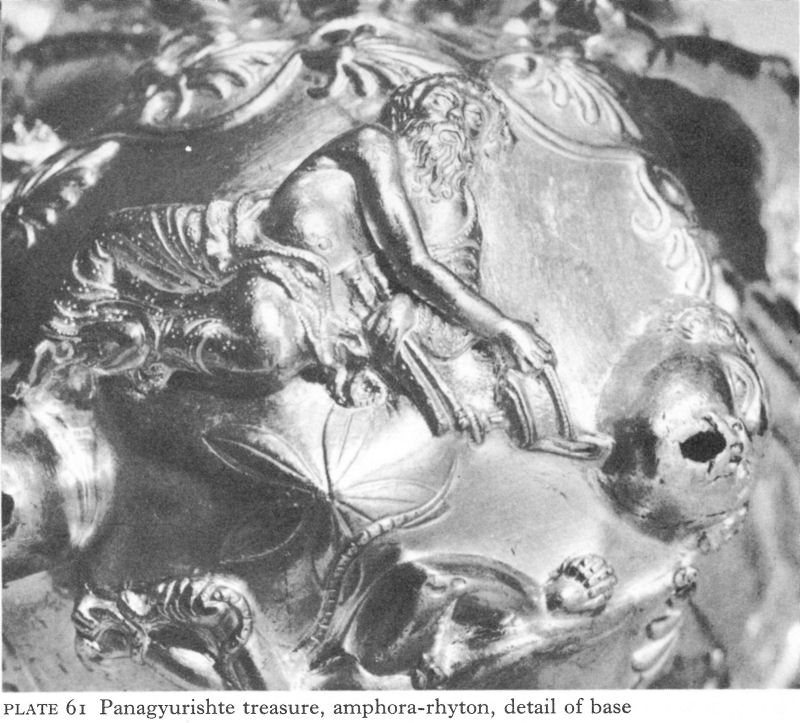

II. The Panagyurishte treasure 85

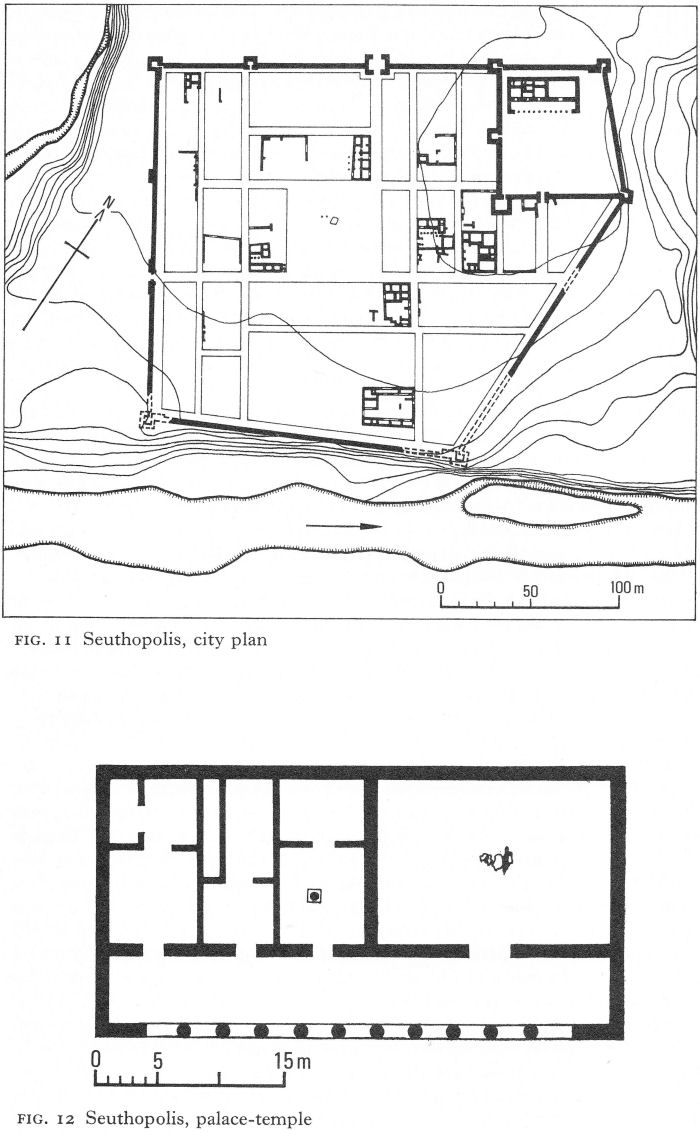

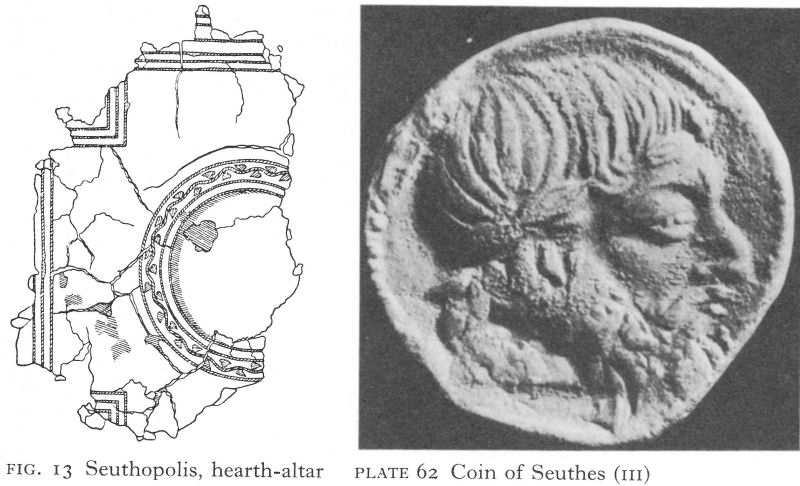

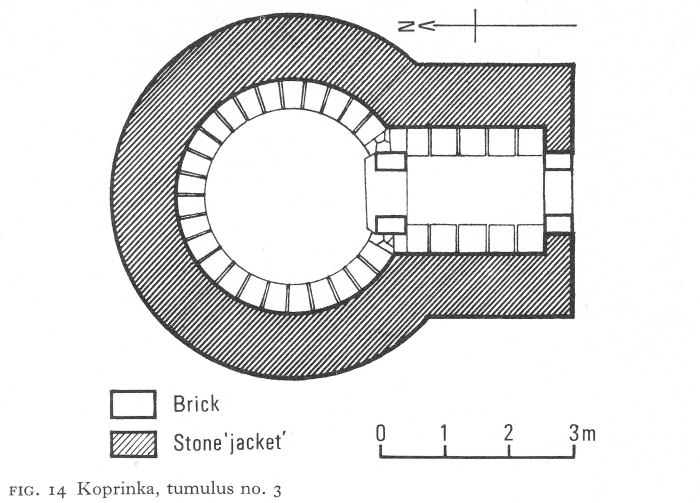

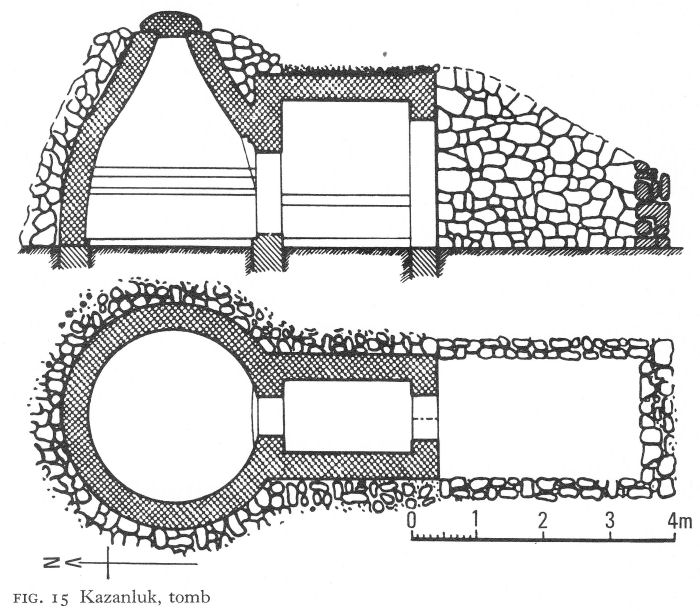

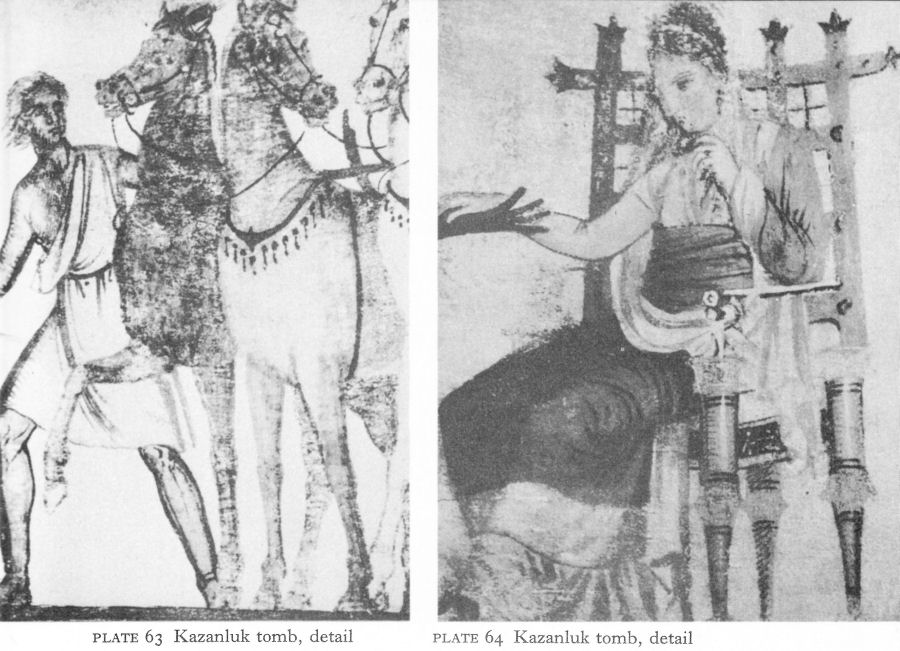

V. Tumuli of Seuthopolis and the Kazanluk region 97

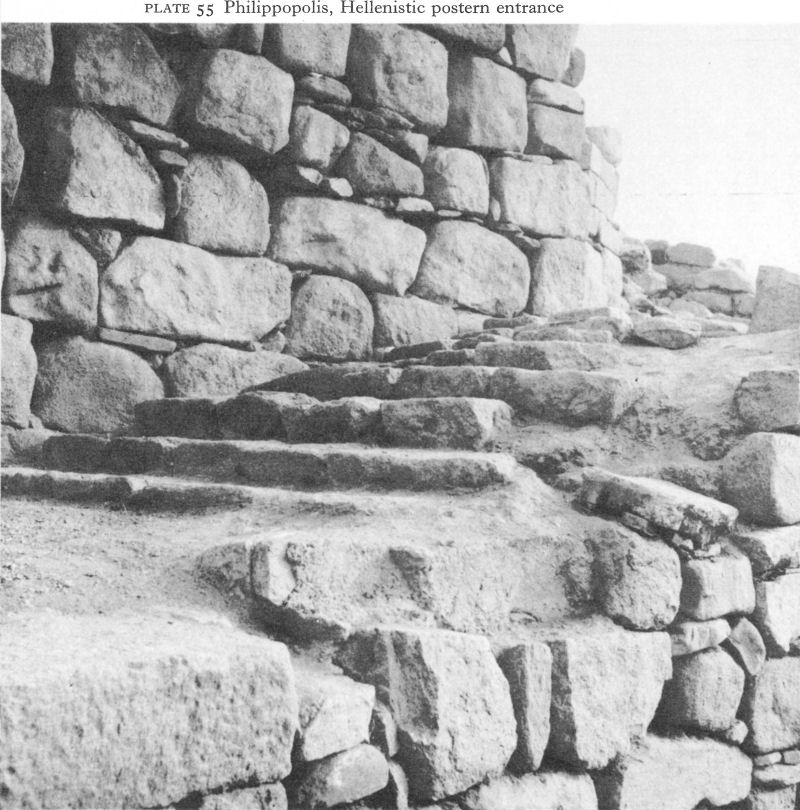

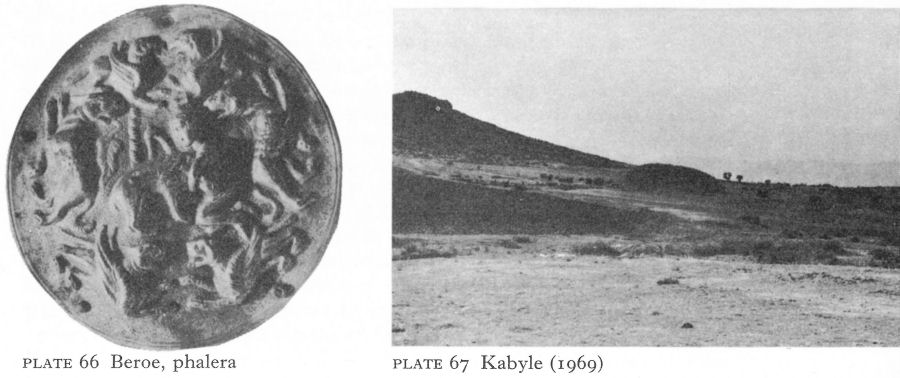

VI. Kabyle 103

VII. Beroe and its vicinity 104

VIII. Chertigrad 105

1 The Land and the People

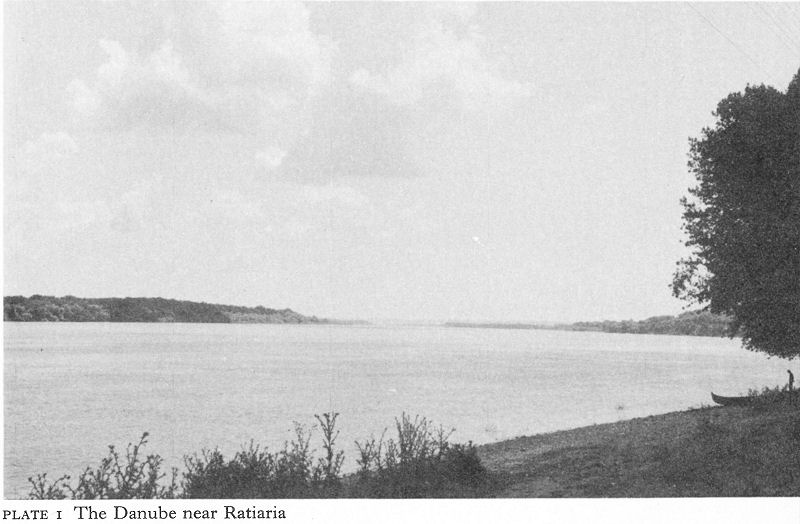

The land of Bulgaria, less than half the size of Great Britain, emerges into history as the core of a much bigger area of south-east Europe inhabited by the Thracian people. To east and west - the shores of the Black Sea and the mountainous backbone of the Balkan peninsula - the boundaries of modern Bulgaria coincide with those of ancient Thrace. To the south and south-east, a large area of Thrace bordering the Aegean, the south-east shore of the Black Sea, and the Sea of Marmara falls within modern Greece and Turkey. To the north, except for a short land frontier across the Dobroudja, Bulgaria’s frontier with Romania is the Danube (Pl. 1). In early Antiquity the Danube, then known as the Istros or Ister, served as a unifying link between the Thracians living to the south and those whose territories reached into the Carpathians and the north-west hinterland of the Black Sea.

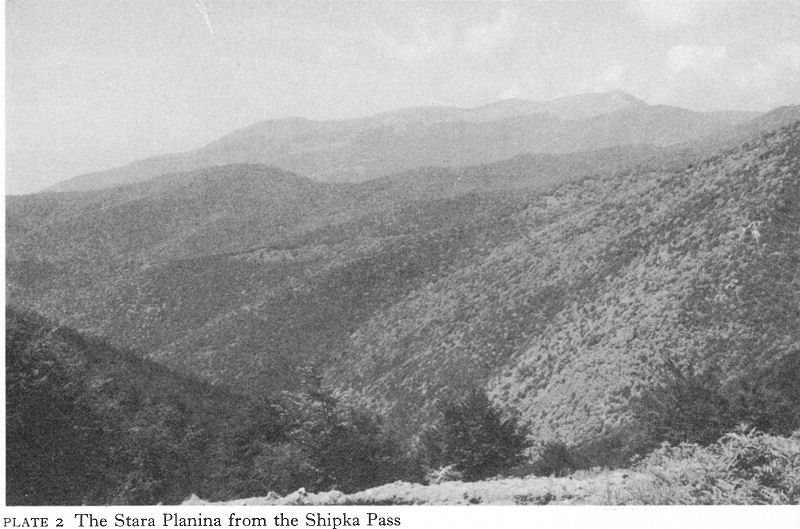

Within Bulgarian Thrace the dominating feature is the west-east mountain range known to the Greeks as the Haimos, today sometimes as the Balkan, but in Bulgaria usually called the Stara Planina, 'the Old Mountain’. Penetrated by only one river, the Iskur, the ancient Oescus, in the west, most of its passes, except in the extreme east, must have been closed during the harsher winters that then prevailed. Rising steeply from the south and descending gradually towards the Danube, tributaries of which cut steep gorges through its extensive karstic foothills, this range and not the Danube was the original dividing-line between north and south Thrace (Pl. 2).

South of the Stara Planina and protected by it from the northern winds lies the fertile Thracian plain, sometimes now called ‘the market garden of Europe’. At the end of the eleventh century, according to the Gesta Francorum, Bohemond and his crusaders found here ‘an exceeding abundance of corn and wine and nourishment for the body’. In prehistory this was one of Europe’s cradles of civilisation. The Thracian plain is watered by the river Maritsa, the ancient Hebros, which empties into the Aegean. Its numerous tributaries include the Tundja, the Greek Tonzos, the upper course of which drains the Valley of Roses lying between the Stara Planina and a lower, shorter range, the Sredna Gora.

The Thracian plain is bounded on the south by another west-east belt of mountains, penetrated by the Struma, the Greek Strymon, in the extreme west, partly by the neighbouring valley of the Mesta, the Greek Nestos, and decisively in the east by the Maritsa and Tundja. Between the Struma and the Maritsa stand the deep and intricately folded massif of dense forests, high fertile valleys, plateaux, and peaks formed by the Rila, Pirin, and Rhodope ranges. In the east the Rhodopes are lower, as are the Sakar and Strandja hills which extend to the shores of the Black Sea, but they were wide and high enough to hinder communication except where the rivers opened gaps.

The central region of west Bulgaria, in effect an abutment of the spinal massif of the Balkan peninsula, comprises a series of relatively high, fertile, and wellwatered mountain-ringed plains which can be termed collectively the Western uplands. The largest contains the modern capital of Bulgaria, Sofia, and has

24

![]()

![]()

25

Plate 1 The Danube near Ratiaria

Plate 2 The Stara Planina from the Shipka Pass

![]()

26

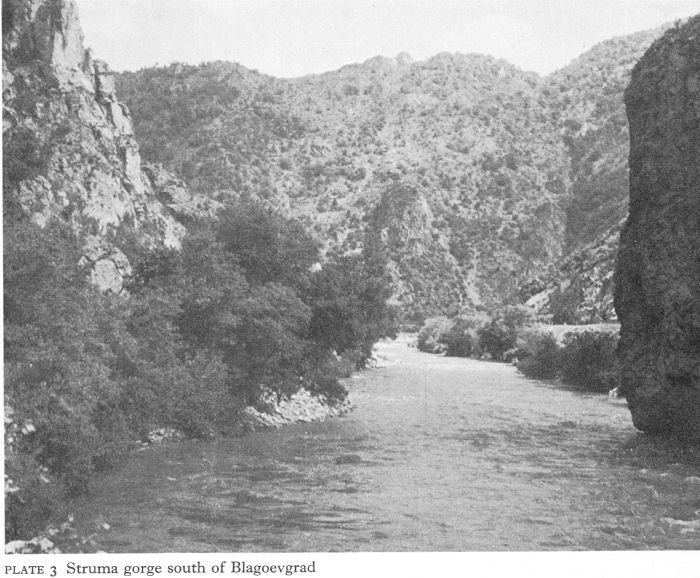

always been an important centre of communications. The Struma valley, in places no more than a narrow gorge (Pl. 3), provides a route to the Aegean and others off it lead to northern Macedonia and to the Adriatic. To the north the Iskur links the Sofia upland with the Danube valley.

The Sofia upland is also crossed by the great highway which passes from Central Europe via Belgrade and Niš and on through the Thracian plain and the Maritsa gap to the Bosphorus and Asia. Often referred to as the ‘Diagonal’, it has had at least seven thousand years use.

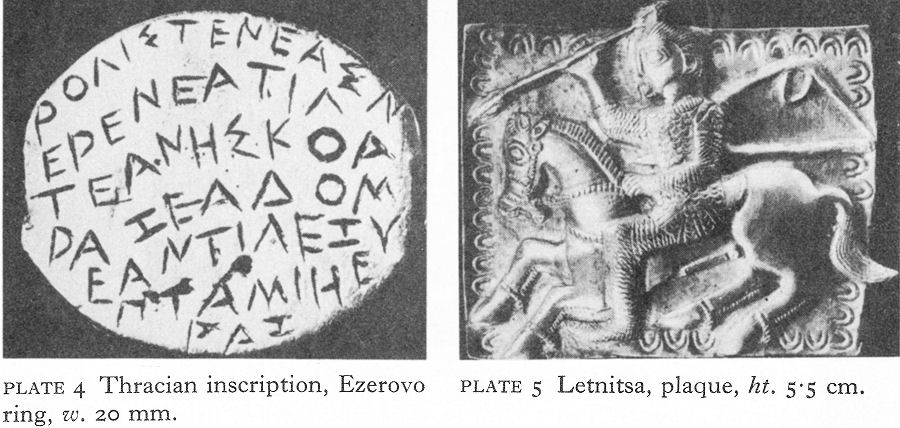

