III. BETWEEN THE FRANKISH AND BYZANTINE EMPIRES AND THE NOMADS

1. The Slavs and the Nomad Tribes 53

2. The Pressure of the Great Powers and the First Organized States 66

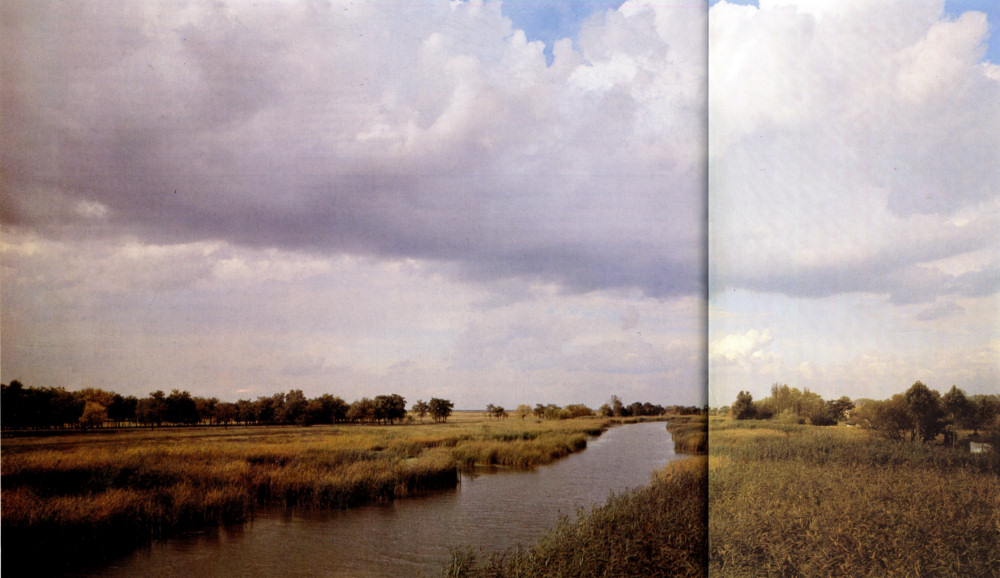

The waves of nomad tribes usually came to a stop in the Carpathian Basin where in the valley of the river Tisza they set up a base suitable for further looting and raiding.

1. THE SLAVS AND THE NOMAD TRIBES

The broad steppes stretching from the heart of Asia to Eastern Europe and in places as far as the Elbe, the Danube region and the Carpathian Basin have, since time immemorial, served as open spaces for migrating nomads, who from time to time spread like flooding waves in one and the same direction: from east to west. In antiquity there were the Iranian Scythians and Sarmatians, later mainly the Turco-Tatars and Mongolian tribes, in the fourth century the Huns, followed in the sixth century by the Avars, in the seventh by the Bulgars, and towards the end of the ninth by the Magyars (who settled in Hungary). Mongolian raids in the thirteenth century proved a major disaster. All these raiders had one thing in common: they occupied a vast territory for a certain time and founded their large and feared empires there. But none of them lasted long, since the militarily stronger, but otherwise small numbers of unproductive nomads, backward economically and culturally, were soon absorbed by the local population. Only the Magyars kept themselves apart as a unit and survived as a nation and a state up to the present time thanks to having adapted resiliently to European culture. The Bulgars left no more than a name behind — which came to be applied to the Slav tribes with whom they merged.

The oldest migration — that of the Scythians and the Sarmatians — took place at a time when the existence of the Slavs cannot be proved historically or by archeology. Only the Hun raids took place at the time of the Slav ethnogenesis when mutual relations might have been established.

The Huns belong to the militant Turkic tribes, who lived in Central Asia, east of Lake Baykal. From there they raided the frontiers of China not far away. In the first centuries A.D. some of the Huns set out on a westward march: around the year 370 they crossed the Don, and some five years later they destroyed the empire of the Germanic Goths in the Ukraine. The retreat of the Visigoths and Ostrogoths in the face of Hun pressure as far as the Roman provinces began the great migration of peoples on the European continent. Among others, this caused the fall of the western part of the Roman Empire. In the early fifth century the Huns penetrated into Pannonia, which, in the first half of the century, became

52-53

![]()

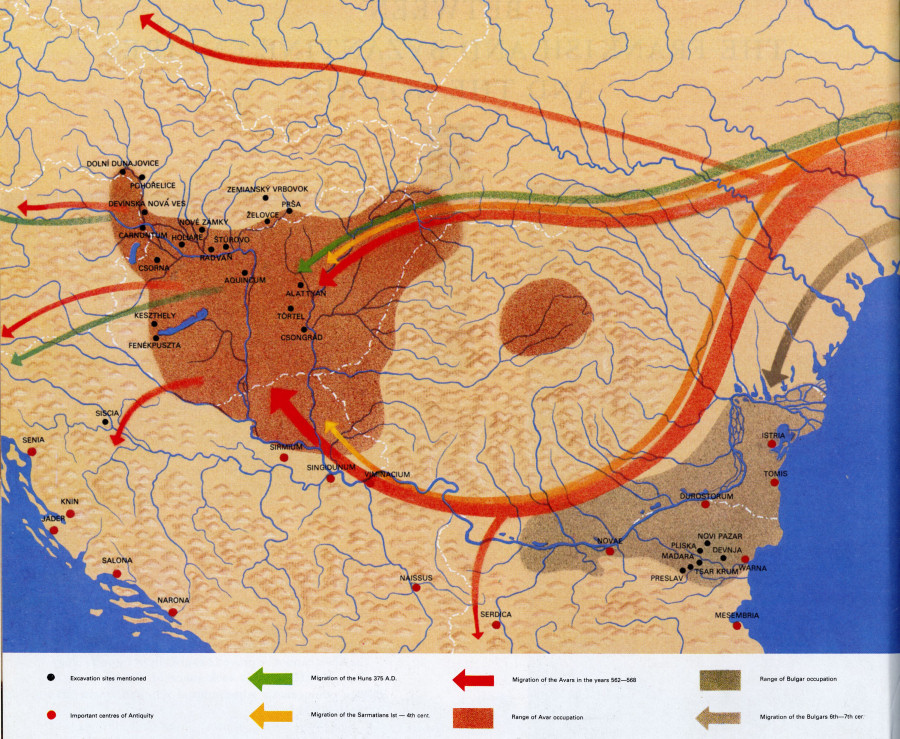

[[ Excavation sites mentioned; Important centres of Antiquity; Migration of the Huns 375 A.D.; Migration of the Sarmatians 1st — 4th cent.; Migration of the Avars in the years 562—568; Range of Avar occupation; Range of Bulgar occupation; Migration of the Bulgars 6th—7th cent. ]]

The steppes in the plains of south-eastern Europe had always been the domain of nomad tribes, who had come from the heart of Asia as far as the Carpathian Basin and the lower reaches of the Danube. The migrations of the Sarmatians, Huns, Avars, Bulgars and other militant nomads basically followed the same direction.

their base for far-reaching expeditions both to the Balkan peninsula against Byzantium and westward to Gaul and Italy. In Gaul they suffered defeat on the Catalaunian Plains near Troyes in the year 451, but only one year later they very nearly conquered Rome; this disaster was prevented only by the skilful diplomacy of Pope Leo I. The Hun empire was doomed after the death of its remarkable leader Attila in 453. The Huns were finally scattered during a successful uprising of the subjected Germanic tribes in 455. The long years of bloody battles between the Germans and the Huns are reflected, among others, in the famous epic The Song of the Nibelungs.

The archeologists have found proof of the presence of Huns in the Ukraine and in Central Europe on burial grounds where they found typical graves of people of a Mongoloid type with deformed skulls. This special fashion of deforming the skulls of children to an excessively elongated shape was common among the Huns and some of their Germanic contemporaries,

54

![]()

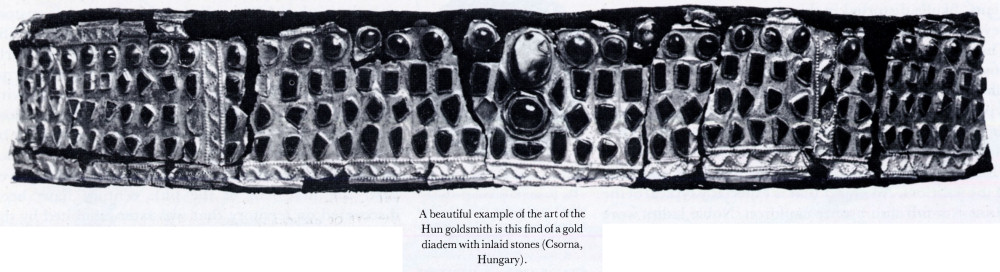

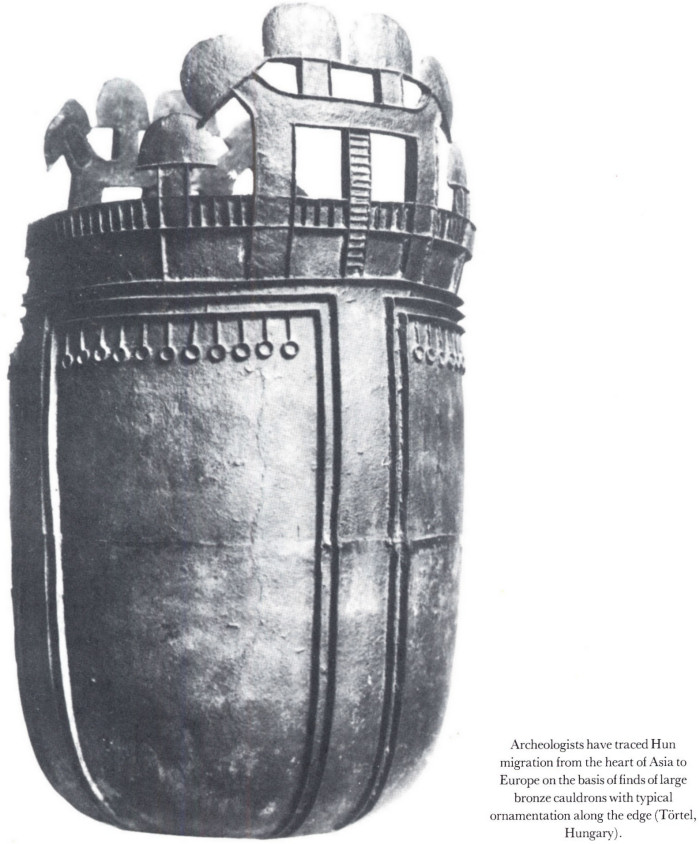

especially the Lombards, Thuringians and Burgundians. Skulls distorted in this manner can be also found beyond the reach of Hun rule — in Bohemia, Moravia, Thuringia and along the Rhineland. The Hun graves, however, differ from the Germanic ones by their offerings, mainly weapons, in which the bow of eastern type with three-edged arrow-heads, double-bladed and short single-bladed swords played a major role. They further included richly adorned saddles with gold or silver mountings, similarly ornamented reins and belts of the warriors. An object that is especially typical of the Huns is a tall slim bronze cauldron. Noble ladies wore gold diadems and used bronze mirrors, as did the Chinese.

