PART TWO. The Roman Presence

I. Ratiaria and the north-west 111

(Ratiaria; Bononia; Castra Martis; Montana)

II. Oescus and its vicinity 116

III. Nikopol 126

IV. Novae 128

V. Iatrus 133

VI. Transmarisca 135

VII. Durostorum 135

I. Nicopolis-ad-Istrum and the central slopes 143

(Nicopolis-ad-Istrum; Hotnitsa; Butovo; Discoduratera; Prisovo)

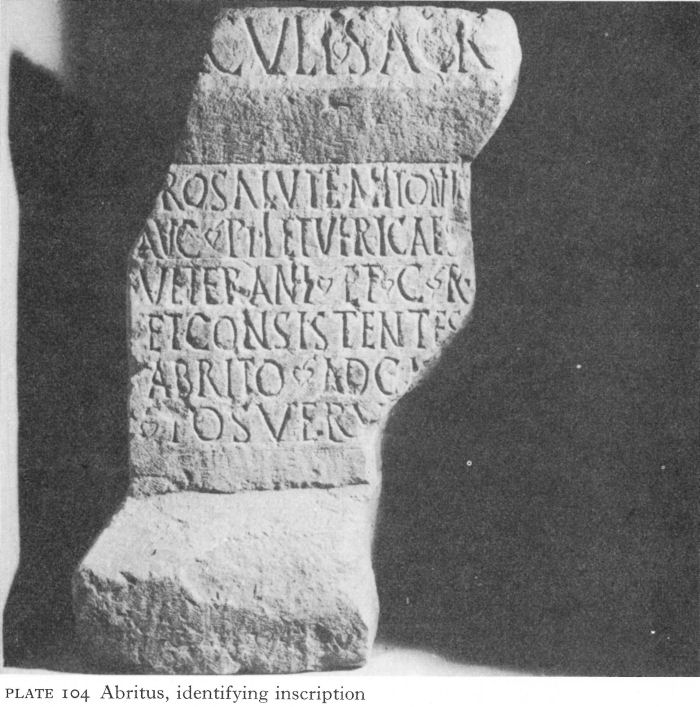

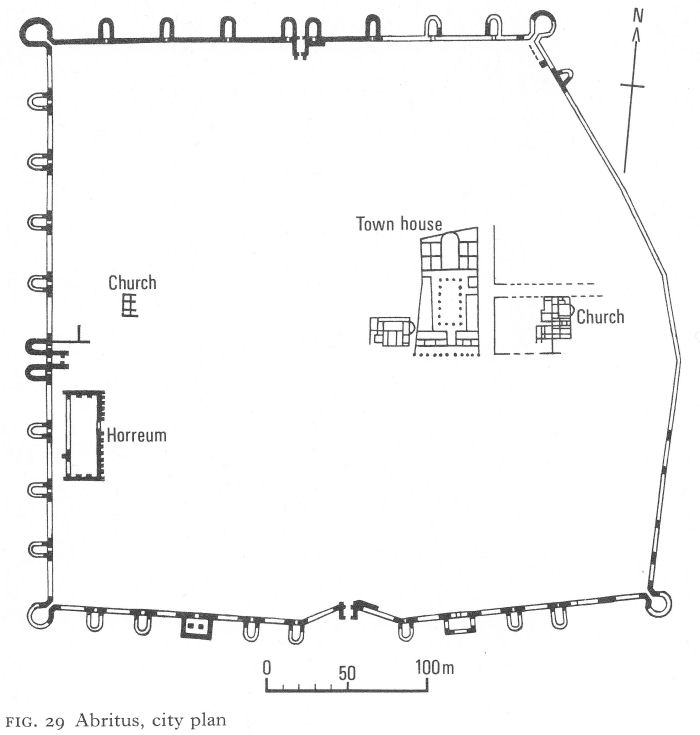

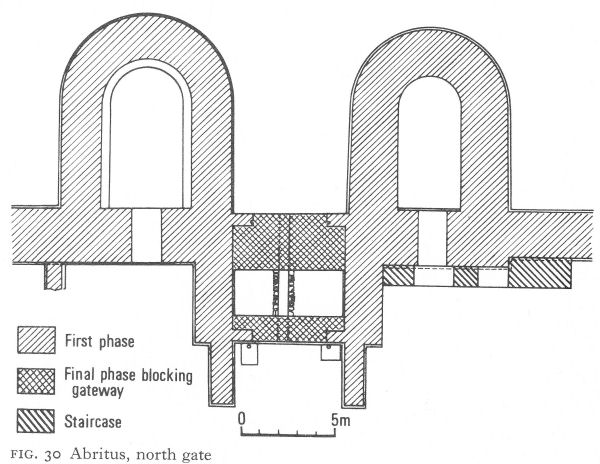

III. Abritus 156

IV. Voivoda 165

V. Madara 167

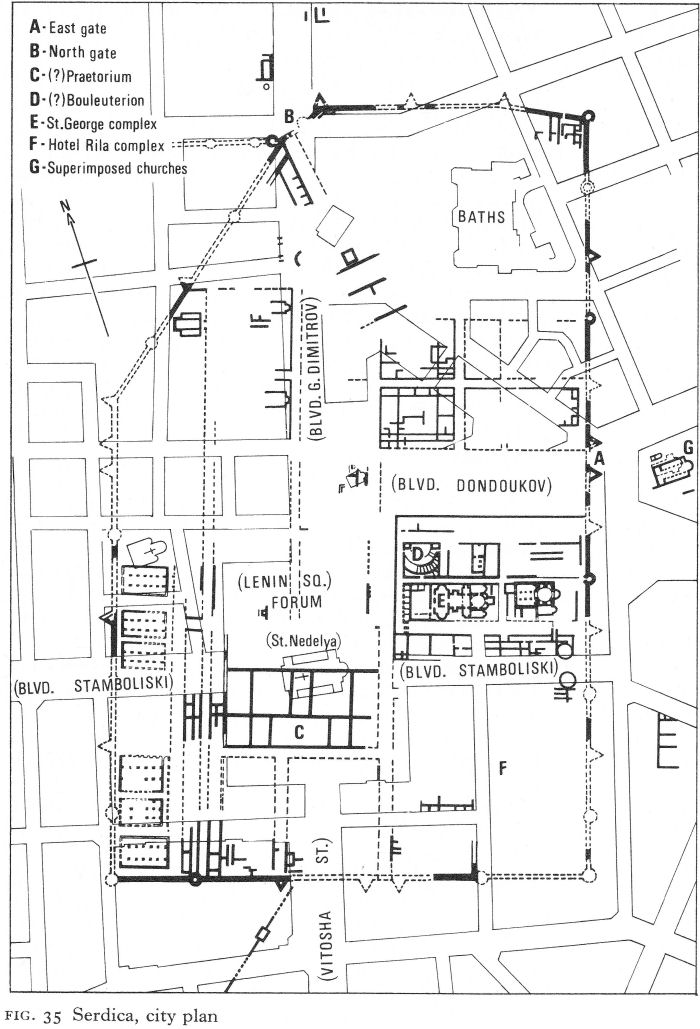

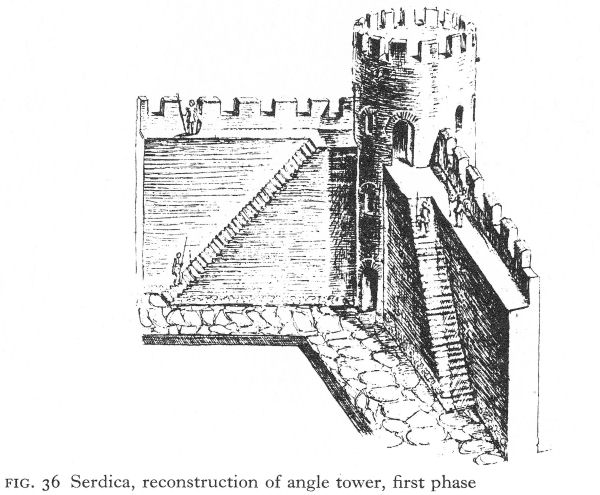

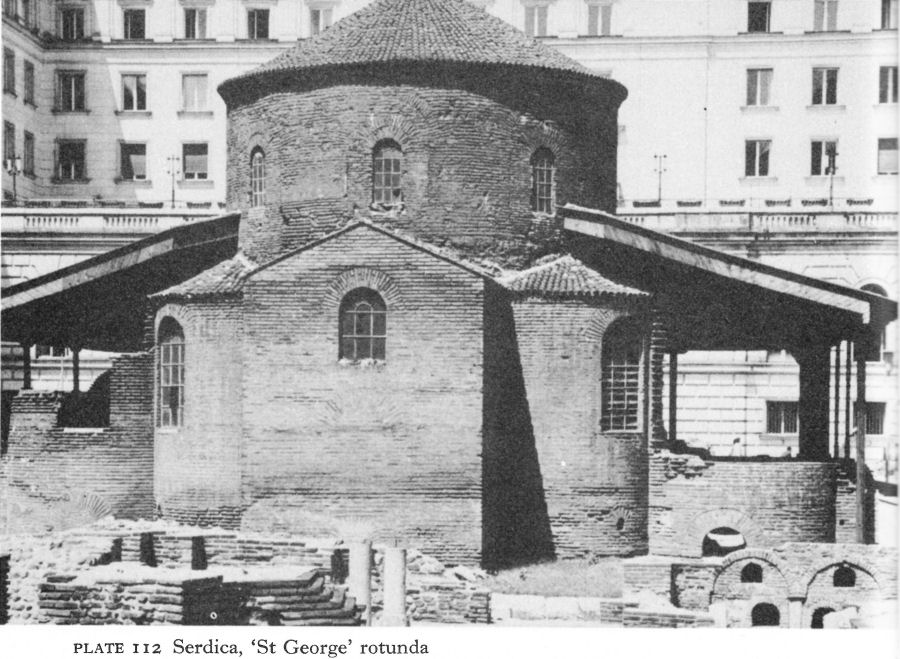

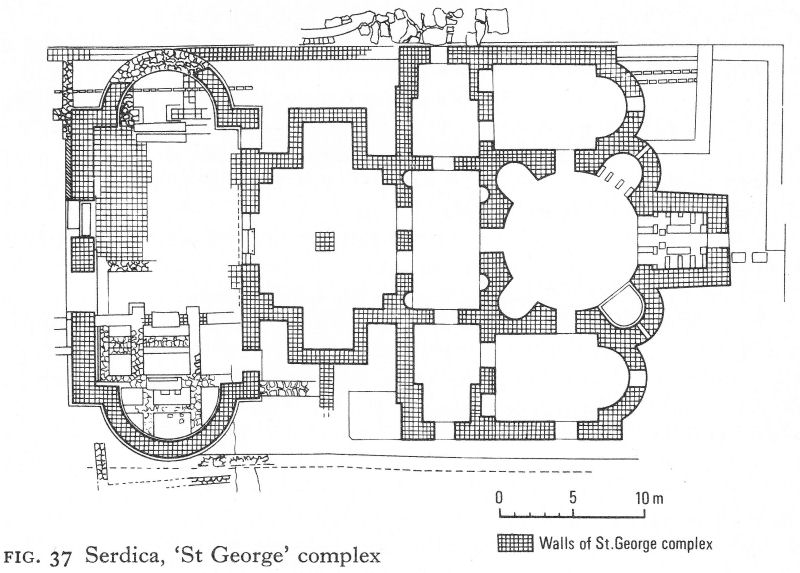

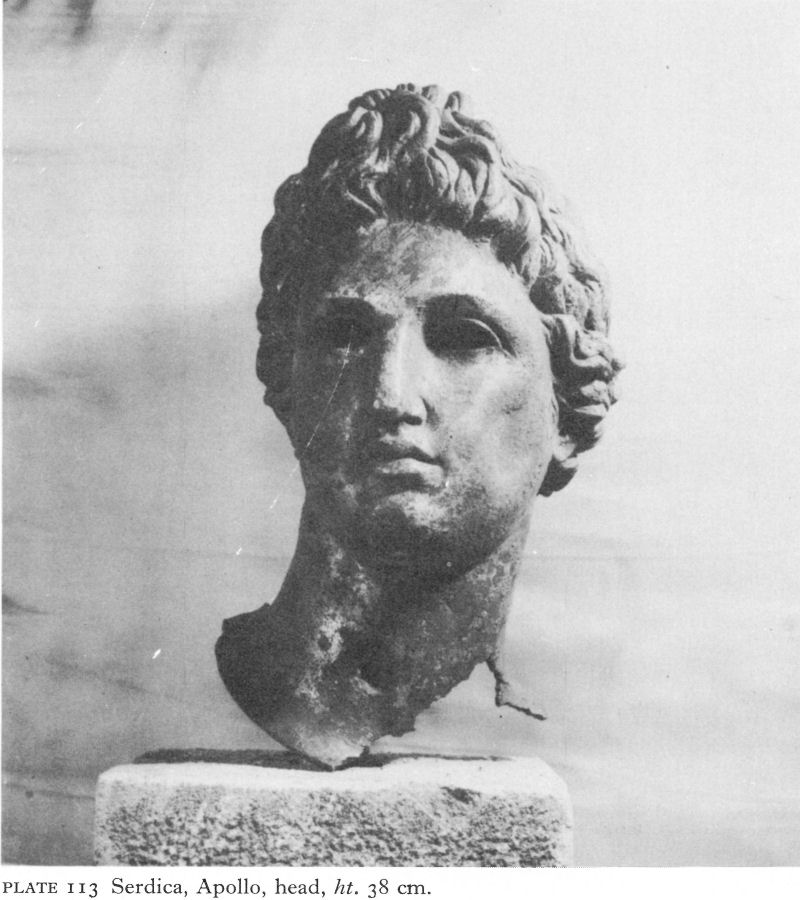

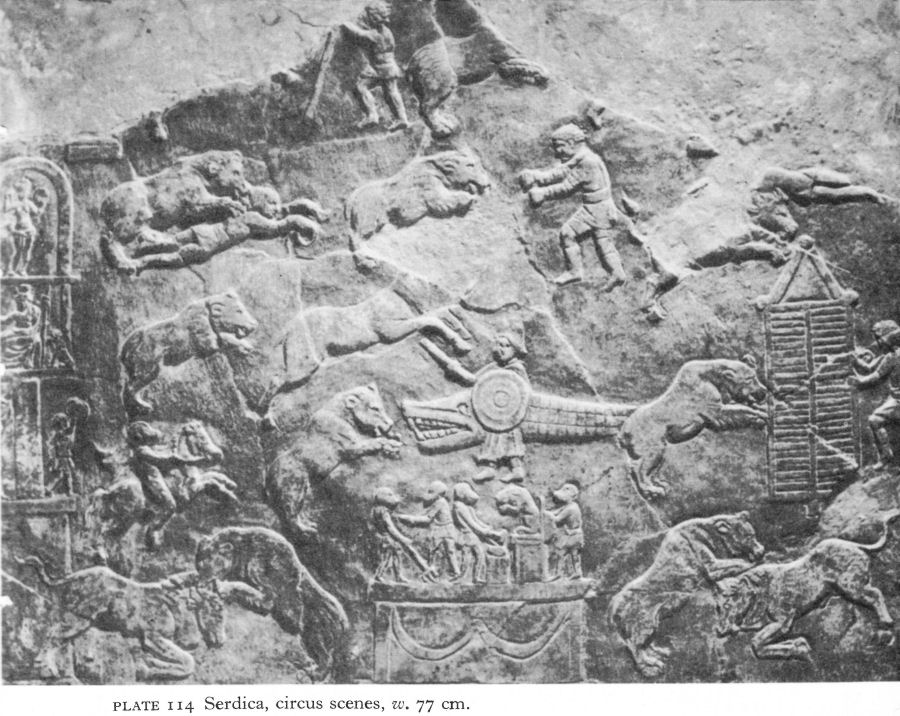

I. Serdica and its territory 169

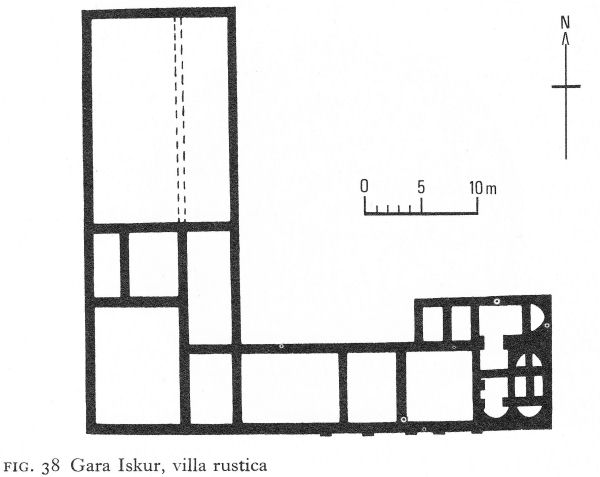

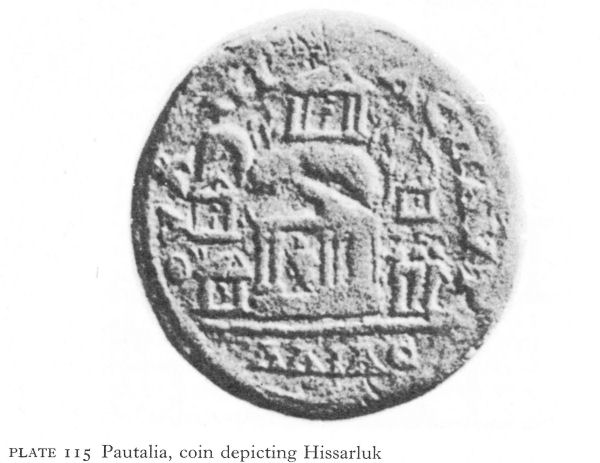

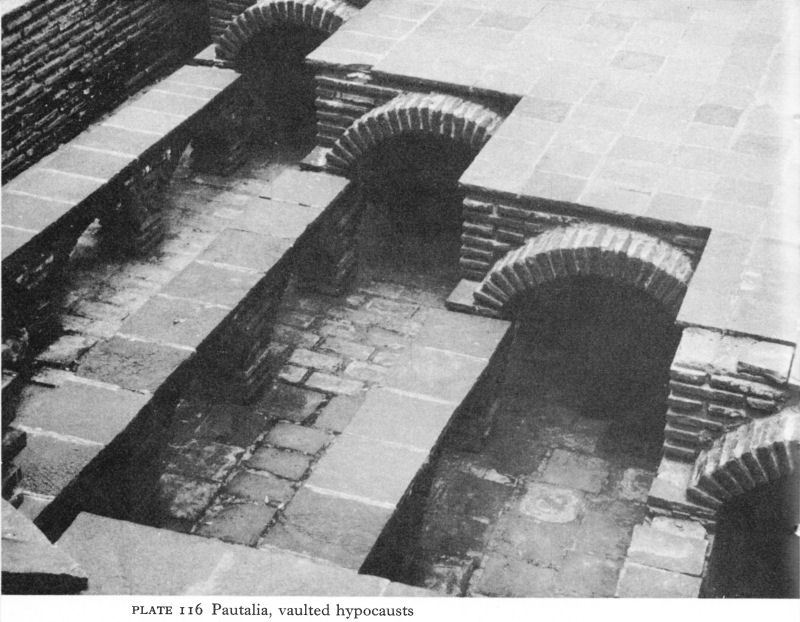

II. Pautalia and its territory 178

(Pautalia; The territory of Pautalia)

