IV. GODS, DEMONS AND SHRINES

Arkona — symbol of defiance and the doom of Slavonic paganism. The place where the famous Svantovit temple once stood has been washed away by the waves of the Baltic Sea.

1. THE RELIGIOUS IDEAS OF THE SLAVS

Slav paganism grew out of the common Indo-European core and therefore has certain features identical to those of the ancient Indians, Iranians, Greeks, Romans, Celts, Germans and Balts. This is true of certain basic terms such as div, diva, divý to indicate a spirit of nature; these correspond to the old Indian deva, the Iranian div, daeva, the Latin divus, deus, dea, the Lithuanian devas, etc. Similarly the expression for "god" bůh, or bog corresponds to the old Indian bhága (master), the Iranian baga, bag or the Armenian bagin. Certain Indo- European groups held the god of thunder in the greatest respect. In the sixth century the Byzantine writer Procopius mentioned that the Slav Perun corresponds to the Greek Zeus and Roman Jupiter, and the Germanic Thor. Apart from these similarities, or alien influences, the Slavs had beliefs of their own: there even were differences between individual groups and tribes.

On the whole, we possess far less information about the spiritual life of the pagan Slavs than about the religious ideas of other ancient Europeans. This does not mean that their life was poorer in this respect, but they entered the stage of history and the awareness of the cultured nations at a relatively late period, so that they had no Caesar or Tacitus, who might have related their history with unbiased objectivity as was the case of the Celts and the Germans. When they did appear on the scene, civilized Europe was already Christian and was not greatly interested in or showed an understanding of the spiritual life of barbarians, whom they viewed with condescension and with the sole aim of bringing them at the earliest possible date into the Christian community. Contemporary evidence is not always of equal value; apart from reliable reports by eyewitnesses there is often second- or third-hand information with various degrees of distortion. Later chroniclers, remote in time and thought from the pre- Christian period, added many facts, and even invented them when they misunderstood popular customs. The legends of the first Czech saints from the tenth and eleventh centuries and the Czech chronicler Cosmas from the early twelfth century speak of gods, idols, shrines, sacrificial altars, burial rites, magic practices, and so on, but do not cite any god by name (at most they are compared with the gods of antiquity) and the

82-83

![]()

general characteristic of paganism reveals very little that is concrete. In the Czech lands the expulsion of witches and Church prohibitions of pagan rites in the eleventh and twelfth centuries show that there must have been a hidden stratum of ancient beliefs beneath the cover of Christianity.

This is true of all the countries where the ancient beliefs were fairly soon overlaid by Christianity, i.e. Central and Southern Europe. Apart from survivals in folklore there exists today hardly anything of the original religious ideas of the Czechs, Slovaks, Poles and Yugoslavs. Some reports about the more remote Eastern Slavs have survived in local sources, mainly the Kiev Chronicle of the eleventh century, and in Oriental (that is chiefly Arab) reports. We know relatively more about the religion of the Baltic and Polabian Slavs, who have died out. Until the twelfth century it served them as an ideological weapon in the fight for independence, for Christianity introduced by Western missionaries meant only serfdom for them and the gradual loss of national identity.

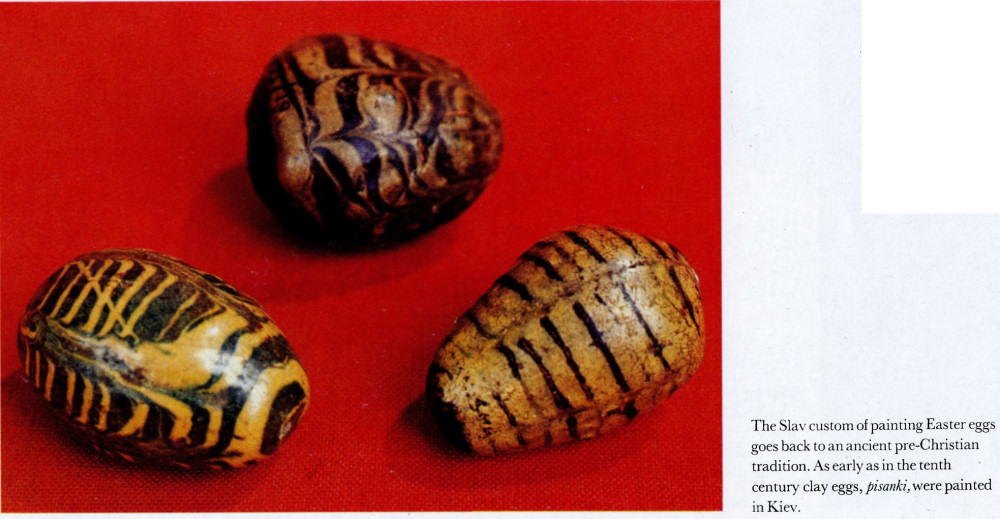

The Slav custom of painting Easter eggs goes back to an ancient pre-Christian tradition. As early as in the tenth century clay eggs, pisanki, were painted in Kiev.

In recent decades our knowledge of Slavonic religious beliefs has been enlarged by archeology, both by excavations of shrines and places of sacrifice and the finds of idols and cult objects. Objects — weapons, tools, ornaments, vessels with food and drink — were placed in the graves. The burial rites themselves developed from the original practice of cremation, when the ashes of the deceased were placed in urns, to the inhumation of uncremated bodies; this increased under the influence of Christianity. Certain objects in the graves expressed special symbolism, e.g. eggs were symbols of life (painted Eastern eggs were known among the Slavs as early as in the tenth century) and coins placed in the mouth or hands of the dead served as payment for the ferryman to the Underworld — a custom known also among the ancient Greeks and Romans. Historically and archeologically we have confirmation

84

![]()

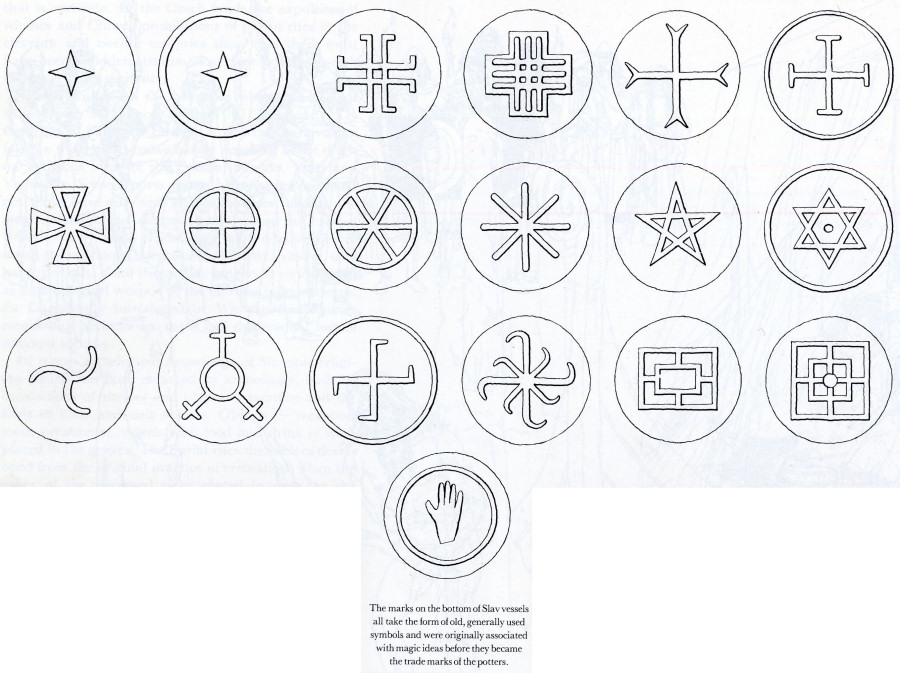

of the belief in vampires — dead persons who suck human blood and who have to be rendered powerless by the deformation of the dead body. In the same way the Slavs practised the burning of widows, a custom that survived in India until not so long ago. Even objects of daily use — weapons, tools, ornaments, pots — were marked with well-known ancient symbols such as the swastika, cross, sun-wheel, pentagram, etc., which through magic were supposed to ensure success in the relevant activity.