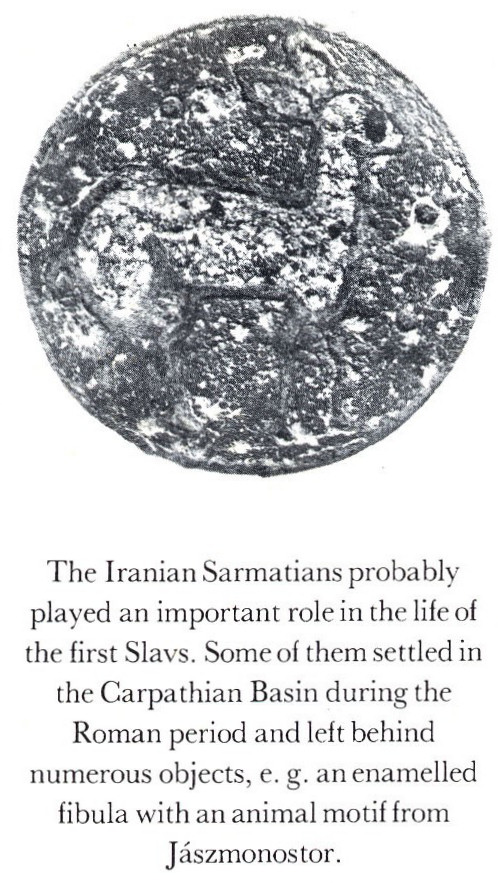

The Iranian Sarmatians probably played an important role in the life of the first Slavs. Some of them settled in the Carpathian Basin during the Roman period and left behind numerous objects, e. g. an enamelled fibula with an animal motif from Jászmonostor.

Sarmatian pottery had elegant shapes as shown in this mixture of the local tradition and Eastern elements (Csongrád, Hungary).

The relations between the Huns and the Slavs remain unclear. Usually it is pointed out in this connection that the Huns fought a battle against the Antes in the Ukraine in the third quarter of the fourth century. As we showed above, at that time the Antes must still have been an Iranian tribe, who adapted to Slav ways only at the end of the fifth and in the early sixth century. Two other historical data have likewise not been confirmed. When in 448 messengers from Theodosius II arrived at Attila's court in Pannonia, his historian Priscus recorded that the messengers were given drinks called medos and kamos. The first can be identified with mead, a favourite drink of the ancient Slavs, and the second with a name that is definitely not Slavonic, referring to some form of beer made of barley. The Goth historian Jordanes, among others, reveals that a banquet was held over the tomb of Attila, called strava, which was a custom and a name given to a similar ceremony among the Slavs. Both medos and strava are, however, similarly recorded among the Germanic tribes as the two terms can be derived from the language of the Goths with whom the Huns were in historically proven close contact. So that this information cannot necessarily be associated exclusively with the Slavs. Nor does archeology provide a clear picture on this matter. Hun graves from the first half of the fifth century have been discovered on territory that was later inhabited by the Slavs, e.g. in southern Poland, without any further proof that a Slav population lived there already at that time.

While nothing definite can be said about the relations between Slavs and Huns, we are on much safer ground in relation to other eastern nomads — the Avars, who had a far-reaching effect on the life of the Slavs in the Danube region. Archeologists even speak of a Slavo-Avar cultural period; this refers to a period in the seventh to eighth century when characteristic features show a symbiosis of the two ethnical units on the territory of present-day Hungary and neighbouring regions, including south-west Slovakia. It was primarily an economic symbiosis, for from the beginning the Slavs tilled the land while the Avars were nomad pastoralists who lived by cattle breeding and looting. It was, in addition, a political symbiosis in which the Slavs played a varying role from voluntary allies to tribute payers,

55

![]()

dependent and even serving and exploited tribes. It was even a cultural symbiosis, in which the Slav population, chiefly its nobility, adapted to some extent to the ways of the nomads, especially in dress and certain customs. But they represented a more creative element than the looting nomads, who only amassed objects of value but did not create them. This side of things was entirely overlooked in the past, and therefore literature speaks only of an Avar culture without paying regard to its Slavic component.

A beautiful example of the art of the Hun goldsmith is this find of a gold diadem with inlaid stones (Csorna, Hungary).

The origin of the Avars is wrapped in mystery. Historians have been leading disputes as to whether they were of partly Mongolian, or Turco-Tatar race, whether they belonged to a Central Asian tribal unit whom the Chinese knew as Juan-Juan in the sixth century, or whether they were related to the Hephthalites, known as the White Huns. The last view could be upheld by the names of two Avar tribes — the Uar and the Chunni, recorded in Byzantine sources and in the Caucasian region through which the Avars moved as they advanced towards the west. According to historian Priscus they came there as nomads in the fifth century, appeared, around the year 558, in the steppes to the north of the Sea of Azov and then quickly moved across the territory of the Eastern Slav tribes to the west. In the years 561 to 562 they passed the Carpathian and Sudeten mountains to attack Thuringia, which then belonged to the Frankish Empire, but were driven back. A second attack in the years 566—567 was more successful, since they managed to take King Sigebert prisoner. In the meantime they reached the lower Danube region and moved upstream from there and through the passes in the Carpathians to the middle courses of the Danube and Tisza, where, together with the Lombards, they defeated the Germanic Gepids. They then settled on their territory between the Danube and the Tisza. That was where they had their main hring — probably a fortified camp. When in 568 the Lombards moved on to northern Italy, the Avars also took over the region to the west of the Danube — Pannonia. In that way an extensive Avar Empire came into being, which stretched from western Hungary and Slovakia as far as the southern Ukraine and was a major threat to the two great powers of the time — the Frankish Empire in the West and Byzantium in the East.

The lucky star of the Avars set relatively soon, in the first quarter of the seventh century. They received the first blow from the Central European Slavs, who staged a successful uprising under Samo some time in 623—624. At the same time the Croats and Serbs in the south liberated themselves, and in 626 a major disaster occurred in the form of a defeat outside Constantinople. Under the leadership of Kuvrat the Bulgarian tribes of the Kutrigurs and Utigurs split off from the Avars, having until that time belonged to the union of Avar tribes. So gradually the rule of the Avars, limited to the territory of present-day Hungary, fell apart. The fatal blow was struck by Charlemagne in the years 791—799, and the Bulgarian Khan Krum overwhelmed the Avars from the south. From that time on nothing more was heard of them and they vanished completely in the ninth century.

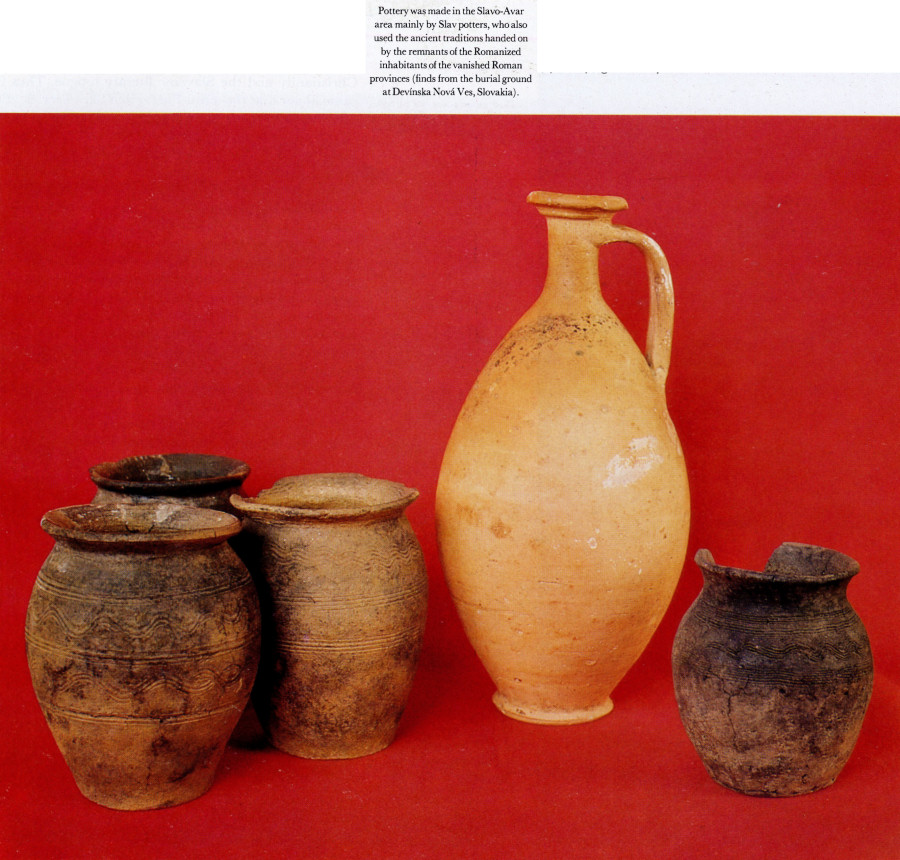

When the Avars reached the Hungarian Plains, they were a great mixture of tribes associated in a tribal union. Their core was formed by two tümens of Avars proper, roughly 20,000 people. The second strongest component were the Bulgarian Kutrigurs and Utigurs, the rest smaller tribal groups. These tribes were only loosely related and came under the central power of the Khans only during military campaigns. Apart from these, the Avar community included other ethnic groups, in the first place the Slavs, with whom the Avars had come into contact in their advance towards the west and had taken along to the Carpathian Basin. This gave some scholars the mistaken idea that the entire Slav settlement of Central and Southern Europe was, in fact, due to the Avars. In reality their merit is but secondary or indirect: some tribes came with them as allies, others retreated before them, e.g. the Volhynian Dulebi, groups of whom scattered across Central and Southern Europe after being defeated by the Avars even before the latter reached these regions. Apart from the Slavs the Carpathian Basin was peopled also by remnants of Germanic and Iranian tribes (Sarmatians) and certain sections of the Romanized population, especially in the former province of Pannonia. This has been proved by finds at Fenékpuszta near Lake Balaton, which can probably be identified with the Roman Mogentiana. The presence of the sparse but culturally advanced population of the Roman provinces — so attractive to conquerors — explains the survival of certain ancient traditions in the goldsmith, blacksmith and pottery

56

![]()

trades at the time of the Avars and later during the period of the Great Moravian Empire.

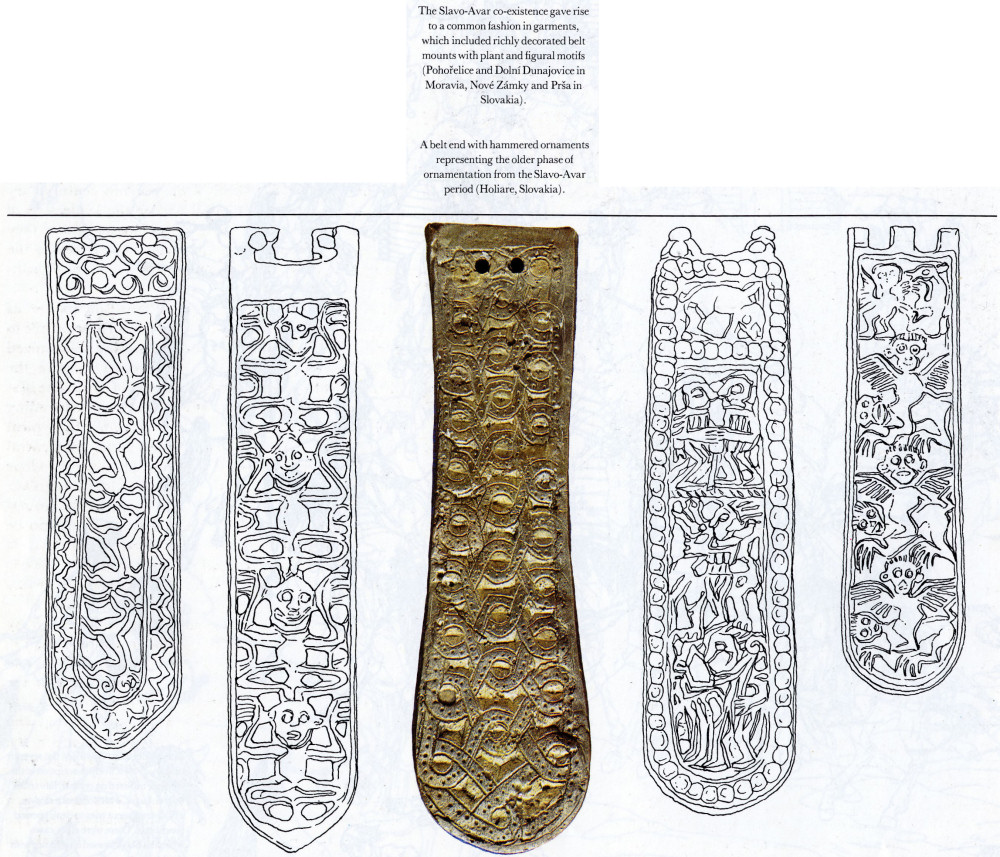

The history of the Avars still contains a good deal that has never been explained, for written records about them are but fragmentary and lend themselves to different interpretations. The relatively rich archeological finds both in the Avar territory proper and in neighbouring areas, where Avar influence was strong, are a welcome aid in the search for answers to many of these questions. Finds in graves run into tens of thousands. Here the archeologists distinguish two phases: typical of the older, which covers the sixth and a large part of the seventh century, are ornaments of repousse gold, silver or bronze plate, while the later graves from the end of the seventh to the end of the eighth century contained cast ornaments of a different style, often in rich settings.