III. Sandanski 183

IV. The upper Mesta valley 185

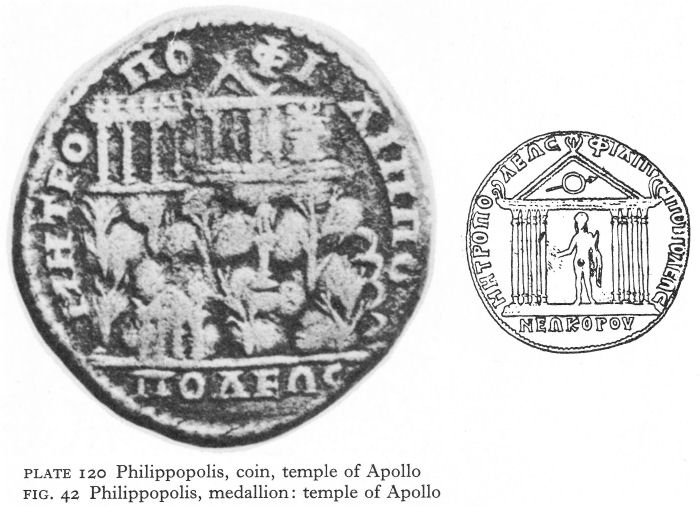

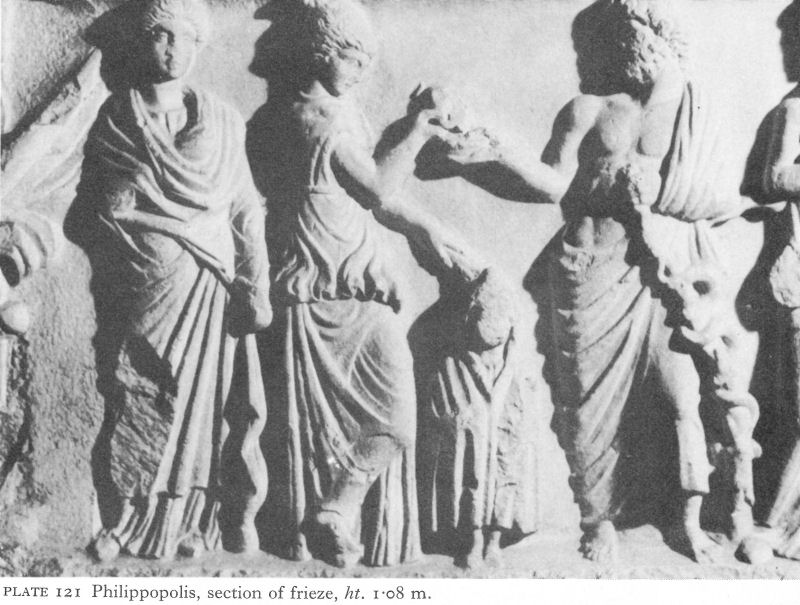

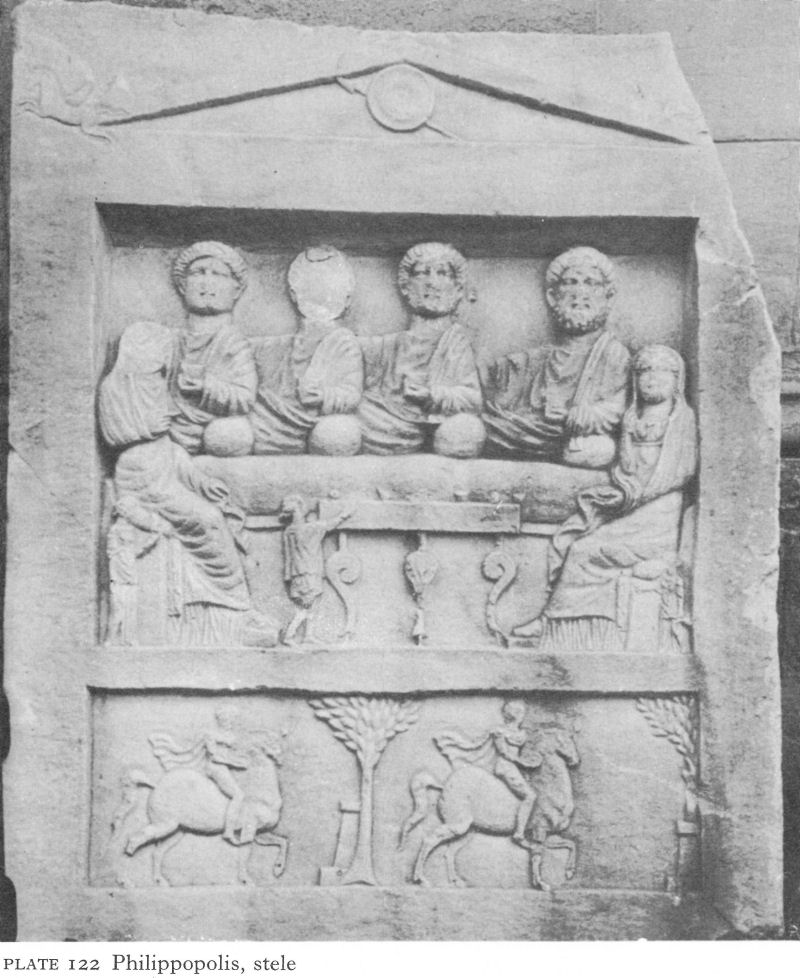

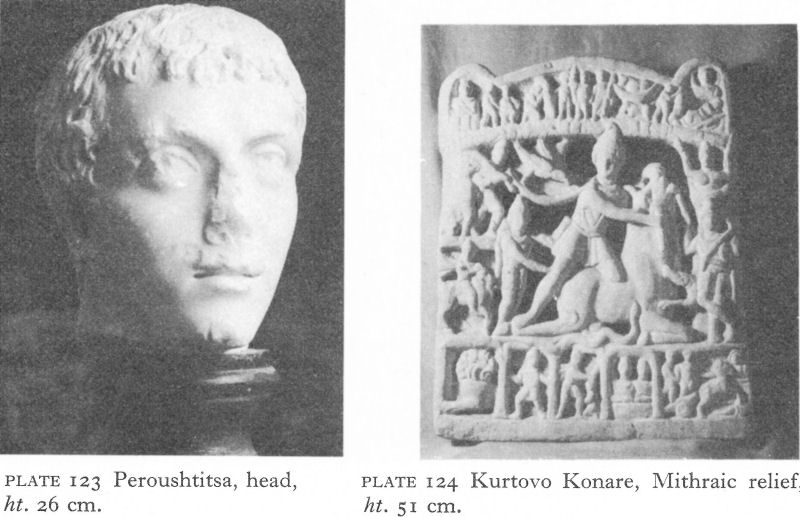

I. Philippopolis and its vicinity 187

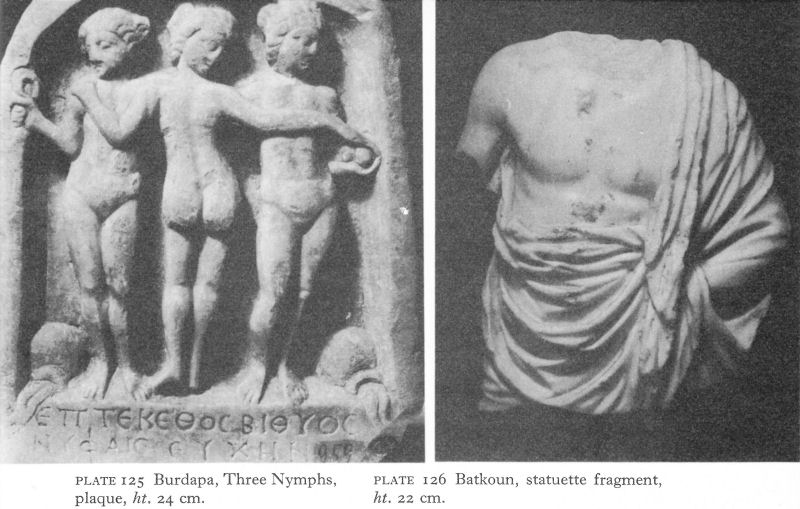

(Philippopolis; Peroushtitsa and Kurtovo Konare; Burdapa and Batkoun)

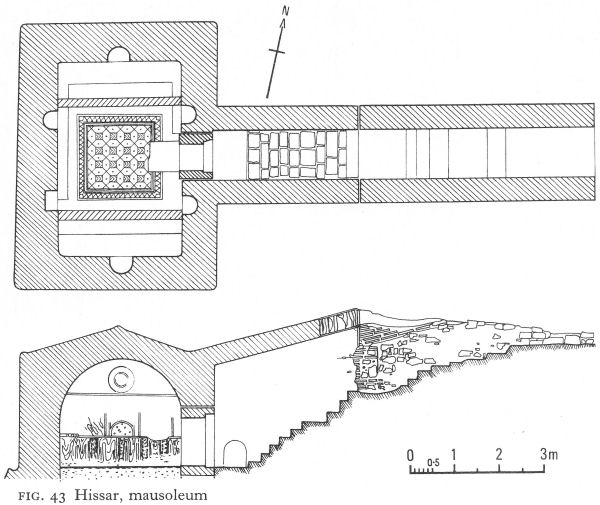

II. Hissar 197

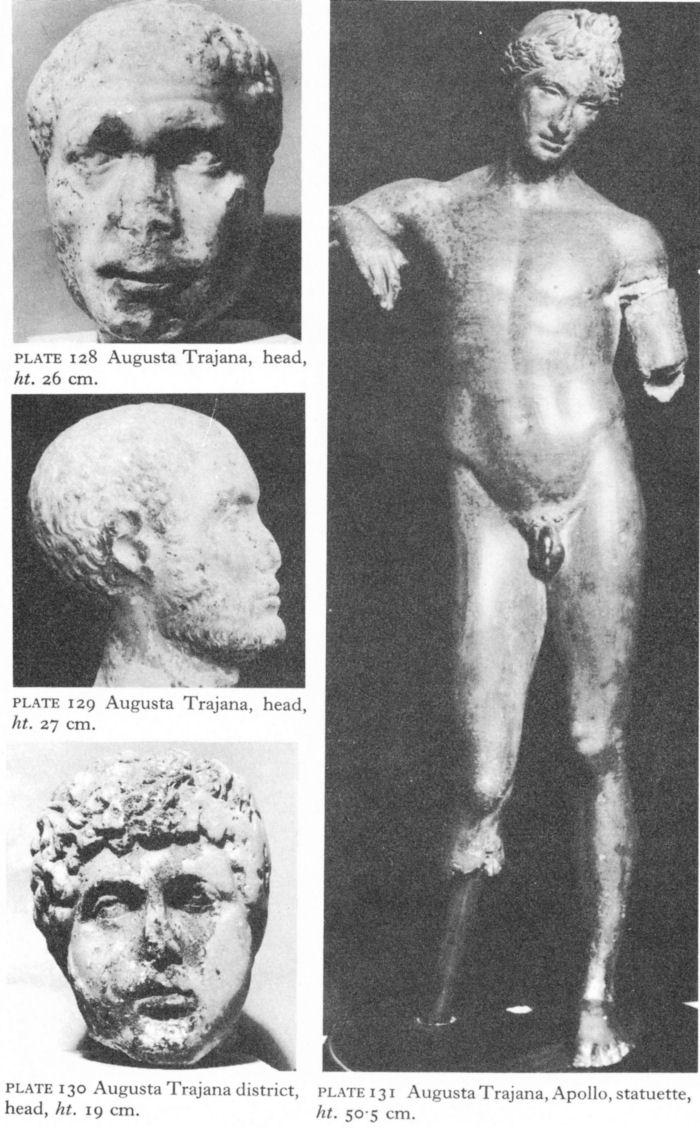

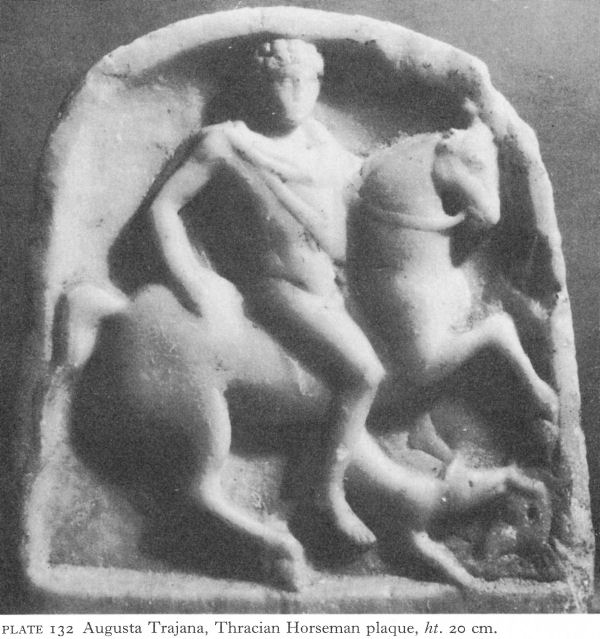

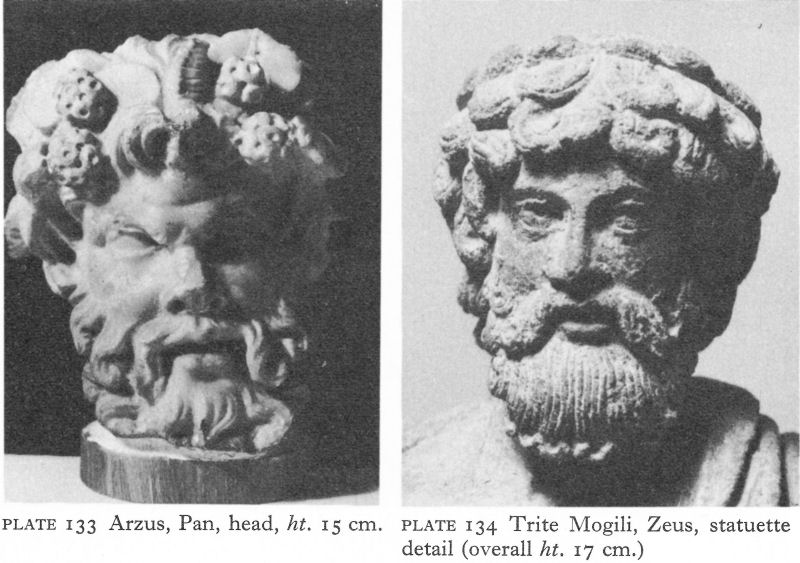

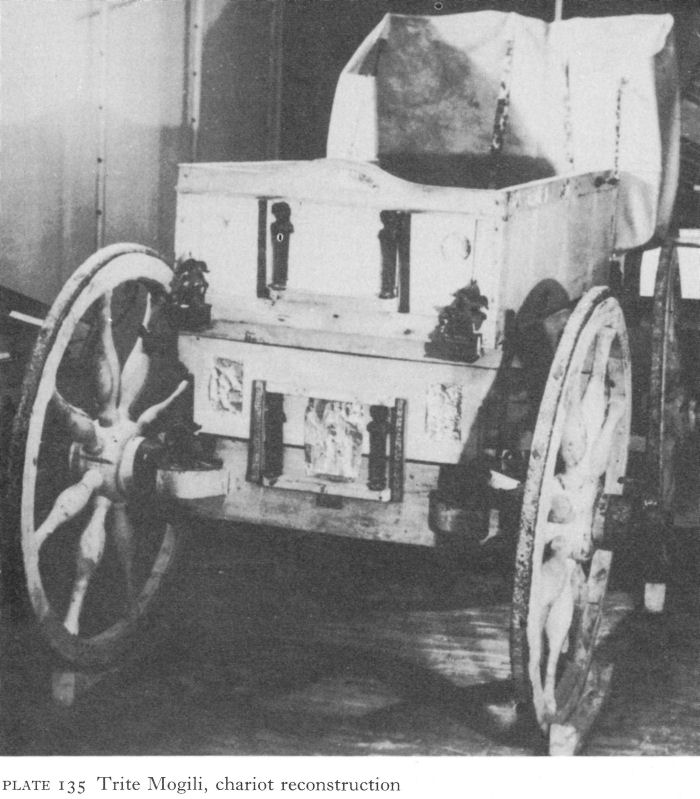

III. Beroe-Augusta Trajana and its vicinity 199

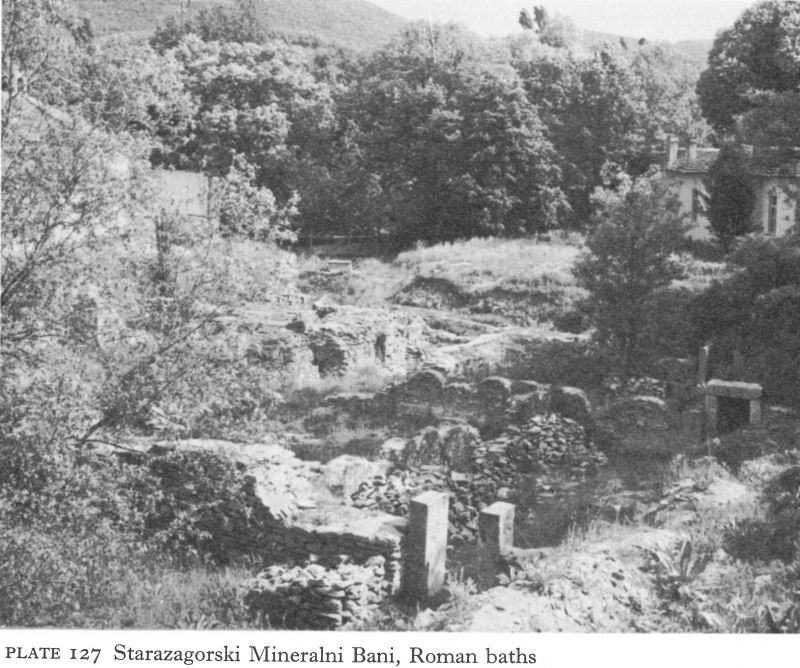

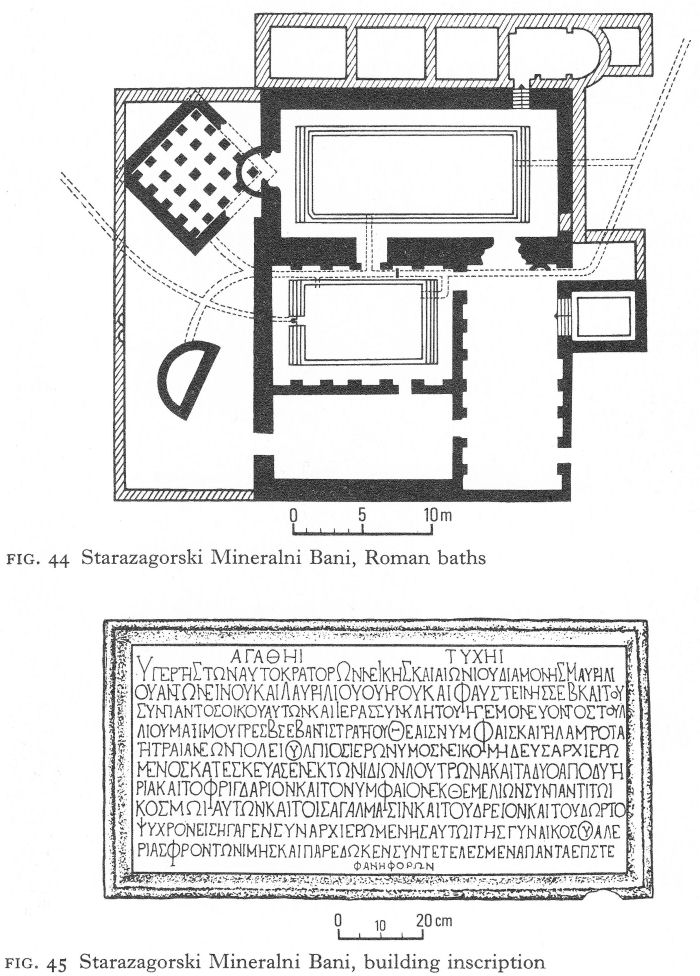

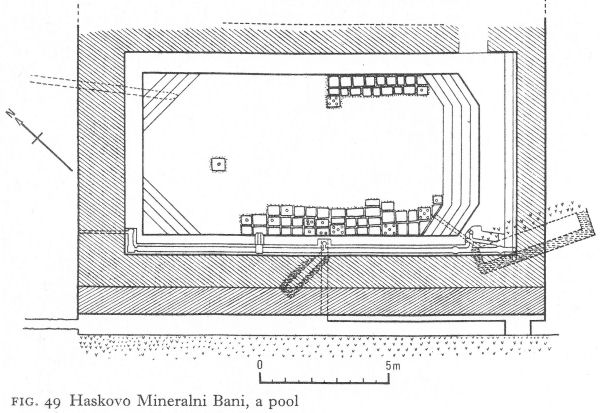

(Beroe-Augusta Trajana; Starazagorski Mineralni Bani; Arzus and Pizus; Trite Mogili, Mogilovo, and Krun)

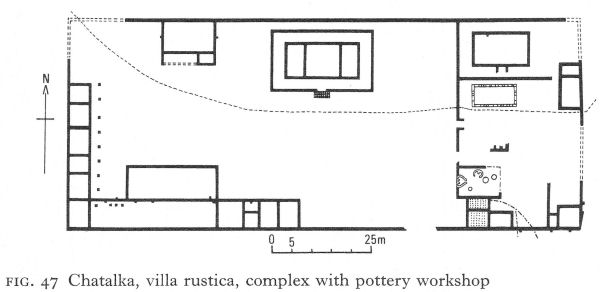

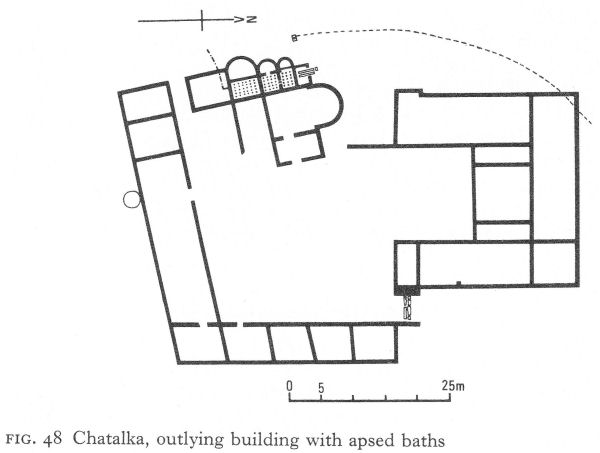

IV. Chatalka 209

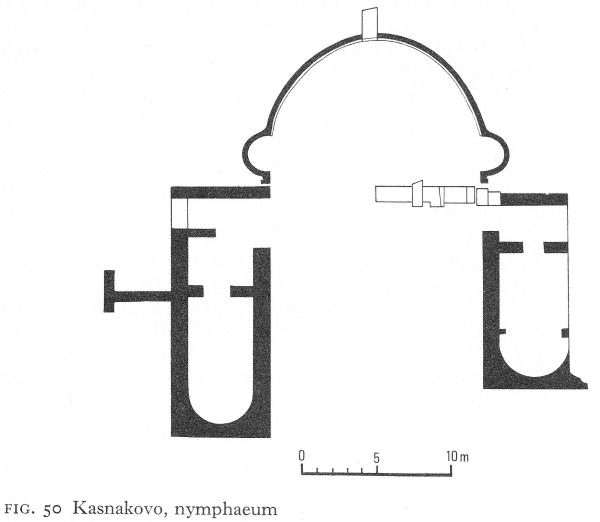

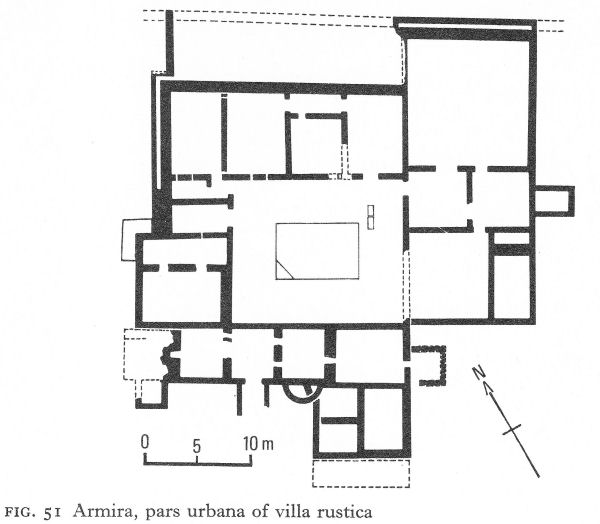

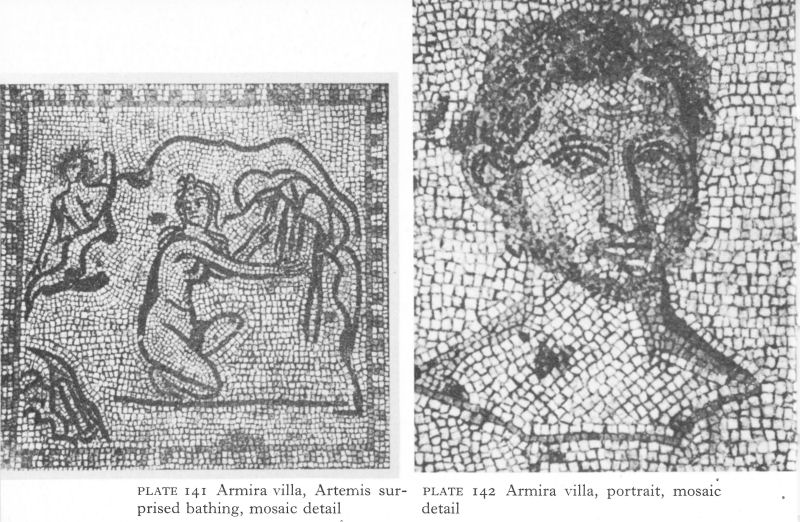

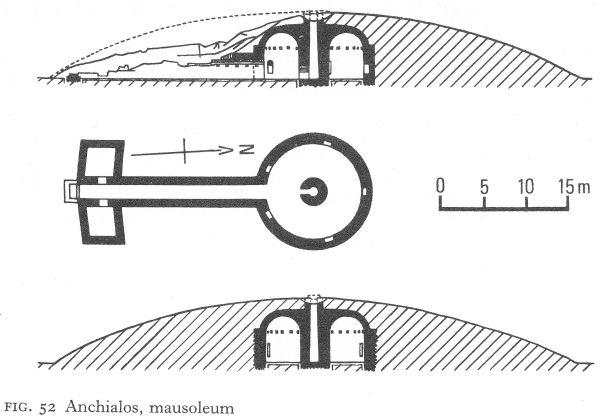

(Haskovo Mineralni Bani; Sveti Duh; Kasnakovo; Armira)

5. The Danube

I. RATIARIA AND THE NORTH-WEST

The establishment of permanent Roman camps along the Danube, extending from Pannonia into, first, what is now north-west Bulgaria and gradually reaching to the Black Sea coast, arose from the need to set up a viable line of defence against the Daco-Getic threat to Macedonia. While a measure of control had been attained over the Thracian tribes south of the Danube, those north of it - in present-day Romania - remained aggressively independent under the military leadership and influence of the Dacians based in the mountainous regions of southern Transylvania. Thus, instead of to the partially Hellenised interior, it was to the lesser-known north-west and south banks of the Danube that Roman organisation was first introduced and followed by a policy of Romanisation to replace the existing Thracian structure.