The Thracians are identified as speaking a common Indo-European language with certain regional variations of dialect. They can also be distinguished from their neighbours by customs reflected in archaeological finds made in excavation of their settlements and burials. Such knowledge of the Thracian language as exists is mostly based on place and personal names and rare, brief inscriptions using Greek characters, for there was no written Thracian language (Pl. 4). Hence the historical sources are Greek or Roman, written with varying degrees of prejudice and accuracy from Greek or Roman viewpoints and consequently needing to be treated with appropriate reserve.

A difference can be observed between the Greek attitude towards the Thracians and their eastern neighbours, the Scythians. The Greeks preferred the latter. They lived far enough away for neither party to appear a danger to the other, and the agricultural riches of the Ukraine infinitely surpassed the resources of the much smaller Thracian plain. The profits of the Scythian trade are not only shown in the size and prosperity of the neighbouring Greek colonies, but also by the immense scale, in terms of wealth and ritual slaughter, of the Scythian royal graves.

The Thracians were not only a much less attractive commercial proposition; they were unruly, unreliable, and pugnacious, and Thraco-Greek antagonism dated at least as far back as the Mycenaean period: in the Iliad they appear as firm allies of the Trojans against the Greeks.

Excavations in Bulgaria have invariably shown a Thracian substratum beneath the Greek coastal cities. According to Strabo, the Black Sea colony of Mesambria (Nesebur) was the ‘bria’ - a Thracian word for town - of a chief named Mena. It is unlikely, certainly in the case of the earlier settlements, that the Thracians yielded their homes to the Greeks without bitter fighting. Homer’s description of an incident in the Trojan war could easily have been a piece of sixth- or fifth-century b.c. reporting. A Thracian captain Peiros, having first smashed the ankle of Greek Diores with a jagged stone, had despatched him with his spear. Whereupon

Aetolian Thoas hit him in the chest with a spear, below the nipple, and the bronze point sank into the lung. Thoas came up to him, pulled the heavy weapon from his breast, and, drawing his sharp sword, struck him full in the belly. He took Peiros’ life but did not get his armour. For Peiros’ men, the Thracians with the topknots on their heads (Pl. 5), surrounded him. They held their long spears steady in their hands and fended Thoas off, big, strong and formidable though he was. Thoas was shaken and withdrew. [1]

While prepared to view barbarians with disdain but equanimity from a distance,

![]()

27

the Greeks usually regarded the Thracians in the light of undesirable neighbours, as indeed they often were.

Herodotos, describing the Thracians as the most numerous of peoples after the Indians, comments on the chronic disunity which effectively prevented them from becoming the most powerful of nations. Indications of the main tribal groupings by Greek historians and geographers are understandably more vague about the lesser-known interior than the Aegean coast. Tribal territories, while based in general on geographical features, were probably subject to considerable variation. Smaller tribes or clans tended to attach themselves to larger groups, according to the prevailing situation.

South of the Stara Planina, based on the Tundja and lower Maritsa and extending over much of the Thracian plain and eastern Rhodopes were the Odrysai. Occupying the western end of the Thracian plain but chiefly based on the western and central Rhodopes were the fiercely independent Bessi. The Maidi controlled the middle Struma and the Dentheletai its sources;

Plate 3 Struma gorge south of Blagoevgrad

![]()

28

the Serdi of the Sofia upland may have been a branch of the latter, but parts of the Western uplands were also inhabited by the Celtic Skordiski. North of the Stara Planina, the Triballi lived west of the Iskur-Vit (ancient Utus) divide, to the east of which were the Getai, the name given to a large group occupying both sides of the Danube. Herodotos calls them the most valiant and just of the Thracians, possibly a reflection of the better relations between the north-west Black Sea colonies and the local tribes than those enjoyed by most southern Greek settlements ; but the context suggests that the tribute may have been due to the Getai having been the first Thracians to oppose Darius during his preparations for the invasion of Greece.