Archeologists have traced Hun migration from the heart of Asia to Europe on the basis of finds of large bronze cauldrons with typical ornamentation along the edge (Törtel, Hungary).

In both cases these ornaments were applied to belts, richly adorned with mounts, attached even to short hip bands. At one end of the belt was a tongue-shaped strap-end, which was threaded through the buckle at the other end. In the older period the metal mounts were of a variety of shapes: circular, trefoil, lozenge-shaped, escutcheon-like, horseshoe, heart or shield shaped. They were adorned with pearl, lily, trellis or plaited patterns, coloured glass, etc. Far more numerous are the cast mounts of the later period, the seventh and eighth centuries. They include sarmentous, ramified, lily, palmette or trefoil shapes and animal motifs, especially griffins, those legendary beasts of ancient mythology with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle, known in the art of antiquity and the Orient. Apart from these there appeared elements derived from ancient as well as Christian patterns.

The origin of these ornaments and the crafts which produced them is hotly debated by scholars. The older group shows Byzantine-Hellenistic influences which spread to the steppe cultures north of the Black Sea. The Avars came into contact with them during their advance to the west. Far less clear, however, are changes in fashion towards the end of the seventh century, represented by the group with cast bronze ornaments. Patterns for these are being sought in the East, even as far away as in Siberia, and this seems to be an indication that new nomads were arriving from the Kama river area. But there are no historical sources to confirm this. The eastern ornaments occur, moreover, only sporadically among the exceptionally numerous finds in the Carpathian Basin and therefore do not provide proof of their origin. It would seem that these artefacts were made on a large scale in local workshops, where metal-workers adapted influences from Byzantium and the nomads, from Christian art and from provincial tradition, Sassanid Iran and perhaps even from Coptic Egypt. What they produced represented a blend of these individual elements into a unified style, which basically suited the taste of nomads but must certainly have spread also among other ethnic groups in the Avar period — e.g. among the Slavs.

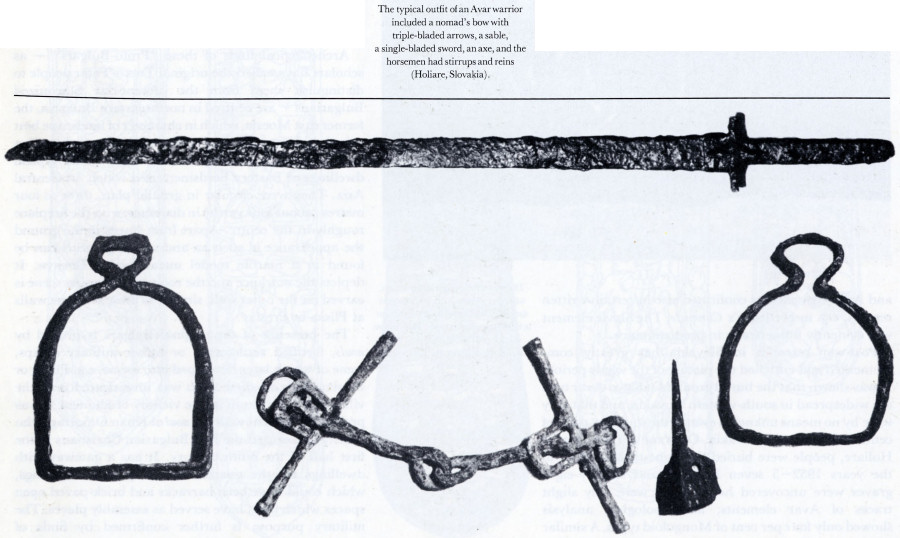

Apart from these objects of distinct style the archeologists have also found weapons and horse saddles and stirrups in the tombs. The Avars were excellent riders and owed their success on the battlefield mainly to fast attacks on horseback. As a result they were often buried with their fully saddled horses. They had typical circular ornaments, called phaleras, repoussé or cast, or stirrups, which, in fact, were an Avar invention. The weapons of the Avars were sabres, single-edged swords and bow with bone or horn parts, including triple-edged arrows. The Slavs, on the other hand, as allies of the Avars, fought on foot and their typical weapons include axes, lances, bows and cudgels. But even the Slavs had mounted troops. Their equipment included swords, lances, stirrups and spurs (with counterhooks) which were not used by the Avars, for in the Eastern manner they used little whips to urge on their horses.

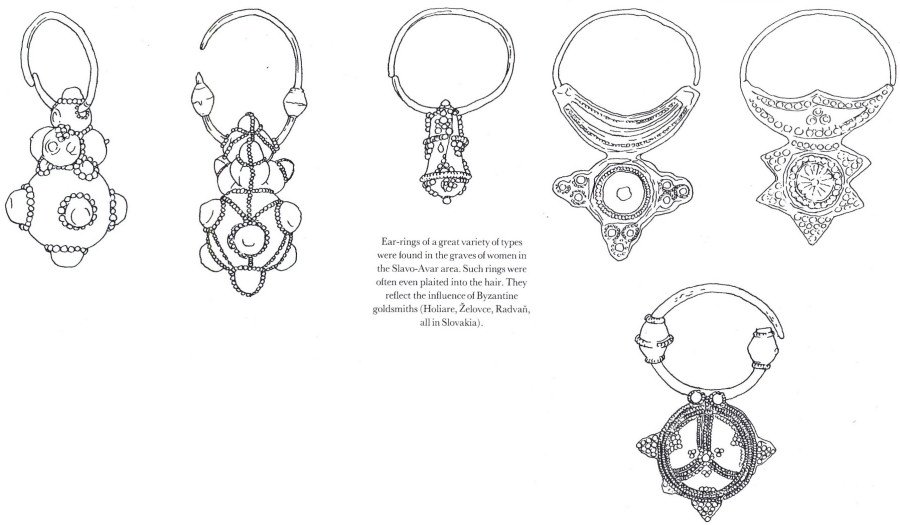

Women's graves held bronze, silver and even gold jewels, among them ear-rings of highly varied shapes,

57

![]()

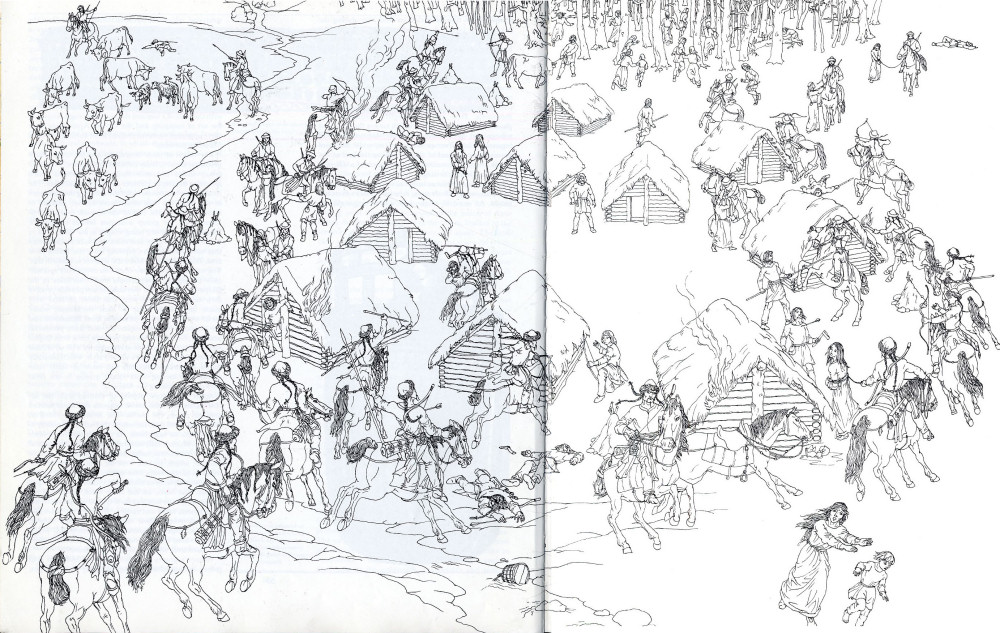

The Fredegar's Chronicle of the seventh century gives a lively description of the violence inflicted on certain Sav tribes by the Avars. This scene of a raid on a Slav settlement tries to depict period conditions. There were other cases when the Slavs formed an alliance with the Avars.

58-59

![]()

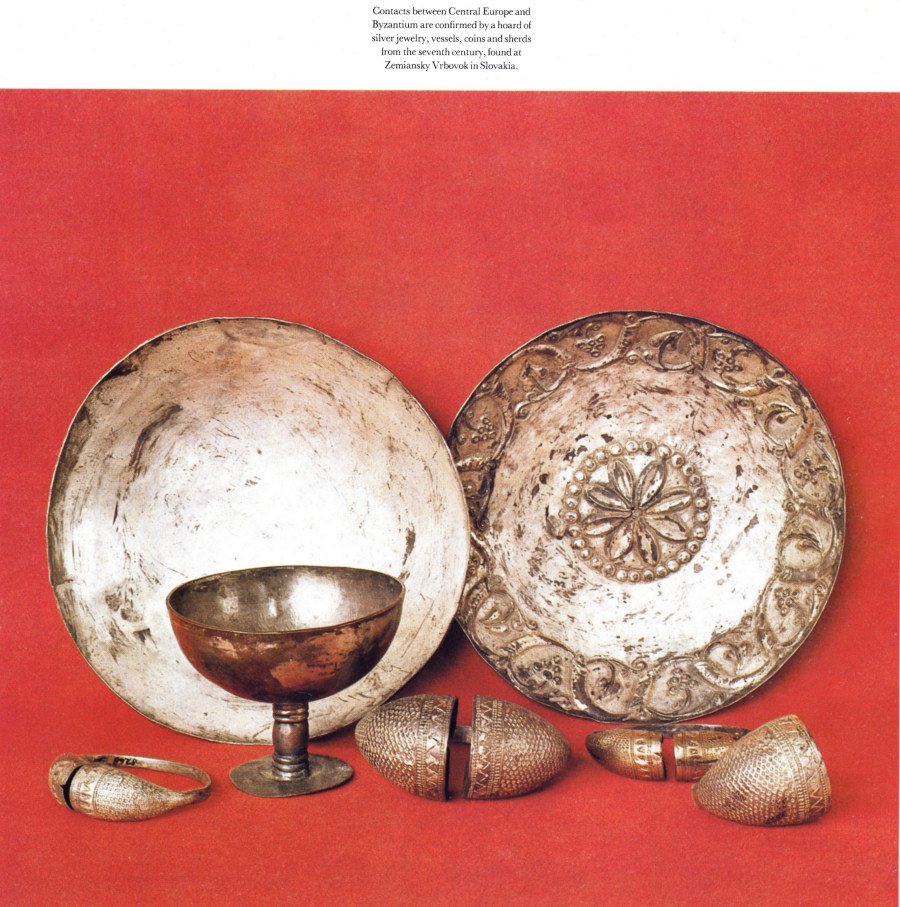

often twisted into the hair; in addition bracelets, rings, buckles and glass necklaces have been found. They show the predominant influence of Byzantine goldsmiths but were all made in local workshops, only a few precious pieces being imported. An example is a unique discovery of a silver treasure at Zemiansky Vrbovok near one of the main routes that linked Slovakia with the regions beyond the Carpathians.