Ratiaria

Ratiaria (Archar), one of the oldest and to become one of the wealthiest Roman cities on the lower Danube (Pl. 1), was described by Dio Cassius as strongly fortified when Crassus campaigned against the Triballi and other Moesian tribes in 29 b.c. It grew rapidly in the first century a.d. and received the title of Colonia Ulpia Trajana following the conquest of Dacia. Predominantly although by no means exclusively settled by Romans and others of Italic descent - civilians as well as soldiers - the city was the focal point for the Romanisation of the surrounding territory. The name is generally considered of Latin origin and survives to some degree in that of the modern village of Archar.

Ratiaria’s commercial potentialities, as inscriptions show, also drew traders from Asia Minor. Besides serving as a port and point of transhipment enabling Danubian traffic to avoid the dangerous ‘Iron Gates’, it was the northern terminus of the shortest land route from Lissus (Lesh) on the Adriatic, and hence from Italy, to the lower Danube. In addition to its garrison, Ratiaria was a headquarters of the Danube fleet, at least from the time of Aurelian, who made it the chief city of the new province of Dacia Ripensis after the evacuation of trans-Danubian Dacia. Among its industries was one of the five imperial munition factories in the Balkan peninsula.

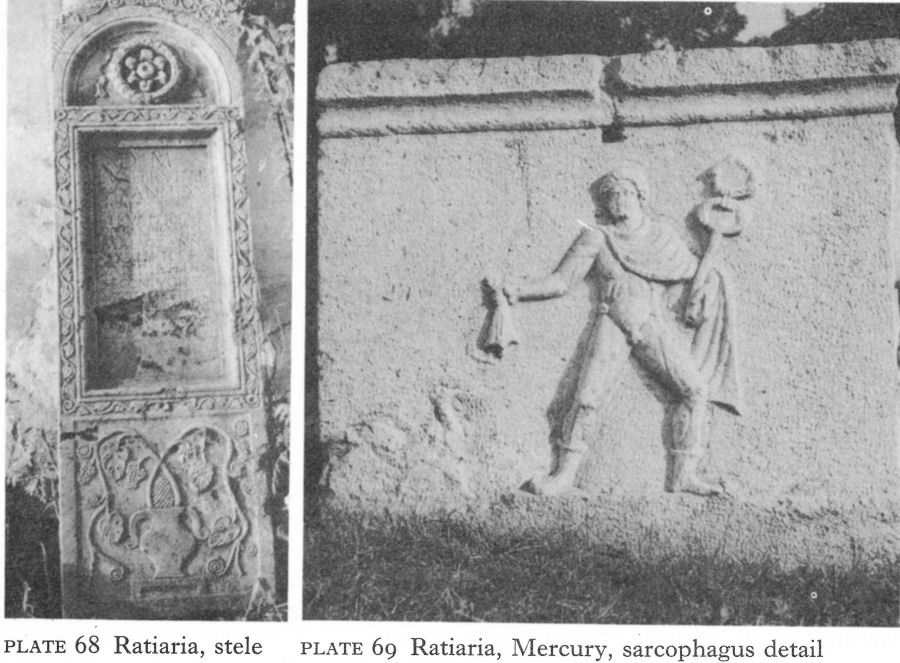

Today the site, on either side of the little Archar river, is covered by fields and vineyards, the village of the same name, and, on a low hill, the hamlet of Turska Mahala, where the citadel probably stood. Excavations undertaken within the last 20 years or so are reported to have located a necropolis, an aqueduct, and the beginning of the road to Bononia (Vidin), and to have shown that the city expanded westward after becoming a provincial capital, but the work has not yet reached publication stage. Surface finds have yielded many inscriptions and other objects. Essentially Roman and typical of many found along the Danube in its shape and carefully carved formal decoration of ivy and vine is a mid-second-century stele erected by a lady of probable Greek origin in memory of her Roman husband and her ‘dulcissima’ and ‘pientissima’ 18-year-old daughter [1] (Pl. 68).

111

![]()

![]()

112

Plate 68 Ratiaria, stele

Plate 69 Ratiaria, Mercury, sarcophagus detail

Other funerary intrusions into this land of tumulus burials are the locally carved sarcophagi. One - also of the Antonine period - has on one short side a relief of Hermes-Mercury, here no doubt intended as the herald of the dead but also suggestive of the commercial acumen and statecraft of Ratiaria (Pl. 69). Yet on two other approximately contemporary sarcophagi, both very alike, a small framed uninscribed relief of the Thracian Horseman appears as the centrepiece of otherwise elaborate conventional ornamentation, an illustration of the headway made even here by this Thracian cult in the second century.

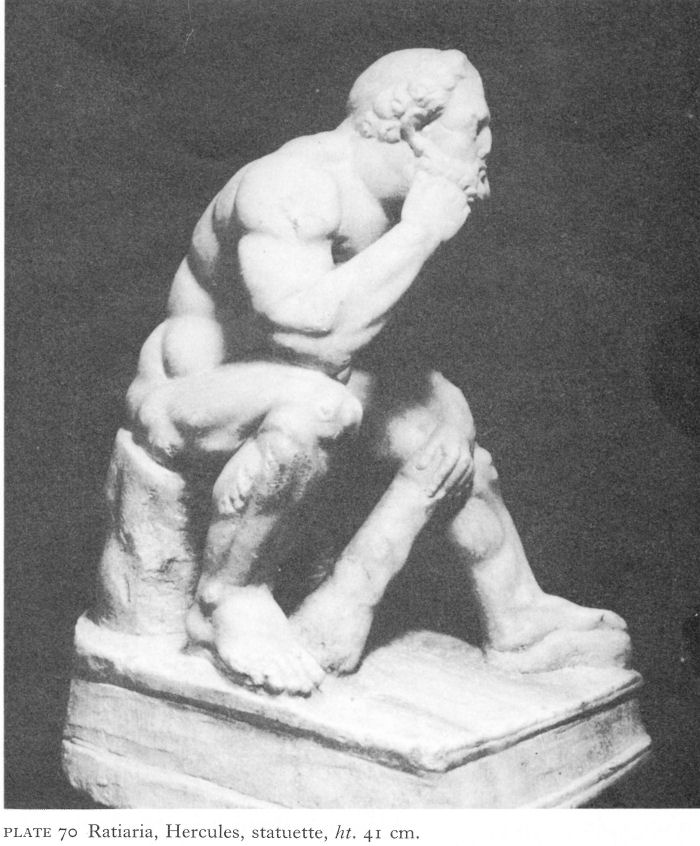

A dedication to Porobonus, a god of Celtic origin, has also been discovered, one of only three known in east Europe, the others at Abritus (Razgrad) and Olbia in south Russia. Worship of the Roman pantheon is naturally well represented, notably of Jupiter and Juno - portrayed together in a chariot on one relief - Pluto, Proserpina, Ceres, and Hercules. Mithras is a prominent secondthird-century addition. An unusual marble statuette of Hercules was found recently by an Archar farmer when building a pigsty. The muscular but pensive hero is seated, his chin resting against his right hand, his club dangling against his left knee (Pl. 70), a fascinating, coincidental mid-second-century intermediary between the ‘Thinker’ statuette of the Neolithic Hamangia culture of the Dobroudja and Rodin’s Penseur.

Bononia

About 10 kilometres upstream from Ratiaria and within its territory was Bononia (Vidin), a station of secondary importance during the Roman period.

![]()

113

The name is equivalent to Bologna and Boulogne and the site may have been a Celtic settlement before the Roman arrival, when a cavalry detachment was stationed here. Bononia’s remains now lie below a busy modern town and the medieval and Turkish fortress of Baba Vida on the bank of the Danube. In the latter area soundings have uncovered fortifications of the second half of the third century, when the evacuation of Dacia must have increased its military importance. The best-preserved part was a polygonal north-east angle tower, a powerful structure enclosing an area 13 metres across, of which walls up to 2 metres high and nearly 3 1/2 metres thick were found. A public bath with its heating system and a drainage network carrying waste into the Danube, dating from about the same period, have also been identified.

Plate 70 Ratiaria, Hercules, statuette, ht. 41 cm.

![]()

114

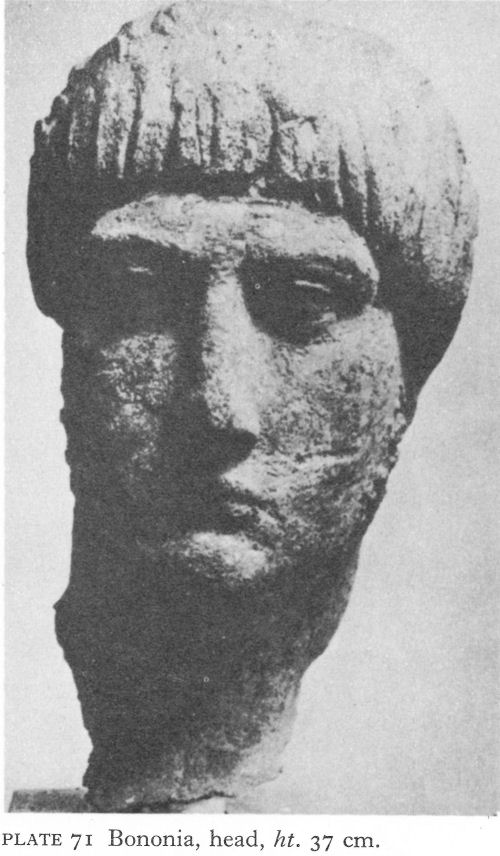

Plate 71 Bononia, head, ht. 37 cm.

A recent chance find near the fortress was the fine bronze head of a young man, stylistically associated with the reign of Trajan (Pl. 71). Such work is likely to have come from or through Ratiaria.

Castra Martis

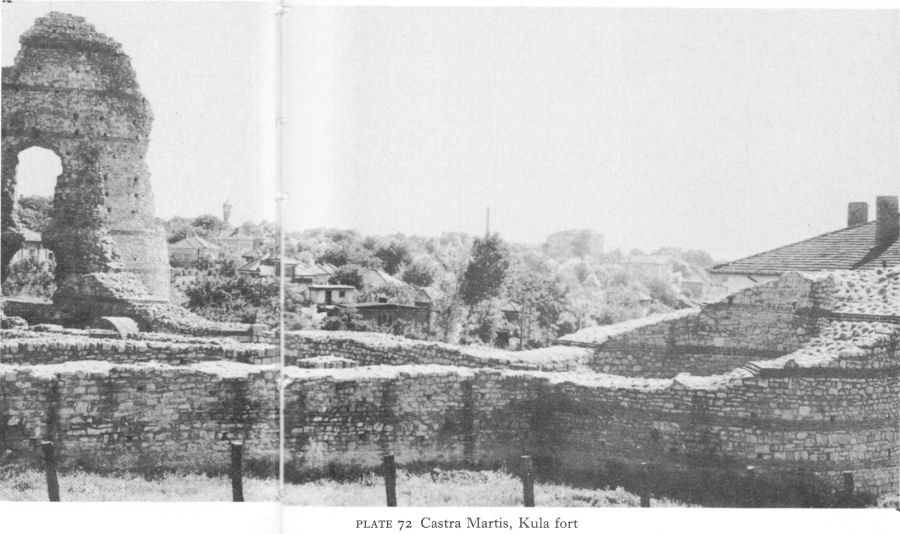

A station on the road leading west from Ratiaria to Naissus (Niš) and the Adriatic has been identified some 24 kilometres south-west of Vidin. This is Castra Martis (Kula), where a short sector of wall has been uncovered. In the main square of the little town are substantial remains of a small square fort - its sides 34 metres long - built to protect the north-east angle of Castra Martis. One of the four round angle towers - still, with later repairs, 16 metres high - has given the town its Bulgarian name, ’kula’ meaning ‘tower’. The three other towers, walls and inner buildings including the garrison commander’s quarters, barracks, and a craft workshop have been excavated (Pl. 72), and the structure dated to the late third or early fourth century. Unlike the walls which, so far as one can tell, were of stone only, the towers were of roughly dressed stone,

![]()

115

Plate 72 Castra Martis, Kula fort

bonded with irregularly spaced layers of three brick courses. The single entrance, flanked by guardrooms, was in the south wall.

Montana

Excavation - halted by the First World War and only resumed in 1968 - is now uncovering the most renowned Roman sanctuary in this corner of Bulgaria, the temple of Diana and Apollo at Montana (Mihailovgrad, formerly Ferdinand). By 161-63, if not before, Montana, situated where the Marcianopolis (Reka Devnya)-Nicopolis-ad-Istrum (near Nikyup)-Melta (Lovech) road bridged the Ogosta on its way to join the Ratiaria-Naissus highway, had achieved the status of Municipium Montanensis. Fortifications, including a great U-shaped angle tower measuring 24 by 18 metres, were, it seems, constructed about the middle of the third century and lasted until the late fifth or early sixth.

The temple of Diana and Apollo, on the evidence of many Latin inscriptions, was already in existence in the second century and occupied the site of an earlier Thracian sanctuary - a great spring at the foot of the rocky hill on which the fortress stood. It is believed to have survived destruction until the fifth century.

![]()

116

The 1915 excavations uncovered a niche hollowed out of the cliff by the spring, intended for a statue of Diana. An altar dedicated to her stood in front of it; nearby was another to Silvanus. Three statuettes of the goddess were found among the ruins as well as broken pieces of others of Silvanus, Apollo, Hygieia, and a Thracian Horseman relief with part of a Greek inscription - a rarity in Montana where Latin was commonly used. Many fragments of altars and votive tablets to Greco-Roman deities, mostly Diana and Apollo, were used as building material in the town. Worship of the huntress goddess seems to have been especially widespread in this region; another sanctuary is known to have existed at Almus (Lom). In view of the Thracian origins of the sanctuary, the find of a Thracian Horseman relief almost certainly reflects syncretism with Apollo, just as Bendis with Diana-Artemis. With such continuity in the ancient world, it is hardly surprising that an altar consecrated to Diana and Apollo was discovered beneath the altar table of a Mihailovgrad church.

Other cult objects from Montana include a find of 11 small clay plaques depicting religious motifs or gods, usually framed in aediculae, or pillared niches [2]. The superficial resemblance to the Abritus collection of bronze plaques (pp. 164 ff) is very striking, but the Montana group are much cruder and entirely devoid of oriental influences. Exceptions to the normal pantheon here are Epona standing between two foals - a Celtic influence possibly connected with the Cohors II Gallorum stationed in the province under Trajan - and a Thracian Horseman.

II. OESCUS AND ITS VICINITY

Oescus

Oescus (near Gigen) shared with Novae (near Svishtov) the main burden of defending the central region of the lower Danube. Established in the early years of the first century a.d. as the headquarters of Legio V Macedonica, it replaced an earlier Triballi settlement; Ptolemaeus refers to it as Oescus Triballorum. The site was a low plateau with steep slopes on the north and north-west, some 5 kilometres from the Danube and its confluence with the Iskur, the ancient Oescus. Like Ratiaria, it was an important centre of Romanisation and attracted a considerable civil population. Identified by Count Marsigli in the eighteenth century, Oescus was first excavated in 1905-6, the main purposes being apparently a search for works of art and the location of the forum. A large area was uncovered to little scientific purpose, no results being published and no records left. The ruins were then abandoned until 1941-43, when an Italian team excavated a large building outside the city walls. Excavations by Bulgarian archaeologists in 1947-52 and again more recently have thrown much new light on the antique city and it is encouraging to know that work is being continued.

The oldest stone fortifications probably belonged either to the end of the first century, after the Dacian invasions of 85-86, or to the beginning of the second, before the departure of Legio V Macedonica (of which the future emperor Hadrian was a tribune) in 106 as a result of the conquest of Dacia. Massive walls, some 3 metres thick but, except by the gate, apparently without bastions or towers, enclosed a roughly pentagonal area of about 18 hectares. A ditch about 15 metres wide gave added protection. The city expanded rapidly in spite of the loss of its military importance, but with the legion’s return on the evacuation of Dacia in 271-75, Oescus again became a major fortress of the limes.

![]()

117

The city had suffered severely at the hands of the Goths in the middle of the third century. The original wall was repaired and a new one built to enclose a further 10 hectares on the long east side. Faced on the outer side with well-cut stones, it was strengthened at intervals by horseshoe-shaped towers and, at the sharp north-east angle, by a round projecting one. Flanking towers protected the north and east gates. Temples as well as houses were demolished to make room for the wall, but many large buildings were left outside, as well as the dwellings of those without citizenship. The plan of the fortified area now resembled the end view of a gabled house, the ground floor of which was represented by the third-century addition.

Within the city there was the usual grid of intersecting north-south and eastwest streets. Paved with large stone slabs, some showing wheel-ruts, these were from 3 1/2 to 7 metres wide, the main ones being colonnaded. Beneath them ran water-supply and drainage systems, the former in clay and lead pipes. Wells provided a reserve, but the main water-supplies came by aqueducts, one 20 kilometres long. In a shorter aqueduct from a spring near Gigen, well-fired clay pipes were found, with tile-covered openings at intervals for cleaning and unblocking.

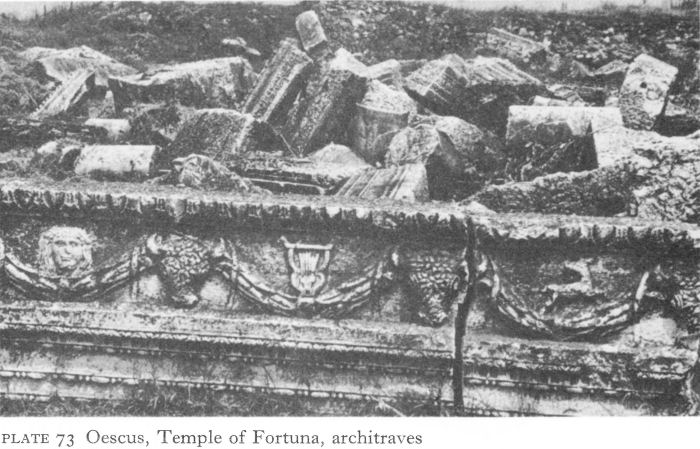

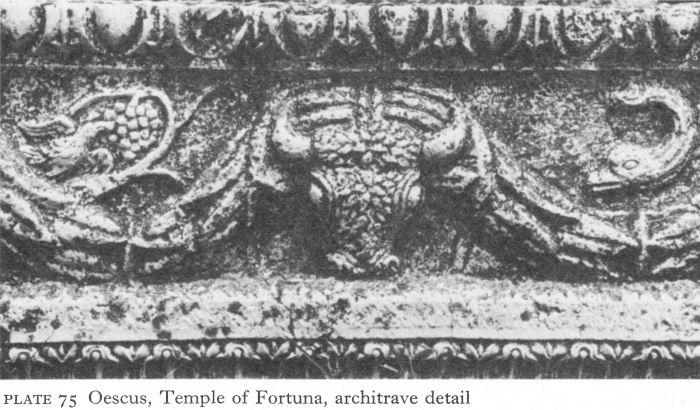

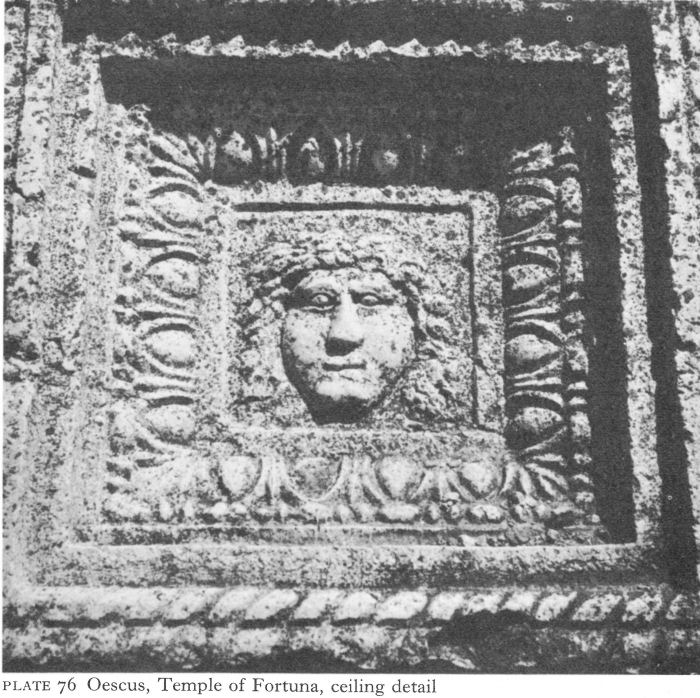

South of the probable location of the forum stood one of the city’s major buildings, the temple of Fortuna, a complex extending over an area 29 metres wide and some 50 metres long. The temple was entered from the south through a Corinthian-style portico bearing a long dedicatory inscription to the effect that the temple was erected by leading citizens in the reign of Commodus, whose name was chiselled out following his generally welcome assassination. The portico opened into a peristyled courtyard, also in Corinthian style, at the northern end of which stood the sanctuary. Along the sides of the temple, rooms with mosaic-paved floors are thought to have been used for commercial purposes by the guild who built it. [3] Destruction at the end of the fourth century, probably either by the Visigoths or by local Christians, was complete and it is likely that the present desolate scene of heaps of massive broken columns, bases, Ionic and Corinthian capitals, architraves, and battered fragments of pediment has changed little in 1,600 years - except for a space cleared to build a church in the twelfth century. The architraves from the colonnade - with their motifs of bucrania, garlands, masks, animals, dolphins, eagles, snakes, and the wine barrel, like other sculptures in the same area are the work of skilled and talented craftsmen (Pls. 73-75). Matching them is a panel of the coffered ceiling of the portico (Pl. 76).