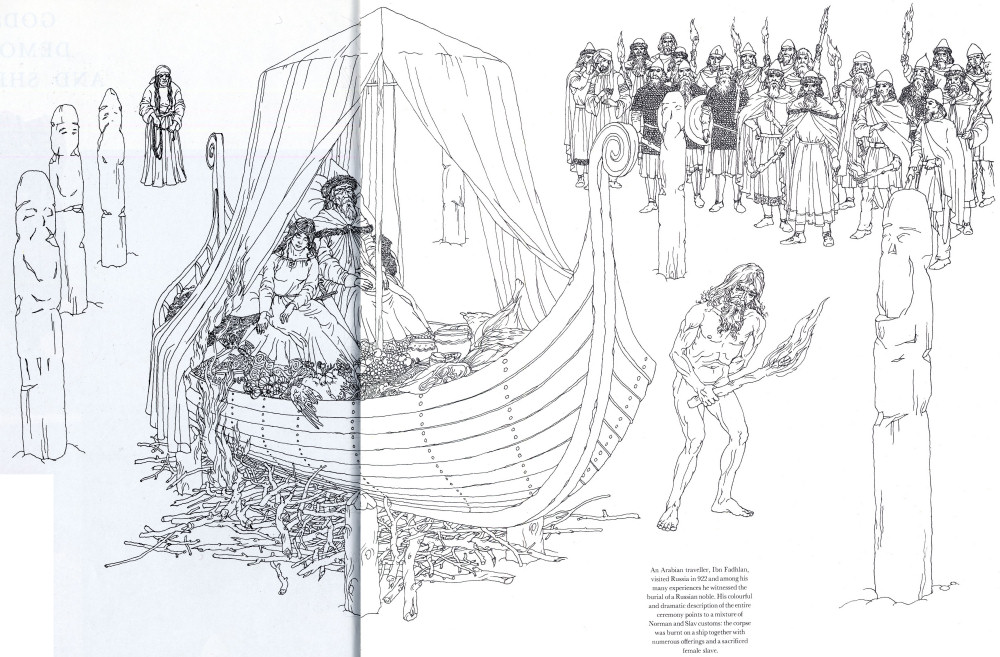

An Arabian traveller, Ibn Fadhlan, visited Russia in 922 and among his many experiences he witnessed the burial of a Russian noble. His colourful and dramatic description of the entire ceremony points to a mixture of Norman and Slav customs: the corpse was burnt on a ship together with numerous offerings and a sacrificed female slave.

85

![]()

The marks on the bottom of Slav vessels all take the form of old, generally used symbols and were originally associated with magic ideas before they became the trade marks of the potters.

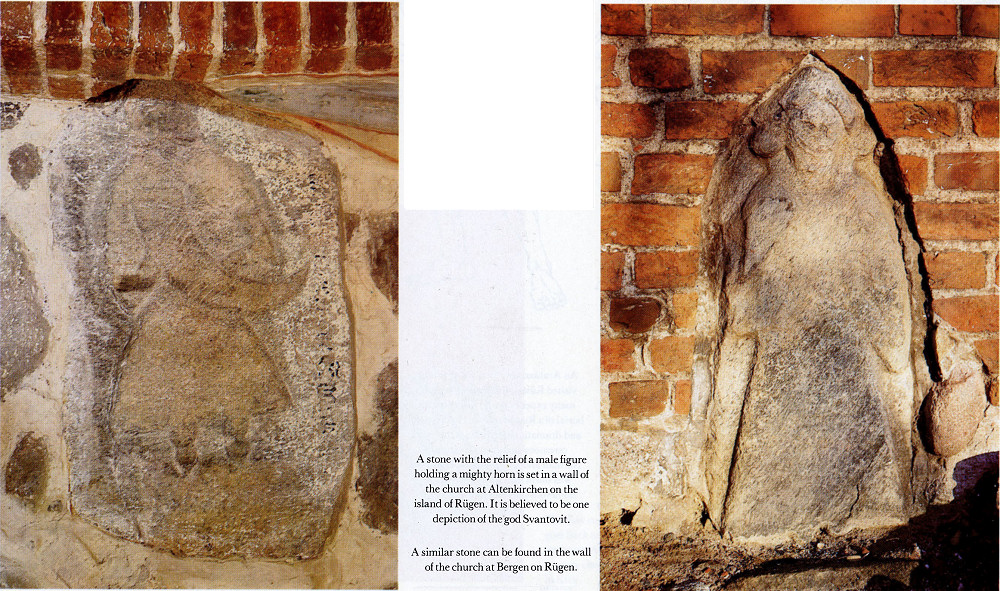

A stone with the relief of a male figure holding a mighty horn is set in a wall of the church at Altenkirchen on the island of Rügen. It is believed to be one depiction of the god Svantovit.

A similar stone can be found in the wall of the church at Bergen on Rügen.

86

![]()

Many old pagan rites live to this day in folk customs, for example carols, which relate to the festival of the winter solstice; "death" being carried outside in spring, which is a survival of the folk sacrifice to the gods of nature; the midsummer bonfire, which is all that is left of the celebration of the summer solstice.

The core of religious life was the respect for the gods and cults associated with this. Like other Indo-Europeans the Slavs, too, had their Olympus. Some gods were held in common or at least enjoyed a broader significance. This applies mainly to PERUN, the god of storms or of thunder and lightning, worshipped mainly in Russia, where in the tenth century his idols stood near Kiev and at Peryn' near Novgorod. There is proof that his cult also existed in Poland and among the Polabian Slavs, where Thursday was consecrated to him as peründan. ("Thursday" as such derives from the ancient Germanic god Thor; jeudi — dies Iovis comes from the Roman Jove). In the Czech lands Perun occurred only as a name, and in Slovakia he has survived in curses, for example, parom do teba — "May Perun strike you", and Do paroma — "By Perun".

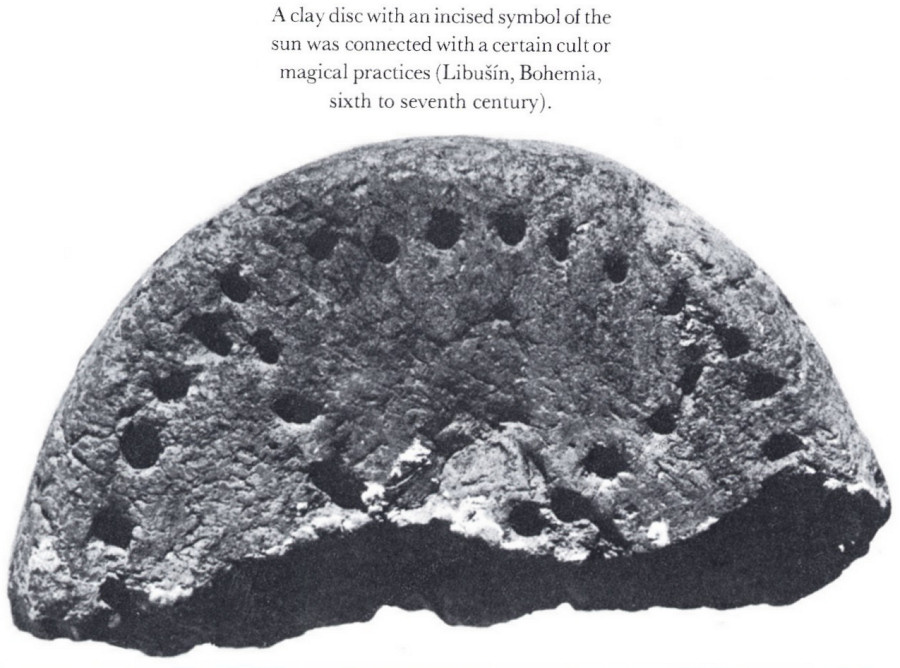

The Eastern and Western Slavs knew a SVAROG or DAZHBOG, the god of the Bright Sun, and his son SVAROZHICH was worshipped e.g. in Obodrite Rethra. Svarog's name is probably connected with the Old Indian svarga (sky), the second name Dazhbog probably meant "god-the-donor", that is, the donor of warmth and light as conditions of life. Svarozhich was the personification of fire, understood as the son on earth of the sun. In the Czech region proof of the cult of the sun was found in symbols, e.g. a cross in a circle incised on a clay disk found at Libušín.