Now let us take a look at typical Avar burial grounds which have been systematically examined by Hungarian and Slovak archeologists. Such burial grounds are the most important sources of information on the social structure and cultural level of the time.

The Slavo-Avar co-existence gave rise to a common fashion in garments, which included richly decorated belt mounts with plant and figural motifs (Pohořelice and Dolní Dunajovice in Moravia, Nové Zámky and Prsa in Slovakia).

A belt end with hammered ornaments representing the older phase of ornamentation from the Slavo-Avar period (Holiare, Slovakia).

Particularly valuable data were produced during excavations of the burial ground near the village of Alattyán in the Szolnok Comitatus in the years 1934 to 1938. A total of 711 graves were opened up, documenting the entire Avar period from their arrival to its very end. The dead were given their personal property to accompany them on their way to the after-life, even food as shown by bones of cattle, pigs, sheep, and fowl, eggshells as well as bowls with liquids. The offerings, burial rites and the location of the graves distinguish groups which followed one upon the other in time. Scholars link the two younger groups with the influx of a new population from the East, even though it is very difficult to make any ethnic attribution because even anthropological analysis does not always lead to unambiguous conclusions. The people who were buried at Alattyán are a mixture of Mediterranean, Nordic, Iranian, Pamir and Mongoloid types with the latter, who might have represented the Avars proper, forming only a small percentage. So it would seem that the Avars ruled over a very mixed tribal society formed both of Eastern and local elements.

The burial ground at Devínska Nová Ves, to the west of Bratislava, was excavated in the years 1926—33. It proved of basic importance in trying to solve the complex problem of cultural and ethnic adherence in the Slavo-Avar period. A total of 875 graves were unearthed, dating from the beginning of Slav settlement. In twenty-seven of these the bodies had been cremated; there were ninety-four riders, thirty-five foot soldiers, etc. The analysis of the finds and the burial rites led to the conclusion that the burial ground provided proof of the close co-existence, even the intermingling, of Slavic

60

![]()

and Avar elements, as confirmed also in certain written reports, e.g. in Fredegar's Chronicle. The Slavic element was evidently numerically in predominance.

The Avars were excellent horsemen, who were so close to their horses that they often had them buried with them in lull harness and armour. This custom was adopted by the Slavs who lived near them (Štúrovo, Slovakia, eighth century).

Post-war research in Slovakia has greatly complemented and enriched the picture of the whole period. It was shown that the burial grounds of Slavo-Avar type are widespread in south-western Slovakia, and that they were by no means unknown even in the southern parts of central and eastern Slovakia. On some of them, e.g. at Holiare, people were buried throughout the period; in the years 1952 — 5 seven hundred and seventy-eight graves were uncovered here. There were only slight traces of Avar elements; anthropological analysis showed only four per cent of Mongoloid types. A similar picture was derived at other burial grounds, e.g. at Štúrovo or Prša, where settlements with semi-subterranean dwellings were found, proof of a settled agricultural population such as the Slavs and not the nomad Avars.

The oldest phase from the end of the sixth and the first half of the seventh century was found in Slovakia only along the Danube, while burial grounds further to the north (e.g. at Nové Zámky) arose slightly later, after the middle of the seventh century.

In this manner archeological sources produce evidence of the strange symbiosis of the nomad cattle-grazers and the settled agricultural tribes in the Carpathian Basin in the sixth to eighth centuries, showing the economic, political and cultural co-existence of different ethnic groups. These grew into the settled Slav peasants and craftsmen led by their newly emerging nobility.

A similar conclusion was reached by the co-existence of the Balkan Slavs and the nomad Bulgars. The latter were tribes of Turco-Tatar origin, whose original home had been the region along the Volga, north of the Caspian Sea and the Sea of Azov. Some of these moved from there in the sixth century together with the Avars advancing across the Ukraine to the lower reaches of the Danube. In the last third of the seventh century they split off from the Avars and, under the leadership of Asparuch, penetrated to ancient Moesia where they formed an alliance with the local Slav tribes in the struggle against their common enemy — the Byzantines.

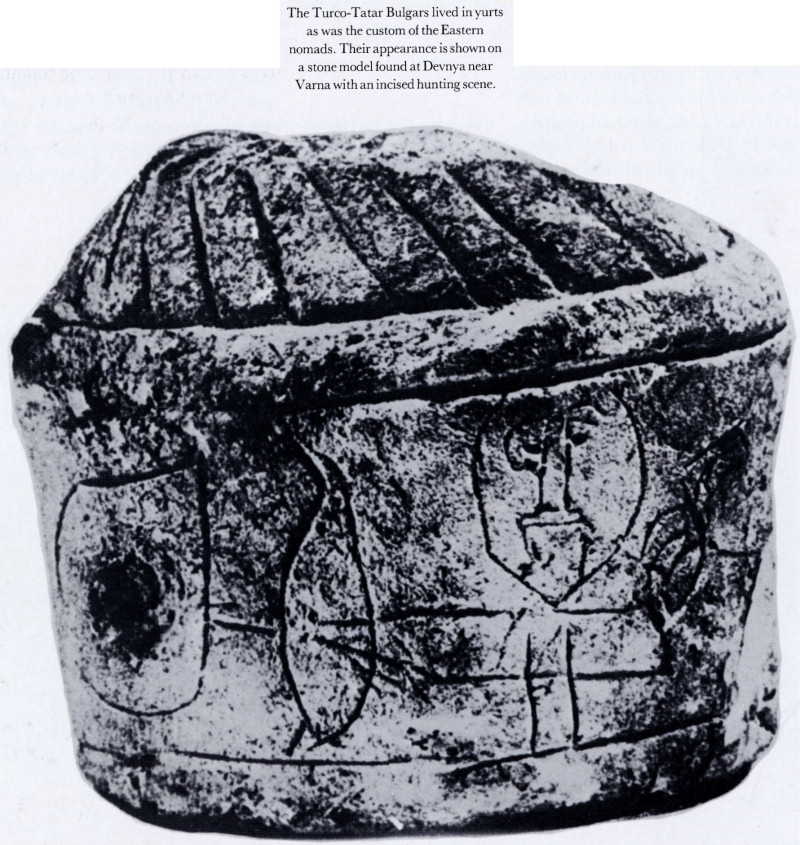

Archeological finds of these "Proto-Bulgars" — as scholars have called the original Turco-Tatar people to distinguish them from the present-day Slavonized Bulgarians — are centred in north-eastern Bulgaria, the former east Moesia, which in character of landscape best suited their nomadic way of life, with its cattle breeding and looting raids. They settled in yurts, the typical dwellings of Eastern herdsmen used widely in Central Asia. They were circular in ground plan, three to four metres (about four yards) in diameter, with the fireplace roughly in the centre. Apart from traces in the ground the appearance of such an ancient Bulgar yurt can be found in a marble model unearthed at Devnya. It depicts the entrance and the roof and a hunting scene is carved on the outer wall, similar to those on stone walls at Pliska or Preslav.

The presence of the original Bulgars is proved by aouls, fortified settlements or rather military camps, some of which later developed into towns, e.g. Pliska or Preslav. One of these aouls was investigated near the village of Tsar Krum in the vicinity of Shumen; it was probably identical with the aoul of Khan Omortag, who cruelly persecuted the first Bulgarian Christians in the first half of the ninth century. It has a gateway with dwellings for the guards, stairs, spacious buildings, which could have been barracks and brick-paved open spaces which must have served as assembly places. The military purpose is further confirmed by finds of weapons and horseshoes.

61

![]()

The burial grounds of the original Bulgars differed greatly until they began to mix with the Slav population. Unlike the Slavs, for whom cremation was characteristic until they adopted Christianity, they buried their dead uncremated, mostly with the head towards the north, sometimes in pits with side chambers. Fear of the dead was typical of the nomad inhabitants of the eastern steppes; they prevented their return by piling up stone mounds above the graves, or the amputation of feet and similar practices, which are known also from ethnographic studies in connection with the belief in vampires.

The first great burial ground of this type was excavated near Novi Pazar close to Pliska, on the banks of the Kriva river. Men, women and children were accompanied by roughly the same offerings: vessels, knives, buckles, ear-rings, beads, and bone needles; in the graves of rich men there were, in addition, weapons, arrows, bone-inlaid quivers, sabres, spears and axes. Some tombs held amulets in the form of eagles' claws, hare or dog bones, connected with the animistic and totemistic beliefs of the Turkic steppe tribes. The bones of other animals prove that the dead were even given food for their journey to the other world. In a number of cases the Bulgars buried the dead with their horses. On many skeletons one can observe artificial deformation of the skulls, which is typical likewise of the practices of the Eastern nomads. Later, under the influence of the Slavs, the Bulgars began to cremate their dead.

The typical outfit of an Avar warrior included a nomad's bow with triple-bladed arrows, a sable, a single-bladed sword, an axe, and the horsemen had stirrups and reins (Holiare, Slovakia).

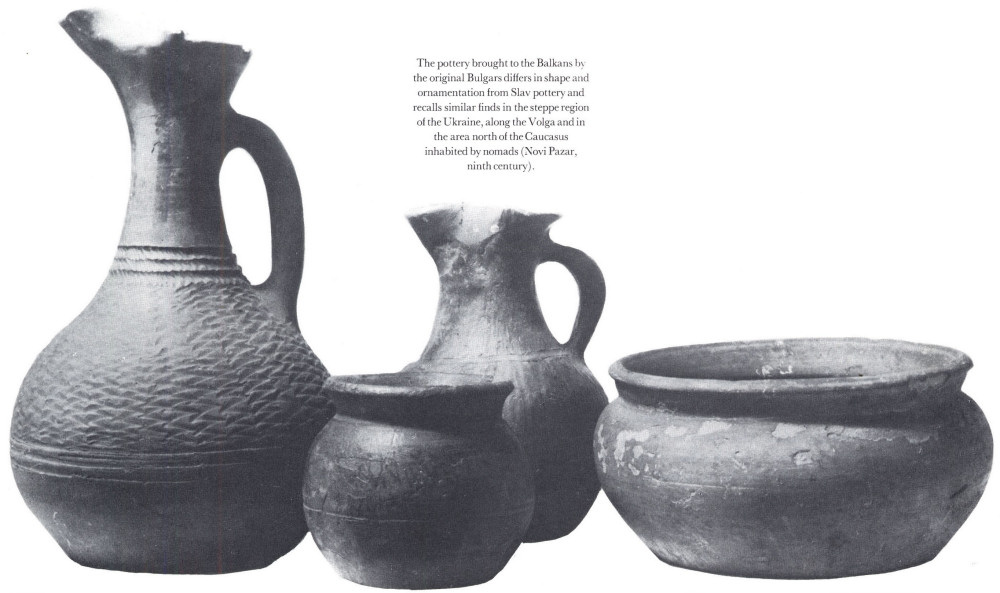

The Bulgars brought pottery along from the East, which differs greatly from the Slavonic type both in its dark-grey or dark-brown colour and in its shape and ornament. There are, for instance, round pots with polished linear or trellis patterns and similarly decorated jars (oinochoé), jugs, little amphorae, casks and dishes. Similar items have been found in the entire steppe regions of the Ukraine as far as the Volga and to the northern slopes of the Caucasus, where the Bulgar nomads lived or where they came into contact with the local tribes of the Sarmatians, Alans and Khazars. Soviet archeologists call them the SALTOVO-MAYATSKAYA CULTURE. Some shapes resemble antique patterns, but not in their contemporary Byzantine form but in older types, which survived among the steppe tribes who had long ago been influenced by the Greek colonies along the Black Sea. The Byzantine influence showed more in the towns, e.g. in the greenish glaze of pottery from Pliska and Preslav. Very soon the Bulgars began to use also Slav pottery, just as the Slavs adopted Bulgar receptacles, and gradually the merger of the two ethnic groups becomes reflected in the change and merger of different types of these common household utensils.