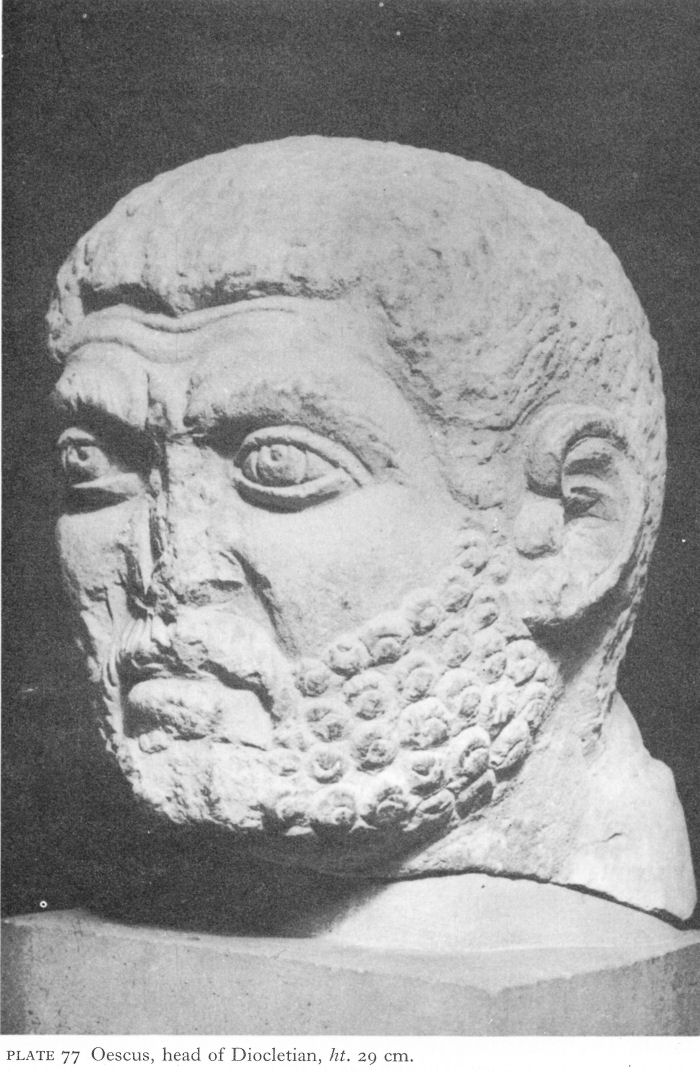

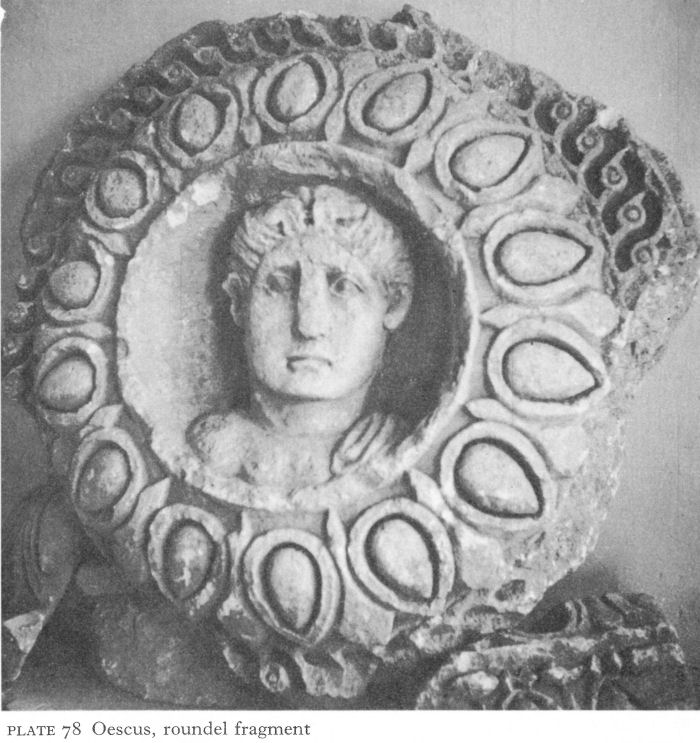

Sculpture appears to have continued to be a flourishing industry in Oescus until the disastrous Visigothic wars of the late fourth century. Among the more interesting finds in the neighbourhood is a fine sandstone head, found in a nearby village and probably looted from the city (Pl. 77). Stylistically dated to the end of the third century, it is believed to be a portrait of Diocletian. Others, within roundels, may be either architectural fragments or funerary reliefs (Pl. 78).

On the other side of the street, south of the temple of Fortuna, was an even larger structure; 72 metres long, it occupied a whole block or insula, and was reconstructed several times. The entrance was again from the south.

![]()

118

Plate 73 Oescus, Temple of Fortuna, architraves

Plate 74 Oescus, Temple of Fortuna, architrave detail

![]()

119

Plate 75 Oescus, Temple of Fortuna, architrave detail

Plate 76 Oescus, Temple of Fortuna, ceiling detail

![]()

120

Plate 77 Oescus, head of Diocletian, ht. 29 cm.

![]()

121

Plate 78 Oescus, roundel fragment

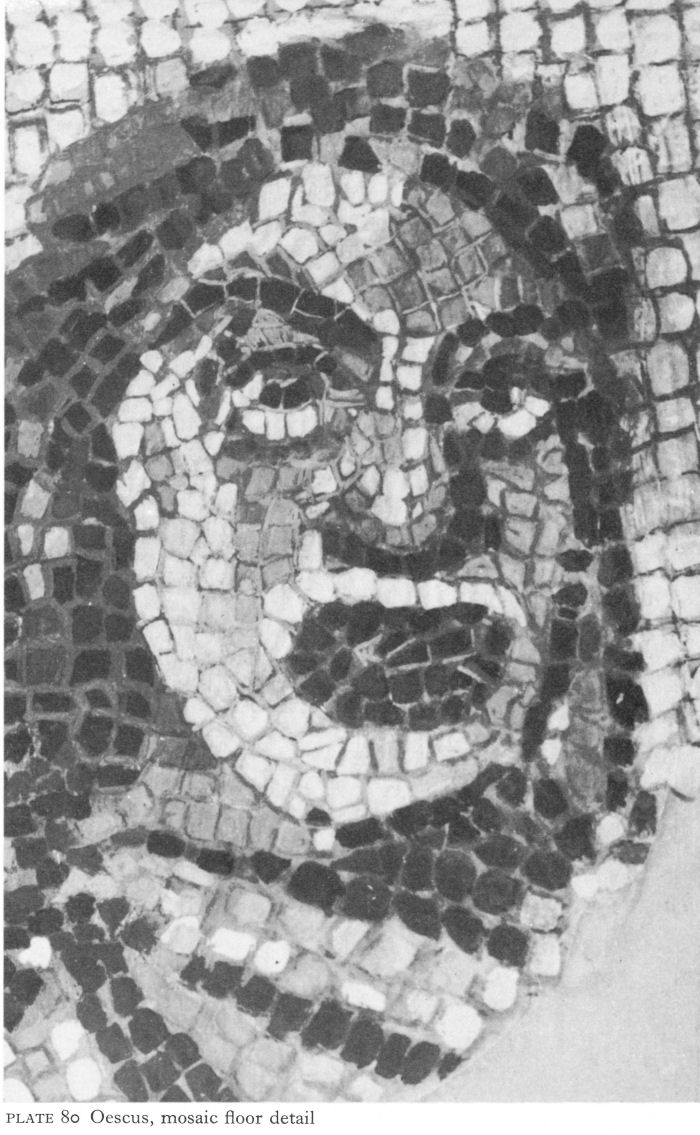

On the east side some 15 rooms were uncovered, most with hypocausts using pillae, or small brick piers. More heating came from warm air circulating between the walls and their marble revetment. An apsed room, 27 metres long and 12 metres wide, was a ceremonial hall. In a room near the entrance, 7.20 metres long by 6.60 wide, was a mosaic floor of literary as well as archaeological interest. A black and white chequered border frames a tripartite coloured picture, the two outer sections being narrow rectangles. On one side, two fighting cocks are separated by a formal garland and a tree; top and bottom are missing. The other side, showing different fishes in a river, is realistic and asymmetrical. The square middle section inscribes an octagon, with a boar, a lion, a bear, and a (now lost) bull in the corners, representing the seasons. In the octagon are four actors, three wearing comic masks. Part of the scene is lost, but above the heads a Greek inscription reads ‘Menander’s Achaians’ (Pls. 79, 80).

Menander is known to have written over a hundred comedies, but this find, probably dating to the first half of the third century a.d., added another, then unsuspected.

![]()

122

Plate 79 Oescus, mosaic floor detail

A since discovered papyrus [4] listing some titles of Menander’s plays has included ‘The Achaians or the Peloponnesians’, almost certainly the same play. T. Ivanov, who discovered the mosaic, suggests that the scene depicts the quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles, with Nestor attempting vainly to mediate and Patroklos, without a mask, standing behind; he relates it to scenes in the House of Aion at Antioch, also linked to comedies by Menander. This Trojan war interpretation has been queried, largely on the grounds that all the surviving comedies are based on contemporary - fourth-century b.c. - themes, not on mythological subjects, although this need not necessarily exclude a parody of Homeric heroes. The only Roman mosaic known in northern Bulgaria, its high, if provincial, quality confirms the impression created by the sculptured fragments of the prosperity and even luxury of Oescus.

To the east of this building were the public baths. Built in the second century by the then east wall, they were reconstructed after the extension of the city and covered an area of 700 square metres. The baths have not been published in detail, but it is known that they followed the common Roman pattern;

![]()

123

Plate 80 Oescus, mosaic floor detail

![]()

124

the floors and walls were revetted by slabs of white, grey, and pink marble. Across the road to the north was a row of shops.

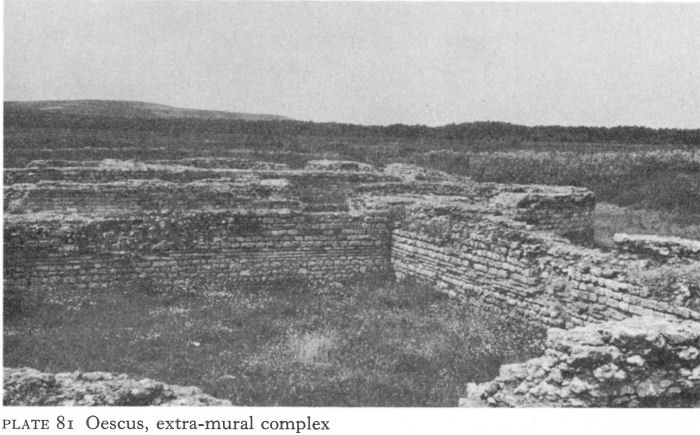

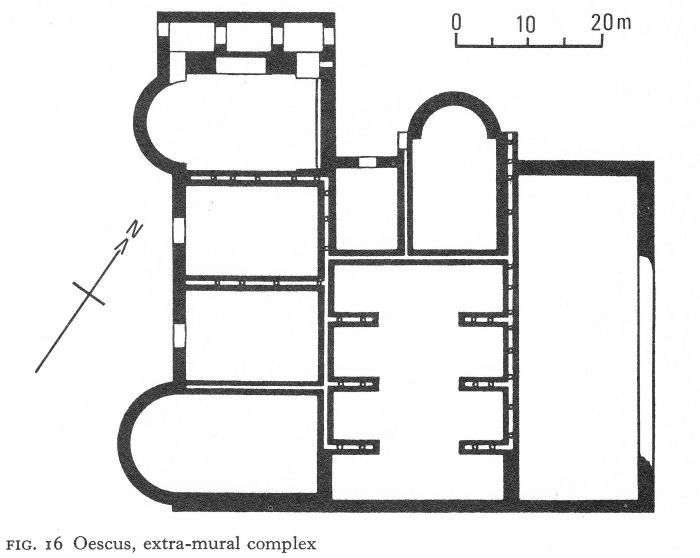

The 1941-43 excavations uncovered a large complex of unknown purpose occupying some 3,500 square metres outside the walls, immediately south of the original south-east corner (Fig. 16; Pl. 81). On the west side, two apsed rooms, one with three side-chambers, enclosed two rectangular ones. In the centre, a large hall was partitioned into four areas by three pairs of walls which projected from the long sides towards the centre. North of this hall were two other rooms, one apsed, and on the east side is a plain rectangular hall. Whilst the outside walls were solid structures, the foundations of the inner ones were threaded by a system of vaulted corridors, averaging a height of 1 1/2 metres and a width of half a metre, reached by a flight of six steps next to the northern apse. Along most of the internal walls, clay pipes, 15 centimetres in diameter, rose vertically at irregular intervals from the vaults of these corridors to penetrate the middle of the walls.

Such intra-mural corridors are not without parallel in Bulgaria, occurring, for instance, in the baths at Odessos and a building in Serdica (Sofia). Yet in Oescus, although the general plan is not inconsistent with that of a bath, one already existed and the siting of the various entrances makes this unlikely. Also, there were no hypocausts or other evidence of baths, although A. Frova writes that this might possibly be due to later destruction, particularly of the floors. The corridors could not have been parts of a drainage system as, in an already notably damp environment, they would merely have held water. The predominant use of stone, which does not conserve heat as well as brick, would have been unsuited to a heating system. Frova consequently concludes that the corridors were for ventilation.

It must have been an important building. The surviving walls consisted of three courses of brick between a lower section of roughly cut stones and upper layers of ashlar with a rubble filling. Marble revetment slabs of many different colours were imported, perhaps from as far afield as the Greek mainland, the Cyclades, and Egypt. Architectural fragments, including white marble cornices, Corinthian capitals, hexagonal and octagonal floor tiles, emphasised the luxury of this unusual building. On the evidence of coins and of structural comparisons, Frova dates it to the first half of the third century, that is to say before the first Gothic invasions.

Graves, mostly unpublished, were found in all directions round the city, the main cemetery being along the road to Novae (near Svishtov). Inhumation was the most common burial custom and the graves varied from the elaborately carved sarcophagi of the rich to interments straight into the earth. The Triballi in the territory of Oescus continued, like the Thracians elsewhere, to construct tumuli when they were rich enough to do so.

Victories over the Goths by Constantine the Great increased the prosperity of Oescus, but he is especially associated with the city through his bridge across the Danube to connect Oescus with the fortress of Sucidava (Corabia) on the north bank. The importance of this area in trans-Danubian communications as well as defensive strategy is emphasised by the existence of another, unexcavated bridge about 18 kilometres west of Oescus between the fort of Valeriana (Dolni, Vadin) and Orlea on the Romanian bank, built under Domitian.

![]()

125

Plate 81 Oescus, extra-mural complex

Fig. 16 Oescus, extra-mural complex

![]()

126

In July 328, Constantine visited Oescus to inaugurate the bridge which, spanning 2,400 metres, was the longest bridge in Antiquity. Its life must have been short; possibly it was burnt down, for in 367 Valens had to cross elsewhere by means of a bridge of boats. But the substructure remained. Marsigli, in his Description du Danube of 1744, wrote that in the summer of 1691 the water level fell so low that gigantic piers were visible. He mistakenly referred to them as wooden. F. Kanitz described a similar occurrence in 1871. Early in the last century, a Romanian fisherman hauled up a copper crampon, causing a new legend of a gleaming Constantinian bridge of copper to oust all other local traditions.

Romanian archaeologists have found the ruins of three massive stone piers, sunk in the bed of the Danube. [5] Nearly equidistant from one another, with a longer span to the south bank, they were 33 metres long and 19 metres wide, with tapered ends identical to those of Trajan’s bridge near the ’Iron Gates’. It is assumed that the superstructure was wooden, with fortified masonry towers at each end; the northern one has been excavated, but not the southern. These remains are a reminder that in the time of Constantine the concept of Dacia restituta was more than a dream, although one never to be realised. Oescus itself was to fade into oblivion, perhaps destroyed by the Visigoths or, at latest, by the Huns.

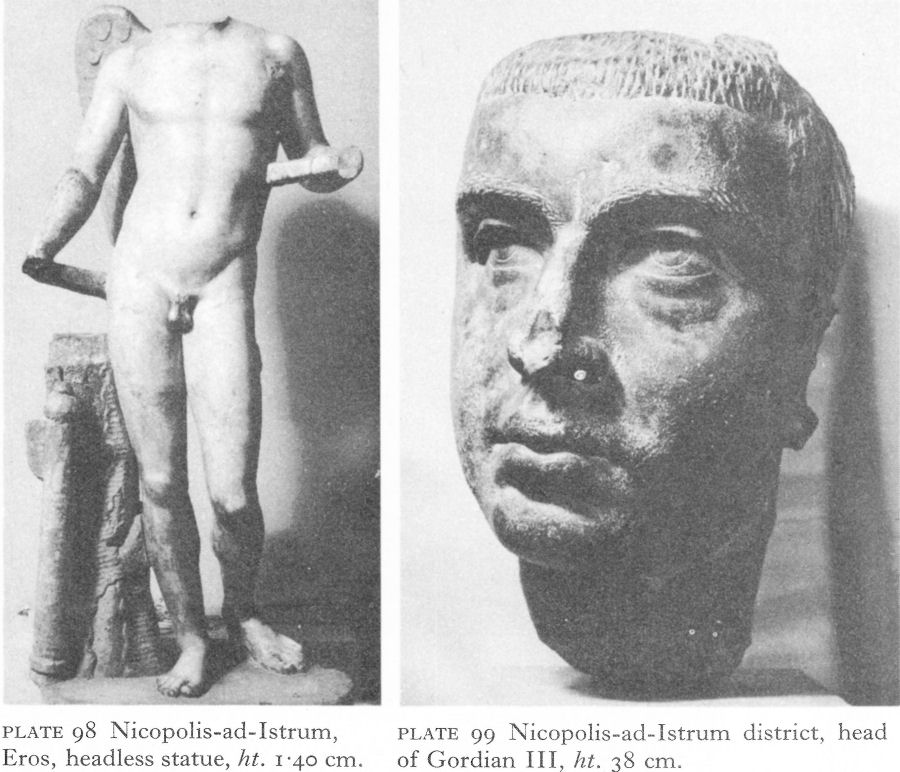

Inscriptions confirm close links between Ad Putea (Riben), a station on the north-south road near the crossing of the river Vit, the ancient Utus, with Oescus and Legio V Macedonica. Paradoxically, its most important find to date is the marble statuette of a ‘peaceful satyr’ (Pl. 82), a lazily smiling boy, naked except for a panther skin. Similar to one from Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli and another from the Palatine, it is considered, like the Eros from Nicopolis-adIstrum (Pl. 98), to be a second-century copy of a statue by Praxiteles.

South-east of Oescus, at Kreta on the river Vit, was the quarry from which came the stone for building the city. Here in an artificial cave was a Mithraeum in which a large relief was found in situ. The plaque, 92 centimetres long and 60 centimetres high, depicting the usual scene of Mithras slaying the bull, stood in a niche on a pedestal, among a number of votive altars.

III. NIKOPOL

A little farther east, past the confluence of the Osum, the ancient Asamus, with the Danube and about half-way between Oescus and Novae, stands Nikopol, where soundings have recently established a stratigraphy to the pre-Roman period. So far its chief claim to fame is a Roman funerary inscription, the elegy of Aelia by her husband, one Fronto, imperial dispensator in Moesia Inferior, which is addressed to the ‘queen of the great realm of Dis’. [6] First he prays for the everlasting peace of his precious love, so that her bones at least may rest in honour, for she deserves much praise, and that Proserpina should bid her dwell in the Elysian fields and bind her hair with myrtle and her temples with blossom. He then eulogises his wife:

. . . Once the spirit of my home [Lar], my hope, my only life; she who wished only as I wished and expressed no desire contrary to mine; with no secrets hidden from me; not lacking in the household arts nor unskilled at the loom;

![]()

127

Plate 82 Ad Putea, statuette, ht. 80 cm.

![]()

128

frugal in domestic management but lavish in marital love; without me taking pleasure neither in food nor in the Bacchic rite; admirable in advice; wise of mind; renowned for her good name . . .

Fronto ends by praying that her monument may be cherished for eternity, by future owners of new and different races, so that in a kindly climate, with the dewy rosebud or the pleasant amaranthus, it shall each year be put in order.

The site of Aelia’s burial is unknown; Fronto was probably stationed at Oescus, or perhaps at Novae, in the latter half of the second century. The fine marble slab, a stele or perhaps the front of a sarcophagus, on which her elegy is inscribed is still in excellent condition - the centrepiece of Nikopol’s public fountain, built at latest by the end of the seventeenth century when Nikopol was a Turkish fortress. In this way at least part of her husband’s prayer has been fulfilled.

IV. NOVAE

Novae (Stuklen, 4 kilometres east of Svishtov) occupies a low, uneven plateau bordered on the north by the Danube and on the east by a little tributary, the Dermen. Like Oescus, earlier the site of a Thracian settlement, from a.d. 46 to a.d. 69 Novae was garrisoned by Legio VIII Augusta. Thereafter it was the headquarters of Legio I Italica for as long as a semblance of Roman military organisation persisted in this vulnerable area. An important road station, Novae also controlled one of the easier Danube crossings. The concentration of two legionary headquarters on this short riparian stretch of about 90 kilometres showed recognition of its strategic importance, apparently better understood by the Romans than by their Turkish successors, for at Novae the Russian army effected an easy crossing into Bulgaria in 1877 to bring the country independence. At the end of the second century, the area was also politically prominent. Septimius Severus owed his throne to the support of the Danubian legions, among which Legio I Italica played an important part.

Although long used as a local quarry, major excavations began here only in 1960, providing a marked contrast with Oescus. Since that date a Bulgarian team has taken the eastern sector and a Polish the western. A fortified area of about 26 hectares has been traced, the approximate extent of the walled town from the end of the third century until the early seventh. The north, west, and south curtain walls have second-century or earlier foundations, but the original east wall was abandoned when the city expanded in this direction. The basically rectangular plan was, as usual, adapted to gain the maximum advantage from the terrain, a bend in the south wall giving, in the third or fourth century, if not before, a slightly pentagonal trace. The north wall, only partially excavated, ran for just over 500 metres along the Danube, here pursuing an almost straight course. The west - and most accessible - side, about 480 metres long and incorporating a monumental gateway, joined the north and south walls at right angles. The south wall, with a centrally sited gate, ran straight for rather over half its total length of 650 metres, then turned slightly northward. The east wall, about 420 metres long, was roughly arc-shaped.