The third god of broader significance was VELES, called Volos in the east, the protector of herds and farming. In the Czech lands traces of his cult survive only in old folk idioms, such as u velesa (meaning "the deuce") or ký veles ti to našeptal? ("What devil put you up to it?").

The majority of gods, however, were only of regional or entirely local importance. In Russia they worshipped, for example, STRIBOG, the god of the winds, the goddess MOKOSH, perhaps of Finnish origin, CHORS and SEMARGL, who came from the Orient, and TROJAN, who cannot have been anybody other than the deified Roman Emperor Trajan, introduced to the Slavs possibly by the Dacians.

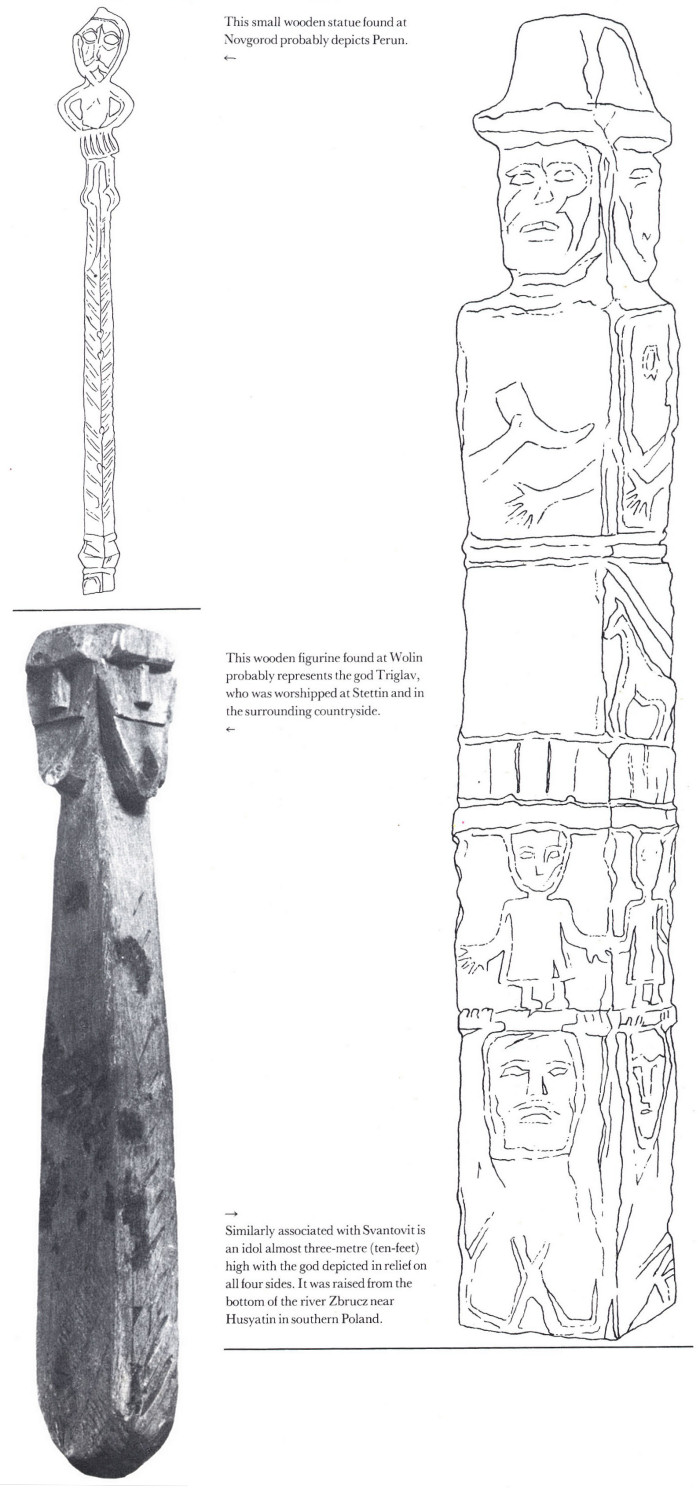

This small wooden statue found at Novgorod probably depicts Perun.

This wooden figurine found at Wolin probably represents

the god Triglav, who was worshipped at Stettin and in the surrounding

countryside.

Similarly associated with Svantovitis an idol almost three-metre (ten-feet) high with the god depicted in relief on all four sides. It was raised from the bottom of the river Zbrucz near Husyatin in southern Poland.

The Olympus of the Polabian and Baltic Slavs was particularly crowded. They clung firmly to their paganism and therefore roused the lively interest of the chroniclers of the neighbouring Christian lands. A renowned site of worship was Rethra, the centre of the Obodrite tribe of the Retharii and the famous oracle that foretold the future, especially harvests or the outcome of warfare, with the aid of the sacred horse of Svarozhich. This god was also known by the names of RADOGOST, Radigost or Radegast, which often appear as local names.

87

![]()

Another god to enjoy great fame was SVANTOVIT, whose temple stood at Arkona on the island of Rügen on the Baltic coast until the year 1168. He had four heads and held a drinking-horn filled with wine in his right hand, from the level of which he foretold the prospects for future harvests. Last century a stone idol almost three metres (about ten feet) high was discovered on the river Zbrucz in southern Poland; as it had four faces and a drinking-horn, it was immediately assumed to be a depiction of Svantovit. But that is not certain since other Slavonic gods, too, were many- headed. In Stettin (Szczecin) for instance a three-headed TRIGLAV was worshipped, at Korenica on Rügen a four-headed PORENTIUS, a five-headed POREVIT, and even RUGEVIT with seven heads. In Europe this phenomenon is relatively rare among, for example, the Celts or the Romans, but it recalls the old Indian gods, which to this day have such appearances. We cannot, therefore, eliminate some connections with the Old Indo-European culture, of which survivals can also be traced in other aspects of Slavonic paganism, e.g. in burial rites. Many-headedness must have symbolized the multiple power of the relevant god.

A pagan shrine was discovered at hill-fort Schlossberg near Feldberg, but it dates from an older period (seventh to ninth century) than legendary Rethra, with which it was once mistakenly identified.

88-89

![]()

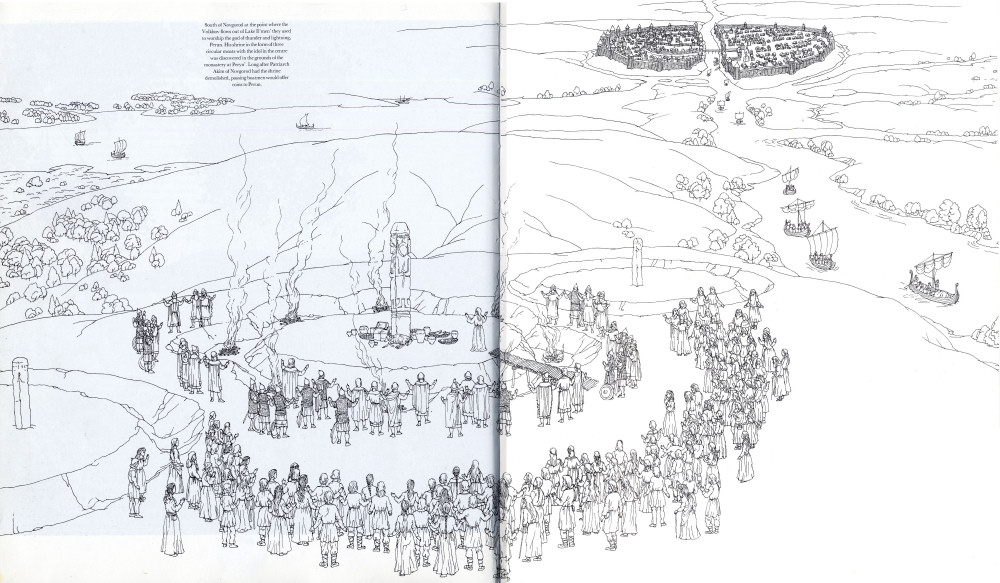

South of Novgorod at the point where the Volkhov flows out of Lake Il'men' they used to worship the god of thunder and lightning, Perun. His shrine in the form of three circular moats with the idol in the centre was discovered in the grounds of the monastery at Peryn'. Long after Patriarch Akim of Novgorod had the shrine demolished, passing boatmen would offer coins to Perun.