Xenophon gives a characteristically vivid impression of the Thracian settlements he encountered during his service with Seuthes in what is now Turkish Thrace, [2] but archaeology is only now beginning to fill in the details of the picture and show if what he saw was typical. To take one example, a preliminary survey of Getic villages in north-east Bulgaria [3] suggests a general pattern of closely grouped small rectangular huts, half dug into the ground, constructed of clay on a wooden framework and roofed with thatch. Each hut had a yard with pits for rubbish and grain storage, enclosed by a wall or fence. Clearly marked postholes for the last match Xenophon’s description of Thyni villages in southeastern Thrace, where the houses were enclosed with high fences to protect the livestock.

Nothing which could be called a city (polis) has been identified in the interior before the Macedonian conquest of Philip II, although some larger settlements may have had an urban character in that they were markets or craft centres. Dry-stone-walled fortresses, making full use of natural advantages, were situated on low hills in commanding positions in or on the edges of the Thracian plain to serve as a refuge for neighbouring villages. In the more remote and less peaceful mountain areas, villages were often fortified. Most of the former have undergone an extent of destruction and rebuilding which has largely obliterated surface evidence of Thracian occupation. The inaccessibility of the latter, particularly in the Stara Planina and the Rhodopes, has afforded more protection, not least from the developer and those seeking an easy source of building material. Understandably, excavation has had a lower priority here than urgent salvage digs. Although some work has been carried out, for example at Chertigrad in the Stara Planina (p. 106) and at Boba on the Shoumen plateau, [4] and many other sites have been identified by surface finds in all mountainous areas, little is yet known about Thracian settlements in the sixth to fourth centuries.

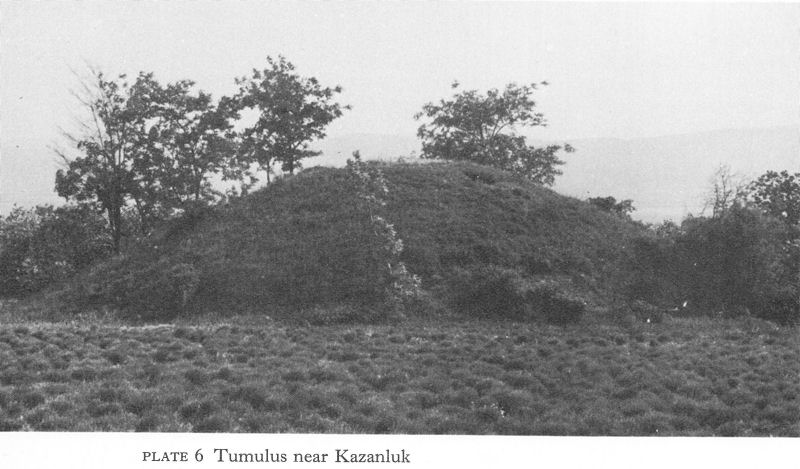

More information comes from the tumuli or burial mounds dotted throughout the countryside - in 1942 estimated to number about fifteen thousand, although many had disappeared under the plough or through erosion - still eloquent witnesses of the funerary rituals associated with Thracian belief in life after death (Pl. 6). The earliest tumulus burials belong to the Bronze Age and there was a degree of continuity during the period known as ‘Early Iron’ or ‘Hallstatt’. New wealth acquired by the Thracian chiefs from the Greek trade gave a fresh impetus to this form of burial, as it did to an even greater degree among the Scythians. The conspicuous nature of the tumuli has made them obvious targets for robbers and although the problem of pin-pointing a burial in a mound perhaps 50 metres in diameter and 15 metres or more high has sometimes

![]()

29

defeated such attempts, the fact that wealthy Thracians were buried with rich items from the treasure they owned when alive - rather than with inferior substitutes as was often the custom in Greek graves - has been a constant spur to the fortune-hunter. But happily some have escaped.

Plate 4 Thracian inscription, Ezerovo ring, w. 20 mm.

Plate 5 Letnitsa, plaque, ht. 5.5 cm.

Tumulus burial was common to all the Thracian tribes, but the construction of the tomb and of the mound varied considerably, as did the funerary ritual. Tumuli were built singly or in groups and closely or widely spaced. A large necropolis could cover a huge area. Dimensions varied; the present height may be no guide to the original and, although less subject to change, the diameter at the base varied enormously. Some tumuli were enclosed by a low retaining wall. The mound might consist of earth, sometimes mixed with rubble or pebbles, or a dry-stone cairn might enclose the tomb and the rest of the mound be of earth.

A large tumulus might contain several burials, sometimes occurring within a fairly short time of one another. The grave itself might be a pit, perhaps roofed or lined with branches or beams, or a stone construction of varying complexity, consisting of one or more compartments. In more elaborate stone tombs a tendency towards a north-south orientation has been observed, the entrance being to the south; houses were probably built in the same way. Cremation and inhumation were practised in the same necropolis and even in the same tomb: if grave goods rightly interpret the sex of the deceased, this was not a factor in the choice. The act of cremation was carried out either at the grave or outside the mound. Herodotos gives what may be an eyewitness report of a burial on the outskirts of a Greek colony:

The funerals of the wealthy among them are celebrated in this manner. They expose the corpse during three days; and having slain all kinds of victims, they feast, having first made lamentation. Then they bury them, having first burnt them, or at all events placing them underground; then having thrown up a mound, they celebrate all kinds of games, in which the greatest rewards are adjudged to single combat, according to the estimation in which they are held. Such are the funeral rites of the Thracians. [5]

![]()

30

Referring to the ritual of Thracian tribes in the west, Herodotos writes:

Those above the Crestonaeans do as follows: each man has several wives; when therefore any of them dies, a great contest arises among the wives, and violent disputes among their friends, on this point, which of them was most loved by the husband. She who is adjudged to have been so, and is so honoured, having been extolled both by men and women, is slain on the tomb by her own nearest relative, and when slain is buried with her husband; the others deem this a great misfortune, for this is the utmost disgrace to them. [6]

The picture presented by the Greeks of Thracian religion is confused. Herodotos describes the Getai as worshipping a single god and as believing in their own immortality. The Getic god was known by several names, one being Zalmoxis, and Herodotos recounts a Getic custom:

Every fifth year they despatch one of themselves, taken by lot, to Zalmoxis with orders to let him know on each occasion what they want. Their mode of sending him is this. Some of them who are appointed hold three javelins; whilst others, having taken up the man who is to be sent to Zalmoxis by the hands and feet, swing him round, and throw him into the air, upon the points. If he should die, being transfixed, they think the god is propitious to them; if he should not die, they blame the messenger himself, saying, that he is a bad man; and having blamed him, they despatch another, and they give him his instructions while he is yet alive. [7]

On the other hand, Herodotos refers to Thracian gods of tribes south of the Stara Planina by the names of members of the Olympic pantheon.

Plate 6 Tumulus near Kazanluk

![]()

31

Plate 7 Thracian Horseman relief, ht. 20 cm.

Except for their kings, who, he says, worship Hermes as their supreme and ancestral deity, only Ares, Dionysos, and Artemis are acknowledged. Unlike his remarks about the Getai, it may be suspected that this information was second-hand, for these are manifestly Hellenised versions of Thracian deities. Hermes was the son of Zeus and guide of the dead, but perhaps also reflected the taxes extorted by the Thracian kings from the Greeks, as Ares the fighting qualities of the Thracians, ‘for whom to be idle is most honourable but to be a tiller of the soil most dishonourable; to live by war and rapine is most glorious’. [8] The extent to which the Greeks adopted and perhaps adapted the Thracian attributes and rites of Dionysos is unknown,

![]()

32

but in Thrace it is probable that he was essentially a fertility god. Artemis had many aspects; Bendis was, as far as is known, the only Thracian goddess; as such, hunting was one of her attributes and in this respect, but not necessarily in others, they corresponded.

The Thracians borrowed their religious representational art as well as their alphabet from the Greeks. Thus Thracian religion was further disguised by a fundamentally Greek iconography. It was not, as far as we yet know, the Thracians but the Greeks of Odessos (Varna) who built a temple to the Getic ‘Great God’ and certainly the Greeks who depicted him on their coins. ArtemisBendis, often represented with indistinguishable attributes, was another example of Greek syncretism.

An unquestionably, essentially Thracian religious figure is the Thracian Horseman or Hero, who first appeared in the Hellenistic period in the conventional iconography of a horseman riding slowly towards a goddess, and reappeared in the Roman period, when other iconographic forms were used, especially that of a hunter, usually on small relief tablets suitable for placing in a cave or other sanctuary. These icons, for such they were, often had a strong chthonic character, their votive and sometimes funerary purpose being basically consistent with a religion in which heroisation of a dead ancestor was an underlying theme. Their iconographic debt to Greece is impossible to estimate, especially since almost all known examples are relatively late in date; but association of the Thracian concept of immortality with the Thracian as well as Greek concept of heroisation is supported by the most common inscription: ‘Hero’. The horseman may alternatively or additionally be identified with one of the gods, most frequently Asklepios, but often Apollo and sometimes Dionysos; sometimes there is a Thracian epithet which cannot be surely translated. The icon-like quality of the small stone reliefs has helped to preserve them. Under Christianity they were reinterpreted as representing a new ‘hero’, St George, and in the early years of this century on St George’s Day peasants were still making pilgrimages and bringing sick people to be cured to one of Bulgaria’s main Thracian Horseman sanctuaries, one identified particularly with Asklepios.

NOTES

1. Homer, Iliad IV, trans. Rieu, E. V., The Iliad, Harmondsworth, 1950, 91.

2. Xenophon, Anabasis, VI 1,4.

3. Dremsizova-Nelchinova, Ts., Purvi Kongres na Bulgarskoto Istorichesko Drujestvo, Sofia, 1972, 1,335 ff.

4. Dremsizova, Ts. and Antonova, V., Iz Shoumen 1,1955, 5 ff.

5. Herodotos V,8, trans. Cary, H., Herodotus, London, 1901, 309.

6. Herodotos V,5, ibid., 308.

7. Herodotos IV,94, ibid., 268, 269.

8. Herodotos V,6, ibid., 308.

2 The Black Sea Cities

I. APOLLONIA PONTICA

Apollonia Pontica (Sozopol) was founded by Miletos towards the end of the seventh century. Strabo says the greater part of the city occupied an offshore island, which must have been the present Sveti Kyrikos, but it extended over the Sozopol peninsula and Greeks also settled on the Atiya peninsula, a few kilometres to the north. The site was evidently chosen for its two excellent harbours - the city’s emblem on coins was an anchor and a prawn - rather than trade. Its immediate hinterland was rugged and had no easy routes to the interior. The growing seaborne traffic plying the western Black Sea coast had shown the need for a port of call for revictualling and repairs between the Bosphoran harbours and such wealthy trading colonies as Histria and Olbia, established some half a century earlier farther north.

The Salmydessian coast of south-east Thrace between Apollonia and the Bosphorus had earned an evil reputation from its treacherously dangerous shores and the ferocity of the inhabitants. Aeschylus in Prometheus Bound describes Salmydessos as ‘the rugged jaw of the sea, hostile to sailors, stepmother to ships’. Xenophon goes into more detail:

In this part great numbers of ships sailing into the Euxine get stranded and wrecked since there are sandbanks stretching far out to sea. The Thracians who live here put up pillars to mark their own sectors of the coast, and each takes the plunder from the wrecks on his own bit of ground. They used to say that in the past, before they put up the boundary marks, great numbers of them killed each other fighting for the plunder. Round here were found numbers of couches, boxes, written books and a lot of other things of the sort that sailors carry in their wooden chests. [1]

No wonder Apollonia prospered. The colony, like others, must have had agricultural land, and good profits could be made from servicing storm-damaged shipping, supplying provisions, and providing recreation facilities for the sailors. Thence it developed as a point of transhipment and exchange of luxury goods manufactured in the Greek cities of the Aegean, notably pottery, textiles, jewellery, and wine, for raw materials such as grain, salted fish, hides, and flax from the rapidly increasing number of colonies dotted along the north-western and northern coasts of the Black Sea. Late in the sixth or during the fifth century, Apollonia successfully fostered dependent settlements in its vicinity, the most important, probably, being Anchialos (Pomorie), a valuable source of salt north of the Gulf of Bourgas.

With much coastal erosion and the picturesque tourist resort of Sozopol overlying the original city, opportunities for excavation have been small. A hoard of blunted copper arrowhead currency on the Atiya peninsula may reflect early dealings with the Asti tribe within whose territory the settlement lay, [2] and who almost certainly previously inhabited Apollonia. The earliest relics of the Greek city came to light during the dredging of the harbour in 1927.