In spite of several building phases, the line of the western defences remained unchanged throughout Novae’s existence. The first wall, of uncertain date,

![]()

129

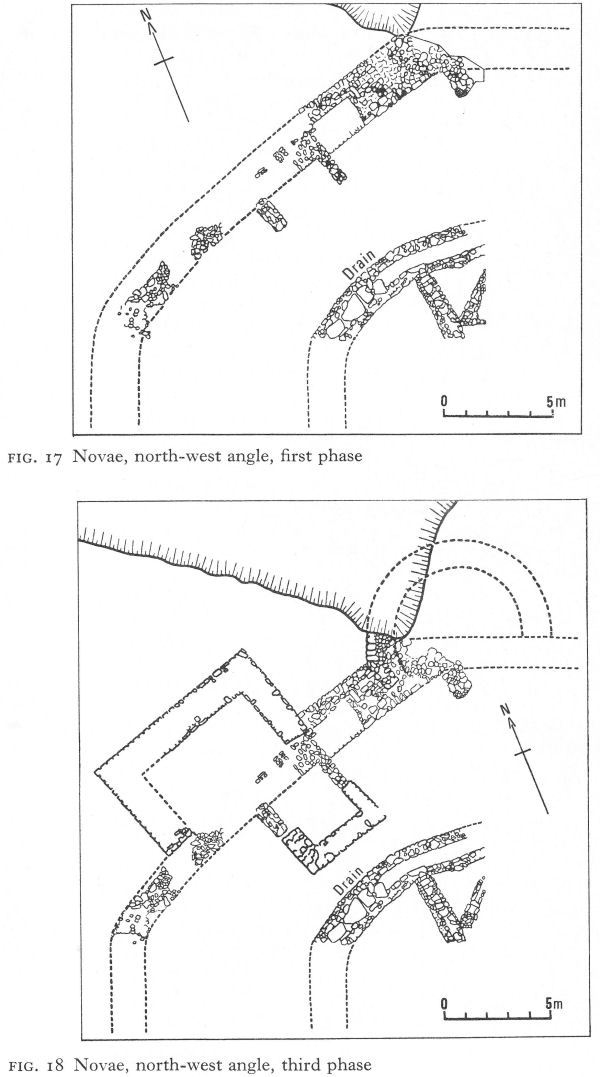

Fig. 17 Novae, north-west angle, first phase

Fig. 18 Novae, north-west angle, third phase

![]()

130

consisted of loose stones piled up and covered with earth. Probably as early as the second half of the first century, this was replaced by a masonry wall, remains of which were found at the north-west corner with, inside, a drain of the same period running roughly parallel. The angle here was rounded off by a flat arc 20 metres long and seemingly strengthened by an internal square tower (Fig. 17). This early wall continued along the Danube, although since little of it has been excavated, its later evolution is unknown. Traces were also found near the west gate. A second stage of the north-west angle occurred when it was destroyed but rebuilt following the same plan. At a third stage, probably during the late third or early fourth century, the wall was reconstructed and strengthened with a rectangular external tower at the middle of the arc. Where the arc joined the north wall there was apparently an external semicircular tower, but its chronological relationship to the other is not clear (Fig. 18). Evidence of several building periods in the inside drain perhaps also indicates enemy penetration. Novae was besieged by the Goths in the mid-third century and was only saved by the appearance of a relief force.

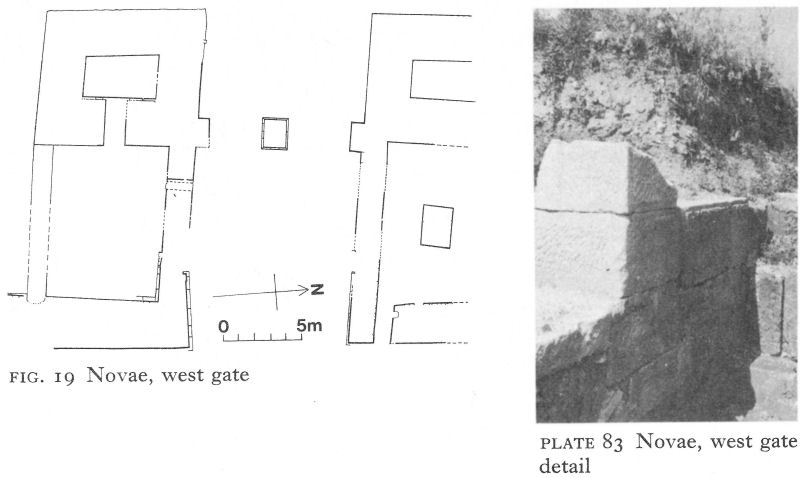

So far the west gate is the most vivid reminder of Novae’s former importance (Fig. 19). It stands just north of the point where the present road breaches the city wall, well within the northern half of the walled area. Preliminary work has established the full width of the gateway as io-6o metres, thus by far the largest known in Moesia Inferior. At the excavated southern end the terminal wall was constructed of large carefully jointed ashlar with a rusticated facing. Below ground level, encased in the foundations of the wall was a vaulted passage, over a metre high and half a metre wide (Pl. 83). This may have been a concealed exit for a surprise night attack on besieging forces, but small enough to defend without difficulty against an attempted entry. The gate is thought to have been constructed in the second century or, at the very latest, the first half of the third, and to have been destroyed and rebuilt during the fourth, to which period are attributed the two external gate towers. As elsewhere, the gate provided evidence of several attacks and repairs.

A well-built horseshoe-shaped angle tower, projecting nearly 10 metres from the south-west corner, can hardly be earlier than the late third or early fourth century. The trapezoidal interior gave the walls a thickness varying from 3.20 to 4.50 metres (Fig. 20). The lower part was faced with large well-cut limestone blocks, the mortared joins strengthened with iron cramps. The obviously later upper levels were of opus mixtum (stone strengthened at intervals with bonding courses of brick), and the masonry was faced with smaller, more roughly cut stones and unusually poor mortar (Pl. 152).

At least nine towers have been identified in the east sector; five, all external, in the excavated part of the east wall south of the present road were either square or rectangular. Going from north to south, tower 1 was built above two earlier constructions, the first late Hellenistic or early Roman, the second incorporating a stone pavement which extended beyond the interior floor and foundations of the wall. In the tower, mid-fourth-century coins, none later than Valentinian I, suggest it may have been built in the reign of Constantine the Great and then destroyed by the Visigoths. Thereupon its military significance ceased; a later dividing wall probably converted it into a dwelling.

The fourth and largest tower on this wall defended the south-east angle (Fig. 21).

![]()

131

Fig. 19 Novae, west gate

Plate 83 Novae, west gate detail

Fig. 20 Novae, south-west angle tower

Fig. 21 Novae, south-east angle tower

Plate 84 Novae, S.E. angle tower, interior detail

![]()

132

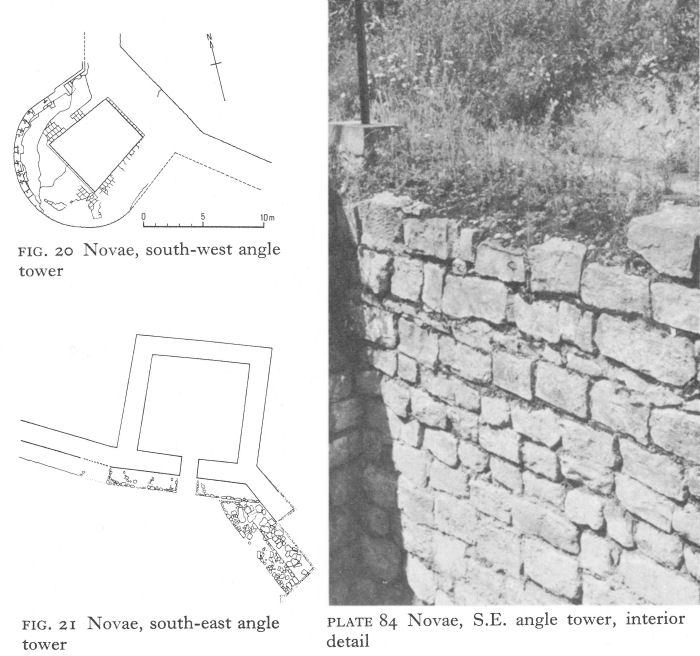

Fig. 22 Novae, rectangular tower (no. VI)

Fig. 23 Novae, U-shaped tower (no. VIII)

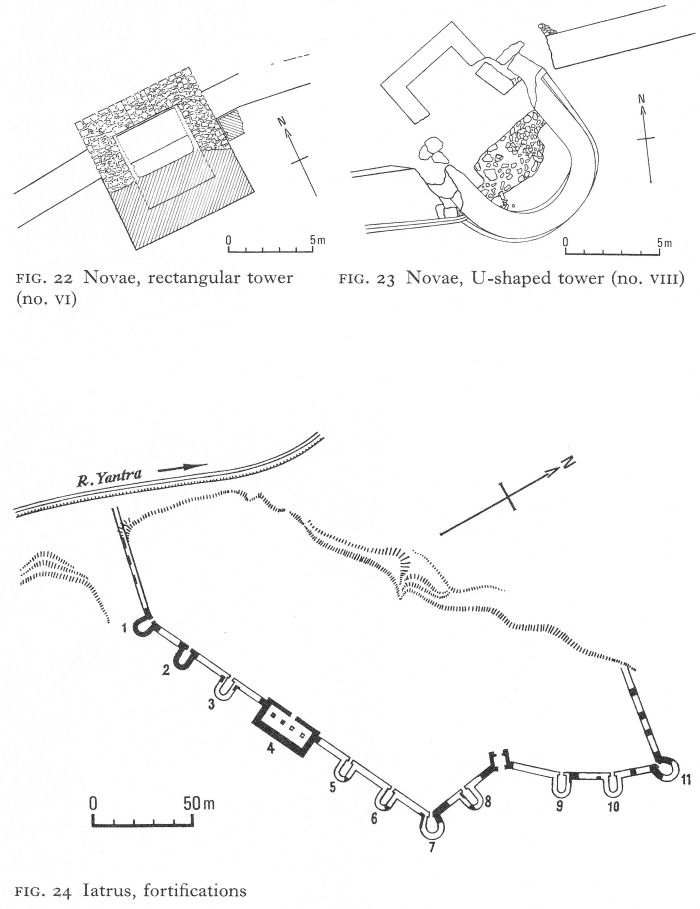

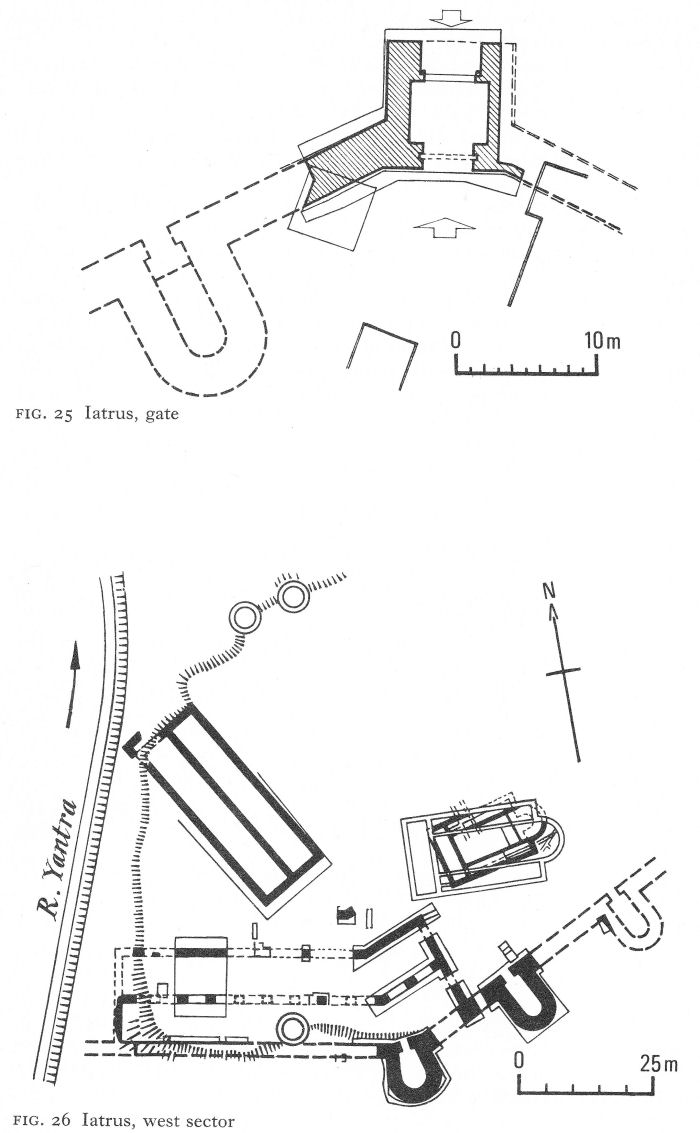

Fig. 24 Iatrus, fortifications

![]()

133

It projected about 8 metres and had an exterior width of about n metres. Two distinct building periods have been identified, both within the fourth century (Pl. 84).

Those between the angle tower and the south gate were more varied. Beyond a smaller, square version of the first four was a rectangular tower, no. vi (Fig. 22), which, standing in a slight re-entrant, projected inside as well as, to a greater extent, outside. Another, referred to as no. VIII, was a U-shaped structure linking two unaligned sections of the curtain wall (Fig. 23). Rather surprisingly, it seems relatively weak, with walls only 1 metre thick at the peak of the curve and just over 1 1/2 metres at the sides. This compares with the curtain wall’s thickness of 2.80 metres. The tower bore marks of considerable damage and was rebuilt several times. An adjacent U-shaped external tower had walls about 2.60 metres thick at the sides and nearly 3 metres at the middle.

The curtain wall and towers on the east side of the town appear to have been built after the Gothic wars of the third quarter of the third century and before those of the Visigoths in 376-82. With many repairs and reconstructions, some of which were put into effect before the end of the fourth century, it seems likely to have remained more or less the east line of defence until the beginning of the seventh century. But its relationship to the original east wall has still to be resolved.

Within the walls excavations are bringing to light parts of large buildings, houses and streets, one of which clearly displays two levels, with porticoes, shops and workshops, and many minor finds. Co-ordinated soundings were made by the two teams in 1971 to locate the forum.

V. IATRUS

Iatrus or Iatrum (Krivina) lies on the right bank of the Yantra - in Antiquity the Iatrus, from a Thracian word believed to mean a swift, turbulent river - close to its entry into the Danube, about 16 kilometres east of Novae. Unlike cities such as Ratiaria and Oescus, Roman Iatrus was a fort without significant administrative functions or civilian population on the highway between Novae and Durostorum (Silistra). K. Škorpil traced the walls in the early 1900s and found a Latin inscription of the first half of the second century. Joint excavation by Bulgarian and East German archaeologists, begun in 1958, shows that it was a castellum, a small fortified centre, of strategic importance in the fourth century, when the fortifications uncovered were constructed. A re-used altar dated to the second or third century and dedicated to the ‘invincible god’ Mithras by one Marcus Ulpius Modianus of Legio I Italica links it with Novae. Unfortunately, the Yantra, which once guarded the western walls, has since eroded them, together with an unknown proportion of the castellum, through which it now flows. Flood waters of the Danube have similarly destroyed the north-western part, leaving an irregular lozenge-shaped plateau, 300 metres long with a maximum width of 100 metres (Fig. 24).

The curtain wall was a massive structure about 3 1/2 metres thick, faced on the outside with large rusticated ashlar blocks, the interior dimensions diminishing slightly to avoid mortar being visible on the outside. The western end emerges now from the edge of the cliff which drops down to the Yantra’s present course

![]()

134

and first runs without towers at a right-angle to the river, a steep slope to the south denying easy access. After a slight bend, a long straight stretch follows, with external horseshoe-shaped angle towers at each end (nos. 1 and 7). A large rectangular tower in the middle (no. 4) had two U-shaped ones on either side of it. From tower 7 the wall turned at a near right-angle to make a deep re-entrant which incorporated the gateway and was reinforced by U-towers. It terminated in the horseshoe-shaped angle tower n. The wall then turned sharply to the west, now to disappear into the sector eroded by the Danube.

The walls of the U-shaped and angle towers were 3 metres thick and projected about 9 metres from the curtain wall. The rectangular tower, no. 4, was even more substantial; 30 1/2 metres long and 15 metres deep, it projected 9 1/2 metres beyond the wall and nearly 2 1/2 metres inside it. Within the tower, four great rectangular stone piers, 1.77 by 1.19 metres, standing on 2-metre deep foundations, were aligned along the axis, evidently to support an upper storey capable of carrying artillery such as ballistae and supplies of stone balls. The tower must have given powerful protection to the relatively easy south-eastern approach to the fort. Similar rectangular structures appear in castella in the Dobroudja, notably at Capidava and, without piers, at Tropaeum Trajani.

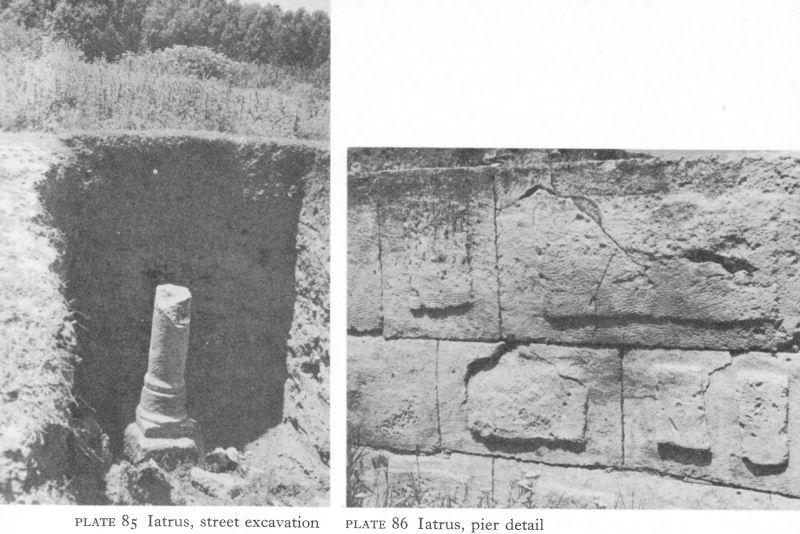

Little is left today of the only surviving gate. Facing south-east, between but not architecturally linked with towers 8 and 9, it was double and recessed so that its exterior face lay flush with the wall (Fig. 25). The outer gate, 4 metres across, a portcullis, operated between grooves running down the jambs. A space, the propugnaculum, 5 1/2 metres square, separated it from the inner door, which consisted of two pivoted wings. Inside, two gravel-laid streets, both decumani, east-west streets, have been uncovered; one of these was colonnaded (Pl. 85).

One excavated building extended parallel with the wall from its present western end for a distance of 62 1/2 metres, including the first angle tower. It replaced earlier Roman constructions about which little could be ascertained (Fig. 26). The outer wall was formed by the curtain wall. The inner, 12 metres away and, like the two short ends, 1 1/4 metres thick, was of opus mixtum, with remains of only one layer of bricks just discernible. Following the pattern of the rectangular tower, nine piers and pilasters at each end lined its axis. The piers, the majority 1.50-1.60 by 1.80-1.90 metres, were built of finely jointed ashlar, joined by iron cramps and decorated with simple shapes in relief (Pls. 86, 87). Traces of vaulting confirm that they supported an upper storey. This building, later than the curtain wall, must have had some complementary military purpose, such as a storehouse; apart from backing on to the wall, tower 1 could only be entered from it. Like tower 4, artillery could be carried on the upper storey. The careful workmanship of the piers - the facing of the walls has been completely lost - and traces of a tiled floor have close parallels in the walls and towers of Tropaeum Trajani.

Foundations and parts of walls of one other building of the same period, a large rectangular structure 39 metres long and 14 metres wide, were excavated just north of the building described above. Its walls, 1.20 metres thick, were of opus mixtum, using bands of four courses of bricks. A stylobate to carry piers or columns down the centre indicates an upper storey.

![]()

135

Below the building were earlier constructions, including walls of stone and mud and, still lower, a male inhumation burial without grave goods.

In a nearby sector, soundings revealed rather confused evidence of two early building periods. Both were Roman and here, too, were the remains of two stone and mud walls. The first was like the earliest constructions found at Serdica and Abritus, as well as those below the rectangular building, and may date to the first century a.d. At the second level were floors of stone with white mortar. T. Ivanov suggests that the earlier was destroyed during the mid-thirdcentury Gothic invasion; and that the second existed between the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth - it may have been contemporary with the walls - and the late fourth century, when the site was prepared for a Christian basilica (p. 245).

Coin finds, analogies with other Balkan sites, and structural features suggest the walls were built during the period of refortification of the Danube limes by Licinius, Galerius, and Constantine the Great. The long building attached to the wall at the western end was added during the second half of the fourth century or, at latest, the beginning of the fifth. The other rectangular building also belonged to the second half of the fourth century, probably prior to the Visigothic invasions of 376-82.

VI. TRANSMARISCA

West of Durostorum, the castellum of Transmarisca (Toutrakan) occupied the strategic site of an earlier Thracian settlement opposite the confluence of the Danube and the (Romanian) river Arges - the Mariscus of Antiquity. Existing from the second century, the earliest parts of the stone fortifications now being excavated are thought more likely to belong to the late third century, when the fort was garrisoned by detachments of Legio XI Claudia. This connection with Durostorum, which was to continue to be the legion’s headquarters until the sixth century, is confirmed by the find of stamped bricks.

A late third-century inscription honouring Diocletian for his victories over the barbarians, his restoration of peace to the land, and his erection of the praesidium, or fortress, of Transmarisca may mean that the original fortifications had been destroyed by the Goths and that those now being uncovered are the work of Diocletian. Almost identical inscriptions have been found at Sexaginta Prista (Rousse) and Durostorum.

The importance attained by Transmarisca in the fourth century is shown by Valens’ choice of it as a base from which to build a pontoon bridge across the Danube to pursue his campaign against the Visigoths.

VII. DUROSTORUM

Durostorum (Silistra) replaced a Getic oppidum, a fortified hilltop settlement, probably conquered by the Romans early in the first century a.d. To the north, a wide marshy sector of the Danube, extending almost to the delta, protected the Dobroudja. Troesmis (in modern Romania) defended its northern end, Durostorum its southern, and, of greater importance from the point of view of imperial defence, the approach to Marcianopolis, Odessos, and easy passes of the Stara Planina to the south.