2. TEMPLES, IDOLS AND CULTS

A characteristic example of Slavonic religious life was the cult of Svantovit on the island of Rügen, recorded in written accounts and confirmed by excavations.

Svantovit was so famous that Western chroniclers called him deus deorum — the god of gods. Chronicler Helmold of Bosau, who worked in Slavonic Wagria near Plön Lake (the region of present-day Lübeck) in the second half of the twelfth century, relates in his Chronica Slavorum that the prophecies of Svantovit's oracle were greatly trusted and for that reason gifts

90-91

![]()

were sent to him from all Slav lands, even from the non-Slavonic neighbours, as proved by a precious cup, the gift of the Danish King Sweyn. Every year human sacrifices were made to Svantovit's idol from among the Christian prisoners. The inhabitants of Rügen had a reputation as being the most obdurate pagans, and of all the Slavs they held out the longest against the adoption of Christianity.

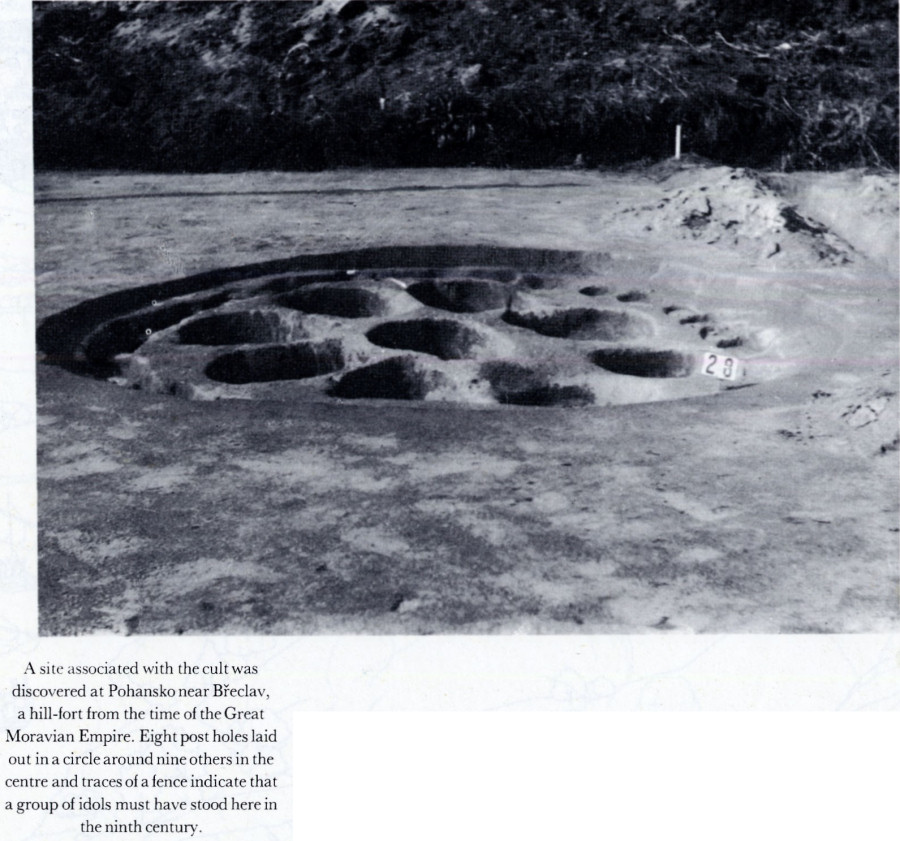

A site associated with the cult was discovered at Pohansko near Břeclav, a hill-fort from the time of the Great Moravian Empire. Eight post holes laid out in a circle around nine others in the centre and traces of a fence indicate that a group of idols must have stood here in the ninth century.

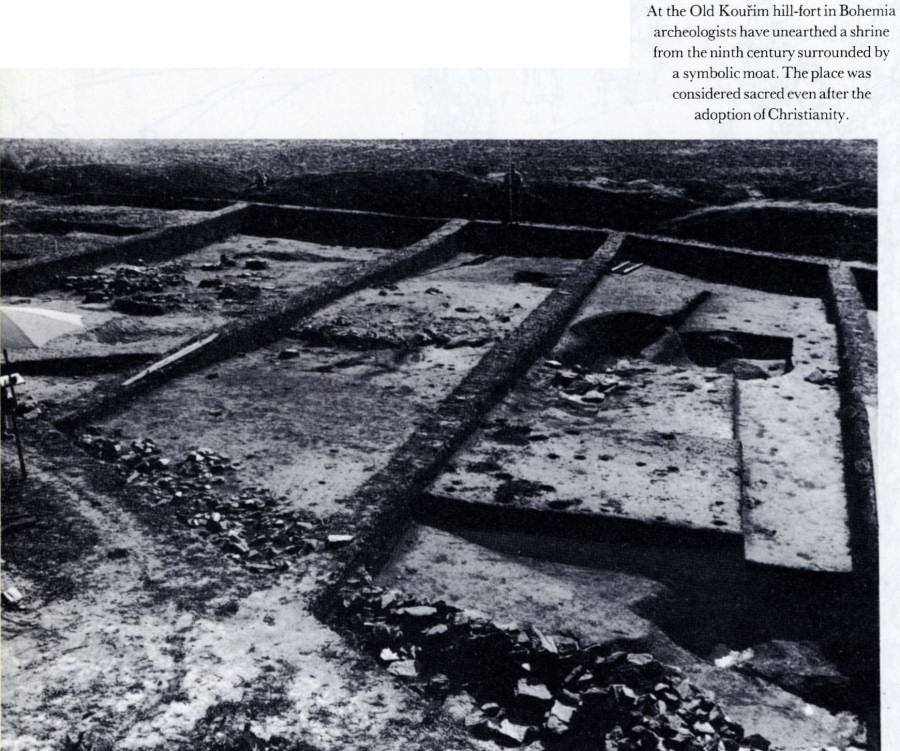

At the Old Kouřim hill-fort in Bohemia archeologists have unearthed a shrine from the ninth century surrounded by a symbolic moat. The place was considered sacred even after the adoption of Christianity.

Similar evidence about the cult of Svantovit and its disappearance was recorded by the Danish priest Saxo Grammaticus, who died at the beginning of the thirteenth century. He gave a vivid description of the temple built on a mound in the centre of the fortified town of Arkona in the most northerly corner of the island. The temple was surrounded by a wall, adorned with carefully executed carvings and crudely painted motifs. Only one gate led into the shrine itself. The temple proper had an outer wooden wall, supporting a red roof, and inner walls of magnificent rugs, hung on four pillars. Inside stood the wooden idol, larger than life-size, with four heads, two of which were turned to the front and two to the back. In his right hand he held a metal horn, which the priest in attendance filled with wine every year and from its level estimated the harvest in the coming year. By the side of the idol lay a bridle, saddle and numerous insignia, among which greatest admiration was roused by a gigantic sword with a beautiful hammered silver handle and sheath. Furthermore a white horse was consecrated to Svantovit, on which only the priest was allowed to ride. They believed that Svantovit used it to go out fighting at night, because in the morning the horse was found sweating and muddy, as if it had returned from a long journey. With the aid of the horse they foretold the success or failure of military expeditions being planned: if the horse stepped over a number of lances placed in front of the temple right leg first, it was a favourable sign; in the opposite case, they would abandon such an expedition. Only one priest was permitted to enter the temple and did so holding his breath — each time he needed to breathe he had to run back to the door. Sacrifices were made in the form of wine and a large round honey bun. The ceremony was followed by a lively banquet at which none was allowed to remain sober. Svantovit's sanctuary was guarded by a company of three hundred riders, who also saw to the enlargement of the temple treasure. With his attributes Svantovit most closely resembled the Roman god of war Mars, even though, as the ceremony with the horn shows, he also had other functions.