33

![]()

![]()

34

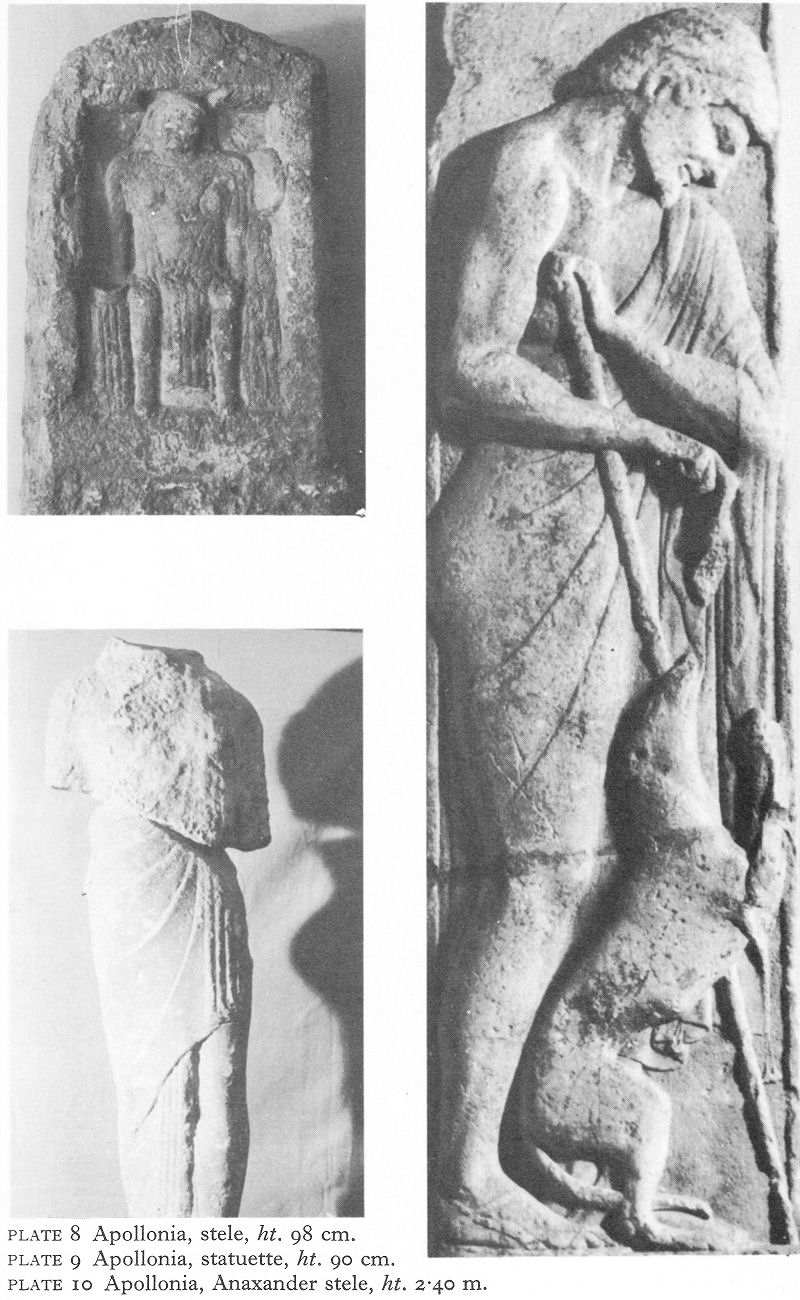

Of the substantial quantity of mostly fragmented pottery almost all the sixth-century pieces were imports from Ionia, Rhodes, and Samos. One complete and fragments of two more funerary stelai, or grave stones, of the same period were also recovered. All three show an enthroned female figure, a Cybele, Demeter, or other ‘great goddess’. In the complete stele (Pl. 8) she appears to be resting a bowl, held in her right hand, on the arm of her seat. The primitive sculptural form is impressive; classic proportions are absent and drapery is indicated schematically. A terracotta figurine ascribed to the third quarter of the sixth century portrays a gracefully proportioned and executed version of a similar goddess. Found on the Atiya peninsula were headless fragments of a fine marble male statuette from the same period possessing a Late Archaic simplicity (Pl. 9).

After the ejection of Persia from Europe in 478 b.c., control of the Black Sea trade passed to Athens and Ionian imports dwindled to a trickle. A chance find in 1895, probably belonging to the beginning of this period, is the funerary stele of Anaxander, identified by a brief inscription at the top, showing a man leaning on his stick and gazing down at his dog, which stretches up on its hind legs to accept something from his hand (Pl. 10). [3] The subject was popular in the Greek world from the end of the sixth century, but, whilst the tall, narrow shape was in vogue during its last three decades, the strong stylistic resemblances with the stele from Orchomenos by Alxenor of Naxos in the National Museum of Athens, which is attributed to the first quarter of the fifth century, suggest the Apollonian stele was Greek work imported in the second quarter of the century. There are still traces of Late Archaic style in the rendering of the hair and drapery, but the peaceful realism and rhythmic composition bring it within the classic tradition.

Athenian commercial instincts were probably responsible for the development of trade with the hitherto neglected interior by such subsidiary colonies as Anchialos and Sladki Kladentsi, a site 3 kilometres west of Bourgas of which the antique name is unknown where two stores of commercial amphorae, large twohandled earthenware containers used for wine or oil, have recently been found. The success of this policy is reflected by finds of fifth-century Apollonian coins as far west as the Stara Zagora region and by the city’s power to commission a colossal bronze statue of Apollo, 30 cubits (13.2 metres) in height, from the famous sculptor Kalamis. The temple of Apollo the Healer, the Milesian patron god, stood, presumably, on Sveti Kyrikos, and fifth-century architectural fragments, among them part of a frieze of rigidly profiled warriors now in the Louvre, [4] may have belonged to this sanctuary. Athenian ascendancy is also reflected in fifth- and fourth-century pottery dredged from the harbour.

Two of the city cemeteries were partially excavated between 1946 and 1949. The major site was part of a necropolis extending for at least 4 kilometres along the road running south from the city. The excavation area, known as Kalfa, is close to the shore about 2 kilometres from Sozopol and now consists of sand dunes, beneath which some 900 graves were uncovered in a strip about 150 metres long and 10 to 30 metres wide. Although the shifting nature of the dunes gave no help in dating by depth from the surface, compensation was provided by stratification; in some places as many as n graves occurred within a depth of 5 metres. The second was a smaller excavation; in an area about 20 metres long and between 10 and 20 metres wide about a hundred graves were found.

![]()

35

Plate 8 Apollonia, stele, ht. 98 cm.

Plate 9 Apollonia, statuette, ht. 90 cm.

Plate 10 Apollonia, Anaxander stele, ht. 2.40 m.

![]()

36

It lay much closer to the old city, by what is now called the Morska Gradina or Marine Gardens. Burials found here began about the middle of the first half of the third century and ceased after about a hundred years. The results of both excavations have been fully published and reflect the fluctuating history of the city and lives of the citizens over several centuries.

Apollonia’s first or Ionian phase is not represented at Kalfa. Graves of this period would have been nearer the city and, since sixth-century stelai have been recovered from the channel between Sozopol and Sveti Kyrikos, they may have been in land now eroded by the sea. Another cemetery may also have existed between Sozopol and the Atiya peninsula.

Chronologically the excavators divide the graves into three main phases: the first, beginning about 460 and lasting a hundred years; the second, from about 360 to 290; and the third, from about 290 to 175. Inhumation predominated throughout, only 11 cremations being noted. The skeletons normally lay stretched out on their backs, arms alongside the body, in the common Greek manner, and were oriented in no particular direction. Wooden coffins were usual, sometimes above them gabled tops consisting, in the case of adults, of four pairs of large square tiles, with similar tiles placed upright to close each end.

Only 22 stone tombs were found. Cists built of cut stone blocks, these were flat-topped and seldom much larger than the coffins. Two children’s graves were built side by side with a surround-wall. The stone tombs belonged to the second phase, the earliest of them being attributed to the mid-fourth century and the majority to the late fourth or early third. Some were re-used, even into Christian times. Eleven older children were buried in pithoi, or large wide-bellied storage jars, and 17 babies in amphorae - these are dated to the second half of the fourth century.

Seven crouched burials were exceptions to the normal manner of inhumation; five had both arms and legs bent up to the chin, in the other two the arms were missing. They are dated to the latter part of the fourth or early third century and may perhaps have been of Thracians who retained their ancient ritual, as happened in Black Sea cities farther north, although among the Thracians generally this form of burial is typical of a much earlier period.

The 11 cases of cremation are also attributed to Thracians. These are dated to the mid-fourth century or later; the body seems usually to have been burnt elsewhere and the charred bones then placed in clay urns, exceptions being a red-figure krater, or deep wide-mouthed bowl for mixing wine with water, and a cylindrical stone urn with a stone lid. One adult cremation was contained in two bowls of about the same size, one upside down serving as a lid. With the much-burnt bones were eight small objects of fired grey clay of different shapes, including a spindlewhorl, a weight, a miniature bowl, a bead, and what was perhaps a primitive figurine, which alone showed traces of burning. These were probably magic objects and occur in some burials elsewhere (p. 64).

The inventories and the value of the grave goods varied from period to period, and significant differences occur between richer and poorer graves. Besides vessels for eating and drinking, the former contained toilet accessories and other luxuries; children had toys. The latter might have only one rough, locally-made pot or nothing at all. Nevertheless, the absence of architecturally outstanding graves is matched by the quality of the goods placed with the corpses.

![]()

37

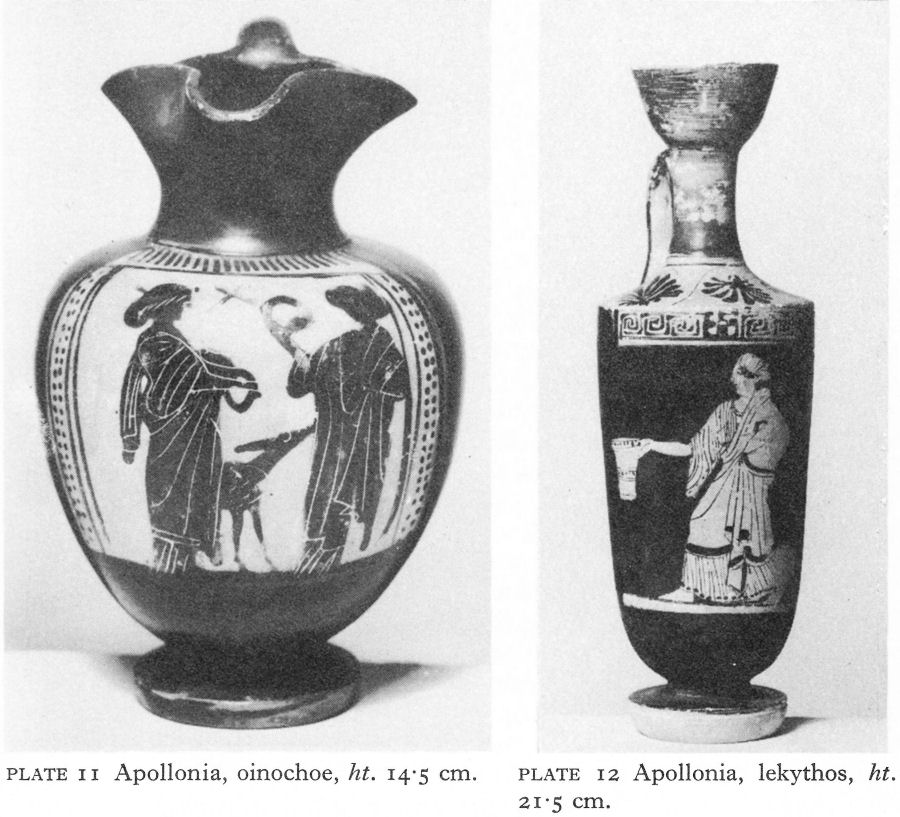

Plate 11 Apollonia, oinochoe, ht. 14.5 cm.

Plate 12 Apollonia, lekythos, ht. 21.5 cm.

Plato would have approved the lack of funerary ostentation shown, but the explanation may be either that the élite of the city were buried elsewhere or simply that the population basically consisted of small traders and middlemen. The relatively little jewellery found, particularly in the earlier graves, may, of course, be due to theft. About 30 stelai were recovered, still above the graves. Most bore no more than the two names of the deceased.