![]()

136

Fig. 25 Iatrus, gate

Fig. 26 Iatrus, west sector

![]()

137

Plate 85 Iatrus, street excavation

Plate 86 Iatrus, pier detail

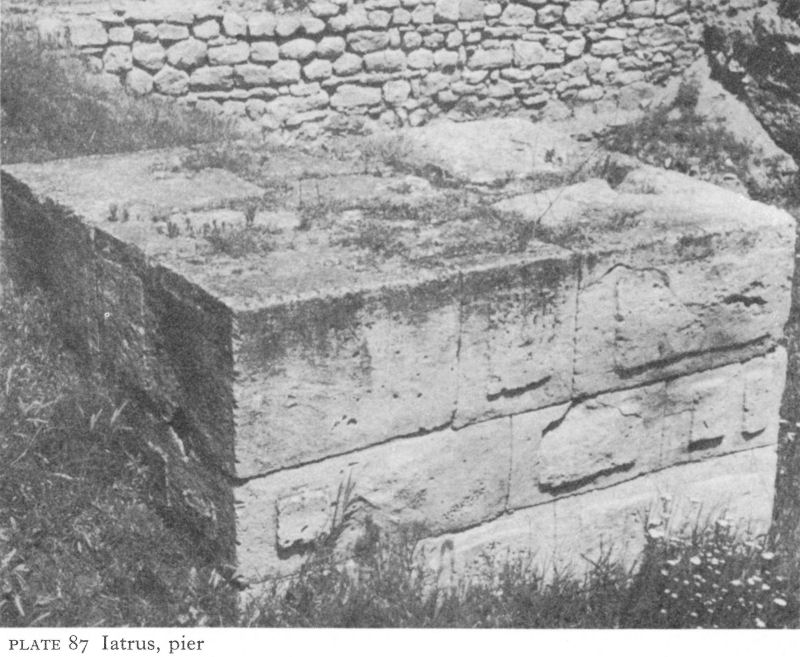

Plate 87 Iatrus, pier

![]()

138

Plate 88. Durostorum, helmet-mask, ht. 25,3 cm.

Plate 89 Siiistra district, Athena, head, ht. 33 cm.

Plate 90 Silistra district, Mithraic relief

Following the First Dacian war of 101-2, during which Decebalus had crossed the Danube near Durostorum to invade Moesia Inferior, the city became the headquarters of Legio XI Claudia and remained so until the legions were replaced by foederati. At the same time, Legio V Macedonica was temporarily transferred to Troesmis. Hadrian visited Durostorum in 123-24 and a flourishing settlement soon grew up - the canabae Aeliae - round the legionary headquarters, to become a major centre for the Romanisation of this part of Moesia Inferior. The settlers were mainly veterans of Italic and Western origin - some from Ratiaria and Oescus but many from Spain, Gaul, Germany, and Britain. Cohors II Flavia Britonum was stationed temporarily here. By the third quarter of the second century, Durostorum had become a municipium, a city granted considerable civic autonomy, and, with the departure of Legio V Macedonica to Dacia, Durostorum was left the sole legionary headquarters on the Danube east of Novae.

Many Getai still lived outside the town - and occupied lowly positions within it.

![]()

139

Some degree of integration is shown by the funerary monument of a legionary, he and his wife apparently of Italic origin but their sons all bearing Getic names, including Decebalus. Some of the hinterland had been settled by members of the warlike Bessi tribe, transported from the Rhodopes and here given favoured status. Besides normal legionary cults, notably Mithraism, an altar was erected by a group of soldiers to the ‘Heros Suregetes’, a probable reference to the Thracian Hero - of whom there is more evidence in the countryside - the epithet being similar to one used at Bessapara (near Pazardjik).

The area suffered severely from a combined invasion of the Karps, Goths, and Sarmatians in 238. A votive tablet from an inhabitant of Durostorum thanks the gods for preserving him from captivity, a fate clearly met by many others. An official inscription thanked Aurelian for his work of reconstruction. Nevertheless, for the next hundred years the Danube defences in the neighbourhood remained vulnerable to the northern tribes lured by the wealth of the coastal cities, notwithstanding an attempt at pacification and political-religious penetration by means of Christian missionary activity in the middle decades of the fourth century.

Durostorum must have played a part in Valens’ campaign against the Goths - he was there in the autumn of 367 - but after his defeat and death, although the fortified town survived, disaster overcame the countryside.

The existence of the modern frontier city of Silistra and erosion by the Danube have until recently prevented much excavation of the site, the earliest fortifications so far discovered being some Early Byzantine foundations of the fortress wall. There are some chance finds, such as a bronze helmet-mask [7] (Pl. 88) attributed to the first or second century, a probably third-century marble head broken from a statue of Athena (Pl. 89), a Mithraic relief in lively local style (Pl. 90). But although the main archaeological remains of Roman Durostorum are hidden, its name is famous in Christian hagiography for the martyrs, chiefly of Legio XI Claudia, who suffered for their faith under Diocletian and Galerius.

The story of the best-known soldier martyr here, St Dasius, is linked with the troops’ custom of celebrating the Roman feast of the Saturnalia. Lots were drawn, the winner designated ‘king’ and allowed a month’s ‘reign’ of unbridled licence, then put to death as a sacrifice to Cronus. In 304, the lot fell to Dasius, a Christian legionary. Knowing he could not escape death, Dasius rejected his Saturnalian role, was thrown into prison, and killed. [8] After the general adoption of Christianity, a cult of St Dasius developed, centred on the shrine containing his relics. Later, perhaps in the second half of the sixth century, the barbarian danger grew so great that the relics were transferred for safety to the cathedral of Ancona. Here they lay in a sarcophagus inscribed in Byzantine Greek with his name and the city of his martyrdom, to be rediscovered in 1908.

A second legionary martyr was Julius, whose story is touching both for the stubbornness with which a veteran of seven campaigns and 27 years’ unblemished service refused to sacrifice to the pagan gods and for the well-meaning attempts of the prefect to devise a face-saving formula to satisfy Julius’ conscience and yet comply with the letter of the law.

If you think it a sin, [the prefect said], let me take the blame. I am the one who is forcing you, so that you may not give the impression of having consented voluntarily. Afterwards, you can go home in peace, you will pick up your ten-year bonus and no one will ever trouble you again. [9]

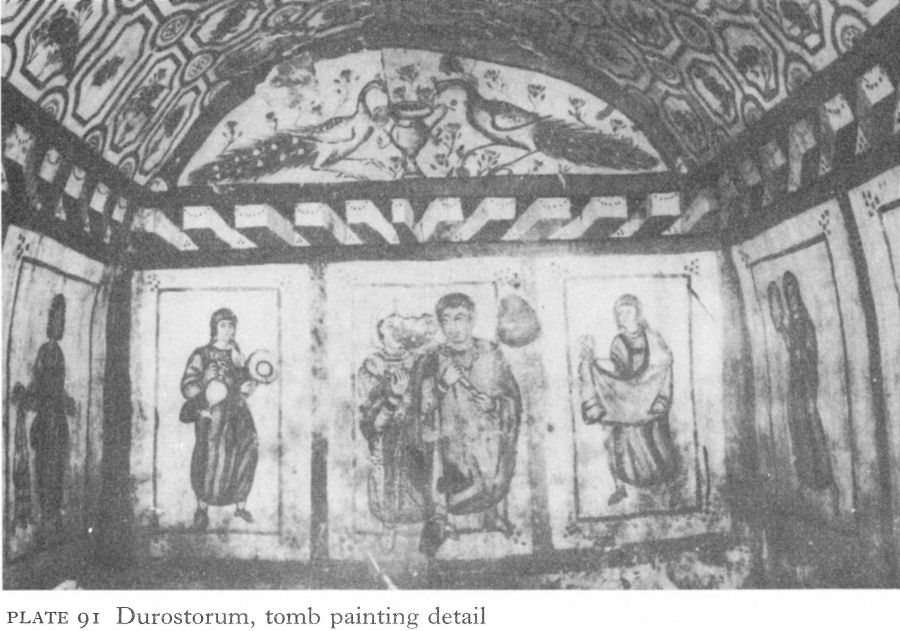

![]()

140

Plate 91 Durostorum, tomb painting detail

All his persuasions were of no avail. Julius insisted on being beheaded.

Nevertheless, a painted pagan tomb is the most important surviving monument of the fourth century in Durostorum. The almost completely preserved painted decoration covers both walls and ceiling of an ordinary Roman masonry tomb chamber, aligned east-west and measuring 3.30 by 2.60 metres, with a shallow brick-built vault rising to a height of 2.30 metres in the centre. The entrance is in the middle of the east wall.

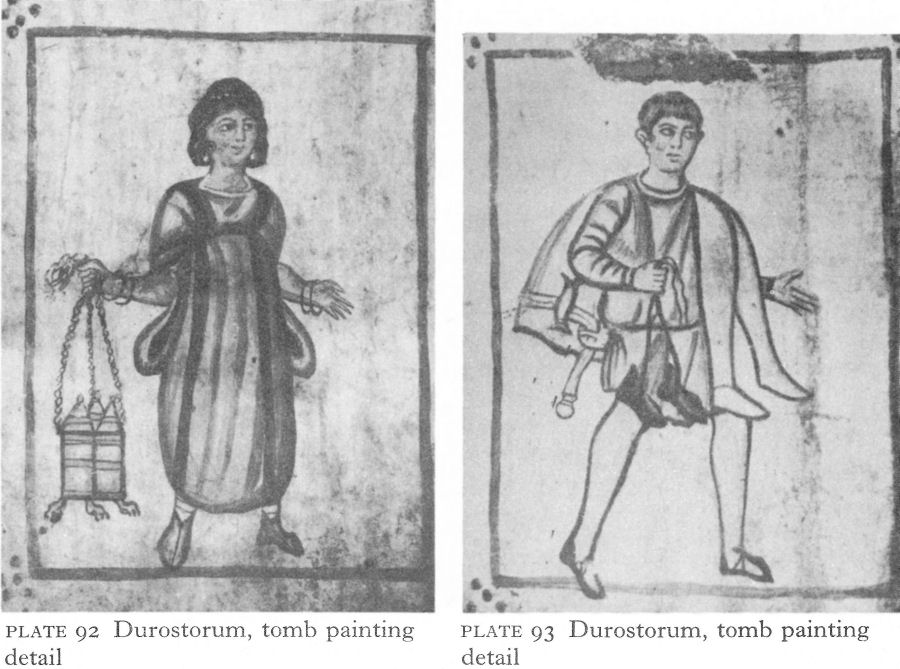

Round the walls, a series of rectangular panels a little over 1 metre high and 1 metre wide and enclosed by tile-red borders contain lively portraits of a man, his wife, and their household. Within the light background of the panels, a second rectangle, outlined in dark green, sets off each figure. The master and his wife occupy a joint, wider panel, facing the entrance (Pl. 91). They stand with heads turned towards each other, but whilst she gazes at her husband, he looks into the distance, obviously preoccupied. He carries a scroll; she rests one hand on his shoulder and holds a rose in the other. The heads are unnaturally large, possibly a conventional indication of their rank or status. He wears a long tunic with full-length sleeves and decorated cuffs under a loose mantle fastened by a fibula at the shoulder. A white kerchief hides almost all the wife’s brown hair. She, too, wears a long tunic, over which is a white dalmatic splashed with grey and an embroidered ochre and red clavus or vertical stripe.

Maidservants are advancing in the panels on either side; one carries a jug and a long-handled dish, the other a drape; next, on the side-walls, are two more, one holding up a mirror and another bearing three jars in a special holder, perhaps for her mistress’s toilet (Pl. 92).

![]()

141

The last wears a bead or pearl circlet in her hair, rings in her ears, and two bangles on each wrist - and the smug expression of a favourite. Next, a youth carries over his shoulder a pair of tights, complete with belt, one hand holding a pair of shoes by their laces (Pl. 93). Like the other menservants, his dress is a short, long-sleeved, belted tunic, reaching to just over the knee. Behind him a boy is carrying and adjusting the folds of a mantle; his hair down to his shoulders probably indicates a Gothic slave. On the opposite wall are two more youths, both wearing torques, one holding a napkin and the other carrying a heavy ornamental belt. On either side of the door, narrower panels each enclose an ornate candelabrum, the candles alight and wax spilling down their sides. Above, a painted band gives a rather crude impression of beams projecting from a building into a courtyard, the central court of a modest Roman villa.

In the west lunette, above the beams, two peacocks drink from a vase, against a floral background. This symbol of immortality is so common in early Christian iconography that the tomb was at first considered Christian, an idea supported by the orientation as well as, no doubt, by the hagiographical reputation of Durostorum. In the east lunette, the scene is repeated with smaller birds, perhaps doves. The vault is covered by a network of tiny panels enclosing rural motifs - flowers, fruit, palm trees, birds, animals, and hunters - no two the same.

The paintings in the tomb, probably built in the second half of the fourth century and apparently never used, are unusually interesting, although naturally provincial in style. Clearly commissioned by the two prospective occupants, it presents a delightful picture of the bourgeois Roman citizen at home in this

Plate 92 Durostorum, tomb painting detail

Plate 93 Durostorum, tomb painting detail

![]()

142

corner of the empire. By comparison with those in the Kazanluk tomb of some six hundred years earlier (Pls. 63-5), the paintings lack any note of mourning. Superficially the scene is similar, but here death is shown as a perpetuation of the pleasanter aspects of life. Only the lunettes carry reminders of immortality, but it is an afterlife in which ordinary people continue in their appropriate earthly station. The roughly contemporary saints’ heads from the fourth-century church at Tsar Krum (Pls. 163, 164) present as great a contrast in their spirituality as do the dignity and solemnity of the Thracians of Kazanluk.

However, Christianity developed strongly in fourth-century Durostorum, reinforced by the teaching of the Arian Gothic translator of the Bible, Ulfilas, one of whose pupils, Auxentius, a leading protagonist of Arianism, became bishop of the city in 380. Meanwhile the martyrdom had happened in 362 of another famous local saint, Aemilianus, during Julian’s brief persecution. Julian’s representative, Capitolinus, was appointed to enforce the revival of the old cults. During a huge banquet to celebrate his achievements, Aemilianus entered an unattended pagan temple, smashed the idols with a hammer, upset altars and candlesticks, spilt the libatory wine, and departed unseen. The furious Capitolinus ordered an inquiry, punishment of the temple guards, and the immediate apprehension of the culprit. No time was lost in arresting an innocent peasant passing by and dragging him to the praetorium to be executed. This demonstration of zeal was upset by Aemilianus’ confession of responsibility. His bold replies to Capitolinus’ questions enraged the envoy, who ordered him to be thrown to the ground and beaten. When Aemilianus admitted he was the son of a prefect, Capitolinus imposed a heavy fine on the father who had brought his son up so badly, and sentenced the latter to be burnt alive. But the flames, respecting his body, devoured the soldiers instead. Aemilianus then made the sign of the cross, commended his soul to God, and expired in peace. The story achieved much fame in succeeding centuries and, as can be seen, did not lose in the telling as it became part of the Christian tradition of Moesia. [10]

NOTES

1. Gerov, B., Romanizmut III, no. 186.

2. Velkov, I., IBAI XIV, 1940-42, 183 ff.

3. NAC, Arh XIII/4, 1971, 78.

4. Pap. Ox. XXVII 2462, discussed in Charitonidis, S., Kahil, L., and Ginouves, R., Les mosaiques de la maison de Ménandre à Mytilène, Berne, 1970, 98-9.

5. Tudor, D., Sucidava; une cité daco-romaine et byzantine en Dacie, Brussels, 1965, 74 ff.

6. CIL III Supp. 7436.

7. Venedikov, I., Eirene I, 1950, 143 ff.

8. Analecta Bollandiana XVI, 1897, 5 ff.; Zeiller, J., Les origines chretiennes dans les provinces danubiennes de l'empire romaine, Paris, 1918, no ff.

9. Musurillo, H., The Acts of the Christian Martyrs, Oxford, 1972, 263.

10. Analecta Bollandiana XXXI, 1912, 260 ff.

6 The northern foothills (I)

I. NICOPOLIS-AD -ISTRUM AND THE CENTRAL SLOPES

Nicopolis-ad-Istrum

Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, 18 kilometres north of Veliko (Great) Turnovo, was identified in the last century by F. Kanitz who, studying Roman ruins still known locally as ‘Stari’ or ‘Old’ Nikyup near the present village of Nikyup, found the base of a statue erected in 203 by the council and assembly of Nicopolisad-Istrum to Julia Domna, wife of Septimius Severus. The resulting official treasure hunt produced many finds, but the site, like Oescus, was left in disorder and unrecorded. Recent research and limited excavation have established some major features, but these can only be regarded as a beginning of an enormous but rewarding task.

Nicopolis-ad-Istrum - Trajan’s ‘city of victory on the Danube’, founded in 102 in celebration of the Danubian battle which brought the First Dacian war to a victorious conclusion - was probably the emperor’s first foundation in Thracia, then extending some way north of the Stara Planina. The main purpose was restoration of the economy of a fertile area devastated by the Dacian invasions of 85-86 and 101-2.

The chosen site was an important crossroads. Three roads led north to the Danube, two apparently to Novae, the other to Sexaginta Prista; two ran south over the Stara Planina, one over the Shipka pass to Philippopolis and the other more easterly to Augusta Trajana-Beroe. The city also stood on the road roughly parallel with the Danube which linked Marcianopolis and Odessos with the west, joining the Oescus-Philippopolis road at Melta and, farther west, the highway connecting Ratiaria with Lissus on the Adriatic. Only the city’s vulnerability under the impact of later invasions caused the inhabitants to move a short distance south to Turnovo, a stronghold which later developed into the capital of the second Bulgarian kingdom and is one of Bulgaria’s leading cities today.

Nicopolis, as its name implies, was neither a ‘colonia’ nor a ‘municipium’, but founded as a Hellenistic city. Romanisation was a costly business and generally considered unnecessary in Hellenised lands except for overriding reasons of military necessity. The Danube limes was one such exception and behind it the main objective was to achieve stability as economically as possible, with a sufficient prosperity to subsidise the empire and its armies. So, with Roman encouragement, once more a wave of Greek - or Hellenised - immigrants arrived from Asia Minor and also from Syria, and found opportunities for their skills and commercial acumen that would have been the envy of the founders of the Black Sea colonies. With all the advantages of its situation, Nicopolis prospered rapidly during the second century, stimulating industries such as the ceramic factories at Hotnitsa and Butovo and emporia, or official rural marketing centres, such as at Butovo and Discoduratera (Gostilitsa). Many of the wealthier citizens were landowners and had country villas. Inscriptions show that often the proprietors were Roman or Romanised - Novae was only some 50 kilometres way - and although the city’s official language was Greek, the educated citizens were almost certainly bilingual.

![]()

143

Plate 94 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, aerial view

![]()

144

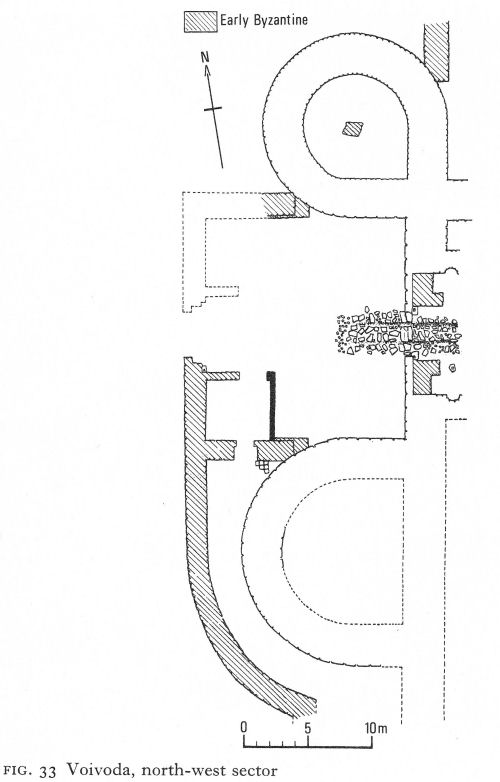

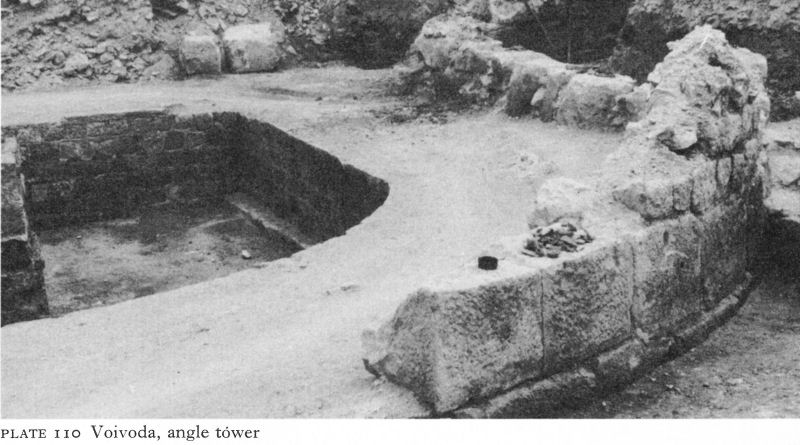

The city was on a low plateau, sloping steeply on three sides either to a gully or to the river Rositsa. With the north-east corner cut off to conform with the terrain, the area enclosed was pentagonal rather than rectangular, 450 metres long on the west side and 505 metres long on the south, on which side the curtain wall partly coincided with the north wall of a smaller, irregularly shaped fort, the towers of which projected into the city proper. At first glance this suggests an earlier castellum, but an aerial photograph (Pl. 94) reveals a much more complicated situation. [1] The ‘fort’, besides rounded angle towers, apparently had others - U-shaped or semi-circular, rectangular, possibly triangular, and even pentagonal, thus suggesting various dates from the end of the third or fourth century into the Byzantine period.

The city’s curtain walls also lack homogeneity. Except at the angles, no towers or bastions are discernible on the south side. Along the west wall it is possible to make out one U-shaped tower and another in the form of a horseshoe; there may be others. In the western half of the north wall, two semicircular towers are visible; at the join with the eastern half, an external rounded angle tower is less clear. The east wall is again different; it is strengthened by two circular half or three-quarter projecting towers; the northern angle tower seems to be external and rounded, but the site of a southern one is occupied by the angle tower of the ‘fort’. Pending excavations, none of the main fortifications of Nicopolis can be regarded as earlier than the second century, whilst those of the southern ‘fort’ may perhaps date to the end of the fourth or the fifth century.