Since the location of Arkona is well known — remains of its mighty ramparts to this day stand up to the waves of the Baltic Sea on the chalk cliffs of Arkona Point — it is not surprising that it attracted the interest of archeologists. This culminated in 1921 in excavations by one of the leading German archeologists Carl Schuchhardt. Following Saxo's descriptions he concentrated on a slightly raised plateau in what he assumed to have been the centre of the town, now largely swallowed up by the sea. Schuchhardt managed to find the foundations of a square structure with four posts inside and marks of the stone base of the idol. Without hesitation he declared this to be the temple he had been looking for. The scientific world on the whole accepted his interpretation, though doubts began to arise after the Second World War, by which time techniques of research and documentation had greatly improved.

92

![]()

The map shows the sites of the most important archeological finds of Slavonic pagan shrines and idols.

A clay disc with an incised symbol of the sun was connected with a certain cult or magical practices (Libušin, Bohemia, sixth to seventh century).

According to today's standards of archeology Carl Schuchhardt did not carry out his excavations in too exact a manner — he cut only narrow trenches instead of opening up a larger area, which would have given an overall picture of the site. Divergencies from the description provided by Saxo Grammaticus, both in size and the technique of building, led the Danish archeologist E. Dyggve to the conclusion that the object discovered by Schuchhardt might at best have been the remnant of a Danish mission church built on the site of pagan sanctuary, as was the customary practice of the Church. The final development in this dispute was

93

![]()

reached when H. Berlekamp carried out new excavations in the place where Schuchhardt had dug and found nothing but the remnants of internal fortifications. The shrine itself must have stood further to the east, where today everything is beneath the waves of the Baltic Sea. We shall never know its precise location and must rest content with the description given by the Danish chronicler.

This wooden idol found at Altfriesack (GDR) is probably related to a fertility cult. Radiocarbon tests have dated it to the second half of the sixth century, i.e. the beginning of Slav settlement.

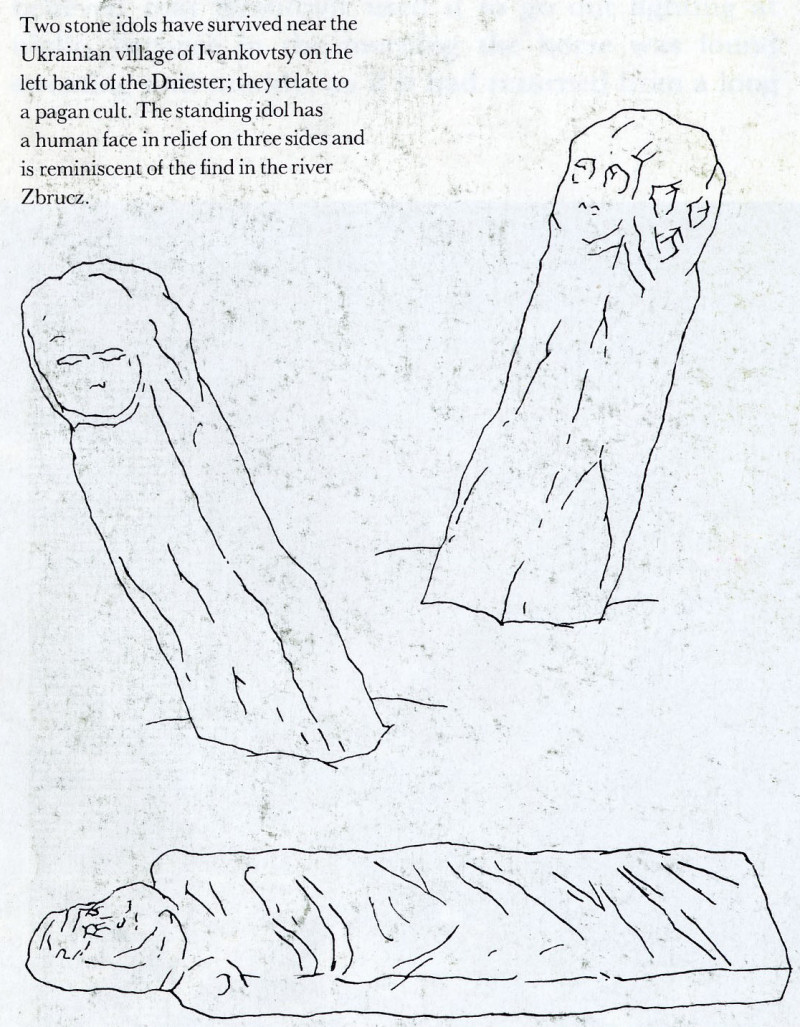

Two stone idols have survived near the Ukrainian village of Ivankovtsy on the left bank of the Dniester; they relate to a pagan cult. The standing idol has a human face in relief on three sides and is reminiscent of the find in the river Zbrucz.

This wooden figure attached to the wall of a building at the hill-fort at Behren-Lübchin (GDR, eleventh to twelfth century) is also connected with the cult.

Schuchhardt's assumed discovery of the second most important temple of the Baltic Slavs — Rethra — met a similar fate. This main temple of the Retharii tribe was first described by Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg, who died in 1018. He related that in the centre of a sacred grove there stood a magnificently decorated temple made of timber, built upon animal horns; it contained a number of idols fully dressed in armour. The most important among them was dedicated to Svarozhich, who was thought to be the son of the sun-god Svarog, known too as a member of the pantheon of the Eastern Slavs. He was worshipped together with Svantovit by all the Slavs in the north, and human sacrifices were made to him, e.g. in 1066 Bishop Johann of Marienburg. A sacred horse was consecrated to Svarozhich and was used by the priests in their prophecies. The temple was finally pulled down in 1068 and Bishop Burchard rode back to Halberstadt on this horse to humiliate the pagans.

Thietmar relates somewhat obscurely that the town of Rethra was triangular (tricornis) and had three gates. In view of the large number of similarly built castles surviving in the north, the archeologists looked for Rethra in at least twenty places. Generally they accepted the view put forward by Carl Schuchhardt, who in 1922 undertook a minor excavation on the fortified Schlossberg near Feldberg on the shores of Lake Feldberg. He declared this to be the site of the Rethra that they had been looking for and explained its "three-cornered" appearance by the fact that there were three gates with towers.

The imposing location of Schlossberg in a dense beech-wood makes this hypothesis highly plausible and attracted modern archeologists who sought to put it to

94

![]()