The Slav population of the ninth to eleventh centuries lived in similar settlements and equally simple huts dug into the ground as in the preceding period. Apart from that, however, they also built hill-forts fortified with earthworks, moats and even stone walls. In these hill-forts semi-subterranean dwellings have

62

![]()

been found as well as houses on the ground, sometimes with stone foundations. The development of craft industries is reflected in finds of wrought metal, glass and pottery workshops with kilns and the respective products. The finds are mainly of pottery, which followed up the preceding early Slavonic period, but is far more perfect in treatment and made of fine, well-washed sand mixed with clay, turned on a potter's wheel and decorated with incised wavy lines and linear strips.

Ear-rings of a great variety of types were found in the graves of women in the Slavo-Avar area. Such rings were often even plaited into the hair. They reflect the influence of Byzantine goldsmiths (Holiare, Želovce, Radvaň, all in Slovakia).

In the later Slavo-Avar period belt ornaments were cast, as shown e.g. by the belt end from Štúrovo decorated with a design of branches (Slovakia).

By contrast to the Bulgars the Slavs burnt their dead until they adopted Christianity and placed the ashes in pits or urns; these were sometimes covered by stones or other vessels, even placed in structures made of river boulders or accidentally found Roman bricks. They added gifts to the urns in the form of knives, arrows, stirrups, agricultural tools, jewels, whorls, and also some specific features such as a goldsmith's hammer.

After adopting Christianity in 865 the Slav population began to bury uncremated bodies in graves banked with stone, boulders or flagstone. Most of the offerings are now found in women's graves, where they included parts of garments, or body decorations. Many of these jewels are very similar to decorations of the ninth to tenth century found in Central Europe.

While one can observe the gradual development from cremation to inhumation burials in northern Bulgaria, in the southern parts of the country the latter rite must have existed all the time. The different manner of burial rites and types of ornaments reveal tribal differences. The culture of the southern tribes, primarily the Smolyane, shows the strong influence of Byzantium. This is further upheld by numerous finds of coins, which date the burial grounds into the ninth to eleventh centuries.

The map of archeological sites of Slavonic and Proto- Bulgar cultures has given an interesting picture of the conditions in settlement in the eighth to eleventh centuries. The settlement and burial grounds of the original Bulgars appear only in the north-eastern parts of the country, i.e. from Varna to the confluence of the Iskar and Danube, from where they extend northward as far as to Romania. Slav finds merge with these, but also appear in other parts of the country, where the Turco-Tatar Bulgars did not settle.

It is clear that such ethnic symbiosis could not take place without being reflected in the cultural sphere. And indeed Bulgarian archeologists are discovering more and more sites — especially in the centre of Bulgaria — which confirm the cultural merger of the two ethnic groups, both in types of dwellings, pottery, ornaments and in burial rites. In a number of settlements Slav semi-subterranean dwellings stood next to Bulgar yurts as an expression of the peaceful co-existence of the population. As the Bulgars went over to the settled life they adopted the Slav type of dwelling, and in certain cases even adopted the cremation rites of burial. The Slavs used Bulgar pottery in their households and in the nomad yurts and in military camps we can, on the other hand, find pottery of a Slav type. A good example of this co-existence is common burial grounds, e.g. in the vicinity of the little town of Devnya, west of Varna. Further to the west the Proto-Bulgar elements disappear. In north-western Bulgaria the Slavs used only their own pottery, in the south of the

63

![]()

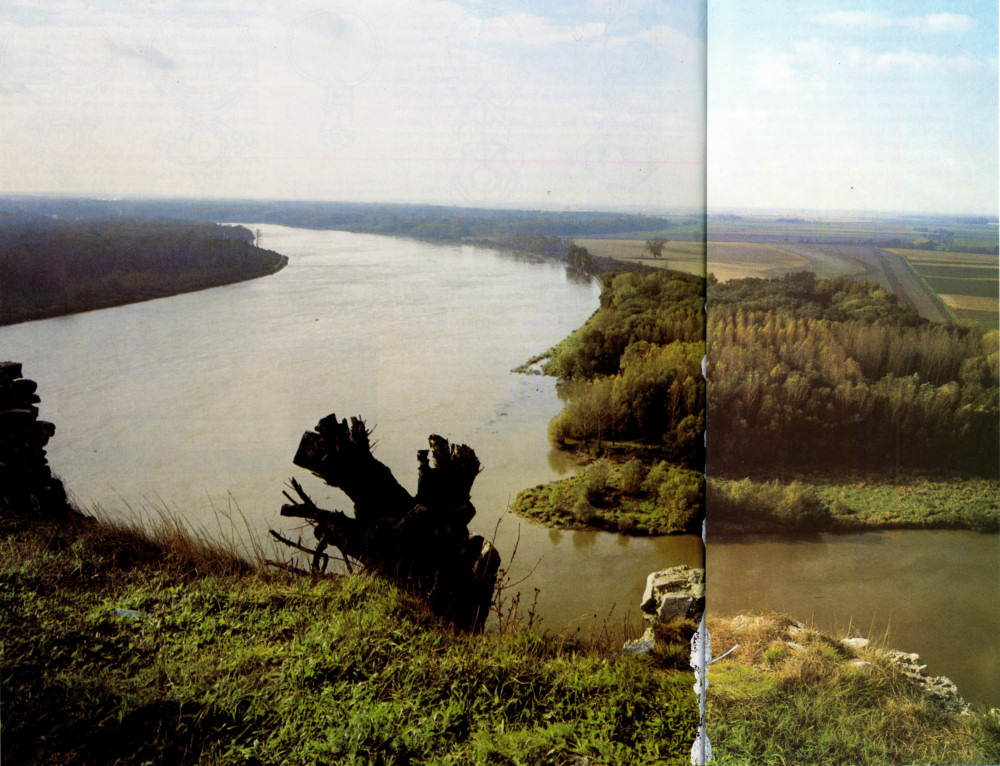

The Danube once formed the border between the world of antiquity and the barbarians, and it served as one of the main routes across Europe, attracting Germanic and Slav tribes and the eastern nomads. One of the key points was the confluence with the river Morava, which was guarded by the rocky cliffs of Devin.

Balkan mountains we do not find any Proto-Bulgar artefacts at all.

This process, which took place relatively quickly in the ninth century, led to the Slavonic Bulgarians. What is surprising is the archeologists' discovery that the original Bulgars did not represent a numerically small group, as used to be assumed. Their rapid Slavonization was aided not only by the numerical superiority of the Slavs but also by their economic superiority, for in the framework of the Bulgar state the Proto-Bulgars represented only the military element, while the Slavs formed the economic and administrative component. Of equal importance was their cultural predominance, confirmed by the adoption of the Slavonic form of Christianity and the Slavonic literary tongue. Thus it came about that the terms Bulgar and Slav were identical already in the first half of the tenth century.

The role played in the life of the South-European Slavs by the Turco-Tatar Bulgars and in the development of the Central European Slavs by the Avars was performed in the history of the Eastern Slavs by the Khazars of the seventh to tenth centuries. They were likewise a nomad people of Turkish origin, related to the Bulgars, whose original homes were in Central Asian Daghestan. From there they followed the ancient steppe routes of the nomads at the time of the Hun and Avar migrations to the west. They were first mentioned in the year 627, when they were fighting as allies of Byzantium against the Persian empire of the Sassanids. In the same century they began to rule the Caucasian region, from where their realm gradually spread northwards to the Volga where they founded a new centre at Ityl, close to the delta of the Volga. But they only spent the winter there, for as true nomads they were constantly on the move and preferred life in the steppes. Archeologists have found traces of them in the form of finds of the Saltovo-Mayatskaya culture mentioned in connection with the Bulgars. A peculiarity of their spiritual life was that, under the influence of Jewish traders who came to Ityl, they adopted the Jewish faith. They helped the Slav tribes in the Ukraine to shake off the Avar yoke, but they then occupied the former eastern parts of the Avar Empire; at one time their realm spread from the lower reaches of the Danube to the Volga and further east, from Kiev in the north as far as the Crimea to the south, where they became neighbours of the Byzantines. Their expansion was partly the cause of the migration of the related Bulgars and of the arrival of the Bulgars on the territory of Bulgaria today. The Khazars left a strong influence on the Slavs in the region along the middle reaches of the Dnieper, where later the core of the Kievan state was formed. Its establishment, together with the invasion by other Eastern nomads — the Pechenegs — led to the decline of the political power of the Khazars after the end of the ninth century. The last blow was struck by Prince Svyatoslav of Kiev when he conquered their centre at Ityl between 965 and 969.

64-65

![]()

2. THE PRESSURE OF THE GREAT POWERS AND THE FIRST ORGANIZED STATES

The Slavs who settled in Central, South-Eastern and Eastern Europe in the sixth and seventh centuries, did not come into contact only with the nomads, some of whom moved about in their midst. They became involved equally in the struggle between the great powers of the time. To the east there was Byzantium, which grew up on the ruins of the eastern parts of the Roman Empire and brought its influence to bear mainly on the Balkan and Eastern Slavs (and only for a time on those in Central Europe). In the west lay the newly rising Frankish Empire, which laid claims to the heritage of the Roman Empire. The Franks put up a barrier to Slav expansion into Central Europe and the northwestern parts of the Balkan peninsula; it was there that the two great powers met face to face, and both were to prove of fundamental importance in the further political and cultural development of the Slavs.

Pottery was made in the Slavo-Avar area mainly by Slav potters, who also used the ancient traditions handed on by the remnants of the Romanized inhabitants of the vanished Roman provinces (finds from the burial ground at Devinska Nová Ves, Slovakia).

The rise of Frankish power is linked with Clovis (Chlodovech), who adopted Christianity in the year 496. He broke the power of the Visigoths and ruled the former Roman province of Gaul. The Germanic Franks soon merged with the local inhabitants, thus forming the basis of what later became the French nation. The successors to Clovis, members of the Merovingian dynasty, gradually came to rule over further Germanic

66

![]()

tribes, the Burgundians, Angles, Saxons, Thuringians and Bayuvari and thereby shifted the frontiers of their realm in the direction of the Slavs, who were, at that time, penetrating to the Elbe, the Main and the Danube. In the Danube region the Slavs encountered the Avars, who had occupied the Carpathian Basin and whose power extended as far as the river Ems in Austria.