![]()

145

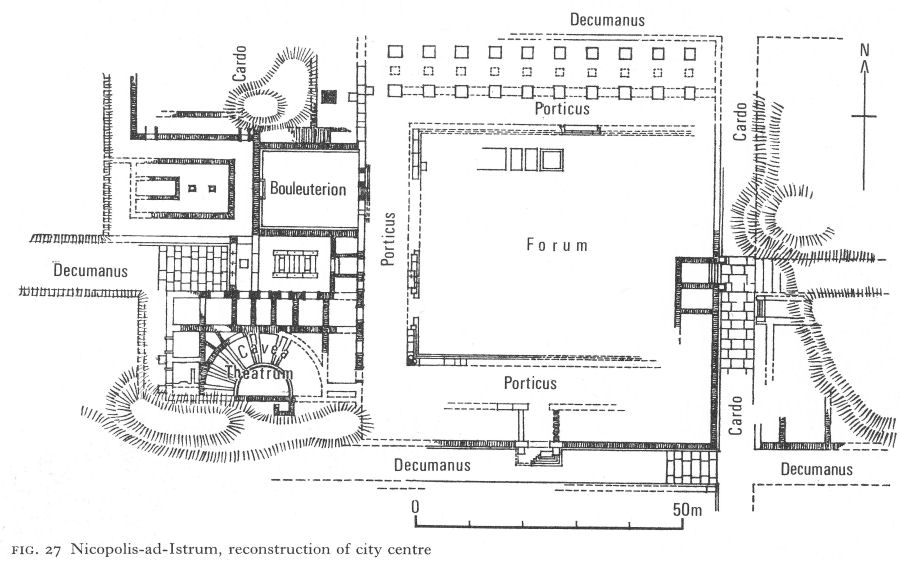

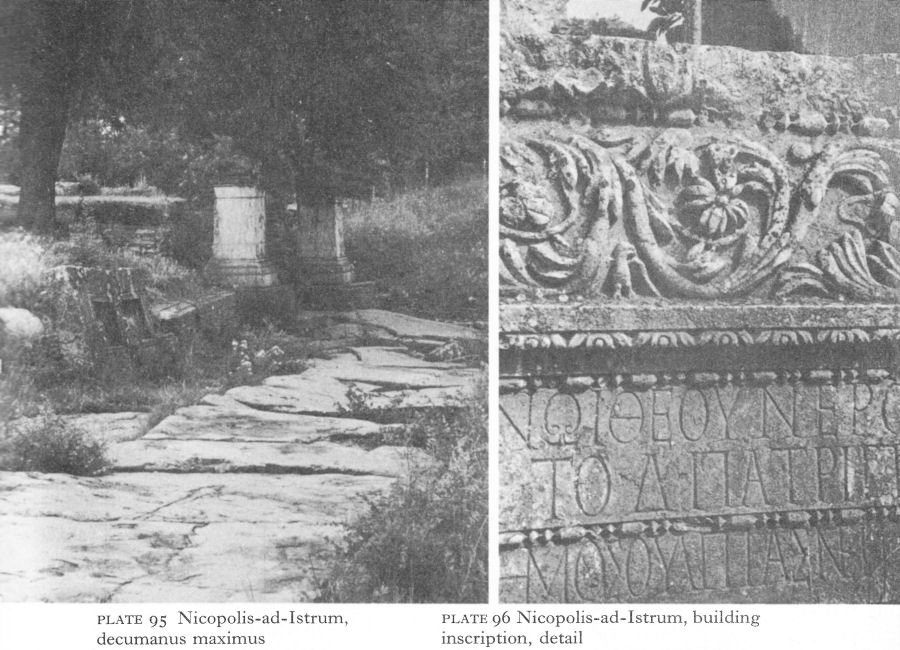

The city had two gateways, one on the north, the other on the west. Starting from the former, the cardo maximus, or main north-south street, continued past the east side of the forum to the annexed ‘fort’. The decumanus maximus, running from the west gate along a line slightly south of the east-west axis, led into a large central area comprising several public buildings and the forum (Fig. 27). The streets, paved with large stone slabs, irregularly laid, probably to minimise earthquake damage, covered the drainage system (Pl. 95).

The space enclosed by the inner portico of the forum was 42 metres square, paved with huge, well-cut stone slabs. The colonnaded portico stood three steps higher; its Ionic bases, monolithic columns, capitals, and architraves were carved from limestone from the nearby Hotnitsa quarries. Rows of shops on the east and south porticoes probably had frontages to streets five or six steps below. The north side is unclear. Finds included two parallel rows of large square bases, with a row of smaller ones between.

The main entrance to the forum was on the west, where the decumanus maximus stopped at a propylaeum, or monumental entrance, of four great Corinthian columns, 8 metres high, a coffered ceiling and a richly decorated architrave (Pl. 96). The Greek inscription on the last shows it was erected by the city in 145 in honour of Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and his wife, Faustina the Younger. [2] The propylaeum led to a narrow peristyled courtyard, from which, between two rooms, access was obtained to the forum’s western portico.

North of this courtyard was the bouleuterion, or council chamber, with a frontage of 15 1/2 metres on the forum portico. Its walls were lined with stone seats and many fragments of inscriptions recording civic decrees and pedestals of statues were found among the ruins.

On the south side of the courtyard the odeon, a rectangular, roofed theatre, had a 26-metre frontage on the forum. The scena occupied the south side; in front, tiers of seats rose round a semicircular orchestra, the lower benches being stone and the upper, probably, of wood, in all sufficient to accommodate some three or four hundred spectators. The front seats were high, giving protection to spectators of gladiatorial combats and displays involving wild beasts. Rooms under the upper tiers were probably shops, those on the western side profiting from facing on to the forum portico.

The plan and architectural style of the forum and the conventionalised representations of public buildings and city gates on coins reflect the dominant influence of Hellenistic Asia Minor. This is supported by the many Greek inscriptions, altars to oriental gods, and architectural fragments littering the central area. In some cases these bear such ‘signatures’ of the master masons as a lizard (Pl. 97) or a dog. There must have been masons’ guilds, just as inscriptions show that there were guilds of woodcarvers, leather-workers, and fullers, again on an Eastern pattern. Nicaea, Nicomedia, and Antioch in Syria are the only towns mentioned as origins of the settlers, but the many Greek names and gods displayed on coins and mentioned in votive inscriptions, such as Priapus, said to have been brought from Bithynia, Sabazius, the associated cult of Magna Mater, Serapis, Mithras, and others, as well as those of the GrecoRoman pantheon, are additional evidence of oriental immigration. The city may also owe to this influx a fine white marble statue of Eros (Pl. 98), believed to be a mid-second-century copy of that carved by Praxiteles for the city of Parion and now known only from its coins.

![]()

146

Fig. 27 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, reconstruction of city centre

![]()

147

Plate 95 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, decumanus maximus

Plate 96 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, building inscription, detail

Plate 97 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, architectural detail

![]()

148

Plate 98 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, Eros, headless statue, ht. 1.40 cm.

Plate 99 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum district, head of Gordian III, ht. 38 cm.

Huge quantities of coins were issued during the period of prosperity. Subjects represented naturally included Nike, and also Haimos, the personification of the Stara Planina, shown as a young hunter, half-reclining on a rock but holding a spear; in front of the rock is a bear, sometimes attacking a stag by the tree behind it. According to the coins, temples were dedicated to deities including Zeus, Apollo, Artemis, Concordia, and Fortuna.

Early in his reign Septimius Severus transferred Nicopolis and its surrounding territory from Thracia to Moesia, which greatly increased the city’s economic opportunities. His subsequent visit in 202 enabled the citizens to demonstrate their gratitude; the celebrations included a gift to the emperor of 700,000 denarii and the many finds of inscriptions and bases of statues of him and his family testify to his popularity. The first third of the third century saw the peak period of Nicopolis’ prosperity. The earliest serious breach of the Danubian defences of Moesia Inferior occurred during the reign of Gordian III. Aptly, in the circumstances, the bronze head of a statue of this emperor (Pl. 99) was found in the bed of the river Yantra some 10 kilometres to the north, possibly where it had been dumped by a retreating looter.

In 250, the Goths, having failed to take Novae, invested Nicopolis, but suffered a severe defeat.

![]()

149

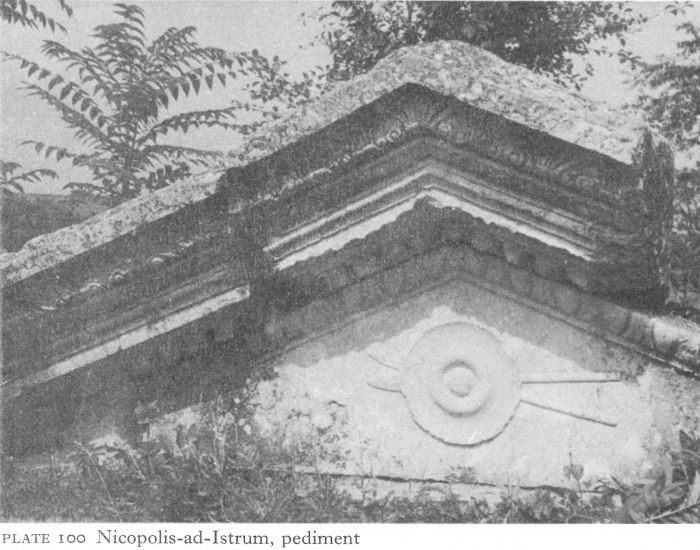

The event establishes the existence by this period of the city walls. Further confirmation comes in Nicopolis’ survival during the Gothic rampages of the next 20 years, culminating in another unsuccessful siege in 270. Aurelian’s withdrawal from Dacia added the loss of a valuable market to the economic distress caused by the Gothic devastation. It also brought the barbarian threat closer. Minting ceased abruptly about 250 and buildings begun in happier times remained unfinished. The great pediment (Pl. 100) appears never to have been erected.

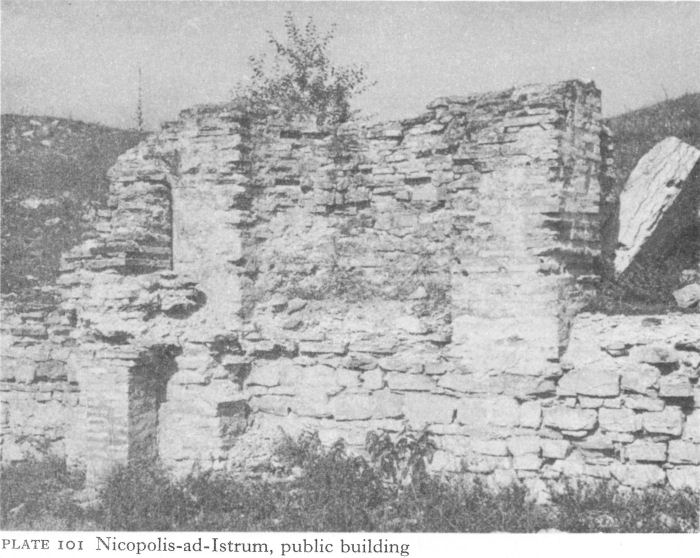

The peace along the limes imposed by Galerius and Constantine was a welcome respite; it could not revive the prosperity of the past, but a certain degree of recovery about this time is indicated by the erection of a brick and stone building occupying a large area, beginning 16 metres inside the north wall near the cardo maximus (Pl. 101). The plan, the evidence of hypocausts, and the debris of toilet articles, lamps, and glass vessels which littered one of the rooms suggest a public bath.

About 346, Bishop Ulfilas and his Visigothic Christian followers were given sanctuary and settled peacefully in the neighbourhood of Nicopolis. The Visigothic invaders of 376-82 were another matter. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, the fortified cities held out, but the countryside was devastated and depopulated. For a city so dependent on commerce, the effect on its economy must have been disastrous, even if the majority of its inhabitants survived to come to terms with the new, largely Gothic rural population.

Hotnitsa

Excavations at Hotnitsa, some 10 kilometres south of Nicopolis, show that besides being the main quarry for the city, it was an important centre for the manufacture of pottery and was probably an emporium. By 1969, 17 kilns were located, and finds of bronze statuettes and other objects reflect its share in the second- and early third-century prosperity.

Butovo

Even more important for ceramic production was present-day Butovo. Situated on the original border between Thracia and Moesia and on or near the Nicopolis-Novae and Nicopolis-Melta highways, Butovo was also the site of an important emporium, probably to be identified with Emporium Piretensium. Founded in the second century as a fortified trading post, the remains of defence walls, foundations of large buildings, and existence of re-used architectural fragments are evidence of a prosperous evolution. Successful trading and the excellence of the local clay led to the creation of production industries. Both stonemasons’ and potters’ quarters have been excavated. This development seems either to have been instigated by or to have attracted immigrant potters from Asia Minor, who, working alongside Thracian craftsmen, were able to turn out pottery with decorative motifs produced nowhere else in Bulgaria, although some influence appears in the Hotnitsa work. By the end of the second century imports were almost entirely superseded and Butovo factories were supplying both Novae and Nicopolis.

There were four main decorative techniques: barbotine, stamped impressions, incised drawing, and the application of clay relief figurines to a soft clay surface.

![]()

150

Plate 100 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, pediment

Plate 101 Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, public building

![]()

151

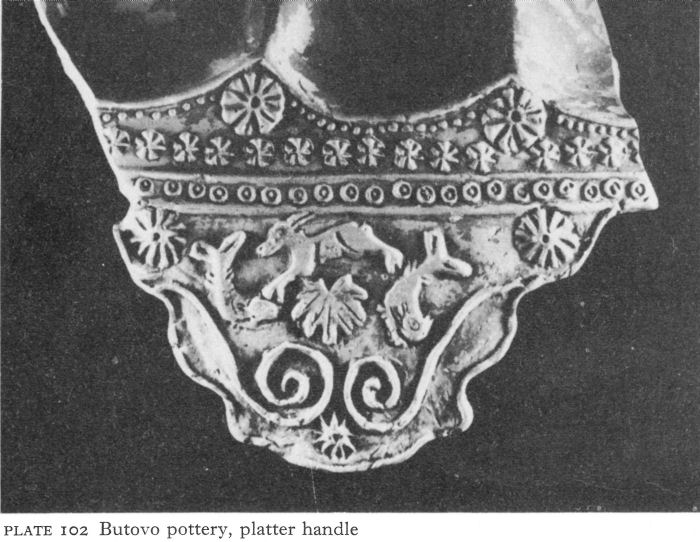

Plate 102 Butovo pottery, platter handle

Numerous moulds were found, and bowls, plates, and lamps, their surfaces crammed with naturalistic plant and animal ornament interspersed with geometric and various stylised designs (Pl. 102). Children’s toys - miniature clay horses, goats, cocks - and figurines were found in the debris, as well as votive tablets, including one of Orpheus surrounded by the wild beasts.

Butovo’s fate after the middle of the third century is unknown. Perhaps damaged or evacuated in the first Gothic invasions, some commercial advantages may also have been lost as a result of Aureban’s and Diocletian’s administrative changes. Few of the finds yet brought to light are likely to be post-third century.

Discoduratera

Discoduratera (Gostilitsa) lies on the upper reaches of the Yantra, 32 kilometres south-west of Nicopolis-ad-Istrum and about 16 kilometres north of modern Gabrovo. It was founded, probably about the middle of the second century, as an emporium of the territory of Augusta Trajana and stood at the junction of the highway from this city over the Shipka pass to Novae and a road from Nicopolis and Hotnitsa. Less exposed than Butovo, Discoduratera escaped the first Gothic invasions, although it was probably badly damaged in the last quarter of the fourth century. The surviving fortifications belong to the endfourth to sixth centuries.

There is no evidence of auxiliary industries, as at Butovo, but the emporium was a convenient overnight halt before or after crossing the Stara Planina. An inscription proves its existence in the reign of Marcus Aurelius, although it may have been settled earlier.

![]()

152

Fig. 28 Prisovo, villa rustica

Except for a few coins from local mints, the earliest found were silver of the first half of the third century; they were the only silver ones - from the mid-third century onwards all were copper. Bronze or copper coins of Nicopolis, Marcianopolis, and Pautalia (Kyustendil) occurred at the mid-third-century building level, all minted under Septimius Severus and Caracalla but evidently brought again into circulation by a currency crisis due to Gothic disruption of the local economy.

Above, more coins were found, dating to the reign of Aurelian, and his successors continued to be relatively well represented until the reign of Jovian. With renewed Gothic invasions came another gap - until Theodosius I - from which only a few coins of the Western emperors Gratian and Valentinian II have been found. Thus the pattern of coin finds reflects the effect of the invasions on the local economy; doubtless greater care was taken in hard times.

Although Nicopolis and its territory were transferred to Moesia about the end of the second century, an inscription shows that Discoduratera remained under Augusta Trajana, probably until the reign of Aurelian when it, too, came under the administration of Nicopolis.

Inscriptions and coins have yielded most information about Discoduratera, but a building of the third or fourth century excavated in the north-east part of the walled settlement has also produced items of interest.

![]()

153

It consisted of an L-shaped group of rooms enclosing in its angle a peristyled courtyard and with two small rooms projecting on the south-west side (Fig. 61). The monolithic columns were 2.15 metres high, carved from limestone, like their bases and Ionic capitals. This building did not outlast the fourth century. Soundings showed that earlier Roman structures lay below; and re-used materials in Early Byzantine constructions included dressed stone and even parts of bronze statues. Among secondand third-century debris near the gateway were votive plaques to Zeus and Artemis and bronze statuettes of Dionysos and Herakles, as well as fragments of good-quality pottery.

Prisovo

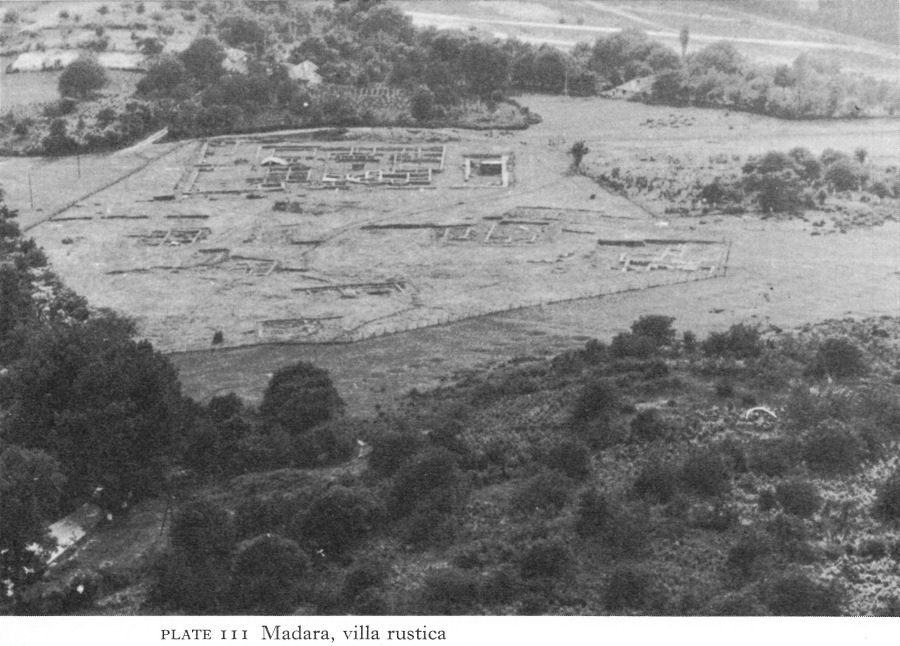

A modest villa rustic a, here a farmhouse not a manor, at Prisovo, near Turnovo, gives some idea of the life of a working farmer as distinct from that of a wealthy landowner. On a hill near a small tributary of the Yantra, the site remained unknown beneath trees and scrub until mechanical ploughing made it agriculturally viable. Following the discovery of archaeological material, thanks to a watchful local schoolmaster, a rescue dig took place in 1961.

Stone foundations were found of a rectangular building, 22 1/2 by 24 metres (Fig. 28). It had been a single-storeyed wooden structure, fastened with iron nails and then plastered with clay that, baked in the fire in which the villa perished, retained the imprint of the beams. The roof was tiled. In the southwest corner, finds of Thracian ceramic and a coin of Alexander confirmed other evidence of an earlier Thracian settlement.

Rooms of various sizes were grouped round a central courtyard; in several cases, objects found in situ indicated their purpose. On the south, the largest room, divided by a stone wall from the courtyard, served as a kind of barn; it contained iron agricultural implements and harness ornaments, such as two bronze bells. There was a doorway in the south wall and another, 1 1/2 metres wide, in a wood and mud-brick wall at its western end. An iron-bound wooden door led from the corner room to the next along the west side; both these had traces of plaster decoration in red, black, and white, the only rooms so ornamented. The many finds, chiefly of pots, suggested that the neighbouring small, narrow room was a storeroom. In the next along the west side, square brick paving on a mortared foundation was found on top of clay hypocaust pipes.

On the north side, a narrow corridor separated the north-west corner room and its neighbour, between which and the north-east corner room, with a doorway in the east wall, was a portico, shown by the remains of wooden beams from the eaves and of two wooden pillars, the base of one of which remained. Another long rectangular room, of undetermined use, occupied the middle of the east wall. It is considered that the roof sloped towards the inner courtyard and projected sufficiently to provide a rustic peristyle borne on wooden columns. There were probably other farm buildings in the vicinity. A lime pit was found about 9 metres north of the villa and 75 metres north a well, whence no doubt water was fetched in a bucket of which the iron handle was found.

There was a great deal of pottery, all wheel-made but clearly divided into rough kitchenware and finer vessels. The source of some of the latter, including lamps and other vessels with relief and incised decoration, was probably Butovo and dated to the first half of the third century. The owner possessed such items

![]()

154

as bone spoons and a comb, as well as a useful collection of iron farm implements with whetstones and other accessories. The only luxury object found, if one excepts some of the finer ceramic, was a tiny glass gem engraved with a single-masted ship in full sail. It is easy to imagine that the farm belonged to a Thracian veteran of the Roman navy.

No inscriptions were found and the 17 Roman coins (seven of them minted in Nicopolis-ad-Istrum and Marcianopolis) were issues ranging from Commodus to Ottalicia, wife of Philip the Arab. The excavator dates the villa to the end of the second or the beginning of the third century. Razed in a fierce conflagration, there can be little doubt that this modest farmhouse was one of many similar victims of the mid-third-century Gothic terror.

II. MARCIANOPOLIS

In north-east Bulgaria the largest and most important city was Marcianopolis (Reka Devnya), founded by Trajan just within the borders of Thracia and named after his sister Marciana. Situated on the Devnya springs less than 30 kilometres from Odessos, which remained in Moesia, the new foundation demonstrated the emperor’s reluctance to increase the power of the old, essentially Greek city; although he probably disliked but found it impolitic to destroy its autonomy.