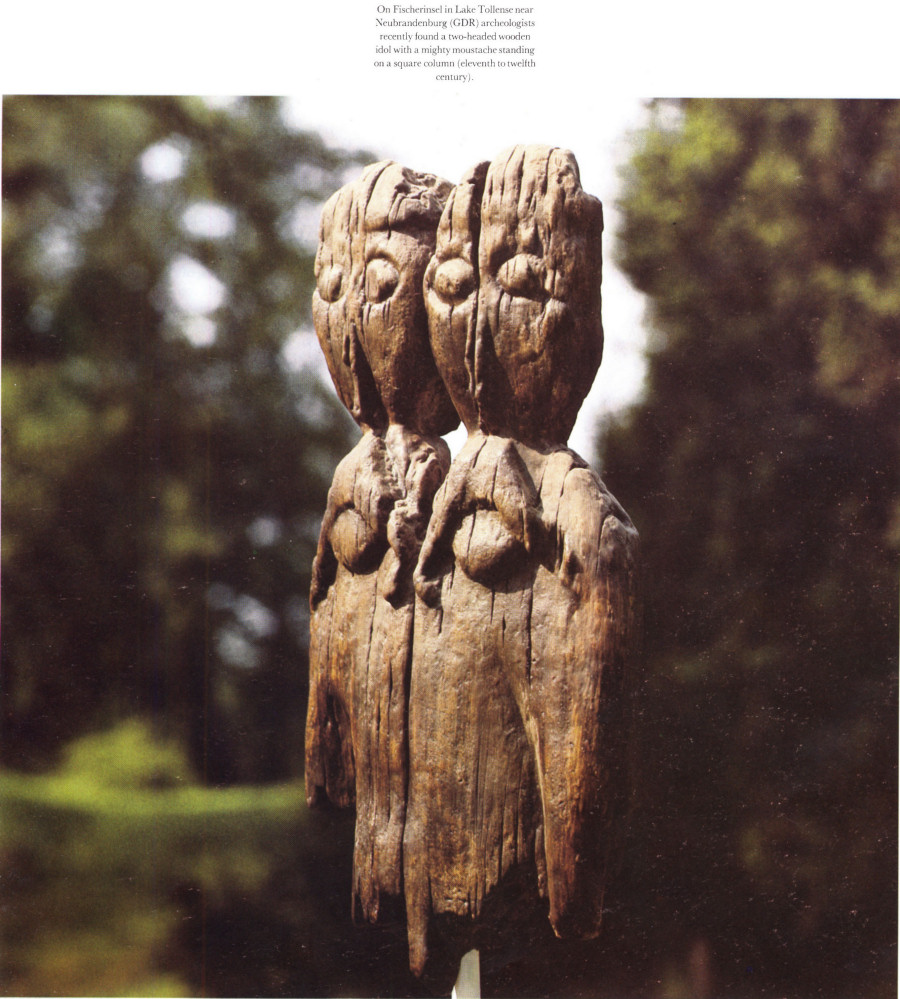

On Fischerinsel in Lake Tollense near Neubrandenburg (GDR) archeologists recently found a two-headed wooden idol with a mighty moustache standing on a square column (eleventh to twelfth century

the test. Excavations by J. Herrmann in 1967 indeed confirmed that this had been an important tribal centre, in which, to judge by the density of dwellings, some six to twelve hundred inhabitants had lived permanently. He even discovered the temple, but not at the top of the hill-fort, as Schuchhardt had assumed, but on a spur projecting above the lake, on a site surrounded by a moat. But his finds showed clearly that the hill-fort at Feldberg had been used in the seventh to ninth centuries, while there was not a trace of settlement at the time when Rethra enjoyed its greatest fame as historically recorded, i.e. in the tenth

95

![]()

and eleventh centuries. This case, too, still remains open — at least for the time being — and the search needs to be continued. Thietmar's description does not fit the Feldberg temple, which was a simple rectangular building divided into several parts and separated from the hill-fort itself by a moat.

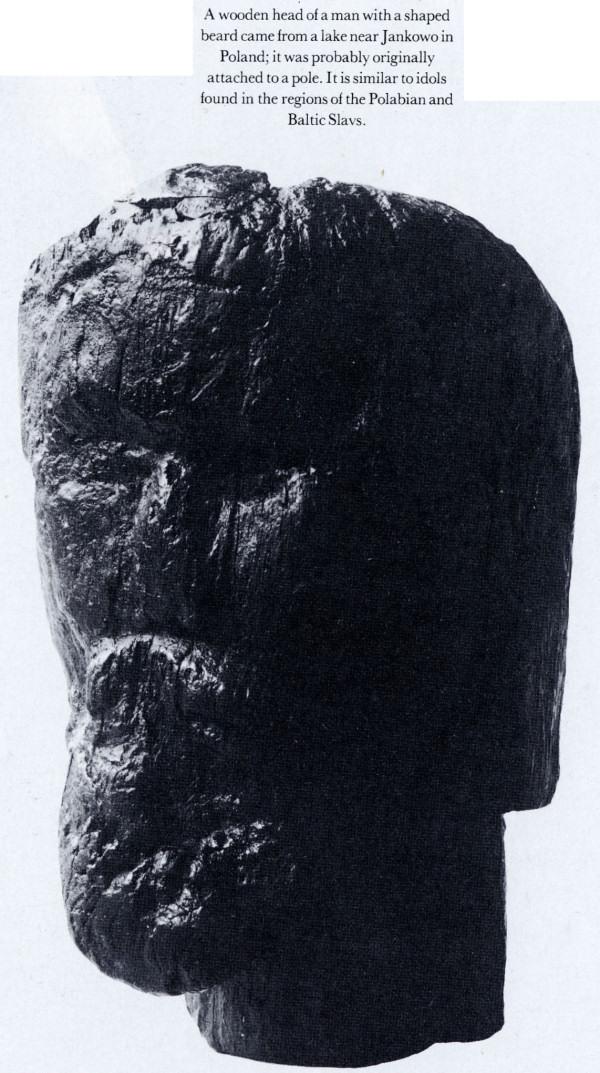

A wooden head of a man with a shaped beard came from a lake near Jankowo in Poland; it was probably originally attached to a pole. It is similar to idols found in the regions of the Polabian and Baltic Slavs.

Archeologists have managed to form some impression of the anonymous cult places consecrated to local gods, which are known to have existed in large numbers. In western Pomerania two such places were discovered at Trzebiatów (Gryfice district) in 1931—3. There were two moats of oval ground plan, 65 m or 70 yds apart, whose shallow depth (0.5—1 m or about 2.5 ft) and width (1—1.5 m or about 4 ft) provided no more than symbolic protection. In the midst of the smaller oval (8 x 10 m or 26 x 33 ft) traces were found of a single fire that must have burnt there. Inside the larger oval (10 x 13 m or 33 x 43 ft) there were two hearths and three wooden idols, of which only three post holes survive. Sacrificial fires burnt likewise in the moats, to judge by charcoal found there. These two cult places were related to a settlement dated by finds into the ninth to tenth centuries.

Soviet archeologists discovered a similar cult place belonging to the Eastern Slavs at Peryn' near Novgorod. The Novgorod Chronicles reveal that the local Slavs resolutely refused to adopt Christianity and were forced to submit to baptism only after heavy battles. Akim, the first Patriarch of Novgorod, had the Perun idol cast into the river Volkhov. This idol had been set up in the tenth century by Dobrynya, uncle of Vladimir, the first Christian ruler of Russia. An old tradition relates that this place was in the village of Peryn', lying near Novgorod at the point where the Volkhov flows out of Lake Il'men'. While philologists regarded the derivation of Peryn' from Perun with reservations, the Moscow archeologist V. V. Sedov managed to uncover remnants of a pagan temple in the premises of Peryn' Monastery (1948, 1951—2). It had a circular ditch with eight shallow niches, in which ceremonial fires burnt. In the centre of the circle stood the idol, of which only the pit is left today. Traces of other similar circles, clearly to be associated with idols of minor gods, were later discovered along the sides.

Written records exist which show that temples were built similarly in Bohemia: shrines were set up and

96

![]()

idols of gods and the figures of ancestors dědci were worshipped. The first Slav settlers of the country brought these with them if we are to believe the legends about Old Father Czech. St Vitus's Cathedral at Prague Castle, for instance, was built on the site of an ancient pagan shrine called Žiži. The name suggests ceremonial fires that burnt here in honour of we do not know what gods. Some shrines can be recognized by the big piles of bones of sacrificial animals, mostly in the vicinity of burial grounds, the remnants of funeral feasts, a custom that was widespread among the Slavs. This was the case at the former Church of Our Lady at Prague Castle, where entire young wild boars were found. Similarly in Loretto Square (Loretánské náměstí) near Prague Castle there was a pit with six skulls of cattle and a large number of animal bones next to a shrine surrounded by stones. Traces of other shrines were discovered near ninth- and tenth-century burial grounds.