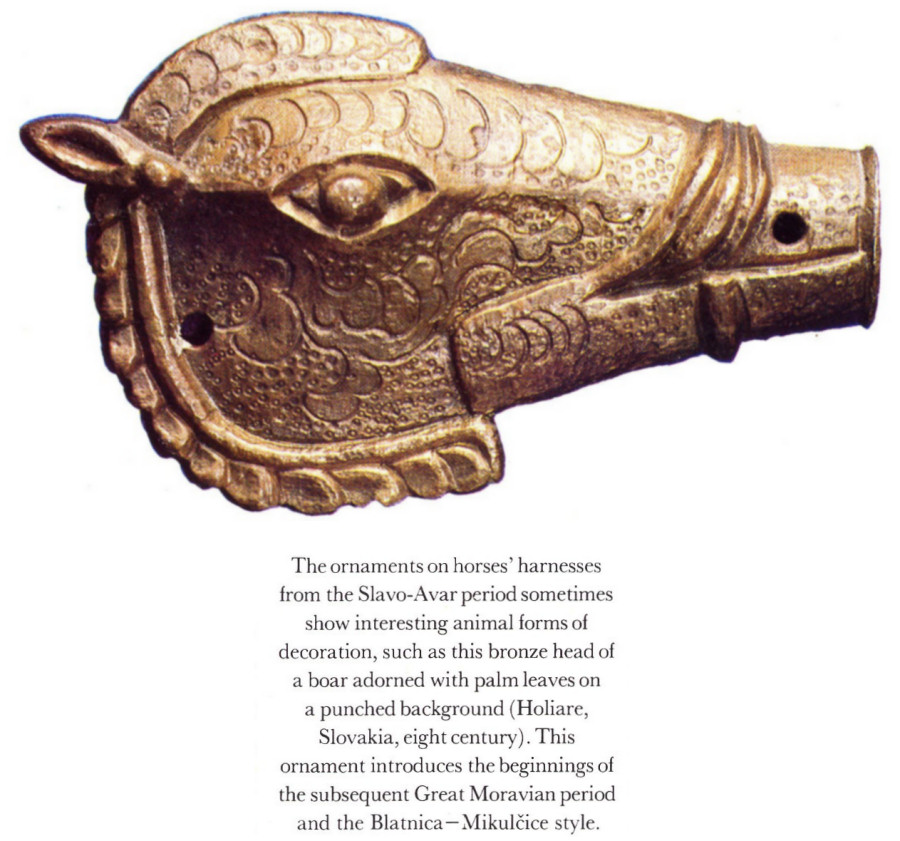

The ornaments on horses' harnesses from the Slavo-Avar period sometimes show interesting animal forms of decoration, such as this bronze head of a boar adorned with palm leaves on a punched background (Holiare, Slovakia, eight century). This ornament introduces the beginnings of the subsequent Great Moravian period and the Blatnica—Mikulčice style.

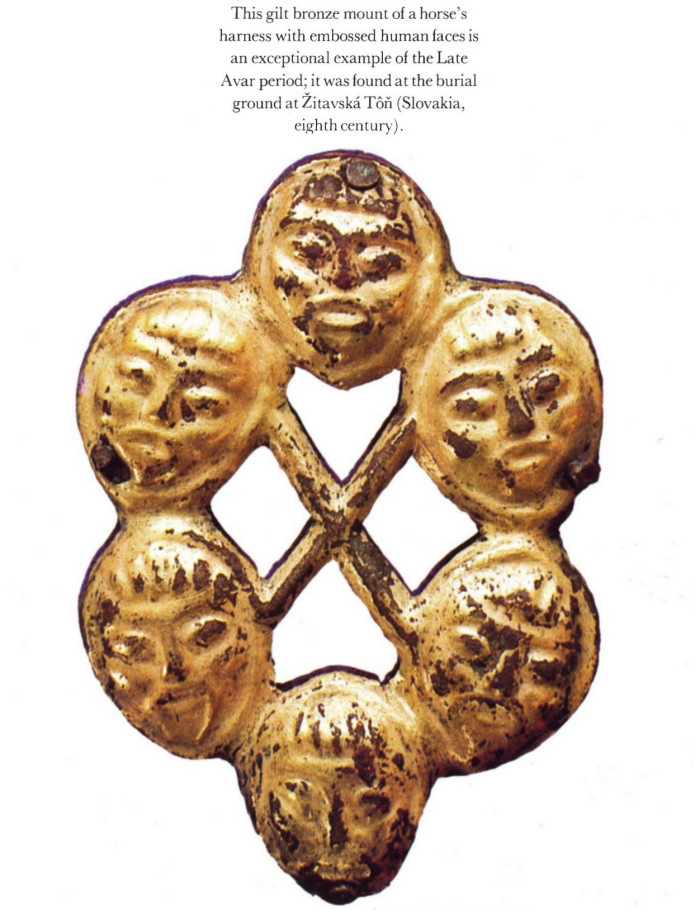

This gilt bronze mount of a horse's harness with embossed human faces is an exceptional example of the Late Avar period; it was found at the burial ground at Žitavská Tôň (Slovakia, eighth century).

In this way the Slav settlers in Central Europe found themselves caught between two fires in the second half of the sixth century. But this situation also had positive aspects, as it stirred them in their weak tribal dispersion and provided an impetus for political unification, and the establishment of the first Slav state, the Empire of Samo.

The first centuries of Slav settlement in Central Europe are veiled in historic darkness and can only be explained on the basis of archeological evidence. But one written record has survived which sheds some light on their fate in the seventh century — the Chronicle of Fredegar, an anonymous writer traditionally known by that name. It came into being in Burgundy some time between 640 and 660 as part of a work that was partly compilation, partly original — especially where it talks about Merovingian France at the end of the sixth and in the first half of the seventh century.

67

![]()

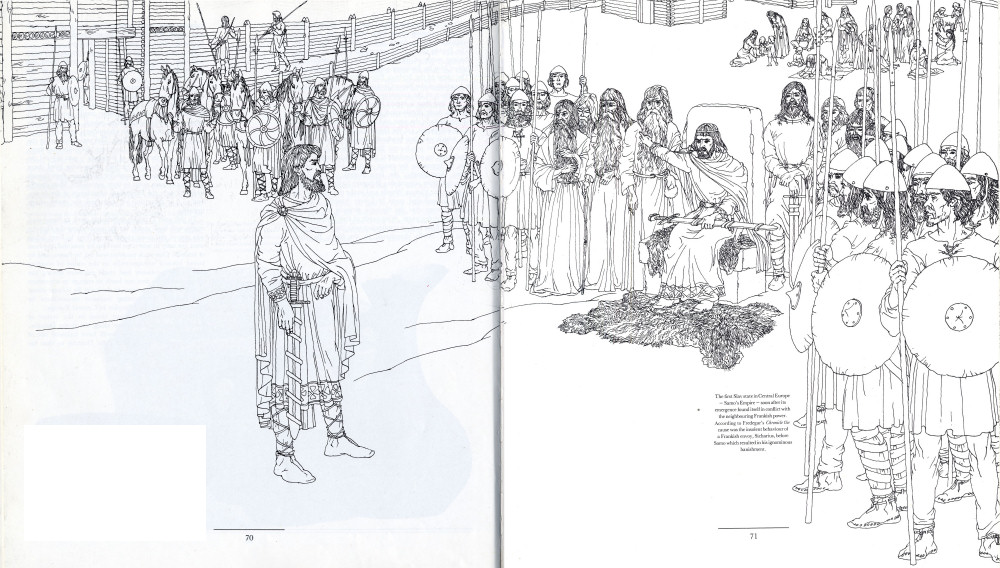

That is the part that interests us most, for it reveals valuable information about the Slavs, probably learnt from Frankish merchants, who visited the lands of the Slavs in search of trade. One of these merchants was Samo:

"In the fortieth year of the rule of Chlothar (i.e. 623—624) a man named Samo, by birth a Frank de pago Senonago (today's area of Sens in France) joined a larger group of merchants and set out to the land of the Slavs, called Venedi, to do trade there."

In those restless times such a journey required not only business skill but military fitness. Samo travelled at the head of an armed band and reached the Slavs at the very moment when they were rising against the unbearable domination of the Avars. The chronicler describes their undignified serfdom in gloomy words: the Avars demanded tithes, raped their women, and forced them to fight in the front ranks. The uprising was led, he said, mainly by their own sons born of Slavic women. Samo immediately took their side and acted so bravely that the grateful Slavs, after their liberation, chose him as their ruler. He then married twelve Slav women, had twenty-two sons and fifteen daughters and ruled happily for thirty-five years. All Other battles that the Slavs Waged against the Avars finished in victory for the Slavs. Moreover, the Avars were defeated outside Constantinople in 626, which was a contributory factor in the development of the new state of the Slavs.

The Turco-Tatar Bulgars lived in yurts as was the custom of the Eastern nomads. Their appearance is shown on a stone model found at Devnya near Varna with an incised hunting scene.

But these new conditions irritated their western neighbours, the Franks, whose expansion likewise aimed in that direction. The Frankish King Dagobert (629—638/9) therefore used a local incident, the disgraceful expulsion of his arrogant messenger Sicharius from Samo's court, as an excuse and set off with a large army against Samo. After minor success he suffered a humiliating defeat at the fort at Wogastisburc. The victorious Slavs then attacked the Thuringians by way of revenge and laid waste other parts of the Frankish kingdom. Samo's success made even the Sorbian Prince Derwan acknowledge him as his ruler, having until that time been dependent on the Franks.

The above account is from Fredegar. His story is an attractive one; his knowledge of the conditions in distant lands is certainly remarkable, but they only partly satisfy the inquisitive scholar. For, like all old chroniclers, Fredegar is very sparing in words regarding exact geographical data: he had no idea what difficulties he was preparing for historians, who for two hundred years have vainly been trying to agree where the centre of Samo's rule actually was and where Wogastisburc and its remarkable fort were located.

68

![]()

These can be determined only very roughly. The Slavs in question must have been, on the one side, neighbours of the Avars, on the other, of the Franks. The Franks called their immediate neighbours by the ancient name of the Venedi, used by Fredegar, and before him by Jordanes and other writers in antiquity. The name of the Sorbian Prince Derwan also suggests a location of the Slavo-Germanic borderland — for he was prince of the ancestors of the Lusatian Sorbs.

The pottery brought to the Balkans by the original Bulgars differs in shape and ornamentation from Slav pottery and recalls similar finds in the steppe region of the Ukraine, along the Volga and in the area north of the Caucasus inhabited by nomads (Novi Pazar, ninth century).

The fact that a mixed Slavo-Avar population rose against Avar domination points, furthermore, to the borderlands to the west and north-west of the centre of Avar settlement, i.e. the Danube region in Lower Austria, which was then predominantly Slav, and southern Moravia and south-west Slovakia. This conclusion is confirmed by archeological finds, which make it possible to determine the range of Avar and Slav settlement. Accordingly, the area settled by the Avars stretched from present-day Hungary further to the west as far as the Vienna Woods and to the river Dyje in the north; it included parts of Lower Austria. Finds of pottery prove that the Slavonic element left a strong mark on these parts. Westwards of this line, as far as the river Ems and its confluence with the Danube, the area was chiefly dominated by the Slavs. Bavarian colonists penetrated among them, but in the seventh and eighth centuries their compact settlement did not go further than the west bank of the Ems.

We can conclude from the geography of settlement and from archeology that the Slavs, who under the leadership of Samo rose against the Avars in the seventh century, must have lived, in great likelihood, along the north-western borders of their empire, i.e. in Lower Austria, southern Moravia and possibly in south-western Slovakia. These were the regions where the Avar horsemen could most easily penetrate and apply their political influence, which, according to the evidence of the Frankish chroniclers, reached at one time as far as the river Ems. The region further to the north — mountainous northern Slovakia, northern Moravia and the whole of Bohemia — was beyond the reach of the Avars. The Slav tribes who lived there were free and had no reason for resistance, even though they might have come to their assistance. Most closely involved were the immediate neighbours of the Avars, and so it is there that we must seek the centre of the uprising.