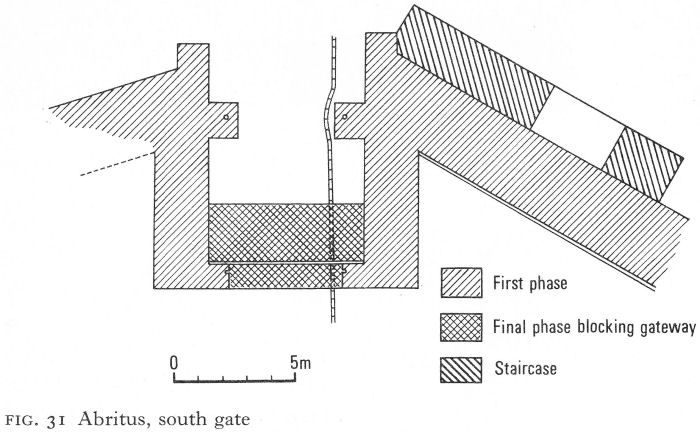

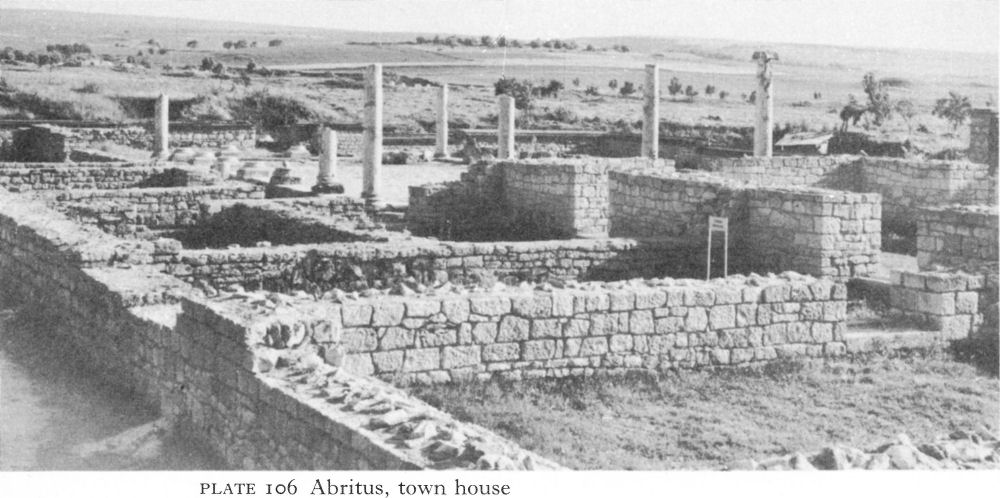

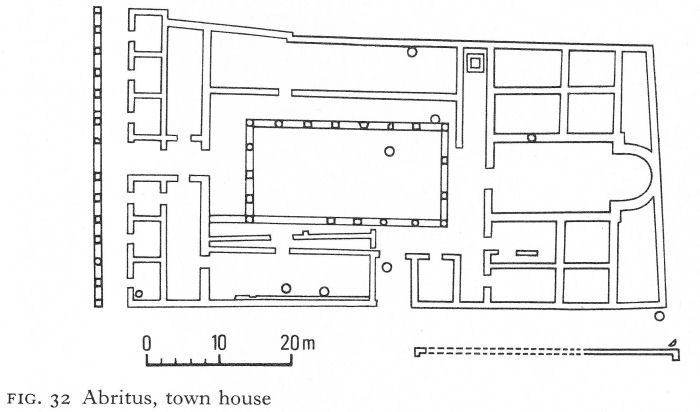

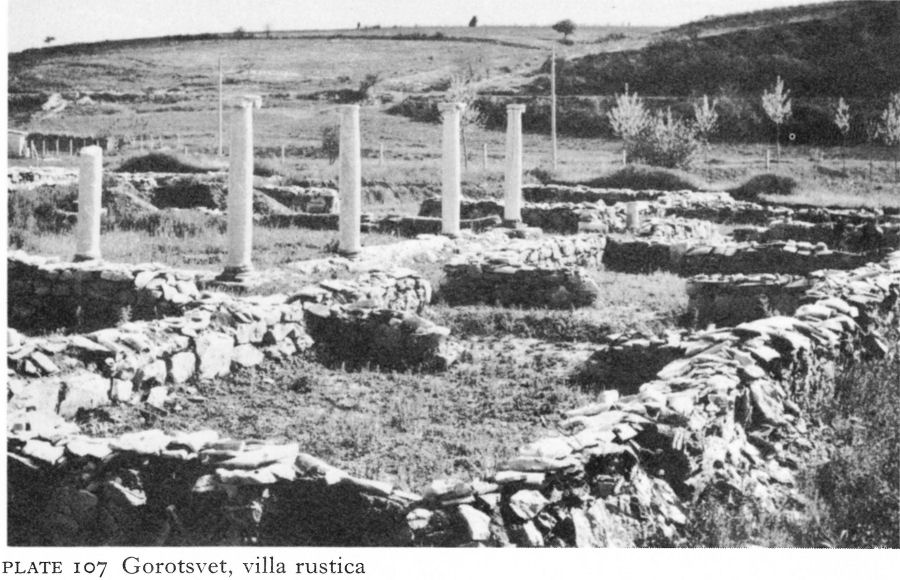

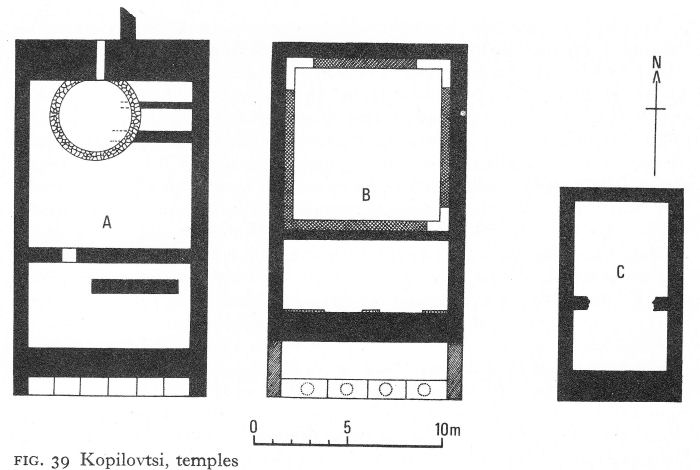

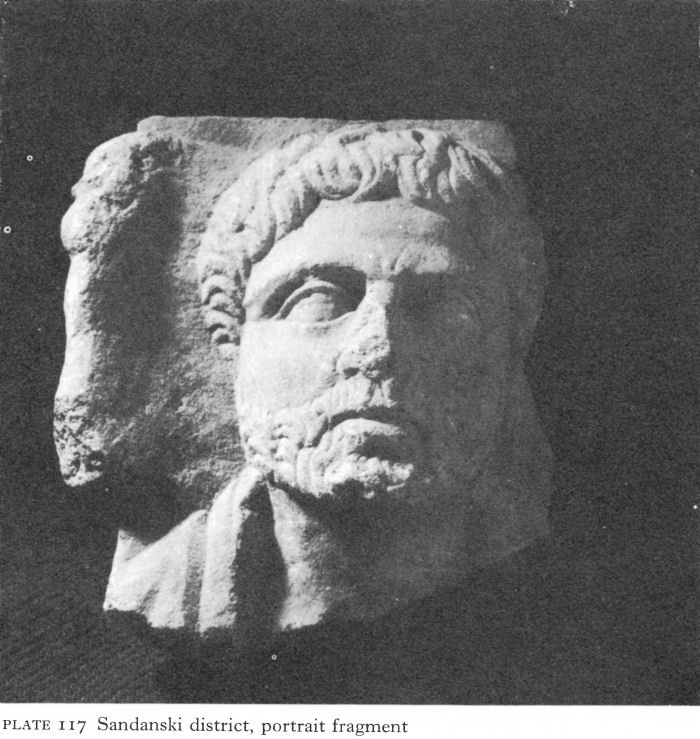

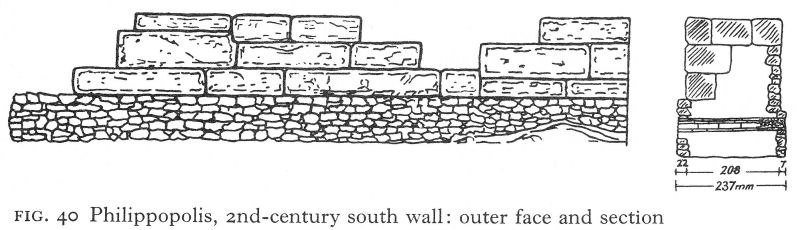

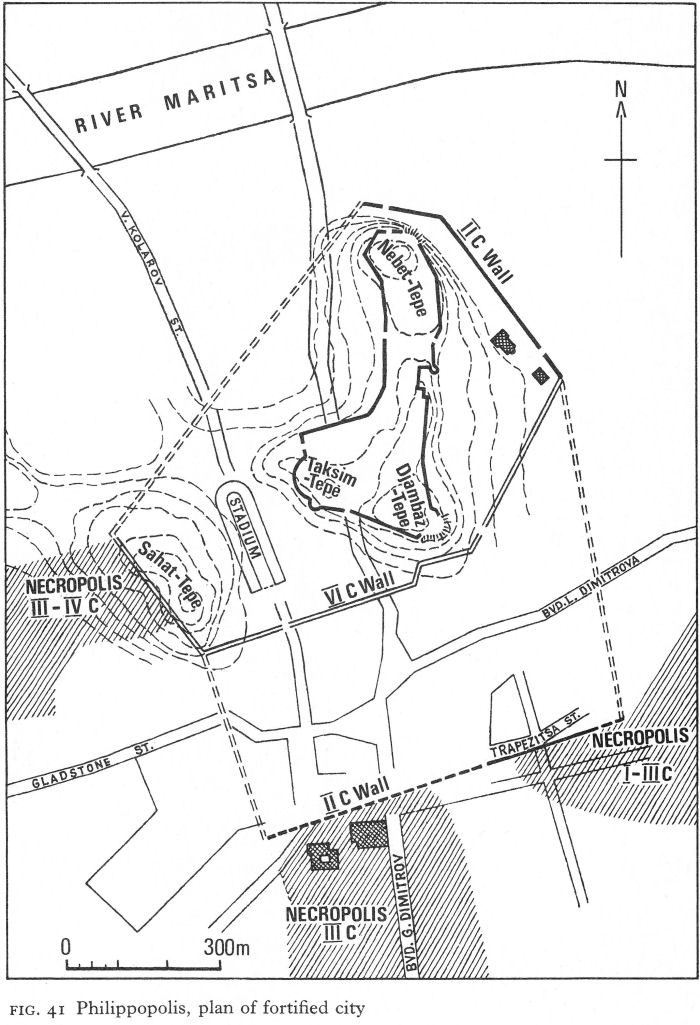

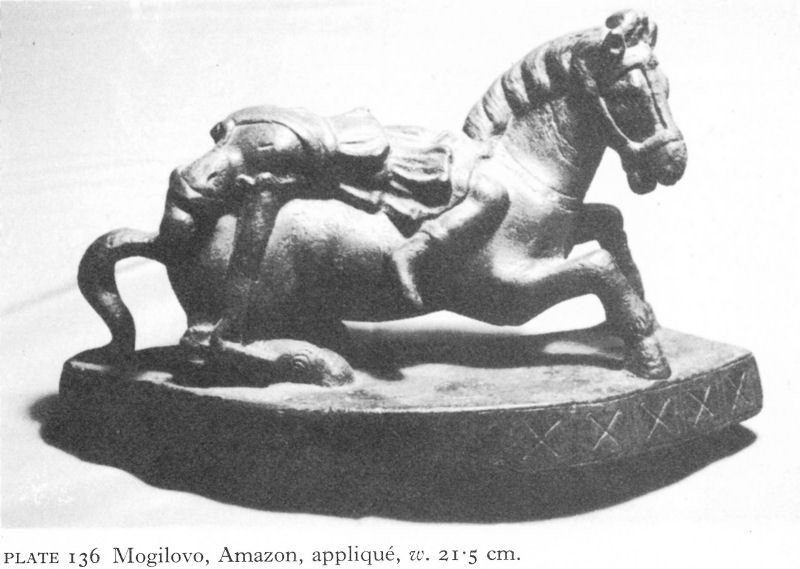

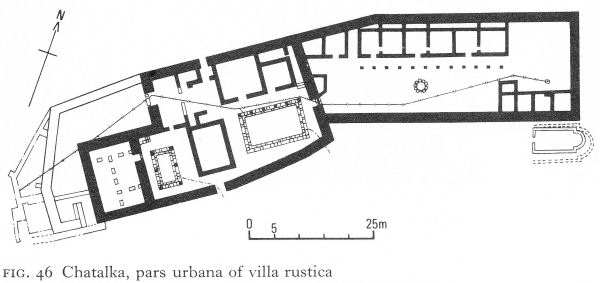

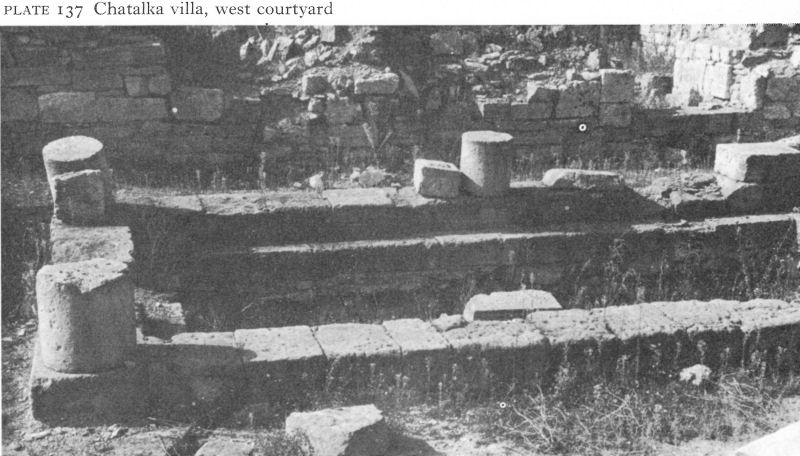

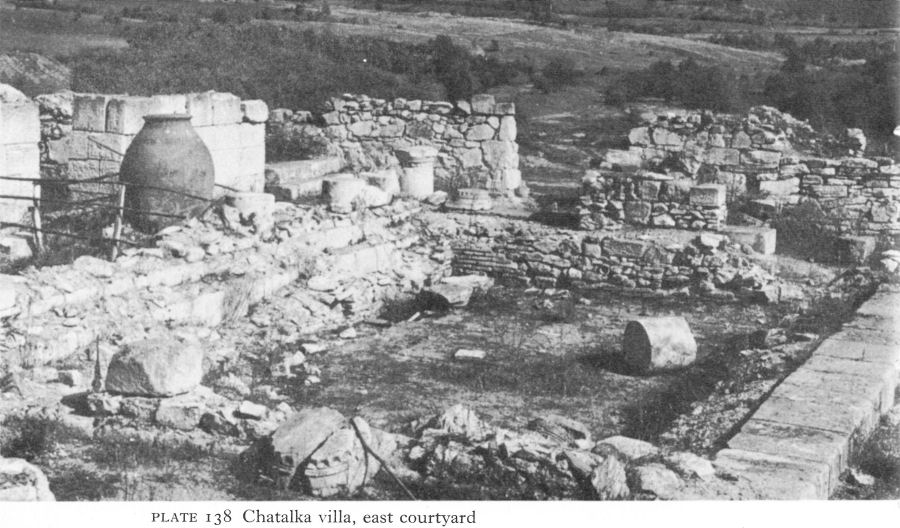

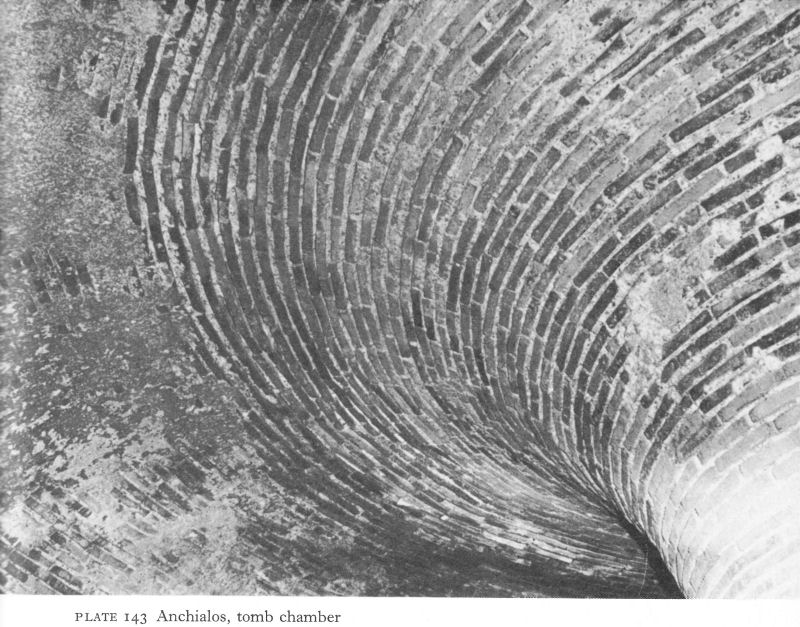

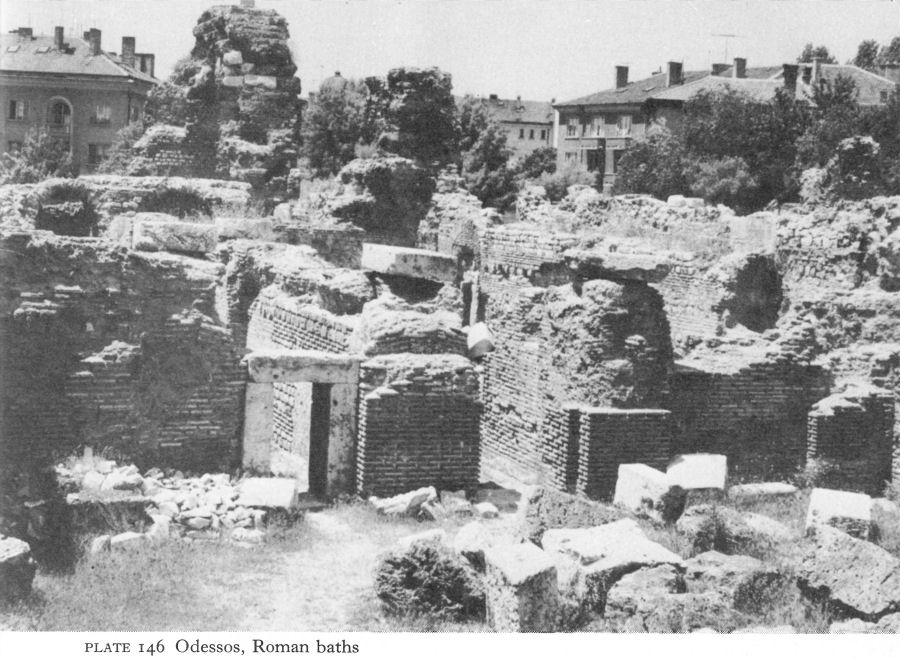

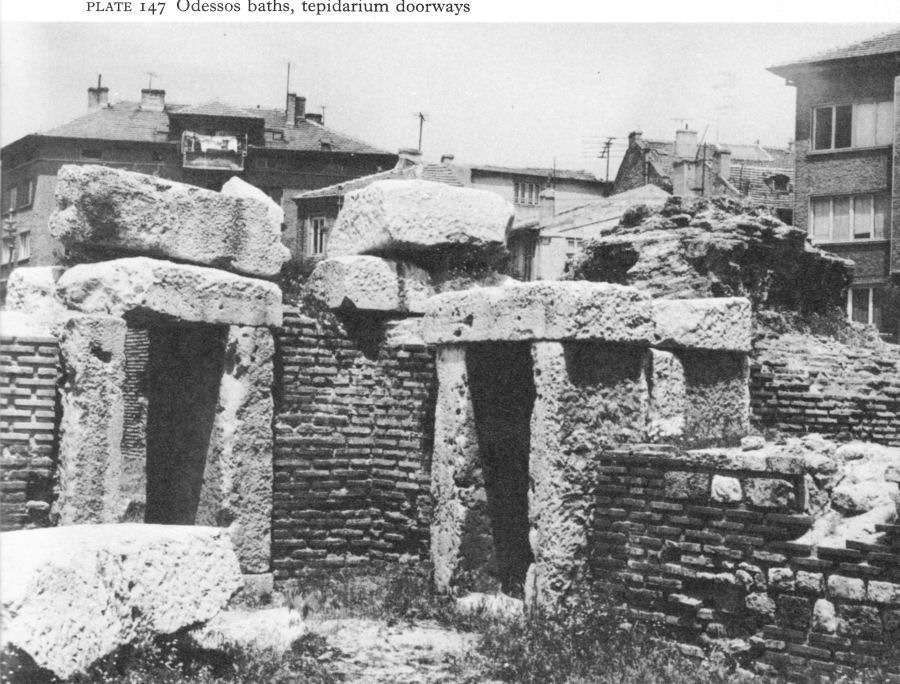

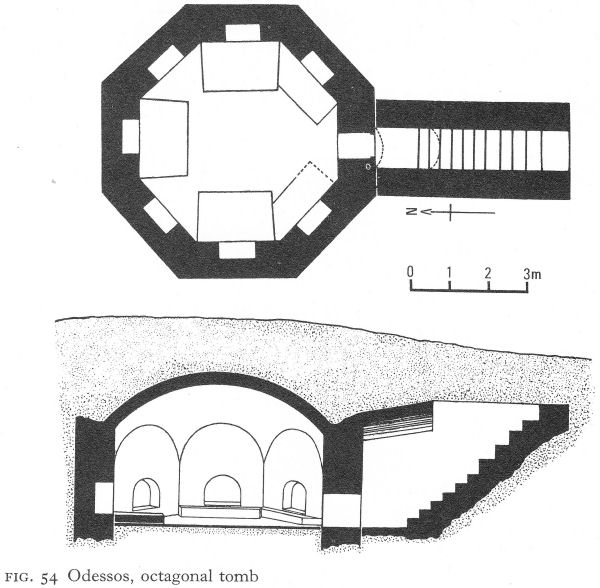

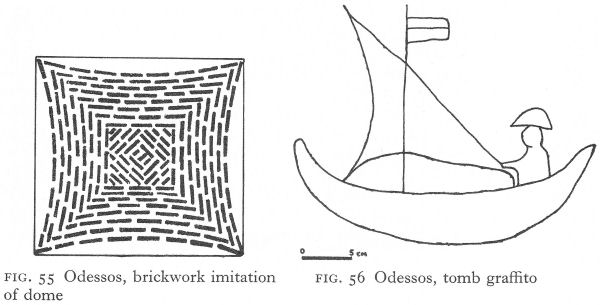

Marcianopolis was a strategic communications centre - the convergence of a road network running from the lower reaches of the Danube and the Dobroudja, crossing the Stara Planina to the south, and coming eastwards from Melta via Nicopolis-ad-Istrum to reach the Black Sea at Odessos. The little existing evidence suggests that Marcianopolis, like Nicopolis, was organised on the pattern of a Hellenistic city, with many settlers of Greek, especially east Greek, origin, its Hellenistic character strengthened by contact with the coastal colonies. As one city served as a rear headquarters for Novae, so did the other for Durostorum. The fortified area is estimated at about 70 hectares, whilst Odessos, no mean city, had only 43 hectares. Like other cities, Marcianopolis reached a peak of prosperity under the Severi, when it was transferred from Thracia to become the capital of Moesia Inferior.