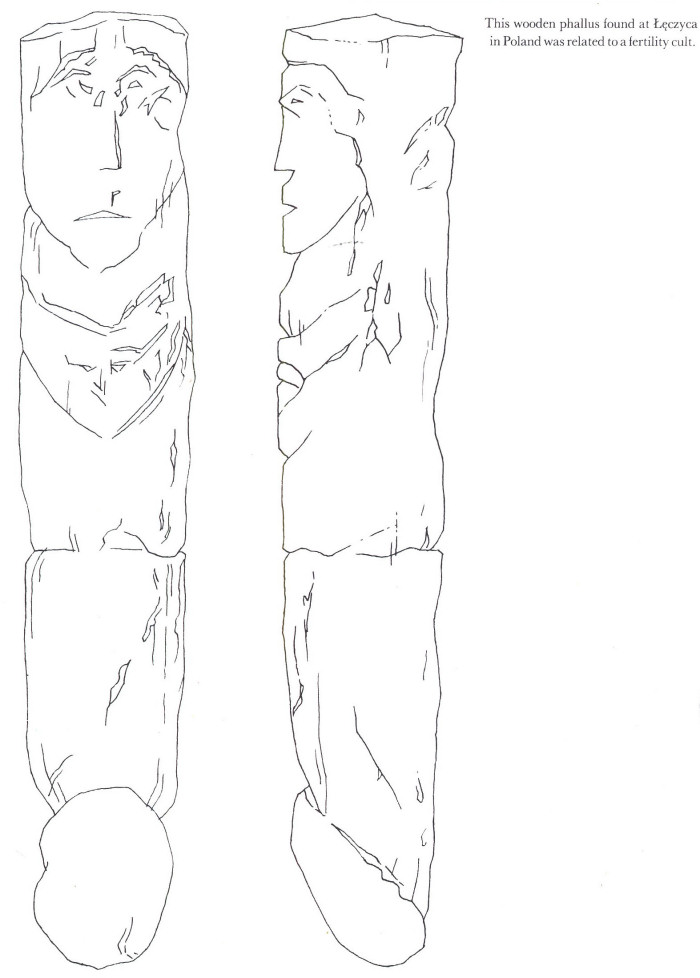

This wooden phallus found at Łęczyca in Poland was related to a fertility cult.

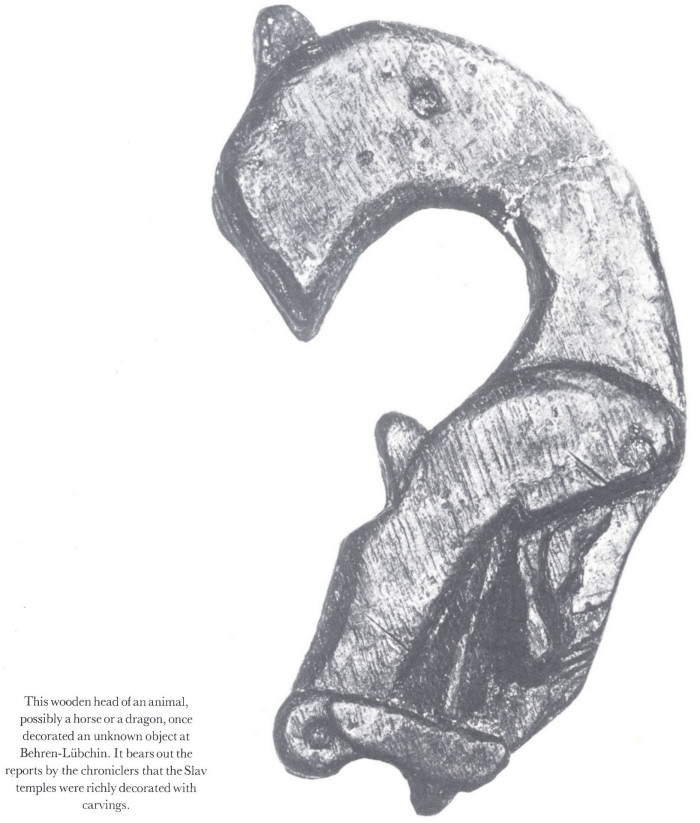

This wooden head of an animal, possibly a horse or a dragon, once decorated an unknown object at Behren-Lübchin. It bears out the reports by the chroniclers that the Slav temples were richly decorated with carvings.

A typical example is the enclosed sacred precinct near the prince's burial ground at the hill-fort in Kouřim, in the ninth and early tenth centuries the centre of the Zličané tribe. It included a little lake called Libušinka, with a spring filled by rainwater running down the underlying rocks into a ravine between the inner and outer earthworks of the hill-fort. The inhabitants dug a pond 40 x 70 m (130 x 230 ft) in size, its walls strengthened with wooden posts and laid out good access to the water. The importance of the shrine is shown by the fact that it was symbolically

97

![]()

surrounded by a ditch, which enclosed the area on the north-western banks of the little lake. Ceremonial fires in honour of the god of the spring burnt in a number of pits in the ground between it and the lake. The level of the lake might well have served as an oracle, as was the case, for example, among the Polabian Slavs. It is interesting that this place retained its function as a sacred precinct even after the adoption of Christianity. The little lake, its fence fortified with a stone wall, served as a natural font for baptism, in which adults were christened by submersion. On its banks, on the south-western end of the burial ground, stood a small wooden Christian chapel.

A lead amulet in the shape of a fish, which was to ensure the person who wore it a rich catch (Neubrandenburg, Fischerinsel, eleventh century).

Mountains were also held to be sacred. In Bohemia this must have applied to Mount Rip, worshipped for its striking shape and location in the Central Bohemian Plain even before the arrival of the Czech Slavs. According to legend, their ancestor, Old Father Czech, stood on the mount and decided there and then that his people should settle in this land. There are archeological finds to prove that other hills were likewise worshipped: for instance on the summit of Milešovka, the highest mountain in the Central Bohemian Massif, ninth-century sherds have been found, which cannot have come from any settlement, and, furthermore, a little disk of horn with the symbol of the sun incised upon it.

Convincing archeological proofs of Slavonic paganism are finds of idols in wood, stone and metal. Wooden gods survived only in favourable soil conditions as, for instance, in the region of the Polabian and Baltic Slavs. Among older finds there is, first of all, an idol that came from the southern shores of Lake Ruppin, close to the Slav hill-fort of Altfriesack. To begin with it was not certain whether the idol was of Slav origin, but archeologists turned to the physicists for help. Using radio-carbon tests (1967) they dated the statue to the second half of the sixth century, i.e. the very beginning of the Slavic settlement in those parts. One cannot help thinking of the old Czech legends written down by Chronicler Cosmas, where he speaks of the gods that the forefathers of the Czechs brought along on their

98

![]()

shoulders when they came to settle in the land. The idol of Altfriesack is carved in oak and represents a slim male figure with an opening for the phallus, which was separately attached, clearly as a symbol of the god of fertility. Similar idols have been found near the hill-fort at Behren-Lübchin and at Braak (Eutin district). The phallic cult of fertility, which is mentioned in written records, e.g. among the Eastern Slavs, was confirmed by the discovery of an oaken phallus at Łęczyca near Łódź in Poland.

The little head of a man from Merseburg (GDR) carved in horn must likewise have depicted some unknown god.

Idols were also made of other materials. There is, for instance, a Svantovit stone walled into the church at Altenkirchen near Arkona, depicting in relief a male figure holding a mighty drinking horn — the symbol of Svantovit. A similar stone — likewise set into a church wall — can be found at Bergen on the island of Rügen.

The Gerovit (Jarovit) stone with a primitive picture of the local god holding a cudgel in his hand as a symbol of his function as a god of war exists at Wolgast.