The intensification of trade with the Thracian interior to provide Athens with raw material she could no longer obtain from Asia Minor and the ensuing prosperity of Apollonia are reflected in the funerals of about 460 to 430. Almost all the pottery, averaging some four objects to a grave, although very occasionally reaching a score, was imported from Attica; the few exceptions were probably left over from the Persian occupation. Only one piece of Ionian ware occurs in a grave later than 430. Most of the pots were for everyday use and of little artistic merit. Nevertheless, a black-figure Attic oinochoe, or wine-jug, of about 470 was found in a grave of the second quarter of the fifth century. Made of fine light brown clay, it shows Artemis and Apollo against a light red rectangular ground, the remaining surface being decorated with a black glaze (Pl. 11). There were also a number of red-figure lekythoi, or small narrow-necked jugs for scented oils, generally showing women at their toilet or otherwise occupied in the home, like the lekythos illustrated in Pl. 12, found in a child’s grave and dated to the

![]()

38

third quarter of the fifth century. In a grave of the same date were two blue glass aryballoi, or globular vases; a quantity of black-glaze pottery which included four kylikes, or shallow two-handled wine-cups, turned upside down, evidently a ritual act; two aryballesque lekythoi; and terracotta figurines of Aphrodite, Demeter, and Silenus - two of the last, one of especially fine clay, representing him with breasts, an enlarged belly, and genitals.

The only 80 terracotta figurines discovered all belong to these three decades. Some were toys, but in certain richer tombs they were associated with a ritual hearth, where, after a funeral banquet, animal and fish bones, fruit stones, and pots were tossed on to the bonfire. The custom of breaking pots at a funeral was also a contemporary practice in the Thracian hinterland.

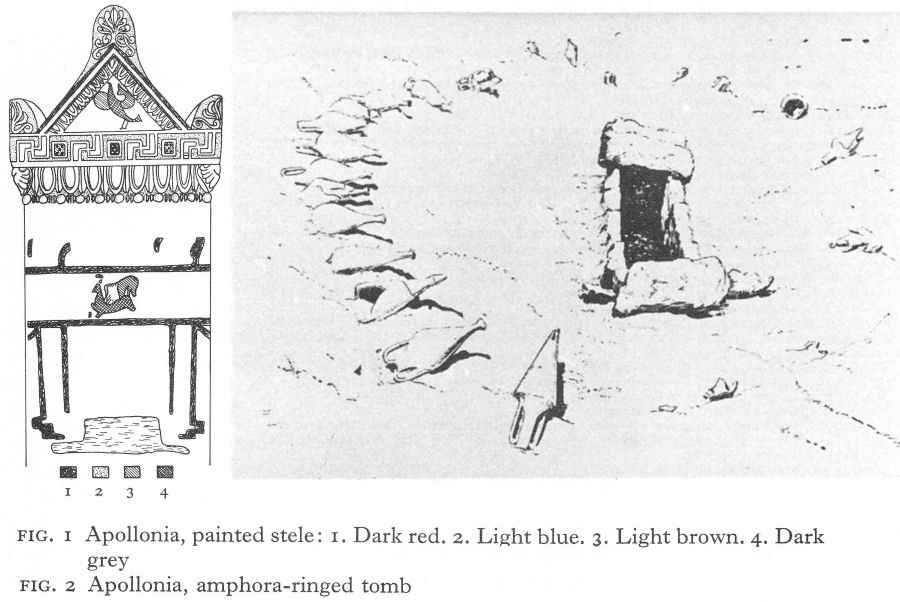

After 430, terracottas disappear and grave goods generally become fewer and inferior in quality, although almost all are still Attic imports. Athenian trade continued, on a reduced scale; not only did Athens have troubles, but, after the death of Sitalkes in 424, the Odrysian state, which had been favourable to Athens and had provided stable conditions for trade, began to disintegrate. Nevertheless, early fourth-century finds include a red-figure bell-krater displaying satyrs and maenads on the front and three youths on the back, which, together with a similar Vase found in a Thracian tumulus in the Mezek area, is attributed by Sir J. Beazley to the Black Thyrsus painter. [5] Also from the first half, probably the second quarter, of the fourth century comes the only painted stele - a sandstone slab 172 metres high excluding the wedge base - found in any west Black Sea city (Fig. 1). The elaborate architectural design on the upper part incorporates a pediment occupied by a picture, probably of a siren.

Fig. 1 Apollonia, painted stele: 1. Dark red. 2. Light blue. 3. Light brown. 4. Dark grey

Fig. 2 Apollonia, amphora-ringed tomb

![]()

39

In the upper part of the stele is a separate area divided off by two [horizontal] red lines, in which a stag is shown, attacked by a lion. Both pictures are much damaged and their details indistinguishable. So far as one can tell, the stag is dark blue and the lion light brown. There are four vertical red lines along the slab which are perhaps the outlines of two columns. Between them at their base is a two-line inscription, illegible because of the perishable nature of the stone but no doubt the name of the deceased. Above the red horizontal lines are other traces of red ornament. [6]

The middle of the fourth century saw a revival in Apollonian prosperity, but there is some evidence of trouble in the unusual feature of a number of mass burials without grave goods. They may have been due to a natural disaster, but could have been connected with the Macedonian arrival. Apollonia entered into an alliance with Philip II, who successfully exploited Thracian disunity to reduce the Odrysai and their rivals to varying degrees of subjection. However, the archaeological evidence from the Kalfa necropolis suggests that the city’s brief renewed prosperity was between the years 360 and 340 - before the peak of Macedonian power - when Athens was making fresh efforts to exploit the Thracian trade, her commerce interrupted with Egypt as well as Asia Minor. To these two decades are attributed many flamboyantly decorated ‘Kerch-style’ vases; these were mostly lekythoi, often aryballesque, but included other forms as well. Manufactured in Athens between 380 and 310, largely for the Scythian and Thracian export market, the polychrome colouring, extending to the use of white, blue, pink and even gilding and barbotine work, hardly conformed to Athenian taste. The subjects were preponderantly domestic scenes from the women’s quarters, often including Eros. Others showed children with toys or the household dog, youths in the gymnasium, and scenes from Greek mythology with an apparent emphasis on Dionysos. A large lekythos depicting Demeter, Persephone, Triptolemos, Dionysos, and Hermes is an example of a group of vases especially associated with Apollonia. [7]

The next half-century, beginning about 340, saw the slow decline of the city. Until 320 the Kerch-style lekythoi continued to be plentiful, but thereafter all imported objects became noticeably fewer. With the ascendancy of Macedonia and Alexander’s ejection of the Persians from Asia Minor, the links with Athens inevitably weakened. Amphora stamps suggest intensified trade with Heracleia Pontica during the second half of the fourth century, no doubt an attempt at diversification; but by its last quarter the regular use of ships capable of the direct north-south sea route across the Black Sea had undermined the foundations of Apollonia’s economy. The city’s first bronze coins were minted in 350 and soon they replaced silver ones in many graves.

Aristotle in his Politeia quotes Apollonia as an example of factional dispute following the admission of new settlers into a city. Whence and when these came is not specified, but during this half-century there are signs of the lowering of barriers between Greeks and Thracians. Thracian fibulae, or brooches, appear for the first time in the necropolis in the second half of the fourth century, as well as the fragile funerary garlands of gilded clay grapes or raspberries, rosettes, and ivy leaves that were fashionable among Greeks and Thracians alike towards the end of the century,

![]()

40

and there is a sudden profusion of local pottery. During the whole period between 360 and 290 about a quarter of the clay vessels found in graves are local work, including painted clay imitations of the earlier alabaster or glass Egyptian-type alabastra (small vases for unguents or perfumes). After two centuries of importing everything but rough kitchenware, Apollonia had to fall back on its own or other local resources.

A funerary ritual unique here is attributed to this period. In a circle of 7 metres in diameter enclosing a stone-built tomb, 27 amphorae were arranged, mouths outwards, level with the roof of the tomb (Fig. 2). Inside the tomb only a grey clay pot and a fragment of a bronze strigil, or perspiration scraper for use by athletes and after bathing, accompanied the skeleton. Thirteen of the amphorae were fairly well preserved and, whilst without stamps, are considered to be Thasian types of the second half of the fourth or the beginning of the third century. A similar circle of amphorae was found nearby in a very early dig; another occurs round a cremation burial at Olbia.

The third stage of Apollonia’s existence marked by these graves began about 290, about three-quarters of the way through the long reign of Lysimachos. The Greek colonies now served as garrison towns and at the end of the fourth century and the beginning of the third graves of soldiers, buried with their weapons, occur. Now, too, a new burial ritual appears, in which the coffined body and grave goods are placed in an immense earthen jar.

By the end of Lysimachos’ reign in 281, Apollonia, politically and economically, had fallen behind the neighbouring Megarian colony of Mesambria. The Celtic invasion and occupation of much of south-eastern Thrace was a further blow. Apollonia was not captured, but a fragmentary inscription in Doric dialect found in the city is generally interpreted to mean that it had been forced to join Mesambria to seek from Antichos II Theos aid against the Celts. [9] Contemporary inscriptions from Mesambria, Kallatis (Mangalia), and Histria refer to the granting of proxeny or honorary citizenship to Apollonians, suggesting a possible exodus of some of the wealthier and more timorous.

During the final phase represented in these excavations, the Kalfa site must have been too distant from the city and the Morska Gradina cemetery came into use. From here came one of the very few carved stelai. Third-century in date and probably commemorating a warrior killed in battle, [10] it shows a young man with two spears in his left hand and his right resting on a herm, a quadrangular pillar, usually decorated with genitals and surmounted by a bust. The inscription below is almost entirely lost (Pl. 13). The stele was not connected with any known grave.

Many Morska Gradina graves of between the second quarter of the third and the second quarter of the second century had no grave goods at all. In a few, some imported objects, such as Megarian bowls and some gold ornaments, were found, but almost all the pottery was local. Tile-roofed graves continued. A relatively rich cremation burial may indicate the status achieved by Thracian members of the community.

The liquidation of the Celtic kingdom in 218 revived the old antagonism between Apollonia and Mesambria. According to an Apollonian inscription, of which a fragmentary copy was found at Histria, at some time in the first half of the second century Mesambria captured Anchialos and then its fleet, suddenly

![]()

41

appearing before the walls of Apollonia, looted and profaned the temple of Apollo, although failing to take the city. The rescue of Apollonia and the defeat of Mesambria with the aid of forces from Histria is also recorded. [11] Apollonia was among the cities allied with Mithridates of Pontos against Rome in the first century, probably playing only a modest part. Fierce resistance to the Roman forces under M. Terentius Varro Lucullus in 72 b.c. is said to have brought destruction on the city and its fortifications. Pliny relates that the ‘tower-like’ bronze statue of Apollo by Kalamis that for four centuries had symbolised the greatness of Apollonia was shipped to Rome to adorn the Capitoline.

II. MESAMBRIA

Towards the end of the sixth or at the beginning of the fifth century the Milesian monopoly of the west Black Sea coast was broken by a Megarian settlement. Mesambria or Mesembria Pontica (Nesebur) - both names were used in antiquity - was probably a foundation of the earlier Megarian colonies of Byzantion and Chalcedon on the Sea of Marmara. Its present name has evolved with little change from that given it by the Greeks and Thracians.

North of the Gulf of Bourgas and immediately south of the last eastern spur of the Stara Planina, the colony occupied a peninsula now only 850 metres long and 300 metres wide, linked to the mainland by an isthmus so low and narrow that artificial banking was needed to make a modern road. Steep cliffs, subject to erosion, protect the north and east coasts, but on the south the land slopes gently to the sea. The situation offered easier access to the interior than Apollonia possessed, as well as fairly low and easy passes facilitating trade with the north.

The colony was probably the result of a succession of migrations from the Persian threat, which may account for a more independent economic development than that of Apollonia - one of a planned series of settlements in a time of peace. By about the middle of the fifth century economic prosperity was shown by the issue of coins. Naulochos (Roman Templum Iovis, modern Obzor), just north of the Stara Planina, was an early offshoot of Mesambria.

No major excavations have taken place in modern Nesebur, with its confined, densely populated area and its long history as a busy maritime town. But 20 relatively large-scale soundings between 1944 and 1964 have identified three distinct cultural layers prior to the Turkish period. The earliest was Thracian; it included both Bronze and Early Iron Age material, but extended over only part of the peninsula and varied from 20 centimetres to 2 metres in depth. Next, several metres thick and overlying the whole peninsula, was a Greek layer, distinguished by its pronounced yellow colour, caused by the disintegration of the mud bricks used to build houses. The third layer contained remains from the Romano-Byzantine period. Large stretches of the original Greco-Hellenistic ramparts have fallen into the sea or been otherwise destroyed, but short sectors, particularly near the isthmus, have been excavated. At the site of a necropolis which stretched several kilometres along the coast towards the south-west, there has also been some excavation, although, apart from early chance finds, these have been mostly salvage digs before refugees were housed here in the 1930s.

There is little doubt that the Greek colony was encircled by a fortified wall at an early stage. Almost all the north-eastern sector and perhaps also an acropolis have been eroded.

![]()

42

Plate 13 Apollonia, stele fragment, ht. 36 cm.