To this area Frankish merchants, such as Samo was, might well have come, for the route along the Danube was one of the main routes from West to East, being used not only in war time but also by peaceful caravans of traders. One such caravan was led by Samo, and he found himself unexpectedly in the midst of warring camps. He probably had trade partners among the Slavs, and as he was not loath to engage in adventure he rallied his companions to their aid. So it came about that instead of executing business transactions he founded the first Slav Empire in Central Europe.

Wogastisburc must have stood in the centre of Samo's Empire, somewhere along the rivers Danube, Dyje or Morava. Dagobert will have followed one of the frequented routes along the Danube so that his

69

![]()

allies — the Lombards and Alamanni living to the south — could send him additional support without greater difficulties. The exact location of Wogastisburc is still unknown. We only know one hill-fort in the assumed centre of Samo's Empire — Mikulčice in southern Moravia, whose foundation goes back to the seventh century. It cannot be a coincidence that 200 years later one of the main centres of the Great Moravian Empire grew up there. But we have no proof that either this or any of the other Slav hill-forts, especially those along the Danube in Lower Austria, was the elusive Wogastisburc.

The first Slav state in Central Europe — Samo's Empire — soon after its emergence found itself in conflict with the neighbouring Frankish power. According to Fredegar's Chronicle the cause was the insolent behaviour of a Frankish envoy, Sicharius, before Samo which resulted in his ignominious banishment.

Archeological research can only

70

![]()

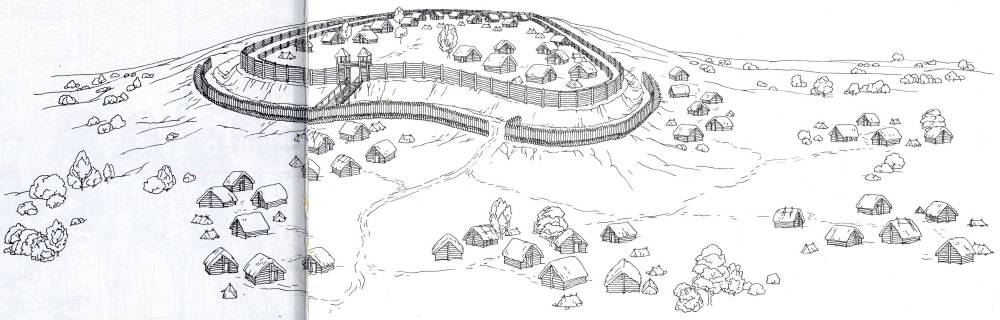

give us an idea of how Wogastisburc would have been fortified: it was probably no more than a simple palisade with a moat, or possibly a single wooden wall with earthworks. Something of this kind was found, for instance, on one of the oldest Slav hill-forts in Bohemia, Klučov near Český Brod. At the time of Samo the Slavs were just beginning, so archeological excavations tell us, to build hill-forts as permanent settlements. But the technique of fortification must have been known to them since the time before the great expansion. This is shown by the common term for "fortification" to be found in all Slavonic languages — hrad, grad, gród, gorod,

71

![]()

gard, etc. At the time of the great tribal migrations there was neither time nor reason for such expensive constructions. Hence no hill-forts are known from the early Slavonic period of the Prague type. They originated only after a certain period of settled life, when the new villages were threatened by dangerous raiders, such as the Avars, the expansion of the mighty Frankish Empire or related neighbouring tribes. The hill-forts served as refuges, but there were also permanent inhabitants who guarded such important sites. In the course of time, they became the ruling class. But this was a lengthy social process, which reached its climax in the ninth to tenth century, even if the initial impulse occurred at the time of Samo. The building of fortified centres reflects the beginning of social organization of the-Slav tribes as related in Fredegar's Chronicle and confirmed by archeological research.

The Slavs, united under the rule of Samo, could, for a time, keep their independence and resist external pressure. Since the Avar danger did not cease to be acute even after the death of Samo (658), they were soon forced, however, to chose the lesser of two evils and accept support either from the Frankish or the Byzantine Empires, which faced each other across Slav territory. In view of the serious Avar threat both these powers became allies. Under the Frankish King Dagobert (629—638) and the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610—641) this friendship was confirmed in a treaty. It was the very time when the Slavs were rising against the Avars. The Byzantines, furthermore, supported the Serbs and the Croats, who drove the Avars out of the north-western parts of the Balkan peninsula, liberating Dalmatia, Illyria, the territory between the Sava and Drava, and Carinthia settled by Slavs. It was a large section of the sphere of interest of the Byzantines, into which the Franks were beginning to penetrate.

This penetration proceeded under the new dynasty of the Carolingians, founded by Pépin in the year 752. His successor, Charlemagne (771—814), dealt a mortal blow to the Avars, who at that point completely vanished from history. He ruled over the Slavs living on the territory of ancient Noricum and Pannonia, i.e. in Styria, Carinthia and the land between the Sava and the Danube. He even reached the Istrian peninsula on the Adriatic and founded what became known as the Friulian Mark. This was to be the springboard for Frankish expansion into the Balkans. After heavy battles the Franks occupied Croatian Dalmatia, whose coastal towns had until that time been the domain of Byzantium. The regions inhabited by Slavs along the coast of the Adriatic Sea thus became the point where the two great European powers of the time met head on in the eighth and ninth centuries.

A relief of a horseman found on a stone at Hornhausen near Halle, which gives an idea of a Germanic warrior from the time around 700. It probably comes from a tomb, though some regard it as depiction of the god Wotan.

Further penetration of the Franks into the Balkans was put a stop to by the uprising of the Pannonian Croats under Ljudevit (819—833), who was the first to try, though unsuccessfully, to unify the Slav tribes on

72

![]()

the territory of Yugoslavia. Another factor was the newly rising empire of the Bulgars, whose power under Khan Krum (803—814) spread into Serbia and along the Tisza in Hungary, once the Avars were defeated. Krum's successor, Omortag (814—831), invaded Pannonian Croatia and ruled over it for a time. Though later only Slavonia and the territory around Sirmium remained under the Bulgars, their expansion put an end to the ambitions of the Franks in this part of Europe.

Though it is not known where Wogastisburc lay, near to which Samo defeated the army of the Frankish King Dagobert, we can get an idea of its fortifications from excavations carried out on one of the oldest Slav hill-forts in central Bohemia, at Klučov.

Charlemagne put forward the idea of a new universal empire, which was to be an heir to the Roman Empire, at least its western parts, now under Christian influence. The realization of this idea was naturally linked with armed expansion aimed against the independent Germanic tribes such as the Saxons, and against the Slavs, who, at that time, were spreading further west from the Elbe, the Saale and the Bohemian Forest. This advance was stopped by the establishment of Marks. The Ostmark was aimed mainly against the Moravian and Bohemian Slavs — and later developed into the dukedom of Austria. The Thuringian Mark (Limes Sorabicus) was aimed against the Sorbian tribes; some lesser Marks on the Elbe against the Veletians (Liutizi) and the Saxon Mark (Limes Saxonicus) against the Obodrites. The borders of these Marks ran along the river Elbe. The Slavs on its left bank became, in fact, Frankish subjects, while the tribes on the right bank retained their independence for many years. But they were under constant pressure which intensified after the tenth century.

Bohemia became a major centre of Frankish interest; it had long been on the fringe of development, hidden behind its girdle of border mountains and sunk deep in the mythical period of its history. The road to Bohemia opened up before the Franks, once they gained control over the Slav tribes along the upper Main, Rednitz and Pegnitz rivers in north-eastern Bavaria. The first onslaught came via the Cheb region and along the valley of the Ohře. In 805 the Frankish army reached the mighty hill-fort at Canburg above the Kokořín valley but had to retreat without achieving its aim. Later mutual relations improved, since in 822 representatives of the Czechs and Moravians appeared at the Imperial Assembly of Louis the Pious at Frankfurt. In 845 there is a record of the baptism of fourteen Bohemian princes at Regensburg. This report shows how scattered the Czechs were in their tribal princedoms, which still had a long way to go towards some degree of state organization. Frankish Christianity, with mainly political aims in mind, had not sunk roots in Bohemia when, several decades later, the first historical ruler of the country, Bořivoj, had to be baptised anew.

In the meantime, Moravia under Prince Mojmír

73

![]()

grew in political importance. The local tribes unified before those in Bohemia, and Mojmír, furthermore, had managed to add the Slovakian Nitra area to his realm, from where he expelled Prince Pribina.

Samo's Empire emerged after a major uprising against the Avars in the twenties of the seventh century along the north-western borders of the Avar lands. In view of lack of information we can get no more than an approximate idea of its size.

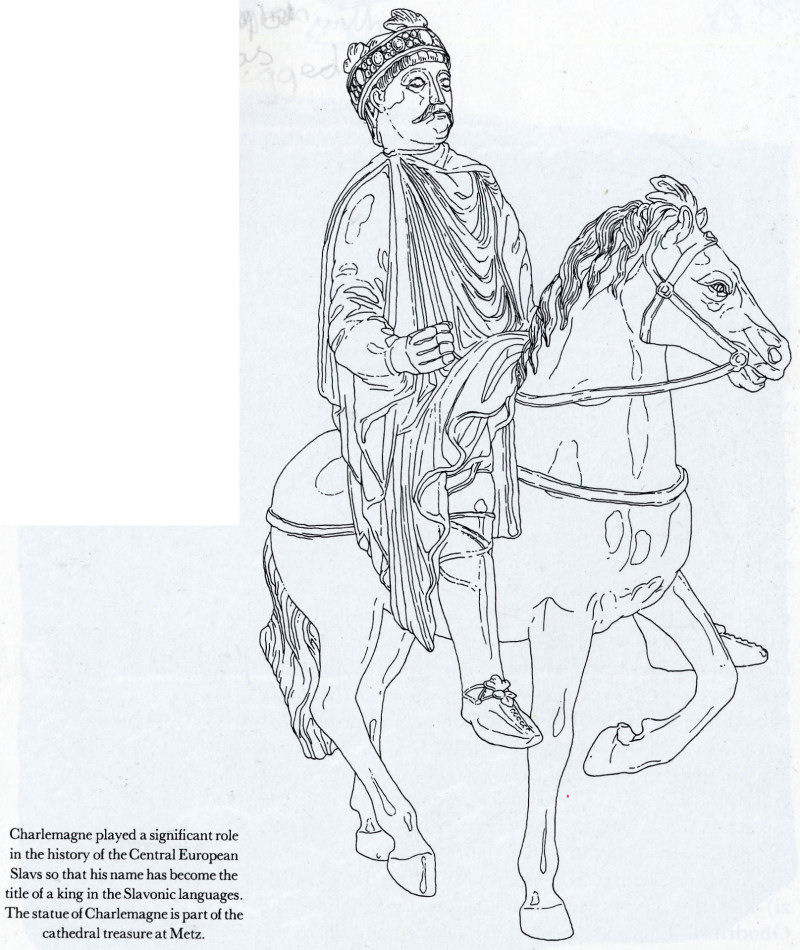

Charlemagne played a significant role in the history of the Central European Slavs so that his name has become the title of a king in the Slavonic languages. The statue of Charlemagne is part of the cathedral treasure at Metz.