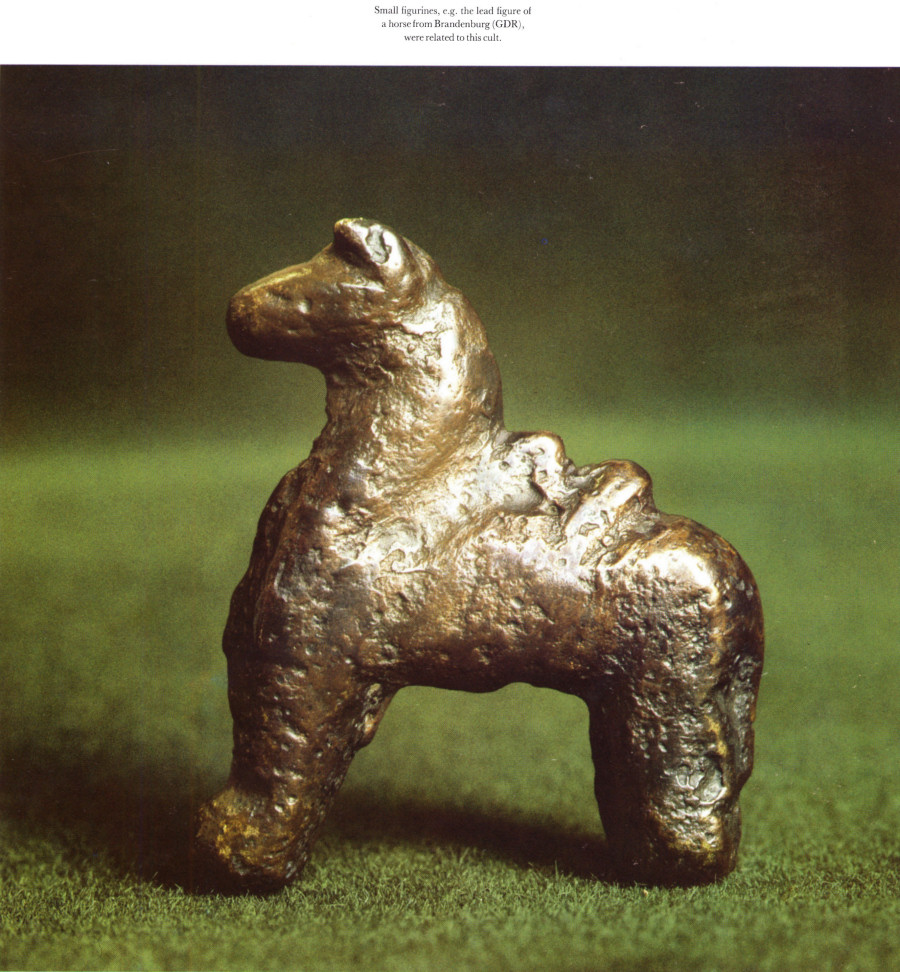

Apart from these large figures smaller statues likewise related to the cult, for example a lead figurine found in a grave near Weggun (Prenzlau district), a bronze figure of a man in the hill-fort at Schwedt in the Oder region, a little head of bone at Merseburg, etc. There were also cult animals e.g. lead fish amulets at Wustrow on Lake Tollense and at Fergitz near Prenzlau, also a serpent carved from a stag horn, found at Gorke near Anklam, and particularly figures of horses The little head of a man from — the attributes of gods of war such as the little lead Merseburg (GDR) carved in horn must horse unearthed at Brandenburg.

A recent find of two oak idols in a fortified settlement on the Fischerinsel in Lake Tollense south of Neubrandenburg

99

![]()

caused great excitement. The settlement dates from the eleventh to the twelfth century. One of the idols, 165 cm (65 in) tall, represents a female goddess; the head is roughly hewn, and stress is placed on the features showing her sex. It is interesting that it was carved to be seen at a slanting angle from the front so that it must have stood as a secondary goddess in the corner of the temple. The other idol depicts a two- headed male god, 170 cm (67 in) tall, standing on a square post. Both his heads sit on one shoulder and the most characteristic features are mighty drooping moustaches.

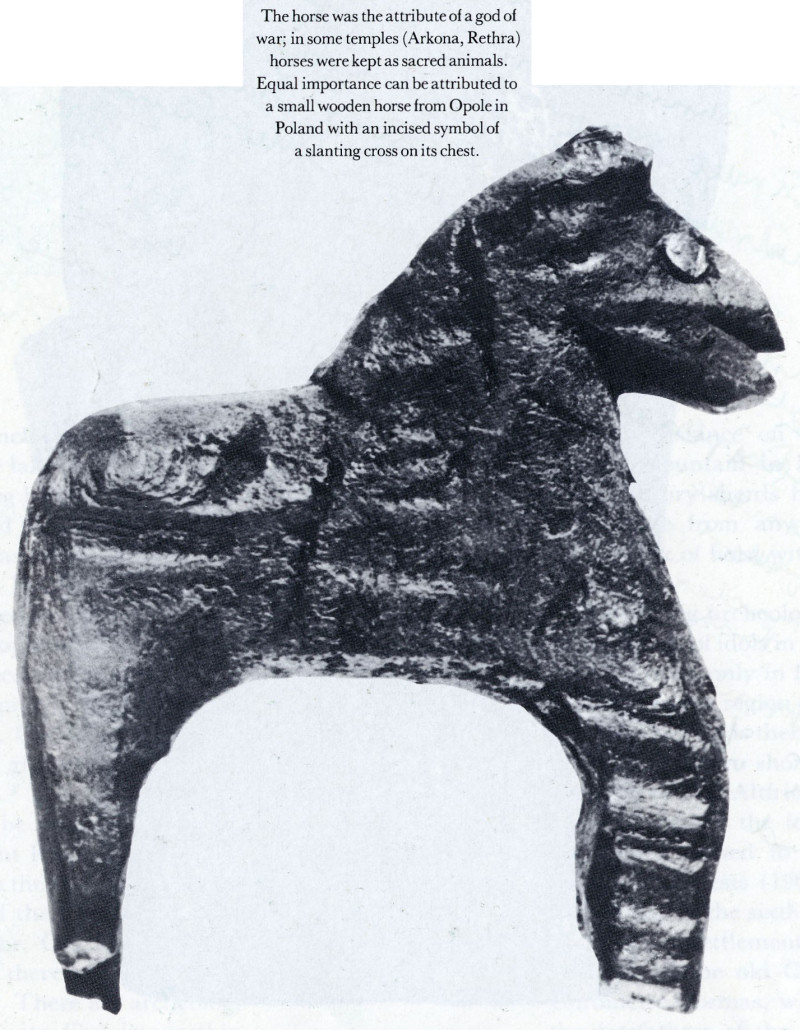

The horse was the attribute of a god of war; in some temples (Arkona, Rethra) horses were kept as sacred animals. Equal importance can be attributed to a small wooden horse from Opole in Poland with an incised symbol of a slanting cross on its chest.

The extinction of the original religion of the Slavs was caused primarily by an internal crisis due to social changes. To them the culturally more advanced Christian civilization, which introduced the feudal system of society, better corresponded. This transition did not take place without resistance. In the Czech lands, for instance, there was a pagan uprising by Strojmir against the first Christian prince, Bořivoj, in the last quarter of the ninth century, and in the eleventh century it was still necessary for decrees to be published against pagan customs. In Bulgaria, too, there was a pagan reaction under Boris's heir Vladimir. Instead of him Boris gave the throne to his younger son Symeon, who completed Boris's work of Christianization.

This process progressed slowly among the Eastern Slavs, where pagans were still living in the remote areas of medieval Russia during the fifteenth century. Very great resistance was also put up by the Polabian and Baltic tribes.

It is clear that the presence of determined pagans in the heart of Europe was considered an anomaly in Western Christendom in the eleventh and twelfth centuries to be eliminated as soon as possible. Hence the persistent efforts over the centuries to use force to cast out this scandalous religion. In the year 1147 a major crusade was undertaken against the Obodrites and Liutizi instead of to the Holy Land following an appeal issued by St Bernard of Clairvaux. Under the leadership of Henry the Lion, Albert the Bear, the archbishops of Magdeburg and Bremen, the papal legate Anselm and other famous princes, it was composed of the armies of Saxony, Denmark (including its fleet), Bohemia and Poland. The undertaking was not very successful from a military point of view, but by laying the country waste and decimating the population it broke the strength of the Baltic tribes to such an extent that within a few decades they succumbed completely. Their pagan ideology in its decadent and atavistic form could not stand up to the more advanced Christian civilization.

100

![]()

Small figurines, e.g. the lead figure of a horse from Brandenburg (GDR), were related to this cult.

101

![]()

The year 1168 brought catastrophe to Slavonic paganism on the Baltic Sea. Its last bastion - the famous Svantovit temple at Arkona on the island of Rügen — was destroyed by King Waldemar of Denmark.

102-103

![]()