Plate 14 Mesambria, pre-Hellenistic city wall

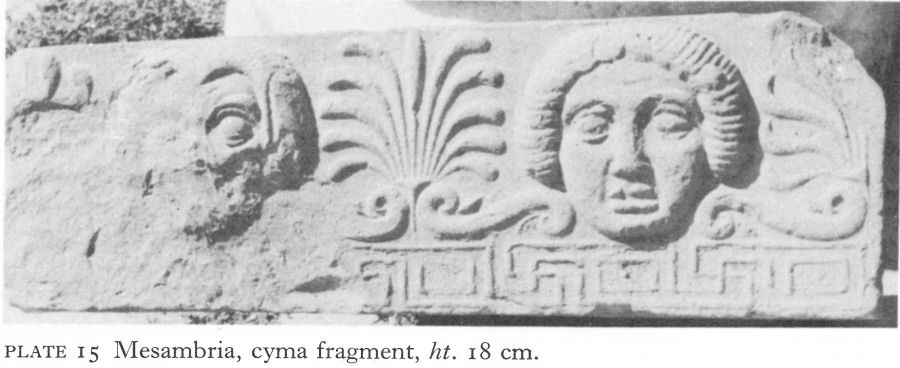

Plate 15 Mesambria, cyma fragment, ht. 18 cm.

Some slight impression of the damage can be gained at the site of the Sea Basilica, the north nave of which now lies at the bottom of a sheer cliff (Pl. 189). The narrow western shore facing the mainland has been more fortunate in suffering only from man.

Here the gateway, through which runs the road into the town, dates from the Romano-Byzantine period, but some remains of the earliest ramparts have been excavated nearby, following a line very close to the later walls. The lowest and first building period is dated to the fifth or, at latest, early fourth century. With foundations 2 metres deep, the outer fapade is dry-stone walling, generally using ashlar blocks of varying size, irregularly laid, but here and there strengthened by hooking one block into its neighbour, or, more rarely, laid in regular courses of unequal height. In the second building period, tentatively assigned to the fourth century, the isodomic method was used, the courses regular and of equal height. In the third period, stability was ensured by laying the blocks in courses to expose long sides and ends alternately, a system to gain added strength

![]()

43

perhaps introduced by the end of the fourth century, but common throughout the later Hellenistic era. This substantial facade was backed by an emplecton, or fill, of broken stone and yellow clay like that used for the bricks of the houses. As only parts of the emplecton have survived and nothing of the inner facade, the thickness of the wall is unknown. There were also no signs of towers. A short distance east of the Byzantine north-west angle tower an early sector of the north ramparts was found. Finely jointed ashlar blocks, rectangular or trapezoidal in shape, are laid without mortar in nearly even courses, with some of the blocks hooked to the next. The emplecton contained fragments of archaic Attic pottery and this wall is regarded as another sector of the original fortifications (Pl. 14). A later repair made use of a fourthor third-century Doric capital.

Soundings located several houses in the Greco-Hellenistic layer; the earliest, attributed to the fifth century, has still to be published. Building levels were distinguished by superimposed floors with evidence of habitation between them. Four Hellenistic houses had peristyles, probably with wooden pillars, and stood apart from their neighbours. Outside walls were coated with a plaster of fine lime and sand, with painted decoration in various colours, including Pompeian red, yellow ochre, green, and black. About a quarter of one Hellenistic house was excavated. Fragments of black-figure vases and sixth-century Chian amphorae were found beneath the floor, together with part of an inscription mentioning a sanctuary of Apollo. The excavated sector consisted of an irregularly paved and peristyled rectangular courtyard and rooms on the north and east sides. In the north wing a stone staircase with six steps making a right-angled turn descended into a cellar with stone walls 2-20 metres high. The debris of the collapsed upper parts of the house consisted of tiles, decomposed mud bricks, and fragments of stucco, painted red, blue-black, white, and in imitation of marble. There were also Mesambrian coins of the fourth to second centuries, terracottas, and ceramic fragments, including a mould for a ‘Megarian’ bowl. Built towards the end of the fourth century, the house was apparently reconstructed in the second. An interesting point about some of the building materials is an almost certain link with Olbia, a link also shown by decrees erected in the latter city. Fragments of fourthcentury Mesambrian cymata, or curved architectural mouldings, bear the same stamp as is found on Olbian tiles and, on the basis of Mesambrian material, much of it unpublished, I. B. Brashinsky recognises close analogies between cymata and ornamental frontal tiles of both cities (Pl. 15). [12]

Although some building material may have been imported, Mesambria possessed its own industries, to a much greater degree, on present evidence, than Apollonia. Besides finished objects, remains of two furnaces were discovered close to the Hellenistic house. The remnants of one, together with the discovery of a ‘Megarian’ bowl mould in the nearby house, suggest that it was a pottery kiln. The construction of the better-preserved furnace, the quantity of slag in its vicinity, and holes in the ground suitable for melting ingots, all pointed to a metallurgical purpose.

Close to the house and furnaces was the bothros, or sacrificial pit, of a temple. The contents, dating from the fifth to the third centuries, included fragmentary inscriptions which indicate a sanctuary of Zeus and Hera. No early public buildings have yet been found, but epigraphic evidence shows that the chief temple was dedicated to Apollo, probably Pythian Apollo,

![]()

44

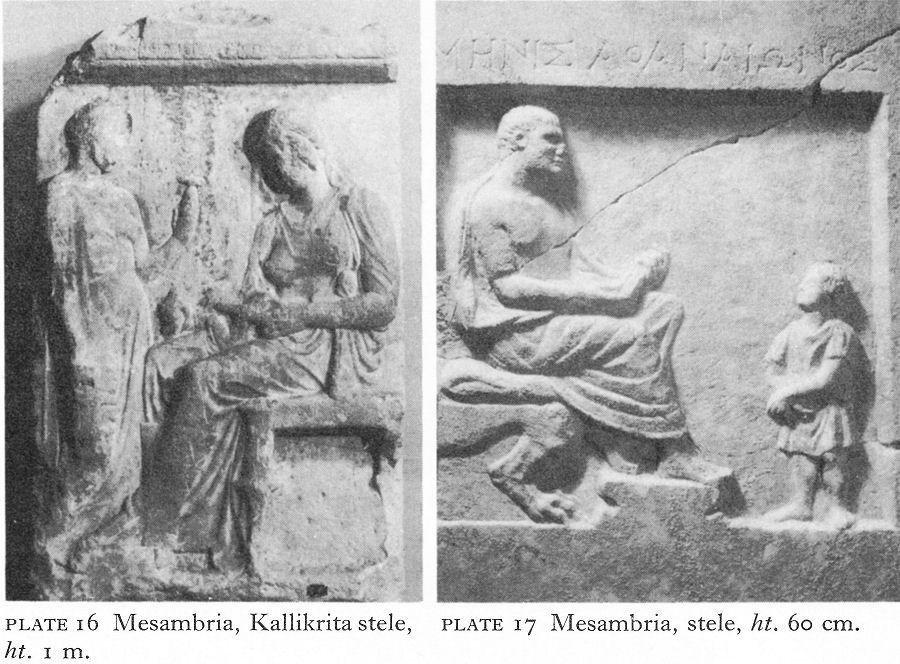

Plate 16 Mesambria, Kallikrita stele, ht. 1 m.

Plate 17 Mesambria, stele, ht. 60 cm.

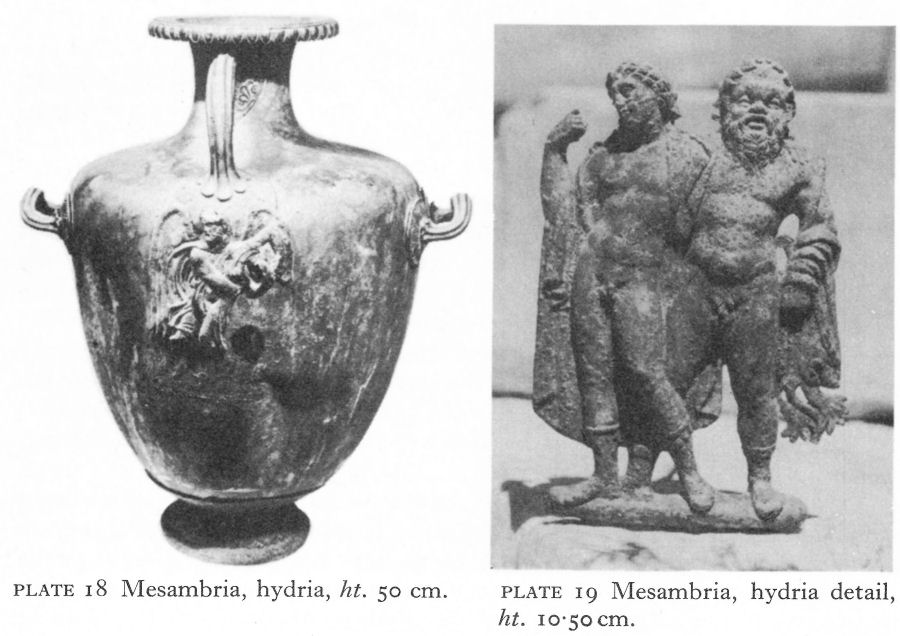

Plate 18 Mesambria, hydria, ht. 50 cm.

Plate 19 Mesambria, hydria detail, ht. 10.50cm.

![]()

45

much honoured in Megarian colonies and to whom was addressed a second- or third-century a.d. votive tablet of the Thracian Horseman found in the city. Dionysiac rites are attested by several inscriptions. Two, one of which had been erected in the temple of Apollo, refer to the ceremonies taking place in the city’s theatre. Other inscriptions indicate special attention to the cults of Athena Sotira, Demeter, Hekate, and the Dioskouri. From the third century onwards, and especially about the first century b.c. when the presence of refugees from Egypt offers a ready explanation, there are references to Isis and Serapis.

Aspects of Mesambrian life touched upon in other, mostly fragmentary inscriptions, include a probably third-century decree declaring free entrance to the harbour in times of peace or war; a treaty with a Thracian chief, Sadalas (p. 48); praise of a person who provided grain cheaply to the Mesambrians; and a late third-century decree honouring a woman, unfortunately so fragmentary that both her name and her virtues remain unknown. It is the earliest official honour paid to a woman found on the west Black Sea coast and an unusual feature at this time in a Greek city.

The approximate site of the mainland necropolis has long been known. More than fifty years ago, I. Velkov wrote:

Over an extent of 2 to 3 kilometres the whole area is strewn with broken stone and brick and fragments of antique pottery. In some places there are larger accumulations of such fragments and more massive stones. Antique coins are always to be found here, especially after a spell of strong wind. [13]

Large numbers of the burials were direct interments into the earth and in an area subject to constant weathering and habitation through the ages they were easily destroyed. By 1964 less than a hundred tombs had been identified, most through chance or the salvage digs of the 1930s. They were mainly inhumations of the fourth and third centuries, laid in variously oriented rectangular tombs, little larger than coffins, built of thick stone slabs smoothed on the inside but only roughly shaped on the outside; horizontally laid slabs formed the roof. Exceptions included a gabled tomb, like those at Apollonia but with two large limestone slabs balanced over the corpse instead of tiles, and double tombs, divided merely by a partition wall. Another possessed a small ‘antechamber’ with closed walls of three single slabs attached to the main compartment with no facility for intercommunication. Robbers had removed the grave goods, but charred embers and burnt potsherds in the ‘antechamber’ suggest a sacrificial purpose. Similar tombs were found in Thracian cemeteries in north-east Bulgaria. The tomb with the richest grave finds (see below) was also one of the largest (3 metres long, 1.60 metres wide, and 1.20 metres deep). The limestone blocks were more carefully dressed than usual, being smoothed inside and out.

The earliest funerary stele - that of Kallikrita - was found re-used south of Nesebur, in the village of Ravda. In spite of its damaged condition, the subject of a seated woman amusing a child with a toy and watched by a female attendant holding up an alabastron in her left hand and carrying a basket in her right, is portrayed with sympathy and dignity (Pl. 16). The Attic theme of the seated woman and her attendant, at its finest exemplified by the stele of Hegeso in the National Museum of Athens, was popular all over the Greek world. It is likely that Kallikrita’s stele, undoubtedly provincial work, was carved in a Mesambrian

![]()

46

workshop of the end-fifth or early fourth century. Three stelai bearing reliefs of a kantharos, or drinking cup, the earliest attributed to the second half of the fifth or beginning of the fourth century and the latest to the third, also come from the necropolis.

Another popular Attic subject was that of a teacher and his pupil (Pl. 17). Again, in this mid-third-century provincial version, stiff, a little disproportionate, and with an exaggerated zoomorphic chair leg, something of character comes through in the two personalities.

In some third-century graves, remains of clay ‘fruit’ garlands like those in Apollonia were found. A more appropriately Mesambrian grave find was the Megarian-type bowl; the quality of clay and workmanship of those recovered suggest local work.