The Frankish Empire did not interfere in Moravian affairs until Louis the German, who aided Mojmir's nephew Rastislav to become ruler. But on his return home he was defeated by the Bohemians who then attacked the Frankish territory themselves. A new Frankish expedition in 849 ended in catastrophe. This enabled the Czechs and Moravians to gain greater independence. Another expedition in the years 856/7 was only of limited importance, altering merely local conditions. The Franks drove from a castle belonging to Wiztrach his son Slavitah and put in his place the brother, who obviously had made an alliance with them. Attacks continued from both sides. During one of these the

74

![]()

Franks got hold of the rich dowry of an unknown Bohemian bride, whose wedding procession was going to Moravia. It may have been the bride of Svatopluk, the successor to Rastislav, who fought constant battles with the Franks. In the year 872 Carloman undertook a large but unsuccessful expedition against him. Success was reached only by troops under the leadership of Archbishop Luitbert, who came to Bohemia and defeated five Bohemian princes: Světislav, Vitislav, Heřman, Spytimír and Mojslav. It is not known where these princes were rulers, but the smaller number of names indicates that, at that time, the process of unification of the Bohemian tribes had advanced, probably under the pressure from the Franks. Then the first historical prince, Bořivoj, appeared on the scene. Some time in 869—870 he adopted Christianity in Moravia where the Byzantine missionaries Constantine and Methodius were then working. This cultural and political orientation of the Bohemians and Moravians towards Byzantium was not of long duration. No more than one year after Svatopluk's death (895) the Czech princes once again acknowledged Frankish sovereignty at an assembly in Regensburg. The orientation towards the Latin West determined the further development of the Central European Slavs.

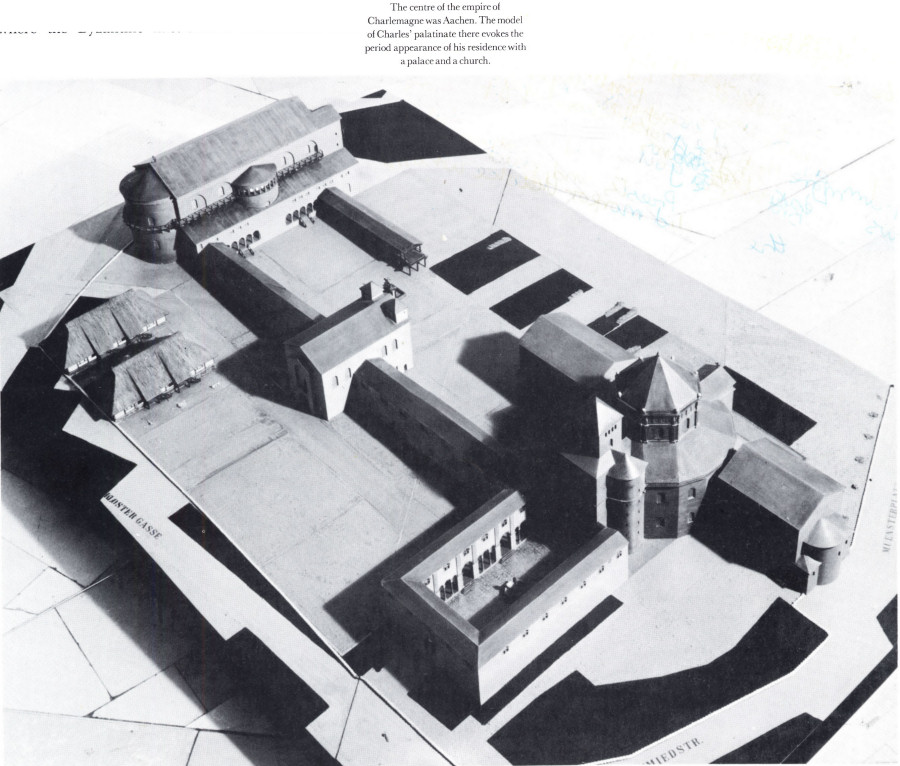

The centre of the empire of Charlemagne was Aachen. The model of Charles' palatinate there evokes the period appearance of his residence with a palace and a church.

While the Western Slav tribes were exposed to the pressure of the Frankish Empire, the Slavs on the Balkans were exposed primarily to Byzantine influences, which, for a time, reached as far as Central Europe but affected to a far greater extent the economic, political and cultural development of the Eastern Slavs. This influence formed a kind of counter- current to Slav expansion towards the south, which, for more than two centuries, threatened the core of Byzantium

75

![]()

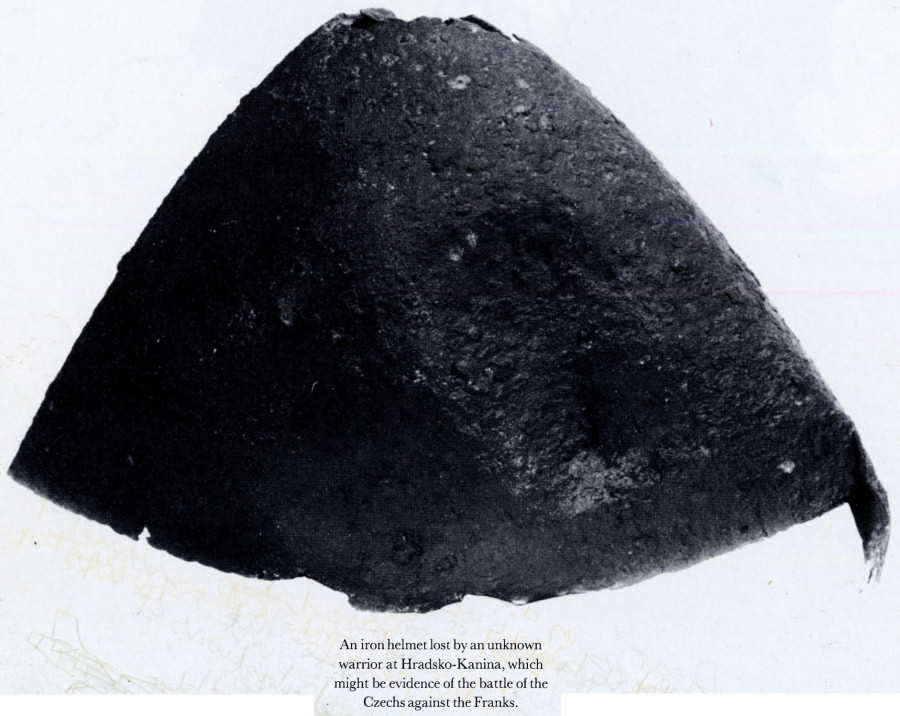

The Franks undertook their first onslaught against the Czech Slavs in 805. But they did not achieve much success although their army advanced as far as castle Canburg, which, excavations confirm, can be identified in great likelihood with the hill-fort Hradsko-Kanina near Mělník in central Bohemia.

76

![]()

by their occupation of Greece, until, in the end, the Slavs succumbed to their culturally stronger opponent. The relatively speedy assimilation of the Greek Slavs was facilitated by the fact that they were not politically organized, as had been case with Samo's Empire, the Bulgars, Serbs and Croats. They often lent their services to the Byzantine army where they adopted Greek ways and even reached leading positions. The founder of the Macedonian dynasty Basil I (867—886) may himself have been of Slav origin.

The Slavs who settled in Central and South-Eastern Europe soon found themselves drawn into the power struggle between the two great empires of the day: the Byzantine Empire to the east and that of the Franks in the west, the latter growing particularly under Charlemagne (771—814).

The relations between Byzantium and the Balkan Slavs were varied. As we have shown, the Croats were partly under Byzantine and partly under Frankish influence. Byzantine influences spread mainly from the coastal towns of Dalmatia. In the tenth century the Croats became vassals to Byzantium, but from the second half of the eleventh century Western influences again dominated, which can be found in the distinct culture of the Croats to this day. On the other hand, the Serbs acknowledged Byzantine sovereignty almost continuously

77

![]()

until the twelfth century, when they became independent but retained cultural links. The same is true of the Bulgars, who defended their political independence in numerous battles against the Byzantines until the early eleventh century. Tsar Boris I (852—889) even intended to adopt the Latin form of Christianity as a cultural counterbalance to Byzantium. In the end he availed himself of a different means of achieving this end: he gave asylum to disciples of Methodius, who had been expelled from Moravia by Svatopluk and were seeking refuge in Bulgaria, where they introduced Christianity in its new, Slavonic form. This suited the endeavours of the Bulgarian rulers in their quest for independence. This form of Christianity, however, brought them culturally closer to the Byzantines.

An iron helmet lost by an unknown warrior at Hradsko-Kanina, which might be evidence of the battle of the Czechs against the Franks.

The contacts between Byzantium and the more remote Eastern Slavs were, at first, in the form of wars or trade. Military encounters played an important part especially among the militant Scandinavian Varangians, who settled in Russia after the ninth century. Most of them were unsuccessful on the Slav side. But trade contacts, secured even in the form of treaties, developed very intensively. The famous route from the Varangians to the Greeks led along the rivers Volkhov, Dvina, Dnieper, and the Black Sea — and furs, amber, honey, wax, resin and slaves were moved down it. In the opposite direction metal objects, precious materials and spices were transported. When in 989 Prince Vladimir adopted Christianity, a new stage in profound cultural penetration began and it found its reflection in architecture, literature, and in religious and legal life.

The Byzantine influences on Slavonic culture showed most clearly in architecture — ecclesiastical and secular. This is exemplified in numerous churches all over the Balkans and in Eastern Europe, e.g. the palaces of the Bulgarian rulers at Pliska, Preslav and Madara, adorned with mosaics, marble and glazed tiles. And in craftsmanship, the work of goldsmiths and potters. Byzantine jewels and pottery enjoyed great popularity not only among the Slavs who came into direct contact with Byzantium, but all over Central Europe where they were one of the main influences in the goldsmiths' work of the Great Moravian Empire in the ninth century.

78

![]()

Contacts between Central Europe and Byzantium are confirmed by a hoard of silver jewelry, vessels, coins and sherds from the seventh century, found at Zemiansky Vrbovok in Slovakia.

79

![]()

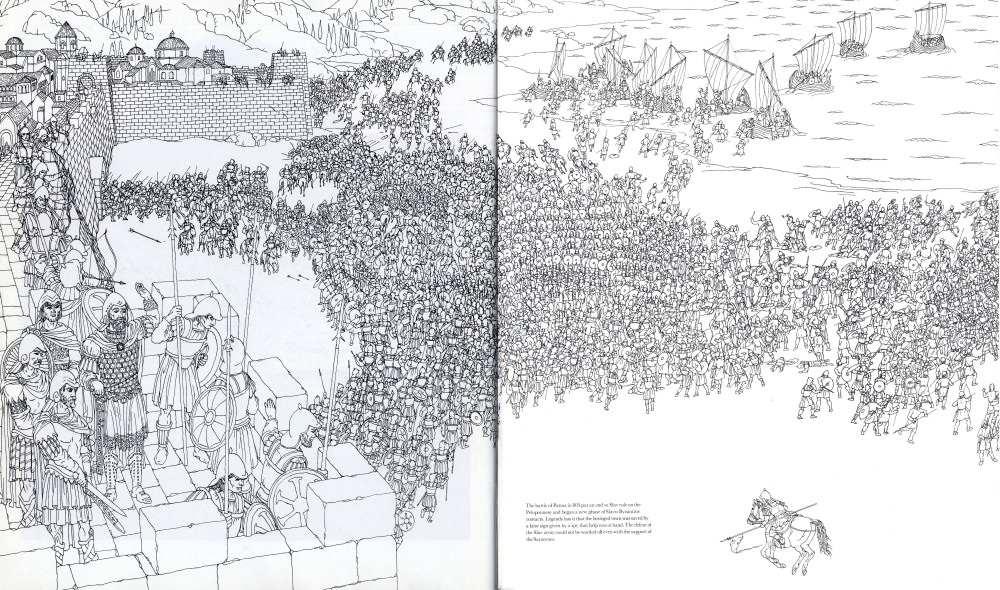

The battle of Patras in 805 put an end to Slav rule on the Peloponnese and began a new phase of Slavo-Byzantine contacts. Legends has it that the besieged town was saved by a false sign given by a spy that help was at hand. The defeat of the Slav army could not be warded off even with the support of the Saracenes.

80-81

![]()