Considering the extent to which the cemetery was robbed in antiquity and later, it is surprising that three bronze hydriai, water vessels with two horizontal and one vertical handles, have been preserved. One had served as a cremation urn; it was decorated with a bronze relief of the rape of Oreithyia by Boreas (Pl. 18). This motif was repeated on another, whilst the third showed the young Dionysos accompanied by Silenus (Pl. 19). Although sometimes used for cremations, these vessels were primarily valuable water jugs, coming within the category of expensive wedding gifts, as when Pseudo-Demosthenes refers to one ‘alongside a flock of fifty sheep, with the shepherd and a serving boy’. G. Richter, analysing a group of 20 such hydriai, concluded that they originated from a single workshop in the second half of the fourth century. [14] According to her, the source may have been Attica; Chalcedon has also been suggested. [15] The discovery of three in a site so little excavated could be due to chance, but is more likely to indicate either an origin closely connected with the colony or a successful export-import policy. More than a score of bronze hydriai of other types have been found in wealthy Thracian graves in the interior.

There was probably little time lost between burial and the surreptitious removal of the richest grave goods. The construction of the stone tombs made robbery easy. As the most valuable objects were usually placed near the deceased’s head, once the grave had been located or if the ceremony had been watched, it was only necessary to take up one roof stone to secure the major booty.

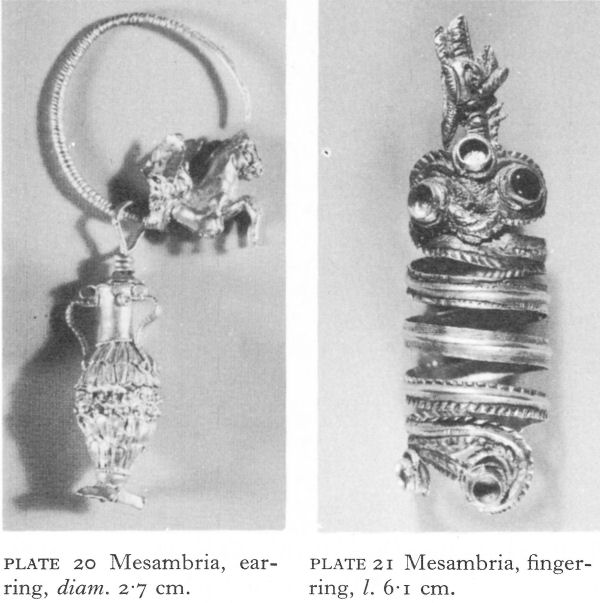

The large tomb mentioned above is one of the very few found intact, perhaps because of its superior construction or because it was originally covered by a tumulus. It contained the skeleton of a woman; fragments of fine gold thread all over the interior suggest that she wore or was covered by a rich textile. Besides three pots of local coarse ware and the ritual fragments of a stamnos, or jar for mixing wines, commonly found in these tombs, and three glass alabastra, there was a rich collection of gold jewellery, mainly of well-known Hellenistic types. There was a chain necklace with finials shaped like animal muzzles and enclosing opals, and beads from at least two others, one of glass. The finest workmanship was evident in a pair of earrings - in which one end of the hoop terminates in the foreparts of Pegasus and from the hoop is suspended a miniature amphora with elaborate filigree and granular decoration (Pl. 20). The earrings had been much worn and the wings of Pegasus were damaged; one had been repaired, not very skilfully, with a different, paler gold.

The most unusual of several rings was found on the skeleton’s finger - a spiral with a fantastic beast’s head with crocodile jaws at the top (Pl. 21).

![]()

47

Plate 20 Mesambria, earring, diam. 2.7 cm.

Plate 21 Mesambria, finger-ring, l. 6.1 cm.

Three jewels, of which one amethyst remains, were inset in clumsily stylised shoulders and two more at the base of the spiral. This development of the common snake-spiral ring, an example of which was also found in Mesambria has few if any analogies in either Scythian or Thracian animal art. Also unusual was an oval brooch just over 8 centimetres across, to which was welded a bronze pin. Ornamented with a well-designed filigree decoration and inset with seven stones, it was of a type found elsewhere in this cemetery, but usually simply decorated by a mythological scene hammered on a mould without especial skill.

Near this tomb were several others, partially robbed or badly damaged, and two tumuli, suggesting that this isolated part of the cemetery was used by wealthy Thracians living in the city. The opulent grave goods, contrasting with those of Greek tombs, probably reflected not only Thracian belief in an afterlife in which one’s most precious possessions would be needed, but also a belief in the power of ancestors over the living.

The use of the pale gold noted above extends to the manufacture of at least nine ornaments found in Mesambria, including the moulded oval brooches. In one case it has been suggested that, lacking the correct matrix, the craftsman combined two others to achieve the semblance of a Nike, or Victory. The nature of these various jewellery finds suggests the likelihood of a goldsmith’s workshop in Mesambria by some time in the third century.

In spite of the mention of unpublished fragments of fine imported and local pottery among the debris of buildings and the representations of kantharoi on stelai, remarkably little ware of any artistic value is known.

![]()

48

An exception is a red-figure bell-krater, almost identical in shape to others found in Apollonia and Odessos; it shows a young girl being conducted towards Dionysos and erotes, a dancing satyr in attendance.

Little is known of Mesambria during the Macedonian period, although it was at this time that the city replaced Apollonia as the leading Greek colony on the south-west Black Sea coast. Doubtless access to the Getic areas north of the Stara Planina was an advantage, but probably the traditional adaptability of its citizens, shown by their mutually satisfactory relations with the Thracians in the hinterland, was a basic factor.

A partially preserved decree throws some light on Mesambrian-Thracian relations. Erected originally in the temple of Apollo but being carefully housed by a Nesebur dentist when brought to the notice of archaeologists in 1949, the decree records a treaty between the city and a Thracian ruler, Sadalas. [16] A rendering of the fragment reads:

... to Sadalas as soon as possible. Sadalas must be crowned with a gold wreath during the Dionysiac festivals at the theatre as a benefactor to the city. To him and his heirs will be granted citizenship - the right to represent the honour of the city; to take first place at the public games; to bring his ships in and out of the harbour of Mesambria without hindrance; to be crowned every year with a wreath of the value of fifty staters. The treasurer must write the oath and the agreement on an inscribed slab and place it in the sanctuary of Apollo near the tablets of the ancestors of Sadalas, Mopsuestis, Taroutin, Medistas and Kotys. Agreement between Sadalas and the inhabitants of Mesambria: if a Mesambrian ship is wrecked at sea off the territory of Sadalas, having delivered its cargo . . .

The names of Sadalas and his ancestors are Thracian. The courteous formula of a ‘gold wreath’ was a euphemism for a fairly substantial annual tribute. The inscription is adjudged ‘careful work of the early Hellenistic period’, [17] but in the absence of sufficient comparable local material, no more precise dating is possible on epigraphic evidence. Nor can Sadalas be identified with any certainty. It is a common Thracian name and he could have been a local Astian ruler or an Odrysian. Thus dating to a large extent depends on the period when a Thracian could have been sufficiently influential and powerful to have such relations with and receive such tribute from Mesambria. G. Mihailov considers this could only have been between the death of Lysimachos in 281 and the Celtic arrival in 278. [18] Other scholars have either minimised the power of the Celts [19] or felt that the reign of Lysimachos need not be excluded. [20] The existence of Seuthopolis, albeit some distance inland, may be cited in support of each view.

Archaeology does not record undue hardship in Mesambria in the third century. The teacher and pupil stele (Pl. 17) probably represents local work and an epitaph stylistically influenced by the Iliad may also suggest a degree of cultured leisure. The same necropolis continued in use.

In the second century, Mesambrian ambition led to the attacks on Anchialos and Apollonia already described. But when M. Lucullus arrived at the head of a Roman army in 72 b.c., Mesambria seems again to have adapted to circumstance. While Apollonia resisted, here there was no struggle; the next spring the city erected a decree in honour of Gaius Cornelius, commander of the Roman garrison.

![]()

49

Fierce resistance to Burebista’s Daco-Getic invasion is, however, recorded. Dio Chrysostom says that all the Greek cities south to Apollonia were captured, but judging by votive plaques to the protecting gods, Mesambria may have escaped, and certainly the city survived, perhaps little harmed, into the Roman era.

III. ODESSOS

Odessos (Varna) was founded by Miletos about 585 or 570 b.c. From the beginning, it was essentially a trading colony. Among Greek coastal cities between the Stara Planina and the Danube delta it was second in importance to Histria in the northern Dobroudja, until the latter’s decline, when first place was taken by the later Doric foundation of Kallatis, also in modern Romania. Other colonies included Kruni, by some authors identified with Dionysopolis (Balchik) renamed after a statue of Dionysos had been ‘miraculously’ washed up on its shore, a precedent later followed by some famous Byzantine icons, and Bizone (Kavarna). Excavation and published finds of early date from these and other sites have as yet been minimal. There were also Thracian coastal settlements.

Although dredging operations or soundings showed Bronze Age life under Apollonia and Mesambria, Odessos and its immediate vicinity go back archaeologically to the Late Chalcolithic period and beyond. Lake Varna, around which many pile settlements had been built, was an inlet of the Black Sea until about the beginning of the first millennium b.c., but the silting-up of the bar still left an excellent harbour. When the Greeks arrived, the region was inhabited by the Krobyzi tribe, a branch of the Getai, with whom Milesian Histria had already established good and profitable relations. The hinterland was fertile, well forested, and rich in game.

Today, Varna is Bulgaria’s third most populous city and her chief port. Even during the Roman period the walls were extended to include an area more than double the original settlement of some 13 hectares, and this involved the demolition of Greek and Hellenistic public buildings. In such circumstances, archaeology has always been severely hampered. Sufficient vestiges of the Greek curtain walls have been identified to show that they formed a basis for at least part of the Roman fortifications. Within the early walls, sites of only two preHellenistic buildings have been located.

Outside, chance finds and salvage digs over the last 90 years have traced the outlines of the two main early cemeteries; both were used until the mid-first century b.c. for both cremation and inhumation burials. One stretched northeast along the old road to Dionysopolis, covering the whole 44 hectares of the modern Morska Gradina by the seashore; the other, smaller but densely packed with graves, was near the north shore of Lake Varna. Another, apparently less extensive area north of the city was also used for burials. Three other cemeteries in the neighbourhood are specifically attributed to Thracian villages, rather than the Greek city. Two had several high mounds, excavated by K. Škorpil before they disappeared beneath modern Varna; the third consisted of low mounds now transformed into vineyards.

Škorpil is an honoured name in Bulgarian archaeology. Two brothers, Hermenegild and Karel Škorpil, were idealistic Czechs who, when Bulgaria

![]()

50

gained independence in 1879, decided to help the newly free Slav country discover, understand, and preserve its past. The elder, Hermenegild, came first, and by 1882 Bulgaria’s first archaeological society was founded in Sliven, close to where so many major prehistoric tells have since been discovered. In Varna, where a similar local society was formed a little later, Karel, the greater archaeologist, took the lead in building up an archaeological museum. On countless journeys of exploration he also made many important discoveries, especially in north-east Bulgaria, where an outstanding contribution was the identification of Pliska, the first capital of the medieval Bulgarian state. No less important to science was the stimulus he gave to local appreciation of the heritage of the past and the consequent founding of civic archaeological societies and museums. This did not endear him to those archaeologists and officials whose aim was to build up a collection of ‘treasures’ for a national museum; to them Karel Škorpil’s individualism, his interest in sites (as opposed to objects of silver and gold), and the enthusiasm with which he infected local societies seemed often obstructive. He also antagonised - and fought - developers interested in land only as marketable property, those who viewed ancient monuments as cheap quarries for building materials, and people primarily interested in selling finds abroad to the highest bidder. Škorpil’s contribution to Bulgarian archaeology is incalculable and it is warming to see it now recognised. The village where he made one of his last discoveries, an Early Byzantine basilica with a fine mosaic floor, has been renamed Shkorpilovtsi; he was buried at the site of another basilica he had found, at Djanavar-tepe, near Varna. In the city itself, the Archaeological Museum, with its tradition of scientific archaeology and fine collection, is Karel Škorpil’s main memorial.

The two early buildings within the city were probably cult edifices. In the first, the remains of a wall 1 1/4 metres thick were traced for 9 metres; on part of another wall at right-angles to it was the base of a Doric column with empty spaces for four others. This may have been the pronaos (porch or vestibule) of a temple. Even less was left of the second building, found below the ruins of a Hellenistic temple. It is thought to have been the temenos, or sacred precinct, of a temple of Demeter, the main evidence being pottery from the end of the sixth century and beginning of the fifth from three bothroi which bordered the supposed sanctuary.

The layer above this suggested temenos of Demeter provides some archaeological evidence of Hellenistic cults. [21] Here were the remains of an almost square dry-stone walled building (4.30 by 4.20 metres) with a single entrance. Potsherds attest its fourth-century construction, although there were later repairs. To the south of the sanctuary a well, an oven, a bothros with fragments of amphorae, a herm, and black-glaze ceramic were found, together with two marble votive reliefs. On one relief is a goddess with a quiver of arrows over her shoulders, a patera, or saucer-like dish often used for libations, in her right hand and two (?) spears in her left. A tiny male worshipper stands at one side and a dog sits below the patera at the other. The relief is dedicated to Phosphoros (the light-bearer), an epithet applied both to Artemis-Bendis and to Hekate. On the basis of the inscription this relief is dated to the third-second century [21] or to the second-first. [22] The other relief, attributed to the second century, shows a horseman advancing in a stately manner towards a standing figure.

![]()

51

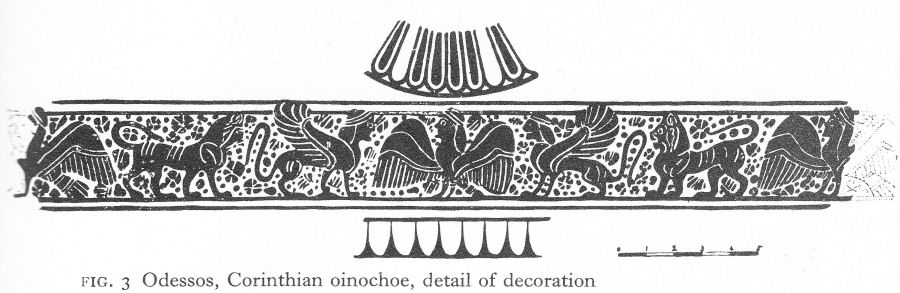

Fig. 3 Odessos, Corinthian oinochoe, detail of decoration

Beneath is a short dedication to the ‘Heros Karabazmos’, a Thracian epithet which also appears on a number of Horseman tablets found in the sanctuary of a Thracian settlement at Galata, n kilometres south of Odessos.

Another syncretism was the ‘Theos Megas’, the Great God, probably Zalmoxis, later known as Darzalas, who also had a temple at Histria. Depicted on coins and represented by terracotta figurines in tombs from the fourth century onwards, the Great God of Odessos seems to have possessed the attributes of a chthonic fertility god. On both coins and statuettes he holds a cornucopia and a patera, on the statuettes often wearing the ivyor vine-leaf crown of Dionysos. Coins of the third century in particular frequently portray him on horseback, possibly an identification with the Thracian Hero and another pointer to the close links between Odessos and its Getic hinterland. A first-century b.c. list of the priests of the Great God of Odessos included a Thracian name and, during the Roman period, games known as ‘Darzaleia’ were held in his honour.

The interrelations of Thraco-Odessitan cults, which appear to centre on the Great God, are by no means clear. Their associations probably included the Samothracian mystery cult of the Kabiri, which flourished in all the northwestern colonies as well as in the interior (p. 96). Epigraphical evidence of the local Samothracian cult appears not only in a third- or second-century inscription found in Odessos, but seems to be implied in one on Samothrace itself. [23]

The earliest pottery found in Odessos consists of five Corinthian vases dated to about the first quarter of the sixth century. An early chance find and the only Corinthian ceramic found in Bulgaria, they probably came to Odessos as articles of trade through an Ionian intermediary. The main decoration of a trilobed oinochoe, a band of heraldically arranged mythological winged creatures and lions, is finely executed (Fig. 3).

Sixth-century Ionian pottery is rare and mostly in fragments; one shows a stylised hunting scene with brown figures on a light background. Two lekythoi are decorated with bands of black glaze on a yellow-brown background. An unusual fragment, attributed to fifth-century Ionia, is the broken-off neck and mouth of an amphora, decorated Janus-like on each side of the handles with the face of a bearded satyr, the hair indicated by small stamped circles.

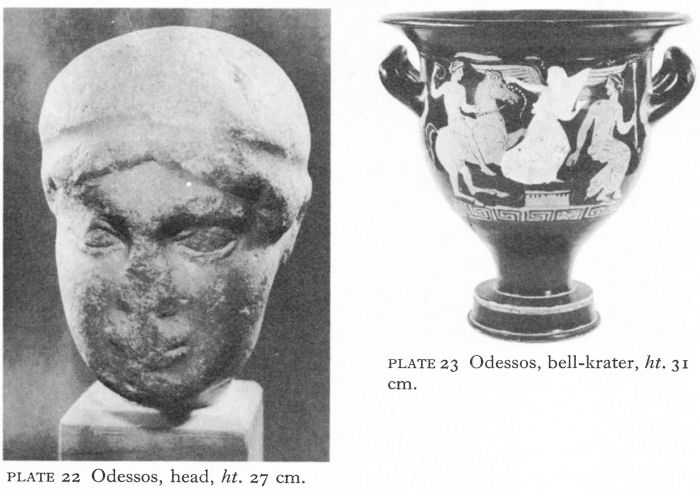

Of greater artistic importance is a head dated to the first half of the fifth century (Pl. 22). The use of local marble demonstrates the existence of an Odessitan workshop. The head, which was intended to wear a diadem or crown, may have represented Apollo.

Isolated finds from the necropolis areas reflect dependence on Attic imports from the beginning of the fifth century, although the earliest object found in situ cannot be dated before the century’s end.

![]()

52

Plate 22 Odessos, head, ht. 27 cm.

Plate 23 Odessos, bell-krater, ht. 31 cm.

In two cases, a black-figure lekythos and a black-glaze olpe, a jug with an even rim and no spout, identical finds occur in fifth-century tumuli at Douvanli and near Stara Zagora, but such parallels do not necessarily imply an Odessitan source; similar vases were found at Apollonia and Attic pottery was then an important item of trade for all the Greek colonies.

Fourth-century finds reflect the popularity of the Kerch-style vases. One, a bell-krater, depicts on one side a horseman crowned by a Nike and watched by a seated youth holding a torch and on the other three young men, one holding a strigil; it contained partly burnt human bones (Pl. 23). The vase, dated to the middle or third quarter of the fourth century, is ascribed to the painter of two Ferrara vases whose work has also been identified at Apollonia, at Olynthos, and in south Russia. [24] Women’s heads are a popular decoration on lekythoi.

There is no mention of any use of Odessos by Philip II or Alexander, although its potentialities as a base for controlling the Getai seem obvious. Both reigns in general increased the trade and prosperity of the city and its Thracian neighbours. The rule of Lysimachos was more oppressive; taxation increased and Odessos, like the other Greek cities, had to support a substantial garrison. In 313, the leading city of the region, Kallatis, led a general revolt against the Macedonian garrisons, with the hope of Odrysian and perhaps Getic support. However, although Kallatis resisted for a long time, quick action by Lysimachos achieved the speedy surrender of Odessos and Histria and ensured the allegiance of the Getai.

It is doubtful if the area north of the Stara Planina suffered much from the Celtic kingdom, but ‘barbarian’ pressures from the North were generally beginning to make their presence felt on this fringe of the Greek world.

![]()

53

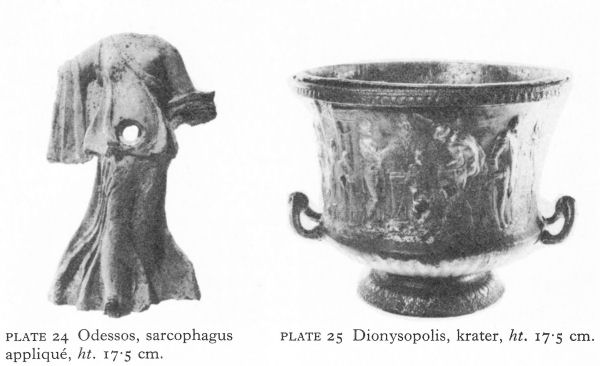

Plate 24 Odessos, sarcophagus appliqué, ht. 17.5 cm.

Plate 25 Dionysopolis, krater, ht. 17.5 cm.

In 179 b.c. the Bastarnae passed through, and Odessos was an early victim of Burebista’s Daco-Getic invasion of the mid-first century. Odessos, like Mesambria, had adapted to the commercial decline of Athens and to local changes. Under the threat of Burebista, links with the resurgent Odrysian vassal kingdom of the Romans grew stronger. Although this lacked stability, it was a trading area and also a refuge for at least a few Odessitans during the Daco-Getic invasion: soon after Burebista’s death, a decree acknowledged the protection given by one Sadalas. [25] Certainly not the Sadalas of the Mesambrian inscription, this one also is not clearly identified.

Funerary innovations typical of the Macedonian or Early Hellenistic era include barrel-vaulted Macedonian-type ashlar chamber tombs. Five have been identified in the vicinity of Odessos. One was found in 1932 beneath a large tumulus on which a memorial was being erected to commemorate the Polish prince ‘Ladislas of Varna’, who died here in battle against the invading Turks in 1444. The fourth-century b.c. tomb was conserved as part of the memorial to the fifteenth-century warrior prince. Its entrance had been destroyed and the contents looted in the distant past. A vaulted dromos, or passage, led into a square tomb chamber built of carefully dressed dry-stone blocks. In a similar tomb a wooden coffin had been decorated with terracotta appliqués of satyrs and maenads, like the one illustrated in Pl. 24.

A Thracian tumulus cremation near Galata contained a quantity of gold jewellery, including two finger rings, each with a woman’s head in relief on the gold bezel, considered to be imported Greek work of the fourth or third century. The mound itself, one of six in the necropolis, contained numerous sherds of black-glaze ceramic. More evidence of Greek influence in the Hellenistic period came from another tumulus burial by the Dionysopolis road. This mound, 25 metres in diameter, was one of the earliest excavated by the Škorpil brothers. In it was the skeleton of a woman wearing gold earrings composed of twisted, tapering hoops with lion-head finials,

![]()

54

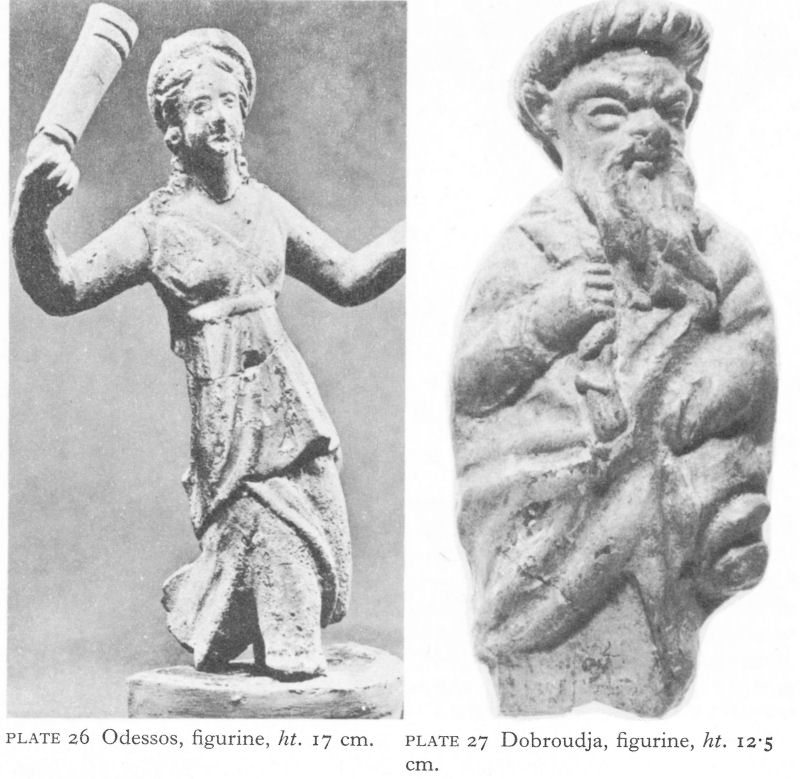

Plate 26 Odessos, figurine, ht. 17 cm.

Plate 27 Dobroudja, figurine, ht. 12.5 cm.

a Hellenistic type which gained widespread popularity in Bulgaria in the fourth century; other examples were found at Mezek (p. 73) and Seuthopolis. A bronze obol for Charon lay in the dead woman’s mouth.

At Dionysopolis itself, in a badly damaged ashlar tomb with two marble biers, a bronze krater, used for burning aromatic substances, was found by one of the skeletons. A ring encircling the top of the krater supported a dish-shaped sieve. The decoration, hammered in relief from a mould and well executed in the crowded Hellenistic manner, consists chiefly of scenes from Euripides’ tragedy Iphigeneia in Tauris (Pl. 25). The krater is attributed to the fourth or third century, the tomb itself being later. However, comparison with the silver ‘Chryses’ kantharos in the British Museum and with fragments of a marble krater from Mahdia in the National Museum, Bardo, [26] suggests that an early second-century date may be more likely.

Third-century imports included bone plaques decorated with figures finely incised with a sharp point. They were used to decorate coffins that in shape, if one may judge from the examples found on the Taman peninsula, imitated ornate stone sarcophagi and probably came from Asia Minor.

![]()

55

Of four such plaques found in the Galata burial containing the gold finger rings, two depicted women’s heads and two Dionysiac scenes. The material shows traces of paint. Ivory panels, decorated in much the same way, were found in the Great Bliznitsa and Kul Oba burials of the Taman and the Crimea, although here attributed to the fourth century. [27]